9.1: Style

- Page ID

- 25421

What is style?

The content of your mind is what you are telling. Style is how you tell it. In other words, style is the way you tell what is in your mind. Style has to do with things like sound and rhythm, word choice, where you place words and phrases in sentences, and sentence length and structure. You want to have a style that is going to get and keep your audience. Style and tone are closely related. Here we especially review style.

Style and clarity

Writing assumes an audience and audiences must understand a person's writing. Thus, before you ever think about style, you need to make sure you are clear so your audience understands what your thought is. To have clear writing, you must have clear thinking. People who write a great deal still struggle with getting their thoughts onto the page, and you must wrestle with this too. Take heart. You’re not alone, as the philosopher Wittgenstein wrote

Everything that can be thought at all can be thought clearly (28).

You could replace “thought” here with “written.”

Once your basic ideas are on the paper and clear, and your organization and research are pretty good, then you can move on to think about style. It's something that often comes out without thinking about it. So, in considering your style, you have to work your brain hard to think about how you are coming across in your writing and whether or not your style helps or takes away from your main ideas. You do all this by considering your audience.

You can have a wonderful and captivating style, but it does you no good if you are not communicating to your audience. Write plainly, and not in parables, or you will probably confuse your audience. Sometimes you are trying to be vague, or abstract, or to “speak enigmas” as Stevenson wrote in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (40), but you should not be writing enigmas unintentionally.

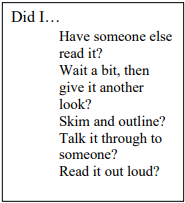

Ensuring clarity

You must have a clear style. One of the most common ways to make sure your writing is clear is to have someone else read it and tell you whether or not they understand it. Another way is for you to write something, and then set it aside. A few days later, you can take a “fresh” look at it and see it as if with new eyes, and ask: “Is it clear?” Another way to check for clarity is to skim through your writing quickly, outlining your main ideas on a separate piece of paper. Then look at what you have in your outline— is this essentially what you wanted to say? Another way is to simply pick up a conversation with someone. Tell them, “I’m writing a paper on forests.” Then go on, “My main point is that…” Are you able to simply and easily explain the contents of your paper? A final way to check your paper for clarity is to read it out loud to yourself, sometimes in front of a mirror. As you read, are you following what is said? What do you hear?

Consistency

Besides being clear, you must be consistent. Imagine walking up a flight of stairs. Each step is a different distance from the next one. In such a situation, you will spend most of your time trying to figure out where to put your foot most safely, rather than getting to the top of the landing quickly, where the leprechaun and the pot of gold are. This disorienting effect is what you do to your audience when you are not consistent in your writing.

Your natural style

Style is the way in which you say what you say, as we mentioned above. It is not the what, but the how. You should choose what comes naturally as your default style. Aristotle wrote that “That which is natural persuades, but the artificial does not” (353). You should try not to be artificial when you write—it should “sound like you” instead of sounding like someone who is trying to do or be something they are not. However, you still need to consider audience. For example, you would not want to write like your average talking self, texting an audience of close friends late at night, if you are writing to the Executive Director of a non-profit.

Slowly, over time, as you learn more about writing, and write more and more, your style will probably change. You will incorporate aspects of different styles of the different authors you have read into your own style as you hone your writing process. You will also be able to write in different styles. But now, as you begin writing longer pieces, you should start by simply doing what first comes to your mind.

For example, say you want to write a description about last night. So you, almost unthinkingly, begin,

Last night I saw a lady in pink.

That is your first sentence. You look at it and try to decide if that is how you want to start. At this point, you might become self-conscious. You think: that’s too simple and childish. So you change it to

Last night I beheld a damsel in pink.

But notice that this was not what came to your mind first, and also notice that most people don’t use the word “damsel” any longer, nor the word “beheld.” Therefore, hold off on trying to “elevate” your language until it comes naturally to you.

For another example, say you are writing a description about last night again. Now perhaps you would like to allude to Coleridge’s poem “Kubla Khan” where there is a line,

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw

Perhaps you want to allude to this poem because you want to make the point in your writing that this is not just a description about last night, but a commentary on inspiration. Then you could write,

Last night I beheld a damsel in pink. She held a harp.

That would fit your subject matter, it would be intentional, and it would probably please your audience, depending on who they are.

To take another example, what if you were writing an eye-witness report, as if for a school newspaper, about attending a legislative meeting on recycling? Would you start,

The pained faces of the sign-waving students faced the passive bowed heads of their local legislators at the meeting last Friday about recycling funding…

Or would you start,

Mr. Smith and Ms. Haran, state legislators, met with students at the Capitol for a few hours on Friday to discuss the upcoming vote on recycling funding…

At least one way to answer this question is to ask: Which of these styles sounds more natural to me? In deciding this, of course, you must always think of audience.

Audience drives style

As they go through whatever writing process they have, writers adjust their style to their audiences to avoid odd turns of phrases, elaborate sentences, and exotic images unless the audience needs them for a specific purpose. In other words, don’t be dull, and don’t be odd, and don’t be vague or wandering, unless this is your intent and you know your audience requires it.

