2.3.4: Model Texts by Studen Authors

- Page ID

- 60218

Model Texts by Student Authors

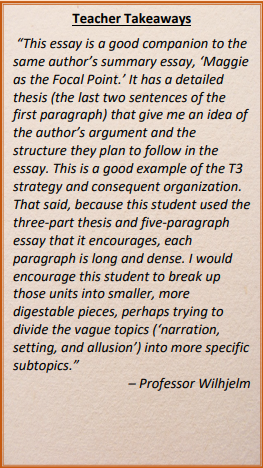

Songs80

(A text wrestling analysis of "Proofs" by Richard Rodriguez)

Songs are culturally important. In the short story "Proofs" by Richard Rodriguez, a young Mexican American man comes to terms with his bi-cultural life. This young man's father came to America from a small and poverty-stricken Mexican village. The young man flashes from his story to his father's story in order to explore his Mexican heritage and American life. Midway through the story Richard Rodriguez utilizes the analogies of songs to represent the cultures and how they differ. Throughout the story there is a clash of cultures. Because culture can be experienced through the arts and teachings of a community, Rodriguez uses the songs of the two cultures to represent the protagonist's bi-cultural experience.

According to Rodriguez, the songs that come from Mexico express an emotional and loving culture and community: "By my mama says there are no songs like the love songs of Mexico" (50). The songs from that culture can be beautiful. It is amazing the love and beauty that come from social capital and community involvement. The language Richard Rodriguez uses to explain these songs is beautiful as well. "-it is the raw edge of sentiment" (51). The author explains how it is the men who keep the songs. No matter how stoic the men are, they have an outlet to express their love and pain as well as every emotion in between. "The cry of a Jackal under the moon, the whistle of a phallus, the maniacal song of the skull" (51). This outlet is an outlet for men to express themselves that is not prevalent in American culture. The songs from the American culture are different. In America the songs get lost. There is assimilation of cultures. The songs of Mexico are important to the protagonist of the story. There is a clash between the old culture in Mexico and the subject's new American life represented in these songs.

A few paragraphs later in the story, on page 52, the author tells us the difference in the American song. America sings a different tune. America is the land of opportunity. It represents upward mobility and the ability to "make it or break it." But it seems there is a cost for all this material gain and all this opportunity. There seems to be a lack of love and emotion, a lack of the ability to express pain and all other feelings, the type of emotion which is expressed in the songs of Mexico. The songs of America say, "You can be anything you want to be" (52). The song represents the American Dream. The cost seems to be the loss of compassion, love, and emotion that is expressed through the songs of Mexico. There is no outlet quite the same for the stoic men of America. Rodriguez explains how the Mexican migrant workers have all that pain and desire, all that emotion penned up inside until it explodes in violent outbursts. "Or they would come into town on Monday nights for the wrestling matches or on Tuesdays for boxing. They worked over in Yolo County. They were men without women. They were Mexicans without Mexico" (49). Rodriguez uses the language in the story almost like a song in order to portray the culture of the American dream. The phrase "I will send for you or I will come home rich," is repeated twice throughout the story. The gain for all this loss of love and compassion is the dream of financial gain. "You have come into the country on your knees with your head down. You are a man" (48). That is the allure of the American Dream.

The protagonist of the story was born in America. Throughout the story he is looking at this illusion of the American Dream through a different frame. He is also trying to come to terms with his own manhood in relation to his American life and Mexican heritage. The subject has the ability to see the two songs in a different light. "The city will win. The city sings mean songs, dirty songs" (52). Part of the subject's reconciliation process with himself is seeing that all the material stuff that is dangled as part of the American Dream is not worth the love and emotion that is held in the old Mexican villages and expressed in their songs.

Rodriguez represents this conflict of culture on page 53. The protagonist of the story is taking pictures during the arrest of illegal border-crossers. "I stare at the faces. They stare at me. To them I am not bearing witness; I am part of the process of being arrested" (53). The subject is torn between the two cultures in a hazy middle ground. He is not one of the migrants and he is not one of the police. He is there taking pictures of the incident with a connection to both of the groups and both of the groups see him connected with the others.

The old Mexican villages are characterized by a lack of: "Mexico is poor" (50). However, this is not the reason for the love and emotion that is held. The thought that people have more love and emotion because they are poor is a misconception. There are both rich people and poor people who have multitudes of love and compassion. The defining elements in creating love and emotion for each other comes from the level of community interaction and trust- the ability to sing these love songs and express emotion towards one another. People who become caught up in the American Dream tend to be obsessed with their own personal gain. This diminishes the social interaction and trust between fellow humans. There is no outlet in the culture of America quite the same as singing love songs towards each other. It does not matter if they are rich or poor, lack of community, trust, and social interaction; lack of songs can lead to lack of love and emotion that is seen in the old songs of Mexico.

