3.2.1: An introduction to ancient Roman architecture

- Page ID

- 163478

Roman architecture was unlike anything that had come before. The Persians, Egyptians, Greeks and Etruscans all had monumental architecture. The grandeur of their buildings, though, was largely external. Buildings were designed to be impressive when viewed from outside because their architects all had to rely on building in a post-and-lintel system, which means that they used two upright posts, like columns, with a horizontal block, known as a lintel, laid flat across the top. A good example is this ancient Greek Temple in Paestum, Italy.

Since lintels are heavy, the interior spaces of buildings could only be limited in size. Much of the interior space had to be devoted to supporting heavy loads.

Roman architecture differed fundamentally from this tradition because of the discovery, experimentation and exploitation of concrete, arches and vaulting (a good example of this is the Pantheon, c. 125 C.E.). Thanks to these innovations, from the first century C.E. Romans were able to create interior spaces that had previously been unheard of. Romans became increasingly concerned with shaping interior space rather than filling it with structural supports. As a result, the inside of Roman buildings were as impressive as their exteriors.

Materials, methods and innovations

Long before concrete made its appearance on the building scene in Rome, the Romans utilized a volcanic stone native to Italy called tufa to construct their buildings. Although tufa never went out of use, travertine began to be utilized in the late 2nd century B.C.E. because it was more durable. Also, its off-white color made it an acceptable substitute for marble.

Marble was slow to catch on in Rome during the Republican period since it was seen as an extravagance, but after the reign of Augustus (31 B.C.E. – 14 C.E.), marble became quite fashionable. Augustus had famously claimed in his funerary inscription, known as the Res Gestae, that he “found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble” referring to his ambitious building campaigns.

Roman concrete (opus caementicium), was developed early in the 2nd c. BCE. The use of mortar as a bonding agent in ashlar masonry wasn’t new in the ancient world; mortar was a combination of sand, lime and water in proper proportions. The major contribution the Romans made to the mortar recipe was the introduction of volcanic Italian sand (also known as “pozzolana”). The Roman builders who used pozzolana rather than ordinary sand noticed that their mortar was incredibly strong and durable. It also had the ability to set underwater. Brick and tile were commonly plastered over the concrete since it was not considered very pretty on its own, but concrete’s structural possibilities were far more important. The invention of opus caementicium initiated the Roman architectural revolution, allowing for builders to be much more creative with their designs. Since concrete takes the shape of the mold or frame it is poured into, buildings began to take on ever more fluid and creative shapes.

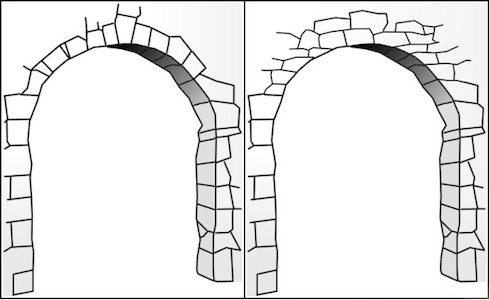

The Romans also exploited the opportunities afforded to architects by the innovation of the true arch (as opposed to a corbeled arch where stones are laid so that they move slightly in toward the center as they move higher). A true arch is composed of wedge-shaped blocks (typically of a durable stone), called voussoirs, with a key stone in the center holding them into place. In a true arch, weight is transferred from one voussoir down to the next, from the top of the arch to ground level, creating a sturdy building tool. True arches can span greater distances than a simple post-and-lintel. The use of concrete, combined with the employment of true arches allowed for vaults and domes to be built, creating expansive and breathtaking interior spaces.

Roman architects

We don’t know much about Roman architects. Few individual architects are known to us because the dedicatory inscriptions, which appear on finished buildings, usually commemorated the person who commissioned and paid for the structure. We do know that architects came from all walks of life, from freedmen all the way up to the Emperor Hadrian, and they were responsible for all aspects of building on a project. The architect would design the building and act as engineer; he would serve as contractor and supervisor and would attempt to keep the project within budget.

Building types

Roman cities were typically focused on the forum (a large open plaza, surrounded by important buildings), which was the civic, religious and economic heart of the city. It was in the city’s forum that major temples (such as a Capitoline temple, dedicated to Jupiter, Juno and Minerva) were located, as well as other important shrines. Also useful in the forum plan were the basilica (a law court), and other official meeting places for the town council, such as a curia building. Quite often the city’s meat, fish and vegetable markets sprang up around the bustling forum. Surrounding the forum, lining the city’s streets, framing gateways, and marking crossings stood the connective architecture of the city: the porticoes, colonnades, arches and fountains that beautified a Roman city and welcomed weary travelers to town. Pompeii, Italy is an excellent example of a city with a well preserved forum.

