16.4: Annotated Student Sample- "Artists at Work" by Gwyn Garrison

- Page ID

- 140730

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Demonstrate understanding of how conventions are shaped by purpose, language, culture, and expectation.

- Demonstrate critical thinking and communicating in varying rhetorical and cultural contexts.

- Make connections between ideas and patterns of organization.

- Evaluate literary elements and strategies used in textual analysis.

Introduction

Student Gwyn Garrison wrote this textual analysis for a first-year composition class. In the essay, Garrison extends her analysis beyond the texts to discuss outside events and real individuals, making connections among them.

Living By Their Own Words

The Power of Language

Language is the medium thorugh which the communication of ideas takes place. One of language's many attributes is its ability both to reflect and to shape social attitudes. Language has the power to perpetuate oppression when dominant social groups choose the ways in which rebellious behavior is described. Thus, people in power historically have used language as propoganda to perpetuate the ideas that they want to reiterate. For example, if woman in modern society is described as ladylike, the message is that she conforms to traditional gender expectations of politeness, modesty, and deference. However, if a woman is called a whore, the message is that the woman does not conform to these traditional gender standards. In recent years, oppressed social groups have learned that they can reclaim the language of the oppressor by redefining such words and their connotations.

Gwyn Garrison uses reaction—reflection or thinking—to introduce the “big idea” of the thesis: language has the power to shape cultural and social attitude.

American authors such as Kate Chopin and Shirley Jackson, sociopolitical activists such as Hillary Clinton and Chrissy Teigen, and California rape survivor Chanel Miller— artists/writers in their own ways—take on this essential work of reclaiming language on behalf of all women. This confiscation of the tools of the oppressor is an essential step toward building a society in which women may be free to be who they are. Negative stereotypical labeling no longer has the effect of disempowering women because language can be reclaimed from the oppressor as a form of empowerment.

Garrison’s thesis statement highlights her analytical approach. She makes a connection between women’s rights and a series of texts by significant women.

Writers can use the short story form to shift perception away from the lens of the status quo and focus perception in a new way. In Kate Chopin’s 1898 short story “The Storm” (text follows this discussion), protagonist Calixta engages in a passionate extramarital affair with an old friend, Alcée. Readers may argue that Calixta’s actions should be labeled as immoral by both societal and religious standards because she breaks the social and religious contract defined by her marriage vows. Yet every other action of Calixta’s complies with traditional gender roles: she is a wife, mother, and caretaker. In some ways, committing this one social transgression seems completely out of character when she meets traditional gender expectations in all other areas of her life.

Garrison provides publication information as well as a brief plot summary and context for the story. You can read “The Storm” in its entirety at the end of this feature.

When Calixta acts outside of societal norms, however, she discovers the freedom of self-expression and passion.

This transitional topic sentence supports the overall thesis while also identifying what the paragraph will be about.

All parts of her womanhood that have no place in the society in which she lives have been repressed until this one moment. In this scene, Chopin takes possession of the term whore and redefines Calixta’s behavior as a transformative awakening.

This explanation makes a reference to the language of the text and explains the significance of the scene as it relates to the entire story and to Garrison’s thesis.

Chopin’s diction evokes a spiritual transcendence that allows Calixta to live momentarily outside social norms present only in the physical plane of existence: “when he possessed her, they seemed to swoon together at the very borderland of life’s mystery."

Here, Garrison correctly cites textual evidence—an example of the protagonist’s diction— to support her reasoning.

The affair becomes a vehicle that allows Calixta to get to a place of true self-expression. The storm, an aspect of nature or the natural world, acts as the catalyst in Calixta’s natural self-realization of womanhood. As the storm breaks externally, it also breaks internally for Calixta. Chopin’s depiction of Calixta’s sexual liberation and fulfillment outside of her marriage is an early step in the fight to bridge the gap between women’s bodies and their sociopolitical lives. By presenting female secxuality in a way that is enlightening rather than degrading. Chopin helps destigmatize labeles such as whore, which have been used to shame women for acting outside of traditional gender expectations.

Garrison further elaborates on the significance of the textual evidence and connects it to the topic sentence and thesis. In this case,it is the storm—an element of both plot and setting as well as a symbo

In Shirley Jackson’s novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Merricat and her sister Constance are rumored to be witches who, according to village gossip, eat children. The label of witch has long been a device to oppress women who do not conform to traditional gender roles. In Salem, Massachusetts, during the 17thcentury witch trials, women who could read or write, who refused marriage, or who practiced alternative religions often were labeled as witches and burned to death.