The image of the American Dream is bright and shiny. To a young boy in a poor village the thought of power and wealth can dominate over a life of poverty with love and emotion. However, there is poverty in America today as well as in Mexico. The poverty here looks like a little different but many migrants and young men find the American Dream to be an illusion. "Most immigrants to America came from villages. The America that Mexicans find today, at the decline of the century, is a closed-circuit city of ramps and dark towers, a city without God. The city is evil. Turn. Turn" (50). The song of America sings an inviting tune for young men from poor villages. When they arrive though it is not what they dreamed about. The subject of the story can see this. He is trying to come of age in his own way, acknowledging America and the Mexico of old. He is able to look back and forth in relation to the America his father came to for power and wealth and the America that he grew up in. All the while, he watches this migration of poor villages, filled with love and emotion, to a big heartless city, while referring back to his father's memory of why he came to America and his own memories of growing up in America. "Like wandering Jews. They carried their home with them, back and forth: they had no true home but the tabernacle of memory" (51). The subject of the story is experiencing all of this conflict of culture and trying to compose his own song.

Works Cited

Rodriguez, Richard. "Proofs." In Short: A Collection of Brief Creative Nonfiction, edited by Judith Kitchen and Mary Paumier Jones, Norton, 1996, pp. 48-54.

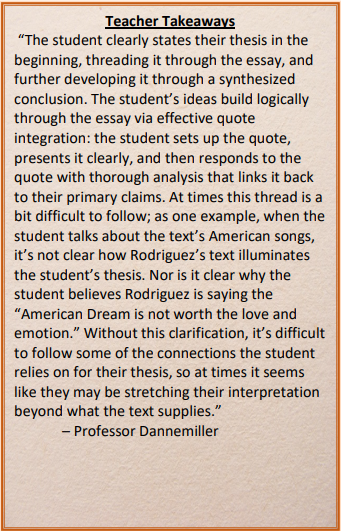

Normal Person: An Analysis of the Standards of Normativity in "A Plague of Tics"81

David Sedaris' essay "A Plague of Tics" describes the Sedaris' psychological struggles he encountered in his youth, expressed through obsessive-compulsive tics. These abnormal behaviors heavily inhibited his functionings, but more importantly, isolated and embarrassed him during his childhood, adolescence, and young adult years. Authority figures in his life would mock him openly, and he constantly struggled to perform routine simple tasks in a timely manner, solely due to the amount of time that needed to be set aside for carrying out these compulsive tics. He lacked the necessary social support an adolescent requires because of his apparent abnormality. But when we look at the behaviors of his parents, as well as the socially acceptable tics of our society more generally, we see how Sedaris' tics are in fact not too different, if not less harmful than those of the society around him. By exploring Sedaris' isolation, we can discover that socially constructed standards of normativity are at best arbitrary, and at worst violent.

As a young boy, Sedaris is initially completely unaware that his tics are not socially acceptable in the outside world. He is puzzled when his teacher, Miss Chestnut, correctly guesses that he is "going to hit [himself] over the head with [his] shoe" (361), despite the obvious removal of his shoe during their private meeting. Miss Chestnut continues by embarrassingly making fun out of the fact that Sedaris' cannot help but "bathe her light switch with [his] germ-ridden tongue" (361) repeatedly throughout the school day. She targets Sedaris with mocking questions, putting him on the spot in front of his class; this behavior is not ethical due to Sedaris' age. It violates the trust that students should have in their teachers and other caregivers. Miss Chestnut criticizes him excessively for his ambiguous, child-like answers. For example, she drills him on whether it is "healthy to hit ourselves over the head with our shoes" (361) and he "guess[es] that it was not," (361) as a child might praise it. She ridicules his use of the term "guess," using obvious examples of instances when guessing would not be appropriate, such as "[running] into traffic with a paper sack over [her] head" (361). Her mockery is not only rude, but ableist and unethical. Any teacher- at least nowadays- should recognize that Sedaris needs compassion and support, not emotional abuse.

These kinds of negative responses to Sedaris' behavior continue upon his return home, in which the role of the insensitive authority figure is taken on by his mother. In a time when maternal support is crucial for a secure and confident upbringing, Sedaris' mother was never understanding of his behavior, and left little room for open, honest discussion regarding ways to cope with his compulsiveness. She reacted harshly to the letter sent home by Miss Chestnut, nailing Sedaris, exclaiming that his "goddamned math teacher" (363) noticed his strange behaviors, as if it should have been obvious to young, egocentric Sedaris. When teachers like Miss Chestnut meet with her to discuss young David's problems, she makes fun of him, imitating his compulsions; Sedaris is struck by "a sharp, stinging sense of recognition" upon viewing this mockery (365). Sedaris' mother, too, is an authority figure who maintains ableist standards of normativity by taunting her own son. Meeting with teachers should be an opportunity to truly help David, not tease him.

On the day that Miss Chestnut makes her appearance in the Sedaris household to discuss his behaviors with his mother, Sedaris watches them from the staircase, helplessly embarrassed. We can infer from this scene that Sedaris has actually become aware of that fact that his tics are not considered to be socially acceptable, and that he must be "the wierd kid" among his peers- and even to his parents and teachers. his mother's cavalier derision demonstrates her apparent disinterest in the well-being of he son, as she blatantly brushes off his strange behaviors except in the instance during which she can put them on display for the purpose of entertaining a crowd. What all of these pieces of his mother's flawed personality show us is that she has issues too- drinking and smoking, in addition to her poor mothering- but yet Sedaris is the one being chastised while she lives a normal life. Later in the essay, Sedaris describes how "a blow to the nose can be positively narcotic" (366), drawing a parallel to his mother's drinking and smoking. From this comparison, we can begin to see flawed standards of "normal behavior": although many people drink and smoke (especially at the time the story takes place), these habits are much more harmful than what Sedaris does in private.

