3.4.1: Pompeii, an introduction

- Page ID

- 163490

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Pompeii, once called the “City of the Dead,” gives a marvelous sense of day-to-day Roman life.

Preserved under volcanic ash

Pompeii may be famous today, with millions of tourists visiting each year, but in the ancient world It was simply a market and trading town specializing in a fish-based condiment (called garum); other sites on the Bay of Naples were far better known as sumptuous vacation spots.

Pompeii was destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius (a volcano near the Bay of Naples) in 79 C.E. making the town one of the best-preserved examples of a Roman city, and tourists today marvel at the sensation of walking through a real ancient city.

While the volcano took thousands of lives and made the region uninhabitable for centuries, the layers of volcanic ash preserved Pompeii in a manner unparalleled at other ancient Roman sites. Not only have the magnificent temples and villas of the town been preserved, but also one-room workshops, graves of lower-class citizens, and modest take-out restaurants frequented by the hoi polloi. Organic materials like food, clothing, and wood are more often preserved in nearby Herculaneum, because of the differences in volcanic materials covering the two towns. And so, Pompeii, this “city of death” in fact tells us more about daily life in first-century Italy than even the city of Rome itself.

Not always Roman

Pompeii, however, was not always a Roman town. By the mid-sixth century B.C.E. both Etruscans and Greeks had settled in this area, yet their specific contributions to the founding of Pompeii as a city are currently poorly understood since archaeological exploration of the earliest phases of the town have been scarce. The Doric Temple in Pompeii’s Triangular Forum, nevertheless, suggests a stronger Greek than Etruscan presence.

The 5th and 4th centuries B.C.E. at Pompeii were a time of dominance by the Samnites—an indigenous people of south-central Italy who spoke the Oscan language. Their settlement occupied what is now the south-west corner of Pompeii, a site strategically placed at the mouth of the Sarno River near the Bay of Naples. By the middle of the 4th century, the melting-pot of cultures in this region had reached a boiling point, with Greek, Samnite, and Roman residents coming into conflict.

Over the course of the 3rd century B.C.E., Pompeii was one of many Italian towns that came to be dominated by the Romans. This power shift put Pompeii on a path to prosperity and many large, new, public buildings were constructed in the late 3rd century and into the 2nd. This was the time at which the Forum acquired its general footprint and large high-status houses replaced simpler ones.

Pompeii becomes Roman

The years 91-88 B.C.E. were dramatic ones for Pompeii, as it took part in a rebellion against Rome (the Social Wars). Having lost this battle of allied cities against the capital, the Roman general Sulla re-founded the city as a proper Roman colony and settled his army veterans in Pompeii. The existing inhabitants of Pompeii must have resented this move, but when new public buildings, including the Amphitheater, were constructed to meet the needs and desires of the new residents, this resentment may have eased. Later, the period of the early Roman Empire (c. 27 B.C.E.-69 C.E.) was a prosperous one for Pompeii; large, luxurious homes as well as imported goods from around the Mediterranean show up at this time.