Introducing a second text for comparison, Garrison revisits the idea of language reclamation introduced earlier.

In Jackson’s novel, Merricat embraces the notion of being labeled a witch. In fact, she facilitates the rumors by burying talismans, identifying magical words, and talking to her cat, Jonas. In contrast to the witch trials, Merricat burns her own house to rid it of her male cousin. And she survives the fire, purging herself and her sister of the family’s patriarchal tendencies. By claiming the role of witch, Merricat insulates herself and her sister from their patriarchal family and society. In the end, Merricat creates a space where she and Constance can live together in a woman-centered territory outside the reach of the villagers.

Focusing on language and its implications, Garrison discusses the use of witch, a label the character is happy to embrace as a means of asserting her womanhood.

With this story, Jackson does the important work of reclaiming the word witch, stripping it of its oppressive power and redefining it for womankind.

In the section that follows, Garrison moves outside literary texts and extends her analysis to language use in contemporary political situations, thus connecting literature with reality. Notice that Garrison has used the literary present tense in discussing both Chopin’s and Jackson’s fiction. She switches and uses mostly past tense now in discussing nonliterary events.

Similarly, in a more recent political climate, former U.S. president Donald Trump employed stereotypical derogatory language against women whom he considered dissenters. He used phrases like “such a nasty woman” (Ali) to describe former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and “filthy mouthed wife” (@realDonaldTrump) to describe model Chrissy Teigen to try to shame women with social influence into submission. It is noteworthy, too, that he describes Teigen by her role in relation to a man rather than by her name, which would indicate her individuality. Both Clinton and Teigen, along with millions of women around the world, have worked to empower women by redefining such language. Almost immediately following the accusation of “such a nasty woman,” women and girls around the country donned t-shirts and ball caps with the phrase, showing their pride in being “nasty” (Ali). In this context, the term came to describe women who speak truth to power. Although Teigen acknowledges that she had previously been blocked by Trump for trolling him, she shot back defiantly at him with a tweet that read in part: “lol what p— a— b—” (@chrissyteigen). Shortly thereafter, the phrase was trending as a Twitter hashtag (Butler). In this instance, people, particularly women, appreciated Teigen’s ability to respond to female shaming with language that Trump himself was recorded using and that is also traditionally used to shame and degrade women. This time, however, it was directed toward a powerful man. This reclamation of power through language is one step women have taken to revise the social gender narrative for a modern context.

Again, Garrison introduces texts for comparison, bringing her argument regarding the reclamation of language into the modern day.

After four years of being known as “the girl raped by Stanford swimmer Brock Turner,” sexual assault survivor Chanel Miller has reclaimed the narrative of her story with the publication of her memoir Know My Name. After a Stanford University fraternity party in January 2015, Turner assaulted (with intent to rape) an intoxicated and unconscious Miller behind a dumpster at approximately 1:00 a.m. Some passing students interrupted the act, and Turner was taken by the police after the students restrained him. He was later brought to trial and found guilty. The sympathetic male judge sentenced Turner to only six months in county jail, from which he was released after three months for good behavior. When speaking on television to 60 Minutes on September 22, 2019, Miller expressed outrage that media coverage during the trial had focused not on what Miller had already lost but on what Turner had to lose if found guilty—his education, his swimming career, his Olympic prospects (Miller). Because Miller remained anonymous during the trial, the media and Turner’s lawyers controlled how she was perceived to the world—as a girl who got drunk and put herself into a compromising situation.

Garrison emphasizes the role oflanguage in Miller's telling her story and ceasing to feel ashamed.

This male-centric characterization of events left Miller feeling ashamed and disempowered. By writing her book and reclaiming her story, Miller took a vital step in healing and trauma management, emphasizing that she now controls the language of her narrative. She is not a girl who deserves what she got, as some would argue. Miller readily acknowledges she deserved a hangover for her actions, but never a rape.

Notice the switching of tenses to indicate events in the past and present. Notice, too, that Garrison returns to the literary present tense in the paragraph that follows.

Miller’s story is all too common in the college partying scene, and the regularity of such attacks contributes to the perpetuation of an environment in which women are made to feel responsible for being attacked and men are free to act as they choose. The awareness of Miller’s story and, more importantly, her published story, reframe the narrative around rape culture so that the victims are not further victimized, as women work to educate men so that these attacks stop.

