10.3: Social and Cultural Dissent

- Page ID

- 127019

The postwar period, although an era of relative economic prosperity, social harmony, and political stability, contained the seeds of conflict. While the middle class expanded, largely because of state and federal investment in housing, education, and the military-industrial complex, poverty and racial discrimination remained serious problems. The suburban boom, a symbol of the era’s prosperity and stability, bypassed ethnic minorities and the poor, and took— as many were beginning to recognize—a tremendous toll on the environment. Even gender roles were in flux, as increasing numbers of married women entered the work force or confronted the isolation, boredom, and lack of status associated with suburban domestic roles. The political arena was also charged with tension, roiling with anti-Communist hysteria, blatant opportunism, and bitter contests between liberal and conservative forces. Only in 1958 did the state approach anything remotely resembling a political consensus.

White Flight and Ghettoization

The state’s black population continued to expand during the postwar period, fueled by the baby boom and a steady stream of opportunity-seeking migrants. By the mid-1960s, reflecting a decade of gradual progress, African Americans held four state assembly seats, representing the 17th District in Alameda County, the 18th District in San Francisco County, and the 53rd and 55th Districts in Los Angeles County. Augustus Hawkins, who had served in the assembly since 1934, became California’s first black congressman in 1962. Local gains were also impressive, with African Americans obtaining city council seats in Los Angeles, Compton, and Berkeley; school board seats in Oakland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Berkeley; and one seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

These political advances translated into important civil rights victories, particularly on the state level. In 1959, the legislature banned employment discrimination and created the Division of Fair Employment Practices to enforce the new law. It also passed the Unruh Civil Rights Act prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations, business transactions (including real estate), and public housing. Fair housing legislation, although meeting with greater white resistance, followed in 1963. Finally, several municipalities adopted civil rights measures of their own. San Francisco, for example, created a Fair Employment Practices Commission in 1958, and Berkeley enacted a fair housing law and school integration plan in 1963.

Fair employment legislation, combined with political pressure from civil rights groups, produced the most immediate results. State, county, and local government, which expanded rapidly during the postwar period, adopted nondiscriminatory hiring policies in advance of private industry. As a consequence, increasing numbers of African Americans gained access to civil service employment—jobs that offered relatively high wages and occupational security and contributed to the growth of California’s black middle class.

The political progress that produced such gains, however, was partly a product of black ghettoization. African Americans won representation not in the booming, prosperous suburbs, but in the urban core and within the confinesof well-defined black districts or neighborhoods. Fair employment legislation, all too easily circumvented by private employers, did even less to prevent industry from following whites to the suburbs. And fair housing legislation, which should have allowed minorities to participate in the suburban boom, met with bitter opposition and organized resistance. Even after the courts upheld the law, homeowners and lending and real estate agencies continued to ignore its directives. Most African Americans, regardless of their economic status, were trapped.

As white and industrial flight to the suburbs stripped California’s inner cities of their tax and employment base, those who remained behind faced increasingly bleak futures. By the mid-1950s, the postwar ghetto had taken shape, characterized by high levels of joblessness, dilapidated housing, inadequate police and fire protection, poor recreation facilities, and limited medical and shopping establishments. The spatial and economic marginalization of ghettos was compounded by government-financed freeway projects that destroyed entire black neighborhoods and business districts, and cut residents off from the rest of the city. By 1960, for example, the Watts section of Los Angeles was effectively Balkanized by the very transportation networks that facilitated white and industrial flight to the suburbs. Although 60 percent of its population was young and full of promise, astonishingly high levels of unemployment created a climate of frustration and despair. More than 40 percent of young adults were unemployed, and most of those who were fortunate enough to find jobs worked part time and for low wages.

De facto school segregation also emerged as a serious problem. Most blackchildren attended predominantly black schools, reflecting their increasing spatial isolation from other inner-city neighborhoods and the surrounding suburbs. Although a few cities adopted school integration plans in the early 1960s, most, including Los Angeles, resisted efforts to ensure educational equity well into the 1970s. Even then, citywide desegregation programs were only partially effective. Many white urbanites either placed their children in private schools or relocated to the suburbs. And predominantly white suburban districts, with a surplus of resources, continued to afford richer academic environments than their urban counterparts.

