2.2: While Reading Strategies

- Page ID

- 225891

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE TOPIC, MAIN IDEA AND THE MAJOR/MINOR IDEAS IN A TEXT?

| OVERVIEW: | DEFINITION: | QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF: |

|---|---|---|

| TOPIC = WHAT THE TEXT IS ABOUT |

The topic states the subject matter but does not state an opinion on it. | What specific topic does this text focus on? |

| MAIN IDEA = THESIS | The main idea is the thesis, also known as the central argument. | What is the main idea the author wants me to learn or wants to convince me of in this text? |

| MAJOR IDEAS = KEY SUPPORTING POINTS PROVING THE MAIN IDEA |

Each major idea states one reason that supports and proves the thesis. | What reasons did the author use to convince me of his/her thesis? |

| MINOR IDEAS = EVIDENCE AND ANALYSIS ILLUSTRATING THE MAJOR IDEAS |

Minor ideas are used to illustrate and explain the major ideas. | What specific evidence (examples, data, etc) did the author use to illustrate the major ideas and did s/he add analysis or explanation to further convince me? |

WHY IDENTIFY THEM WHEN READING?

- You can fully understand a text when you can identify all its elements.

- It removes any confusion about the purpose of a text.

- When you can clearly see the different parts of a text, you can make a more educated assessment of the text and directly respond with your own viewpoints.

HOW DO I IDENTIFY THEM?

Here is a 4-step process to identify these different elements in a text:

(1) Note the topic as you’re reading. To figure out the topic, note what all the sentences in the text are centered on and use the guiding question: What specific topic does this text focus on?

(2) Label the main idea when you find it. To locate it, use the guiding question: What is the main idea the author wants me to learn or wants to convince me of in this text? If the thesis is implied (not directly stated), examine the clues in the text and then write in your own words what you think the author’s main purpose or central argument is.

(3) Label the major ideas when you read them (sometimes you can even number the reasons as you identify them). To locate them, use the guiding question: What reasons did the author use to convince me of his/her thesis?

(4) Note the minor ideas when you read them. To locate them, use the guiding questions: What specific evidence (examples, data, etc) did the author use to illustrate the major ideas and did s/he add analysis or explanation to further convince me?

Using the second paragraph of Chapter VII in the excerpt from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, locate the topic and main idea as well as the major and minor ideas:

My mistress was, as I have said, a kind and tender-hearted woman; and in the simplicity of her soul she commenced, when I first went to live with her, to treat me as she supposed one human being ought to treat another. In entering upon the duties of a slaveholder, she did not seem to perceive that I sustained to her the relation of a mere chattel, and that for her to treat me as a human being was not only wrong, but dangerously so. Slavery proved as injurious to her as it did to me. When I went there, she was a pious, warm, and tender-hearted woman. There was no sorrow or suffering for which she had not a tear. She had bread for the hungry, clothes for the naked, and comfort for every mourner that came within her reach. Slavery soon proved its ability to

divest her of these heavenly qualities. Under its influence, the tender heart became stone, and the lamblike disposition gave way to one of tiger-like fierceness. The first step in her downward course was in her ceasing to instruct me. She now commenced to practise her husband's precepts. She finally became even more violent in her opposition than her husband himself. She was not satisfied with simply doing as well as he had commanded; she seemed anxious to do better. Nothing seemed to make her more angry than to see me with a newspaper. She seemed to think that here lay the danger. I have had her rush at me with a face made all up of fury, and snatch from me a newspaper, in a manner that fully revealed her apprehension. She was an apt woman; and a little experience soon demonstrated, to her satisfaction, that education and slavery were incompatible with each other.

- Answer

-

Using the second paragraph of Chapter VII in the excerpt from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, locate the topic and main idea as well as the major and minor ideas:

(1) Note the topic as you’re reading.

(2) Label the main idea when you find it (or put it in your own words).

(3) Label the major ideas when you read them.

(4) Note the minor ideas when you read them.

TOPIC: Influence of slavery (“slavery” for example, would be too general for this paragraph and “slaves learning to read” would be a more appropriate topic for all of Chapter VII)

MAIN IDEA/THESIS: “Slavery proved as injurious to her as it did to me.”

MAJOR IDEAS (REASONS) PROVING THE MAIN IDEA/THESIS:

(1) “She was a pious, warm, and tender-hearted woman.”

(2) “Under [slavery’s] influence, the tender heart became stone, and the lamblike disposition gave way to one of tiger-like fierceness.”

MINOR IDEAS (EVIDENCE AND ANALYSIS) ILLUSTRATING THE MAJOR IDEAS:

Supporting major idea #1: “She was a pious, warm, and tender-hearted woman.”

(a) “There was no sorrow or suffering for which she had not a tear. “

(b) “She had bread for the hungry, clothes for the naked, and comfort for every mourner that came within her reach.”

Supporting major idea #2: “Under [slavery’s] influence, the tender heart became stone, and the lamblike disposition gave way to one of tiger-like fierceness.”

(a) “The first step in her downward course was in her ceasing to instruct me. She now commenced to practise her husband's precepts.”

(b) “She finally became even more violent in her opposition than her husband himself. She was not satisfied with simply doing as well as he had commanded; she seemed anxious to do better.”

(c) “Nothing seemed to make her more angry than to see me with a newspaper. She seemed to think that here lay the danger. I have had her rush at me with a face made all up of fury, and snatch from me a newspaper, in a manner that fully revealed her apprehension.”

(d) “She was an apt woman; and a little experience soon demonstrated, to her satisfaction, that education and slavery were incompatible with each other.”

WHAT IS ANNOTATING?

