10.5: Cubism + early abstraction (II)

- Page ID

- 65581

Futurism

This group of young and rebellious Italian writers and artists was determined to celebrate industrialization.

1909 - 1914

Italian Futurism: An Introduction

by EMILY CASDEN

Can you imagine being so enthusiastic about technology that you name your daughter Propeller? Today we take most technological advances for granted, but at the turn of the last century, innovations like electricity, x-rays, radio waves, automobiles and airplanes were extremely exciting. Italy lagged Britain, France, Germany, and the United States in the pace of its industrial development. Culturally speaking, the country’s artistic reputation was grounded in Ancient, Renaissance and Baroque art and culture. Simply put, Italy represented the past.

In the early 1900s, a group of young and rebellious Italian writers and artists emerged determined to celebrate industrialization. They were frustrated by Italy’s declining status and believed that the “Machine Age” would result in an entirely new world order and even a renewed consciousness.

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the ringleader of this group, called the movement Futurism. Its members sought to capture the idea of modernity, the sensations and aesthetics of speed, movement, and industrial development.

A manifesto

Marinetti launched Futurism in 1909 with the publication his “Futurist manifesto” on the front page of the French newspaper Le Figaro. The manifesto set a fiery tone. In it Marinetti lashed out against cultural tradition (passatismo, in Italian) and called for the destruction of museums, libraries, and feminism. Futurism quickly grew into an international movement and its participants issued additional manifestos for nearly every type of art: painting, sculpture, architecture, music, photography, cinema—even clothing.

The Futurist painters—Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Gino Severini, and Giacomo Balla—signed their first manifesto in 1910 (the last named his daughter Elica—Propeller!). Futurist painting had first looked to the color and the optical experiments of the late 19th century, but in the fall of 1911, Marinetti and the Futurist painters visited the Salon d’Automne in Paris and saw Cubism in person for the first time. Cubism had an immediate impact that can be seen in Boccioni’s Materia of 1912 for example. Nevertheless, the Futurists declared their work to be completely original.

Dynamism of Bodies in Motion

The Futurists were particularly excited by the works of late 19th-century scientist and photographer Étienne-Jules Marey, whose chronophotographic (time-based) studies depicted the mechanics of animal and human movement.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\)

A precursor to cinema, Marey’s innovative experiments with time-lapse photography were especially influential for Balla. In his painting Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, the artist playfully renders the dog’s (and dog walker’s) feet as continuous movements through space over time.

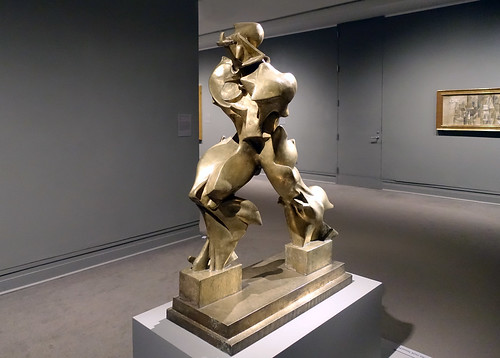

Entranced by the idea of the “dynamic,” the Futurists sought to represent an object’s sensations, rhythms and movements in their images, poems and manifestos. Such characteristics are beautifully expressed in Boccioni’s most iconic masterpiece, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (see above).

The choice of shiny bronze lends a mechanized quality to Boccioni’s sculpture, so here is the Futurists’ ideal combination of human and machine. The figure’s pose is at once graceful and forceful, and despite their adamant rejection of classical arts, it is also very similar to the Nike of Samothrace.

Politics & War

Futurism was one of the most politicized art movements of the twentieth century. It merged artistic and political agendas in order to propel change in Italy and across Europe. The Futurists would hold what they called serate futuriste, or Futurist evenings, where they would recite poems and display art, while also shouting politically charged rhetoric at the audience in the hope of inciting riot. They believed that agitation and destruction would end the status quo and allow for the regeneration of a stronger, energized Italy.

These positions led the Futurists to support the coming war, and like most of the group’s members, leading painter Boccioni enlisted in the army during World War I. He was trampled to death after falling from a horse during training. After the war, the members’ intense nationalism led to an alliance with Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party. Although Futurism continued to develop new areas of focus (aeropittura, for example) and attracted new members—the so-called “second generation” of Futurist artists—the movement’s strong ties to Fascism has complicated the study of this historically significant art.

Additional resources:

Unique Forms in the Continuity of Space at MoMA

The Futurist Manifestos and related materials

Charles Bernstein reading the Futurist Manifesto at MoMA (video)