Garrison introduces a final contemporary text for comparison. By citing multiple texts across time, Garrison strengthens her argument.

Artists and writers such as Chopin, Jackson, Clinton, Teigen, and Miller engage in the gritty work of social reform that cannot be achieved through any other medium because culture cannot change unless the language in which people talk about the culture changes. This socially reformed reality is conceived only from the creativity of intelligent minds that are able both to envision and then to describe the world as it is yet to exist. In this way, artists who work with the medium of language become the prophets.

This conclusion looks to the future, which is a productive rhetorical or persuasive technique to give the audience an idea about what they can take away from this project.

Works Cited

Ali, Lorraine. “‘Such a Nasty Woman’: Trump’s Debate Dig Becomes a Feminist Rallying Cry.” Los Angeles Times, 20 Oct. 2016, www.latimes.com/entertainment/tv/la-et-nasty-woman-trump-clinton-debate-jane-jackson-20161020-snap-story.html.

Butler, Bethonie. “Trump Called Chrissy Teigen a ‘Filthy Mouthed Wife.’ Her Response Reflects Years of Social Media Savvy.” Washington Post, 10 Sept. 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/arts-entertainment/2019/09/10/trump-called-chrissy-teigen-filthy-mouthed-wife-her-response-reflects-years-social-media-savvy/.

Chopin, Kate. “The Storm.” 1898. American Literature.com, 2018, americanliterature.com/author/kate-chopin/ short-story/the-storm.

@chrissyteigen. “lol what a pussy ass bitch. tagged everyone but me. an honor, mister president.” Twitter, 8 Sept. 2019, 11:17 p.m. https://twitter.com/chrissyteigen/st...590914?lang=en.

Jackson, Shirley. We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Penguin Classics, 1962.

Miller, Chanel. “Interview with Bill Whitaker.” 60 Minutes. 22 Sept. 2019.

@realDonaldTrump. “...musician @johnlegend, and his filthy mouthed wife, are talking now about how great it is - but I didn’t see them around when we needed help getting it passed. “Anchor”@LesterHoltNBC doesn’t even bring up the subject of President Trump or the Republicans when talking about...” Twitter, 8 Sept. 2019, 10:11 p.m.

Garrison follows MLA guidelines to cite her sources.

Discussion Questions

- How might Gwyn Garrison have used action to introduce her thesis? Dialogue? Is reaction the best choice? Why or why not?

- What reasoning does Garrison offer to support her thesis?

- What textual evidence does Garrison offer to support her thesis?

- How does Garrison connect literary elements—particularly language and character—with real-world events? Explain why you think these connections are valid or not.

- Are you convinced or unconvinced of the validity of the thesis? Why or why not?

For Reference: "The Storm" by Kate Chopin (1850-1904)

Figure \(16.5\) American author Kate Chopin, 1894 (credit: “KATE O’FLAHERTY BEFORE HER MARRIAGE TO OSCAR CHOPIN” by J.A. Scholten/The State Historical Society of Missouri, Photograph Collection, Public Domain)

The leaves were so still that even Bibi thought it was going to rain. Bobinôt, who was accustomed to converse on terms of perfect equality with his little son, called the child’s attention to certain sombre clouds that were rolling with sinister intention from the west, accompanied by a sullen, threatening roar. They were at Friedheimer’s store and decided to remain there till the storm had passed. They sat within the door on two empty kegs. Bibi was four years old and looked very wise.

“Mama’ll be ’fraid, yes,” he suggested with blinking eyes.

“She’ll shut the house. Maybe she got Sylvie helpin’ her this evenin’,” Bobinôt responded reassuringly.

“No; she ent got Sylvie. Sylvie was helpin’ her yistiday,” piped Bibi.

Bobinôt arose and going across to the counter purchased a can of shrimps, of which Calixta was very fond. Then he returned to his perch on the keg and sat stolidly holding the can of shrimps while the storm burst. It shook the wooden store and seemed to be ripping great furrows in the distant field. Bibi laid his little hand on his father’s knee and was not afraid.

