6.2.4: Christian Ethiopian art

- Page ID

- 161157

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Ethiopia is a country in Africa with ancient Christian roots. It possesses a vigorous artistic tradition and is home to hundreds of old churches and monasteries perched at the top of hard-to-access mountains, hidden by lush vegetation, or surrounded by the tranquil waters of one of its lakes.

What is Christian Ethiopian art?

The introduction of Christian elements in art and the construction of churches in Ethiopia must have started shortly after the introduction of Christianity and continues to this day, since about half of the population are practicing Christians. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church claims that Christianity reached the country in the 1st century C.E. (thanks to the conversion of the Ethiopian eunuch described in the Acts of the Apostles 8:26-38), while archaeological evidence suggests that Christianity spread after the conversion of the Ethiopian king Ezana during the first half of the 4th century C.E.

The term “Christian Ethiopian art” therefore refers to a body of material evidence produced over a long period of time. It is a broad definition of spaces and artworks with an Orthodox Christian character that encompasses churches and their decorations as well as illuminated manuscripts and a range of objects (crosses, chalices, patens, icons, etc.) which were used for the liturgy (public worship), for learning, or which simply expressed the religious beliefs of their owners. We can infer that from the thirteenth century onwards works of art were for the most part produced by members of the Ethiopian clergy.

Periodization

Artworks from Ethiopia can and should be contextualized within the country’s historical development. Scholars still disagree on how to divide and classify the development of Christian Ethiopian art into chronological phases. In this essay, the development of Christian Ethiopian art is broadly divided into the eight periods listed below, but it must be kept in mind that the dates for the earlier periods are still debated and we have very limited evidence prior to the early Solomonic period (1270-1527).

The Christian Aksumite Period (c. 4th-8th centuries C.E.)

This period takes its name from the city of Aksum which had been the capital of Ethiopia for several centuries before the conversion to Christianity of King Ezana (who ruled from c. 320–360) and served as capital for several centuries after. While we cannot rule out the possibility that Christianity had been present in the country prior to the conversion of this ruler, it is only starting from this period that expressions of distinctly Christian beliefs appear in the material record.

A small number of Ethiopian churches, such as Debre Damo (above) and Degum, can be tentatively ascribed to the Aksumite period. These two structures probably date to the 6th century or later. Still standing pre-6th century Aksumite churches have not been confidently identified. However, archaeologists believe that a small number of now-ruined structures dating to the 4th or 5th century functioned as churches—a conclusion based on features such as their orientation. A large stepped podium in the compound of the church of Mary of Zion in Aksum (considered by the Ethiopians as the dwelling place of the Ark of the Covenant), probably once gave access to a large church built during this period.

Aksumite churches adopted the basilica plan. These churches were constructed using well-established local building techniques and their style reflects local traditions. Although very little art survives from the Aksumite period, recent radiocarbon analyses of two illuminated Ethiopic manuscripts known as the Garima Gospels suggest that these were produced respectively between the 4th-6th and 5th-7th centuries. Aksumite coins (left) can also be looked at to gain insight into artistic conventions of the period.

The Post-Askumite period (c. 8th/9th-12th centuries C.E.)

A number of factors contributed to the gradual impoverishment and decline of the Aksumite kingdom. The Arab expansion into Northern Africa cut off the kingdom’s access to the Red-Sea waterway (and to the markets which could be reached through it and on which a large part of the kingdom’s prosperity had been based). There is also evidence to suggest that some of the kingdom’s natural resources, such as gold and ivory, had been depleted. Very little is known about this phase of Ethiopian history and scholars even disagree on the dates of its beginning and end.

The political center of Ethiopia seems to have gradually shifted to the southern and eastern parts of the Tigray region in the Post-Aksumite period. A few churches in these areas have been tentatively attributed to this period, but subsequent adaptations combined with the inability to obtain permissions to conduct archaeological surveys make dating difficult. It seems likely that churches continued to be built as well as hewn (cut) out of rock. A group of funerary hypogea (underground chambers) in the Hawzien plain (in northern Ethiopia) may have been transformed into churches during the post-Aksumite period. This could be the case for churches such as Abreha-we-Atsbeha (below) and Tcherqos Wukro (the paintings in these churches probably date from a later period). According to local oral traditions, a small number of iron crosses date to the Aksumite or Post-Aksumite periods, but the absence of reliable dating methods and the fact that such crosses were produced at least until the sixteenth century, makes it extremely difficult to verify these claims.

The Zagwe period (c. 1140-1270 C.E.)