Annotating is an organized method to take notes as you read and involves marking up a text as you read it. It usually involves adding your own thoughts, questions and observations in the margins, circling unknown terms and vocabulary, underlining or highlighting main points and good quotes, and coding (briefly summing up passages in a few key words).

WHY IS ANNOTATING IMPORTANT?

- It turns you into an active reader engaging closely with the text.

- Being an active reader improves comprehension and retention of what you read.

- You can use your notes to select material to include in a more formal paper.

- It can help you better understand complex texts through breaking them down.

- You can circle unknown terms and then look them all up after you are finished reading (looking them up as you read will disrupt your understanding and enjoyment of the text)

- You can navigate a well-marked text quickly to find quotes and evidence for papers and open book exams.

- You can refresh your memory of the text easily by re-reading your notes and what you have highlighted without having to re-read the entire text.

HOW DO I ANNOTATE?

There are different methods for marking a text. Often you will use a variety of the following methods AS YOU READ:

- In the text margins, write your own questions and comments that come up.

- Underline and/or highlight the main points and good quotes (don’t over highlight—be selective).

- Circle unknown vocabulary and after you read, look up the words and write in the definitions.

- Code as you read which means to write a one-to-three word description that captures the essence of large chunks or paragraphs of text. This will create an easy to follow summary in the margins.

- If the thesis (main argument or purpose of the text) is stated, write “thesis” next to it or if it is implied (not stated) use the clues from the text to figure it out and then write out the thesis in your own words.

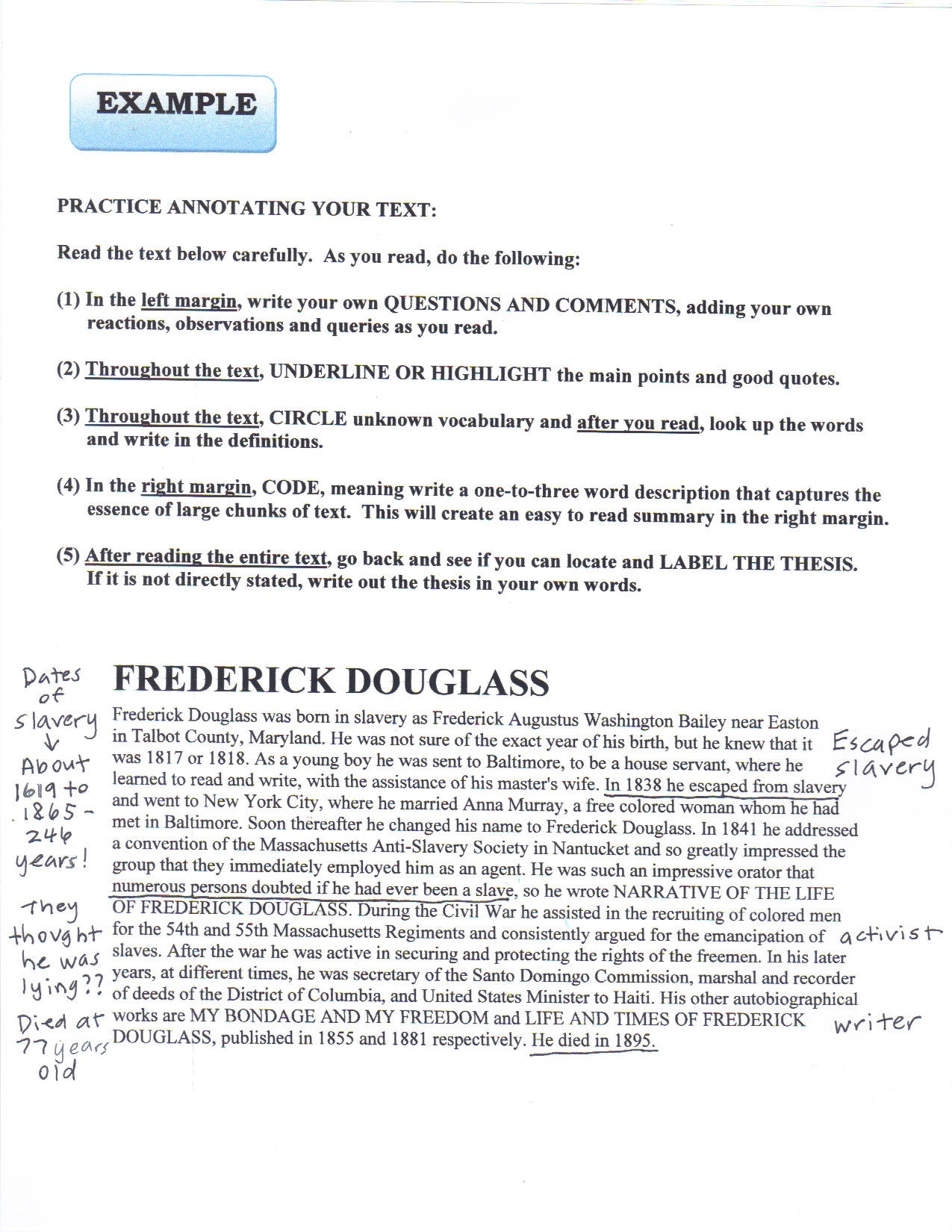

Read the text below carefully. As you read, do the following:

(1) In the left margin, write your own QUESTIONS AND COMMENTS, adding your own reactions, observations and queries as you read.

(2) Throughout the text, UNDERLINE OR HIGHLIGHT the main points and good quotes.

(3) Throughout the text, CIRCLE unknown vocabulary and after you read, look up the words and write in the definitions.

(4) In the right margin, CODE, meaning write a one-to-three word description that captures the essence of large chunks of text. This will create an easy to read summary in the right margin.

