3.2.6: Forum Romanum (The Roman Forum)

- Page ID

- 163483

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\)

The heart of ancient Rome, the Forum Romanum was the monumental center of religious, political, and social life.

In his play Curculio, the Latin playwright Plautus offers perhaps one of the most comprehensive and insightful descriptions of the Forum Romanum ever written (ll. 466-482). In his summary, Plautus gives the reader the sense that one could find just about every sort of person in the forum—from criminals and hustlers to politicians and prostitutes. His summary reminds us that in the city of Rome the Forum Romanum was the key political, ritual, and civic center. Located in a valley separating the Capitoline and Palatine Hills, the Forum developed from the earliest times and remained in use after the city’s eventual decline; during that span of time the forum witnessed the growth and eventual contraction of the city and her empire. The archaeological remains of the Forum Romanum itself continue to provide important insights into the phases and processes associated with urbanism and monumentality in ancient Rome.

Earliest history: from necropolis to civic space

Situated astride the Tiber river, the site of Rome is noted for its low hills that are separated by deeply cut valleys. The hilltops became the focus of settlement beginning in the Early Iron Age; the development of the settlement continued during the first millennium B.C.E., with the traditional Roman account holding that the city herself was founded in 753 B.C.E. (Livy 1.6)

The traditional foundation narrative holds that one of the first acts of Romulus, the city’s eponymous founder, was to establish a fortification wall around the Palatine Hill, the site of his new settlement. The Capitoline Hill, opposite the Palatine, emerged as the city’s citadel (arx) and site of the poliadic cult of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, among others (poliadic: the chief civic cult of an ancient city, derived from the Greek word “polis”).

Iron Age populations had used the marshy valley separating the Palatine and Capitoline hills as a necropolis (a large ancient cemetery), but the burgeoning settlement of archaic Rome had need of communal space and the valley was repurposed from a necropolis to a usable space. This required several transformations, both of human activity and the natural environment. Burial activity had to be transferred elsewhere; for this reason the main necropolis site shifted to the far side of the Esquiline Hill.

Addressing the problems of seasonal rains and flooding proved more challenging—the valley required a landfill project as well as the construction of a drainage canal to manage standing water. Since the Tiber river tended to leave its banks regularly, the valley was prone to significant flooding, as a low saddle of land known as the Velabrum connects the forum valley to the riverine zone. As coring studies conducted by Albert J. Ammerman have shown, a deliberate landfill project deposited fill in the forum valley in order to create usable, dry levels during the sixth century B.C.E. Twentieth century excavators, including Giacomo Boni and Einar Gjerstad, revealed important remains of Iron Age burials that pre-dated the establishment of the forum valley as a civic space; in particular the necropolis in the area known as the Sepulcretum along the Sacra Via (“Sacred Way,” the main sacred processional road of the city) has been extensively studied and published. The investigations of the burials themselves, and the patterns they followed, have allowed archaeologists to understand not only funeral customs but also social dynamics during Rome’s proto-urban phases.

This major investment in the creation of civic space and the organization of labor also provides important information about the socio-economic structure of early Rome (Livy 1.59.9). The drainage canal eventually came to have a vaulted covering and was known as the Cloaca Maxima or “Great Drain.” One of the clear outcomes of these civic investments was the creation of a usable space that came to be a civic focus for activities in many spheres, especially political and sacred functions.

Temples and sacred buildings

From the Early Republican period the forum space saw the construction of key temples. One of the most prominent early temples is the Temple of Saturn (often considered the earliest of the temples in the Forum Romanum), the first iteration of which dates c. 498 B.C.E. The temple was dedicated to Saturn, the god of agriculture, and housed the state treasury. The temple was rebuilt in 42 B.C.E. and again after 283 C.E. Another early Republican temple is the Temple of the Castors (a.k.a. Temple of Castor and Pollux) that was completed in 484 B.C.E. and was dedicated to the Gemini who had aided the Romans at the Battle of Lake Regillus in 496 B.C.E. The temple had several construction phases. The Sacra Via passed along the forum square en route to the Capitoline Hill and the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. This sacred route was used for certain state-level ceremonies, especially the celebration of the victory ritual known as the Roman triumph.

