11.1: Seeds of Change

- Page ID

- 127021

The decade’s social movements began with the African American and farm worker struggles for social, economic, and political equality; growing opposition to the war in Vietnam; and the emergence of the counterculture. These movements, unfolding almost simultaneously, created the foundation for others that occurred later in the decade, as well as a conservative backlash against perceived chaos and disorder.

From Civil Rights to Civil Unrest

During the early 1960s, California’s civil rights activists had reason to be optimistic. In 1959, the state legislature passed laws prohibiting discrimination in employment, public accommodations, and business transactions. The Rumford Fair Housing Act, passed in 1963, banned racial discrimination in housing. Moreover, a few cities had started to address the problem of de facto school segregation by adopting various integration plans like busing students to schools outside of their mostly all-white or all-black neighborhoods. Not all Californians, however, complied with the new legislation or approved of school integration. In response, black activists, white liberals, and idealistic youths joined forces to combat persistent patterns of racial discrimination.

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which had a long history of civil rights activism in the Northeast and South, contributed to the leadership of California’s emerging struggle for racial equality. Like their parent organization, the state’s first CORE chapters adopted the philosophy and tactics of Gandhian nonviolence and worked closely with older civil rights organizations like the NAACP. In 1963, for example, CORE activists joined the NAACP in a series of protests against housing discrimination and de facto school segregation in Los Angeles. To the north, in the Bay Area, CORE and its supporters focused on employment discrimination, organizing pickets and sit-ins at businesses that refused to hire black workers. Mel’s Drive-In chain, the target of an extensive picket campaign in 1963, was forced to revise

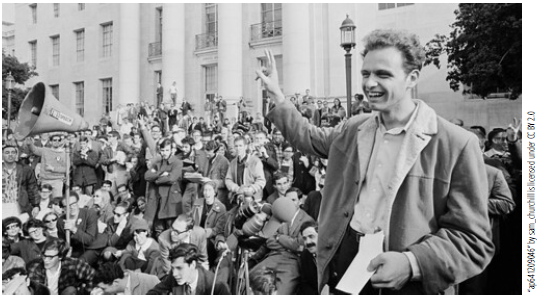

Berkeley Free Speech demonstration. The 1964 Free Speech Movement on the U.C. Berkeley campus ushered in a decade of political and cultural activism among young Californians. How do you think older residents reacted to images of young, relatively privileged college students challenging the authority of university administrators and the Board of Regents?

its hiring policies. The following year, CORE organized protests against Lucky supermarkets, Bank of America, the Sheraton Palace Hotel, and automobile dealerships with similar results.

These modest and often token victories convinced movement participants that America’s democratic promise might soon be extended to all citizens. National events contributed to their euphoria and sense of possibility. The civil rights movement in the South was forcing an entire nation to confront its history of racial discrimination and violence, and generating an unprecedented level of unity among white and black activists. And a new president, Lyndon B. Johnson, not only responded with federal civil rights legislation, but also promised to wage an all-out “War on Poverty.” For the thousands of ghetto residents trapped in poverty, Johnson’s economic opportunity bill raised hope that their government had not forgotten them. The Economic Opportunity Act, passed in August of 1964, established the Job Corps to train youths for gainful employment, VISTA (a domestic version of the Peace Corps), and a Community Action Program that provided millions of dollars in federal aid to impoverished areas. To be eligible for Community Action funding, cities had to comply with a “maximum feasible participation” mandate that involved the poor in the allocation and administration of anti-poverty monies. This, too, helped convince activists and ghetto residents that change was possible.

By late 1964, however, optimism began to fade. In November, California’s voters repealed the Rumford Fair Housing Act by approving Proposition 14, a ballot initiative sponsored by the state’s real estate industry. The proponents of the proposition claimed that government had violated the sacred right of citizens to do what they wished with their own property. In reality, however, the initiative’s backers wanted to preserve all-white neighborhoods from black encroachment and the perceived threat of declining property values. For civil rights activists and ghetto residents, the message was clear: Californians, by a two-to-one margin, had registered—in Pat Brown’s words—a “vote for bigotry.” Although the state supreme court reinstated the Rumford Act in 1966, a decision upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967, the damage had been done.

At the same time, the War on Poverty, which had promised relief to the state’s ghetto residents, was off to a rocky start. In Oakland, one of the first cities in the nation to receive federal anti-poverty funds, the mayor handpicked members of the Economic Development Council, the agency responsible for deciding how federal monies would be allocated. As a consequence, federal funding was diverted into large-scale capital improvement projects that had little impact on living conditions in poor neighborhoods. Even job training programs generated disillusionment. Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, two young participants in the city’s War on Poverty program, soon concluded, “employment training programs have become an acknowledged hustle, since few jobs are available at the end of the training program.” Like others of their generation, they had observed the negative impact of white and capital flight from their community, and they recognized that jobs, rather than job training, were crucial to their survival.