Sedaris' father has an equally harmful personality, but it manifests differently. Sedaris describes him as a hoarder, one who has, "saved it all: every last Green Stamp and coupon, every outgrown bathing suit and scrap of linoleum" (365). Sedaris' father attempts to "cure [Sedaris] with a series of threats" (366). In one scene, he even enacts violence upon David by slamming on the brakes of the car while David has his nose pressed against a windshield. Sedaris reminds us that his behavior might have been unusual, but it wasn't violent: "So what if I wanted to touch my nose to the windshield? Who was I hurting?" (366). In fact, it is in that very scene that Sedaris draws the aforementioned parallel to his mother's drinking: when Sedaris discovers that "a blow to the nose can be positively narcotic," it is while his father is driving around "with a lapful of rejected, out-of-state coupons" (366). Not only is Sedaris' father violating the trust David places in him as a caregiver; his hoarding is an arguably unhealthy habit that simply happens to be more socially acceptable than licking a concrete toadstool. Comparing Sedaris's tics to his father's issues, it is apparent that his father's are much more harmful than his own. None of the adults in Sedaris' life are innocent-"mother smokes and Miss Chestnut massaged her waist twenty, thirty times a day- and here I couldn't press my nose against the windshield of a car" (366)- but nevertheless, Sedaris's problems are ridiculed or ignored by the 'normal' people in his life, again bringing into question what it means to be a normal person.

In high school, Sedaris' begins to take certain measures to actively control and hide his socially unacceptable behaviors. "For a time," he says, "I thought that if I accompanied my habits with an outlandish wardrobe, I might be viewed as eccentric rather than just plain retarded" (369). Upon this notion, Sedaris starts to hang numerous medallions around his neck, reflecting that he "might as well have worn a cowbell" (369) due to the obvious noises they made when he would jerk his head violently, drawing more attention to his behaviors (the opposite of the desired effect). He also wore large glasses, which he now realizes made it easier to observe his habit of rolling his eyes into his head, and "clunky platform shoes [that] left lumps when used to discreetly tap [his] foreground" (369). Clearly Sedaris was trying to appear more normal, in a sense, but was failing terribly. After high school, Sedairs faces the new wrinkle of sharing a college dorm room. He conjures up elaborate excuses to hide specific tics, ensuring his roommate that "there's a good chance the brain tumor will shrink" (369) if he shakes his head around hard enough and that specialists have ordered him to perform "eye exercises to strengthen what they call he 'corneal fibers'" (369). He eventually comes to a point of such paranoid hypervigilance that he memorizes his roommate's class schedule to find moments to carry his tics in privacy. Sedaris worries himself sick attempting to approximate 'normal': "I got exactly fourteen minutes of sleep during my entire first year of college" (369). When people are pressured to perform an identity inconsistent with their own-pressured by socially constructed standards of normativity- they harm themselves in the process. Furthermore, even though the responsibility does not necessarily fall on Sedaris' peers to offer support, we can assume that their condemnation of his behavior reinforces the standards that oppress him.

Sedaris' compulsive habits peak and begin their slow decline when he picks up the new habit of smoking cigarettes, which is of course much more socially acceptable while just as compulsive in nature once addiction has the chance to take over. He reflects, from the standpoint of an adult, on the reason for the acquired habit, speculating that "maybe it was coincidental, or perhaps ... much more socially acceptable than crying out in tiny voices" (371). He is calmed by smoking, saying that "everything's fine as long I know there's a cigarette in my immediate future" (372). (Remarkably, he also reveals that he has not truly been cured, as he revisits his former ticks and will "dare to press [his] nose against the doorknob or roll his eyes to achieve that once-satisfying ache" [372.]) Sedaris has officially achieved the tiresome goal of appearing 'normal', as his compulsive tics seemed to "[fade] out by the time [he] took up with cigarettes" (371). It is important to realize, however, that Sedaris might have found a socially acceptable way to mask his tics, but not a healthy one. The fact that the only activity that could take place of his compulsive tendencies was the dangerous use of a highly addictive substance, one that has proven to be dangerously harmful with frequent and prolonged use, shows that he is conforming to the standards of society which do not correspond with healthy behaviors.

In a society full of dangerous, inconvenient, or downright strange habits that are nevertheless considered socially acceptable, David Sedaris suffered through the psychic and physical violence and negligence of those who should have cared for him, With what we can clearly recognize as a socially constructed disability, Sedaris was continually denied support and mocked by authority figures. He struggled to socialize and perform academically while still carrying out each task he was innately compelled to do, and faced consistent social hardship because of his outlandish appearance and behaviors that are viewed in our society as "weird." Because of ableist, socially constructed standards of normativity, Sedaris had to face a long string of turmoil and worry taht most of society may never come to completely understand. We can only hope that as a greater society, we continue sharing and studying stories like Sedairs' so that we critique the flawed guidelines we force upon different bodies and minds, and attempt to be more accepting and welcoming of the idiosyncrasies we might deem to be unfavorable.