Two other early, sacred buildings are important to note. These are the Regia or “king’s house” and the Temple of Vesta, both located on the downward slope of the Palatine Hill near the point where it reaches the edge of the Forum Romanum proper. Both of these sacred buildings are quite ancient and had many building phases, making it difficult to refine the chronology of the earliest phases. The Regia served as a ceremonial home for the king—later passing into the ownership of the pontifex maximus (principal state-level priesthood) once the kings had been expelled—and consisted of an irregularly planned suite of rooms surrounding a courtyard. The sixth century B.C.E. phase was decorated with painted plaques of architectural terracotta, clearly indicating both elite function and investment. Across the way was the Temple of Vesta, focused on the maternal elements of the archaic state as well as safeguarding the cult of Vesta and the sacred, eternal hearth flame of the Roman people. Both the Regia and the Temple of Vesta developed from crude structures in earlier phases to stone-built architecture in later phases. The Severan family carried out the final significant restoration of the Temple of Vesta in 191 C.E.

Meeting spaces

Important meeting spaces for political bodies emerged at the northwest side of the forum, namely a pair of complexes known as the Curia and Comitium. The Curia served as the council house for the Roman Senate, although the Senate could convene in any inaugurated space (i.e. a space ritually demarcated by Roman priests). The Curia emerged perhaps in the seventh century B.C.E., although little is known about its earliest phases. The surviving Curia is an imperial rebuilding of the Late Republican phase known as the Curia Julia, since Julius Caesar was its architectural patron. The Comitium was a tiered space that lay in front of the Curia that served as an open-air meeting space for public assemblies. Little of the Comitium remains today but it was a key architectural complex for political and sacred events during the time of the Roman Republic.

From Republic to Empire

During the fourth and third centuries B.C.E. the Forum Romanum certainly continued to develop, but material remains of large-scale architecture have proven elusive and thus our understanding of the space during those centuries is less clear than in other periods. One middle Republican development is the continued elaboration of the Rostra, the platform from which orators would speak to those assembled in the forum square. This monument would continue to develop over time and took its name from the prows (rostra) of defeated enemy warships that were mounted on its façade.

The later second and first centuries B.C.E., the Late Republican period, witnessed many changes in the city and in the Forum Romanum. The successes of Rome and her growing empire during the second and first centuries B.C.E. led to a great deal of monumental construction in the city, including in the Forum Romanum itself. It was during this Late Republican phase that Rome became a metropolitan center, equipped with the monumental architecture that could compete with—if not eclipse—that of the foreign powers Rome had tamed during the Punic Wars and those against the Hellenistic kingdoms of the eastern Mediterranean. In particular the Romans established a tradition of constructing monuments commemorating famous men who had achieved great success in military and public careers. The first of these was the Columna Rostrata that marked the naval victory of Caius Duilius at the naval battle of Mylae in 260 B.C.E. The Roman interest in monumental, commemorative monuments, now referred to as triumphal arches, would soon follow. The first of these, the Fabian arch (fornix Fabianus), was dedicated on the Sacra Via toward the eastern end of the Forum Romanum in 121 B.C.E., commemorating the military victories (and family) of Quintus Fabius Allobrogicus (Cicero pro Planc. 17). While the Fabian monument is no longer extant, its construction established a tradition (and a traditional form) for official commemorative and honorific monuments in the context of Roman public art.

The Basilica

The second century B.C.E. saw the creation and introduction of a unique Roman building type, the basilica. The basilica was a columnar hall that often had a multi-purpose use—from law courts to commerce to entertainments. Roman planners came to prefer them for lining the long sides of open squares, in a way not dissimilar from the Greek stoa. The sources claim that the Basilica Porcia (c. 184 B.C.E.) was the first basilica built at Rome, although no trace of it remains. The Basilica Porcia served as an office for the tribunes of the plebs. Other, more elaborate basilicae were soon to be built, including the famous Basilica Aemilia, first built in 179 B.C.E., and remodeled from c. 55 to 34 B.C.E. as the Basilica Paulli. Restored again after a fire in 14 B.C.E., the famous basilica was deemed by Pliny the Elder to be one of the three most beautiful monuments in Rome (Plin. HN 36.102.5)

