1.20: Conducting Peer Review

- Page ID

- 143688

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Peer review, or peer editing, is the process in which you and your peers exchange documents and provide feedback on those documents for what the author executed well in the paper and also how the author can improve the document.

Benefits of Peer Review

Peer review provides several benefits for you as a student, including:

- Seeing how peers draft their documents and seeing that there is not only one right way to go about drafting

- Being placed in the role of the reader to see how organization and style affect the readability of the document

- Learning to work with others on both providing and receiving meaningful and respectful feedback

- Practicing providing effective feedback that provides solutions to the peer

- Taking in feedback from peers, including evaluating whether to implement the feedback received

- Engaging in a type of feedback that is different from, but no less valuable than, receiving written feedback from a professor

- Transferring the process of providing peers feedback to providing yourself feedback

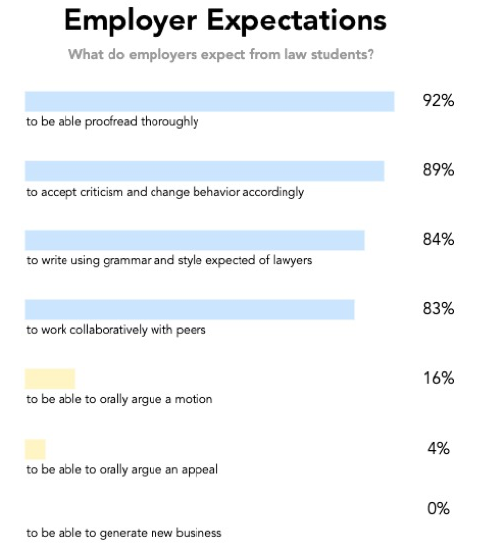

Employers also expect that you will have mastered several of these skills as you enter internships. Alexa Chew and Katie Rose Guest Pryal, Bridging the Gap between Law School and Law Practice (January 1, 2015), Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2575185, surveyed legal employers about nineteen types of skills that employers expected law students to have when they entered the office setting. Employers’ responses, reported as percentage who agreed with students having a particular skill, showed they expected law students to be able proofread thoroughly (92%), accept criticism and change behavior accordingly (89%), write using grammar and style expected of lawyers (84%), and work collaboratively with peers (83%). Id. at 7. Conversely, at the bottom of the list were being able to orally argue a motion (16%), being able to orally argue an appeal (4%), and being able to generate new business (0%). Id. at 8.

How to Conduct Peer Review

When conducting a peer review, remember that you are not a copy-editor, a close friend, or a competitor. Rather, you are expected to act as a neutral observer who is trained in legal writing and who is providing specific and practical ideas on what works and what needs more development within the document.

We will use a modified version of the peer review model from Alexa Z. Chew and Katie Rose Guest Pryal, The Complete Legal Writer, 409-12 (2016), that calls for the peer editor to read through the document three times. The editor looks for specified items during each read-through and reserves judgment until the final read-through.

First Read-Through: React and Notate

In the first read-through, you will be reacting to the words on the paper. Ask yourself: What is easy to follow or hard to follow? What parts flow smoothly and what parts cause you to stumble or stop when reading? At this point, do not write any lengthy comments on the paper. You should, however, make notations on the page.

Peer Review Reader Reaction Notations

!! Passages with which you agree strongly

? Passages that don’t seem to connect with paper

✓ Passages that are particularly effective

w/c When a word does not fit

awk When a sentence or phrase does not read smoothly

You can choose to use other types of notations, but you should be sure to provide a key for your author to interpret your notations. The purpose of this first read-through is to interact with the paper for the first time, observe how the language and organization strikes you, and then to provide quick feedback.

Second Read-Through: Reverse Outline

In the second read-through, you should create a reverse outline of the author’s work in the margins. A reverse outline is the product of the process of taking a finished piece of writing and showing the author how the reader sees the organization of the document. For instance, if you are reading an analytical section of a memo, locate the conclusion, the rule, the explanation, the application, and the wrap-up conclusion (CREAC). However, if you are reading a letter, then you would label the address, the salutation, the introductory piece, each body paragraph’s main point, the closing, and the signature line. As you do this second read-through, you might see missing parts that are necessary for the document to be complete. Do not yet try to correct what is missing. You are still reacting to and observing how the document has been put together.

Third Read-Through: Problem-Solve

In your third read-through, you should finally explain why you had the reactions and observations that you did in the first and second read-throughs. Why did you have to read certain passages multiple times? Do not just tell the author that you had difficulty reading the passage. Provide a solution to the issue. Were the sentences too long? Were there typos that distracted? Was the content confusing, and if so, in what way? Do the same thing to discuss what surprised you about certain passages and what made certain passages particularly effective.

Optional Read-Through: Proofreading

This optional read-through is what most people initially think peer review involves: you correct typos, punctuation issues, spacing mishaps, and grammatical errors. While this type of feedback in beneficial, a proofreading re-through is best for when the substantive content is complete and the writer is prepared to submit the written document. Correcting comma placement is not helpful if the writer really needs to focus on shoring up their explanation about why a particular point of law should be interpreted in the way in which they argue it should be.

If you are reviewing a peer’s work online, you should still use this same three read-through method. Use the feature in your word processor such as “track changes” in Microsoft Word or “add comment” in Google Docs to make the notations recommended in the first read-through. You can use that same feature for your second read-through, or you can color-code each section. Be sure to include a key indicating what each color means to which the writer can refer. For the third read-through, you can put your comments at the end of the reviewed document, in a separate document that you share, or in the body of an email when you return the document with your annotations from the first and second read-throughs.

As you finalize your feedback, make sure you have shared with the author what worked, what did not, and how to fix what did not work. When giving feedback, you should recognize the strengths of the document and not just point out its weaknesses. You can always find a strong point in any document, and when you are providing feedback it is essential that you discuss what went well in a paper.

Keep in mind that the purpose of engaging in peer review is not to cut the author down or to prove your superiority. Rather, peer review is a cooperative learning exercise that allows both you and your peers to learn how to write and how to edit. Approaching this exercise with the proper mindset is essential to allow each participant to benefit.

When deciding how to give feedback, plan to tell the author: 1) what worked well; 2) where and how the writing went wrong; and 3) how to solve the issues presented. To be effective at peer review, it is essential that you provide solutions or recommendations on how to resolve weaknesses in the document. Merely pointing out mistakes and issues will not help the writer nearly as much to improve the quality of their subsequent drafts.