Works Cited

Sedaris, David. "A Plague of Tics." 50 Essays: A Portable Anthology, 4th edition, edited by Samuel Cohen, Bedford, 2013, pp. 359-372.

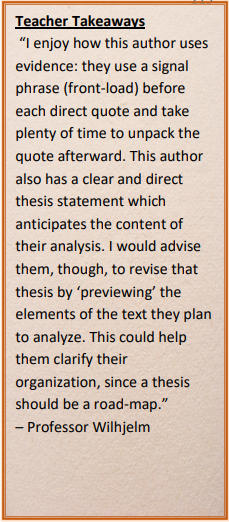

Analyzing "Richard Cory"82

In the poem "Richard Cory" by Edward Arlington Robinson, a narrative is told about the character Richard Cory by those who admired him. In the last stanza, the narrator, who uses the pronoun "we," tells use that Richard Cory commits suicide. Throughout most of the poem, though, Cory had been described as a wealthy gentleman. The "people on the pavement" (2), the speakers of the poem, admired him because he presented himself well, was educated, and was wealthy. The poem presents the idea that, even though Cory seemed to have everything going for him, being wealthy does not guarantee happiness or health.

Throughout the first three stanzas Cory is described in a positive light, which makes it seem like he has everything that he could ever need. Specifically, the speaker compares Cory directly and indirectly to royalty because of his wealth and his physical appearance: "He was a gentleman from sole to crown, / Clean favored and imperially slim" (Robinson 3-4). In line 3, the speaker is punning on "soul" and "crown." At the same time, Cory is both a gentleman from foot (sole) to head (crown) and also soul to crown. The use of the word "crown" instead of head is a clever way to show that Richard was thought of as a king to the community. The phrase "imperially slim" can also be associated with royalty because imperial comes from "empire." The descriptions used gave clear insight that he was admired for his appearance and manners, like a king or emperor.

In other parts of the poem, we see that Cory is 'above' the speakers. The first lines, "When Richard Cory went down torn, / We people on the pavement looked at him" (1-2), show that Cory is not from the same place as the speakers. The words "down" and "pavement" also suggest a difference in status between Cory and the people. The phrase "We people on the pavement" used in the first stanza (Robinson 2), tells us that the narrator and those that they are including in their "we" may be homeless and sleeping on the pavement; at the least, this phrase shows that "we" are below Cory.

In addition to being 'above,' Cory is also isolated from the speakers. In the second stanza, we can see that there was little interaction between Cory and the people on the pavement: "And he was always human when he talked; / But still fluttered pulses when he said, / 'Good- morning'" (Robinson 6-8). Because people are "still fluttered" by so little, we can speculate that it was special for them to talk to Cory. But these interactions gave those on the pavement no insight into Richard's real feelings or personality. Directly after the descriptions of the impersonal interactions, the narrator mentions that "he was rich-yes, richer than a king" (Robinson 9). At the same time that Cory is again compared to royalty, this line reveals that people were focused on his wealth and outward appearance, not his personal life or wellbeing.

The use of the first-person plural narration to describe Cory gives the reader the impression that everyone in Cory's presence longed to have the life that he did. Using "we," the narrator speaks for many people at once. From the end of the third stanza to the end of the poem, the writing turns from admirable description of Richard to a noticeably more melancholy, dreary description of what those who admired Richard had to do because they did not have all that Richard did. These people had nothing, but they thought that he was everything. To make us wish that we were in his place. So on we worked, and waited for the light,

And went without the meat, and cursed the bread... (Robinson 9-12) They sacrificed their personal lives and food to try to rise up to Cory's level. They longed to not be required to struggle. A heavy focus on money and materialistic things blocked their ability to see what Richard Cory was actually feeling or going through. I suggest that "we" also includes the reader of the poem. If we read the poem this way, "Richard Cory" critiques the way we glorify wealthy people's lives to the point that we hurt ourselves. Our society values financial success over mental health and believes in a false narrative about social mobility.

Though the piece was written more than a century ago, the perceived message has not been lost. Money and materialistic things do not create happiness, only admiration and alienation from those around you. Therefore, we should not sacrifice our own happiness and leisure for a lifestyle that might not make us happy. The poem's messages speaks to our modern society, too, because it shows a stigma surrounding mental health: if people have "everything / To make us wish that we were in [their] place" (11-12), we often assume that they don't deal with the same mental health struggles as everyone. "Richard Cory" reminds us that we should take care of each other, not assume that people are okay because they put up a good front.

Works Cited

Robinson, Edward Arlington. "Richard Cory." The Norton Introduction to Literature, Shorter 12th edition, edited by Kelly J. Mays, Norton, 2017, p.482.