Nevertheless, Oakland’s share of federal funding did provide some relief. This was not the case in Los Angeles, where War on Poverty funds were held up because city officials refused to comply with the maximum feasible participation mandate of the federal government. By the long, hot summer of 1965, residents of Watts had ample reason to be angry and frustrated. Freeways separated their community from the rest of the city. Urban renewal programs had destroyed black businesses and affordable housing. Jobs and white residents had fled to the suburbs, leaving ghetto residents with few employment opportunities, underfunded all-black schools, deteriorating public facilities, and overcrowded, dilapidated housing stock. Housing discrimination, recently upheld by Proposition 14, and a woefully inadequate public transportation system cut off all avenues of escape. City officials, by failing to obtain federal relief monies, contributed to the growing sense of isolation and despair felt by many Watts residents. Finally, the Los Angeles police department was more intent on containing black residents in the ghetto than in protecting their lives and property. African American citizens repeatedly accused officers of ignoring due process, excessive use of force, and being “disrespectful and abusive in their language or manner.” Viewed as a brutal, occupying army, the mostly white police department served as a catalyst for mounting anger. Although city officials initially blamed the ensuing uprising on “riff raff,” it was clearly rooted in chronic, systemic neglect of black neighborhoods.

On Wednesday, August 11, 1965, police patrolling Watts arrested Marquette Frye and his brother for drunken driving. Frye’s mother, who arrived at the scene with several other observers, was handcuffed when she protested the arrests. Bystanders reported that the police hit Marquette on the head, placed a gun to his temple, and roughly tossed all three family members into an officer’s car. The crowd was further inflamed by a rumor that police had attacked an innocent onlooker. More residents soon gathered as charges of police brutality circulated through the neighborhood. Alarmed officers radioed for backup, but the increased police presence and overreaction provoked the crowd. That evening, violence broke out but was contained within a small area and largely limited to attacks on police officers, white drivers, and television crews. The following day, African American community leaders, fearing the worst, appealed to police to replace white patrols with African American plainclothes officers and convinced the media to allow a respected minister to make a televised plea for peace. Both measures failed. The Los Angeles Police Department refused to assign African American officers to Watts, and the minister’s appeal aired before most viewers had tuned in for the evening.

Beginning on Thursday night and lasting until Monday morning, the Watts uprising took a heavy toll. Crowds moved into the vicinity of the initial altercation, spread out into central Watts, and then moved outward, toward downtown Los Angeles. Venting years of anger and frustration, nearly 10,000 participants looted and burned hundreds of mostly white-owned businesses, resulting in $40 million in property damage. After order was restored by the National Guard, at least 34 had died, 31 of them black. Hundreds of others were seriously injured, and almost 4000 had been arrested. Although many participants claimed that the riot had forced whites to take note of ghetto conditions, the uprising produced few concrete changes. City officials created a board to administer anti-poverty funds immediately after the riot, providing short-term relief to residents; however, little was done to address chronic unemployment, de facto school segregation, housing discrimination, and police brutality. Watts, like the state’s other black ghettos, stood in stark contrast to the burgeoning, prosperous suburbs.

The riot, however, marked a transition from nonviolent civil rights activism to more militant assertions of Black Power. Proposition 14, which repealed the Rumford Fair Housing Act, was identified as a contributing cause of the uprising, and it provided tangible evidence of white hostility to racial equality and integration. Moreover, the riot exposed conditions in Watts that clearly defied liberal solutions. African Americans, raised in impoverished inner cities, derived little comfort from Lucky’s promise to hire more black workers. Not only did ghettos lack supermarkets where residents could buy fresh, affordable food; they also lacked the public transportation systems that linked workers to jobs. As one black leader observed toward the end of the ’60s, the earlier generation of activists “retained their profound faith in America, her institutions, her ideals, and her ability to achieve someday a society reflecting those ideals.” Increasingly, however, “there is a growing and seriously held view among some militant Negroes that white people have embedded their own personal flaws so deeply in the institutions that those institutions are beyond redemption.”

Black Power

Throughout the nation, from California’s inner cities to the Mississippi Delta, young activists embraced more radical solutions to persistent patterns of racial discrimination—solutions that turned on the slogan “Black Power” and included militant assertions of cultural pride, community self-defense and determination, solidarity with Third World peoples, and socialist critiques of capitalism. The shift away from nonviolent civil rights activism to black selfdetermination alienated many formerly sympathetic whites and liberal black leaders from the emerging movement. For years, white and black activists had worked together toward the goal of creating an integrated, color-blind society. Now a new generation of black youths insisted on “the right for black people to define their own terms, define themselves as they see fit.”