(5) After reading the entire text, go back and see if you can locate and LABEL THE THESIS. If it is not directly stated, write out the thesis in your own words.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Frederick Douglass was born in slavery as Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey near Easton in Talbot County, Maryland. He was not sure of the exact year of his birth, but he knew that it was 1817 or 1818. As a young boy he was sent to Baltimore, to be a house servant, where he learned to read and write, with the assistance of his master's wife. In 1838 he escaped from slavery and went to New York City, where he married Anna Murray, a free colored woman whom he had met in Baltimore. Soon thereafter he changed his name to Frederick Douglass. In 1841 he addressed a convention of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society in Nantucket and so greatly impressed the group that they immediately employed him as an agent. He was such an impressive orator that

numerous persons doubted if he had ever been a slave, so he wrote NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE OF FREDERICK DOUGLASS. During the Civil War he assisted in the recruiting of colored men for the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Regiments and consistently argued for the emancipation of slaves. After the war he was active in securing and protecting the rights of the freemen. In his later years, at different times, he was secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission, marshal and recorder of deeds of the District of Columbia, and United States Minister to Haiti. His other autobiographical works are MY BONDAGE AND MY FREEDOM and LIFE AND TIMES OF FREDERICK DOUGLASS, published in 1855 and 1881 respectively. He died in 1895.

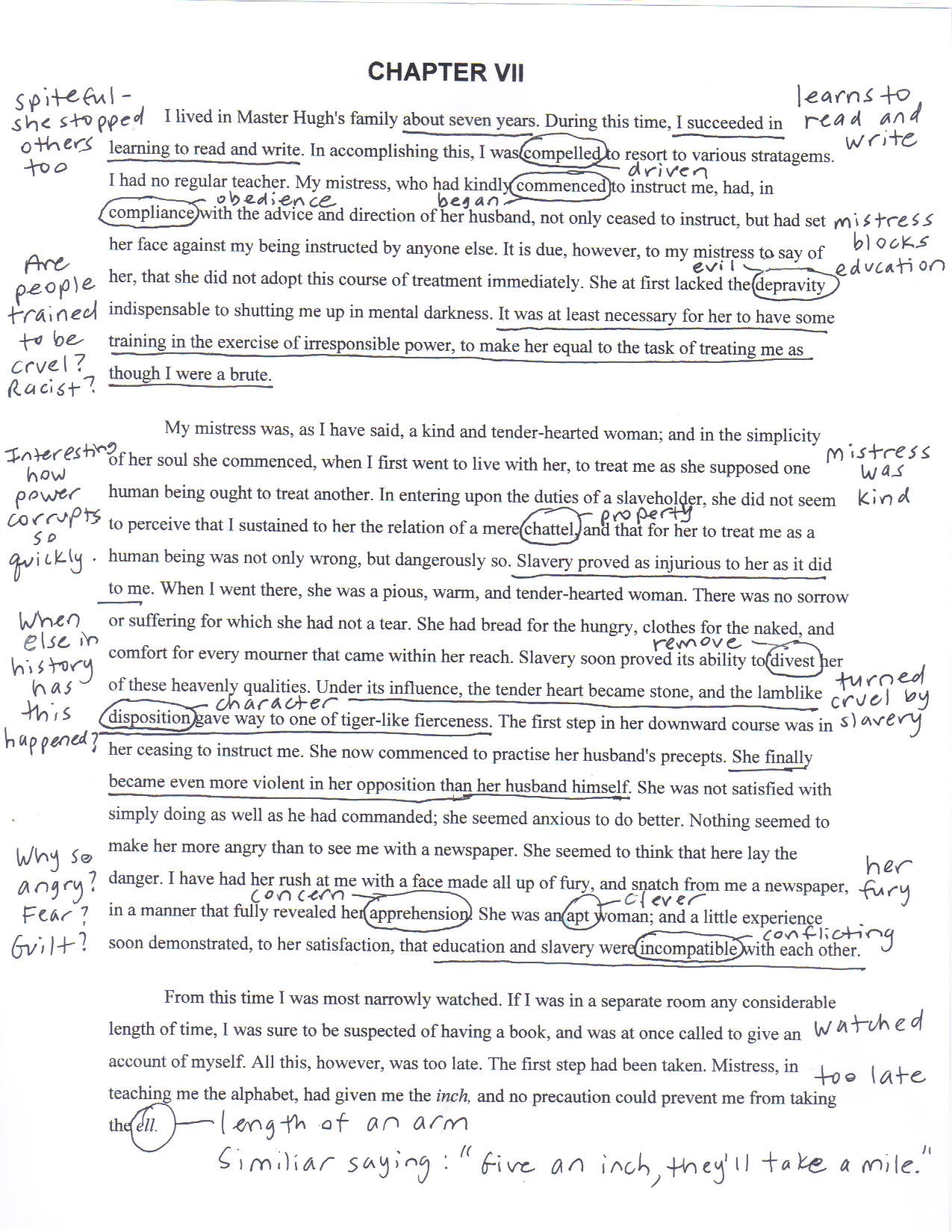

CHAPTER VII

I lived in Master Hugh's family about seven years. During this time, I succeeded in learning to read and write. In accomplishing this, I was compelled to resort to various stratagems. I had no regular teacher. My mistress, who had kindly commenced to instruct me, had, in compliance with the advice and direction of her husband, not only ceased to instruct, but had set her face against my being instructed by anyone else. It is due, however, to my mistress to say of her, that she did not adopt this course of treatment immediately. She at first lacked the depravity indispensable to shutting me up in mental darkness. It was at least necessary for her to have some training in the exercise of irresponsible power, to make her equal to the task of treating me as though I were a brute.