Boccioni’s Materia in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

Étienne-Jules Marey at MoMA

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Futurist Free Word Painting

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

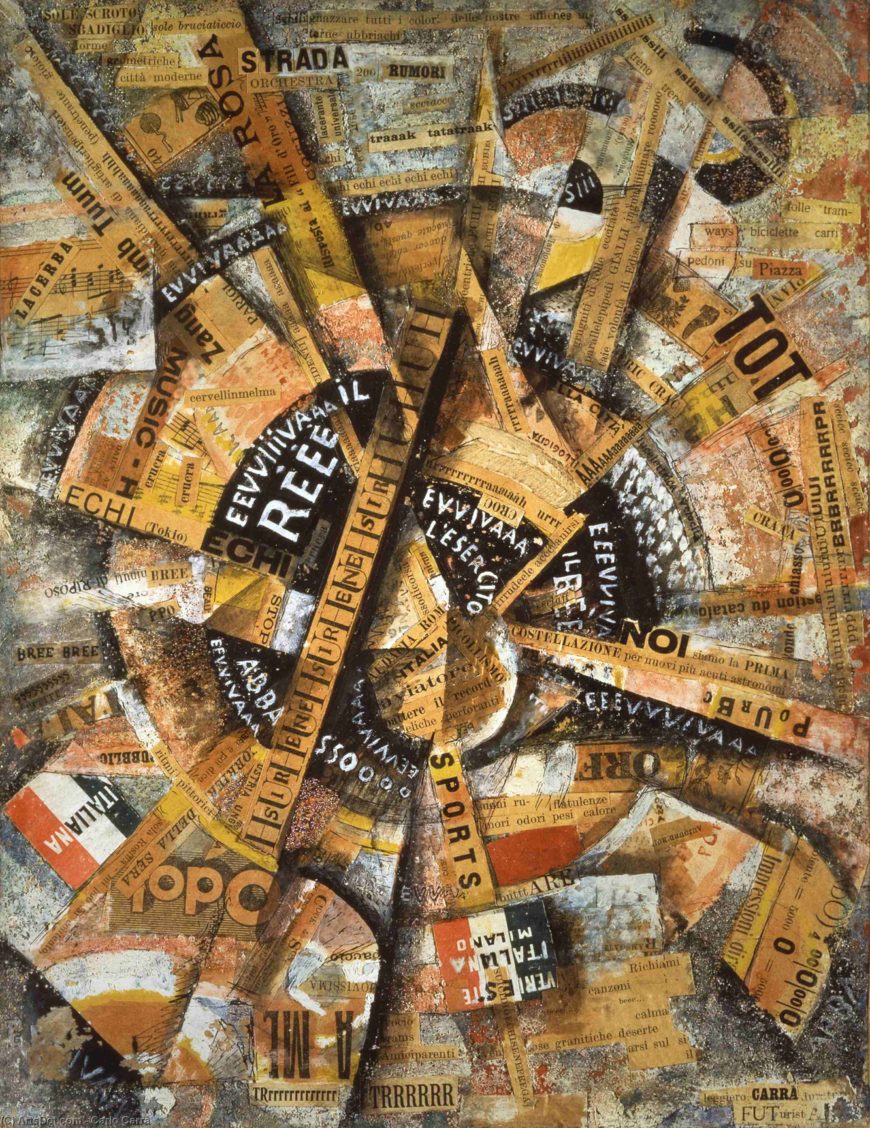

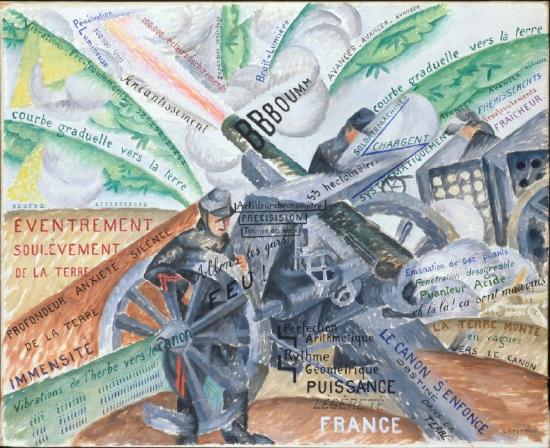

Created in the politically volatile days leading up to World War I, Carlo Carrà’s Interventionist Demonstration (Patriotic Holiday – Free Word Painting) displays both the Italian Futurists’ avant-garde techniques and their militant nationalism. It is a collage painting that uses words as its primary element.

The composition rotates like an airplane propeller, and the word “aviator” is pasted at its heart. Dozens of pasted and painted words fan out from the center like voices shouting in a crowd. There are clippings from advertisements, Futurist poems, and newspaper articles, as well as two painted Italian flags and graffiti-like inscriptions of popular slogans supporting the Italian army and king, and condemning Austria.

Instructions from a propeller

Free word painting is a development of Filippo Marinetti’s parole in libertà — “words in freedom,” often translated as “free word poetry.” Inspired by the intensity of his experiences as a war correspondent in Libya, Marinetti first described parole in libertà as instructions emanating from an airplane propeller. The instructions included the abolition of syntax, punctuation, conjunctions, adverbs, and adjectives. Verbs must be used only in the infinitive form.

These restrictions defined a poetry largely based on conjunctions of nouns intended to directly express things and their physical qualities. For example, a section of Marinetti’s first free word poem Battle of Weight + Smell reads, “20 meters battalions-ants cavalry-spiders roads-fords general-island couriers-locusts sands-revolution howitzers-grandstands clouds-grates guns-martyrs . . .”\(^{[1]}\)