As conditions in ghettos deteriorated, many municipalities adopted urban renewal plans. These efforts to reclaim “blighted” sections of the inner city frequently entailed the wholesale destruction of entire neighborhoods. At best, older single-family homes were replaced with low-income housing projects that confined the poor to even smaller, more isolated enclaves. At worst, as was said at the time, urban renewal amounted to “Negro removal.” In West Oakland, for example, city officials razed block upon block of affordable housing without constructing an equivalent number of low-income units.

Despite the shrinking opportunity structure in California’s black ghettos, a majority of black activists embraced a civil rights–oriented agenda. Black advancement, they believed, hinged on full integration into the white mainstream—integration that could be achieved through laws that guaranteed equal access to all the rights and privileges of citizenship. By 1963, however, a new generation of activists realized that legislation alone would not eliminate racial discrimination. Some, retaining the liberal optimism of the older generation, turned to nonviolent protest to force compliance with the law. Others, particularly those who had been raised in the inner city, had less faith that whites would willingly relinquish their power, or that civil rights legislation would address the deeper, more tangled form of racism so keenly felt by ghetto residents. Postwar California, despite its booming economy and legislative commitment to racial equality, had fostered and ignored the ghettoization of black citizens. Soon the resulting rage and frustration, fueled by voter repeal of the Rumford Fair Housing Act, dispelled any lingering fantasies of social harmony and political stability.

Poverty in the Barrios and Fields

The state’s Mexican Americans experienced a similar mixture of hope and despair. During the postwar years, the Hispanic population not only increased, but also continued to cluster in urban areas. While most of this growth was concentrated in southern California, newcomers, mostly Mexican Americans from other southwestern states, settled in northern cities as well. Between 1950 and 1960, the Spanish-surnamed population more than doubled in Los Angeles, San Diego, and San José, and increased by almost 90 percent in Fresno and the San Francisco Bay area. Undocumented immigrants, sharply increasing in number following the war, also contributed to this growth and created a painful dilemma for Mexican American activists.

On one hand, undocumented immigrants exacerbated the problems created by the bracero program. They displaced domestic workers in agriculture and industry, depressed wages, undercut unionization efforts, and were perceived as undermining the efforts of long-term residents to combat negative stereotypes and enter the Anglo American mainstream. Moreover, immigration officials frequently violated the rights of citizens and noncitizens alike during neighborhood and workplace “sweeps” for undocumented residents. These Cold War–era roundups, termed “Operation Wetback” by the federal government, resulted in almost two million deportations between 1953 and 1955 and were partly intended to root out alien dissidents. On the other hand, new immigrants and Mexican Americans shared cultural, linguistic, and often family ties. If unified rather than divided by anti-immigrant hysteria, there was a potential for effective political action against prejudice and discrimination.

Regardless of their nationality, both groups did, in fact, have common concerns. By the mid-1960s, 85 percent of the state’s Spanish-surnamed population lived in cities, mostly within segregated enclaves or barrios. Like black ghettos, barrios were products of housing discrimination. And like ghettos, they were increasingly isolated from surrounding areas by freeways, and characterized by older, dilapidated housing, overcrowded and underfunded schools, inadequate recreation facilities, declining infrastructure, and high levels of underemployment and unemployment. Residents who found jobs were limited to low-paying, unskilled occupations by discriminatory hiring practices. Even the public sector, while providing new employment opportunities to other ethnic minorities, extended comparatively few jobs to Mexican Americans. Los Angeles County government, for example, employed 28,584 Anglos and 10,807 African Americans in 1964, but only 1,973 Mexican Americans. As a consequence, one in every five families fell below the poverty line, and a majority earned significantly less than the median white income.

