2.4: Argument

- Page ID

- 69210

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)This chapter’s contents come from the original chapter on Argument in the first edition of Writing Unleashed.

Why Argue?16

We don’t always argue to win. Yes, you read that correctly. Argumentation isn’t always about being “right.” We argue to express opinions and explore new ideas. When writing an argument, your goal is to convince an audience that your opinions and ideas are worth consideration and discussion.

When instructors use the word "argument," they're talking about defending a certain point of view through writing or speech. Usually called a "claim" or a "thesis," this point of view is concerned with an issue that doesn't have a clear right or wrong answer (e.g., four and two make six). Also, this argument should not only be concerned with personal opinion (e.g., I really like carrots). Instead, an argument might tackle issues like abortion, capital punishment, stem cell research, or gun control. However, what distinguishes an argument from a descriptive essay or "report" is that the argument must take a stance; if you're merely summarizing "both sides" of an issue or pointing out the "pros and cons," you're not really writing an argument. "Stricter gun control laws will likely result in a decrease in gun-related violence" is an argument. Note that people can and will disagree with this argument, which is precisely why so many instructors find this type of assignment so useful – these assignments make you think!

Academic arguments usually "articulate an opinion." This opinion is always carefully defended with good reasoning and supported by plenty of research. Research? Yes, research! Indeed, part of learning to write effective arguments is finding reliable sources (or other documents) that lend credibility to your position. It's not enough to say, "capital punishment is wrong because that's the way I feel."

Instead, you need to adequately support your claim by finding:

- facts

- statistics

- quotations from recognized authorities, and

- other types of evidence

You won't always win, and that's fine. The goal of an argument is simply to:

- make a claim

- support your claim with the most credible reasoning and evidence you can muster

- hope that the reader will at least understand your position

- hope that your claim is taken seriously

What is an Argument?

Billboards, television advertisements, documentaries, political campaign messages, and even bumper stickers are often arguments – these are messages trying to convince an audience to do something. But be aware that an academic argument is different. An academic argument requires a clear structure and use of outside evidence.

KEY FEATURES OF AN ARGUMENT

- Clear Structure: Includes a claim, reasons/evidence, counterargument, and conclusion.

- Claim: Your arguable point (most often presented as your thesis statement).

- Reasons & Evidence: Strong reasons and materials that support your claim.

- Consideration of other Positions: Acknowledge and refute possible counterarguments.

- Persuasive Appeals: Use of appeals to emotion, character, and logic.

- Organizing an Argument

The great thing about the argument structure is its amazingly versatility. Once you become familiar with this basic structure of the argumentative essay, you will be able to clearly argue about almost anything! Next up is information all about the basic structure…

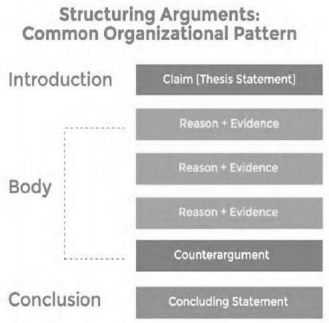

The Structure of an Argument18

If you are asked to write an argument, there is a basic argument structure. Use this outline to help create an organized argument:

- Introduction: Begin with an attention-getting introduction. Establish the need to explore this topic. Thesis Statement: What’s your claim?

- Brief background on issue (optional).

- Reasons & Evidence: First reason for your position (with supporting evidence)

- Second reason for your position (with supporting evidence)

- Additional reasons (optional)

- Counterargument: What’s the other side of the issue? Explain why your view is better than others.

- Conclusion: Summarize the argument. Make clear what you want the audience to think or do.

\(\PageIndex{1}\): Image used in previous OER textbook, Writing Unleashed, the non-argumentative one. This has been placed in greyscale for easier printing.

INTRODUCTION:

The first paragraph of your argument is used to introduce your topic and the issues surrounding it. This needs to be in clear, easily understandable language. Your readers need to know what you're writing about before they can decide if they believe you or not.

Once you have introduced your general subject, it's time to state your claim. Your claim will serve as the thesis for your essay. Make sure that you use clear and precise language. Your reader needs to understand exactly where you stand on the issue. The clarity of your claim affects your readers' understanding of your views. Also, it's a good idea to highlight what you plan to cover. Highlights allow your reader to know what direction you will be taking with your argument.

You can also mention the points or arguments in support of your claim, which you will be further discussing in the body. This part comes at the end of the thesis and can be named as the guide. The guide is a useful tool for you as well as the readers. It is useful for you, because this way you will be more organized. In addition, your audience will have a clearcut idea as to what will be discussed in the body.

BODY PARAGRAPHS:

Once your position is stated you should establish your credibility. There are two sides to every argument. This means not everyone will agree with your viewpoint. So, try to form a common ground with the audience. Think about who may be undecided or opposed to your viewpoint. Take the audience's age, education, values, gender, culture, ethnicity, and all other variables into consideration as you introduce your topic. These variables will affect your word choice, and your audience may be more likely to listen to your argument with an open mind if you do.

