11.2: The Movement Expands

- Page ID

- 127022

The Chicano, American Indian, Asian, Feminist, and Gay Pride movements, although rooted in long-standing concerns and grievances, were influenced and informed by the decade’s earlier struggles. Civil rights and farm worker advocates, emphasizing political, economic, and social justice, inspired other groups to seek the same opportunities. Similarly, the Black Power movement’s call for cultural pride and self-determination resonated with other disfranchised minorities and subcultures.

The Chicano Movement

By 1960, California’s Mexican American population was primarily urban. The majority lived in barrios, characterized by underfunded schools, high levels of unemployment, deteriorating housing, and inferior public services. Like black ghettos, barrios were also plagued by police brutality, spatial isolation from more affluent areas, and poorly planned “redevelopment” schemes that destroyed affordable housing and displaced stable neighborhood businesses. Population concentration, however, brought the possibility of greater political power. The Mexican American Political Association (MAPA), recognizing this potential, sought to build on the modest political gains achieved by postwar activists. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, the cornerstone of Johnson’s War on Poverty, also bolstered the optimism of urban Mexican Americans by promising funds to attack barrio poverty.

Optimism soon turned to disillusionment. In 1962, MAPA helped elect John Moreno and Philip Soto to the state assembly, but both lost in the next election after their political opponents succeeded in reapportioning their districts. During the same period, Los Angeles City Councilman Edward Roybal was elected to Congress, but this major victory left the city’s Mexican Americans without representation in city government. The council, instead of calling for an election, appointed Gilbert Lindsay, an African American, to Roybal’s seat. Even the state’s liberal governor, Pat Brown, seemed to ignore the barrio electorate, appointing fewer than 30 Mexican Americans out of a total of 5000 possible appointments. Finally, the War on Poverty, while raising expectations among Mexican Americans, directed a disproportionate amount of funding to programs in black communities.

These developments, occurring at a time when African Americans were embracing Black Power and the UFW was forcing concessions from growers, inspired young urban Mexican American activists to adopt more militant strategies for social and political change. Rather than emphasizing assimilation into Anglo culture, the Mexican American youth demanded their “right as a people to have their own culture, their own language, their own heritage, and their own way of life.” Like Black Power advocates, they argued that self-determination, cultural pride, community self-defense, and Third World solidarity were the true sources of liberation. And like black activists, they believed that recovering their history—a history that had been “distorted” by whites in order to justify exploitation and discrimination—was a crucial first step in forging a new movement.

Their narrative history, which ran counter to most standard textbook accounts, asserted that the Southwest was theirs. The region, they argued, was the original homeland of their indigenous ancestors. After the Spanish conquest,their forebears (now of mixed European and Indian ancestry) created avast New World empire that extended into the Southwest, an empire inherited by the Mexican Republic following the war for independence. In the late 1840s, Anglos, determined to extend their own empire, then seized Mexican territory in an unprovoked and unjustified war, stripped established residents of their land, and transformed a once proud people into a poorly paid, menial labor force. To a new generation of Mexican American activists who called themselves “Chicanos,” this historical equation led to one conclusion: California belonged to La Raza—the Mexican Americans. Changing demographics added symbolic weight to their assertion. Between 1960 and 1970, for example, the Hispanic population in Los Angeles County grew from 576,716 to 1,228,295. This increase, not reflecting large numbers of undocumented immigrants ignored by the census, stood in contrast to a two percent decline in the Anglo population. While still in the minority in the county as a whole, the Mexican American population constituted a strong majority within certain communities and districts.

The Mexican American claim to power, based on these shifting demographics and a new sense of cultural pride, took several different forms. In the political arena, some activists abandoned their struggle for recognition and representation within the two parties and established organizations devoted to their empowerment. The La Raza Unida Party (RUP), founded in the late 1960s, enjoyed its greatest success in 1970 and 1972, when it inspiredMexican Americans throughout the Southwest by wresting political control from an Anglo minority in the Crystal City area of Texas. In California, however, the party’s political influence was less direct. In 1971, for example, the RUP registered enough voters to dilute the strength of the Democratic Party and cost it the election in the 48th assembly district. The RUP’s candidate, Raul Ruiz, a college professor and editor of La Raza magazine, took just enough votes away from Democrat Richard Allatorre to hand the election to a non-Hispanic Republican. This prompted state Democrats, who had long taken the Mexican American vote for granted, to run more Hispanic candidates in future elections. Despite small advances of this nature, however, the potential political power of Mexican Americans continued to be undermined by language barriers, gerrymandering of political districts, the constant influx of new immigrants, and the low level of voter participation by established residents.