In the fall of 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, two young Merritt College students, founded the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California, and articulated this new agenda. The Panthers’ platform demanded full employment, decent housing, an end to police brutality, the “power to determine the destiny of our community,” and education that “teaches us our true history and our role in the present-day society.” It also called on the government to release black people from prison “because they have not received a fair and impartial trial,” and demanded exemption from military service because “we will not fight and kill other people of color in the world who, like black people, are being victimized by the white racist government of America.” What shocked more moderate citizens, however, was the organization’s position on selfdefense. Citing the Second Amendment of the Constitution, the Panthers asserted their right to bear arms in defense of “our black community from racist police oppression and brutality.”

Upon forming the party, Newton and Seale recruited residents of Oakland’s ghetto to trail police and ensure that officers did not violate the constitutional rights of those they questioned or arrested. These citizen patrols, armed with guns and legal statutes, captured the media’s attention and overshadowed the party’s less controversial after-school and free-breakfast programs for children, community clinics, voter registration drives, and concern for education and prison reform—programs that contributed to its positive image in black communities. The Panthers, however, often encouraged

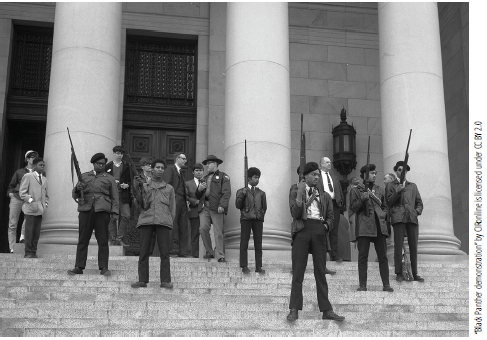

Black Panther demonstration. Photographs like this one, often underscored the anger and assertiveness of Black Power activists. How do you think white Californians reacted to such images?

publicity that emphasized their militancy. In 1967, as the state legislature debated a new gun control measure aimed at curbing their activism, armed party members converged on the state capitol and demanded access to the proceedings.The confrontation, aired on the national news, contributed to the organization’s growing popularity with radical youth, but fueled white fears of black insurrection. The police, sharing this fear, intensified their efforts to suppress the party, leading to a series of violent confrontations where the distinction between victim and perpetrator was often blurred. In 1967, Huey Newton, the party’s minister of defense, was arrested following an altercation with the Oakland police that left one officer dead and Newton and another officer injured. Charged and convicted of manslaughter, Newton later won release because of ambiguities in police evidence and testimony. In 1968, the party’s minister of education, Eldridge Cleaver, was arrested following another confrontation with the Oakland police in which two officers were wounded and a Panther killed. Cleaver, free on bail, ran as the Peace and Freedom Party’s presidential candidate in 1968, but later fled the country to avoid what many activists believed would be a politically charged trial.

As the Black Panther Party spread across the nation, federal, state, and local governments took extreme and sometimes illegal measures to curb militant activity. The FBI, which regarded the Panthers as a threat to internal security, used paid informants both to supply detailed intelligence and to instigate violence where police use of excessive force could be justified. In 1968 alone, local police across the nation killed 28 Panthers and arrested hundreds of others. By the mid-1970s, the party was in disarray, torn apart by bloody confrontations with law enforcement, internal divisions, and the deaths or imprisonment of its leadership.

The Black Panther Party, while relatively short-lived, left a lasting imprint on California politics. The party’s emphasis on community empowerment encouraged the black electorate to demand a greater share of political power in the nation’s inner cities. In Oakland, for example, the party encouraged residents to challenge the mayor’s policy of hand-picking the Economic Development Council, the agency that allocated War on Poverty funds. By 1967, citizens gained control of the Council and began redirecting money to neighborhood-based development projects. Emboldened by this victory, the party moved on to electoral organizing, registering 30,000 new voters for the 1972 mayoral election. Stunning the city’s political establishment, Bobby Seale, the Panthers’ candidate for mayor, came in second, drawing 43,749 votes to the Republican incumbent’s 77,634. The Panthers went on to help organize voter support for John George, who became Alameda County’s first black supervisor in 1976, and Lionel Wilson, who became Oakland’s first black mayor in 1977. Gains on the federal and state levels were equally impressive. In 1970, the black vote sent Ronald Dellums to Congress and seated Wilson Riles as State Superintendent of Public Instruction. In 1972, Yvonne Burke followed Dellums to Washington, and Mervyn Dymally, seated as lieutenant governor, joined a growing contingent of black legislators in Sacramento. Just as significantly, the Panthers’ demand for “an educational system that will give our people a knowledge of self” helped ignite the student movement for black and ethnic studies programs and a more general assertion of cultural pride and identity. Finally, the Panthers’ anti-police brutality campaign led to the establishment of citizen review boards and affirmative hiring policies in local law enforcement agencies.

