1.1: Sources of Law and Court Systems

- Page ID

- 143669

This chapter covers where our laws come from and how different types of laws have varying weights of importance. A large part of law school, and being a lawyer, is figuring out if there is a law that applies to a specific situation to tell us what the outcome in that situation should be. Before looking for laws that sound like they apply, however, you need to know in which sets of laws you should start looking.

One of the primary tenets of the American legal system is (supposed to be) that you can predict what the outcome will be in a given situation because you can look to past cases with similar facts and know that the same types of reasoning in those past cases will be used in the current situation.

Different Ways to Sort Legal Material

Mandatory Authority Versus Persuasive Authority

Mandatory authority refers to any law that a court in a particular jurisdiction must follow when trying to solve a legal problem. This will include the United States Constitution, the state Constitution, judicial decisions by the United States Supreme Court, judicial decisions made by higher courts in that court’s jurisdiction, statutes enacted by the legislature, and regulations promulgated by administrative agencies that exercise authority over that jurisdiction. Most often in law school, you will be applying cases and statutes to hypothetical situations, so throughout this manual I will focus on those two types of law.

Persuasive authority, then, refers to any law or other material that a court may consider when trying to solve a legal problem. There are times when a particular jurisdiction does not have any statutes, cases, or other laws that address the legal issue, so a court can look outside its own jurisdiction for guidance about how to proceed. Other times, a jurisdiction considering changing its law will look to other jurisdictions to see how they are currently addressing a particular issue. Persuasive authority includes all laws and

material from any place outside the jurisdiction, including state Constitutions, judicial opinions, statutes, and regulations.

Precedent and Stare Decisis

The United States follows the English common law system, which means, in very simplified terms, that judges create laws as they render decisions, and that future individuals and entities are bound by those decisions in the same way they would be if that law had been enacted as a statute. Several of your first-year courses come from this common law system, although the principles in some jurisdictions have been codified.

Legal precedent means past judicial decisions that a court must follow in the future; therefore, legal precedent is a type of mandatory authority. To determine whether the past case must be followed, the court and the parties will consider if (a) the material facts of the past case and the current situation are the same, and (b) the legal reasoning applied in the past case is applicable to the current situation. To preview what we will be learning about in later chapters and throughout this year, these are two of the most important skills that you will need to learn: how to determine material facts and how to apply legal reasoning to those material facts.

Stare decisis is Latin for “let the decision stand.” When there has been a decision on a past set of facts that is just like the set of facts currently before the court, then the court must hold that the same outcome should occur. Based on the description of precedent and stare decisis, it can feel like there is not a lot of room for people to disagree on whether a past case will apply. Either it does or it does not, right? Not so fast.

Courts, lawyers, and other participants in the legal system all have options in how they view material facts and legal reasoning. We can interpret a case to have a narrow holding, meaning that it only applies in a few specific situations, or we can interpret that same case to have a broad holding, meaning that it applies in lots of situations.

The primary tools you will use to decide whether a case applies to a current legal issue are analogy and distinction. While much of law school is spent using these tools, we will only briefly touch on them in this chapter. To analogize a past case to a current legal issue means to find the ways in which that case is similar to what is happening now. On the other hand, to distinguish a case means to find the ways in which that case is different from what is happening now. Once you analogize or distinguish the past cases, you can then argue that the court should rule a particular way based on your interpretation of how to apply those past cases in the current legal situation.

Primary Sources versus Secondary Sources

The sources of law that we have been discussing (Constitutions, statutes, regulations, cases) are all considered primary authority. To be considered primary authority, the material must be a type of law itself. However, there are also many materials that interpret, explain, and discuss laws, and these are called secondary authority. Examples of secondary authorities are American Law Reports (ALR), Restatements, encyclopedias, treatises, hornbooks, legal digests, textbooks, legal periodicals, and law review articles.

To use an analogy to explain, think about being in history class and studying the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration of Independence, in its cursive handwriting on yellowed parchment, is a primary source. Any reproductions of the specific words in the text would also be considered a primary source. If you want to find out how the words of the Declaration of Independence were used to influence the French Revolution, you could find a book in the library or a resource online that would discuss the Declaration of Independence and explains its influence on the French Revolution. That book is a secondary authority. It takes the words of the primary source and manipulates them to present an argument about a particular point of view.