DEVELOPING YOUR ARGUMENT:

Back up your thesis with logical and persuasive arguments. During your pre-writing phase, outline the main points you might use to support your claim, and decide which are the strongest and most logical. Eliminate those which are based on emotion rather than fact. Your corroborating evidence should be well-researched, such as statistics, examples, and expert opinions. You can also reference personal experience. It's a good idea to have a mixture. However, you should avoid leaning too heavily on personal experience, as you want to present an argument that appears objective as you are using it to persuade your reader.

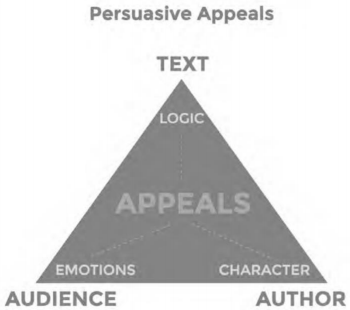

How to Be Persuasive?

Building an argument isn’t easy, and building a convincing argument is even more difficult. You may have a clear claim, solid reasons and evidence, and even refute the main counterargument, but your audience may not be convinced. Maybe they don’t care about the topic. Maybe they don’t find you credible. Or, maybe they find your evidence weak.

Here are the identified three means of persuasion:

- Logos: Use of evidence and reason to support the claim.

- Pathos: Appeals to the audience’s emotions and values.

- Ethos: An author leverages trustworthiness and character.

\(\PageIndex{2}\): This visual was created by Dana Anderson using Piktochart.com. This has been placed in greyscale for easier printing

To build a convincing and perhaps influential argument, you need to not only have a structurally sound argument (claim, reasons, evidence, counterargument, conclusion), but you also need to leverage appeals to persuade your audience. Arguments are complex and difficult to master. But understanding how to build and critically read arguments is essential in understanding and shaping our lives.

STRENGTHENING YOUR ARGUMENT18

It is important to clearly state and support your position. However, it is just as important to present all of the information that you've gathered in an objective manner. Using language that is demeaning or non-objective will undermine the strength of your argument. This destroys your credibility and will reduce your audience on the spot. For example, a student writing an argument about why a particular football team has a good chance of "going all the way" is making a strategic error by stating that "anyone who doesn't think that the Minnesota Vikings deserve to win the Super Bowl is a total idiot." Not only has the writer risked alienating any number of her readers, she has also made her argument seem shallow and poorly researched. In addition, she has committed a third mistake: making a sweeping generalization that cannot be supported.

OBJECTIVE LANGUAGE

Some instructors tell you to avoid using "I" and "My" (subjective) statements in your argument. You should only use "I" or "My" if you are an expert in your field (on a given topic). Instead choose more objective language to get your point across.

Consider the following:

I believe that the United States Government is failing to meet the needs of today's average college student through the under-funding of need-based grants, increasingly restrictive financial aid eligibility requirements, and a lack of flexible student loan options.

"Great," your reader thinks, "Everyone's entitled to their opinion."

Now let’s look at this sentence again, but without the "I" at the beginning. Does the same sentence become a strong statement of fact without your "I" tacked to the front?

The United States Government is failing to meet the needs of today's average college student through the underfunding of need-based grants, increasingly restrictive financial aid eligibility requirements, and a lack of flexible student loan options.

"Wow," your reader thinks, "that really sounds like a problem."

A small change like the removal of your "I"s and "my"s can make all the difference in how a reader perceives your argument – as such, it's always good to proofread your rough draft and look for places where you could use objective rather than subjective language.

A Note About Audience When Arguing

Many topics that are written about in college are very controversial. When approaching a topic, it is critical that you think about all of the implications that your argument makes. If, for example, you are writing a paper on abortion, you need to think about your audience. There will certainly be people in each of your classes that have some sort of relationship to this topic that may be different than yours. While you shouldn't let others' feelings sway your argument, you should approach each topic with a neutral mind and stay away from personal attacks. Keep your mind open to the implications of the opposition and formulate a logical stance considering the binaries equally. People may be offended by something you say, but if you have taken the time to think about the ideas that go into your paper, you should have no problem defending it.

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER WHEN ARGUING19

- How would your relatives react to the argument? Would they understand the terminology you are using? Does that matter?

- How would your friends react to the argument? Would they understand the terminology you are using? Does that matter?

- How would you explain your argument or research to a teenager vs someone who is in their 70s? Is there a difference?

- If you are aware that your classmates are more liberal or more conservative in their political standing, does that determine how you will argue your topic? Or does that even matter?

- If you are aware that your instructor is more liberal or conservative than you are, does that determine how you will argue your topic? Or does that even matter?

- If you were to people-watch at a mall or other space where many people gather, who in the crowd would be your ideal audience and why? Who is not your ideal audience member? Why?

Counterargument20

Speaking of audience, there are three main strategies for addressing counterargument:

- Acknowledgement: This acknowledges the importance of a particular alternative perspective but argues that it is irrelevant to the writer’s thesis/topic. When using this strategy, the writer agrees that the alternative perspective is important, but shows how it is outside of their focus.