My mistress was, as I have said, a kind and tender-hearted woman; and in the simplicity of her soul she commenced, when I first went to live with her, to treat me as she supposed one human being ought to treat another. In entering upon the duties of a slaveholder, she did not seem to perceive that I sustained to her the relation of a mere chattel, and that for her to treat me as a human being was not only wrong, but dangerously so. Slavery proved as injurious to her as it did to me. When I went there, she was a pious, warm, and tender-hearted woman. There was no sorrow or suffering for which she had not a tear. She had bread for the hungry, clothes for the naked, and comfort for every mourner that came within her reach. Slavery soon proved its ability to divest her of these heavenly qualities. Under its influence, the tender heart became stone, and the lamblike disposition gave way to one of tiger-like fierceness. The first step in her downward course was in her ceasing to instruct me. She now commenced to practise her husband's precepts. She finally became even more violent in her opposition than her husband himself. She was not satisfied with simply doing as well as he had commanded; she seemed anxious to do better. Nothing seemed to make her more angry than to see me with a newspaper. She seemed to think that here lay the danger. I have had her rush at me with a face made all up of fury, and snatch from me a newspaper, in a manner that fully revealed her apprehension. She was an apt woman; and a little experience soon demonstrated, to her satisfaction, that education and slavery were incompatible with each other.

From this time I was most narrowly watched. If I was in a separate room any considerable length of time, I was sure to be suspected of having a book, and was at once called to give an account of myself. All this, however, was too late. The first step had been taken. Mistress, in teaching me the alphabet, had given me the inch, and no precaution could prevent me from taking the ell.

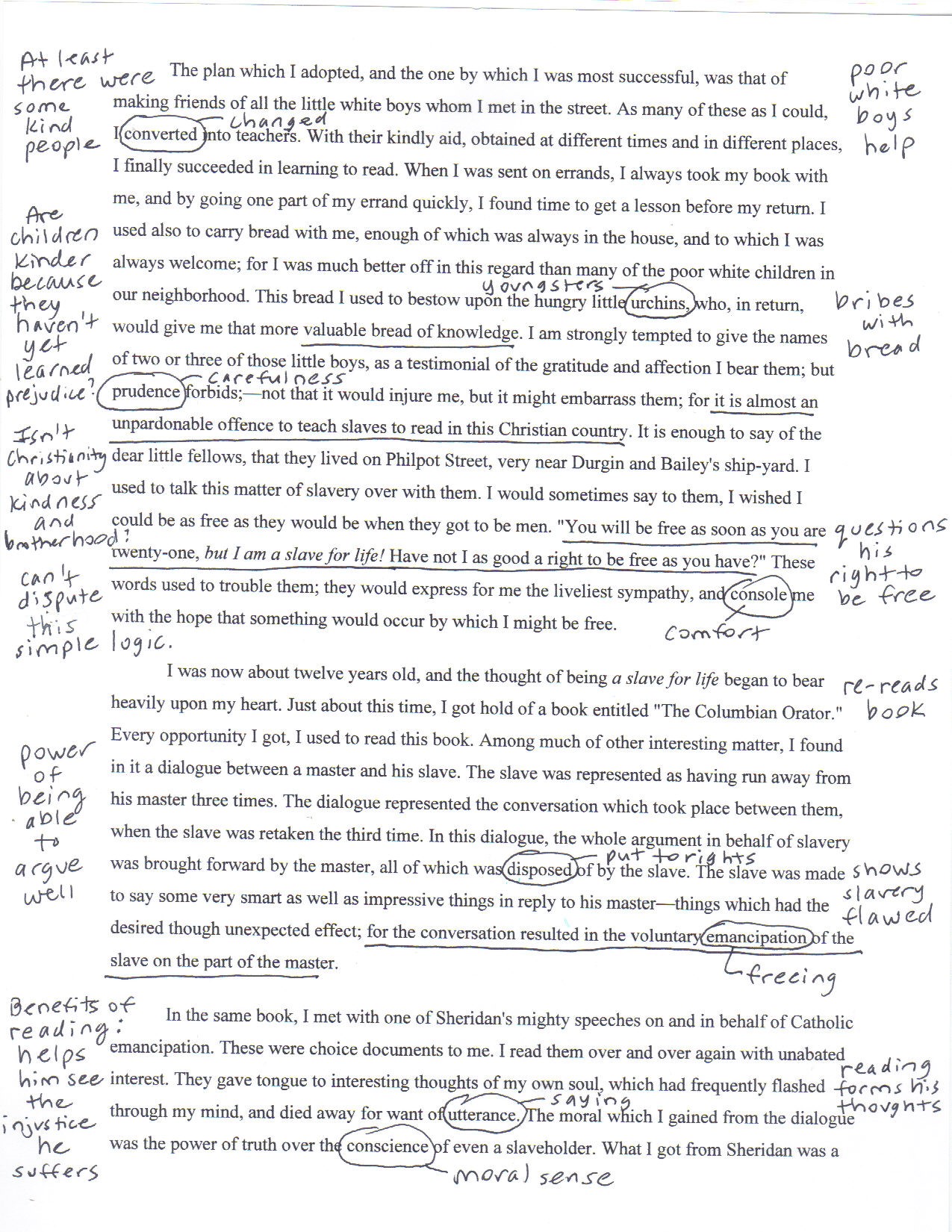

The plan which I adopted, and the one by which I was most successful, was that of making friends of all the little white boys whom I met in the street. As many of these as I could, I converted into teachers. With their kindly aid, obtained at different times and in different places, I finally succeeded in learning to read. When I was sent on errands, I always took my book with me, and by going one part of my errand quickly, I found time to get a lesson before my return. I used also to carry bread with me, enough of which was always in the house, and to which I was always welcome; for I was much better off in this regard than many of the poor white children in our neighborhood. This bread I used to bestow upon the hungry little urchins, who, in return, would give me that more valuable bread of knowledge. I am strongly tempted to give the names of two or three of those little boys, as a testimonial of the gratitude and affection I bear them; but prudence forbids;—not that it would injure me, but it might embarrass them; for it is almost an unpardonable offence to teach slaves to read in this Christian country. It is enough to say of the dear little fellows, that they lived on Philpot Street, very near Durgin and Bailey's ship-yard. I used to talk this matter of slavery over with them. I would sometimes say to them, I wished I could be as free as they would be when they got to be men. "You will be free as soon as you are twenty-one, but I am a slave for life! Have not I as good a right to be free as you have?" These words used to trouble them; they would express for me the liveliest sympathy, and console me with the hope that something would occur by which I might be free.