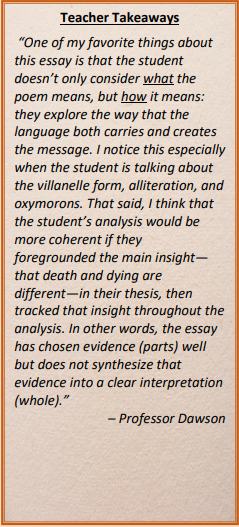

To Suffer or Surrender? An Analysis of Dylan Thomas's "Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night" 83

Death is a part of life that everyone must face at one point or another. The poem "Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night" depicts the grief and panic one feels when a loved is approaching the end of their life, while presenting a question; is it right to surrender to death, or should it be resisted? In this poem, Dylan Thomas opposses the idea of a peaceful passing, and uses various literary devices such as repetition, metaphor, and imagery to argue that death should be resisted at all costs.

The first thing that one may notice while reading Thomas's piece is that there are key phrases repeated throughout the poem. As a result of the poem's villanelle structure, both lines "Do not go gentle into that good night" and "Rage, rage against the dying of the light" (Thomas) are repeated often. This repetition gives the reader a sense of panic and desperation as the speaker pleads with their father to stay. The first line showcases a bit of alliteration of n sounds at the beginning of "not" and "night," as well as alliteration of hard g sounds in the words "go" and "good." These lines are vital to the poem as they reiterate its central meaning, making it far from subtle and extremely hard to miss. These lines add even more significance due to their placement in the poem. "Dying of the light" and "good night" are direct metaphors for death, and with the exception of the first line of the poem, they only appear at the end of a stanza. This structural choice is a result of the villanelle form, but we can interpret it to highlight the predictability of life itself, and signifies the undeniable and unavoidable fact that everyone must face death at the end of one's life. The line "my father, there on the sad height" (Thomas 16) confirms that this poem is directed to the speaker's father, the idea presented in these lines is what Thomas wants his father to recognize above all else.

This poem also has many contradictions. In the fifth stanza, Thomas describes men near death "who see with blinding sight" (Thomas 13). "Blinding sight" is an oxymoron, which implies that although with age most men lose their sight, they are wiser and enlightened, and have a greater understanding of the world. In this poem "night" is synonymous with "death"; thus, the phrase "good night" can also be considered an oxymoron if one does not consider death good. Presumably the speaker does not, given their desperation for their father to avoid it. The use of the word "good" initially seems odd, however, although it may seem like the speaker rejects the idea of death itself, this is not entirely the case. Thomas presents yet another oxymoron by saying "Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears" (Thomas 17). By referring to passionate tears as a blessing and a curse, which insinuates that the speaker does not necessarily believe death itself is inherently wrong, but to remain complicit in the face of death would be. These tears would be a curse because it is difficult to watch a loved one cry, but a blessing because the tears are a sign that the father is unwilling to surrender to death. This line is especially significant as it distinguishes the author's beliefs about death versus dying, which are vastly different. "Good night" is an acknowledgement of the bittersweet relief of the struggles and hardships of life that come with death, while "fierce tears" and the repeated line "Rage, rage against the dying of the light" show that the speaker sees the act of dying as a much more passionate, sad, and angering experience. The presence of these oxymorons creates a sense of conflict in the reader, a feeling that is often felt by those who are struggling to say goodbye to a loved one.

At the beginning of the middle four stanzas they each begin with a description of a man, "Wise men... Good men... Wild men... Grave men..." (Thomas 4; 7; 10; 13). Each of these men have one characteristic that is shared, which is that they all fought against death for as long as they could. These examples are perhaps used in an attempt to inspire the father. Although the speaker begs their father to "rage" against death, this is not to say that they believe death is avoidable. Thomas reveals this in the 2nd stanza that "wise men at their end know dark is right" (Thomas 4), meaning that wise men know that death is inevitable, which in return means that the speaker is conscious of this fact as well. It also refers to the dark as "right", which may seem contradicting to the notion presented that death should not be surrendered to; however, this is yet another example of the contrast between the author's beliefs about death itself, and the act of dying. The last perspective that Thomas shows is "Grave men". Of course, the wordplay of "grave" alludes to death. Moreover, similarly to the second stanza that referred to "wise men", this characterization of "grave men" alludes to the speaker's knowledge of impending doom, despite the constant pleads for their father to resist it.

Another common theme that occurs in the stanzas about these men is regret. A large reason the speaker is so insistent that his father does not surrender to the "dying of the light" is because the speaker does not want their father to die with regrets, and believes that any honorable man should do everything they can in their power to make a positive impact in the world. Thomas makes it clear that it is cowardly to surrender when one can still do good, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant.

All these examples of men are positively associated with the "rage" that Thomas so often refers to, further supporting the idea that rage, passion, and madness are qualities of honorable men. Throughout stanza 2, 3, 4 and 5, the author paints pictures of these men dancing, singing in the sun, and blazing like meteors. Despite the dark and dismal tone of the piece, the imagery used depicts life as joyous and lively. However, a juxtaposition still exists between men who are truly living, and men who are simply avoiding death. Words like burn, rave, sad, and rage are used when referencing the prime of one's life. None of these words give the feeling of peace; however those alluding to life are far more cheerful. Although the author rarely uses the words "life" and "death", the text symbolizes them through light and night. The contrast between the authors interpretation of life versus death is drastically different. Thomas wants the reader to see that no matter how old they become, there is always something to strive for and fight for, and to accept death would be to deprive the world of what you have to offer.

