11.1: A beginner's guide

- Page ID

- 67095

Defining “Pre-Columbian” and “Mesoamerica”

What does “pre-Columbian” mean?

The original inhabitants of the Americas traveled across what is now known as the Bering Strait, a passage that connected the westernmost point of North America with the easternmost point of Asia. The Western hemisphere was disconnected from Asia at the end of the last Ice Age, around 10,000 B.C.E.

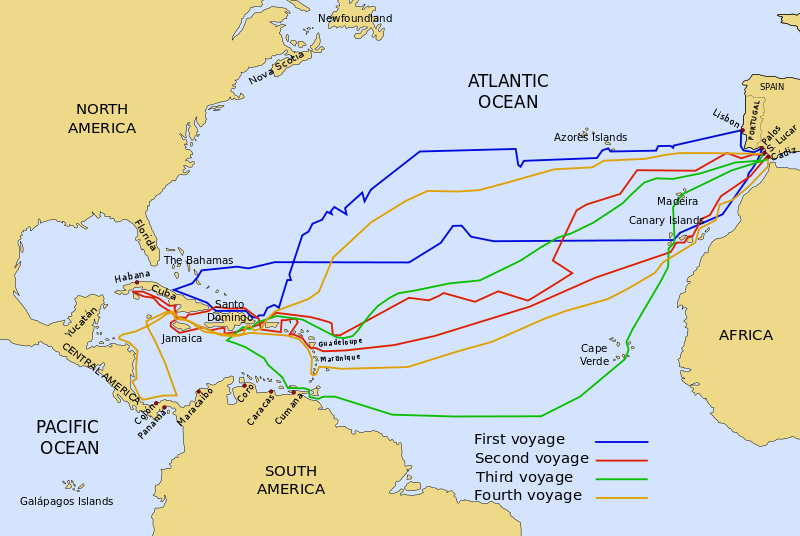

In 1492, the Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus arrived at the islands of Cuba and Hispaniola (today Haiti and the Dominican Republic), mistakenly thinking he had reached Asia. Columbus’ miscalculation marked the first step in the colonization of the Americas, or what was then seen as a “New World.” Incorrectly referring to the native inhabitants of Hispaniola as “Indians” (under the assumption that he had landed in India), Columbus established the first Spanish colony of the Americas. “Pre-Columbian” thus refers to the period in the Americas before the arrival of Columbus.

The Spanish conquistadores (conquerors) found that the “New World” was in fact not new at all, and that the indigenous people of Mesoamerica had established advanced civilizations with densely populated cities and towering architectural monuments such as at Teōtīhuacān, as well as advanced writing systems.

The term pre-Columbian is complicated however. For one thing, although it refers to the indigenous peoples of the Americas, the phrase does not directly reference any of the many sophisticated cultures that flourished in the Americas (think of the Aztec, Inka, or Maya, to name only a few) and instead invokes a European explorer. For this reason and because indigenous peoples flourished before and after the arrival of the Europeans, the term is often seen as flawed. Other terms such as pre-Hispanic, pre-Cortesian, or more simply, ancient Americas, are sometimes used.

What does “Mesoamerica” mean?

The region of Mesoamerica—which today includes central and south Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador—consists of a diverse geographic landscape of highlands, jungles, valleys, and coastlines. Mesoamericans did not exploit technological innovations such as the wheel—though they were used in toys— and did not develop metal tools or metalworking techniques until at least until 900 C.E. Instead, Mesoamerican artists are known for producing megalithic (large stone) sculpture and extremely sharp weapons from obsidian (volcanic glass). Featherwork and stonework in basalt, turquoise, and jade dominated Mesoamerican artistic production, while exceptional textiles and metallurgy flourished further south, among pre-Columbian Andean and Central American cultures, respectively.

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures shared certain characteristics such as the ritual ballgame,* pyramid building, human sacrifice, maize as an agricultural staple, and deities dedicated to natural forces (i.e. rain, storm, fire). Additionally, some Mesoamerican societies developed sophisticated systems of writing, as well as an advanced understanding of astronomy (which allowed for the development of accurate and complex calendar systems, including the 260-day sacred calendar and the 365-day agricultural calendar). As a result, cities like La Venta and Chichen Itza were aligned in relation to cardinal directions and had a sacred center. The fact that many of these cultural trademarks persisted for more than 2,000 years across civilizations as distinct as the Olmec (c. 1200–400 B.C.E.) and the Aztec (c. 1345 to 1521 C.E.), demonstrates the strong cultural bond of Mesoamerican cultures.