Mexican American activists also sought reform in the educational arena. In March of 1968, thousands of students walked out of their high schools in the Los Angeles area, protesting racial bias among Anglo teachers, the lack of Hispanic administrators and instructors, dilapidated school infrastructure, an uninspiring curriculum that ignored Mexican American culture and history, and the tracking of students into vocational classes. Their action inspired similar protests in high schools across the nation. Similarly, on the state’s college campuses, students formed organizations like United Mexican American Students (UMAS) and El Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan (MECHA) to press for Chicano or Mexican American studies programs, more financial aid and student services, and the hiring of Mexican American faculty. Their efforts, often supported by students of other ethnicities, led to the establishment of more than 50 Chicano studies programs in state colleges and universities across the nation by 1969. Finally, activists launched a long struggle for bilingual education programs in elementary and secondary schools, winning a legislative mandate in 1976.

Heightened appreciation of Mexican American history and culture extended beyond high school and college campuses into the barrios. Activists established cultural centers, organized mural projects, formed theater and dance troupes, and published magazines and journals like La Raza, Inside Eastside, and El Grito: A Journal of Contemporary Mexican American Thought. Barrio youths, influenced by this cultural renaissance, attacked community problems with a heightened militancy and sense of purpose. The Brown Berets, which grew out of an East Los Angeles youth group called Young Citizens for Community Action, emphasized cultural nationalism, self-determination, and community self-defense. Like the Black Panther Party, the Berets organized citizen patrols to monitor police activity within their communities. And like the Panthers, they soon became targets of law enforcement infiltration, harassment, and intimidation.

Police antagonism toward the Brown Berets and the barrio-based Chicano movement took an ugly turn in the fall of 1970. In 1969, the Berets helpedform the National Chicano Moratorium Committee, an organization opposed to the U.S. war in Vietnam and to discriminatory selective service policies. Mexican American youths, less likely to attend college than Anglos, received fewer student deferments. They also lacked the political connections that allowed some of their white counterparts to escape the draft or receive assignment to less risky branches of the military. As a consequence, they were drafted in disproportionate numbers and suffered a disproportionate level of casualties in fighting what many of them regarded as an unjust war against other people of color. On August 29, 1970, the Moratorium Committee sponsored a march and rally in East Los Angeles. Following the march, 20,000–30,000 participants, including families with small children, gathered peacefully in Laguna Park to listen to music and speakers. Police, in an unprovoked show of force, moved in and disbanded the demonstrators with clubs and tear gas. In the process, hundreds of citizens were arrested, 60 injured, and two killed.

In the late afternoon, after most of the demonstrators had dispersed, Ruben Salazar and two of his coworkers who had been covering the day’s events for a Spanish-language television station took a break for a beer in the Silver Dollar Bar. Police, claiming to have seen a man enter with a rifle, surrounded the bar, fired in tear gas canisters, and prevented patrons from leaving. One of the canisters hit Salazar in the head, killing him. His death was not an unfortunate accident or product of police overreaction, charged the Mexican American community. Salazar had earlier exposed Los Angeles Police Department brutality in a case of mistaken identity that led to the shooting deaths of two Mexican nationals. The police had warned Salazar that he would pay the consequences if he did not tone down his coverage. Despite serious evidence of misconduct, no officers were charged for Salazar’s death, and police– community relations remained deeply troubled.

Although police brutality, lack of political representation, and poverty continued to plague California’s barrios, the Brown Power movement helped

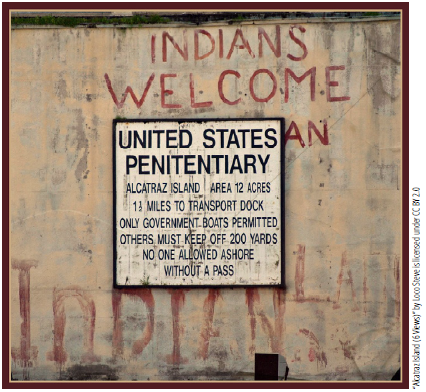

In this photograph young Indian activists used graffiti to assert their claim to physical space, Alcatraz Island. Does the image suggest that they were also asserting a new cultural political identity?

promote a more positive sense of identity among urban Mexican Americans. Moreover, it had a lasting impact on higher education. During the 1970s and 1980s, state colleges and universities attracted increasing numbers of Mexican American students through affirmative action, financial aid, and ethnic studies programs. This, combined with a greater commitment to affirmative hiring policies in the public and private sectors, led to the growth of the Mexican American middle class, increased representation in professional occupations, and a new, better-educated generation of political leaders.

