17.4: Annotated Student Sample- "Hints of the Homoerotic" by Leo Davis

- Page ID

- 141536

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Determine the context of an image.

- Analyze the rhetorical techniques common to images.

- Analyze a variety of texts according to organizational patterns and rhetorical techniques.

Introduction

Below you will find a student analysis of a painting by Charles Demuth. As you read it, pay careful attention to the way in which the student author, Leo Davis, describes technical details of the painting, such as color, line, and technique. Also notice the way he analyzes those details, moving beyond mere description into the realms of context, analysis, and reflection.

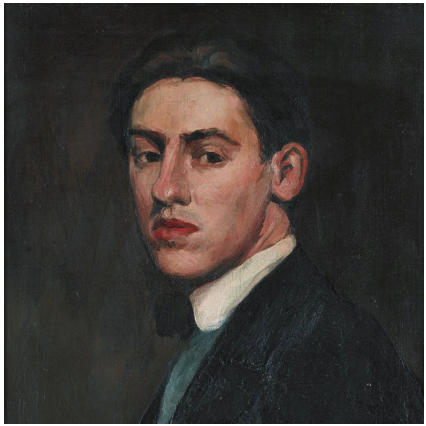

Meet American Modernist and Precisionist Charles Demuth (1883-1935)

Figure \(17.14\) Self-Portrait, 1907 (credit: “Self portrait of Charles Demuth” by Charles Demuth/Wikimedia Commons, CC0)

Charles Demuth was an American painter of the modernist and precisionist movements. Trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, he traveled to Europe and worked as an illustrator before striking out on his own, first as a watercolorist and then as an oil painter. His watercolors follow languid lines of vegetation, reproducing plants and flowers in stronger geometric patterns than those of his friend and fellow artist Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986). His work in the precisionist movement, like that of other similar artists, often focuses on industrial subjects enhanced by exaggerated geometric techniques. Few human characters appear in Demuth’s paintings, which tend to erase any suggestion of his own personality or brushstroke on the artwork.

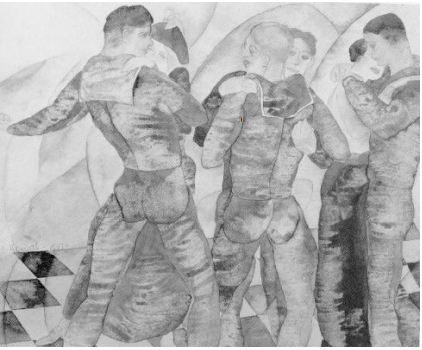

Demuth was a keen wit with a vibrant social presence in New York, Paris, and London. He cultivated his friendships as avidly as he did his art, and his company was much prized. His homosexuality was likely well known among his circle of friends, although his works depicting gay subculture in major metropolitan areas were only privately circulated. These works, including Dancing Sailors (https://openstax.org/r/Dancing-Sailors) seen in black and white in Figure \(17.15\), are today shedding light on the ways in which LGBTQ people engaged with one another and society more than 100 years ago.

Figure \(17.15\) Dancing Sailors, c. 1918, by Charles Demuth (credit: “Dancing sailors” by Charles Demuth/ Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Living By Their Own Words

Analysis of Dancing Sailors by Charles Demuth

Four male sailors dance on a checked floor with arched lines in the background. Two of the men dance with women, while two of them dance with each other. This painting is done in watercolor and graphite and focuses on the sailor on the far left. The other figures face him, and his posture draws the viewer’s eye to his face. The man and woman on the far right seem completely involved with each other. The two couples in the middle are drawn sensually, with passion, but none of them focus on their own partners. Instead, the two sailors with their backs to the viewer stare at one another. The sailor on the left appears quite aggressive, with an arched back and bent knees suggesting a pelvic thrust. Although his dance partner is a woman, he holds her right hand at arm’s length, away from his body, and stares past her toward the sailor next to him. Strong pencil strokes emphasize his eyes and eyebrows, pointing the viewer to the object of his stare. The central sailor is dancing with a man in a mutual embrace, but his attention is fixed on the sailor at left, his head tilted slightly and his expression receptive. The painting is signed and dated: “C Demuth - 1918 -.”

Description. The initial paragraph focuses extensively on the visual elements of the painting, with a few analytical passages. Leo Davis uses descriptive, artistic terminology such as “arched,” “watercolor and graphite,” and “[s]trong pencil strokes” to help readers visualize the painting.

Line and Arrangement. Davis provides some details about the artistic techniques used, such as the strong pencil strokes and the way the image “emphasize[s] his eyes and eyebrows.”

Analysis. The author explains the effect of these elements and techniques to interpret the poses and intentions of the characters in the painting.

A Vibrant Subculture and a World in Crisis

Dancing Sailors was painted by Charles Demuth (1883–1935), a key figure in early-20th-century modernism. Best known as a watercolorist, Demuth also painted the gay subculture in jazz clubs and underground bars in New York City in works that he kept secret. As a gay man, he frequently visited Manhattan during the Harlem Renaissance and participated in this culture, savoring the artistic and erotic intensity of the Jazz Age visited Manhattan during the Harlem Renaissae and participated in this culture, savoring the artistic and erotic intensity of the Jazz Age.