Many city officials, rather than addressing these problems, seemed more intent on harassing residents for petty legal violations, keeping them within the confines of the communities, or erasing barrios altogether through urban renewal. In 1957, for example, Mexican American residents were forced out of Chavez Ravine to make room for the new Los Angeles Dodgers Stadium. Residents rightly suspected that their removal was part of a broader, Cold War–inspired effort to curb the growing political and social power of the Mexican American community. Councilman Edward Roybal, objecting to the treatment of a family that resisted displacement, commented: “The eviction is the kind of thing you might expect in Nazi Germany or during the Spanish Inquisition.” Even in communities not threatened by urban renewal, residents lived in a chronic state of insecurity. Immigration sweeps and high levels of police brutality and harassment convinced many that the government was an enemy rather than a friend.

In rural areas, conditions were even worse, particularly for migrant farm families. Agricultural workers, lacking the protection of minimum wage laws, earned between 40 and 70 cents an hour during the 1950s. Even if a worker was employed for 50 hours a week, 35 weeks out of the year, earnings still fell well below the official poverty level. And most workers, given fluctuations in the weather and harvest cycle, averaged fewer than 35 weeks of annual labor. To survive, entire families, including children, worked together in the fields and moved repeatedly to find as much employment as possible during the year. Housing, if provided at all by growers, frequently lacked heat, running water, and proper sanitation. Although the state established minimum standards for housing and sanitation, most farm labor camps were not inspected on a regular basis, and many growers simply ignored the regulations.

Farm workers also suffered from lack of health care. Even those who could afford medical services often had to travel long distances to the nearest clinic or hospital. As a consequence, they had significantly higher infant mortality rates and lower life expectancies than the general population. The 1962 Migrant Health Act, which provided federal funding for state and local health services, provided some relief, but failed to appropriate sufficient resources to meet even the basic needs of most farm workers. Education was yet another problem. Frequent moves interfered with regular school attendance and forced children to adjust to an ever-changing series of teachers, academic expectations, and learning environments. Rural schools, like those in the barrios, were typically segregated, overcrowded, and underfunded. Spanish-speaking students faced even greater difficulties. Not only was English the language of instruction, but students were often punished or ridiculed for speaking Spanish. Moreover, those who failed to keep up were frequently labeled as slow or retarded, and held back or placed on vocational tracks.

Community activists adopted a variety of strategies to address these problems. In urban areas, organizations like LULAC and the CSO attacked discrimination, lobbied for community improvements, and encouraged active political participation. Unlike LULAC, however, the CSO attempted to promote unity among Mexican Americans and immigrants by encouraging noncitizens to join and by helping newcomers obtain U.S. citizenship. Indeed, the CSO’s bylaws stated that “residents of the community who are not citizens of the United States shall be encouraged to become citizens and to actively participate in community programs and activities that are for the purpose of improving the general welfare.” As the CSO spread from Los Angeles to other cities across the state, its inclusive philosophy produced concrete results. By 1955, the organization operated more than 450 citizenship-training classes, which by 1960 had helped more than 40,000 immigrants obtain citizenship.

The Asociación Nacional Mexico-Americana (ANMA), formed in 1950, was even more determined to break down the barriers that divided immigrants and Mexican Americans. Like the CSO, ANMA emphasized citizenship and political participation; however, it also recognized that political and economic rights were interconnected. To counter economic exploitation, ANMA advocated unionization, building coalitions with other minority groups, and developing stronger connections with underpaid laborers in Mexico and Latin America. ANMA was also one of the earliest Mexican American organizationsto emphasize the beauty and richness of Mexican culture and vigorously attack negative stereotypes. In 1952, for example, it organized a national boycott against the Colgate-Palmolive-Peet Company, the sponsor of a radio show that contained offensive references to Mexican Americans. In Los Angeles, ANMA criticized Weber’s Bread Company for using unflattering caricatures in its advertising and mounted a similar campaign against Hollywood’s exploitation of popular stereotypes. Finally, ANMA, like the CSO, gave its support to the Los Angeles Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born (LACPFB), founded in 1950 to protest an increasingly aggressive federal immigration policy. ANMA was also an outspoken critic of police brutality against barrio residents.