In the same way that a book examining the Declaration of Independence is a secondary authority, materials that examine sources of law are types of secondary authority. These types of authority are excellent for starting your legal research and for gaining a foundational understanding because they provide an overview of the particular topic and are often presented in easier-to-understand terms than what you will find in cases. Your legal research professor will spend time showing you many resources that you can use.

However, it is important to always keep in mind that, no matter how recognized or brilliant a secondary authority is, you should only rely on it as persuasive authority to a court. Remember, secondary authority is not law, but only one person’s interpretation of a law.

There are times when a court will adopt a secondary authority’s point of view and make it into the law of that jurisdiction. At that point, however, mandatory authority is the case that adopted the language, and not the secondary authority. For example, take the Restatement Second of Torts. A Restatement is a secondary authority. However, if a Michigan court in the Michigan case Fowler v. Wells decides to adopt the definition of contributory negligence in the Restatement, then the definition that was in the Restatement is now the definition applied in Michigan. However, if in a future legal situation you wanted to rely on that contributory negligence definition, you would cite to Fowler v. Wells, not the Restatement.

How Much Weight to Give Different Legal Material

We have looked at different ways to sort legal material: mandatory versus persuasive, whether it’s precedent or stare decisis, and primary versus secondary. Having ways to sort these things is all fine and well, but how does this actually play out when you are a lawyer writing to a court or a law student writing a legal document for a class?

Different types of authority have different weight depending on what the legal issue is and in what jurisdiction the legal issue has been brought. Mandatory authority in a particular jurisdiction is given more weight than persuasive authority. Precedent is given greater weight, and stare decisis is given greatest weight of all.

Primary authority in a particular jurisdiction is given more weight than secondary authority.

The primary authority, whether it be the Constitution, a statute, a regulation, or a case, must be relevant to the legal issue that is being considered. If the law does not have a connection to the legal issue at hand, then it has no weight at all.

Sources of Law: Federal System and State System

The United States has three branches of government: the Executive branch, the Legislative branch, and the Judicial branch. Each state within the United States also has a similar governmental setup. All three branches make laws; we often only think about law as being that handed down by judges, but there are far more sources of law than just cases.

Sources of Law

- Constitution

- Executive Branch

a. Executive orders

b. Administrative rules and regulations - Legislative Branch

a. Statutes

b. Codes

c. Ordinances - Judicial Branch

a. Case law/judge-made law

b. Procedural rules

Not only do we have to keep track of different types of authority and multiple sources of law, we also have to remember the dual tracks of federal and state law. A legal issue that is rooted in federal law will rank weight of authorities differently than a legal issue that stems from state law.