Imperial period

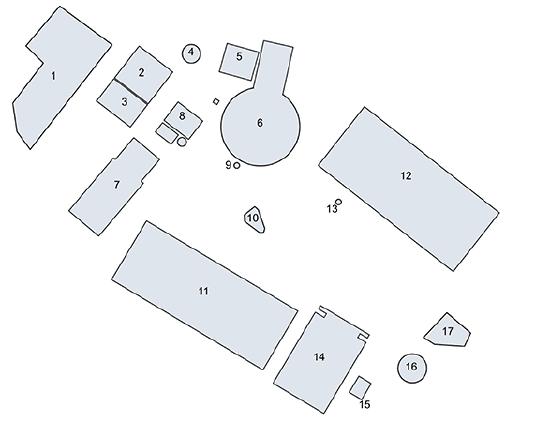

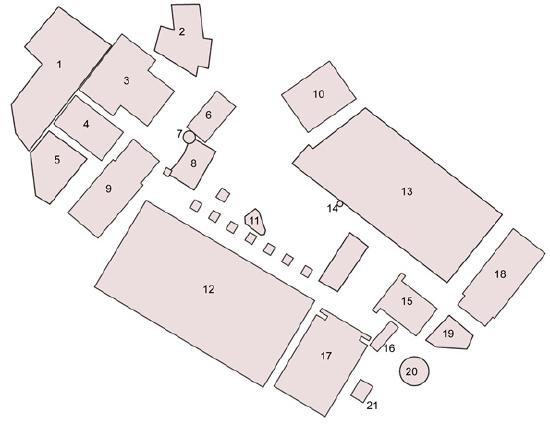

The advent of the principate of Augustus (27 B.C.E. – 14 C.E.) brought about additions and renovations to the Forum Romanum. With the deification of Julius Caesar, Augustus’ adoptive father, a temple dedicated to Caesar’s cult (templum divi Iulii) was constructed on the edge of the forum square (15 in the diagram below).

Augustus restored existing buildings, completed incomplete projects, and added commemorative projects to celebrate his own accomplishments and those of his family members. In this latter group, the Arch of Augustus (#16 above) and the Porticus of Caius and Lucius are notable. The former was a triumphal arch celebrating significant military and diplomatic accomplishments of the emperor, while the latter honored the emperor’s grandsons.

Augustus also followed Julius Caesar in creating yet another new forum space beyond the Forum Romanum that was named the Forum of Augustus. (dedicated in 2 B.C.E.). These new Imperial Fora in some cases provided additional space and, in turn, shifted attention away from the Forum Romanum.

During the Imperial period the Forum Romanum itself saw only sporadic new construction, although the maintenance of the existing structures would have provided a pressing and ongoing obligation. Just beyond the limit of the forum proper the second century C.E. temple of Antoninus Pius and his wife Faustina was constructed in 141 C.E. (and then modified in 161 C.E. following the emperor’s death).

Coming to power at the end of the second century C.E., the Severan family erected a triple-bay triumphal arch commemorating the victories of emperor Septimius Severus (reigned 193-211 C.E.) at the northwestern corner of the forum square. The third century C.E. saw rebuilding of structures and monuments that had been damaged by fire, including the rebuilding of the Curia Julia by the emperor Diocletian in the late third century C.E. following a fire in 283 C.E.

Decline

Declining imperial fortunes led inevitably to urban decay at Rome. After the Severan and Tetrarchic building programs of the third century C.E. and Constantinian investment in the early fourth century C.E., the forum and its environs began to decline and decay. Constantine I officially relocated the administrative center of the Roman world to Constantinople in 330 C.E. and Theodosius I suppressed all “pagan” religions and ordered temples shut permanently in 394 C.E. These changes, coupled with population decline, spelled the gradual demise of spaces like the Forum Romanum. Roman monuments were cannibalized for building materials and open, unused spaces were re-purposed—sometimes as ad hoc dwellings and other times for the deposition of rubbish and fill. Thus the forum slowly yielded its sacro-civic functions to more mundane concerns like pasturage—in fact it eventually came to be known as the “Campo Vaccino” (cow field).

