1.5: Time Management

- Page ID

- 143673

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)One of the challenges that many law students encounter during law school is how to effectively manage their time. Many of you were high achievers at your undergraduate institutions. Some of you have also worked full-time jobs prior to entering law school and were successful in those endeavors as well. However, first-year law students often find that the techniques on which they relied previously to complete their studies are no longer sufficient. This chapter serves to offer some advice, tips, and tools to consider.

ABA Standard 310

To be accredited by the American Bar Association, law schools must comply with a series of standards that the ABA imposes. These standards are meant to ensure that students receive quality legal educations at their institutions and that their education will be beneficial for the law students’ eventual transitions into legal practice.

One of the primary standards that directly impacts you as a law student from the first day of law school is ABA Standard 310, which requires law students to spend a certain amount of time working in and out of class for each credit hour earned. American Bar Association, ABA Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools 22 (2020).

The impact is that for every hour you spend in class, you should expect to spend at least two hours outside of class doing work for that class. At the University of Georgia School of Law, incoming first-year students currently take 16 hours in their fall semester. Doing the math, that means that in your fall semester, your courses are intentionally designed so that you should be spending 16 hours in class each week and at least 32 hours doing work outside of class each week. These 48 hours a week of work between attending classes, reading for classes, outlining for exams, and writing papers. This 48 hours a week does not take into account the time you need to eat healthy meals, exercise, maintain connections with your friends and family, and continue pursuing the hobbies that you currently enjoy. And yes, you should still find time to do all of these things.

Stay with me! You can do this! Every year most law students adapt to this new type of schedule and are able to be successful. The sooner you start adapting, however, the better off you will be. Your time is valuable, and how you use it matters. There are two components to effective time management that we will discuss: your weekly schedule and how you use the time during each block.