I was now about twelve years old, and the thought of being a slave for life began to bear heavily upon my heart. Just about this time, I got hold of a book entitled "The Columbian Orator." Every opportunity I got, I used to read this book. Among much of other interesting matter, I found in it a dialogue between a master and his slave. The slave was represented as having run away from his master three times. The dialogue represented the conversation which took place between them, when the slave was retaken the third time. In this dialogue, the whole argument in behalf of slavery was brought forward by the master, all of which was disposed of by the slave. The slave was made to say some very smart as well as impressive things in reply to his master—things which had the desired though unexpected effect; for the conversation resulted in the voluntary emancipation of the slave on the part of the master.

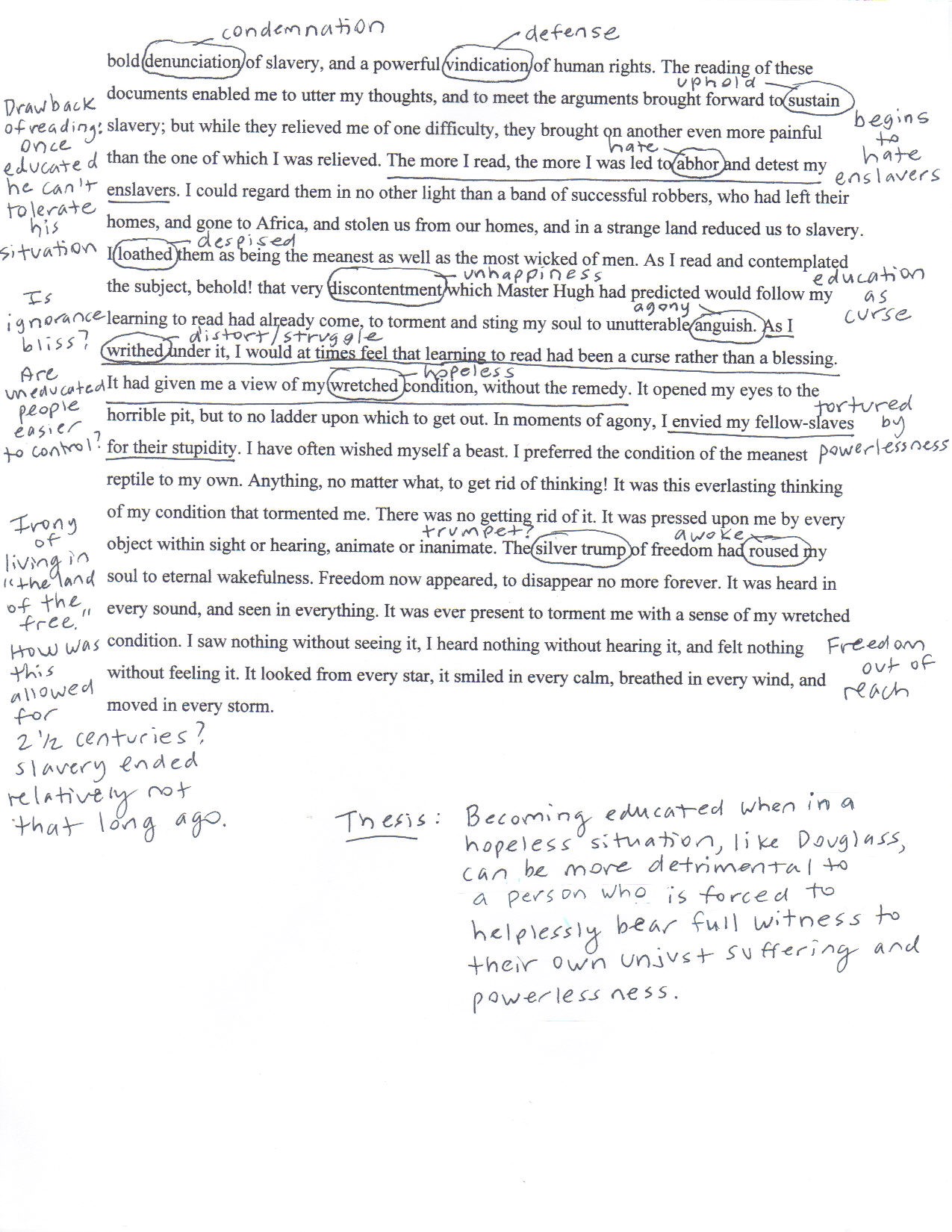

In the same book, I met with one of Sheridan's mighty speeches on and in behalf of Catholic emancipation. These were choice documents to me. I read them over and over again with unabated interest. They gave tongue to interesting thoughts of my own soul, which had frequently flashed through my mind, and died away for want of utterance. The moral which I gained from the dialogue was the power of truth over the conscience of even a slaveholder. What I got from Sheridan was a bold denunciation of slavery, and a powerful vindication of human rights. The reading of these documents enabled me to utter my thoughts, and to meet the arguments brought forward to sustain slavery; but while they relieved me of one difficulty, they brought on another even more painful than the one of which I was relieved. The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers. I could regard them in no other light than a band of successful robbers, who had left their homes, and gone to Africa, and stolen us from our homes, and in a strange land reduced us to slavery.