The beauty of the ruins

The monument that is considered to be the final ancient structure erected in the Forum Romanum is a re-purposed monumental column set in place by the emperor Phocas in August of 608 C.E. The anonymous Einsiedeln itinerary, written in the eighth century C.E., mentions a general state of decay in the forum. A major earthquake in 847 C.E. wreaked considerable damage on remaining Roman monuments in the forum and in its environs. During the Middle Ages ancient structures provided reusable buildings materials, as well as reusable foundations, for Medieval structures.

The ruins themselves provided endless inspiration for artists, including painters the likes of Canaletto who became interested in the romanticism of the ruins of the ancient city as well as for cartographers and engravers the likes of G. B. Piranesi and G. Vasi, among others, who created views of the ruins themselves and restored plans of the ancient city.

Interpretation

The Forum Romanum, despite being a relatively small space, was central to the function and identity of the city of Rome (and the wider Roman empire). The Forum Romanum played a key role in creating a communal focal point, one toward which various members of a diverse socio-economic community could gravitate. In that centralized space community rituals that served a larger purpose of group unity could be performed and observed and elites could reinforce social hierarchy through the display of monumental art and architecture. These devices that could create and continually reinforce not only a sense of community belonging but also the existing social hierarchy were of vital importance in archaic states. Even as the Forum Romanum changed over time, it remained an important space. After a series of emperors chose to build new forum complexes (the Imperial Fora) adjacent to the Forum Romanum, it retained its symbolic importance, especially considering that, as a people, ancient Romans were incredibly loyal to ancestral practices and traditions.

Rediscovery and excavation

Many of the monuments of the Forum Romanum, along with ancient occupation levels, gradually disappeared from view. Systematic exploration and study began under archaeologist Carlo Fea who started to clear the area near the Arch of Septimius Severus in 1803. Study continued during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with prominent scholars including Rodolfo Lanciani, Giacomo Boni, Einar Gjerstad, and Andrea Carandini, among others, leading major campaigns. Study and excavation—as well as the hugely important obligation of preservation—continue in the Forum Romanum today. The bulk of the forum is accessible to visitors who have the opportunity to experience one of the great documents of urban archaeology.

Additional resources:

A. J. Ammerman, “On the Origins of the Forum Romanum,” American Journal of Archaeology vol. 94, no. 4, 1990, pp. 627-45.

A. J. Ammerman, “The Comitium in Rome from the Beginning.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 100, no. 1, 1996. pp. 121-36.

P. Carafa, Il comizio di Roma dalle origini all’età di Augusto (Rome: “L’Erma” di Bretschneider, 1998).

A. Carandini and P. Carafa, eds., Atlante di Roma antica: biografia e ritratti della città, 2 v. (Milan: Electa, 2012).

A. Claridge, Rome: an Archaeological Guide 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

F. Coarelli, Il foro romano, 2 v. (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 1983-1992).

F. Coarelli, Rome and Environs: an Archaeological Guide, trans. James J. Clauss and Daniel P. Harmon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

E. Gjerstad, Early Rome, 7 v. (Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup, 1953-1973).

C. Hülsen and J. B. Carter, The Roman forum: its history and its monuments, 2nd ed. (Rome: Stechert, 1906).

R. Krautheimer, Rome, profile of a city, 312-1308 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980).

R. Krautheimer, Three Christian capitals: topography and politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983).

G. Lugli, Fontes ad topographiam veteris urbis Romae pertinentes. Colligendos atque edendos curavit Iosephus Lugli, 8 v. (Rome: Università di Roma, Istituto di topografia antica, 1952-1965).

G. Lugli, The Roman Forum and Palatine (Rome: Bardi, 1961).

S. B. Platner and T. Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1929).

L. Richardson, jr., A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992).

J. Sewell, The formation of Roman urbanism, 338-200 B.C.: between contemporary foreign influence and Roman tradition (Journal of Roman archaeology Supplementary series; 79), (Portsmouth RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 2010).

J. E. Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988).

E. M. Steinby, ed., Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, 6 v. (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 1993-2000).

D. Watkin, The Roman Forum (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009).

A. Ziółkowski, Sacra Via: twenty years after (Journal of Juristic Papyrology, Supplement; 3), (Warsaw: Fundacja im. Rafała Taubenschlag, 2004).

Roman Forum and Palatine Hill