Taking the Rock

In the late 1960s, the state’s American Indian population responded to the pressures and challenges of termination, relocation, poverty, and broken treaties with an assertion of “Red Power,” a movement that emphasized culturalpride, intertribal unity, and mutual aid. Indians created the foundation for this movement throughout the 1950s and 1960s by building a new institutional power base. The Intertribal Friendship House in Oakland, the San Francisco Indian Center in San Francisco, the United Bay Area Council of American Indians, and the Intertribal Council of California united “relocates” who came from tribes across the nation with California Indians and provided them with a forum for articulating shared concerns. Other organizations, devoted to cultural preservation and education, also took root. In 1964, the chairman of the Cahuilla tribe organized the American Indian Historical Society to promote scholarship on Indian life, culture, and history, and the revision of school textbooks. In 1967, the California Indian Education Association was founded to promote Native American studies programs on college campuses and to encourage political activism among the Indian youth.

At the same time, Indian youths were influenced by the Black Power and Chicano Power movements. Impatient with the pace of change, they adopted more militant forms of struggle for cultural recognition and redress. Their protests paid off. By 1969, several college campuses had established Native American studies programs or study groups. In November of 1969, student activists, with the support of Indian organizations and their leadership, planned and carried out the occupation of Alcatraz Island. Launched after a fire destroyed the San Francisco Indian Center—a central gathering place of Bay Area Indians—this action signaled the birth of the Red Power movement. Led by Richard Oakes, a Mohawk Indian and Bay Area student, the “invaders” adopted the name “Indians of All Tribes” to underscore their diverse backgrounds. Other veterans of the occupation included Adam Fortunate Eagle (Anishinabe-Ojibway), John Trudell (Sentee-Sioux), La Nada Boyer (Shoshone-Bannock), Edward Castillo (Cahuilla-Luiseño), Millie Ketcheshawno (Mvskoke), Shirley Guevara (Mono), Luwana Quitiquit (Pomo-Modoc), John Whitefox (Choctaw), and Wilma Mankiller (Cherokee).

On November 9, 1969, Richard Oakes and several other Indians staged a preliminary and short-lived invasion that convinced them that a longer occupation was viable. Just 11 days later, on November 20, approximately 100 Indians, mostly students, seized the island and issued a series of demands that included permanent title to Alcatraz, and the right to establish a Center for Native American Studies, a Spiritual Center, and an Ecology Center on its soil. They also established an elected council to coordinate day-to-day negotiations with government officials and media relations.

As the months passed, occupiers confronted a series of setbacks. The federal government steadfastly refused to concede to their demands. Hundreds of newcomers, including many non-Indians, arrived on the island, placing stress on existing supplies and services. Competing political factions challenged the original elected council. Oakes, distraught over growing political divisions and the accidental death of his daughter in January of 1970, left the island. In the meantime, the government shut off the island’s electricity and blocked the transport of water from the mainland. A fire broke out three days after the disruption in water supply, destroying several buildings. Finally, on June 10, 1971, federal marshals and FBI agents invaded the island and removed the remaining occupiers.

The Alcatraz activists, however, left a lasting legacy. In the words of La Nada Boyer, an occupation leader, “Alcatraz was symbolic in the rebirth of Indian people to be recognized as a people, as human beings, whereas before, we were not. We were not recognized, we were not legitimate … but we were able to raise, not only the consciousness of other American people, but our own people as well, to reestablish our identity as Indian people, as a culture, as political entities.” Even before the occupation ended, President Nixon formally halted the federal policy of termination and restored millions of acres of land to several tribes. He also increased federal spending on Indian education, housing, health care, legal services, and economic development. The occupation inspired Indians across the nation to engage in similar actions, including the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C., which forced the agency to hire more Indian employees to administer its programs. Another occupation, of a former army base near Davis, California, led to the establishment of D-Q University, the “first and only indigenous controlled institution of higher learning located outside of a reservation.”

Change and Activism Along the Pacific Rim

The 1960s brought massive changes to California’s Asian American communities.