II

Calixta, at home, felt no uneasiness for their safety. She sat at a side window sewing furiously on a sewing machine. She was greatly occupied and did not notice the approaching storm. But she felt very warm and often stopped to mop her face on which the perspiration gathered in beads. She unfastened her white sacque at the throat. It began to grow dark, and suddenly realizing the situation she got up hurriedly and went about closing windows and doors.

Out on the small front gallery she had hung Bobinôt’s Sunday clothes to dry and she hastened out to gather them before the rain fell. As she stepped outside, Alcée Laballière rode in at the gate. She had not seen him very often since her marriage, and never alone. She stood there with Bobinôt’s coat in her hands, and the big rain drops began to fall. Alcée rode his horse under the shelter of a side projection where the chickens had huddled and there were plows and a harrow piled up in the corner.

“May I come and wait on your gallery till the storm is over, Calixta?” he asked.

“Come ’long in, M’sieur Alcée.”

His voice and her own startled her as if from a trance, and she seized Bobinôt’s vest. Alcée, mounting to the porch, grabbed the trousers and snatched Bibi’s braided jacket that was about to be carried away by a sudden gust of wind. He expressed an intention to remain outside, but it was soon apparent that he might as well have been out in the open: the water beat in upon the boards in driving sheets, and he went inside, closing the door after him. It was even necessary to put something beneath the door to keep the water out.

“My! what a rain! It’s good two years since it rain’ like that,” exclaimed Calixta as she rolled up a piece of bagging and Alcée helped her to thrust it beneath the crack.

She was a little fuller of figure than five years before when she married; but she had lost nothing of her vivacity. Her blue eyes still retained their melting quality; and her yellow hair, dishevelled by the wind and rain, kinked more stubbornly than ever about her ears and temples.

The rain beat upon the low, shingled roof with a force and clatter that threatened to break an entrance and deluge them there. They were in the dining room—the sitting room—the general utility room. Adjoining was her bedroom, with Bibi’s couch alongside her own. The door stood open, and the room with its white, monumental bed, its closed shutters, looked dim and mysterious.

Alcée flung himself into a rocker and Calixta nervously began to gather up from the floor the lengths of a cotton sheet which she had been sewing.

“If this keeps up, Dieu sait if the levees goin’ to stan it!” she exclaimed.

“What have you got to do with the levees?”

“I got enough to do! An’ there’s Bobinôt with Bibi out in that storm—if he only didn’ left Friedheimer’s!”

“Let us hope, Calixta, that Bobinôt’s got sense enough to come in out of a cyclone.”

She went and stood at the window with a greatly disturbed look on her face. She wiped the frame that was clouded with moisture. It was stiflingly hot. Alcée got up and joined her at the window, looking over her shoulder. The rain was coming down in sheets obscuring the view of far-off cabins and enveloping the distant wood in a gray mist. The playing of the lightning was incessant. A bolt struck a tall chinaberry tree at the edge of the field. It filled all visible space with a blinding glare and the crash seemed to invade the very boards they stood upon.

Calixta put her hands to her eyes, and with a cry, staggered backward. Alcée’s arm encircled her, and for an instant he drew her close and spasmodically to him.

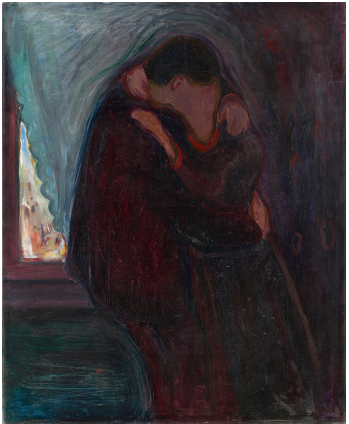

Figure \(16.6\) The Kiss, 1887, by Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863–1944) (credit: “Edvard Munch - The Kiss” by Google Art Project/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

“Bonté!” she cried, releasing herself from his encircling arm and retreating from the window, “the house’ll go next! If I only knew w’ere Bibi was!” She would not compose herself; she would not be seated. Alcée clasped her shoulders and looked into her face. The contact of her warm, palpitating body when he had unthinkingly drawn her into his arms, had aroused all the old-time infatuation and desire for her flesh.

“Calixta,” he said, “don’t be frightened. Nothing can happen. The house is too low to be struck, with so many tall trees standing about. There! Aren’t you going to be quiet? say, aren’t you?” He pushed her hair back from her face that was warm and steaming. Her lips were as red and moist as pomegranate seeds. Her white neck and a glimpse of her full, firm bosom disturbed him powerfully. As she glanced up at him the fear in her liquid blue eyes had given place to a drowsy gleam that unconsciously betrayed a sensuous desire. He looked down into her eyes and there was nothing for him to do but to gather her lips in a kiss. It reminded him of Assumption.

