12.4: Banality and Kitsch

- Page ID

- 67110

Banality and kitsch

Artists deploy mass-produced images to critique the impact of consumer culture and Modernism's disengagement with the everyday world.

1980 - now

Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living

by SAL KHAN, DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991

Jeff Koons, Pink Panther

Banality

Imagine walking into an art gallery and seeing overgrown toys, or cartoon characters presented as sculpture. If, in 1988, you had wandered into the Sonnabend Gallery on West Broadway in New York City, this is indeed what you would have witnessed: it was an exhibition entitled “Banality” by New York artist Jeff Koons presenting some twenty sculptures in porcelain and polychromed wood. The work certainly strikes as an affront to taste: the sculptures are highly polished and gleaming. The colors—muted pale blue, pink, lavender, green and yellowish gold—seem to belong to the 1950s and 60s. The glossy textures look garish and factory-made, surfaces one associates with inexpensive commercial art. One would almost want to call these sculptures “figurines” were it not for their size. To add to this catalogue of horrors, the artist had farmed out the actual production to German and Italian artisans who made each work in triplicate! “Banality” thus debuted simultaneously in New York, Chicago, and Cologne.

A glazed porcelain statue entitled Pink Panther belongs to that body of work. It depicts a smiling, bare-breasted, blond woman scantily clad in a mint-green dress, head tilted back and to the left as if addressing a crowd of onlookers. The figure is based on the 1960s B-list Hollywood star Jayne Mansfield—here she clutches a limp pink panther in her left hand, while her right hand covers an exposed breast. From behind one sees that the pink panther has its head thrown over her shoulder and wears an expression of hapless weariness. It too is a product of Hollywood fantasy—the movie of the same name debuted the cartoon character in 1963. The colors are almost antiquated; do they harken back to the popular culture of a pre-civil rights era as a politically regressive statement of nostalgia? And what about the female figure—posed in a state of deshabille (carelessly and partially undressed)? At a time of increased feminist presence in the still male-dominated art world this could only be perceived as a rearguard move. Or was Koons—a postmodern provocateur like no other—simply parodying male authority as he had done in some of his other work?

Postmodernism: the artist as critic of mass culture

Provocation is a mainstay of the modernist avant-gardes reaching at least as back as far as when Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain of 1917, an ordinary urinal, was proposed as an artwork (“avant-garde” refers to artists whose work challenges established ideas). But whereas Duchamp eventually accrued near-mythical status, that same critical reception for Koons was not forthcoming—in fact, he would become one of the first artists of this period to achieve a level of success that depended more on the art market than on art criticism. He is still reviled. Only recently a review described Koons as “Duchamp with lots of ostentatious trimmings.”1 It’s easy to see why he has continued to provoke: the postmodern 1980s inaugurated the contemporary sense of the artist as a critical and serious interrogator of mass culture and mass media. Cindy Sherman, one of the most prominent artists of that period, made photographs of herself that paraded the clichés of femininity before an audience that consumed critical theory about the constructed nature of reality and the oppressive manipulations of mass media. Her work was understood as a deconstruction (shorthand for the examination and analysis of the elements) of gender stereotypes. Another prominent postmodern artist of the period, Krzysztof Wodcizko, used high-powered projectors to cast politically charged imagery onto corporate façades after dark—imagery that often pointed to economic and social contradictions and prompted public discourse within an ephemeral and often provocative, public space.

Artists—postmodern artists—were supposed to counter the banality of evil that lurked behind public and popular culture, not giddily revel in it as Koons seemed to do. There appeared to be nothing serious about any of the works in the “Banality” exhibition: a life-sized bust of pop icon Michael Jackson and his pet monkey Bubbles; a ribbon-necked pig—especially egregious—in polychromed wood escorted by cherubic youths, two of which are winged. And of course Pink Panther, a work that seemed destined to insult rather than inform. It all seemed like kitsch posing as high art.