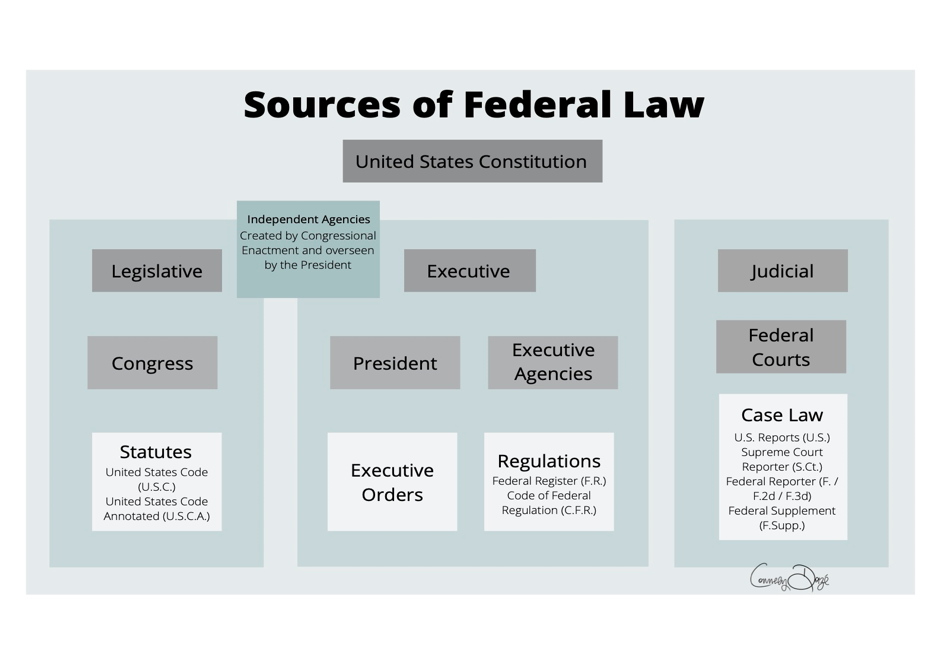

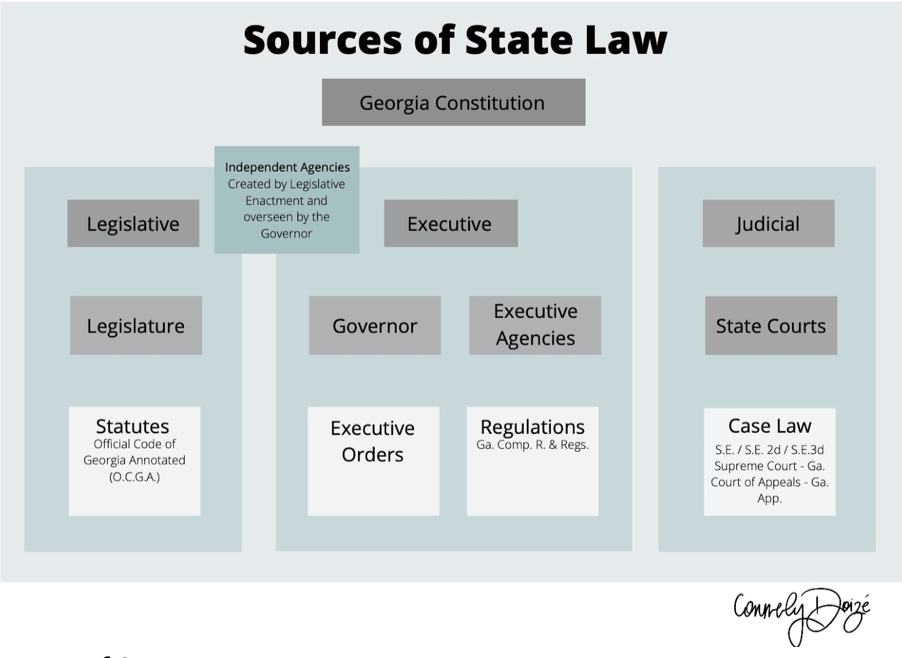

The first two graphics and outlines below show from which branch different types of law are created and also provide information on what resource you can consult to locate that type of law. The first graphic and outline show sources of federal law. The second graphic and outline show sources of Georgia state law. Keep in mind that each state, commonwealth, and territory will have its own structure. No one structure is in use and you will have to check on the structure and system in place in the particular jurisdiction in which you are researching, writing, or working.