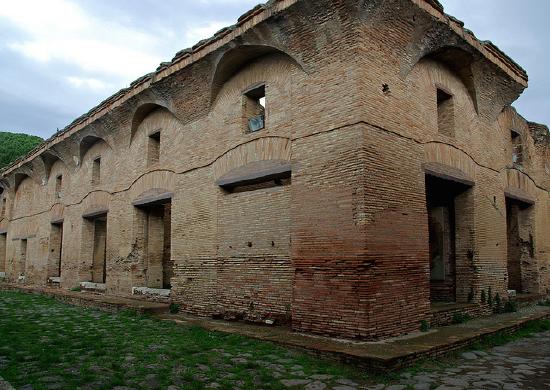

Romans had a wide range of housing. The wealthy could own a house (domus) in the city as well as a country farmhouse (villa), while the less fortunate lived in multi-story apartment buildings called insulae. The House of Diana in Ostia, Rome’s port city, from the late 2nd c. C.E. is a great example of an insula. Even in death, the Romans found the need to construct grand buildings to commemorate and house their remains, like Eurysaces the Baker, whose elaborate tomb still stands near the Porta Maggiore in Rome.

The Romans built aqueducts throughout their domain and introduced water into the cities they built and occupied, increasing sanitary conditions. A ready supply of water also allowed bath houses to become standard features of Roman cities, from Timgad, Algeria to Bath, England. A healthy Roman lifestyle also included trips to the gymnasium. Quite often, in the Imperial period, grand gymnasium-bath complexes were built and funded by the state, such as the Baths of Caracalla which included running tracks, gardens and libraries.

Entertainment varied greatly to suit all tastes in Rome, necessitating the erection of many types of structures. There were Greek style theaters for plays as well as smaller, more intimate odeon buildings, like the one in Pompeii, which were specifically designed for musical performances. The Romans also built amphitheaters—elliptical, enclosed spaces such as the Colloseum—which were used for gladiatorial combats or battles between men and animals. The Romans also built a circus in many of their cities. The circuses, such as the one in Lepcis Magna, Libya, were venues for residents to watch chariot racing.

The Romans continued to perfect their bridge building and road laying skills as well, allowing them to cross rivers and gullies and traverse great distances in order to expand their empire and better supervise it. From the bridge in Alcántara, Spain to the paved roads in Petra, Jordan, the Romans moved messages, money and troops efficiently.

Republican period

Republican Roman architecture was influenced by the Etruscans who were the early kings of Rome; the Etruscans were in turn influenced by Greek architecture. The Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill in Rome, begun in the late 6th century B.C.E., bears all the hallmarks of Etruscan architecture. The temple was erected from local tufa on a high podium and what is most characteristic is its frontality. The porch is very deep and the visitor is meant to approach from only one access point, rather than walk all the way around, as was common in Greek temples. Also, the presence of three cellas, or cult rooms, was also unique. The Temple of Jupiter would remain influential in temple design for much of the Republican period.

Drawing on such deep and rich traditions didn’t mean that Roman architects were unwilling to try new things. In the late Republican period, architects began to experiment with concrete, testing its capability to see how the material might allow them to build on a grand scale.

The Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia in modern day Palestrina is comprised of two complexes, an upper and a lower one. The upper complex is built into a hillside and terraced, much like a Hellenistic sanctuary, with ramps and stairs leading from the terraces to the small theater and tholos temple at the pinnacle. The entire compound is intricately woven together to manipulate the visitor’s experience of sight, daylight and the approach to the sanctuary itself. No longer dependent on post-and-lintel architecture, the builders utilized concrete to make a vast system of covered ramps, large terraces, shops and barrel vaults.

Imperial period

The Emperor Nero began building his infamous Domus Aurea, or Golden House, after a great fire swept through Rome in 64 C.E. and destroyed much of the downtown area. The destruction allowed Nero to take over valuable real estate for his own building project; a vast new villa. Although the choice was not in the public interest, Nero’s desire to live in grand fashion did spur on the architectural revolution in Rome. The architects, Severus and Celer, are known (thanks to the Roman historian Tacitus), and they built a grand palace, complete with courtyards, dining rooms, colonnades and fountains. They also used concrete extensively, including barrel vaults and domes throughout the complex. What makes the Golden House unique in Roman architecture is that Severus and Celer were using concrete in new and exciting ways; rather than utilizing the material for just its structural purposes, the architects began to experiment with concrete in aesthetic modes, for instance, to make expansive domed spaces.

Nero may have started a new trend for bigger and better concrete architecture, but Roman architects, and the emperors who supported them, took that trend and pushed it to its greatest potential. Vespasian’s Colosseum, the Markets of Trajan, the Baths of Caracalla and the Basilica of Maxentius are just a few of the most impressive structures to come out of the architectural revolution in Rome. Roman architecture was not entirely comprised of concrete, however. Some buildings, which were made from marble, hearkened back to the sober, Classical beauty of Greek architecture, like the Forum of Trajan. Concrete structures and marble buildings stood side by side in Rome, demonstrating that the Romans appreciated the architectural history of the Mediterranean just as much as they did their own innovation. Ultimately, Roman architecture is overwhelmingly a success story of experimentation and the desire to achieve something new.

Additional resources:

James C. Anderson Jr., Roman Architecture and Society (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

Diana Kleiner, Roman Architecture: A Visual Guide (Kindle) (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014).

William J. MacDonald, The Architecture of the Roman Empire, vol. I: An Introductory Study (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982).

Frank Sear, Roman Architecture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983).

J.B. Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning: