9.2.9: Bull-leaping fresco from the palace of Knossos

- Page ID

- 163370

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Taking the bull by the horns

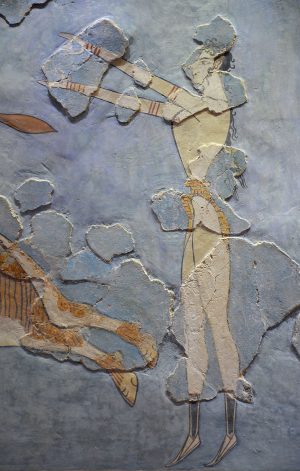

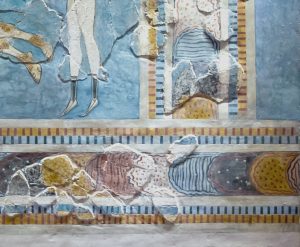

Bull sports—including leaping over them, fighting them, running from them, or riding them—have been practiced all around the globe for millennia. Perhaps the best-loved ancient illustration of this, called the bull-leaping or Toreador fresco, comes from the site of Knossos on the island of Crete. The wall painting, as it is now reconstructed, shows three people leaping over a bull: one person at its front, another over its back, and a third at its rear.

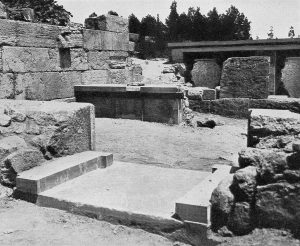

The image is a composite of at least seven panels, each .78 meters (about 2.5 feet) high. Fragments of this extensive wall painting were found very badly damaged in the fill above the walls in the Court of the Stone Spout, on the east side of the Central Court at Knossos. The fact that the paintings were found in fill indicates that this wall painting was destroyed as part of a renovation. The pottery which was found together with the fragments gives us its date, likely LM II (around 1400 B.C.E.).

Reconstructed but still incomplete

When Sir Arthur Evans, the first archaeologist to work at Knossos, found the fragments, he recognized them as illustrating an early example of bull sports, and he was eager to create a complete image that he could share with the world. He hired a well-known archaeological restorer, Émile Gilliéron, to create the image we know today from the largest bits of the seven panels. Unfortunately, it is impossible to reconstruct all of the original panels and to get a sense of the painting at all, we are left with Gilliéron’s reconstruction.

Visual gymnastics

What we see is a freeze-frame of a very fast moving scene. The central image of the fresco as reconstructed is a bull charging with such force that its front and back legs are in midair. In front of the bull is a person grasping its horns, seemingly about to vault over it. The next person is in mid-vault, upside down, over the back of the bull, and the final person is facing the rear of the animal, arms out, apparently just having dismounted—“sticking the landing,” as they say in gymnastics.

The people on either side of the bull, as reconstructed, bear markers of both male and female gender: they are painted white, which indicates a female figure according to ancient Egyptian gender-color conventions, which we know the Minoans also used. But both characters wear merely a loincloth, which is male dress. The hairstyle (curls at the top with locks falling down the back) is not uncommon in representations of both youthful males and females. Many interpretations of this gender crossing are possible, but there is little evidence to support one over another, unfortunately. At the very least, we can say that the representation of gender in the Late Aegean Bronze Age was fluid.

The person at the center of the action, vaulting over the bull’s back, is painted brown, which indicates male gender according to ancient Egyptian gender-color conventions, and this makes sense considering his loincloth. It is interesting to note that the muscles of all three of the bull leapers, at their thighs and chests, have been very delicately articulated, accentuating their athletic build.

The background of the scene is blue, white, or yellow monochrome, and indicate no architectural context for the activity. Moreover, the seven panels and Gilliéron’s composite reconstruction all show a border of painted richly variegated stones overlapping in patches. So, it seems we are meant to see these scenes as abstracted action within frames, not part of a wider visual field or narrative.

A rite of passage?

The most interesting question about the bull leaping paintings from Knossos is what they might mean. We cannot understand the whole bull-leaping cycle in detail as it is so fragmentary, but we know that it covered a lot of wall space and a considerable amount of resources must have been expended to create it.

As mentioned above, many cultures across space and time have engaged in bull sports, and they all have a few things in common. First, these sports are life-threatening. To race, dance with, leap over, or kill a bull might very well get you killed. Second, these activities are usually performed before a crowd: they are a civic event, publicly presented and recorded in memory. Third, those who participate in these bull activities are often youths at an age when they are passing from childhood into adulthood and the achievement of the bull sport contributes to that passage. Anthropologists refer this sort of activity as a “rite of passage,” which, when witnessed by one’s community, establishes the participant as an adult.

Therefore, we might surmise that the bull leaping scenes from Knossos refer to such a rite of passage ceremony. Many have identified the Central Court (Theatral area) just beyond the west façade of the palace at Knossos as locations where bull-leaping ceremonies might have taken place. We may never know the exact meaning of these paintings, but they continue to resonate with us today—not only because of their beauty and dynamism, but because they represent an activity that is still an important part of many cultures around the world.