Weekly Schedule

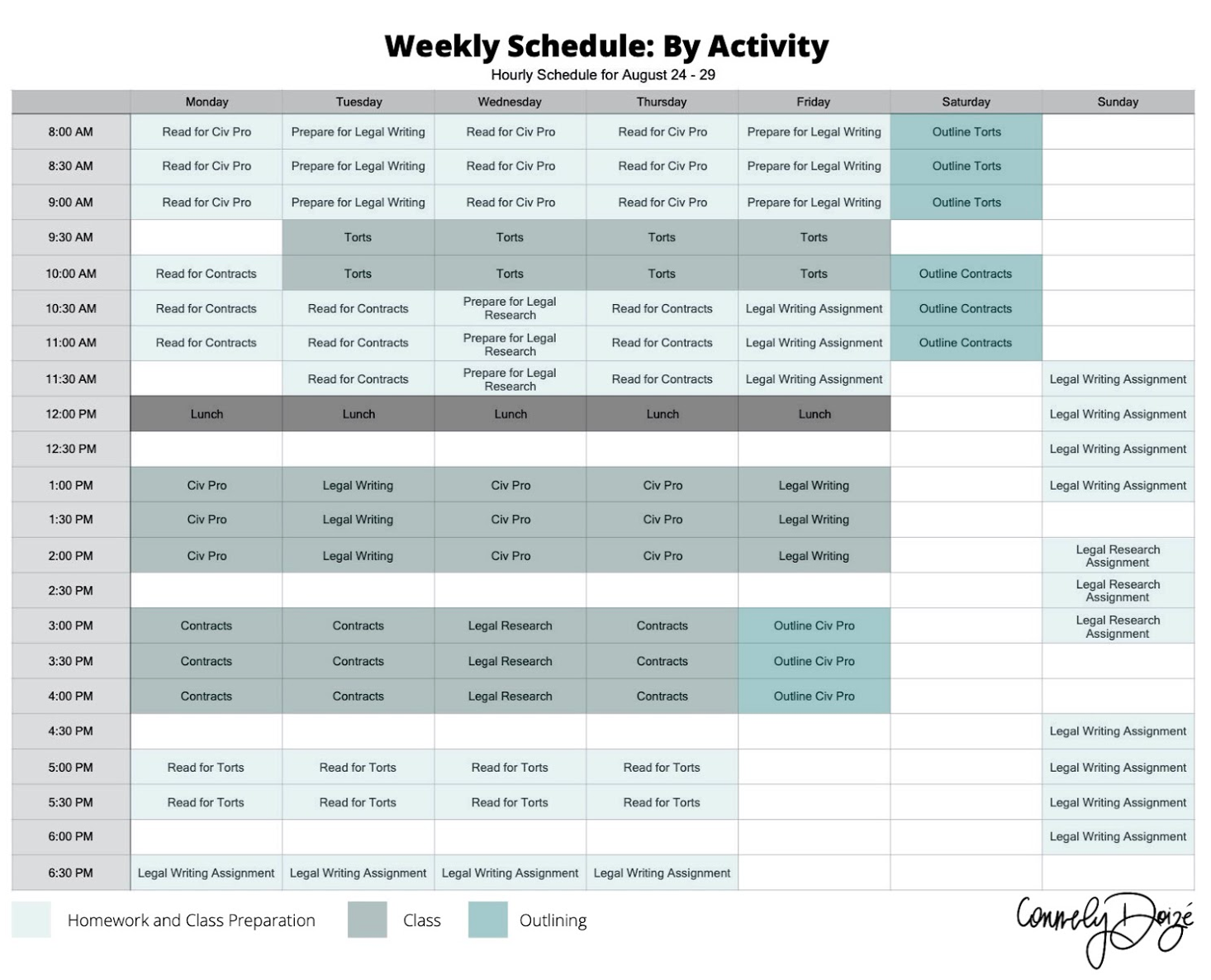

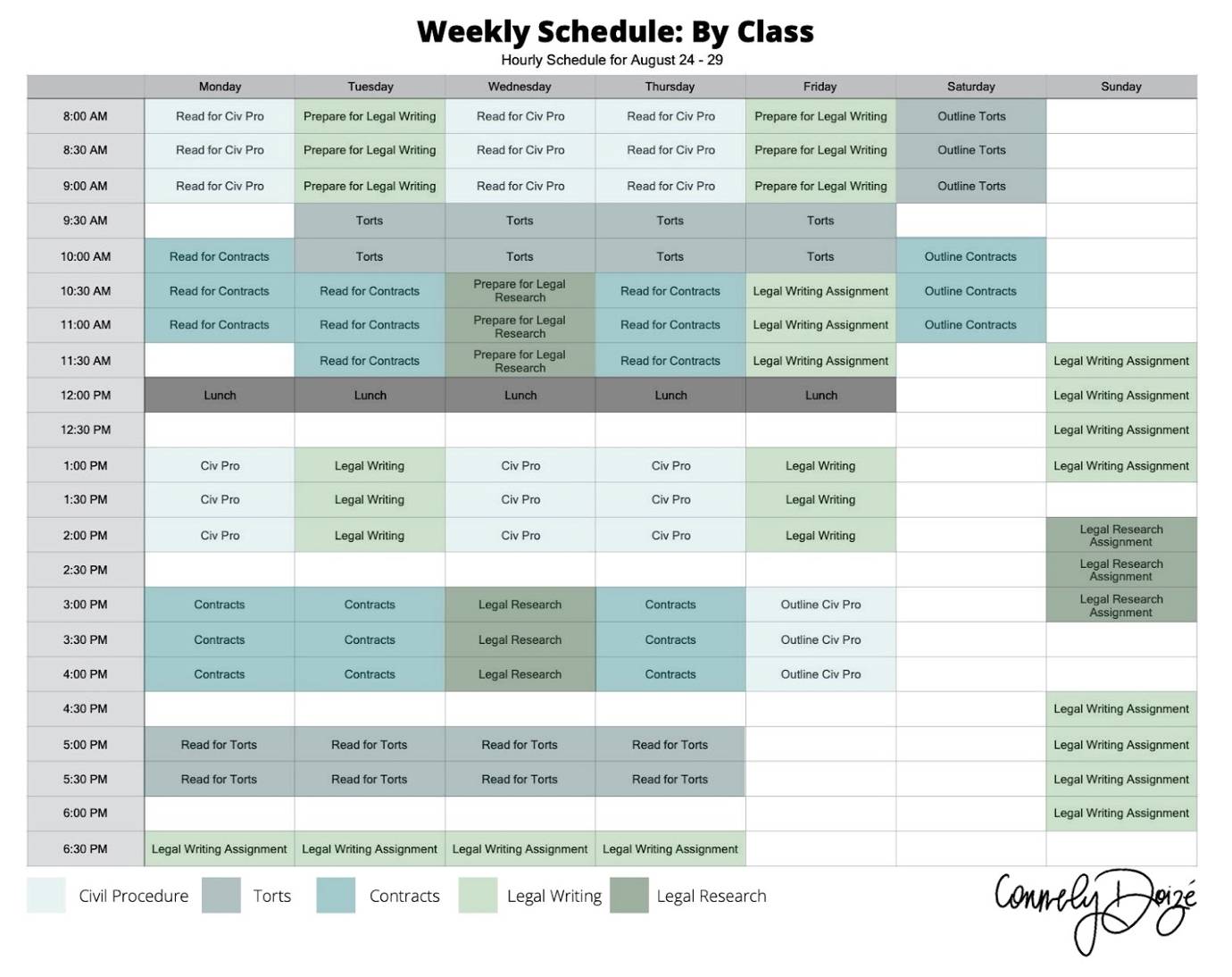

First, you need to decide how you want to keep track of your organized time. Some people like to use calendars that are connected to their email accounts. Others like to use fancy paper planners (I’m one of those people). Still other folks use online task-management services like KanbanFlow or Trello. Heck, some people just find a blank sheet of paper and scribble on it. Two sample weekly schedules are included at the end of this chapter. Whatever method will consistently work for you is what you should use.

When selecting your type of planner, you should consider what method you will be most likely to regularly use and that will not be so time-consuming to maintain that you give up. Using a color-coded, multi-pen design will look nice, but if you will not implement the design and fill in the schedule each week, then it does you no good. If you live and die by your phone, then using a calendar that is tied to your email account and will show up on your phone’s calendar is a good idea. If you know that you tend to overcommit yourself, then using a paper planner can allow you to take stock of everything you have going on in a given week (or month) before you commit to a certain course of action or activity.

When deciding where to slot in different law school tasks, you first need to assess what time of day you work best and what your other commitments are. If you are an early riser, then you might consider planning your days to start at 7:00 am, when the law library opens. If you do your best work in the late hours of the evening, then your time slots you work with might include 10:00 pm and later. Your weekly schedule should also include when you plan to exercise and your routine social activities you plan to continue. You should not live and breathe law school, and if you try, you will find it is not sustainable.