- Accommodation: This acknowledges the validity of a potential objection to the writer’s thesis and how on the surface the objection and thesis might seem contradictory. When using this strategy, the writer goes on to argue that, however, the ideal expressed in the objection is actually consistent with the writer’s own goals if one digs deeper into the issue.

- Refutation: This acknowledges that a contrary perspective is reasonable and understandable. It does not attack differing points of view. When using this strategy, the writer responds with strong, research-based evidence showing how that other perspective is incorrect or unfounded.

EXAMPLES

Let’s see how these three strategies could work in practice by considering the thesis statement “Utah public schools need to invest more money in arts education.”

- Acknowledgement: One possible objection to the thesis could be: “Athletics are also an important part of students’ educational experience.” The writer could acknowledge that athletics are indeed important, but no more important than the arts. A responsible school budget should be able to include both.

- Accommodation: Another possible objection to this thesis could be: “Students need a strong foundation in STEM subjects in order to get into college and get a good career.” The writer could acknowledge that STEM education is indeed crucial to students’ education. They could go on to argue, however, that arts education helps students be stronger in STEM classes through teaching creative problem solving. So, if someone values STEM education, they need to value the arts as well.

- Refutation: The most common objection to education budget proposals is that there is simply not enough money. Given limited resources, schools have to prioritize where money is spent. In terms of research required, refutation takes the most work of these three methods. To argue that schools do have enough resources to support arts education, the writer would need to look at current budget allocations. They could Google “Salt Lake City school district budget” to find a current budget report. In this report, they would find that the total budget for administrative roles in the 2014–15 school year totaled $10,443,596 (Roberts and Kearsley21). Then they could argue that through administrative reforms, a small portion of this money could be freed up to make a big difference in funding arts education.

EXAMPLE: “CAN GRAFFITI EVER BE CONSIDERED ART?”22

Graffiti is not simply acts of vandalism, but a true artistic form because of personal expression, aesthetic qualities, and movements of style.

Graffiti, like traditional artistic forms such as sculpture, is art because it allows artists to express ideas through an outside medium.

Graffiti must be considered an art form based on judgement of aesthetic qualities. Art professor George C. Stowers argues that “larger pieces require planning and imagination and contain artistic elements like color and composition” (“Graffiti”).

Like all artistic forms, Graffiti has evolved, experiencing significant movements or periods.

Often, graffiti is seen as only criminal vandalism, but this is not always the case. The artistic merits of graffiti–expression, aesthetics, and movements–cannot be denied; Graffiti is art.

Works Cited

“Graffiti: Art through Vandalism.” Graffiti: Art through Vandalism. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Sept. 2015.

Assignments or Questions to Consider

Compose an argument that answers the following: Do grades in any course reflect who you are as a student or how much you have learned? Think on any college or high school course you’ve taken – did that letter grade reflect what you learned? Why or why not? Do letter grades represent a student’s ability or intelligence? Your answers to these questions will become an argument. At a minimum, include the following:

- Some sort of structure: intro, body, conclusion

- An argumentative thesis

- Three pieces of evidence that back your thesis

- One quality source integrated into the text and cited correctly at the end

16 “What is an Argument?” Wikibooks, The Free Textbook Project. Last edited 27 Nov 14. Accessed 10 May 17. https://en.m.wikibooks.org/wiki/Rhet...ition/Argument Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

17 “What is an Argument?” Wikibooks, The Free Textbook Project. Last edited 27 Nov 14. Accessed 10 May 17. https://en.m.wikibooks.org/wiki/Rhet...ition/Argument. Text is available under the CC-BY-SA.

18 “What is an Argument?” Wikibooks, The Free Textbook Project. Last edited 27 Nov 14. Accessed 10 May 17. en.m.wikibooks.org/wiki/Rhet...ition/Argument. Licensed CC-BY-SA.

19 Questions taken from a longer piece by: Jory, Justin. “A Word About Audience.” Open English at Salt Lake Community College. 01 Aug 2016. https://openenglishatslcc.pressbooks...pter/audience/ Open English @ SLCC by SLCC English Department is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

20 Taken from a longer piece by: Beatty, Jim. “Counterargument.” Open English at Salt Lake Community College. 01 Aug 2016. https://openenglishatslcc.pressbooks...unterargument/ Open English @ SLCC by SLCC English Department is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

21 Roberts, Janet M. and Alan T. Kearsley. “Annual Budget Fiscal Year 2014-2015.” Salt Lake City School District. http://www.slcschools.org/department...415-Budget.pdf. Accessed 3 December 2017. Taken from a longer piece by: Beatty, Jim. “Counterargument.” Open English at Salt Lake Community College. 01 Aug 2016. https://openenglishatslcc.pressbooks...unterargument/ Open English @ SLCC by SLCC English Department is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

22 Example used in previous OER textbook, Writing Unleashed.