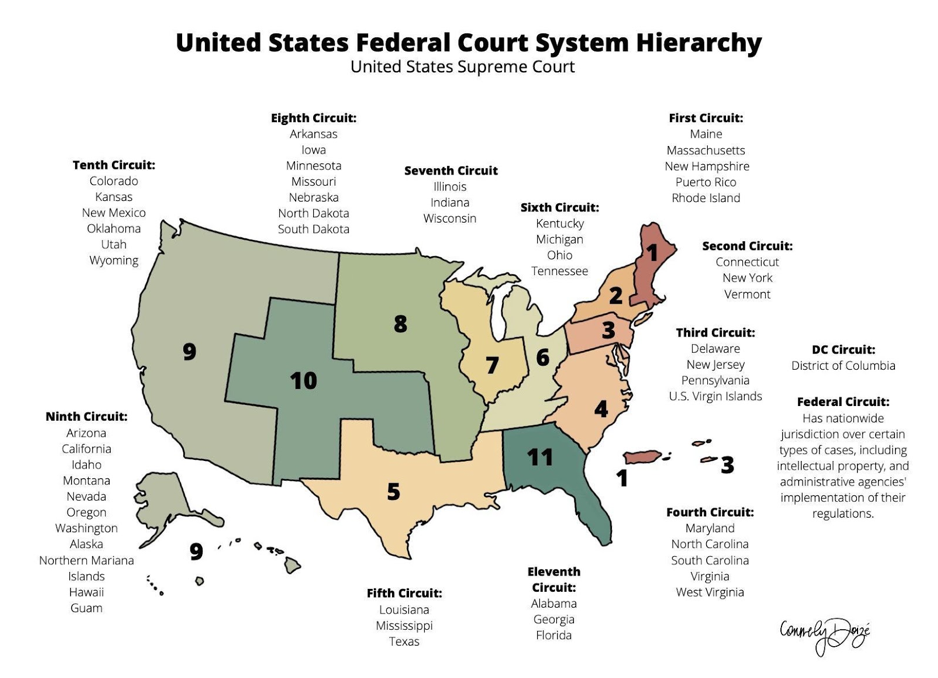

The third graphic and outline show the United States federal court hierarchy as an example of how different courts’ opinions should be weighted. A highest court’s judicial opinion will carry more weight than an intermediate appellate court, and a lower court’s opinion will carry the least weight of all.

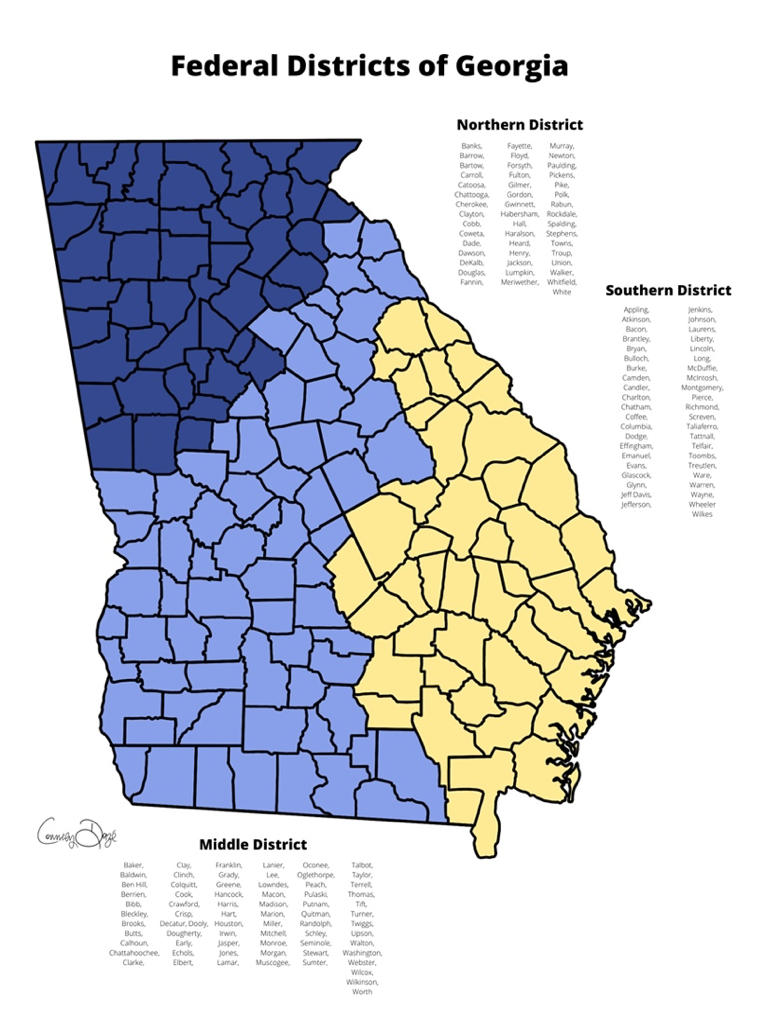

The fourth graphic shows how Georgia’s counties are divided into three federal districts. The fifth graphic shows the hierarchy of courts in Georgia. Again, a highest court’s judicial opinion will carry more weight than an intermediate appellate court, and a lower court’s opinion will carry the least weight of all.