I also recommend that every student take a full twenty-four hours off from law school studies every week. For instance, you would stop working on law school coursework at 6:00 pm on Friday evening and not begin working again until 6:00 pm on Saturday evening. Have this twenty-four-hour break be a goal for which you strive. There will be times where you do not think you can take the full time off, and you should not feel guilty about failing to take time off.

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg credited motherhood and time management for her law school success. In an interview with The Atlantic, Justice Ginsburg stated,

I attribute my success in law school largely to Jane. I went to class at 8:30 a.m., and I came home at 4:00 p.m., that was children’s hour. It was a total break in my day, and children’s hour continued until Jane went to sleep. Then I was happy to go back to the books, so I felt each part of my life made me rested from the other.

Daniel Lombroso, Jackie Lay & Ryan Park, Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Perspective That Comes With Motherhood, The Atlantic (Feb. 6, 2017), https://www.theatlantic.com/video/in...rg-motherhood/.

Similar to Justice Ginsburg’s time management model, many law school graduates recommend that students treat law school like a job. Setting time constraints on law school work and trying to stick with them will ensure that your working time is more productive and your free time is more enjoyable.

When deciding how long to spend on each activity before you transition to something else, you should consider what is a reasonable amount of time that you can actually focus. Do not create a weekly schedule that is aspirational and that you would like to be able to complete. You need to work within what is achievable for you. Be realistic. You will not want to spend six hours in a row reading for all of your classes, and frankly, you will not be able to retain the information as well.

Think about how to chunk your time into manageable pieces. I typically block things out for one-and-a-half to two hours, and I expect that once every thirty minutes I will spend about five minutes doing something else: getting a snack, refilling my coffee cup, checking my email, or scrolling on social media.