I loathed them as being the meanest as well as the most wicked of men. As I read and contemplated the subject, behold! that very discontentment which Master Hugh had predicted would follow my learning to read had already come, to torment and sting my soul to unutterable anguish. As I writhed under it, I would at times feel that learning to read had been a curse rather than a blessing. It had given me a view of my wretched condition, without the remedy. It opened my eyes to the horrible pit, but to no ladder upon which to get out. In moments of agony, I envied my fellow-slaves for their stupidity. I have often wished myself a beast. I preferred the condition of the meanest reptile to my own. Anything, no matter what, to get rid of thinking! It was this everlasting thinking of my condition that tormented me. There was no getting rid of it. It was pressed upon me by every object within sight or hearing, animate or inanimate. The silver trump of freedom had roused my soul to eternal wakefulness. Freedom now appeared, to disappear no more forever. It was heard in

every sound, and seen in everything. It was ever present to torment me with a sense of my wretched condition. I saw nothing without seeing it, I heard nothing without hearing it, and felt nothing without feeling it. It looked from every star, it smiled in every calm, breathed in every wind, and moved in every storm.

- Example

-

WHAT IS CHUNKING?

Chunking is visually grouping interrelated words as you read as opposed to reading one word at a time. You want to make meaningful groups of words and the point of fixation should be in the middle of the unit of words.

WHY IS CHUNKING IMPORTANT?

- Chunking speeds up your reading rate.

- Chunking enables you to process whole ideas rather than laboring word by word.

- Chunking improves comprehension by letting you get a “bigger picture” of the text.

HOW DO I DO IT?

Through practice, you can train your eye and your brain to focus on groups of words instead of individual words. Look at the following examples to see what this type of grouping looks and feels like as you read and then try applying the technique.

PASSAGE ONE: Slow Reader

A very slow reader who often also has poor compre hension fixates or stops at every single word and even divides words into syllables if the words seem too long. He is the word by word reader who plows through print with little under standing of what he reads.

PASSAGE TWO: Average Reader

The average reader, on the other hand, tries to see a few words each time his eyes stop but does so in a helter-skelter way and does not get much better comprehension than the slow reader. The average reader stops at every few words and tries to get meaning from them.

PASSAGE THREE: Good Reader

The efficient reader usually fixates in the middle of a group of words and reads thought units during each fixation. The better reader does not read single words. He does not look at the printed material in a helter-skelter way. He has trained his eyes to work in such a way that he perceives ideas in chunks or groups. He has become a smooth, rhythmical reader.

He reads in clusters, connecting ideas naturally.

WHAT ARE WORD PARTS?

Words parts come in a few different forms:

|

Prefix: An affix placed at the beginning of a word which changes its meaning. |

Root: The base of a word (with all affixes removed) that contains the core meaning of the word. |

Suffix: An affix placed at the end of a word and indicates the form of the word (i.e. noun, verb, adjective). |

Each word parts serves to build meaning, so learning word parts can dramatically expand your vocabulary because if you know part of an unknown word, you can make a quick and educated guess as to its meaning without having to consult a dictionary.

WHY FOCUS ON WORD PARTS?

- Learning word parts (rather than memorizing lists of vocabulary words) is more efficient for expanding your vocabulary because learning one word part can potentially help you figure out hundreds of words that contain that word part.

- Knowing word parts helps you quickly identify the function of a word in a sentence (i.e. if the word is a noun, a person, an action, an adjective).

- Having a broader vocabulary builds reading speed and comprehension.

HOW DO I USE WORD PARTS?

The first step is memorizing a series of word parts and applying that knowledge so that what you learn stays in your long-term memory. You can then apply this knowledge of word parts whenever you’re reading to figure out unfamiliar words quickly.

Prefixes - Set One

| Prefix: | Meaning: | Add an example under each given: | Use one of the examples in a sentence: |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. a- | without, not, opposite | atypical | |

| 2. ab- | away, from | abnormal | |

| 3. ad- | toward | advance | |

| 4. ambi- | both | ambiguous | |

| 5. anti- | against | antisocial | |

| 6. bene- | well, good | benefit | |

| 7. bi-, du-, di- | two or twice | bicycle, duplex, dichotomy | |

| 8. cent- | hundred | century | |

| 9. con-, com-, syn- | with, together | convene, complex, synthesize | |

| 10. de- | down, from | detract | |

| 11. dec, deca- | ten | decade, decadence | |

| 12. dia- | through | diameter | |

| 13. dis- | not, opposite of | dislike | |

| 14. ex- | out, from | exhale | |

| 15. hyper- | above, excessive | hyperactive | |

| 16. il-, im-, in- | not | illogical, immature, inability | |

| 17. im-, in- | in, into | import, inside | |

| 18. inter- | between | interrupt | |

| 19. intra- | within | intramurals | |

| 20. juxta- | next to | juxtaposition |

Prefixes - Set Two

| Prefix: | Meaning: | Add an example under each given: | Use one of the examples in a sentence: |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. mal-, mis- | wrong, ill | malformed, mistake | |