Kitsch

What is kitsch? The American art critic Clement Greenberg once defined it as the opposite of what a truly progressive, avant-garde modernism embodied. Greenberg advocated for a modern art that was true to its materials, such as the gestural abstractions of New York School artists like Jackson Pollock, who splattered and spilled paint in abstract fashion on unprimed canvas—declaring a direct creative confrontation that was raw and honest. Kitsch, a word of German origin, refers to mass-produced imagery designed to please the broadest possible audience with objects of questionable taste (think of objects and images with popular, sentimental subject matter and style). Postmodern art attacked Greenberg’s influential theory of modern art, creating images in direct opposition to modernism. While modernism championed painting, form and originality, postmodernism foregrounded photography, subject matter, and the reproduction, and responded to modernism’s search for the profound by presenting the quotidian and banal aspects of experience. Postmodernism grounded the rarified atmosphere of genius that was prevalent in modernism in the politics of everyday life.

But postmodernism stopped short of fully embracing kitsch by insisting on a degree of self-aware critical distance. This is where Koons found a fault line that he fully exploited with works like Pink Panther. Hummel figurines and other popular collector’s items are the basis for the art in “Banality.” Koons rendered these saccharine and sentimental little figural groupings—cartoonish emblems of childhood innocence—at a life-size scale as an assault upon sincerity but also as an assault upon taste, and it is here that even the most daring of postmodern advocates drew a line in the sand. Like the modernist distinction between art and an everyday object drawn by Greenberg, Pink Panther challenged the distinction between an ironic appropriation of a mass-culture object and the object itself (seemingly without critical distance) thereby challenging the whole critical enterprise of postmodernism itself.

1. Jed Perl, “The Cult of Jeff Koons,” The New York Review of Books, September 25, 2014

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People)

A Non-Celebration

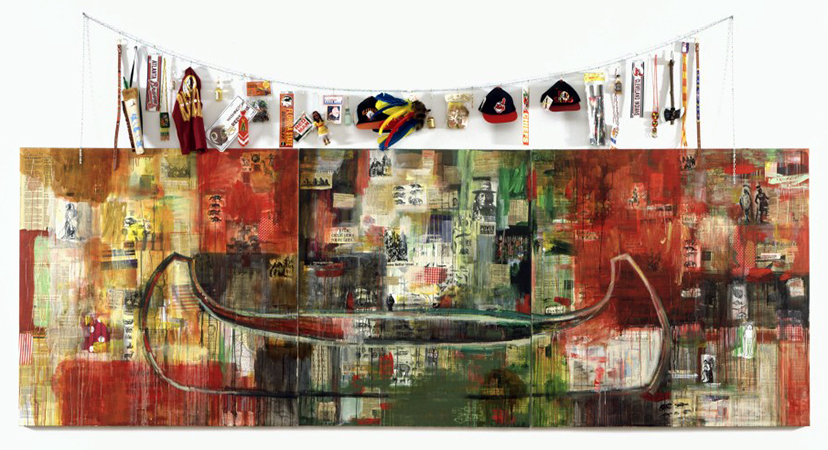

As a response to the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in North America in 1992, the artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Indian Nation, created a large mixed-media canvas called Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People). Trade, part of the series “The Quincentenary Non-Celebration,” illustrates historical and contemporary inequities between Native Americans and the United States government.

Trade references the role of trade goods in allegorical stories like the acquisition of the island of Manhattan by Dutch colonists in 1626 from unnamed Native Americans in exchange for goods worth 60 guilders or $24.00. Though more apocryphal than true, this story has become part of American lore, suggesting that Native Americans had been lured off their lands by inexpensive trade goods. The fundamental misunderstanding between the Native and non-Native worlds—especially the notion of private ownership of land—underlies Trade. Smith stated that if Trade could speak, it might say: “Why won’t you consider trading the land we handed over to you for these silly trinkets that so honor us? Sound like a bad deal? Well, that’s the deal you gave us.”1

For Trade, Smith layered images, paint, and objects on the surface of the canvas, suggesting layers of history and complexity. Divided into three large panels, the triptych (three part) arrangement is reminiscent of a medieval altarpiece. Smith covered the canvas in collage, with newspaper articles about Native life cut out from her tribal paper Char-Koosta, photos, comics, tobacco and gum wrappers, fruit carton labels, ads, and pages from comic books, all of which feature stereotypical images of Native Americans. She mixed the collaged text with photos of deer, buffalo, and Native men in historic dress holding pipes with feathers in their hair, and an image of Ken Plenty Horses—a character from one of Smith’s earlier pieces, the Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by US Government from 1991-92.