By the first half of the twelfth century, the center of power of the Christian Kingdom had shifted even further south, to the Lasta region (a historic district in north-central Ethiopia). From their capital Adeffa, members of the Zagwe dynasty (from whom this period takes its name), ruled over a realm which stretched from much of modern Eritrea to northern and central Ethiopia. While limited evidence about their capital exists, the churches of Lalibela—a town which takes its name from the Zagwe ruler credited with its founding—stand as a testament to the artistic achievements of this period.

Lalibela includes twelve buildings destined for worship which, together with a network of linking corridors and chambers, are entirely carved or “hewn” out of living rock. The tradition of hewing churches out of rock, already attested in the previous periods, is here taken to a whole new level. The churches, several of which are free-standing, such as Bete Gyorgis (Church of St. George, image at top of page), have more elaborate and well-defined façades. They include architectural elements inspired by buildings from the Aksumite Period. Furthermore, some, such as Bete Maryam, feature exquisite internal decorations (above), which are also carved out of the rock, as well as wall paintings. The interiors of the churches blend Aksumite elements with more recent elements of Copto-Arabic derivation. In Bete Maryam, for example, the architectural elements—such as the hewn capitals and window frames—imitate Aksumite models (see below), whereas the paintings can be compared with those in the medieval Monastery of St. Antony at the Red Sea.

Several wooden altars survive from this period, some decorated with figures, together with numerous crosses, some of which are engraved. No illuminated manuscripts or icons from this period have been discovered thus far.

The Early Solomonic period (1270-1527)

By 1270, the last Zagwe ruler was overthrown by Yekunno Amlak, who claimed to descend from the kings of the Aksumite period and traced his lineage all the way back to the biblical union of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. His descendants—the Solomonics—ruled Ethiopia until the third quarter of the twentieth century. For much of this period, the Solomonics did not have a fixed capital, but moved across the country according to the seasons and their needs.

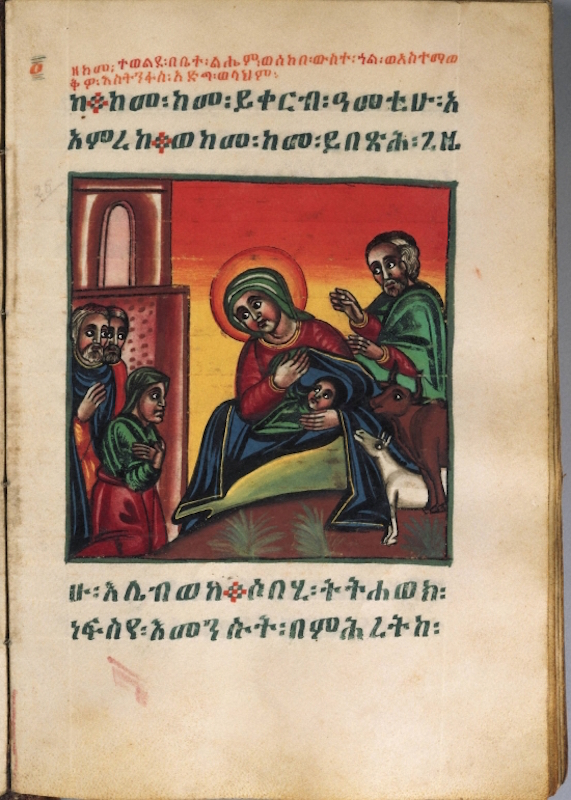

The Solomonics were as active as patrons of the arts as their predecessors, and endowed churches with hundreds of precious gifts. Works of art were also donated to ecclesiastic centers by nobles and clergymen, as well as by individuals known from dedicatory inscriptions on the work they commissioned. The rock-cut church of Gannata Maryam, a few kilometers south-east of Lalibela, features an almost complete set of murals depicting saints, angels, and motifs inspired by the New Testament. The church also features a portrait of Yekunno Amlak. Numerous illuminated manuscripts, particularly Gospel books, were created between the late thirteenth and early fifteenth centuries. A few dozen feature not just Canon Tables and portraits of the four Evangelists (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John), as in the earlier Garima Gospels, but also scenes from the Old and New Testaments.

By the turn of the fifteenth century other manuscripts, especially Psalters, are frequently illustrated and crosses are often embellished with depictions of saints and of the Virgin and Child (above). The earliest surviving Ethiopian icons also date from this century (above and below). Written sources suggest that the Ethiopian Emperor Zar’a Ya’eqob encouraged the use of panel paintings in church rituals. While other artistic mediums used during the fifteenth century are largely indebted to the art of the fourteenth century, the icons feature new iconographic motifs and the lines are more elegant and sinuous and the figures have less rigid poses.