By 1954, ANMA collapsed after its members and leadership were “identified” as Communists or Communist sympathizers by the FBI, and the U.S. attorney general branded it as a “subversive” organization; however, both ANMA and the CSO had succeeded in building electoral interest and activism among the state’s Spanish-speaking population. Just as significantly, both organizations helped foster a more positive sense of ethnic identity based on cultural pride and unity, rather than assimilation into the Anglo mainstream. The Mexican American Political Association (MAPA), founded in 1959, used this foundation to demand entry into the state’s Democratic Party structure. MAPA, which militantly promoted ethnic solidarity among Mexican Americans and de-emphasized cultural assimilation, devoted itself almost entirely to running candidates for office, voter registration drives, political lobbying, and get-out-the-vote campaigns.

Unlike ANMA, however, which weathered the postwar anti-Communist hysteria, neither MAPA nor the CSO spoke directly to the needs of the state’s farm workers. The National Farm Workers Labor Union, crippled by the bracero program and lack of funding, made little progress in organizing agricultural workers during the 1950s. Life in California’s fields remained one of sharp contrasts: between worker and employer, the poor and the wealthy, Mexicans and Anglos, the powerless and the powerful. At the CSO’s annual convention in 1962, Cesar Chavez, the organization’s national director, presented a plan to create a farm workers’ union and was voted down. Chavez, resigning from his post, returned to his farm worker roots in Delano and began to pursue his dream. In a few short years, his efforts would shake the nation’s conscience and inspire a new level of activism among the state’s Mexican Americans.

Asian Pacific Immigration and Activism

The postwar baby boom and somewhat more liberal immigration laws contributed to the growth of California’s Asian American population between 1950 and 1960. While new immigrants tended to cluster in older ethnic neighborhoods, established residents were more widely dispersed. This was particularly the case with Japanese Americans, whose prewar communities had often been appropriated by other ethnic groups during the war. The Japanese American population grew from 84,956 to 157,317 between 1950 and 1960, Chinese Americans from 58,324 to 95,600, and Filipinos from 40,424 to 65,459. The Korean population, while significantly smaller, almost quadrupled during the same period. Much of this increase grew out of U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War. Chinese immigrants, for example, benefited from the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, which granted entry to political refugees of the Communist Revolution. The Refugee Acts of 1953, 1957, and 1958, passed in the wake of the Korean conflict, extended asylum to both Chinese and Korean dissidents. The Walter McCarren Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1952, supported by Asian American organizations like the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), had an even greater impact. This act modestly expanded immigration quotas for Asian countries and granted the right of naturalization to Japanese, Chinese, and Korean immigrants. The law, by allowing aliens to apply for citizenship, also invalidated the California Alien Land Act, which had prohibited Asian noncitizens from owning property in the state. To remove any remaining ambiguity, California voters formally repealed the Alien Land Act in 1956.

The Walter McCarren Act, while dismantling many anti-Asian policies, contained some troubling provisions. It not only called for the detention and deportation of noncitizens suspected of “acts of espionage or sabotage” but also imposed tougher restrictions on illegal immigration. The postwar sweeps and raids of Mexican American barrios and the systematic deportation of outspoken community activists and union organizers were products of this act. Japanese Americans were particularly alarmed over the provision that authorized the creation of detention camps for suspected subversives and mounted a 20-year campaign to repeal that section of the law.

The postwar anti-Communist hysteria exerted a chilling influence on someAsian American political activity. On one hand, the government welcomed refugees from Communist countries. On the other, it mounted an aggressive attack against “subversives” from within. Citizens and noncitizens of Chinese and Korean ancestry were understandably reluctant to engage in political activity that might arouse suspicion of disloyalty. Japanese Americans, still traumatized by the ordeal of internment and struggling to reestablish their livelihoods, were also cautious, but less likely to be confused with the new Communist “enemy.” This small measure of immunity emboldened Nisei activists to lobby for Issei citizenship rights and the repeal of the McCarren Act’s detention clause.