In this poem Dylan Thomas juggles the complicated concept of mortality. Thomas perfectly portrays the fight against time as we age, as well as the fear and desperation that many often feel when facing the loss of a loved one. Although the fight against death cannot be won, in "Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night" Dylan Thomas emphasizes how despite this indisputable fact, one should still fight against death with all their might. Through the use of literary devices such as oxymorons and repetition, Thomas inspires readers to persevere, even in the most dire circumstances.

Works Cited

Thomas, Dylan. "Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night." The Norton Introduction to Literature, edited by Kelly J. Mays, portable 12th ed., W. W. Norton & Company, 2015, pp. 659

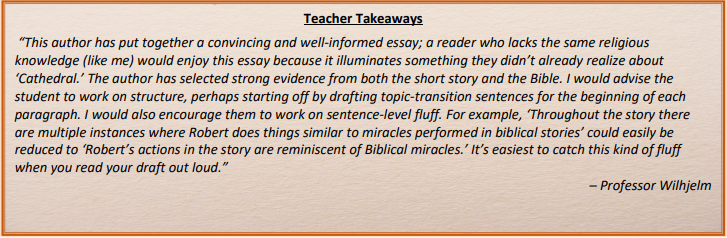

Christ Like 84

in Raymond Carver's "Cathedral", the character Robert plays a Christ-like role. To mirror that, the narrator plays the role of Saul, a man who despised and attacked Christ and his followers until he became converted. Throughout the story there are multiple instances where Robert does things similar to miracles performed in biblical stories, and the narrator continues to doubt and judge him. Despite Robert making efforts to converse with the narrator, he refuses to look past the oddity of his blindness. The author also pays close attention to eyes and blindness. To quote the Bible, "Having eyes, see ye not?" (King James Bible, Mark, 8. 18). The characters who have sight don't see as much as Robert, and he is able to open their eyes and hearts.

When Robert is first brought up, it is as a story. The narrator has heard of him and how wonderful he is, but has strong doubts about the legitimacy of it all. He shares a specific instance in which Robert asked to touch his wife's face. He says, "She told me he touched his fingers to every part of her face, her nose- even her neck!", and goes on to talk about how she tried to write a poem about it (Carver 34). The experience mentioned resembled the story of Jesus healing a blind man by putting his hands on his eyes and how, afterward, the man was restored (Mark 8.21-26). While sharing the story, however, the only thing the narrator cares about is that the blind man touched his wife's neck. At this point in the story the narrator still only cares about what's right in front of him, so hearing retellings means nothing to him.

When Saul is introduced in the Bible, it is as a man who spent his time persecuting the followers of Christ and "made havoc of the church" (Acts 8.3-5). From the very beginning of the story, the narrator makes it known that, "A blind man in my house was not something that I looked forward to" (Carver 34). He can't stand the idea of something he'd only seen in movies and heard tell of becoming something real. Even when talking about his own wife, he disregards the poem she wrote for him. When he hears the name of Robert's deceased wife, his first response is to point out how strange it sounds (Carver 36). He despises Robert, so he takes out his aggression on the people who don't, and drives them away.

The narrator's wife drives to the train station to pick up Robert while he stays home and waits, blaming Robert for his boredom. When they finally do arrive, the first thing he notices about Robert is his beard. It might be a stretch to call this a biblical parallel since a lot of people have beards, but Carver makes a big deal out of this detail. The next thing the narrator points out, though, is that his wife "had this blind man by his coat sleeve" (Carver 37). This draws the parallel to another biblical story. In this story a woman who has been suffering from a disease sees Jesus and says to herself, "If I may but touch his garment I shall be whole" (Matt. 9.21). Before they had gotten in the house the narrator's wife had Robert by the arm, but even after they were at the front porch, she still wanted to hold onto his sleeve.

The narrator continues to make observations about Robert when he first sees him. One that stood out was when he was talking more about Robert's physically, saying he had "stooped shoulder, as if he carried a great weight there" (Carver 38). There are many instances in the Bible where Jesus is depicted carrying some type of heavy burden, like a lost sheep, the sins of the world, and even his own cross. He also points out on multiple occasions that Robert has a big and booming voice, which resembles a lot of depictions of a voice "from on high."

After they sit and talk for a while, they have dinner. This dinner resembles the last supper, especially when the narrator says, "We ate like there was no tomorrow" (Carver 39). He also describes how Robert eats and says "he'd tear of a hunk of buttered bread and eat that. He'd follow this up with a big drink of milk" (Carver 39). Those aren't the only things he ate, but the order in which he ate the bread and took a drink is the same order as the sacrament, a ritual created at the last supper. The author writing it in that order, despite it being irrelevant to the story, is another parallel that seems oddly specific in an otherwise normal sequence of events. What happens after the dinner follows the progression of the Bible as well.

