4.5.5: Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

- Page ID

- 188192

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

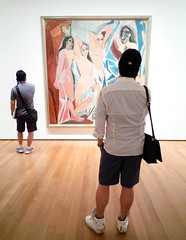

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, oil on canvas, 243.9 x 233.7 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Cézanne’s ghost, Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre, and Picasso’s ego

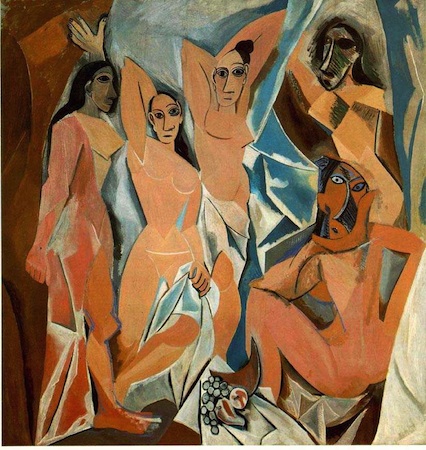

One of the most important canvases of the twentieth century, Picasso’s great breakthrough painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was constructed in response to several significant sources.

First amongst these was his confrontation with Cézanne’s great achievement at the posthumous retrospective mounted in Paris a year after the artist’s death in 1907.

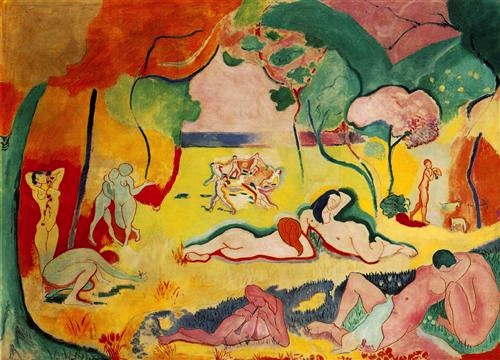

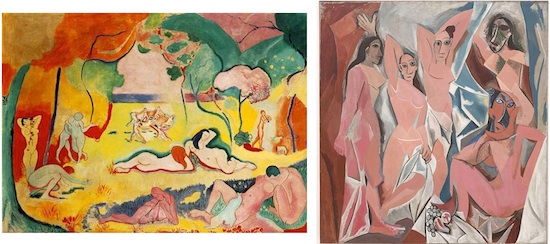

The retrospective exhibition forced the young Picasso, Matisse, and many other artists to contend with the implications of Cézanne’s art. Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre of 1906 was one of the first of many attempts to do so, and the newly completed work was quickly purchased by Leo & Gertrude Stein and hung in their living room so that all of their circle of avant-garde writers and artists could see and praise it. And praise it they did. Here was the promise of Cézanne fulfilled—and one which incorporated lessons learned from Seurat and van Gogh, no less! This was just too much for the young Spaniard.

Pablo becomes Picasso

By all accounts, Picasso’s intensely competitive nature literally forced him to out do his great rival. Les Demoiselles D’Avignon is the result of this effort. Let’s compare canvases. Matisse’s landscape is a broad open field with a deep recessionary vista. The figures are uncrowded. They describe flowing arabesques that in turn relate to the forms of nature that surround them. Here is languid sensuality set in the mythic past of Greece’s golden age.

In very sharp contrast, Picasso, intent of making a name for himself (rather like the young Manet and David), has radically compressed the space of his canvas and replaced sensual eroticism with a kind of aggressively crude pornography. (Note, for example, the squatting figure at the lower right.) His space is interior, closed, and almost claustrophobic. Like Matisse’s later Blue Nude (itself a response to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon), the women fill the entire space and seem trapped within it. No longer set in a classical past, Picasso’s image is clearly of our time. Here are five prostitutes from an actual brothel, located on a street named Avignon in the red-light district in Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia in northern Spain—a street, by the way, which Picasso had frequented.

Picasso has also dispensed with Matisse’s clear, bright pigments. Instead, the artist chooses deeper tones befitting urban interior light. Gone too, is the sensuality that Matisse created. Picasso has replaced the graceful curves of Bonheur de Vivre with sharp, jagged, almost shattered forms. The bodies of Picasso’s women look dangerous as if they were formed of shards of broken glass. Matisse’s pleasure becomes Picasso’s apprehension. But while Picasso clearly aims to “out do” Matisse, to take over as the most radical artist in Paris, he also acknowledges his debts. Compare the woman standing in the center of Picasso’s composition to the woman who stands with elbows raised at the extreme left of Matisse’s canvas: like a scholar citing a borrowed quotation, Picasso footnotes.