Municipal power, however, raised a thorny question—one that is still unresolved. According to one observer, cities like Oakland had merely fulfilled “a cynical prediction of the central cities of the future; that as blacks and other minorities gain political office and a voice in governmental affairs, whites exodus out to the suburbs, and most importantly the major industries which carry a large load of the tax burden follow them. Non-whites gain office to control, but they in effect control nothing because there are no industries and no money. The city becomes yet a larger ghetto, controlled and dependent upon forces from outside.” As the Black Power movement waned, California’s African American population turned elsewhere for solutions to the state’s continuing racial dilemma.

The Grassroots War on Poverty

Poverty in California’s inner cities generated yet another movement of national significance, one that united women of all ethnicities. The welfare rights movement began in Alameda County in 1962 when fire struck the house of a welfare recipient. The welfare office withheld the woman’s monthly check because “she was living in unfit housing.” With seven young children in her care, the woman desperately turned to other recipients who then began to share similar stories of callous and disrespectful treatment. A permanent organization soon took root, spreading to inner cities throughout California. One of their earliest battles took place in Alameda County. In 1964, the state ended the bracero program, which had transported more than five million Mexicans to work in California’s fields. Strawberry growers in the northern part of the state complained of labor shortages. Shortly thereafter, the county sent notice to welfare recipients that they would lose their benefits if they failed to take field jobs; however, if recipients took such work, they would be identified as “gainfully employed” and would still lose their benefits. Simultaneously, the county began withholding public assistance from new welfare applicants, claiming that agricultural jobs were readily available. The new Welfare Rights Organization (WRO) responded by stating that recipients, many of whom were skilled and semiskilled workers displaced by capital flight to the suburbs, would not be able to find substitute, higherpaying jobs in manufacturing if forced to work in the fields. The WRO then staged a sit-in at the county welfare office and threatened to take similar action in front of the state welfare department in San Francisco. As a consequence, the state allowed those who took agricultural jobs to retain their benefits, but still failed to address the more serious problem of forcing displaced workers into low-wage farm labor.

Emboldened by their partial victory, the WRO went on to lobby successfully for increases in general assistance, an end to waiting periods or residency requirements for benefits, and a complete ban on mandatory farm labor during all but the summer months. Even more significantly, welfare recipients began to challenge the authority of social service providers and the mythology that poor people are responsible for their own condition. As one WRO activist stated, “We are human beings just like everybody else…. We don’t get the taxpayers’ money free. We play the lowest games to get that money. You have to be harassed the whole month to get $200 from the welfare.” She went on to enumerate the obstacles women faced in finding gainful employment, including lack of funds for transportation and child care. For her and other welfare recipients, however, the bottom line was the lack of decent-paying employment within inner cities. As the WRO spread across the nation, attracting thousands of members and support from progressive organizations, it successfully lobbied for increased aid and the liberalization of eligibility requirements. While this provided immediate relief to many impoverished families, it failed to stem the continuing economic decline of urban ghettos. By the mid-1970s, the movement and its hard-won gains fell victim to the recession and fiscal conservatism of a new federal administration.

Justice in the Fields

In the midst of growing urban unrest, Cesar Chavez launched a revolution in California’s fields. After serving in the Navy during World War II, Chavez rejoined his family in Delano, married, and started a family. Seeking a way out of the grinding poverty and unrelenting toil that circumscribed the lives of California’s farm workers, he moved his growing family to the San Jose barrio of Sal Si Puedos, found work at a lumber mill, and joined a newly formed chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO). Initially, Chavez worked as a CSO volunteer, registering Mexican American voters in San Jose. His tireless dedication, however, soon led to a paid position as a statewide organizer, and ultimately to appointment as CSO’s national director.

As he rose through CSO’s ranks, focusing primarily on increasing the electoral power of urban Latino voters, Chavez became more and more convinced that political and economic justice were entwined—particularly in the state’s rural agricultural communities. There, growers used braceros and undocumented immigrants to undercut the wages, working conditions, and bargaining power of domestic workers. In the process, all three groups suffered. In 1962, at the annual CSO convention, Chavez presented a plan to create a farm workers’ union and was voted down. With only $900 in savings, eight children, and the support of his wife, Helen, Chavez resigned from the CSO and moved back to Delano. When he returned to Delano in April of 1962, farm workers’ living and working conditions were much the same as they had been two decades earlier. Federal and state laws that granted other workers a minimum wage, social security, unemployment insurance, and the right to organize and bargain collectively did not apply to agricultural labor. And the bracero program, providing growers with an unlimited, subsidized work force, kept wages for domestic workers artificially low and made unionization virtually impossible. Against these odds, Chavez began to build a grassroots union that was philosophically committed to participatory democracy, dignity for the common person, nonviolence, and multiethnic unity and cooperation.