She applied blocks of white, yellow, green, and especially red paint over the layer of collaged materials. The color red had multiple meanings for Smith, referring to her Native heritage as well as to blood, warfare, anger, and sacrifice. With the emphasis on prominent brushstrokes and the dripping blocks of paint, Smith cited the Abstract Expressionist movement from the 1940s and 50s with raw brushstrokes describing deep emotions and social chaos. For a final layer, she painted the outline of an almost life-sized canoe. Canoes were used by Native Americans as well as non-Native explorers and traders in the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth century to travel along the waterways of North America. The canoe suggests the possibility of trade and cultural connections—though this empty canoe is stuck, unable to move.

Above the canvas, Smith strung a clothesline from which she dangled a variety of Native-themed toys and souvenirs, especially from sports teams with Native American mascots. The items include toy tomahawks, a child’s headdress with brightly dyed feathers, Red Man chewing tobacco, a Washington Redskins cap and license plate, a Florida State Seminoles bumper sticker, a Cleveland Indian pennant and cap, an Atlanta Braves license plate, a beaded belt, a toy quiver with an arrow, and a plastic Indian doll. Smith offers these cheap goods in exchange for the lands that were lost, reversing the historic sale of land for trinkets. These items also serve as reminders of how Native life has been commodified, turning Native cultural objects into cheap items sold without a true understanding of what the original meanings were.

The Artist

The artist was born on January 15, 1940, at the St. Ignatius Jesuit Missionary on the Reservation of the Flathead Nation. Raised by her father, a rodeo rider and horse trader, Smith was one of eleven children. Her first name comes from the French word for “yellow” (jaune), a reminder of her French-Cree ancestors. Her middle name “Quick-to-See” was not a reference to her eyesight but was given by her Shoshone grandmother as a sign of her ability to grasp things readily. From an early age Smith wanted to be an artist; as a child, she had herself photographed while dressed as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Though her father was not literate, education was important to Smith.

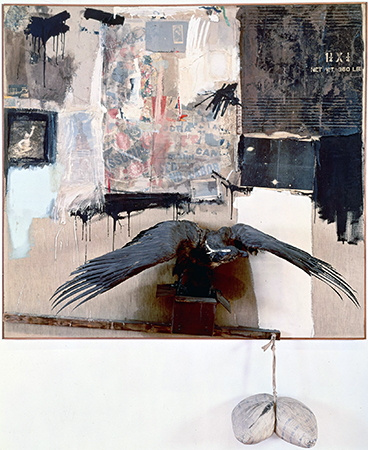

She received a bachelor of arts from Framingham State College in Massachusetts in 1976 in art education rather than in studio art because her instructors told her that no woman could have a career as an artist, though they acknowledged that she was more skilled than the men in her class. In 1980 she received a master of fine arts from the University of New Mexico. She was inspired by both Native and non-Native sources, including petroglyphs, Plains leger art, Diné saddle blankets, early Charles Russell prints of western landscapes, and paintings by twentieth-century artists such as Paul Klee, Joan Miró, Willem DeKooning, Jasper Johns, and especially Kurt Schwitters and Robert Rauschenberg (see image below). Both Schwitters and Rauschenberg brought objects from the quotidian world into their work, such as tickets, cigarette wrappers, and string.

In addition to her work as an artist, Smith has curated over thirty exhibitions to promote and highlight the art of other Native artists. She has also lectured extensively, been an artist-in-residence at numerous universities, and has taught art at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico the only four-year university dedicated to teaching Native youth across North America. In her years as an artist, Smith has received many honors, including an Eitelijorg Fellowship in 2007, a grant from the Joan Mitchell Foundation to create a comprehensive archive of her work, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Women’s Caucus for the Arts, the College Art Association’s Committee on Women in the Arts award, the 2005 New Mexico Governor’s award for excellence in the arts, as well as four honorary doctorate degrees.

Smith’s art shares her view of the world, offering her personal perspective as an artist, a Native American, and a woman. Her work creates a dialogue between the art and its viewers and explores issues of Native identity as it is seen by both Native Americans and non-Natives. Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People) restates the standard narratives of the history of the United States, specifically the desire to expand beyond “sea to shining sea,” as encompassed in the ideology of Manifest Destiny (the belief in the destiny of Western expansion), and raises the issue of contemporary inequities that are rooted in colonial experience.

1. Arlene Hirschfelder, Artists and Craftspeople, American Indian Lives, New York: Facts On File, 1994, page 115.

Additional resources:

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

“Smith, Jaune Quick-to-See” in American Indian History Online

Lawrence Abbot, I Stand in the Center of the Good: Interviews with Contemporary Native American Artists, University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1994.