As the anti-Communist hysteria tapered off in the late 1950s, there was a small but notable increase in Asian American political activism. The JACL joined forces with other civil rights groups to protest housing and employment discrimination and to lobby for equal rights legislation. At the same time, political organizations, including the Los Angeles–based West Jefferson Democratic Club, the Nisei Republican Assembly, and the Chinatown Democratic Club, and San Francisco’s Chinese Young Democrats and Nisei Voters League, claimed a role in local and state government. Nonpartisan civic organizations, which promoted mutual aid and community service, also expanded to meet the needs of a growing Asian population. The Chinese American Citizens Alliance, the American-Korean Civic Association, and the Filipino Community all helped to foster interest in civic affairs, maintain cultural traditions, and provide services to their respective ethnic groups.

Opportunities and Challenges for California Indians

For California’s Indian population, the postwar period brought both new opportunities and new challenges. Having made substantial contributions to the war effort on the battlefield and home front, Indians joined other minorities in securing their rights and seeking more equitable treatment. In 1944, after decades of lobbying and litigation, California Indians won an award of $5 million for the illegal seizure of tribal land. This award would have been greater if the federal government had not deducted funds that it had spent on reservation supplies and the administration of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in California. Indians immediately protested these deductions by filing suit against the federal government under the Jurisdictional Act of 1928. In response, the government established the Indian Land Claims Commission in 1946, a federal agency empowered to investigate and settle land claims. The following year, in 1947, Indians established a new organization, the Federated Tribes of California, to press the commission for a more just award than the 1944 ruling. Their efforts failed, and in 1951 the original settlement was distributed in per capita payments of $150 per Indian.

Indians, however, continued to file additional claims. Several claims seeking compensation for land west of the Sierra Nevadas were consolidated into a single case. In 1964, the Indian Land Claims Commission approved a settlement of $29,100,000 for 64,425,000 acres of lost territory in this region. After attorney fees were deducted, the award amounted to about 47 cents per acre, or $600 per eligible claimant. This settlement, like the one issued in 1951, left many Indians bitter and disillusioned.

In the middle of these contentious land claim disputes, the federalgovernment adopted a policy of termination that was designed to abolish government oversight and administration of reservations. In California, termination began in earnest with the 1958 California Ranchería Act. Under this act, the federal government identified 44 Indian rancherías as candidates for termination. In exchange for dividing up tribal landholdings among individual members, giving up their status as federally recognized tribes, and relinquishing all claim to all previously provided federal government services, tribes were promised various improvements to housing, schools, roads, sanitation systems, and water supplies. Over the next 12 years, 23 rancherías and reservations were terminated. As the policy was implemented, the federal government failed to provide the promised improvements to infrastructure. Many Indians, disgusted with poor living conditions or too impoverished to pay taxes on their individual allotments, sold their land. Those who remained often faced serious health threats from poor sanitation, contaminated water, and substandard housing. Finally, in some cases, tribal members did not receive allotments at all. As a result of these problems, most “terminated” tribes filed lawsuits against the government and won reinstatement as rancherías or reservations, but this process would take decades.

While termination was being implemented, the Bureau of Indian Affairs adopted a national program that had an indirect impact on California Indians. In 1951, the bureau instituted a voluntary relocation program designed to entice Indians off reservations and into urban areas with the promise of job training programs and other transitional services. This program drew nearly 100,000 non-California Indians—Sioux, Navajo, Chippewa, Apache, Mohawk, Shoshone—to Los Angeles and the Bay Area between 1952 and 1968. Many Indians who made the move arrived without the education, work experience,or life skills to survive in an urban environment. Although they received help finding employment, the federal government provided few other support services. Widely dispersed and far from home, these newcomers faced isolation, loneliness, and alienation.

In time, however, California Indians and these newcomers came together to establish new organizations that addressed their common concerns. In 1961, with the help of the American Friends Service Committee, Indians of both groups established the Intertribal Friendship House in Oakland. The following year, Friendship House activists formed the United Bay Area Council of American Indians. In Los Angeles, in 1958, urban California Indians and newcomers founded the Federated Indian Tribes to promote social events and preserve traditional customs and values. These and other organizations provided a foundation for the increased intertribal activism of the late 1960s and 1970s.