A multi-sensory approach

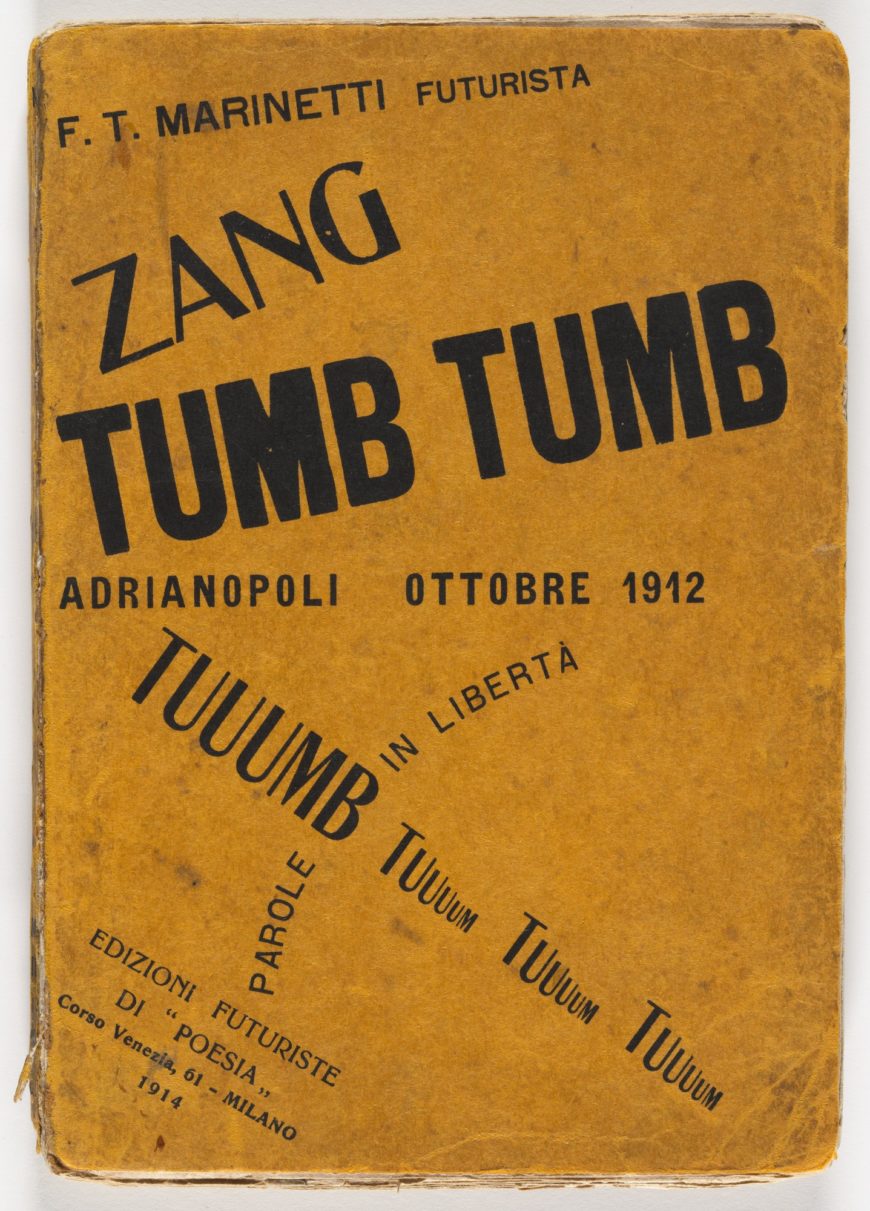

The Futurists developed multi-sensory approaches to communicate the experiences of physical reality. Instead of description, Futurist poets used onomatopoeia to convey sounds directly. The title of Marinetti’s poem ZANG TUMB TUUUM is onomatopoeic; the “words” are the successive sounds of an artillery shell firing, exploding, and reverberating.

In addition to sound, parole in libertà appealed directly to vision and instigated a revolution in typography. The cover of ZANG TUMB TUUUM uses different weights of type to signify the relative volume of different sounds and layout to convey relationships and physical movement. ZANG is on top and angles steeply upward to indicate the firing of the shell. The twice-repeated TUMB is lower and heavier to convey the booming impact of the shell and the power of the explosion. The diminishing echoes of the sonic reverberation are represented below by the steep down-sloping TUUUMBs that shrink with each repetition.

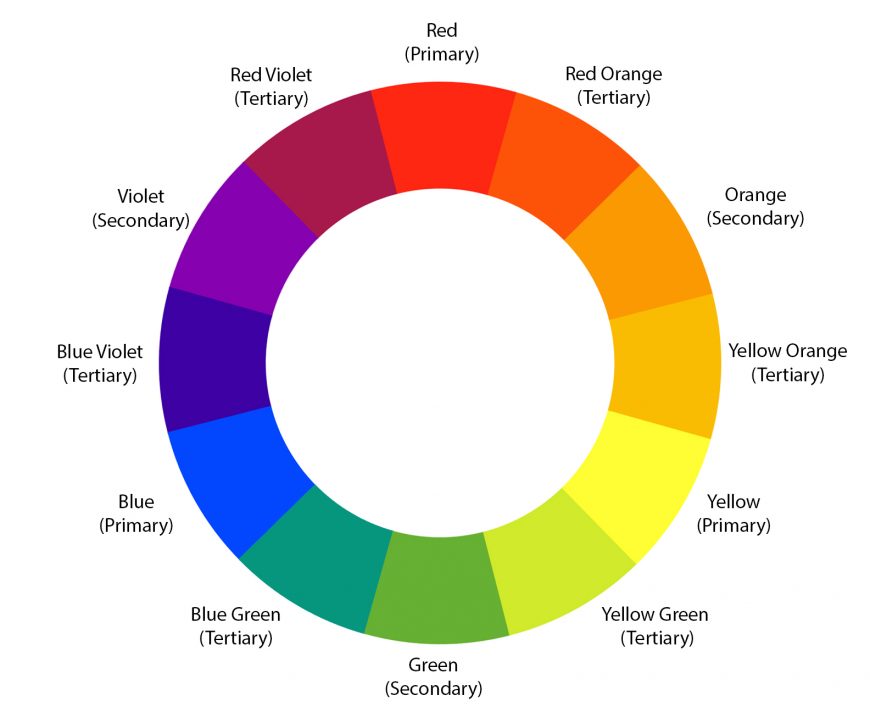

While Futurist poets added concrete aural and visual dimension to their poems, Futurist artists worked to expand the sensory appeal of their works beyond the visual. Carlo Carrà published a manifesto in which he called for painters to express sounds and smells through the use of shape and color. He claimed that all sounds and smells are dynamic vibrating intensities that provoke mental shapes and colors. This is a reference to a well-known perceptual phenomenon known as synesthesia, which can affect people in varying ways. Some people, for example, see colors when they hear music, while others smell a specific odor when they see a particular color. Synesthesia played an important role in the development of abstract painting in the early 20th century, most famously in the theories of Vasily Kandinsky.

Eliminating boundaries

The dynamic arrangement of words in Interventionist Demonstration creates a vortex of expressive significance that sucks the viewer into the composition. There are no still or stable places in the painting. The expanding, radiating composition, along with the inconsistent orientation of the lines of text, suggests that the sounds are coming at the viewer from all sides, dissolving the traditional boundary between viewer and artwork. This was a key goal of the Futurist painters, who wanted to create the sensation of immediacy and aimed to place the viewer in the center of the artwork.