| 2. nove, non- | nine | novena, nonagon | |

| 3. oct-, octo- | eight | octet, octopus | |

| 4. omni- | all | omnipotent | |

| 5. per- | through | pervade | |

| 6. peri- | around | perimeter | |

| 7. poly- | many | polygamy | |

| 8. post- | after | postscript | |

| 9. pre- | before | prepared | |

| 10. quad-, quadra- | four | quadrilateral, quadrant | |

| 11. quint- | five | quintuplet | |

| 12. re- | back, again | review | |

| 13. retro- | backward | retrospect | |

| 14. sequ- | follow | sequence | |

| 15. sex- | six | sextet | |

| 16. sub- | under | submarine | |

| 17. temp- | time | tempo | |

| 18. trans- | across | translate | |

| 19. tri- | three | triangle | |

| 20. uni- | one | unicorn |

Roots - Set One

| Root: | Meaning: | Add an example under each given: | Use one of the examples in a sentence: |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. anima | breath, spirit | animate | |

| 2. aqua | water | aquarium | |

| 3. auto | self | autonomy | |

| 4. bio | life | biology | |

| 5. dent | teeth | dental | |

| 6. derma | skin | dermatologist | |

| 7. duc, duct | to lead | conducive, conduct | |

| 8. err, errat | to wander | error, erratic | |

| 9. ethno | race, tribe | ethnocentrism | |

| 10. fac, fact | to do, make | deface, manufacture | |

| 11. gene | race, kind, sex | genetics | |

| 12. grad | to go, take steps | graduation | |

| 13. gyn | woman | gynecologist | |

| 14. hab, habi | to have, hold | habanero, habitat | |

| 15. lith | stone | monolith | |

| 16. log | speech, science | dialogue | |

| 17. lum | light | illuminate | |

| 18. meter | to measure | barometer | |

| 19. miss, mit | to send, let go | missile, admit | |

| 20. mut, muta | to change | commute, mutation |

Roots - Set Two

| Root: | Meaning: | Add an example under each given: | Use one of the examples in a sentence: |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. neg, negat | to say no, deny | neglect, negative | |

| 2. ortho | right, straight | orthodox | |

| 3. pater | father | paternal | |

| 4. path | disease, feeling | pathology | |

| 5. phobia | fear | claustrophobia | |

| 6. phon, phono | sound | phonics, phonograph | |

| 7. plic | to fold | duplicate | |

| 8. pon, pos | to place | ponder, position | |

| 9. port | to carry | portable | |

| 10. psych | mind | psychology | |

| 11. pyr | fire | pyromaniac | |

| 12. quir | to ask | inquire | |

| 13. scrib | to write | prescribe | |

| 14. sol | alone | solitude | |

| 15. soph | wise | sophomore | |

| 16. soror | sister | sorority | |

| 17. tact | to touch | tactile | |

| 18. tele | distant | telephone | |

| 19. therm | heat | thermometer | |

| 20. tort | twist | torture |

Suffixes

| Suffix: | Meaning: | Add an example under each given: | Use one of the examples in a sentence: |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. -able, -ible | capable of | durable, tangible | |

| 2. -age | act of, state of | breakage | |

| 3. -al | pertaining to | rental | |

| 4. -ant | quality of, one who | servant | |

| 5. -arium, -orium | place for | aquarium, auditorium | |

| 6. -ate | cause to be | activate | |

| 7. -esque | like in manner | picturesque | |

| 8. -fic | making, causing | scientific | |

| 9. -form | in the shape of | chloroform | |

| 10. -ful | full of | beautiful | |

| 11. -fy | to make, cause to be | magnify | |

| 12. -hood | condition or state of | childhood | |

| 13. -ics | art, science | mathematics | |

| 14. -itis | inflammation of | appendicitis | |

| 15. -latry | worship of | idolatry | |

| 16. -less | without | homeless | |

| 17. -oid | in the form of | tabloid | |

| 18. -tude | quality or degree of | solitude | |

| 19. -wards | in a direction of | backwards | |

| 20. -wise | way, position | clockwise |

WHAT ARE CONTEXT CLUES?

Knowing word parts is one way to figure out the meaning of an unknown word. Another approach you can employ is using context clues. You can often unlock the meaning of a new word by analyzing the context of the sentence and paragraph in which it is used. The context is the part of a text or statement that surrounds a particular word or passage and determines its meaning.

WHY USE CONTEXT CLUES?

- Your reading isn’t slowed down by having to look words up in the dictionary.

- Paying more attention to context clues means you are reading on a more active and engaged level which will improve comprehension and retention of what you read.

- Your reading confidence increases as you can figure out complex language on your own.

HOW DO I USE CONTEXT CLUES?

Use different types of clues to help unlock the meaning of new words:

- Definition: The unknown word is defined within the sentence or paragraph. For example, the hungry campers started to devour the pizzas after having been in the wilderness for the past week, eagerly eating every crumb.

- Elaborating Details: Descriptive details suggest the meaning of the unknown word. For example, the young man in the photo had a striking and gaunt appearance. His clothes hung loosely on his thin body, as if he had not eaten in weeks.

- Elaborating Examples: An anecdote or example before or after the word suggests the meaning. For example, after three days at sea, the fishermen were famished. They said they could eat an entire whale if catching one were still allowed.

- Comparison: A similar situation suggests the meaning of the unknown word. For example, before being offered a generous five-year contract, the quarterback underwent more scrutiny than a fugitive being investigated by the FBI.

- Contrast: An opposite situation suggests the meaning of the unknown word. For example, even though she appears indefatigable during the workday, she is generally exhausted by 6pm.

Also use word parts:

- Prefixes: An affix placed at the beginning of a word which changes its meaning.

- Roots: The base of a word (with all affixes removed) that contains the core meaning of the word. The roots that we use in English are derived primarily from Latin and Greek.

- Suffixes: An affix placed at the end of a word and indicates the form of the word (i.e. noun, verb, adjective).

Read the paragraph below which contains prefixes from “Prefixes—Set One.” Afterwards, without using a dictionary give the definition of the italicized words using the context clues. Also give the definition of the prefix used.