Student Activism

During the prosperous postwar period, attending college became the norm for middle-class youth. And a college education, although narrowly conceived by campus administrators as training a new generation of technicians and managers, introduced students to a broad spectrum of issues and problems outside of the comfortable confines of suburban communities. Students’ very affluence, far from reinforcing the economic or political status quo, provided the freedom to reflect critically on social values and institutions, and ponder their responsibility to “make a difference” in the world. Raised to believe that capitalism and democracy had created a society free of the poverty, inequality, and political repression that plagued other nations, students soon discovered another, deeply flawed America. This awakening, rather than producing cynicism and despair, gave students a sense of purpose. As the “best and the brightest,” they could be instruments of social transformation, forcing America to live up to its values.

Student dissent began in 1957 on the Berkeley campus, when a small group of activists formed an organization called SLATE. Its members, impatient with the trivial issues that had long dominated student politics, campaigned against compulsory participation in ROTC and against racial discrimination in sororities, fraternities, and other campus organizations. They also pressed for the creation of a cooperative bookstore and a stronger university policy against housing discrimination within the city of Berkeley. While expanding their influence in student government, SLATE members became increasingly active in the surrounding community. In 1959, the group planned an on-campus rally in support of a citywide fair housing initiative sponsored by a local socialist organization. University administrators, invoking a regulation that prohibited campus groups from supporting outside political causes, ordered SLATE to cancel its demonstration. SLATE refused, and more than 300 students attended the rally.

In 1960, SLATE moved beyond the Berkeley community to organize a protest against the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings in San Francisco. Incensed over HUAC’s violation of civil liberties in the “defense” of democracy, students were determined to voice their opposition to its hypocrisy. On Thursday, May 12, Berkeley protestors, joined by San Francisco State College students and faculty, gathered for a rally and picket at Union Square, and then marched to city hall to observe the hearings. Once there, however, students were denied entry passes. On Friday, hundreds of other students joined the original contingent in demanding admission to the proceedings. Barred again from the hearing room, the protestors staged a peaceful sit-in at city hall. As they sang “We Shall Not Be Moved,” armed police officers forcibly rejected them from the building with clubs and high-powered water hoses. Demonstrators and bystanders alike were shocked by the violence of the police response, watching in horror as the “best and the brightest” were “dragged by their hair, dragged by their arms and legs down the stairs so that their heads were bouncing off the stairs.” This show of force, however, only strengthened the students’ resolve. The next day, 5000 protestors gathered at city hall to picket the hearings.

Although SLATE was prohibited from using university facilities and denied on-campus status following the HUAC demonstrations, activism continued to

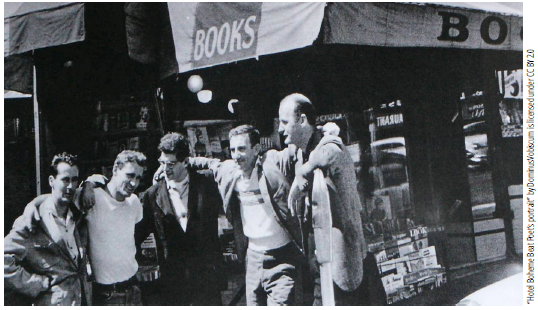

Bob Donlin, Neal Cassidy, Allen Ginsberg, Robert La Vinge, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti (left to right) outside of Ferlinghetti's City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco. Contrast this image with popular depictions of American life during the 1950s. Does anything in the photograph suggest that its subjects are part of a rebellion against conventional norms and values?

flower on the Berkeley campus. By 1963, students would find yet another cause to champion—the national and local struggle for civil rights.