Carolyn Kastner, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: An American Modernist, University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, 2013.

Melanie Herzog, “Building Bridges Across Canada: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.” School Arts (October 1992): 31–34.

Tricia Hurst, “Crossing Bridges: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Helen Hardin, Jean Bales.” Southwest Art, April 1981, 82–91.

Tricia Hurst, ”Jaune Quick-to-See Smith,” January 17–March 14, 1993. Norfolk, Virginia: Chrysler Museum, 1993.

Joni L. Murphy, “Beyond Sweetgrass: The Life and Art of Jaune Quick-To-See Smith.” Ph.D. dissertation. University of Kansas, 2008.

Michel Tuffery, Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beef 2000)

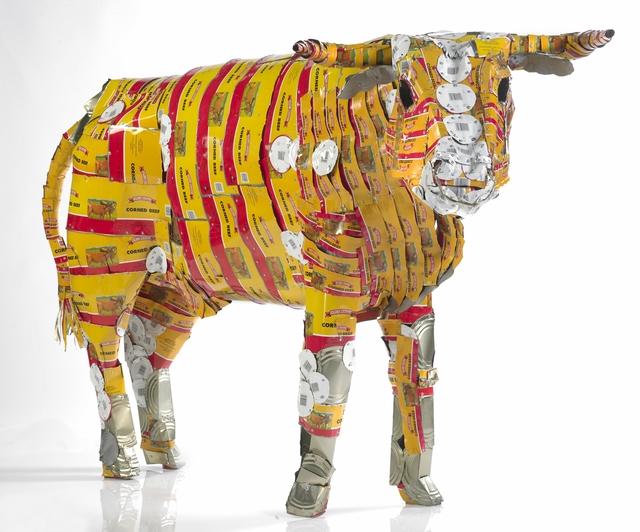

What can a tin can bull teach us about ecological and population health issues in the Pacific? Michel Tuffery is one of New Zealand’s best-known artists of Pacific descent, with links to Samoa, Rarotonga and Tahiti. He majored in printmaking at Dunedin’s School of Fine Arts, and describes art quite literally as his first language because he didn’t read, write or speak until he was 6 years old. Encouraged instead to express himself through drawing, he now aims artworks like Pisupo Lua Afe primarily at children, hoping to engage their curiosity and inspire them to care for both their own health and that of the environment.

Pisupo Lua Afe is one of Tuffery’s most iconic works, made from hundreds of flattened corned beef tins, riveted together to form a series of life-sized bulls. Despite evident connections to Pop Art, especially Andy Warhol’s celebrations of the humble Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962), it’s impossible to read this work solely in the terms of Western art history. So what is Tuffery trying to tell us?

Pisupo—canned food in the Pacific

Pisupo is the Samoan language version of “pea soup,” which was the first canned food introduced into the Pacific Islands. Pisupo is now a generic term used to describe the many types of canned food that are eaten in the Islands—including corned beef. Not only is corned beef a favorite food source in the Islands, it has also become a ubiquitous part of the ceremonial gift economy. At weddings and birthdays, and other important life events both in the Islands and in Islander communities in New Zealand, gifts of treasured textiles like fine mats and decorated barkcloths are made alongside food items and cash money. But unlike the Island feast foods gifted at these events—such as pigs and large quantities of root vegetables—canned corned beef is a processed food high in saturated fat, salt and cholesterol (a type of fat that clogs arteries). These are all things that contribute to disproportionately high incidences of diabetes and heart disease in Pacific Island populations as diets formerly high in locally grown fruits and vegetables, seafood, coconut milk and flesh, give way to cheap, imported foodstuffs.

So Tuffery’s sculpture is impossible to separate from the ceremonies at which brightly colored tins of corned beef now figure in large quantities. But these links to traditional economic exchanges and population health only tell part of the story. Pisupo Lua Afe also critiques serious issues of ecological health and food sovereignty. Tuffery is interested in the introduction of cattle to New Zealand and the Pacific Islands and how they impact negatively on the plants, landscapes and waterways of these countries, as well as how industrialized approaches to farming disrupt traditional food production.