Once there was a ruler of a country who was asked to abdicate her position because she had become unpopular with the people. A group of nobles interceded on her behalf arguing that she was a very beneficent ruler and that the reasons given by those asking for her removal were illogical and violated the sacred traditions of the country. They also argued that if she were removed, then anarchy would sweep the land. Those who demanded that she step down congregated in the main square of the capital and decided that if she would not willingly abdicate, then they would need to seek expel her but they knew this would be very difficult because the country’s laws on the issue of abdication were ambiguous and could therefore be manipulated by those sympathetic to the ruler. The people felt that not only did they want to remove the ruler herself but also the dichotomous system of government that gave only the ruler and the nobles any power or decision-making. They proposed more of a synthesis of power between the upper as well as lower classes.

|

Define the prefix ab-: |

Define the prefix con-: |

|

Define the prefix inter-: |

Define the prefix ex-: |

|

Define the prefix bene-: |

Define the prefix ambi-: |

|

Define the prefix il-: What context clues did you use: |

Define the prefix di-: What context clues did you use: |

|

Define the prefix a-: |

Define the prefix syn-: |

Read the paragraph below which contains prefixes from “Prefixes—Set Two.” Afterwards, without using a dictionary give the definition of the italicized words using the context clues. Also give the definition of the prefix used.

Maria and Anthony tried for many years to have children. With her perennial courage, Maria endured many corrective surgeries and treatments but to no avail. Finally, she tried fertility drugs even though she knew a woman who had done the same and her child came out malformed. Maria told Anthony that she wished she were omnipotent so that she could fix her difficulties without the use of medication. Maria had many negative preconceptions about the use of fertility drugs, but Anthony helped her learn the actual risks and benefits. Therefore, she began treatment and they became pregnant. They were both overjoyed. In Maria’s second trimester, the doctor told her that she was carrying quadruplets. The doctor explained about polyembryony and how this was a common occurrence for women who use fertility drugs. At first, Maria did not tell Anthony, and she felt very subversive and guilty about it. A few weeks passed, and she finally told him the news and to her surprise he was overjoyed as he had always wanted a very large family. With his support and her strength, she delivered all the babies and they were all healthy. She suffered a small amount of postpartum depression, but once she began the full-time job of taking care of all her beautiful children when she looked in retrospect at her choices, she was very pleased.

|

Define the prefix per-: |

Define the prefix quad-: |

|

Define the prefix mal-: |

Define the prefix poly-: |

|

Define the prefix omni-: |

Define the prefix sub-: |

|

Define the prefix pre-: |

Define the prefix post-: |

|

Define the prefix tri-: |

Define the prefix retro-: |

Read the paragraph below which contains prefixes from “Roots—Set One.” Afterwards, without using a dictionary give the definition of the italicized words using the context clues. Also give the definition of the root used.

When Jeannine began college, she was convinced that she wanted to become a gynecologist because she was from a family of doctors. However, in class one day as they were looking at a biopsy of infected cells, she felt nauseous. Besides, she never liked her genetics class, so she could now drop this course which was bringing down her G.P.A.. When she told her mother she was changing her major, her mother supported her but warned her not to make such drastic changes habitual. Her mother recommended that she consider instead dermatology because her uncle George who had his own practice enjoyed a good income and complete autonomy. Jeannine, however, said she was done with all medically related fields. She considered the classes she had taken and liked so far. She considered becoming an ethnographer but was not sure if she wanted to take all the required Anthropology classes for that field of work. She had also enjoyed her Marine Biology class but decided it was not for her as she was not very aquatic. Her mother deduced Jeannine’s indecision from her troubled expression and told her not to worry so much because choosing a major much less a career was a very gradual process and that she still had lots of time.

|

Define the root gyn: |

Define the root auto: |

|

Define the root bio: |

Define the root ethno: |

|

Define the root gene: |

Define the root aqua: |

|

Define the root habi: |

Define the root duc: |

|

Define the root derma: |

Define the root grad: |

Read the paragraph below which contains prefixes from “Roots—Set Two.” Afterwards, without using a dictionary give the definition of the italicized words using the context clues. Also give the definition of the root used.

Off in a small, remote village lived a little old inventor. He lived at the edge of town all by himself and had no children, but he was very paternal. He suffered from agoraphobia so instead of going out, he would invite the children of the town into his workshop and teach them about his inventions. One of the children’s favorite inventions was a polyphonic instrument that when contorted could be heard throughout the village. Another favorite was a machine that would record a speaker’s soliloquy and transcribe what he or she said. The inventor even had a painting that changed colors when tactilely triggered and a lamp that produced pyrotechnics when someone sneezed. The adults of the town thought that the inventor was very unorthodox and perhaps a little pathetic for his hermit-like ways, but they respected him…from a distance.

|

Define the root pater: |

Define the root scribe: |

|

Define the root phobia: |

Define the root tact: |

|

Define the root phonic: |

Define the root pyr: |

|

Define the root tort: |

Define the root ortho: |

|

Define the root sol: |

Define the root path: |

Now that you have practiced figuring out words in context, let’s practice creating words in context. In other words, it’s time to put your expanded vocabulary to use and create your own paragraph.

Create words using the following suffixes:

| Suffix: | A word using that suffix: | Suffix: | A word using that suffix: |

|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) –able or –ible |

(6) –arium or –orium |

||

| (2) –age | (7) –hood | ||

| (3) –ant | (8) –less | ||

| (4) –esque | (9) –tude | ||

| (5) –fy | (10) –wise |

Now, create a paragraph (it can be a story, an explanation, a how to, an argument, a description) using the 10 words you created above. The paragraph must make sense as a whole.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________