The creative vacuum-cleaner

Picasso draws on many other sources to construct Les Demoiselles D’Avignon. In fact, a number of artists stopped inviting him to their studio because he would so freely and successfully incorporate their ideas into his own work, often more successfully than the original artist. Indeed, Picasso has been likened to a “creative vacuum cleaner,” sucking up every new idea that he came across. While that analogy might be a little coarse, it is fair to say that he had an enormous creative appetite. One of several historical sources that Picasso pillaged is archaic art, demonstrated very clearly by the left-most figure of the painting, who stands stiffly on legs that look awkwardly locked at the knee. Her right arm juts down while her left arm seems dislocated (this arm is actually a vestige of a male figure that Picasso eventually removed). Her head is shown in perfect profile with large almond shaped eyes and a flat abstracted face. She almost looks Egyptian. In fact, Picasso has recently seen an exhibition of archaic (an ancient pre-classical style) Iberian (from Iberia–the land mass that makes up Spain and Portugal) sculpture at the Louvre. Instead of going back to the sensual myths of ancient Greece, Picasso is drawing on the real thing and doing so directly. By the way, Picasso purchased, from Apollinaire’s secretary, two archaic Iberian heads that she had stolen from the Louvre! Some have suggested that they were taken at Picasso’s request. Years later Picasso would anonymously return them.

Spontaneity, carefully choreographed

Because the canvas is roughly handled, it is often thought to be a spontaneous creation, conceived directly. This is not the case. It was preceded by nearly one hundred sketches. These studies depict different configurations. In some there are two men in addition to the women. One is a sailor. He sits in uniform in the center of the composition before a small table laden with fruit, a traditional symbol of sexuality. Another man originally entered from the left. He wore a brown suit and carried a textbook, he was meant to be a medical student.

The (male) artist’s gaze

Each of these male figures was meant to symbolize an aspect of Picasso. Or, more exactly, how Picasso viewed these women. The sailor is easy to figure out. The fictive sailor has been at sea for months, he is an obvious reference to pure sexual desire. The medical student is trickier. He is not there to look after the women’s health but he does see them with different eyes. While the sailor represents pure lust, the student sees the women from a more analytic perspective. He understands how their bodies are constructed, etc. Could it be that Picasso was expressing the ways that he saw these women? As objects of desire, yes, but also, with a knowledge of anatomy probably superior to many doctors. What is important is that Picasso decides to remove the men. Why? Well, to begin, we might imagine where the women focused their attention in the original composition. If men are present, the prostitutes attend to them. By removing these men, the image is no longer self-contained. The women now peer outward, beyond the confines of the picture plane that ordinarily protect the viewer’s anonymity. If the women peer at us, like in Manet’s Olympia of 1863, we, as viewers, have become the customers. But this is the twentieth century, not the nineteenth and Picasso is attempting a vulgar directness that would make even Manet cringe.

Picasso’s perception of space

So far, we have examined the middle figure which relates to Matisse’s canvas; the two masked figures on the right side who refer, by their aggression, to Picasso’s fear of disease; and, we have linked the left-most figure to archaic Iberian sculpture and Picasso’s attempt to elicit a sort of crude primitive directness. That leaves only one woman unaccounted for. This is the woman with her right elbow raised and her left hand on a sheet pulled across her left thigh. The table with fruit that had originally been placed at the groin of the sailor is no longer round, it has lengthened, sharpened, and has been lowered to the edge of the canvas. This table/phallus points to this last woman. Picasso’s meaning is clear, the still life of fruit on a table, this ancient symbol of sexuality, is the viewer’s erect penis and it points to the woman of our choice. Picasso was no feminist. In his vision, the viewer is male.

Although explicit, this imagery only points to the key issue. The woman that has been chosen is handled distinctly in terms of her relation to the surrounding space. Yes, more about space. Throughout the canvas, the women and the drapery (made of both curtains and sheets) are fractured and splintered. Here is Picasso’s response to Cezanne and Matisse. The women are neither before nor behind. As in Matisse’s Red Studio, which will be painted four years later, Picasso has begun to try to dissolve the figure/ground relationship. Now look at the woman that Picasso tells us we have chosen. Her legs are crossed and her hand rests behind her head, but although she seems to stand among the others, her position is really that of a figure that lies on her back. The problem is, we see her body perpendicular to our line of sight. Like Matisse and Cezanne before him, Picasso here renders two moments in time: as you may have figured out, we first look across at the row of women, and then we look down on to the prostitute of our/Picasso’s choice.

African masks, women colonized

The two figures at the right are the most aggressively abstracted with faces rendered as if they wear African masks. By 1907, when this painting was produced, Picasso had begun to collect such work. Even the striations that represent scarification is evident. Matisse and Derain had a longer standing interest in such art, but Picasso said that it was only after wandering into the Palais du Trocadero, Paris’s ethnographic museum, that he understood the value of such art. Remember, France was a major colonial power in Africa in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Much African art was ripped from its original geographic and artistic context and sold in Paris. Although Picasso would eventually become more sophisticated regarding the original uses and meaning of the non-Western art that he collected, in 1907 his interest was largely based on what he perceived as its alien and aggressive qualities.

William Rubin, once the senior curator of the department of painting and sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art, and a leading Picasso scholar, has written extensively about this painting. He has suggested that while the painting is clearly about desire (Picasso’s own), it is also an expression of his fear. We have already established that Picasso frequented brothels at this time so his desire isn’t in question, but Rubin makes the case that this is only half the story. Les Demoiselles D’Avignon is also about Picasso’s intense fear…his dread of these women or more to the point, the disease that he feared they would transmit to him. In the era before antibiotics, contracting syphilis was a well founded fear. Of course, the plight of the women seems not to enter Picasso’s story.