Although the art movement in the early 20th century was vibrant, its context was depressing. The United States entered World War I (1914–1918) in April 1917. A month later, the Selective Service Act was passed, and thousands of American men were drafted into military service. In March 1918, the United States was hit with the influenza pandemic. Twenty million people died in the war, and another 50 million died from the flu.

Meanwhile, in 1916, the U.S. military began using so-called blue discharges to force gay people out of the armed forces. By 1919, sailors were arrested and court-martialed for homosexual activity. It seems seriously unfair that someone who fought in the war could come back home and be convicted as a criminal just for his sexual orientation.

In this context, with death seemingly everywhere and gay men hated, Demuth created striking watercolors that say a lot about his times. Because he did not share these paintings publicly, he was probably afraid of revealing his own homosexuality. But that did not stop him from making art that reflected his own desires. Dancing Sailors, now in possession of the Cleveland Museum of Art in Ohio, was not intended for public exhibition.

Context. In these four well-organized paragraphs, Davis outlines the painting’s context: key details about the artist’s personal life, the military and domestic situations in America, and Demuth’s place in this world. Davis focuses on the aspects most relevant to the artwork, keeping the context short and pointed.

Tension within a Painting

The perspective, or point of view, of the painting is high, as shown by the angle of the black-and-white checkerboard floor and where it hits the wall. The figures are shown in a practical close-up, so that their feet and the tops of their heads are not included in the frame. This perspective is very intimate, but with the audience intruding on the scene. All of the couples hold each other closely and tightly, and the audience is almost uncomfortably close.

Point of View. Davis returns to technical description, indicating the artist’s perspective and how it affects the viewer.

Demuth uses watercolor to outline the dancers’ bodies, making the clothing almost transparent. The silhouette of the pants emphasizes the bulge of thigh and calf muscles, and the arches in the background suggest erections. For both men, the buttocks are outlined and emphasized. The male dancers are clearly wearing uniforms, but Demuth chooses not to include insignias, medals, or other identifying marks. Perhaps he was simply not interested in military rank and regulation. Or maybe he wanted to direct the viewer’s attention elsewhere. The two women in the painting are incidental, their bodies largely obscured by the men. Although the figures are outlined in graphite, the textured watercolor unites the dancers with the background, making them seem very much like they belong in this scene of intimacy.

Artistic Medium and Line. Davis discusses the medium—watercolor—and how Demuth’s use of it creates the impression of tight clothing. Importantly, the author does not assume intent on Demuth’s part, although he speculates. Instead, he limits his analysis to the details and artistic techniques of the painting.

Technical Description. Again, the author keeps this paragraph focused on an element of artistic design: the watercolor. He backs his assertion with evidence from the painting. Instead of simply saying that the men are wearing tight clothing, he describes the artist's use of watercolor to create the impression of tight clothing.

The painting appears to tell a story, but only in part. The viewer is invited to fill in the blanks. The sailors in the foreground are blatantly flirting with one another. And the central sailor’s direct stare at the viewer may be considered an invitation. His wide-eyed expression, slight smile, and hands curled to embrace his dance partner’s torso indicate pleasure. The viewer knows something this sailor does not: his part of this story is unlikely to have a happy ending. The female dance partners, while largely obscured, are still individuals with strong personalities. The woman on the left has a vacant stare from half-closed eyes, and her indifferent posture suggests that she may be bored, but the curve of her hip is still sexual. Is she offended by her partner’s distraction?

Arrangement. Davis invites viewers to “read” the painting, to see the story being told by the arrangement, which also invites them to notice the two women.

Rhetorical Question. This technique allows the student author to pose provocative questions that have no clear answers. In combination with the accompanying analysis, the rhetorical question helps establish the tone and theme of the painting that Leo Davis wishes to explore.

Lasting Significance

Demuth was a gay man during a difficult time in American history. This painting, one of many he kept private, is sympathetic and nonjudgmental. These private paintings may have been his attempt to find and show his acceptance of his own identity. During World War I, many military men came to port cities such as New York. Also during that time, Demuth enjoyed the Manhattan nightlife, and he painted a number of scenes of this changing environment. His personal involvement is interesting in and of itself. But even more so, these private paintings document the emergence of a sexual subculture and mark an important moment in American gay history.

Context and Analysis. The author uses context and analysis to reach a conclusion about Demuth’s intention in creating the painting and its significance in the history of American homoerotic art.

Although Demuth died at the relatively early age of 52, his work remains influential in American art. The geometric background of Dancing Sailors shows his increased interest in architectural watercolors. Later in his career, these paintings were hailed as key to the development of the precisionist movement. His unique expressions of modernism are a precursor to the abstract expressionism that developed in the 1940s and later influenced pop art innovators such as Andy Warhol (1928–1987). Aside from its historical significance, the vibrant sensuousness of Dancing Sailors continues to have relevance and appeal for art lovers today.

Context. Leo Davis concludes by extending his argument for Demuth’s influence, tracing the effect of his work through later artists and movements and stating the reason Dancing Sailors continues to have value as a work of art

Discussion Questions

- In which of the three types of writing about art—reflecting, analyzing, persuading— is the student author engaging? How do you know?

- Identify some of the descriptive language specific to visuals that Leo Davis uses when talking about the painting. How does this language enhance the paper and contribute to the discussion?

- From the essay, can you determine Davis’s opinion regarding homosexuality? Why might this tone be or not be a significant part of the rhetorical situation?

- What details does the student author include about the painter? Is any information about the painter excluded that you think would be relevant?