With a small team of talented organizers, including Dolores Huerta, Gilbert Padilla, Julio Hernandez, and Jim Drake, Chavez slowly built the organization’s membership by going from door to door and town to town, and providing practical services to farm worker families. By September of 1962, the union had built a strong enough base to hold its founding convention. There, delegates voted to name the organization the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), adopt the black eagle against a white and red background as its emblem, and accept “Viva la Causa” as the union’s motto. Delegates also approved monthly membership dues of $3.50 and elected Chavez as president, and Huerta and Padilla as vice presidents.

The new organization, while attracting additional members and volunteers, barely survived the next two years. By 1965, however, the tide had turned. The government finally terminated the bracero program, making it more difficult

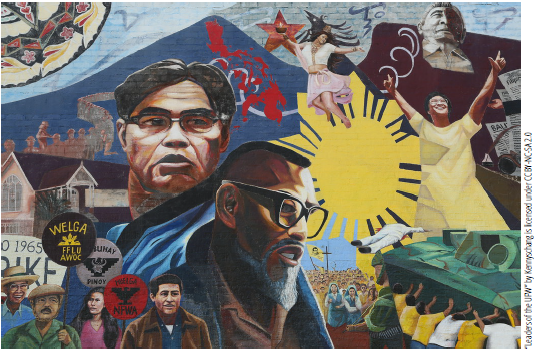

Shown here is a contemporary mural depicting Larry Itliong, Cesar Chavez, and other key figures in the 1965 Grape Strike. What does this image convey about the people who participated in this struggle?

for growers to use an imported labor force to break strikes and block unionization efforts. The nonviolent civil rights movement in the South had also captured national attention and created a groundswell of public concern over social and economic inequalities. Liberal Protestant and Catholic clergy and student activists who had championed racial justice in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi now had a compelling cause much closer to home.

The catalyst for liberal support was the Delano Grape Strike, initiated by Filipino farm workers on September 8, 1965. Growers in the San Joaquin Valley, determined to keep wages low, continued to pay domestic workers less than what braceros had received. In response, Filipino members of the Agricultural Workers’ Organizing Committee (AWOC), an AFL-CIO affiliate, voted to strike. Their demand was wage parity with braceros, or a modest $1.40 an hour. The growers, including agribusiness giants like the Di Giorgio Corporation, not only refused to meet their demands, but also evicted Filipino workers from labor camps and called in the local police to intimidate strikers. Larry Itliong, the leader of the strike, turned to the fledgling National Farm Workers Association for support. Chavez, in a rousing appeal to his membership, stated: “The strike was begun by Filipinos, but it is not exclusively for them. Tonight we must decide if we are to join our fellow workers in this great labor struggle.”

The strike soon gained national attention and support. Student volunteers and clergy flocked to Delano to offer their assistance and helped raise money in college communities and among their congregations. Unions, including the formidable United Auto Workers, pledged their financial support and generated sympathy for “la Causa” among urban blue-collar workers. Luis Valdez, a member of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, returned to his roots in Delano and organized El Teatro Campesino (the farm worker theater) to dramatize the unfair treatment of farm labor. El Teatro, which performed to migrant audiences in the fields, helped recruit union members. Its actors, all campesinos, also toured college campuses, urban barrios, and various towns and cities to raise funds for the strike. Finally, Chavez called on the public to support a national boycott of products produced by Delano’s largest growers.

Additional support flooded in during and after the union’s 25-day procession from Delano to Sacramento in the spring of 1966. Carrying union banners, images of the Virgin of Guadalupe, and Mexican and American flags, striking workers and their supporters made the 250-mile journey in the spirit of a religious pilgrimage, as “an excellent way of training ourselves to endure the long, long struggle.” Many who witnessed the march as it aired on the evening news or passed through local communities were deeply moved by the spiritual discipline, humility, and poverty of the participants. The farm workers who made the journey had indeed drawn strength from their Catholic religious traditions to endure the economic hardship of a prolonged strike. Many had lost their homes and were forced to rely on the union’s meager resources for food, clothing, and shelter.

The march touched America’s moral conscience and placed additional pressure on growers to meet the strikers’ demands. Even before the procession reached Sacramento, Schenley Corporation, a producer of wine grapes, gave formal recognition to the union by signing a contract. A rumor that New York bartenders were planning to boycott Schenley products, and the Teamsters’ Union’s refusal to cross picket lines at the company’s San Francisco warehouse, helped convince Schenley to enter into the agreement. Soon after, other major winemakers, including the Christian Brothers, Almaden, Paul Masson, Gallo, Franzia, and Novitiate, signed contracts. Di Giorgio, whose products were marketed under the S&W and Tree Sweet labels, agreed to allow its workers to vote on whether they wanted union representation.