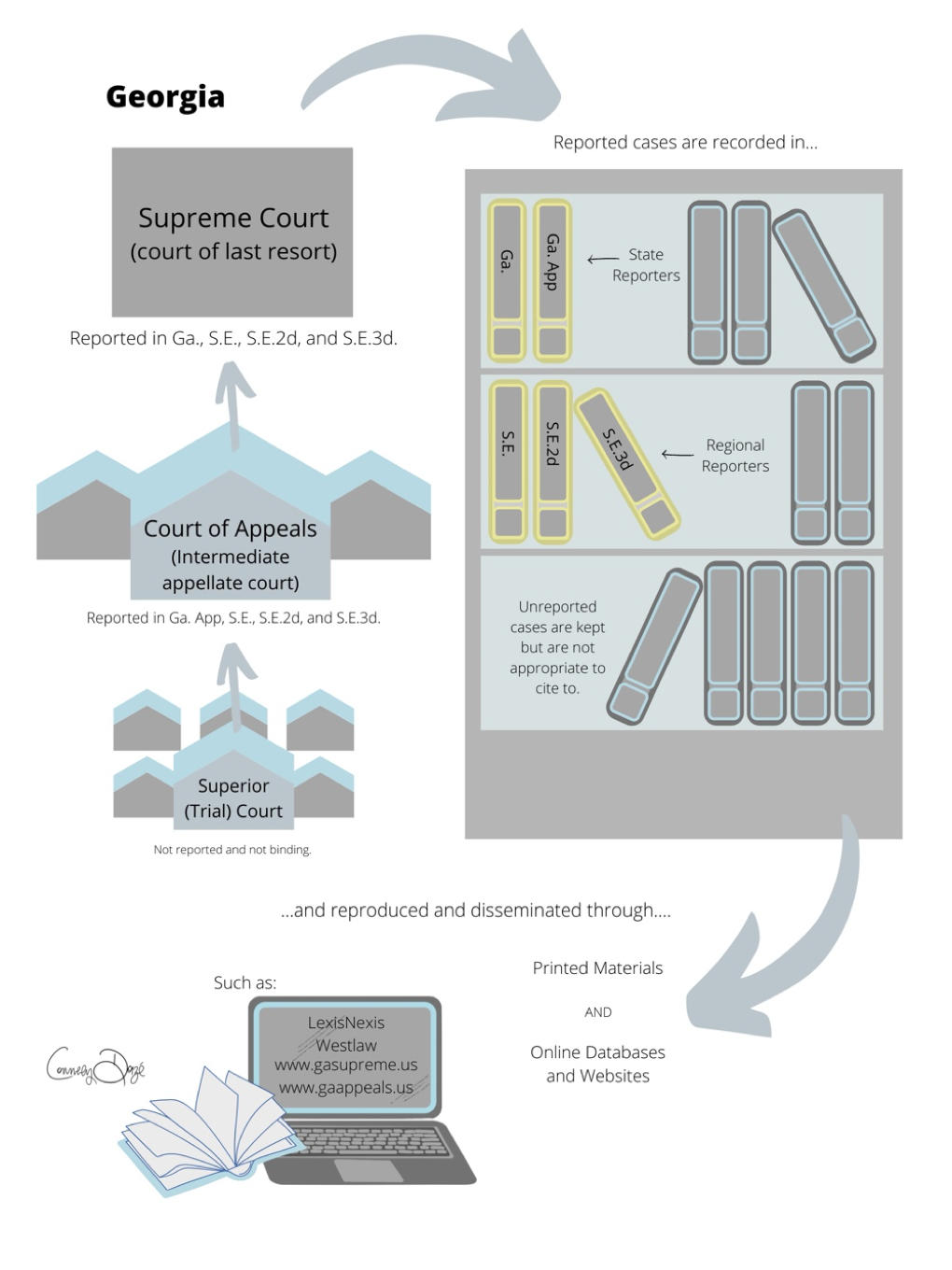

The sixth graphic summarizes how cases move from Georgia trial courts through the appellate courts, with the opinions issued by the appellate courts becoming law that you can research in either print or online databases.