*The ballgame was played in different iterations at different times and in different places. It was played with a rubber ball that players hit with their elbows, hips, or knees. The ballgame was considered an important ritual in Mesoamerica and was practiced first by the Olmec and last by the Aztec. Since the rubber ball was solid and heavy, players wore protective gear to avoid injury and may have tried to score the ball through a ring, which was usually located high on the wall of the ballcourt. Numerous rubber balls and ballcourts have been discovered throughout Mesoamerica in El Tajín (image above) and Monte Albán, although the largest surviving ballcourt is located in Chichen Itza. While the ballgame was played by the elite, it was believed that the fate of the game and thus of the player was determined by the gods. As a result, the Mesoamerican ballgame held significant implications. Learn more about the ballgame here.

Google Street View of the Pyramid known as the Castillo, Chichen Itzá, Maya, Mexico, c. 800-900 C.E.

Introduction to the Spanish Viceroyalties in the Americas

“In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” These opening lines to a poem are frequently sung by schoolchildren across the United States to celebrate Columbus’s accidental landing on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola as he searched for passage to India. His voyage marked an important moment for both Europe and the Americas—expanding the known world on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and ushering in an era of major transformations in the cultures and lives of people across the globe.

When the Spanish Crown learned of the promise of wealth offered by vast continents that had been previously unknown to Europeans, they sent forces to colonize the land, convert the Indigenous populations, and extract resources from their newly claimed territory. These new Spanish territories officially became known as viceroyalties, or lands ruled by viceroys who were second to—and a stand-in for—the Spanish king.

The Viceroyalty of New Spain

Less than a decade after the Spanish conquistador (conqueror) Hernan Cortés and his men and Indigenous allies defeated the Mexica (Aztecs) at their capital city of Tenochtitlan in 1521, the first viceroyalty, New Spain, was officially created. Tenochtitlan was razed and then rebuilt as Mexico City, the capital of the viceroyalty. At its height, the viceroyalty of New Spain consisted of Mexico, much of Central America, parts of the West Indies, the southwestern and central United States, Florida, and the Philippines. The Manila Galleon trade connected the Philippines with Mexico, bringing goods such as folding screens, textiles, raw materials, and ceramics from around Asia to the American continent. Goods also flowed between the viceroyalty and Spain. Colonial Mexico’s cosmopolitanism was directly related to its central position within this network of goods and resources, as well as its multiethnic population. A biombo, or folding screen, in the Brooklyn Museum attests to this global network, with influences from Japanese screens, Mesoamerican shell-working traditions, and European prints and tapestries. Mexican independence from Spain was won in 1821.

The Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru was founded after Francisco Pizarro’s defeat of the Inka in 1534. Inspired by Cortés’s journey and conquest of Mexico, Pizarro had made his way south and inland, spurred on by the possibility of finding gold and other riches. Internal conflicts were destabilizing the Inka empire at the time, and these political rifts aided Pizarro in his overthrow. While the viceroyalty encompassed modern-day Peru, it also included much of the rest of South America (though the Portuguese gained control of what is today Brazil). Rather than build atop the Inka capital city of Cusco, the Spaniards decided to create a new capital city for Peru: Lima, which still serves as the country’s capital today.

In the eighteenth century, a burgeoning population, among other factors, led the Spanish to split the viceroyalty of Peru apart so that it could be governed more effectively. This move resulted in two new viceroyalties: New Granada and Río de la Plata. As in New Spain, independence movements here began in the early nineteenth century, with Peru achieving sovereignty in 1820.

Evangelization in the Spanish Americas

Soon after the military and political conquests of the Mexica (Aztecs) and Inka, European missionaries began arriving in the Americas to begin the spiritual conquests of Indigenous peoples. In New Spain, the order of the Franciscans landed first (in 1523 and 1524), establishing centers for conversion and schools for Indigenous youths in the areas surrounding Mexico City. They were followed by the Dominicans and Augustinians, and by the Jesuits later in the sixteenth century. In Peru, the Dominicans and Jesuits arrived early on during evangelization.