The City Plan and its Major Features

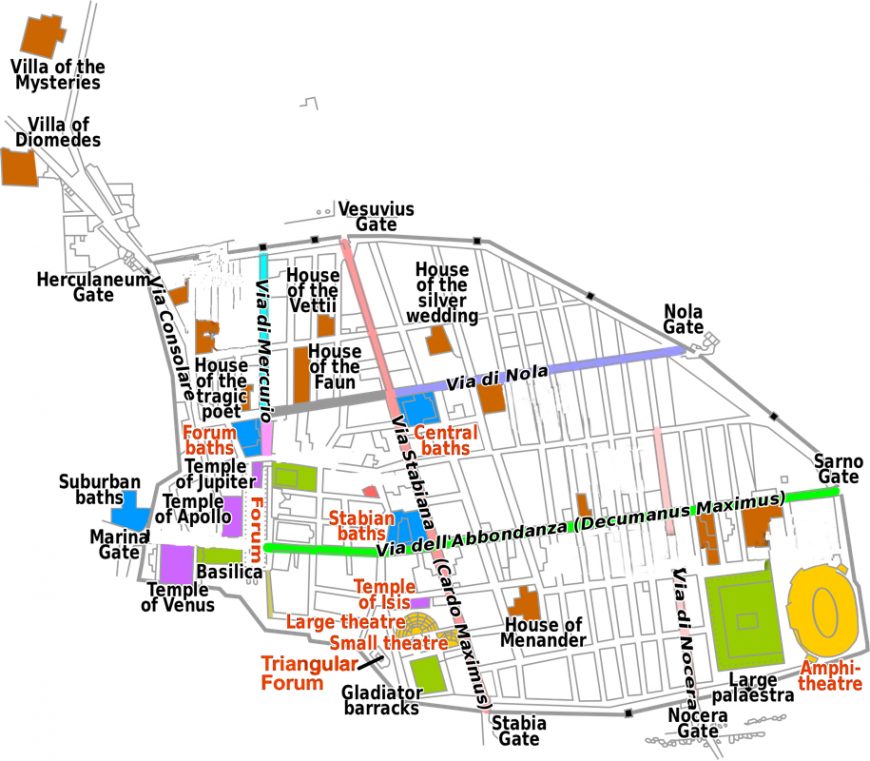

The vast majority of the buildings visible at Pompeii today are from the Roman period, but some earlier features remain. The nucleus of the city in the 6th century B.C.E. was situated on a plateau overlooking the Sarno River at the southwest corner of what became the final “version” of Pompeii, and was organized around sanctuaries dedicated to Apollo and Minerva (or possibly Hercules). This early city had walls and a roughly grid-shaped street plan.

As Pompeii grew in size and population, the city walls were expanded, with gates at the ends of major roads. Slowly, the largely agricultural land inside the walls was built over with homes, places of production, markets, and other urban amenities. The east-west streets (known today by their modern names via della Fortuna, via di Nola, via dell’Abbondanza) and north-south ones (via Stabiana, via di Mercurio) formed the basis for the creation of insulae (city blocks), most of which are generally rectangular and contained a mix of domestic, commercial, and industrial buildings.

The Forum, “theater district,” amphitheater, and baths

Ancient Roman cities were almost never zoned or planned for specific activities. There are two main areas of Pompeii, however, that were loosely organized around a general function. The Forum, at the southwest corner of the city, was the site of various services and structures, and could be considered a sort of “downtown” for Pompeii.

Additionally, a kind of “entertainment district” in the south-central section of Pompeii included two theaters—one open-air, the other smaller and roofed. In these theaters, one could see plays, hear musical performances, and perhaps hold civic or social gatherings. These entertainments differ drastically from those enjoyed in the amphitheater at Pompeii.

Built more than 150 years before the Colosseum in Rome, Pompeii’s facility is the first known Roman amphitheater, where gladiators fought one another or hunted wild animals as a spectacle. It is estimated that between 10,000-15,000 people could be accommodated in Pompeii’s amphitheater. A fresco from a house at Pompeii illustrates in a shorthand way the spectacula (seating area) and arena (playing surface) as well as the velarium (sun shade) of the amphitheater.

As in Rome, Pompeii also had public establishments for bathing. At least five public baths (and scores of private ones within homes) provided not simply a place to get clean, but also opportunities for social interaction and exercise. Communal bathing was a custom for middle- and upper-class Romans; men especially would spend their afternoons in the baths, enjoying heated pools, steam rooms, cold plunge tubs, massages, ball games, and so forth, in the company of their peers and surrounded by beautiful decoration in mosaic, stucco, and sculpture.

Both the Stabian and the Forum Baths were initially constructed with public funds, indicating the extent to which such establishments were considered essential for Pompeii’s residents. Surviving inscriptions, however, indicate that a wealthy citizen could contribute financing for an addition to (or renovation of) the baths, as in the case of a large marble fountain in the caldarium (hot-water room) of the Forum Baths.

An aqueduct fed both private and public baths, although many residents of Pompeii relied on rainwater or abundant wells in the city to supply their water. The high state of preservation at Pompeii provides a view of the city’s water supply, from the aqueduct, through a distribution center at the high northern part of the town, through water towers and public fountains, and into private homes by way of terracotta and lead pipes. The most luxurious homes in Pompeii had fountains decorated with mosaics, sea shells, sculpture, and even frescoes.