Look at Pisupo Lua Afe. It’s literally a “tinned bull”—solid, hard-edged and weighty. Whereas a real cow has a visual softness suggested by its movements, eyes and coat, Tuffery’s tin cans and rivets—overlapping like large metal scales— better convey the capacity of beef and dairy cattle to destroy fragile island eco-systems. Look closer—single out just one flattened can. Think about all the cans that were emptied to make Pisupo Lua Afe. Then think about all the cans that are emptied and discarded in the Pacific Islands each year. Tuffery is gesturing rather obviously towards the challenge of rubbish disposal in Island economies where creative “upcycling” of materials into new objects is often more common than the civic recycling regimes of larger cities and countries (upcycling refers to reusing discarded objects to create a product of a higher value). What use is there for thousands of empty tin cans? And what use are foods that cause ill health, damage the environment, and take up large swathes of land formerly used to grow healthier, indigenous foods? Especially when the Pacific Island nations under Tuffery’s scrutiny are recipients of some of the worst products of such agricultural farming: fatty lamb flaps and turkey tails, and tinned corned beef.

Food sovereignty

Food sovereignty (sometimes called food security) is a great lens through which to view the various threads of traditional economic exchanges, population health, environmental degradation and industrialized food production introduced so far. Food sovereignty is the right of a nation and its peoples to decide who controls how, where and by whom their food is to be produced, and what that food will be. For Indigenous peoples in the Pacific, food and the environment are sacred gifts. There cannot be food sovereignty without control over food production and ownership, and without appropriate care of the environment.

Alongside Pisupo Lua Afe and his other tin can bulls, Tuffery has produced many artworks that address challenges to food sovereignty and the continued exploitation of Pacific Island resources, including the taro leaf blight epidemic in Samoa in 1993, and drift net fishing that is depleting fish stocks. For example, he’s made fish tin sculptures, like his “tinned bull,” which upcycle cans that hold another “staple” food in the Pacific: tinned mackerel. Tuffery made two of these for an exhibition called Le Folauga, shown in Auckland, New Zealand in 2007, which are now in the collection of the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

In the exhibition’s catalogue he explained:

O le Saosao Lapo’a and Asiasi I reflect on the ironic and irreversible impact that over-fishing and exploitation of the Pacific’s natural resources has wrought on the traditional Pacific lifestyle. This includes changing virtually overnight the dietary habits of generations.

Is it co-incidental that significantly increasing health and dietary problems amongst Pacific Islanders has occurred during the same period that their premium fisheries catches are exported? And at the same time locals have experienced explosive growth of canned & other imported products flooding into the Pacific?

Tuffery states the aims of his works very clearly. His fish tin sculptures are perhaps even more interesting and evocative because they are also functional fish-smokers used to cure and preserve fish. They have been used in this way at his exhibition openings, bringing a smoky, wood- and fish-scented haze to the gallery experience.

Firebreathing bulls?

Tuffery has also brought his “tinned beef” bulls to smoky life in various performative installations throughout the world, by installing fireworks inside their heads to give them the appearance of breathing fire. Mounted on castors with their necks articulated so their heads can be turned, he has staged bullfights with his fire breathing monsters, accompanied by drummers and groups of human performers issuing fierce challenges. But these performances have not been restricted to the sanctuary of the white walled gallery—these were performed outdoors, on city streets, to reach a community that might not otherwise come into the gallery to encounter his work.

Additional resources:

This work at the Museum of New Zealand

Waking up the Objects—Michel Tuffery talks about his practice (video)

Tales from Te Papa: Pisupo Lua Afe Michel Tuffery’s fish tin sculptures (Le Folauga) (video)

Michel Tuffery and Patrice Kaikilekofe’s artist performance Povi tau vaga (The challenge) 1999

Issue-based Assemblage Sculpture: Pisupo lua afe (Corned Beef 2000), 1994 from the New Zealand Ministry of Education

Jennifer Hay, “Povi Christlike (Christchurch Bull) by Michael Tuffery”

More on Michael Tuffery from Tautai

Thiebaud, Ponds and Streams

by DR. LAUREN PALMOR, FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Can the commonplace working farmland of California’s Sacramento River Valley be a place of of breathtaking beauty?