The Teamsters’ Union, which had backed the strike, became increasingly concerned that the NFWA’s organizing efforts would disrupt the work schedules of its packers and truckers and place a drain on union resources. Thus, the Teamsters, in collusion with Di Giorgio, announced that it would compete with the NFWA to represent workers in the upcoming election. Worried that a Teamsters victory might result in a “sweetheart” contract that would fail to improve the wages and working conditions of agricultural labor, the NFWA decided to merge with AWOC to create a united front, affiliated with the AFL-CIO, against their new opposition. Their strategy succeeded. In the August 1966 election, Di Giorgio’s workers returned 331 votes in favor of Teamster representation and 530 votes for the newly formed United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC-AFL-CIO). Even after farm workers voted in favor of union representation, however, Di Giorgio failed to reach an agreement with UFWOC until April 1967.

Despite these major gains, the majority of the state’s table grape growers refused to recognize or negotiate with the UFWOC. In 1968, Chavez mounted a national boycott against all table grapes that forced most of the remaining growers to sign contracts with the union by July 1970. The victory, representing the greatest advance for farm labor in American history, came at a high price. In Chavez’s words: “Ninety five percent of the strikers lost their homes and cars. But I think that in losing those worldly possessions they found themselves, and they found that only through dedication, through serving mankind, and, in this case, serving the poor, and those who were struggling for justice, only in that way could they really find themselves.”

The Anti-War Movement

The civil rights, Black Power, and farm workers’ movements of the ’60s paralleled America’s growing involvement in the Vietnam War. Although a broadcross section of California’s population joined anti-war protests, students formed the backbone of the movement. By 1965, campus teach-ins on America’s role in Vietnam crystallized student opposition to the war. And for the next seven years, activists tried to disrupt “business as usual” on college campuses and in surrounding communities. Their protests, while convincing many citizens and policymakers that unrest at home was too high a price to pay for the war abroad, prompted others to call for the restoration of law and order. Combined with ethnic power movements, the anti-war opposition polarized the state’s residents and destroyed the last vestiges of the postwar liberal consensus.

Emboldened by their free speech victory at the end of 1964, Berkeley students embraced a new cause. In the spring of 1965, more than 12,000 students and faculty held a two-day teach-in on the Vietnam War. A series of protests followed, directed at the university’s ROTC program, military-related research, and policy of allowing defense industry job recruiters on campus. Their antiwar fervor was also fueled by California’s role as a major staging ground for the war in Southeast Asia. Troops, supplies, and military hardware were all deployed from state bases, often along highly visible rail lines and roadways. Teach-ins and protests soon spread to other colleges, creating the foundation for a statewide anti-war movement.

By 1967, many students throughout California had joined the Resistance, an anti-war organization that coordinated anti-war demonstrations, and called on its supporters to “move from protest to resistance.” In October of

1967, during “Stop the Draft Week,” protestors marched on the Oakland Induction Center, where draftees and recruits were processed for military service. Police in riot gear blocked their attempt to surround and shut down the center. The protestors, however, donning hard hats and homemade shields, regrouped and briefly took control of the facility and surrounding neighborhood following a pitched street battle with the vastly outnumbered police.

Other protests, often violent and confrontational, followed the Tet Offensive in 1968, the U.S. invasion of Cambodia in 1970, and the release of the Pentagon Papers and the U.S. invasion of Laos in 1972. When the war finally ended in 1973, it had taken a frightening toll. Military expenditures had diverted resources from anti-poverty programs and plunged the state into economic recession. Thousands of young Californians lost their lives in the war, and those who survived received little assistance in coping with physical and psychological trauma. By 1979, when Congress finally appropriated funds to provide outreach services to veterans, many had already suffered irreversible damage from substance abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, and exposure to the defoliant known as Agent Orange.

The anti-war movement also exposed deep political rifts. Many oldguard liberals and labor leaders were unwilling to break ranks with Lyndon B. Johnson over his foreign policy. On the other hand, left-wing Democrats called for an end to the conflict and a renewed commitment to ending racism and poverty. By the end of the decade, the Democratic Party, on both state and national levels, was deeply divided. Conservative Republicans capitalized on this division and the mounting fears of many ordinary Californians to create a new coalition of “Forgotten Americans”— Americans who were more concerned about curbing government expenditures and militant protest than social and economic reform. This coalition, abandoning the liberal agenda of the postwar era, would shape state and national politics for years to come.