The 1965 Immigration Act, reflecting the more liberal racial attitudes of the postwar, civil rights era, created a new major wave of Asian immigration by abolishing race-based quotas and permitting 170,000 immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere to enter the United States each year. Spouses, minor children, and parents of U.S. citizens were not counted as part of the quota. Prior to the Immigration Act, Japanese Americans constituted the largest percentage of the Asian American population, followed by Chinese, Filipinos, and Koreans. After 1965, however, Japanese Americans dropped from first place, as immigrants from other groups entered the state in larger numbers.

The Chinese population underwent the greatest transformation. Prior to 1965, a majority of Chinese residents were American-born. With the new immigration, however, the number of foreign-born increased to 63 percent ofthe total population. About half of the newcomers, lacking professional or technical training, clustered in existing Chinatowns and worked in low-wage menial or service occupations. This population of “Downtown” Chinese stood in contrast to a second group of immigrants: the “Uptown” Chinese, educated professionals and entrepreneurs mostly from Hong Kong and Taiwan. This group either settled outside of existing Chinatowns altogether, following a pattern adopted by American-born Chinese residents, or established new, upscale suburban enclaves. For example, Monterey Park, which was 85 percent white in 1960, was more than 50 percent Chinese two decades later and was known as the “Chinese Beverly Hills.”

Filipinos, arriving in even greater numbers, were more widely dispersed and homogeneous in education and training than Chinese immigrants. Most were professional and technical workers fleeing economic hardship and political repression in the Philippines. But although highly skilled, as many as one-half of all newcomers worked in low-wage clerical or manual occupations because American professional associations refused to accept their degrees or grant them licenses to practice. This enormous pool of talent from the Philippines, including doctors, lawyers, dentists, engineers, and professors, was virtually wasted in the United States.

Korean immigrants, although facing greater language barriers thanFilipinos, came with similar credentials. A majority were college-educated, middle-class professionals who also faced institutional obstacles in the United States; however, many arrived with the capital to launch small businesses, which in turn fostered the development of ethnic enclaves. Olympic Boulevard in Los Angeles, for example, quickly emerged as a center of entrepreneurial activity, housing churches, grocery stores, insurance companies, restaurants, beauty shops, nightclubs, and travel agencies by 1975. However successful, these business ventures still represented a step down for trained professionals like Kong Mook Lee, who, unable to practice as a pharmacist, opened a sewing factory in Los Angeles. He, and a majority of other highly trained Korean immigrants, never anticipated that their professional skills would be useless in the United States.

As the immigrant population expanded, increasing the size and diversity of the state’s Asian population, many sons and daughters of established residentsreclaimed their ethnic heritage and launched the Asian American student movement. In the Bay Area, Asian American students joined the 1968 Third World Strike at San Francisco State University, organized by a multiethnic coalition of students and faculty that called for the creation of a Third WorldCollege. This, and a second strike that shut down the Berkeley campus in 1969, resulted in the creation of ethnic studies departments on both campuses and fostered ethnic consciousness among participants. Asian American students, in particular, emerged with a new awareness of their own ethnic heritage, history of oppression, and responsibility to their communities. Vietnam War protests also helped radicalize young Asian Americans. Having experienced anti-Asian prejudice at home, they drew parallels between their own experience and the negative stereotypes used to dehumanize the “enemy.”

These experiences encouraged young activists to return to their own roots and recover their culture and history. Cultural organizations, like the Combined Asian Research Project, encouraged young writers, musicians, and artists to produce works that reflected their ethnic heritage and identity, and to establish an Asian American artistic and literary tradition by locating and documenting the contributions of older generations. Others emphasized political activism within their neighborhoods and communities, focusing on housing conditions, sweatshop labor, and the lack of medical, legal, and social services in Asian enclaves. Groups such as the Asian Law Caucus and Asian Law Alliance, for example, provided low-cost legal advice in the areas of housing, immigration, and employment discrimination. For many, however, San Francisco’s International Hotel provided the call to action. By the late 1960s, the hotel, housing a resident population of older, low-income Filipino and Chinese men, and serving as a home base for activist youth organizations, was threatened with demolition by its owner, Walter Shorenstein. A coalition of tenants, resident activists, and college students persuaded the owner to lease the hotel to the United Filipino Association and formed a collective to renovate the building and provide services to the residents.