Imagine you are asked to write an argument research paper. You have done your research and have a rough outline of how you are going to organize the paper. Now you are ready to sit down and write. What style will you use? The style of argument is often clinical; it is very plain, straightforward, and logical. In other words, the language, or style, of an argument paper is sometimes uncomplicated, unadorned and clear, and straightforward. Even anecdotes given to start or illustrate a point are quite easy to understand. We do not doll up argument research papers with amazing feats of poetry or stunning images, for the most part.

Not only argument papers, but expository (informative) writing papers are also often very simple and plain in style. If you are writing an argument paper that is less scientific, however, then you perhaps do want to have a more emotional style. You may want to use anecdotes and make a personal connection to your audience by using language that evokes strong thoughts in them.

But just imagine, now you have written the argument paper. You read it and notice that because you are very passionate about the topic you are arguing about, your paper is actually quite theatrical, full of emphasis and enthusiasm. If you know that this is acceptable to your audience, you will be fine. Make sure, though, that above all things, you do not sacrifice clear meaning on the altar of fine sounding dressed-up phrases. In most persuasive writing, logic and facts still need to be there. But you need to know who is going to be reading your paper and what they will be most persuaded by. A dry, factual style? A style full of passionately stated statistics? Stories?

Learning the rules and knowing the natures of those to whom you address can result in the most effective and difficult productions of texts: the ability to persuade different people of different or even opposite things with the same text.

Some writers can put people entirely into another state of being, as it were, and “transport them out of themselves” and put them into a heightened mind that is completely in the realm of our words; this is the “effect of genius” that Longinus writes of (163).

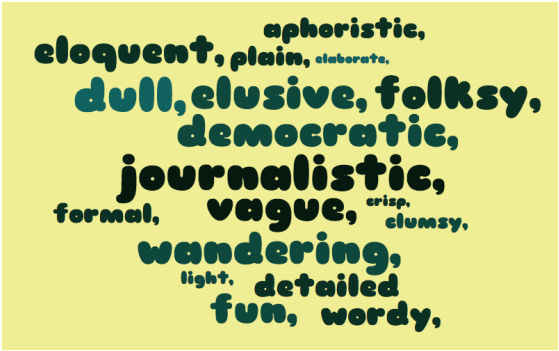

Describing style

A metaphor is a way of using one thing to explain another thing. Usually, in a metaphor, one is using something visible and concrete to explain something that is abstract and invisible. For example, to illustrate the un-see-able idea “power”, we might use this image:

For another example, in As You Like It, Shakespeare says that

All the world's a stage.

He takes something big and total, and abstract, “the world,” and puts it with something everyone can see and easily imagine a picture of in their mind, a “stage,” so that we can better understand what he means by “world,” because we all can see a stage.

So in talking about style, which is abstract, we tend to use metaphors. We say, for example, “Wordsworth sometimes writes in a very tender style.” The word “tender” is something that we associate with a person’s personality more than a certain kind of writing.

But this is how we talk about style, because it is hard to describe.

Graphic: Words to describe style

[Words: Aphoristic, eloquent, plain, elaborate, dull, elusive, folksy, democratic, journalistic, formal, vague, crisp, clumsy, wandering, light, detailed, fun, wordy]

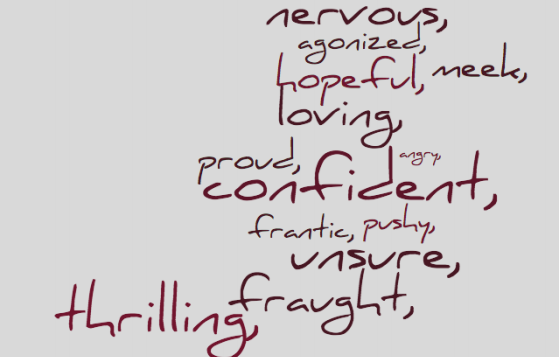

Tone

You can misunderstand the content of what someone says, and you can also misunderstand the tone, or spirit, of what they say. Sarcasm in conversation is an example of this. You can tell someone “Great job!” and mean it—he made a delicious cake!—or you can tell someone “Great job!” and not mean it—he forgot to add sugar. That is tone.

Tone is how content gets communicated to the audience. One thing useful to remember about tone is that even if your content is off, if your tone is agreed to and liked by your audience, you can still make inroads with that audience. In other words, it is at the level of tone that some of the most fruitful communication actually occurs.

This is because tone goes to motivation, or intent.

With communication, as in the law courts, intent dictates everything. In a court of law, you go to jail not based on whether you hit someone or not, but based on what your intent was when you did the hitting—was it accidental? Was it on purpose? What was your intent? What was the “spirit” or “tone” in which you did that act? The same is true of writing.

People can read your intent from what you write—they can feel your spirit, they can see your emotional landscape, they can perceive your motivations. They discern your aim. As Vygotsky put it, “To understand another’s speech, it is not sufficient to understand his words—we must understand his thought. But even that is not enough— we must also know its motivation” (125).

Thus, tone is also related to the character of the writer or speaker. And, remember what Aristotle says, that “moral character, so to say, constitutes the most effective means of proof” (17). This is what we called ethos earlier. In other words, having good moral character, or reputation and credentials, is often the most effective way to persuade an audience.

Graphic: Words to describe tone

[Words: nervous, agonized, hopeful, meek, loving, angry, proud, confident, frantic, pushy, unsure, fraught, thrilling]

And so, style and tone are closely related. To return now to style.