Another benefit of chunking your time is when you apply this concept to your longer-term and bigger projects. In addition to your readings for classes and then outlining your notes after class, you might also have midterms that you will need to study for and writing assignments to complete. When you receive a big assignment or need to study for an exam, find ways to break down the large assignment into smaller units. For instance, rather than thinking, “ARGH I HAVE TO RE-READ EVERYTHING I HAVE EVER LEARNED ABOUT CIVIL PROCEDURE RIGHT NOW,” you can instead approach your studies by saying, “Ok, on Monday and Tuesday I will review my notes and test myself on personal jurisdiction. Then, on Wednesday and Thursday, I will review what constitutes notice to the defendant.”

Similarly, when you receive a large writing assignment, decide how to break down the assignment into smaller parts and then schedule those smaller parts. That could look like deciding to read facts and take notes for one section of time, then to design a research plan for another section, and then to implement the research plan over three different sections of time.

Also consider how hard you perceive the different tasks to be. If you think reading for Contracts is a piece of cake but Torts trips you up, then plan to read for Torts at a time when you feel like you have better focus and drive to get the work done. When something is more challenging, it takes more concentration to get the task completed. You want to weave your harder and easier tasks together.

You should commit to coming up with a new schedule each week. What each of your classes requires from you may change each week, and certainly over the course of the semester you will have larger assignments that you will need to devote time to completing. At the end of the semester, when you shift to preparing for finals, you will still benefit from making a schedule each week so that you can see where you have time to study for each of your subjects.

At the beginning of law school, you are going to feel like you are relearning how to read and study; you will wonder how you are ever going to find three hours to read ten pages of material for each of your classes. You might be frustrated and begin to doubt yourself. Please believe me when I tell you that you will develop the skills to read and study more efficiently as you keep practicing. You will not need as much time to read, even at the end of the first semester, as you do at the very beginning.

A final note about scheduling your time: when you participate in an internship or work during the summers between law school and when you start your career after you graduate, having a tried-and-true system to manage your time and meet your responsibilities in a timely fashion will greatly benefit you and your supervisors.

Working in the Schedule, or Actually Getting Work Done When You Said You Would

The more challenging part to effectively managing your time is not planning when you will accomplish tasks but rather ensuring that you actually do accomplish those tasks. By sticking to the schedule you create (and giving yourself grace to deviate from it when necessary), the “present you” is benefitting the “future you” by ensuring that you are completing work along the way and without being rushed or running out of time to get done what you need to do. Trust me, at the end of November ,“future you” will really appreciate “present you” doing work along the way.

Chunking your time, as discussed above, can also help within your individual work sessions. One popular way to apportion your time is to use the Pomodoro Technique, an approach that was developed by Franciso Cirillo. The basic premise of the Pomodoro Technique is that you commit to yourself that you will focus only on the task you have assigned yourself for that period of time. The Technique calls for you to set your timer for twenty-five minutes, and once the timer goes off, you give yourself a short break of around five minutes. After four rounds with the timer (or approximately two hours), you give yourself a longer break. Forest, a study app available on any smart device, is a great tool for accountability and tracking progress throughout your work day. Using the Pomodoro Technique, for every twenty-five-minute interval of work completed, a tree is planted in your virtual “forest.” This encourages time away from your phone and improves productivity.

Another way that chunking can benefit you is for you to set your intention at the beginning of the work session. Being clear in what you want to accomplish allows you to meet benchmarks and to know when you can consider yourself “finished” with that assignment. For instance, you could determine that your goal for between 1:00 and 1:25 is to read and annotate four pages of material. Once you have completed that task, you can mentally (or literally) check it off your to-do list and move on to the next item. Giving yourself objective and measurable goals allows you to ease the feeling that many of you might experience that you have not ever done as much as you could and there is always something more to be done.

Conclusion

Part of success in law school, legal practice, or whatever career you pursue will be the result of finding the best system that allows you to produce quality work while still taking care of your mental well-being, maintaining connections to loved ones, and enjoying hobbies and other interests. The earlier you find and implement a system that works for you, the more successful and happier you will be.

Below are two weekly schedules to show you examples of how you can arrange your time to get you kickstarted in finding your best system.