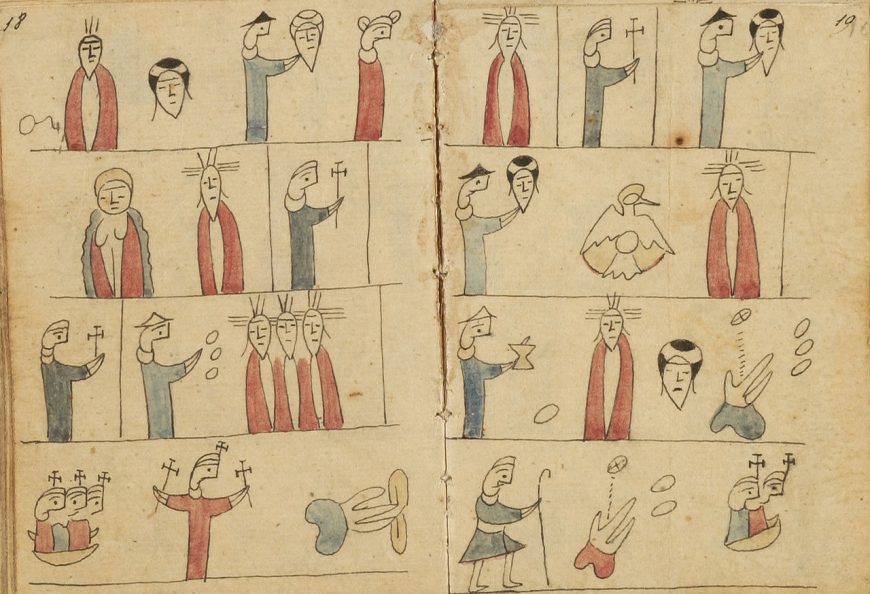

The spread of Christianity stimulated a massive religious building campaign across the Spanish Americas. One important type of religious structure was the convento. Conventos were large complexes that typically included living quarters for friars, a large open-air atrium where mass conversions took place, and a single-nave church. In this early period, the lack of a shared language often hindered communication between the clergy and the people, so artworks played a crucial role in getting the message out to potential converts. Certain images and objects (including portable altars, atrial crosses, frescoes, illustrated catechisms or religious instruction books, prayer books, and processional sculpture) were crafted specifically to teach new, Indigenous Christians about Biblical narratives.

This explosion of visual material created a need for artists. In the sixteenth century, the vast majority of artists and laborers were Indigenous, though we often do not have the specific names of those who created these works. At some of the conventos, missionaries established schools to train Indigenous boys in European artistic conventions. One of the most famous schools was at the convento of Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco in Mexico City, where the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, in collaboration with Indigenous artists, created the encyclopedic text known today as the Florentine Codex.

Strategies of Dominance in the Early Colonial Period

Spanish churches were often built on top of Indigenous temples and shrines, sometimes re-using stones for the new structure. A well-known example is the Church of Santo Domingo in Cusco, built atop the Inka Qorikancha (or Golden Enclosure). You can still see walls of the Qorikancha below the church.

This practice of building on previous structures and reusing materials signaled Spanish dominance and power. It had already been a strategy used by Spaniards during the Reconquest, or reconquista, of the Iberian (Spanish) Peninsula from its previous Muslim rulers. In southern Spain, for instance, a church was built directly inside the Great Mosque of Córdoba during this period. The reconquista ended the same year Columbus landed in the Americas, and so it was on the minds of Spaniards as they lay claim to the lands, resources, and peoples there. Some sixteenth-century authors even referred to Mesoamerican religious structures as mosques, revealing the pervasiveness of the Eurocentric Reconquest attitude they brought with them.

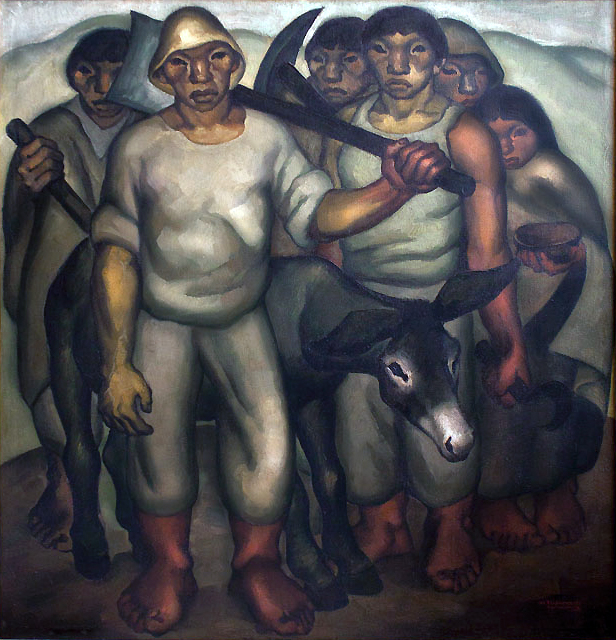

Throughout the sixteenth century, terrible epidemics and the cruel labor practices of the encomienda (Spanish forced labor) system resulted in mass casualties that devastated Indigenous populations throughout the Americas. Encomiendas established throughout these territories placed Indigenous peoples under the authority of Spaniards. While the goal of the system was to have Spanish lords educate and protect those entrusted to them, in reality it was closer to a form of enslavement. Millions of people died, and with these losses certain traditions were eradicated or significantly altered.

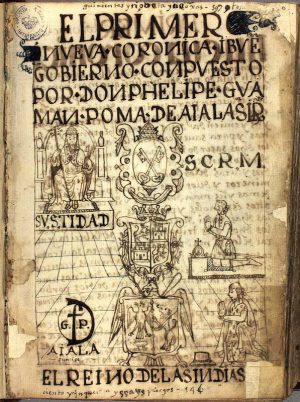

Nevertheless, this chaotic time period also witnessed an incredible flourishing of artistic and architectural production that demonstrates the seismic shifts and cultural negotiations that were underway in the Americas. Despite being reduced in number, many Indigenous peoples adapted and transformed European visual vocabularies to suit their own needs and to help them navigate the new social order. In New Spain and the Andes, we have many surviving documents, lienzos, and other illustrations that reveal how Indigenous groups attempted to reclaim lands taken from them or to record historical genealogies to demonstrate their own elite heritage. One famous example is a 1200-page letter to the king of Spain written by Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, an Indigenous Andean whose goal was to record the abuses the Indigenous population suffered at the hands of Spanish colonial administration. Guaman Poma also used the opportunity to highlight his own genealogy and claims to nobility.

Talking about Viceregal Art

How do we talk about viceregal art more specifically? What terms do we use to describe this complex time period and geographic region? Scholars have used a variety of labels to describe the art and architecture of the Spanish viceroyalties, some of which are problematic because they position European art as being superior or better and viceregal art as derivative and inferior.

Some common terms that you might see are “colonial,” “viceregal,” “hybrid,” or “tequitqui.” “Colonial” refers to the Spanish colonies, and is often used interchangeably with “viceregal.” However, some scholars prefer the term “colonial” because it highlights the process of colonization and occupation of the parts of the Americas by a foreign power. “Hybrid” and “tequitqui” are two of many terms that are used to describe artworks that display the mixing or juxtaposition of Indigenous and European styles, subjects, or motifs. Yet these terms are also inadequate to a degree because they assume that hybridity is always visible and that European and Indigenous styles are always “pure.”

Applying terms used to characterize early modern European art (Renaissance, Baroque, or Neoclassical, for instance) can be similarly problematic. A colonial Latin American church or a painting might display several styles, with the result looking different from anything we might see in Spain, Italy, or France. A Mexican featherwork, for example, might borrow its subject from a Flemish print and display shading and modeling consistent with classicizing Renaissance painting, but it is made entirely of feathers—how do we categorize such an artwork?

It is important that we not view Spanish colonial art as completely breaking with the traditions of the pre-Hispanic past, as unoriginal, or as lacking great artists. The essays and videos found here reveal the innovation, adaptation, and negotiation of traditions from around the globe, and speak to the dynamic nature of the Americas in the early modern period.

Additional resources:

Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520-1820

Spanish Colonial and 19th century art at LACMA

The Garrett Mesoamerican Manuscript Collection at Princeton University Library

Girolamo Ruscelli’s “Nveva Hispania tabvla nova” map in the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

The Florentine Codex at the World Digital Library

Juan Baptista Cuiris’s featherwork at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Latin American art: an introduction

Why is it important to study Latin American art today?

The study of Latin America and Latin American art is more relevant today than ever. In the United States, the burgeoning population of Latinos—people of Latin American descent—and consequently the rise of Spanish (and Spanglish) speakers, Latino musical genres, literature, and visual arts, require that we better understand the cultural origins of these diverse communities. Even beyond our borders, Latin American countries continue to exert influence over political and economic policies, while their artistic traditions are everyday made more and more accessible at cultural institutions like art museums, which regularly exhibit the work of Latin American artists. In many ways, Latin American and Latino culture is an inescapable reality, thus it is up to us, for the benefits of appreciation and integration, to tackle the difficult question of what it means to be from Latin America.

For many of us Latin America is not an entirely foreign concept, in fact our knowledge of it is most likely defined by a particular country, food, music, or artist, and sadly, it is also sometimes clouded by cultural stereotypes. What many of us often overlook, is the diversity of what it means to be Latin American and Latino. Interestingly, Latin America is not as different from the United States as we tend to think, since we both share in the history of conquest and imperialism, albeit from different perspectives. Thus the study of Latin American art should not necessarily be thought of as a narrative that is entirely separate from that of the United States, but rather as one that is shared.

What do we mean by Latin America?

Latin America broadly refers to the countries in the Americas (including the Caribbean) whose national language is derived from Latin. These include countries where the languages of Spanish, Portuguese, and French are spoken. Latin America is therefore a historical term rooted in the colonial era, when these languages were introduced to the area by their respective European colonizers. The term itself, however, was not coined until the nineteenth century, when Argentinean jurist Carlos Calvo and French engineer Michel Chevalier, in reference to the Napoleonic invasion of Mexico in 1862, used the term “Latin” to denote difference from the “Anglo-Saxon” people of North America. It gained currency during the twentieth century when Mesoamerican, Central American, Caribbean, and South American countries sought to culturally distance themselves from North America, and more specifically from the United States.

Today, Latin America is considered by many scholars to be an imprecise and highly problematic term, since it prescribes a collective entity to a conglomerate of countries that remain vastly different. In the case of countries that share the same language their cultural bond is much stronger, since despite their potentially different pre-conquest origins, they continue to share collective colonial histories and contemporary postcolonial predicaments. Spanish-speaking countries are therefore known as Spanish America or Hispanoamérica, while those that were colonized by the Iberian countries of Spain and Portugal, fall under the broader category of Iberoamérica, thus including Brazil. In addition to these Latin-derived languages, indigenous tongues like Quechua, spoken by more than 8 million people in South America, are still preserved today. When discussing countries such as the French-speaking Haiti and Spanish-speaking Mexico, the similarities become much harder to articulate.

That said, the collective experiences of the conquest, slavery, and imperialism—and even today, those of underdevelopment, environmental degradation, poverty, and inequality—prove to be an undeniable unifying force, and as the artworks of these countries demonstrate, the idea of both a collective and local experience exists among the selected countries. For the purposes of clarity, the term Latin America is used loosely, whether referring to the pre- or post-conquest era. At the same time however, this term will be challenged in order to demonstrate both the limitations and benefits of thinking of Latin American art as a shared artistic tradition.

It is anachronistic to discuss a Latin American artistic tradition before independence, and as a result pre-Columbian and colonial art are discussed according to specific regions. However, it is best to approach the art of the 19th and 20th centuries as a whole, in large part due to the emergence of Latin Americanism and Pan-Americanism (a twentieth-century movement that rallied all American countries around a shared political, economic, and social agenda). Contemporary artists working in a globalized art world and often times outside of their country of origin give new meaning to what it means to not necessarily be a Latin American artist, but rather a global one.

Geography

While the countries of Latin America can be categorized by language, they can also be organized by region. Before 1492 C.E., the regions of Mesoamerica, the Isthmus (or Intermediate) Area, the Caribbean, and the Andes shared certain cultural traits, such as the same calendars, languages, and sports, as well as comparable artistic and architectural traditions. After colonization, however, the borders shifted somewhat with the creation of the viceroyalties of New Spain, Peru, New Granada, La Plata, and Brazil. After independence (and still today), the countries stretching from Mexico to Honduras form part of the region of Mesoamerica (also known as Middle America since the Greek word “meso” means “middle”). Parts of Honduras and El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama, which lie to the south of Middle America, make up Central America, while all the countries to the south of Panama form part of South America. The Caribbean is sometimes considered part of Central America or at times entirely excluded. The United States also factors into this discussion of Latin American art—through the work of Latino, Chicano, and Nuyorican artists.

Lastly, it is important to note that when discussing specific Latin American countries, the geographical scope in question will correspond to the current, rather than former borders. While these linguistic and geographical parameters lend clarity to the study of Latin American art, they often obscure cultural differences that are not border specific. The coastal cultures of Colombia and Venezuela for instance, are closer to those of the Caribbean than to their mainland counterparts. This is reflected not only in the similar climate, diet, and customs of these particular areas, but also in their artistic production. The islands of the Caribbean, however, are also a geographical region (delineated by the Caribbean Sea), thus the distinction between regions depends on how and where you draw the borders—reminding us of the flexibility and variety of labels that can be employed to describe the same region.

A similar distinction occurs in South America, where cultures vary greatly not necessarily across countries, but rather according to geographical landmarks, the two most prominent of which are the Andes Mountains and the Amazon Rainforest. Stretching from Chile to Venezuela, the Andes traverse the western portion of South America. At impressive heights and in snow-covered peaks, the Andean cultures of South America share irrigation techniques, textile traditions, and native languages, such as Quechua, the former language of the Incas that is today spoken by millions, that continue to this day. The Amazon, the world’s largest tropical rainforest, is contained mostly in Brazil, although it stretches into the bordering countries of Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana. Just these two landmarks, without mentioning the Pacific and Atlantic coastal cultures of South America, reveal the geographical, and thus cultural diversity of the area.Latin America is a useful, but by no means perfect term to describe a vast expanse of land that is historically, culturally, and geographically diverse.

From networks of exchange to a global trade network

From as early as the pre-Columbian era, there existed networks of exchange among the early civilizations of Latin America, through trade networks that stretched from Mesoamerica to South America. Limited by technology and transportation, forms of indigenous contact were mainly restricted to the American continent. With the arrival of European conquistadores (Spanish for “conquerors”), the panorama changed entirely. Starting in the sixteenth century, and now exposed to Africa, through the Atlantic Slave Trade, and Asia, through the trade network of the Manila Galleon, Latin America entered into an era of global contact that continues to this day.

With the nineteenth-century struggles for independence, collaborations across countries increased, not to mention alliances were formed, that although unsuccessful, nevertheless tried to articulate the idea of a collective Latin American entity. During the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, namely as a result of socio-political transformations, migration, exile, and diaspora (the dispersion of people from their homeland), travel became a trademark of modern art, further contributing to the internationalism of Latin American art. As a result of these networks of exchange, which began before colonization and continue to this day, Latin American art is difficult to categorize. It is in fact hybrid and pluralistic, the product of multi-cultural conditions.

“Non-Western” art?

It is critical to also consider the negative impact of the artificial insertion of Latin American art into Western and non-Western narratives. While the term “Western art” refers largely to Europe and North America, whose artistic tradition looks back to the Classicism of the ancient Greeks and Romans, the term “non-Western art” includes everything else. This distinction has plagued Latin American art, since—except for pre-Columbian art—it mostly fits in the category of Western art history. This categorization however, is debatable, with some scholars positing that Latin American art is a non-Western artistic tradition that owes more to its pre-Columbian roots, than to its European influences. Often, when Latin American art is discussed in a Western context, it is usually presented as derivative of European or North American art, or simply treated as the “other,” meaning different from the artistic mainstream.

This notion can be countered by exposing the many ways that artists adopted, rather than imitated, these outside influences, and by demonstrating the manner through which these forms of exchange were reciprocal—rather than unilateral—as is usually discussed. A case in point can be seen in the work of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo (right), who are usually included in textbooks on either Western or Modern art, but whose presence is marginalized in comparison to their European and North American counterparts.

A survey of non-Western art would surely include indigenous Latin American art, but it might not include any artworks from the sixteenth century (conquest) onwards. As a result—and depending on the context in which you study Latin American art—one can end up with an entirely different and fragmented view of its artistic tradition. This is even made more complicated when considering the artistic selections in the pre-Columbian and Colonial sections versus those in the Modern sections, as evidenced by the number of ritual objects (considered artworks as a result of their aesthetic qualities and craftsmanship). Only from the broader perspective of Latin American art can individual artistic traditions be better appreciated. The plurality of meaning and the inability to neatly title or categorize Latin American art is precisely what makes this area of study so unique, and therefore interesting. A living and constantly evolving field of study, Latin American art will continue to surprise you with its multifaceted and multilayered history.

About geography and chronological periods in Native American art

Typically when people discuss Native American art they are referring to peoples in what is today the United States and Canada. You might sometimes see this referred to as Native North American art, even though Mexico, the Caribbean, and those countries in Central America are typically not included. These areas are commonly included in the arts of Mesoamerica (or Middle America), even though these countries are technically part of North America.

So how do we consider so many groups and of such diverse natures? We tend to treat them geographically: Eastern Woodlands (sometime divided between North and Southeast), Southwest and West (or California), Plains and Great Basin, and Northwest Coast and North (Sub-Arctic and Arctic). While this is by no means a perfect way of addressing the varied tribes and First Nations within these areas, such a map can help to reveal patterns and similarities.