Eliminating boundaries between the senses and between artistic media was also crucial for the Futurists. Carrà intended his painting to communicate emotion directly and synesthetically by means of color, shape, and composition, as well as by words. In addition to political slogans, most of the collaged words are references to Futurist themes, including the city and its crowds, sports and speed, sounds and music, colors and odors. There are numerous violent-sounding onomatopoeic words as well, including the title of Marinetti’s poem ZANG TUMB TUUUM pasted in the upper left.

A twirling dancer

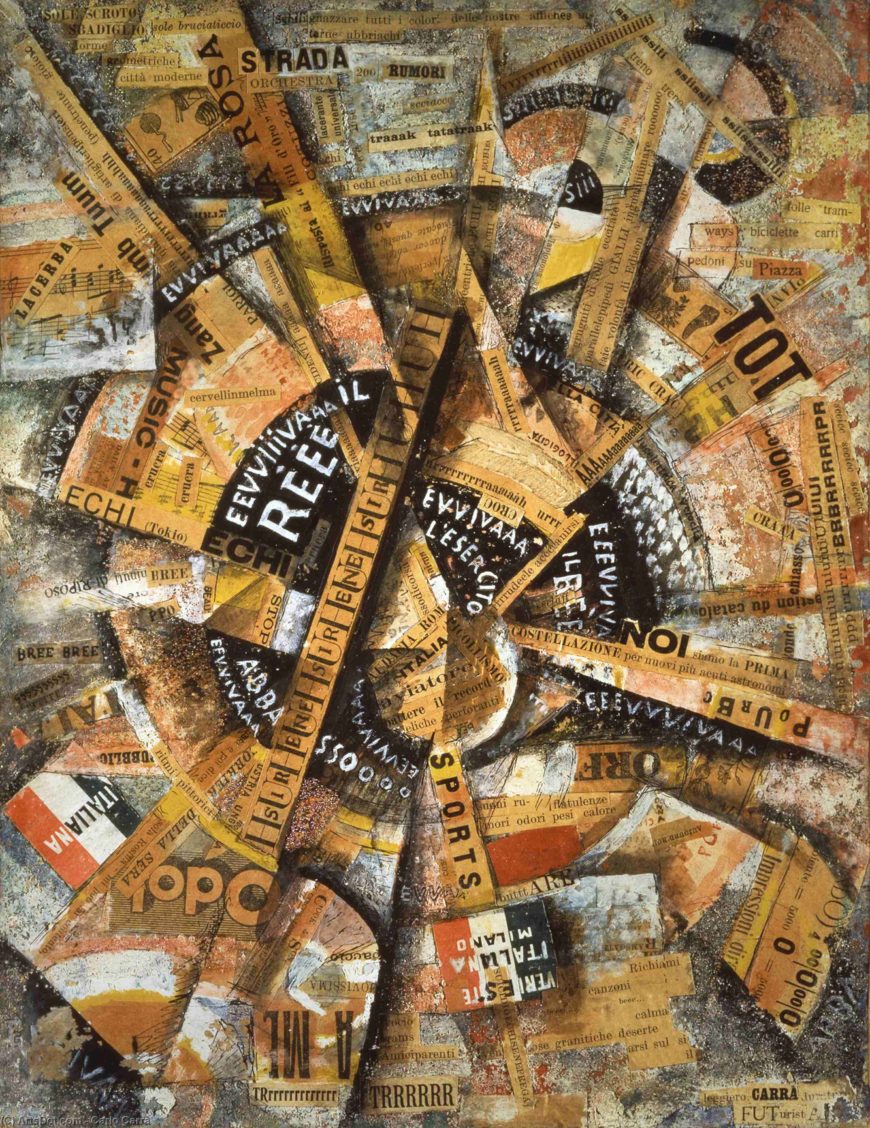

Gino Severini’s Serpentine Dancer uses an approach similar to that of Carrà’s Interventionist Demonstration. It represents the experience of watching a dancer in a nightclub. The abstract composition combines semi-circular arcs accompanied by acute triangles and stark contrasts of black and white. The forms of the drawing are comparable to Severini’s Sea = Dancer, painted only a few months earlier.

Reinforcing the equivalencies of words, sounds, and colors, the drawing includes many names of colors (verde, bleu, giallo, azzurro), as well as onomatopoeic sounds like TTATTA and SZSX. Words of different sizes are woven through the image, creating repeating patterns, echoing shapes in contrasting tones, and contributing both sound and meaning.

Severini indicated the twirling of the dancer with both repeated arcs and the words giro rapidissimo (rapid turn) and profondita spirale (deep spiral). Luce (light), calor (heat), and odore (odor) evoke the sensory experience of being in the nightclub. Piogga di fuoco artificiale (rain of fireworks), palla mauser sililo lacerazione (hissing Mauser pistol shot) and penetrazione luminosissima szszsz (luminous penetration) slash through the image in a white triangle that pierces the heart of the image. They remind us that for the Futurists any mass activity, including the pleasures of nightclubs and dancing, went hand in hand with a desire to incite violence, riot, and war.

On the battlefield

Painted a year later, Severini’s Cannon in Action uses similar techniques to communicate the experience of soldiers on the battlefield in World War I. Rather than representing the twirling of a dancer, this composition explodes out from the center in curves and arcs that convey the power and noise of a cannon firing. In keeping with the Futurists’ love of machinery, a cannon and armored vehicle dominate the scene with soldiers serving as their faceless accessories. Written words follow the painted forms, and most are informational and descriptive, just as the painting is largely representational rather than abstract. For example, the phrases written in the cloud of smoke behind the cannon are all comments on the horrible smell.

The Futurists’ parole in libertà and the development of free word painting arose from their desire to break down the divisions between different art forms to communicate feeling directly. Words, sounds, images, shapes, and colors were all used to convey the intensity of experience and bring the viewer into the heart of the action, be it participating in a crowd in a city square, dancing in a nightclub, or joining artillery men on a battlefield.

Notes:

- Translated in Christine Poggi, In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention of Collage (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), p. 207.