The Forum

The religious, political, and commercial center of any Roman city was its forum. A kind of town center existed in the earliest phases of Pompeii at its southwest corner, but the forum only received monumental form and decoration in the 2nd century B.C.E. At that time, the Temple of Jupiter (eventually the Capitolium), Macellum (market), and Basilica (law court) were constructed and the open piazza of the forum was paved with stone. Statues of illustrious Pompeians, civic benefactors, and the imperial family stood under the forum colonnades and in the open areas of the piazza as well as in two buildings dedicated to the worship of divinized emperors—the Imperial Cult Building and the Sanctuary of Augustus (these statues are now entirely lost, save for their bases).

Religious Life at Pompeii

The forum provided ample opportunity for the citizens of Pompeii to worship their various gods as well as divinized members of the imperial family. Temples to Apollo and Venus stood just outside the forum proper and represent both early (6th century B.C.E.) and later (post-80 B.C.E.) historical building periods, respectively. Smaller temples throughout Pompeii honored Jupiter, Asclepius, and Minerva (in the Greek temple in the Triangular Forum). Even more modest shrines stood at important crossroads and inside the atria of private homes. These lararia, dedicated to somewhat mysterious guardian deities called Lares, were decorated with paintings and received small votive offerings.

A small, yet impressive temple to the Egyptian goddess Isis stands just to the north of the Large Theater. The cult of Isis had been introduced to Italy as early as the 2nd century B.C.E. and was apparently very popular at Pompeii, as indicated by the sumptuous painted stucco decoration of the precinct walls, Fourth Style wall paintings, a marble statue of Isis herself (now in the Naples Archaeological Museum), and abundant finds of votive offerings, some of which were imported from Egypt.

Death and Burial

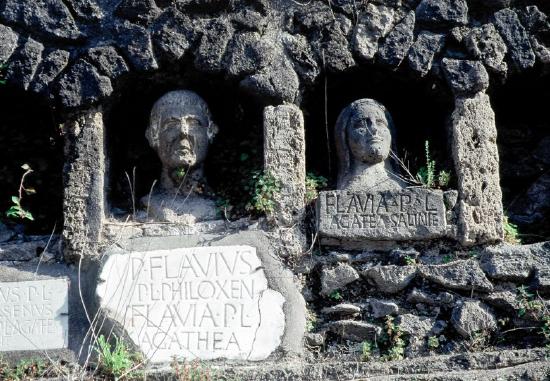

Because of the circumstances of its destruction, Pompeii often encourages macabre interest in those who perished in the city during the 79 C.E. eruption of Vesuvius. Yet for centuries, citizens of Pompeii had been solemnly commemorating their dead with sometimes elaborate tombs and costly grave goods. Longstanding traditions among ancient Mediterranean cultures generally prohibited burials within a city’s walls and Pompeii followed that tradition. The roads leading from the various city gates are lined on both sides with tombs—some were for individual burials while others were designed for multiple occupancy (usually of the lower classes or freed slaves). The most prestigious burials can be recognized both by their forms and by their location just outside a city gate, where they could be seen by as many passers-by as possible.

There was no standard shape for Roman tombs and Pompeiian funerary monuments could be decorated with statues of the deceased, pseudo-autobiographical relief sculpture, wall paintings, and even functional features like benches. Multiple-occupancy “house tombs,” popular in the last century of Pompeii’s existence, contained the cremated remains of various members of a single family or social group. These lower-cost tombs had brief inscriptions about the deceased persons and small niches held the stone, ceramic, or glass ash urns.

An open-air museum

At the time of the destruction of the city, an estimated 15,000 people lived in Pompeii. As many as 2,000 died in the ash and toxic gases of Vesuvius’ eruption in 79 C.E. The city today is an open-air museum dedicated to the experience of walking through an ancient Roman town. And while the houses and wall paintings from the last phase of Pompeii are what attracts the most visitors, the city’s complex social and building history, as well as the urban infrastructure, are worth noting as well.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Reconstruction of the house of Caecilius Iucundus from Lund University