Chronology

Chronology (the arrangement of events into specific time periods in order of occurrence) is tricky when discussing Native American or First Nations art. Each geographic region is assigned different names to mark time, which can be confusing to anyone learning about the images, objects, and architecture of these areas for the first time. For instance, for the ancient Eastern Woodlands, you might read about the Late Archaic (c. 3000–1000 B.C.E.), Woodland (c. 1100 BCE–1000 C.E.), Mississippian (c. 900–c. 1500/1600 C.E.), and Fort Ancient (c. 1000–1700) periods. But if we turn to the Southwest, there are alternative terms like Basketmaker (c. 100 B.C.E.–700 C.E.) and Pueblo (700–1400 C.E.). You might also see terms like pre- and post-Contact (before and after contact with Europeans and Euro-Americans) and Reservation Era (late nineteenth century) that are used to separate different moments in time. Some of these terms speak to the colonial legacy of Native peoples because they separate time based on interactions with foreigners. Other terms like Prehistory have fallen out of favor and are problematic since they suggest that Native peoples didn’t have a history prior to European contact.

Organization

We arrange Native American and First Nations material prior to circa 1600 in “North America: later cultures before European colonization”, which includes material about the Ancestral Puebloans, Moundbuilders, and Mississippian peoples. Those objects and buildings created after 1600 are in their own section, which will hopefully highlight the continuing diversity of Native groups as well as the transformations (sometimes violent ones) occurring throughout parts of North America. Artists working after 1914 (or the beginning of WWI) are not located in the Art of the Americas section, but rather in the modern and contemporary areas.

Additional resources:

Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, Native North American Art, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

Brian M. Fagan, Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent, 4th ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005).

David W. Penney, North American Indian Art ( New York: Thames and Hudson, 2004).

Karen Kramer Russell, ed., Shapeshifting: Transformations in Native American Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

Terms and Issues in Native American Art

Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, the Dakotas, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah, Wisconsin, Wyoming—all state names derived from Native American sources. Pontiac, moose, raccoon, pecan, kayak, squash, chipmunk, Winnebago. These common words also derive from different Native words and demonstrate the influence these groups have had on the United States.

Pontiac, for instance, was an 18th century Ottawa chief (also called Obwandiyag), who fought against the British in the Great Lakes region. The word “moose,” first used in English in the early seventeenth century during colonization, comes from Algonquian languages.

Stereotypes

Stereotypes persist when discussing Native American arts and cultures, and sadly many people remain unaware of the complicated and fascinating histories of Native peoples and their art. Too many people still imagine a warrior or chief on horseback wearing a feathered headdress, or a beautiful young “princess” in an animal hide dress (what we now call the Indian Princess). Popular culture and movies perpetuate these images, and homogenize the incredible diversity of Native groups across North America. There are too many different languages, cultural traditions, cosmologies, and ritual practices to adequately make broad statements about the cultures and arts of the indigenous peoples of what is now the United States and Canada.

In the past, the term “primitive” has been used to describe the art of Native tribes and First Nations. This term is deeply problematic—and reveals the distorted lens of colonialism through which these groups have been seen and misunderstood. After contact, Europeans and Euro-Americans often conceived of the Amerindian peoples of North America as noble savages (a primitive, uncivilized, and romanticized “Other”). This legacy has affected the reception and appreciation of Native arts, which is why much of it was initially collected by anthropological (rather than art) museums. Many people viewed Native objects as curiosities or as specimens of “dying” cultures—which in part explains why many objects were stolen or otherwise acquired without approval of Native peoples. Many sacred objects, for example, were removed and put on display for non-Native audiences. While much has changed, this legacy lives on, and it is important to be aware of and overcome the many stereotypes and biases that persist from prior centuries.

Repatriation

One significant step that has been taken to correct some of this colonial legacy has been NAGPRA, or the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1992. This is a U.S. federal law that dictates that “human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony, referred to collectively in the statute as cultural items” be returned to tribes if they can demonstrate “lineal descent or cultural affiliation.” Many museums in the U.S. have been actively trying to repatriate items and human remains. For example, in 2011, a museum returned a wooden box drum, a hide robe, wooden masks, a headdress, a rattle, and a pipe to the Tlingít T’akdeintaan Clan of Hoonah, Alaska. These objects were purchased in 1924 for $500.