Additional resources:

Read about “words in freedom” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s Checklist blog

Read Carlo Carrà’s manifesto, The Painting of Sounds, Noises, and Odors

Read Filippo Marinetti’s Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature

Umberto Boccioni and the Futurist City

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

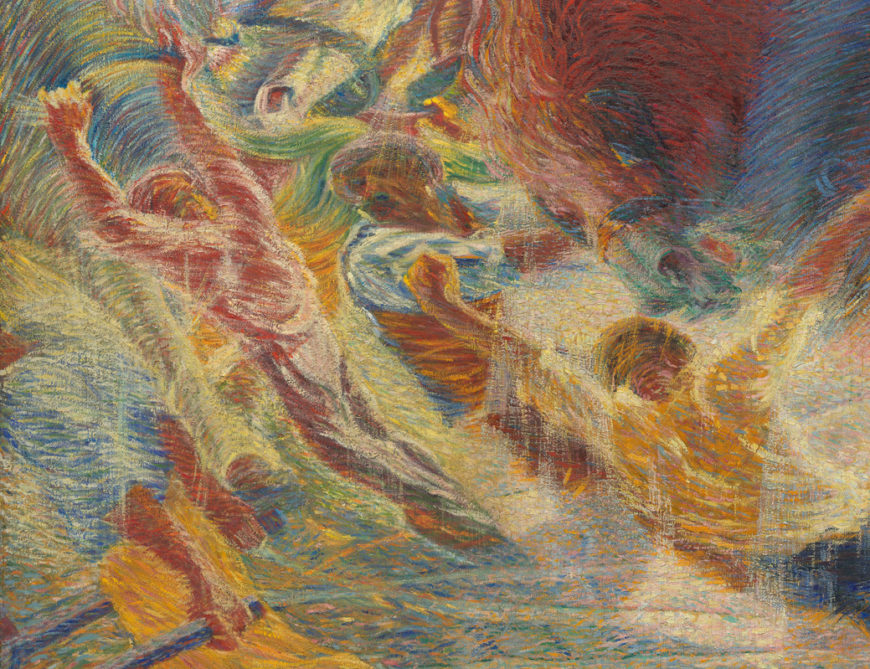

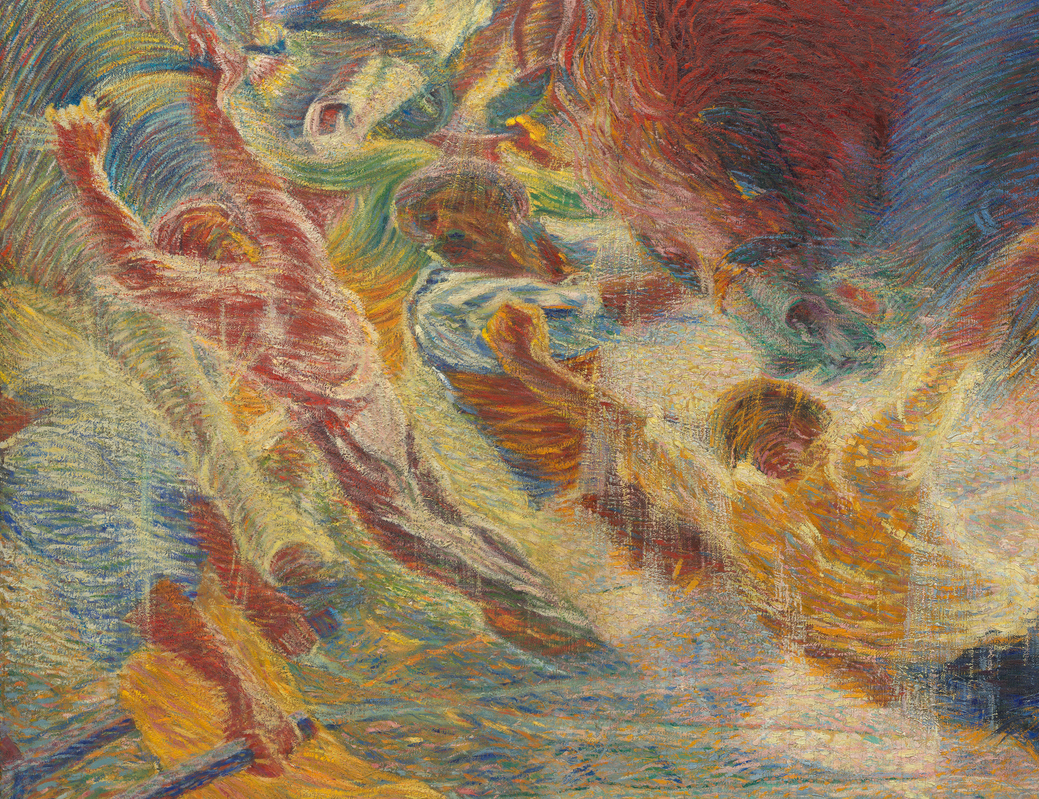

At almost ten feet wide, Umberto Boccioni’s The City Rises projects an image of overwhelming power. Huge workhorses surge across the canvas, their abstracted bodies dissolving into the space and light while their harnesses point upward like wings. Surrounding the enormous beasts, straining workmen in dynamic, elongated postures also partly dissolve into the vibrant, swirling brushstrokes that cover the painting’s surface. Boccioni has turned a construction site into a symbolic image of the powerful forces underlying the modern city.

Like the hooves of enormous steel horses

The painting contains a striking contradiction. It represents the construction site for a new electric power plant on the outskirts of Milan, Italy’s first modern industrial city. In the upper portion of the painting you can see the building under construction, tall smokestacks and, on the left, an electric tram. In the foreground, however, the scene is far from modern in its depiction of the brute power of human and animal labor rather than the power of machines. This contrast between the modern city and the physical labor required to construct it reflects Italy’s somewhat belated industrialization in the early 20th century.