The mid-Solomonic period (1527-1632)

After a period of relative stability in the fifteenth century, a sequence of events shook the Ethiopian kingdom to its foundations, bringing it to the brink of collapse. First, came an invasion from the neighboring Muslim Sultanate of Adal led by a general called Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi whose army pillaged and destroyed numerous churches and Christian works of art across the country between 1529 and 1543. Incursions by the Oromo people from the south throughout the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries further strained the country’s fragile structures. To make matters worse, the conversion to Catholicism of Emperor Susenyos in 1622 soon plunged the country into a civil war, for many of his subjects refused to adhere to the religious beliefs and liturgical practices that the Jesuit missionaries present in Ethiopia wanted to enforce. The conflict lasted until his abdication in favor of his son Fasilides in 1632.

This phase of Ethiopian art has been sometimes described as period of “transition” because artworks produced during the sixteenth century still include stylistic and iconographic elements that are typical of the fifteenth century, while foreshadowing developments which will take place in the second half of the seventeenth century. However, as such, this description of transition is applicable to most historical periods, and is therefore not particularly helpful. The art produced during the mid-Solomonic period reflects the difficult situation the country was in. The practice of decorating manuscripts with pictures and geometric motifs declined considerably, and few crosses and churches have been confidently attributed to the sixteenth century. Moreover, although numerous icons from this period have survived, these seldom achieve the linear elegance of painted panels from the fifteenth-century.

The Gondarine period (1632-1769)

The ascent to the throne of Fasilides in 1632 marks the beginning of a period of renewed stability for Ethiopia and the Solomonic dynasty. Fasilides ordered a new a capital, Gondar, about 50 kilometers north of Lake Tana (the largest lake in Ethiopia). He and his successors funded the construction of palaces and banquet halls within the royal compound that still exist today and they promoted the building of churches near by and in the Lake Tana region. The adoption of a circular plan for the construction of churches becomes standard (as opposed to the longitudinal format of the basilica).

Scholars usually divide the Gondarine period into two stylistic phases. The first Gondarine style (above), is characterized by the use of bright colors and the absence of shading. The clothing, often embellished with decorative elements, is usually painted in red, blue or yellow and the folds are indicating with simple parallel lines. The contour lines are well-defined and the modeling of the face is executed using a plain coral red resulting in an unnatural effect.

Works painted in the second Gondarine style (below), which was developed roughly during the reign of Iyasu II (1730-1755), have darker shades of color; the contour lines become lighter and a more delicate use of shading confers volume to the bodies and faces of the figures. A number of new themes, many of which were inspired from books printed in Europe, appear during the eighteenth century and it becomes increasingly common to find depictions of donors and patrons. Numerous crosses (like this processional cross from The British Museum), decorated with depictions of the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and saints were produced during the second part of the Gondarine period.

Zemene Mesafint period (1769-1855)

The period known as Zemene Mesafint, or the Era of Judges, begins with the deposition of Emperor Iyosas. This period, which lasted almost a century, saw a decline in the prestige, influence, and authority of the Solomonics, and witnessed the rise of a number of regional warlords who fought against each other for supremacy. This period has received less attention from historians, but seems to have been characterized by a decline in the production of art. Paintings from this period are strongly indebted to works executed during the second Gondarine style in terms of themes and forms, but the palette used by artists moves once again toward bright, plain colors.

The Late Solomonic period (1855-1974)

The final historical period begins with the ascent to the throne of Tewodros II, who claimed Solomonic descent and ends with the deposition of Haile Selassie, the event that marks the end of Solomonic rule in Ethiopia.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, church painting continues to show indebtedness to the second Gondarine style, but contemporary figures and events are depicted next to religious subjects with an increasing frequency. Moreover, while patrons had occasionally been depicted from the Zagwe period onwards in an idealized manner, by the turn of the twentieth century they are portrayed more realistically, as can be seen by the painting of Emperor Menelik II (above) in the church of Entoto Raguel. After the Second World War, traditionally trained Ethiopian painters, such as Qes Adamu Tesfaw, continued to work alongside artists influenced by modernism. The use of imported synthetic colors became increasingly common and by the 1960s icons and manuscripts were created, to a large extent, for the tourist market.

Additional resources

Biblical narrative of the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon (I Kings 10)