In the 19th century, many groups were violently forced from their ancestral homelands onto reservations. This is an important factor to remember when reading the essays and watching the videos in this section because the art changes—sometimes very dramatically—in response to these upheavals. You might read elsewhere that objects created after these transformations are somehow less authentic because of the influence of European or Euro-American materials and subjects on Native art. However, it is crucial that we do not view those artworks as somehow less culturally valuable simply because Native men and women responded to new and sometimes radically changed circumstances.

Many twentieth and twenty-first century artists, including Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Sioux), Alex Janvier (Chipewyan [Dene]) and Robert Davidson (Haida), don’t consider themselves to work outside of so-called “traditional arts.” In 1958, Howe even wrote a famous letter commenting on his methods when his work was denounced by Philbrook Indian Art Annual Jurors as not being “authentic” Native art:

Who ever said that my paintings are not in the traditional Indian style has poor knowledge of Indian art indeed. There is much more to Indian Art than pretty, stylized pictures. There was also power and strength and individualism (emotional and intellectual insight) in the old Indian paintings. Every bit in my paintings is a true, studied fact of Indian paintings. Are we to be held back forever with one phase of Indian painting, with no right for individualism, dictated to as the Indian has always been, put on reservations and treated like a child, and only the White Man knows what is best for him? Now, even in Art, ‘You little child do what we think is best for you, nothing different.” Well, I am not going to stand for it. Indian Art can compete with any Art in the world, but not as a suppressed Art…. 1

More terms and issues

The word Indian is considered offensive to many peoples. The term derives from the Indies, and was coined after Christopher Columbus bumped into the Caribbean islands in 1492, believing, mistakenly, that he had found India. Other terms are equally problematic or generic. You might encounter many different terms to describe the peoples in North America, such as Native American, American Indian, Amerindian, Aboriginal, Native, Indigenous, First Nations, and First Peoples.

Native American is used here because people are most familiar with this term, yet we must be aware of the problems it raises. The term applies to peoples throughout the Americas, and the Native peoples of North America, from Panama to Alaska and northern Canada, are incredibly diverse. It is therefore important to represent individual cultures as much as we possibly can. The essays here use specific tribal and First Nations names so as not to homogenize or lump peoples together. On Smarthistory, the artworks listed under Native American Art are only those from the United States and Canada, while those in Mexico and Central America are located in other sections.

You might also encounter words like tribes, clans, or bands in relation to the social groups of different Native communities. The United States government refers to an Indigenous group as a “tribe,” while the Canadian government uses the term “ban.” Many communities in Canada prefer the term “nation.”

Identity

In order to be legally classified as an indigenous person in the United States and Canada, an individual must be officially listed as belonging to a specific tribe or band. This issue of identity is obviously a sensitive one, and serves as a reminder of the continuing impact of colonial policy. Many contemporary artists, including James Luna (Pooyukitchum/Luiseño) and Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith (from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Indian Nation), address the problem of who gets to decide who or what an Indian is in their work.

Luna’s Artifact Piece (1987) and Take a Picture with a Real Indian (1993) both confront issues of identity and stereotypes of Native peoples. In Artifact Piece, Luna placed himself into a glass vitrine (like the ones we often see in museums) as if he were a static artifact, a relic of the past, accompanied by personal items like pictures of his family. In Take a Picture with a Real Indian, Luna asks his audience to come take a picture with him. He changes clothes three times. He wears a loincloth, then a loincloth with a feather and a bone breastplate, and then what we might call “street clothes.” Most people choose to take a picture with him in the former two, and so Luna draws attention to the problematic idea that somehow he is less authentically Native when dressed in jeans and a t-shirt.

Even the naming conventions applied to peoples need to be revisited. In the past, the Navajo term “Anasazi” was used to name the ancestors of modern-day Puebloans. Today, “Ancestral Puebloans” is considered more acceptable. Likewise, “Eskimo” designated peoples in the Arctic region, but this word has fallen out of favor because it homogenizes the First Nations in this area. In general, it is always preferable to use a tribe or Nation’s specific name when possible, and to do so in its own language.

Additional resources:

Interview with James Luna for the Smithsonian

The National Museum of the American Indian

Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, Native North American Art, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

Brian M. Fagan, Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent, 4th ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005).

David W. Penney, North American Indian Art (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2004).

Karen Kramer Russell, ed., Shapeshifting: Transformations in Native American Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).