The Futurists were outspoken supporters of Italy’s modernization. Led by the poet Filippo Marinetti, they demanded an end to the idolization of Italy’s dead past and called for the destruction of museums, libraries, and cultural monuments. They glorified modern technology, electricity, steel, and the speed of automobiles, trains, and airplanes. In addition, they promoted an aggressive masculinity and explicitly rejected feminism.

Boccioni’s paintings often seem to directly reflect Marinetti’s poetic imagery:

We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot; we will sing of the multicolored, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capitals; we will sing of the vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons; greedy railway stations that devour smoke-plumed serpents; factories hung on clouds by the crooked lines of their smoke . . . deep-chested locomotives whose wheels paw the tracks like the hooves of enormous steel horses . . .

Filippo Marinetti, “The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism,” translated by R. W. Flint, reprinted in Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (London: Blackwell, 2003), p. 148.

Painting universal dynamism

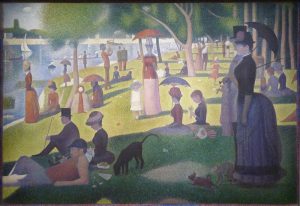

In addition to the roiling forms of the abstracted horses, The City Rises conveys the intense energy of the modern city and its workers by using bright color. The paint is applied using a modified divisionist technique (developed by French 19th-century Post-Impressionists, most notably Georges Seurat), in which small brushstrokes of complementary colors create a bright, flickering surface. There are no shadows; instead, swirls and rays of white paint overwhelm the figures with glowing light.

In keeping with Boccioni’s conception of a universal dynamism uniting all things, the flecks of paint suggest molecules of physical matter constantly changing to form new objects and energy. Nothing appears stable as the composition surges upward. The figures create powerful diagonals rising from right to left in the foreground. A second diagonal rises from left to right in the background, where the scene recedes into cloudy, angled vistas of industrial smokestacks.

The power of the masses

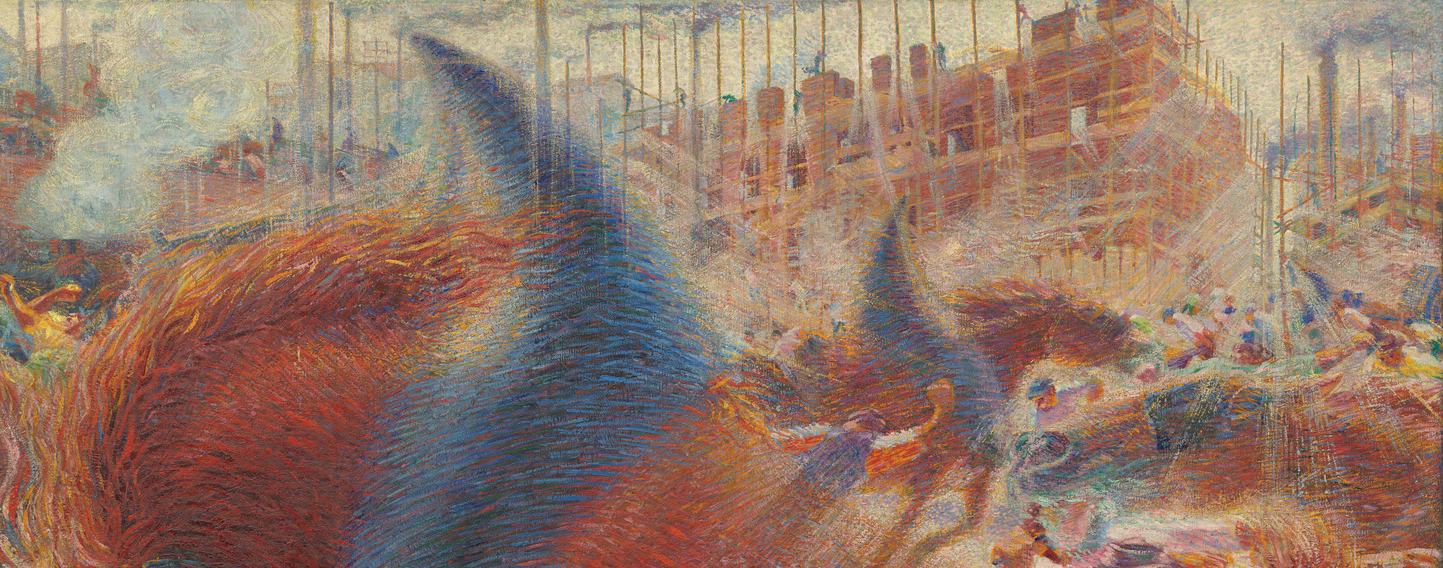

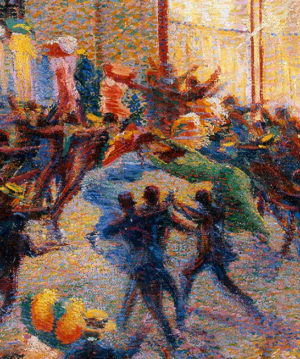

The figures in The City Rises have no faces and do not represent specific individuals. They are part of the city’s crowd, units in a potentially overwhelming force — the new masses of the modern city. The Futurists celebrated the vigor of the urban masses and even tried to incite riot and rebellion by insulting their audiences during aggressive public performances of their poetry and manifestos. We can see this side of the Futurists’ interests in another Boccioni painting, Riot in the Galleria, made while he was working on The City Rises.

In terms of subject and location, Riot in the Galleria is almost the polar opposite of The City Rises. Instead of a daytime construction site in the new industrial suburbs, it depicts a nighttime scene in a popular shopping arcade, the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, in the heart of Milan’s old city. The people, although equally faceless, are well-dressed and implicitly middle-class. The men wear suits and ties, the women are fashionably attired in bright colors and large fancy hats. Bright orbs of electric light glow in the upper half of the painting and illuminate the crowd outside a glass-fronted cafe.