Cultural Developments

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, the San Francisco Bay area provided a haven for radical writers, artists, playwrights, and actors, many of whom had spent the war in prison or in Civilian Public Service camps for refusing military service. Some, influenced by Gandhian nonviolent philosophy, believed that there were moral alternatives to war. Others, influenced by socialist or anarchist beliefs, saw World War II as a struggle between expansionist nations for global dominance—a struggle that imposed suffering on millions of innocent civilians in the service of corporate and state interests. Their views, highly unpopular during the “Good War,” met with equal hostility in the Cold War period. By creating an intellectual community in San Francisco, however, they not only escaped isolation and ostracism but also produced a literary and artistic renaissance that stood in stark contrast to the generally barren cultural landscape of the 1950s.

The poets and writers of the San Francisco Renaissance, including William Everson and Kenneth Rexroth, broke new literary ground through their conscious “repudiation of received forms” of composition and their pointed critiques of militarism, consumer culture, corporate greed, government corruption, and social conformity. Renaissance actors and playwrights, lacking a venue to perform works that “were significant and avant-avant-garde,” established the Interplayers, one of San Francisco’s first repertory theaters. Others, like Roy Kepler and the poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, opened bookstores that sold controversial literature, hosted poetry readings, and served as social centers for artists and writers. KPFA, the nation’s first listener-supported radio station, also emerged out of this cultural ferment, creating an opening on the airwaves for radical, dissenting voices.

By the mid-1950s, this flourishing subculture helped nourish a new literary and artistic movement. In October 1955, San Francisco’s Six Gallery hosted a poetry reading that attracted about 150 participants, including the novelist Jack Kerouac and a young, aspiring poet named Allen Ginsberg. Ginsberg’s poem entitled “Howl” attacked the spiritual and emotional sterility of postwar culture and captured the longing of American youth for more than the “ample rewards” of conforming to “the conventions of the contemporary business society.”

The critical edge in “Howl” was made even sharper by its strong language and generated a backlash that propelled the “Beat” poets into the national spotlight. In 1956, Lawrence Ferlinghetti published Howl and Other Poems out of City Lights, his North Beach bookstore. The police, charging that the volume was “obscene and indecent,” confiscated copies of the book. Ferlinghetti fought back in court, obtaining a much publicized and positive verdict that “Howl” was literature, not pornography. Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, which celebrated the intentional rejection of the work ethic, material success, emotional reserve, and sexual inhibition, was published in the wake of the “Howl” publicity, and added further stimulus to the movement. By the late 1950s, the Bay Area became a mecca for new writers, including Denise Levertov, Philip Whalen, Gary Snyder, Peter Orlovsky, and Ken Kesey. Artists, including Jay “The Rose” DeFeo and Joan Brown,boldly experimented with color, texture, and new materials, adding to this rich cultural environment.

Alan Watts, a scholar and practitioner of Zen Buddhism, influenced this new literary subculture by introducing Beat writers to Eastern religious traditions that emphasized harmony with nature, renunciation of material possessions, voluntary simplicity, pacifism, and faith in internal rather than external sources of authority. By exalting these values, Beat writers moved beyond mere criticism to create an alternative vision of society that sparked the idealism of young Americans and confirmed their faith that they could make a difference in the world. Just as significantly, the Beats’ philosophical orientation helped inform the much broader countercultural movement of the 1960s.

After the war, southern California became a cultural center of national, even international, importance. This transformation began in the 1940s, as hundreds of European refugees, including prominent writers, actors, artists, art collectors, and musicians, found a safe haven in the Los Angeles area. Previously recognized for its Hollywood productions, Los Angeles emerged as a serious contender in theater, symphony, and classical and modern art. Across the state, popular culture also flourished. Country music, brought to California by white migrants during the Depression and war years, established Bakersfield as the “Nashville of the West” by the early 1960s. Similarly, black migrants transplanted and later adapted their blues tradition, creating a distinct “California” style of playing. In the suburbs of Los Angeles, the Beach Boys put a southland spin on rock music. Their “California sound,” celebrating surf, beaches, sunshine, and young love, introduced the nation’s youth to the “California Dream.” Finally, Disneyland, McDonald’s, and Hollywood’s new television industry changed family recreation patterns and placed southern California at the forefront of consumer culture.