Sources of Federal Law

- United States Constitution is the highest source of federal law

- Legislative Branch

- Congress enacts statutes that are recorded in

- United States Code (U.S.C.)

- United States Code Annotated (U.S.C.A.)

- Congress enacts statutes that are recorded in

- Independent Agencies: Created by Congressional Enactment and overseen by the President, so they straddle the Legislative and Executive Branches

- Executive Branch

- President issues Executive Orders

- Executive Agencies issue Regulations that are recorded in

- Federal Register (F.R.)

- Code of Federal Regulation (C.F.R.)

- Judicial Branch

- Federal Courts make case law decisions that are written in

- U.S. Reports (U.S.)

- Supreme Court Reporter (S. Ct.)

- Federal Reporter (F. / F.2d / F.3d)

- Federal Supplement (F.Supp.)

- Federal Courts make case law decisions that are written in

Sources of State Law

- Georgia Constitution is the highest source of Georgia state law

- Legislative Branch

- Legislature enacts statutes that are recorded in the Official Code of Georgia Annotated (O.C.G.A.).

- Independent Agencies: Created by Legislative Enactment and overseen by the Governor, so they straddle the Legislative and Executive Branches.

- Executive Branch

- Governor issues Executive Orders

- Executive Agencies issue Regulations that are written in Ga. Comp. R. & Regs.

- Judicial Branch

- State Courts make case law decisions that are recorded in

- S.E. / S.E. 2d / S.E. 3d

- Supreme Court of Georgia- Ga.

- Court of Appeals of Georgia- Ga. App.

- State Courts make case law decisions that are recorded in

United States Federal Court System Hierarchy

- The United States Supreme Court is the highest Court.

- There are thirteen Circuit Courts in the United States.

- First Circuit: Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Puerto Rico, Rhode Island.

- Second Circuit: Connecticut, New York, Vermont.

- Third Circuit: Delaware, New Jersey Pennsylvania, U.S. Virgin Islands.

- Fourth Circuit: Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia.

- Fifth Circuit: Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas.

- Sixth Circuit: Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, Tennessee.

- Seventh Circuit: Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin.

- Eighth Circuit: Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota.

- Ninth Circuit: Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, Northern Mariana Islands, Hawaii, Guam.

- Tenth Circuit: Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah, Wyoming.

- Eleventh Circuit: Alabama, Georgia, Florida.

- D.C. Circuit: District of Columbia.

- Federal Circuit: Has nationwide jurisdiction over certain types of cases, including intellectual property, and administrative agencies’ implementation of their regulations.