In his “Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto” Boccioni declared:

We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot; we will sing of the multicolored, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capitals; we will sing of the vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons; greedy railway stations that devour smoke-plumed serpents; factories hung on clouds by the crooked lines of their smoke . . . deep-chested locomotives whose wheels paw the tracks like the hooves of enormous steel horses . . .

Filippo Marinetti, “The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism,” translated by R. W. Flint, reprinted in Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (London: Blackwell, 2003), p. 148.

Painting universal dynamism

In addition to the roiling forms of the abstracted horses, The City Rises conveys the intense energy of the modern city and its workers by using bright color. The paint is applied using a modified divisionist technique (developed by French 19th-century Post-Impressionists, most notably Georges Seurat), in which small brushstrokes of complementary colors create a bright, flickering surface. There are no shadows; instead, swirls and rays of white paint overwhelm the figures with glowing light.

In keeping with Boccioni’s conception of a universal dynamism uniting all things, the flecks of paint suggest molecules of physical matter constantly changing to form new objects and energy. Nothing appears stable as the composition surges upward. The figures create powerful diagonals rising from right to left in the foreground. A second diagonal rises from left to right in the background, where the scene recedes into cloudy, angled vistas of industrial smokestacks.

The power of the masses

The figures in The City Rises have no faces and do not represent specific individuals. They are part of the city’s crowd, units in a potentially overwhelming force — the new masses of the modern city. The Futurists celebrated the vigor of the urban masses and even tried to incite riot and rebellion by insulting their audiences during aggressive public performances of their poetry and manifestos. We can see this side of the Futurists’ interests in another Boccioni painting, Riot in the Galleria, made while he was working on The City Rises.

In terms of subject and location, Riot in the Galleria is almost the polar opposite of The City Rises. Instead of a daytime construction site in the new industrial suburbs, it depicts a nighttime scene in a popular shopping arcade, the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, in the heart of Milan’s old city. The people, although equally faceless, are well-dressed and implicitly middle-class. The men wear suits and ties, the women are fashionably attired in bright colors and large fancy hats. Bright orbs of electric light glow in the upper half of the painting and illuminate the crowd outside a glass-fronted cafe.

In his “Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto” Boccioni declared:

Our renovated consciousness does not permit us to look upon man as the center of universal life. The suffering of a man is of the same interest to us as the suffering of an electric lamp, which with spasmodic starts, shrieks out the most heart-rending expressions of color. The harmony of the lines and folds of modern dress works upon our sensitiveness . . .”

Umberto Boccioni, “Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto,” Reprinted in Art in Theory 1900-2000, p. 151.

Riot in the Galleria fully demonstrates Boccioni’s claim that light and clothing are as interesting as people.

The cause of the riot is unknown. Two women dressed in blue and green fight outside the cafe, while three men struggle together in front of them. A large crowd surges in from the left with their arms raised, while a group of barely individualized figures gestures behind the fighting women. Figures on the periphery run both towards and away from the central group. The scene is depicted from a safe distance, and we look down at the melee as non-involved spectators.

Although a riot is potentially dangerous, the painting is overwhelmingly cheerful with its bright patterns of divisionist colors. The strong verticals of the arcade’s architecture loom over the frenzied crowd in the lower half of the painting, providing a sense of balance, and enhancing our sense of psychological distance.

The scene is exciting without appearing threatening. This rather callous approach to a street brawl reflects the Futurists’ conviction that riot, revolution, and war were cleansing; they would sweep away the failures of the past and renew the world.

A shift in style

A slightly later painting of an urban scene, The Street Enters the House, represents a major shift in Boccioni’s style prompted by his exposure to Cubist techniques during a 1911 visit to Paris. The fractured representation of objects and space in Salon Cubism was not only more current than divisionism, it was an effective means to convey the Futurists’ modern concepts of space and time.

Like many of the Salon Cubists, the Futurists were influenced by the philosophy of Henri Bergson as well as by recent scientific discoveries, such as X-rays and Einstein’s new physics. They embraced the concepts of simultaneity and universal dynamism and sought new ways to depict the vital energy of the universe in painting. Boccioni declared that space no longer existed and that he would paint dynamic sensation itself rather than isolated objects. He also promised to put the spectator in the center of the picture.

The Street Enters the House is a literal depiction of that promise. It represents a woman in the center of the picture watching men constructing a factory from her balcony. Fractured buildings frame the work site in the center, while a kaleidoscopic array of girders, bricks, and figures thrust upward, surrounding and, in places, penetrating the woman’s body. She leans somewhat precariously over the dizzying view, and we hover even more insecurely just above her. Confronted by the complexity of the scene and the vibrant colors, we are drawn in to psychologically engage with its urban confusion, a very different effect from the distant vantage point of Riot in the Galleria.

Boccioni’s desire to place the spectator in the center of the painting reflects his conception of a reality in which time and space are in constant flux, and that he as an artist intuits the vital forces that flow through all things. By depicting the excitement of rioting crowds, the construction of the new city, and the electricity that powered it, he conveyed his sensitivity to the new forms and energies of the modern world.

Additional resources:

Read about Futurism’s interest in riots at the Guggenheim Museum’s Checklist blog

Read more about Umberto Boccioni at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space

The Futurists wanted art to break from the Classical and Renaissance styles still dominant in Italy at the start of the Twentieth Century. For some, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space shows a figure striding into the future. Its undulating surfaces seem to transform before our eyes. About fifty years after Charles Darwin introduced the theory of evolution and about thirty years after Nietzsche described his “super-man,” Boccioni sculpted a future-man: muscular, dynamic and driven.

Motion as Form

The face of the sculpture is abstracted into a cross, suggesting a helmet, an appropriate reference for the war-hungry Futurists. The figure doesn’t appear to have arms, though wing-like forms seem to emerge the rippling back. However, these protrusions are not necessarily even a part of the figure itself, since Boccioni sculpted both the figure and its immediate environment. The air displaced by the figure’s movement is rendered in forms no different than those of the actual body. See, for example, the flame-like shapes that begin at the calves and show the air swirling away from the body in motion.