Although many youths retained their commitment to nonviolent social change, they had grown more suspicious of their government. Indeed, some members of the protest generation lost faith in political leaders and institutions and launched violent attacks against the “establishment.” For example, the Symbionese Liberation Army, a small fringe group that viewed itself as the revolutionary vanguard, assassinated Oakland School Superintendent Marcus Foster, robbed a series of banks, and kidnapped newspaper heiress Patricia Hearst. After a violent confrontation with police in 1975, the “Army” briefly regrouped, robbing more banks and killing a female bank customer, before its remaining members were arrested or driven into hiding. Four members of the group, who remained in hiding until recently, were finally caught, prosecuted, and sentenced in 2001 and 2002.

The Counterculture

By mid-decade, growing numbers of young Californians embraced cultural rebellion as well as political protest. The Vietnam War, persistent patterns of racial discrimination, the conservative social values of the older generation, and disillusionment with mainstream political leadership prompted many youths to experiment with alternative lifestyles. Accusing their elders of creating a society based on material greed, competition, violence, and the repression of emotion and sexual desire, these cultural rebels sought liberation through communal living, free love, “mind-expanding” drugs, and psychedelic music. By separating themselves from the world of their parents, they hoped to create a parallel, or counter, culture that would serve as a model to the rest of society. Although some abandoned electoral politics and political protest as an avenue of social change, they nonetheless saw themselves as activists—as pioneers of a new, more peaceful, spiritual, and egalitarian social order.

An earlier generation of cultural rebels, the Beats, played a pivotal role in launching the state’s countercultural revolution. In 1963, novelist Ken Kesey used the profits from his book, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, to start a commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Its members, calling themselves the Merry Pranksters, toured around the state in a brightly painted bus championing the virtues of psychedelic drugs and flouting middle-class behavioral conventions. Using LSD, a hallucinogenic drug produced by Augustus Owsley Stanley III, the son of a U.S. senator, the Pranksters went on to sponsor a series of “acid tests.” Participants, often numbering in the thousands, danced to new bands like the Grateful Dead while under the influence of LSD that had been provided by “test” organizers. From that point on, hallucinogenic drugs became an integral part of the decade’s cultural revolt. Following the lead of Kesey and Harvard psychologist-turned-drug-prophet Timothy Leary, young rebels sincerely believed that psychedelic drugs were a gateway to higher consciousness, the key to creating a social order based on cooperation, sensual openness, creative expression, and unity with nature.

By the mid-’60s, San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury District became the center of the emerging counterculture. Lined with communal “crash pads,” drug paraphernalia and poster shops, hip clothing boutiques, bead stores, and a growing contingent of longhaired, colorfully attired “flower children,” its streets attracted national media attention. Much of the publicity emphasized the kooky and seamy side of the hippie lifestyle, portraying its adherents as unkempt, drugged-out hedonists. But this only added to the Haight’s mystique among the young who flocked to San Francisco by the tens of thousands. This influx was so significant that it was popularized in a hit song. Musician Scott MacKenzie, in “Are You Going to San Francisco,” urged the would-be traveler to “be sure to wear flowers in your hair.”

A new form of rock music, often performed in accompaniment with light shows, also helped establish San Francisco as the center of the countercultural revolution. The “San Francisco sound,” or acid rock, developed by local bands such as the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Country Joe and the Fish, and Big Brother and the Holding Company not only celebrated drug use but also underscored other themes of the movement: peace, open sexual expression, racial unity, cooperation, and alienation from mainstream society. Performed at San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium, Avalon Ballroom, and outdoor parks and amphitheaters, the music drew thousands of youths together in celebration of their new collective identity. Like drugs, rock music was viewed as an agent of social liberation. In the words of Ralph Gleason, a local music critic, “at no time in American history has youth possessed the strength it possesses now. Trained by music and linked by music, it has the power for good to change the world.” Many older Americans saw things differently. Whereas the Beach Boys promoted a wholesome, “fun in the sun” image of California, these bands seemingly encouraged reckless experimentation with sex and drugs, and rebellion against parental authority.

Sexual experimentation now entailed a lower risk of pregnancy because of the development of reliable contraceptives, and thus it became the third cornerstone of the youth culture. Public nudity, casual sex, open displays of affection, and the use of sexually explicit language were viewed as political attacks against “uptight Amerika” as well as expressions of personal liberation. The pursuit of sexual pleasure, however, did not necessarily include the revision of traditional gender roles. Among both political and cultural rebels, men continued to monopolize positions of authority and power and to relegate women to subordinate or supporting roles. Indeed, the anti-war movement, with its emphasis on the heroism and sacrifice of male draft resisters, relegated women’s issues and concerns to the back burner. War resistance slogans like “Girls Say Yes to Men Who Say No!” reinforced the notion that sexual availability was a measure of women’s political commitment. Within the counterculture, this pressure intensified. Women who wanted the emotional security, intimacy, and stability of monogamous relationships were accused of being repressed, uptight, or brainwashed by their puritanical parents.