The hotel soon became a symbol of Asian American unity, selfdetermination, and ethnic pride; however, financial problems and factional struggles among different activist groups undermined the collective experiment, prompting the owner to proceed with eviction and demolition plans. In August of 1977, after activists had exhausted all legal and political options for saving the hotel, they rallied more than 2000 supporters to surround the building and block the eviction. Police used force to break through the crowd and remove the tenants from the hotel. The building was eventually demolished, but the site remains vacant because of ongoing political pressure from community activists who insist that low-income housing be part of the development agreement. Of less symbolic—but more lasting—significance was the creation of Asian American studies programs on college and university campuses, increased political participation and representation, and an enduring cultural influence in music, literature, art, film, and theater.

Emerging Feminist and Gay Rights Movements

During the ’60s, a relatively quiet but growing movement went largely unnoticed in the face of more dramatic, noisy protests against the status quo. Just as young women were confronting sexism within the decade’s social movements, an older generation of “liberal feminists” began working through legal and political channels to address gender bias in education and employment. In 1964, these mostly white, middle-class professionals convinced the California legislature to establish a State Commission on the Status of Women. Over the next three years, the commission worked to document widespread gender inequities and sent delegates to the National Conferences of the State Commissions on Women. At the third national conference, held in Washington, D.C., in 1966, delegates criticized the federal Economic Opportunity Commission for failing to investigate complaints of sex discrimination. Following the closing luncheon, several participants formed the National Organization for Women (NOW) to “break through the silken curtain of prejudice and discrimination against women.”

California’s liberal feminists returned home determined to organize local and state chapters of NOW. In 1967, the State Commission issued its longawaited report on the status of women, along with a series of proposed legislative remedies. When Governor Reagan ignored its recommendations, liberal feminists were ready to fight back. By the early 1970s, when they were joined in their struggle by younger activists who had encountered sexism among their “radical” male colleagues, a full-fledged feminist rebellion would emerge.

In a similarly quiet manner, gay and lesbian activists worked diligently throughout the ‘60s to promote greater acceptance of homosexuality among California’s heterosexual majority. Their efforts, emphasizing political engagement, public education, and cooperation with sympathetic liberals, grew out of the same desire for inclusion that informed early civil rights struggles. In 1961, for example, a gay San Franciscan formed the League for Civil Education (LCE), which sought to build a political voting block among the city’s homosexual residents. In 1964, the Society for Individual Rights (SIR)—an LCE spin off—was formed to promote electoral unity and activism as well as “a sense of community; and the establishing of an attractive social atmosphere and constructive outlets for members and friends.” By 1967, SIR and the Daughters of Bilitis (1955) began hosting “Candidates Nights,” where those seeking political office could meet their gay and lesbian constituents.

Beyond the political arena, organizations like LCE, SIR, the Mattachine Society (1950), and the Daughters of Bilitis created opportunities for social engagement outside of the more closeted confines of gay and lesbian bars. In 1966, for example, SIR established the nation’s first gay community center on 6th Street in San Francisco. They had also won a small measure of public tolerance by building coalitions with sympathetic heterosexuals. In 1964, gay and lesbian activists joined with liberal San Francisco clergy to form the Council of Religion and the Homosexual (CRH), an organization that promoted acceptance of homosexuality within mainstream religious denominations. On January 1, 1965, the CRH held a fundraising ball. As guests arrived—both gay and straight—they were harassed and photographed by police. Officers also arrested CRH lawyers who had demanded a search warrant when police attempted to enter the hall. For the first time, heterosexuals experienced the officially sanctioned intimidation and brutality that had long been used to break up gay and lesbian social activity in bars, restaurants, and clubs. The resulting outcry from “respectable” members of the community helped sway public opinion against such routine civil rights abuses.

Liberal activism, however, soon gave way to more militant calls for gay liberation. The shift happened gradually. In 1966, at Compton’s Cafeteria on Turk and Taylor Streets in San Francisco, gay patrons fought back when police raided the premises. In 1967, after several police raids of Los Angeles gay bars, several hundred protestors gathered on Sunset Boulevard to demand freedom from harassment. Predating New York’s 1969 Stonewall uprising against anti-gay police harassment, usually cited as the catalyst for the gay liberation movement, these two events signaled a radical departure from the old politics of inclusion. A younger generation, influenced by the counterculture’s rebellion against “uptight” sexual mores, and minority demands for “power,” would soon call for more than acceptance into the mainstream. Asserting that “Gay Is Good,” and demanding “complete sexual liberation for all people,” they urged gays and lesbians “Out of the Closets and Into the Streets.”