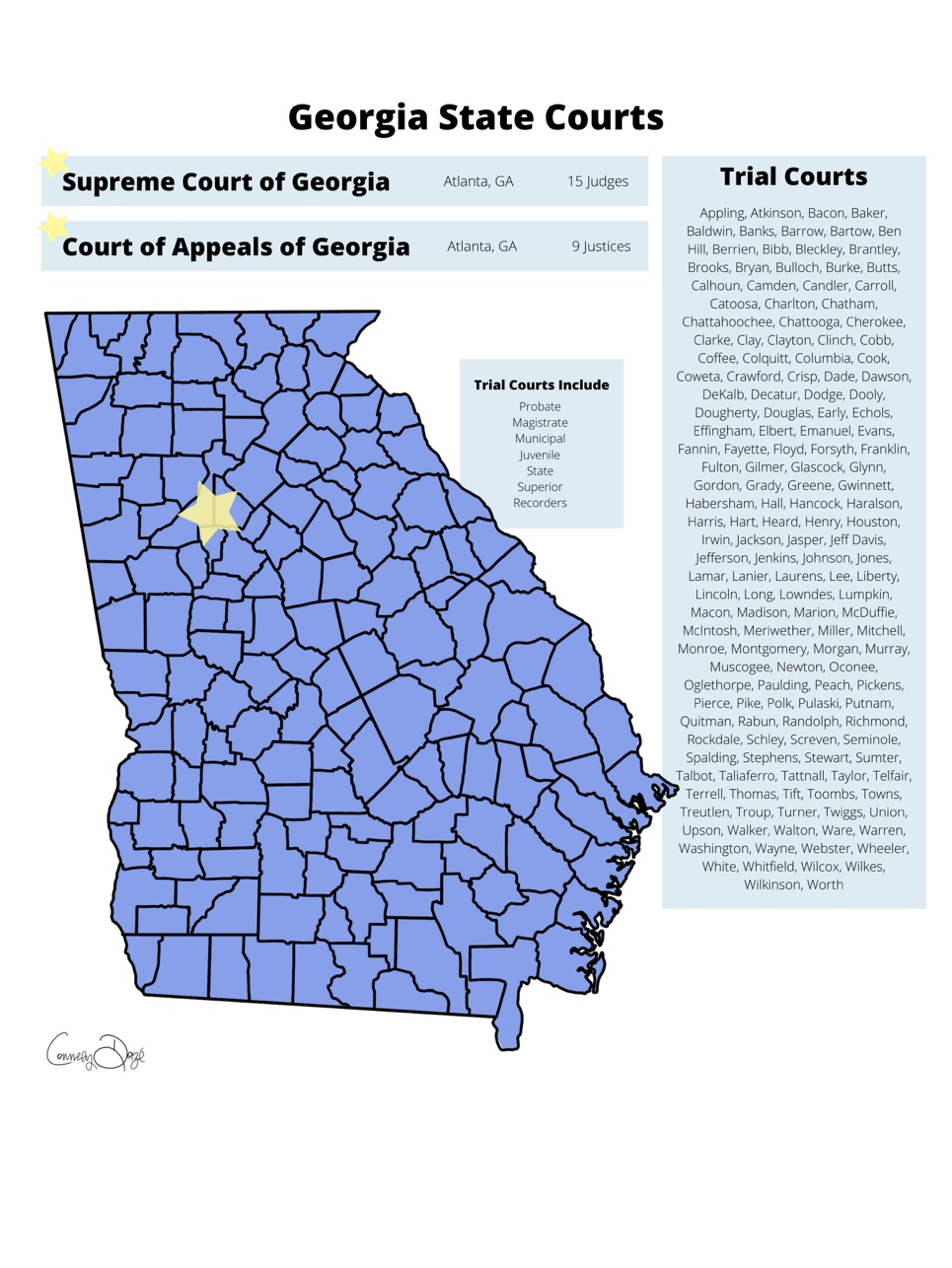

Georgia State Courts

- There are 159 counties in Georgia and each has its own trial-level courts, which includes a Superior Court, a Probate Court, a Magistrate Court, and a Juvenile Court. Other trial-level courts include Municipal, Juvenile, State, and Recorders Courts.

- Generally, appeals from county Superior Courts go to the Court of Appeals of Georgia, which is located in Atlanta, Georgia. There are certain types of cases, including but not limited to Constitutional issues, habeas corpus cases, and any case where a sentence of death could be imposed, that go directly to the Supreme Court of Georgia.

- The Supreme Court of Georgia is the court of last resort in Georgia and is also located in Atlanta, Georgia. In addition to cases over which the Supreme Court has exclusive appellate jurisdiction, including the types of cases named above, all appeals from the Court of Appeals of Georgia can be heard by the Supreme Court of Georgia if the Supreme Court grants the petition for a writ of certiorari to hear the case.

Conclusion

This chapter has given you a quick overview of where our laws come from and how we decide what type of legal material to rely on when formulating legal positions. Like with the material in the rest of the chapters in this manual, there is always more than can be learned and nuances that are not covered.

For Further Reading

Thomas O’Malley, Sources of Law; An Introduction To Legal Research And Writing 119-130 (1993).

Linda Edwards, Practical Case Analysis 2-4 (1st ed. 1996).

Steven M Barkan, Barbara A. Bintliff, Mary Whisner, Legal Research Illustrated, 1-9 (10th ed. 2015).

Tina M. Brooks & Beau Steenken, Sources of American Law: An Introduction to Legal Research (4th ed 2019).

David Romantz & Kathleen Elliot Vinson, Legal Analysis 3-18 (1st ed. 1998).

Nancy Schultz & Louis J. Sirico, Legal Writing and Other Lawyering Skills 9-21 (3d ed. 1998).