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Wayne Thiebaud, Ponds and Streams, 2001, acrylic on canvas, 182.9 x 152.4 cm (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, ©Wayne Thiebaud), a Seeing America video

Jeff Wall, A View from an Apartment

Jeff Wall’s A View from an Apartment is a large photographic transparency displayed on an electric light-box. Characteristic of Wall’s work, this format offers sharp figures in rich saturated colors, made even more intense by the lights that illuminate the image from behind. At almost 5 ½’ x 8’, the photograph approaches human scale. It’s as though the viewer could simply walk into the scene—or that the women in the image might walk out.

At first glance, this appears to be an ordinary genre scene. The large scale and striking detail draw the viewer closer to examine the image—the modern decor, the half-finished laundry, a cluttered coffee table. One woman walks forward while folding a cloth napkin; another pauses at a magazine page that’s momentarily caught her eye. And, in the background, framed by the large picture window, is a panoramic view of Vancouver’s harbor just outside.

Photography as Painting

Wall was trained as a painter and art historian and became known in the 1970s alongside artists like Cindy Sherman and Sherrie Levine. Influenced by conceptual art practices, as well as the pervasiveness of film and the mass media, this generation of artists turned to photography as a way to challenge our expectations about images and their meaning, and our assumption that the camera never lies.

A View from an Apartment initially evokes the larger-than-life feel of a film or an advertising billboard; but, in many ways, Wall’s photograph has more in common with painting. Its monumental presentation and implicit narrative recall the academic tradition of history painting, where artists idealized their imagery in order to glorify individuals and important events of the past. Moreover, like a painter, Wall carefully composed the photograph to direct our gaze and frame key elements in the scene. The repeated diagonal lines of the television, the shelves above, and the basket below pull our eye to the standing woman. Her forward motion leads us to the sitting area, which, in turn, draws our attention up to the window and the view outside.

Wall’s work might also be compared to Realism of the 19th century. Like Édouard Manet, Wall depicts common scenes of modern life, thus elevating contemporary experience to the fine art status of the classical past. Realists like Manet challenged established artistic values by rejecting illusionistic painting techniques of the past. Wall issues a similar critique through his practice to deliberately stage his photographs. In A View from an Apartment, the artist gave his model a budget to furnish and live in the apartment, which he then photographed over several months. He used digital editing to combine multiple shots to achieve the final image. This creative process forces us to question the photograph’s value as an accurate record of the scene, and effectively demonstrates the artifice inherent to established traditions of art.

The Transparent Window

For all of Wall’s careful planning of the interior, the titular view of the harbor most distinguishes A View from an Apartment. Framed by the window, the harbor scene contrasts dramatically to the mundanity of life inside. This picture within a picture forces us to examine fundamental questions about art, its ability to represent the world around us, and our own relationship to those surroundings.

Illusionism in traditional art teaches that a painting is like a window on the world. The picture plane dissolves to reveal a distant expanse before us. But, in Wall’s work, the photographic image denies such illusionism by presenting an actual landscape, mechanically captured by the artist’s camera. It also heightens spatial ambiguity in the work. Here the photograph’s planar surface does not dissolve; rather the window is clearly real, evidenced by light reflected from lamps inside the apartment. The transparent window paradoxically calls attention to the solid apartment wall that separates the figures from the outside world, a barrier underscored by the women’s obliviousness to the vista the viewer enjoys while standing before the photograph.

Wall’s use of the apartment view to create a discourse on art’s illusionism finds a place within this important recurring theme in art history. Painters, from Diego Velasquez in the 17th century and Henri Matisse in the 20th century raised similar questions by revealing the distance between reality and their representations of the real. In the 1970s, photorealists like Richard Estes drew on photographic images to highlight the ambiguity and formal play found in representational painting. Wall contributes to this on-going tradition through his references to modern cinema, mass advertising, and the role of photography in popular culture. His work reminds us to think twice about the images we see everyday. In the age of Photoshop, Instagram, and digital proliferation, what is real, and what is not, seems always to be in play.

Stéphane Couturier, Fenetre, Eastlake Greens, San Diego

by ELIZABETH GERBER, LACMA and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Building the American dream in the California desert.

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Stéphane Couturier, Fenetre, Eastlake Greens, San Diego, edition 4/8, 2001, dye coupler print, 130.81 x 107.95 x 2.54 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, © Stéphane Couturier)

Nari Ward, We the People (black version)

by DR. MINDY BESAW, CRYSTAL BRIDGES MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Nari Ward, We the People (black version), 2015, shoelaces, 8 × 27 feet (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art), a Seeing America video