“Do you remember—in Assumption, Calixta?” he asked in a low voice broken by passion. Oh! she remembered; for in Assumption he had kissed her and kissed her; until his senses would well nigh fail, and to save her he would resort to a desperate flight. If she was not an immaculate dove in those days, she was still inviolate; a passionate creature whose very defenselessness had made her defense, against which his honor forbade him to prevail. Now—well, now—her lips seemed in a manner free to be tasted, as well as her round, white throat and her whiter breasts.

They did not heed the crashing torrents, and the roar of the elements made her laugh as she lay in his arms. She was a revelation in that dim, mysterious chamber; as white as the couch she lay upon. Her firm, elastic flesh that was knowing for the first time its birthright, was like a creamy lily that the sun invites to contribute its breath and perfume to the undying life of the world. The generous abundance of her passion, without guile or trickery, was like a white flame which penetrated and found response in depths of his own sensuous nature that had never yet been reached.

When he touched her breasts they gave themselves up in quivering ecstasy, inviting his lips. Her mouth was a fountain of delight. And when he possessed her, they seemed to swoon together at the very borderland of life’s mystery.

He stayed cushioned upon her, breathless, dazed, enervated, with his heart beating like a hammer upon her. With one hand she clasped his head, her lips lightly touching his forehead. The other hand stroked with a soothing rhythm his muscular shoulders.

The growl of the thunder was distant and passing away. The rain beat softly upon the shingles, inviting them to drowsiness and sleep. But they dared not yield.

The rain was over; and the sun was turning the glistening green world into a palace of gems. Calixta, on the gallery, watched Alcée ride away. He turned and smiled at her with a beaming face; and she lifted her pretty chin in the air and laughed aloud.

III

Bobinôt and Bibi, trudging home, stopped without at the cistern to make themselves presentable.

“My! Bibi, w’at will yo’ mama say! You ought to be ashame’. You oughta’ put on those good pants. Look at ’em! An’ that mud on yo’ collar! How you got that mud on yo’ collar, Bibi? I never saw such a boy!” Bibi was the picture of pathetic resignation. Bobinôt was the embodiment of serious solicitude as he strove to remove from his own person and his son’s the signs of their tramp over heavy roads and through wet fields. He scraped the mud off Bibi’s bare legs and feet with a stick and carefully removed all traces from his heavy brogans. Then, prepared for the worst—the meeting with an over-scrupulous housewife, they entered cautiously at the backdoor.

Calixta was preparing supper. She had set the table and was dripping coffee at the hearth. She sprang up as they came in.

“Oh, Bobinôt! You back! My! but I was uneasy. W’ere you been during the rain? An’ Bibi? he ain’t wet? he ain’t hurt?” She had clasped Bibi and was kissing him effusively. Bobinôt’s explanations and apologies which he had been composing all along the way, died on his lips as Calixta felt him to see if he were dry, and seemed to express nothing but satisfaction at their safe return.

“I brought you some shrimps, Calixta,” offered Bobinôt, hauling the can from his ample side pocket and laying it on the table.

“Shrimps! Oh, Bobinôt! you too good fo’ anything!” and she gave him a smacking kiss on the cheek that resounded, “J’vous réponds, we’ll have a feas’ to-night! umph-umph!”

Bobinôt and Bibi began to relax and enjoy themselves, and when the three seated themselves at table they laughed much and so loud that anyone might have heard them as far away as Laballière’s.

IV

Alcée Laballière wrote to his wife, Clarisse, that night. It was a loving letter, full of tender solicitude. He told her not to hurry back, but if she and the babies liked it at Biloxi, to stay a month longer. He was getting on nicely; and though he missed them, he was willing to bear the separation a while longer—realizing that their health and pleasure were the first things to be considered.

V

As for Clarisse, she was charmed upon receiving her husband’s letter. She and the babies were doing well. The society was agreeable; many of her old friends and acquaintances were at the bay. And the first free breath since her marriage seemed to restore the pleasant liberty of her maiden days. Devoted as she was to her husband, their intimate conjugal life was something which she was more than willing to forego for a while. So the storm passed and everyone was happy.