After they've eaten a meal like it was their last the narrator's wife falls asleep like Jesus' apostles outside the garden of Gethsemane. In the Bible, the garden of Gethsemane is where Jesus goes after creating the sacrament and takes on the sins of all the world. He tells his apostles to keep watch outside the garden, but they fall asleep and leave him to be captured by the non-believers (Matt. 26.36-40). In "Cathedral," Robert is left high and alone with the narrator when the woman who holds him in such high regard falls asleep. Instead of being taken prisoner, however, Robert turns the tables and puts all focus on the narrator. His talking to the narrator is like a metaphorical taking on of his sins. On page 46 the narrator tries to explain to him what a cathedral looks like. It turns out to be of no use, since the narrator has never talked to a blind person before, much like a person trying to pray who never has before. Robert decides he needs to place his hands on the narrator like he did to his wife on the first page.

When Saul becomes converted, it is when Jesus speaks to him as a voice "from on high." As soon as the narrator begins drawing with Robert (a man who is high), his eyes open up. When Jesus speaks to Saul, he can no longer see. During the drawing of the cathedral, Robert asks the narrator to close his eyes. Even when Robert tells him he can open his eyes, the narrator decides to keep them closed. He went from thinking Robert coming over was a stupid idea to being a full believer in him. He says, "I put in windows with arches. I drew flying buttresses. I hung great doors. I couldn't stop" (Carver 45). Even with all the harsh things the narrator said about Robert, being touched by him and made his heart open up. Carver ends the story after the cathedral has been drawn and has the narrator say, "It's really something" (Carver 46).

Robert acts as a miracle worker, not only to the narrator's wife, but to him as well. Despite the difficult personality, the narrator can't help but be converted. He says how resistant he is to have him over, and tries to avoid any conversation with him. He pokes fun at little details about him, disregards peoples' love for him, but still can't help being converted by him. Robert's booming voice carries power over the narrator, but his soft touch is what finally makes him see.

Works Cited

Carver, Raymond. "Cathedral." The Norton Introduction to Literature, Portable 12th edition, edited by Kelly J. Mays, Norton, 2017, pp. 33-46.

The Bible. Authorized King James Version, Oxford UP, 1978.

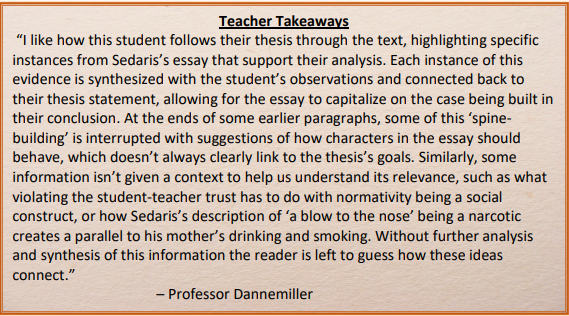

The Space Between the Racial Binary 85

Toni Morrison in "Recitatif" confronts race as a social construction, where race is not biological but created from human interactions. Morrison does not disclose the race of the two main characters, Twyla and Roberta, although she does provide that one character is black and the other character is white. Morrison emphasizes intersectionality by confounding stereotypes about race through narration, setting, and allusion. We have been trained to 'read' race through a variety of signifers, but "Recitatif" puts those signifers at odds.

Twyla is the narrator throughout "Recitatif" where she describes the events from her own point of view. Since the story is from Twyla's perspective, it allows the readers to characterize her and Roberta solely based on what she mentions. At the beginning of the story Twyla states that "[her] mother danced all night", which is the main reason why Twyla is "taken to St. Bonny's" (Morrison 139). Twyla soon finds that she will be "stuck... with a girl from a while other race" who "never washed [her] hair and [she] smelled funny" (Morrison 139). From Twyla's description of Roberta's hair and scent, one could assume that Roberta is black due to the stereotype revolves around a black individual's hair. Later on in the story Twyla runs into Roberta at her work and describes Roberta's hair as "so big and wild" the "[she] coul hardly see her face", which is another indicator that Roberta has Afro-textured hair (Morrison 144). Yet, when Twyla encounters Roberta at a grocery store "her huge hair was sleek" and "smooth" resembling a white woman's hair style (Morrison 146). Roberta's hairstyles are stereotypes that conflict with one another; one attributing to a black woman, the other to a white woman. The differences in hair texture, and style, are a result of phenotypes, not race. Phenotypes are observable traits that "result from interactions between your genes and the environment" ("What are Phenotypes?"). There is not a specific gene in the human genome that can be used to determine a person's race. Therefore, the racial catergories in society are not constructed on the genetic level, but the social. Dr. J Craig Venter states, "We all evolved in the last 100,000 years from the same small number of tribes that migrated out of Africa and colonized the world", so it does not make sense to claim that race has evolved a specific gene and certain people inherit those specific genes (Angier). From Twyla's narration of Roberta, Roberta can be classified into one of two racial groups based on the stereotypes ascribed to her.