Within a few years, the contradiction between the movement’s goal of creating a nonhierarchical, cooperative society and women’s lived experience generated a powerful new feminist movement. For the time being, though, youthful rebels continued to elaborate on their counterculture. The underground press, including the Los Angeles Free Press, the Berkeley Barb, and the San Francisco Oracle, promoted both political and cultural defiance. Similarly, underground posters, comics, radio, film, and theater disseminated alternative values and reinforced a shared sense of purpose and unity. Urban and rural communes proliferated throughout the state as hippies or flower children sought to live their vision of a more humane, cooperative, decentralized social order. The Diggers, a San Francisco anarchist group, provided free food on the streets and in parks. People discarded unwanted clothing in “free boxes.” And sympathetic health professionals organized free clinics.

By the end of 1969, however, the counterculture was in decline. The “Summer of Love” had attracted thousands of young people to San Francisco, along with drug addicts, dealers, and petty criminals. Idealistic youths, including growing numbers of runaways, were easy targets for more sophisticated criminals, leading one participant to observe: “Everybody knew that the scene had gotten so big that they’d destroyed it. Too many people. Too many runaways. Drugs were getting pretty bad. Heroin was showing up. The street carnivals were crazy.” By December, two events marked “The End of the Age of Aquarius”: the violence at the Rolling Stones’ Altamont concert and the grisly Charles Manson murders. At Altamont, the Stones hired members of the Hollister-based Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang to provide “security.” The Angels, high on beer and drugs, and armed with clubs, terrorized and assaulted the audience and stabbed one young man to death. Two other people died when a car ran into a crowd, and another person— high on drugs—drowned in an irrigation ditch. In contrast to the peaceful Woodstock concert earlier in 1969, Altamont exposed a dangerous, violent side to the counterculture. Manson, a self-proclaimed countercultural prophet, attracted a small but devoted following to his southern California commune with drugs, free love, and his psychotic preaching. From there, he and his “family” committed a series of brutal murders, including the ritualistic killing of pregnant actress Sharon Tate. Although these two events shocked the public, and contributed to growing skepticism of the “love generation’s” values, the counterculture found a final cause before it completely disintegrated in the early 1970s.

Coming Together at People’s Park

Although many cultural rebels withdrew from politics and emphasized building alternative institutions, most were active participants in anti-war protests and other political struggles. Similarly, most political activists crossed over into the counterculture, adopting various aspects of the hippie lifestyle. The convergence of the two took concrete form in the battle over People’s Park. In late April of 1969, Berkeley students and community activists took possession of a vacant lot owned by the University of California. After clearing the site of debris, activists planted trees, grass, and flowers, and set up playground equipment, a stage area for musical and street theater performances, and a distribution station for free clothes and food. Political radicals and cultural rebels, more cynical toward authority than they had been during the Free Speech Movement, viewed the seizure as an act of defiance against the university—an institution that devoted its resources to military- and corporate-sponsored research, and to educating a new generation to assume leadership roles in the “establishment.” Confrontation, rather than a last resort, was now the preferred plan of action. Many activists, however, also viewed their actions in productive or creative terms. Working cooperatively and democratically, they had transformed a barren, trash-strewn lot into a People’s Park. If the youth were in charge, they asserted, the world would be a greener, kinder, and more egalitarian place.

University administrators, city officials, and many local business leaders saw things differently. The seizure of university land not only violated private property rights but also revealed the contempt that youths had for adult authority. Moreover, the park threatened to attract an even larger number of hippies and longhaired radicals to the community. On May 15, after the Highway Patrol and Berkeley police cleared the site and constructed a fence around the perimeter, 6000 demonstrators marched down Telegraph Avenue to “liberate” People’s Park. Police fired tear gas to disperse the crowd, and protestors retaliated by throwing rocks, breaking store windows, and setting trash containers on fire. As the violence escalated, police sprayed demonstrators with buckshot, blinding one man, killing another, and injuring more than 100. By evening, Governor Reagan called in the National Guard to restore order.

Protestors, however, continued to gather at the park on a daily basis, in a nonviolent but uneasy standoff with the “occupying” army. This battle of nerves culminated in more violence on May 20, when the National Guard blocked the southern entrance to the campus and used helicopters to drop tear gas on hundreds of students trapped in the university’s Sproul Plaza area. This show of force horrified many Berkeley residents and generated widespread sympathy for the protestors. On May 30, 30,000 people took part in a march to the park in memory of James Rector, the protestor slain on May 15. Although peaceful, this protest ushered in three years of ongoing conflict over the site. In May 1972, after Nixon announced his intention to mine North Vietnam’s main port, demonstrators converged on the park and finally succeeded in tearing down the fence. Shortly after, the Berkeley City Council voted to lease the land from the university and assume responsibility for its upkeep. For the time being, the “people” had won.