Intersectionality states that people are at a disadvantage by multiple sources of oppressions, such their race and class. "Recitatif" seems to be written during the Civil Rights Era where protests against racial integration took place. This is made evident when Twyla says, "strife came to us that fall... Strife. Racial strife" (Morrison 150). According to NPR, the Supreme Court ordered school busing in 1969 and went into effect in 1973 to allow for desegregation ("Legacy"). Twyla "thought it was a good thing until she heard it was a bad thing", while Roberta picketed outside "the school they were trying to integrate" (Morrison 150). Twyla and Roberta both become irritated with one another's reaction to the school busing order, but what woman is on which side? Roberta seems to be a white woman against integrating black students into her children's school, and Twyla suggests that she is a black mother who simply wants best for her son Joesph even if that does mean going to a school that is "far-out-of-the-way" (Morrison 150). At this point in the story Roberta lives in "Annandale" which is "a neighborhood full of doctors and IBM executives" (Morrison 147), and at the same time, Twyla is "Mrs. Benson" living in "Newburgh" where "half the population... is on welfare..." (Morrison 145). Twyla implies that Newburgh is being gentrified by these "smart IBM people", which inevitably results in an increase in rent and property values, as well as changes the area's culture. In America, minorities are usually the individuals who are displaced and taken over by wealthier, middle-class white individuals who are displaced and taken over by wealthier, middle-class white individuals. From Twyla's tone, and the setting, it seems that Twyla is a black individual that is angry towards "the rich IBM crowd" (Morrison 146). When Twyla and Roberta are bickering over school busing, Roberta claims that America "is a free country" and she is not "doing anything" to Twyla (Morrison 150). From Roberta's statements, it suggests that she is a affluent, and ignorant white person that is oblivious to the hardships that African Americans had to overcome, and still face today. Rhonda Soto contends that "Discussing race without including class analysis is like watching a bird fly without looking at the sky...". It is ingrained in America as the normative that whites are mostly part of the middle-class and upper-class, while blacks are part of the working-class. Black individuals are being classified as low-income based entirely on their skin color. It is pronounced that Twyla is being discriminated against because she is a black woman, living in a low-income neighborhood where she lacks basic resources. For example. when Twyla and Roberta become hostile with one another over school busing, the supposedly white mothers start moving towards Twyla's car to harass her. She points out that "[my] face [] looked mean to them" and that these mothers "could not wait to throw themselves in front of a police car" (Morrison 151). Twyla is indicating that these mothers are priviliged based on their skin color, while she had to wait until her car started to rock back and forth to a point where "the four policeman who had been drinking Tab in their car finally got the message and [then] strolled over" (Morrison 151). This shows that Roberta and the mothers protesting are white, while Twyla is a black woman fighting for her resources. Not only is Twyla being targeted due to her race, but as well her class by protesting mothers who have classified her based on intersectionality.

Intersectionality is also alluded in "Recitatif" based on Roberta's interests. Twyla confronts Roberta at the "Howard Johnson's" while working as a waitress with her "blue and white triangle on [her] head" and "[her] hair shapeless in a net" (Morrison 145). Roberta boasts that her friend has "an appointment with Hendrix" and shames Twyla for not knowing Jimi Hendrix (Morrison 145). Roberta begins to explain that "he's only the biggest" rockstar, guitarist, or whatever Roberta was going to say. It is clear that Roberta is infatuated with Jimi Hendrix, who was an African American rock guitarist. Because Jimi Hendrix is a black musician, the reader could also assume that Roberta is also black. At the same time, Roberta may be white since Jimi Hendrix appealed to a plethora of people. In addition, Twyla illustrates when she saw Roberta "sitting in [the] booth" she was "with two guys smothered in head and facial" (Morrison 144). These men may be two white counter culturists, and possible polygamists, in a relationship with Roberta who is also white. From Roberta's enthusiasm in Jimi Hendrix it alludes that she may be black or white, and categorized from this interest.

Intersectionality states that people are prone to "predict an individual's identity, beliefs, or values based on categories like race" (Williams). Morrison chose not to disclose the race of Twyla and Roberta to allow the reader to make conclusions about the two women based on the vague stereotypes Morrison presented throughout "Recitatif". Narration, setting, and allusion helped make intersectionality apparent, which in turn allowed the readers understand, or see, that race is in fact a social construction. "Recitatif" forces the readers to come to terms with their own racial prejudices.

Works Cited

Angier, Natalie. "Do Races Differ? Not Really, DNA Shows." The New York Times, 22 Aug. 2000, http://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/national/science/082200sci-genetics-race.html

Morrison, Toni. "Recitatif." The Norton Introduction to Literature. Portable 12th edition, edited by Kelly J. Mays, W. W. Norton & Company, 2017, pp. 483+.

"The Legacy of School Busing." NPR, 30 Apr. 2004, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1853532

Soto, Rhonda. "Race and Class: Taking Action at the Intersections." Association of American Colleges & Universities, 1 June 2015, http://www.aacu.org/diversitydemocracy/2008/fall/soto

Williams, Steve. "What is Intersectionality, and Why Is It Important?" Care2, http://www.care2.com/causes/what-is-intersectionality.html

"What Are Phenotypes?" 23andMe, http://www.23andme.com/gen101/phenotype/