This idea of sculpting the environment around a figure is expressed in Boccioni’s “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture” (1912) and shows the influence of the sculptor Medardo Rosso, an Italian contemporary of Auguste Rodin who worked in Paris (and who was becoming more popular back in Italy in this period thanks to the efforts of sometime-Futurist Ardengo Soffici. Rosso made impressionistic plaster or bronze busts, covered in wax, of people in Paris, in which the figures merge into the space around them, as seen in his Impressions of the Boulevard: Woman with a Veil, 1893. Unique Forms of Continuity in Space has also been compared to Rodin’s armless Walking Man of 1907.

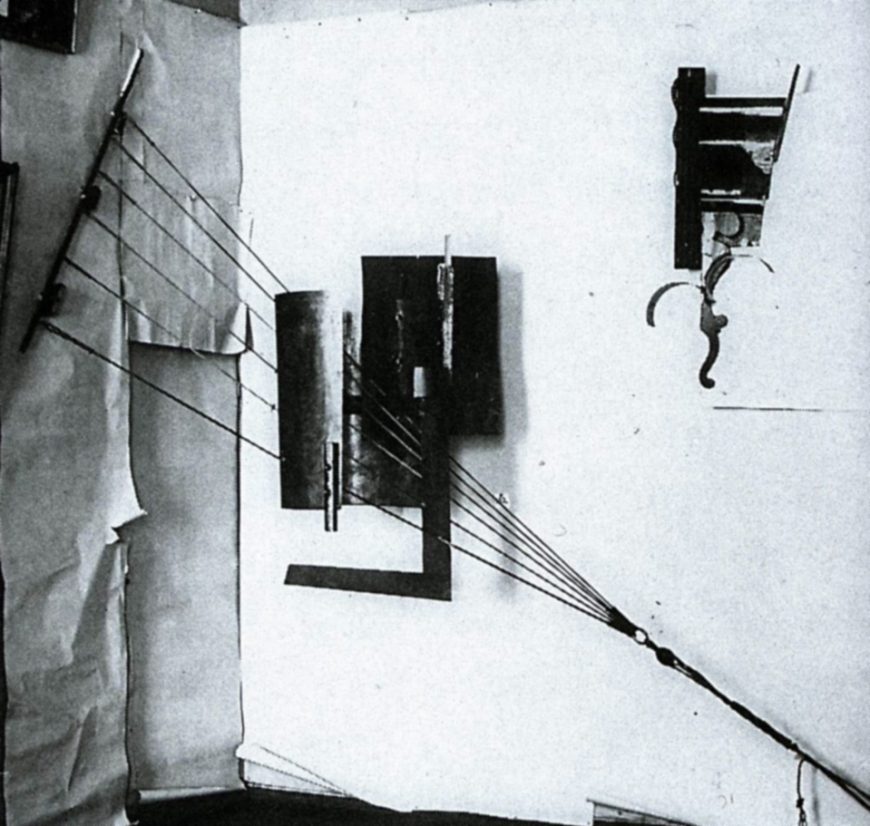

Unique Forms is one of a series of sculptures of striding figures that Boccioni created in 1913. Up until 1912, Boccioni had been a painter, but after visiting Paris and the seeing sculptural innovations like Braque’s three-dimensional Cubist experiments in paper, Boccioni became obsessed with sculpture. His striding sculptures continued the theme of human movement seen in his paintings such as Dynamism of a Soccer Player, 1913.

Movement was a key element for Boccioni and the other Futurists, as the technology of transportation (cars, bicycles, and advanced trains) allowed people to experience ever greater speeds. The Futurist artists often depicted motorized vehicles and the perceptions they made possible—the blurry, fleeting, fragmentary sight created by this new velocity.

Breaking his Own Rules

Unlike fellow Futurist Giacomo Balla, who used repeated forms to represent movement, in work such as Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912), Boccioni synthesized different positions into one dynamic figure. Although Unique Forms of Continuity in Space is the most famous Futurist sculpture, there are some aspects of the work that do not fit neatly with the artists’ declarations. For example, three years before he made this sculpture, Boccioni and the other Futurist artists had banned the painting of nudes for being hopelessly mired in tradition—and Unique Forms is a nude male, albeit one abstracted through exaggerated muscles and possibly shielding its head with a helmet.

Boccioni also breaks rules from his “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture” where he declared that Futurist sculpture should be made of strong, straight lines, “The straight line is the only way to achieve the primitive purity of a new architectonic structure of masses or sculptural zones.” Clearly, he had not yet recognized the potential for the dynamic curves so powerfully expressed here. His manifesto also states that sculpture should not be made from a single material or from traditional materials such as marble or bronze.

Bronze or Plaster?

Boccioni produced several mixed media sculptures and the original Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, was, like the majority of his sculptures, made of plaster. The bronze versions we are so familiar with are casts made long after the artist’s death in 1916. The original white plaster sculpture, today in São Paulo, looks more transient and delicate than the later bronze casts, and is thus far more fitting for Futurism, since many Futurists claimed to want their works of art destroyed by more innovative artist successors, rather than preserved in a museum.

Unique Forms appears on the Italian 20-cent Euro coin and is both Futurism’s most famous symbol and a reminder that the movement itself was dynamic and did not always follow its own declarations. The Futurists sought to clear away the legacy of art’s history so that the future could come more quickly, but Unique Forms has often been compared to the ancient Greek Nike of Samothrace and Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne. The Futurists wanted to destroy the museums, but in the end, their work was added to the canon of Italian sculpture.

“Museums: absurd abattoirs for painters and sculptors who ferociously slaughter each other with colour-blows and line-blows along the disputed walls!”

–F.T. Marinetti, “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism,” 1909

Additional Resources:

This sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art, NY

Ester Coen, Umberto Boccioni (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988)

This sculpture at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Medardo Rosso, Impressions of the Boulevard: Woman with a Veil, 1893 (Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

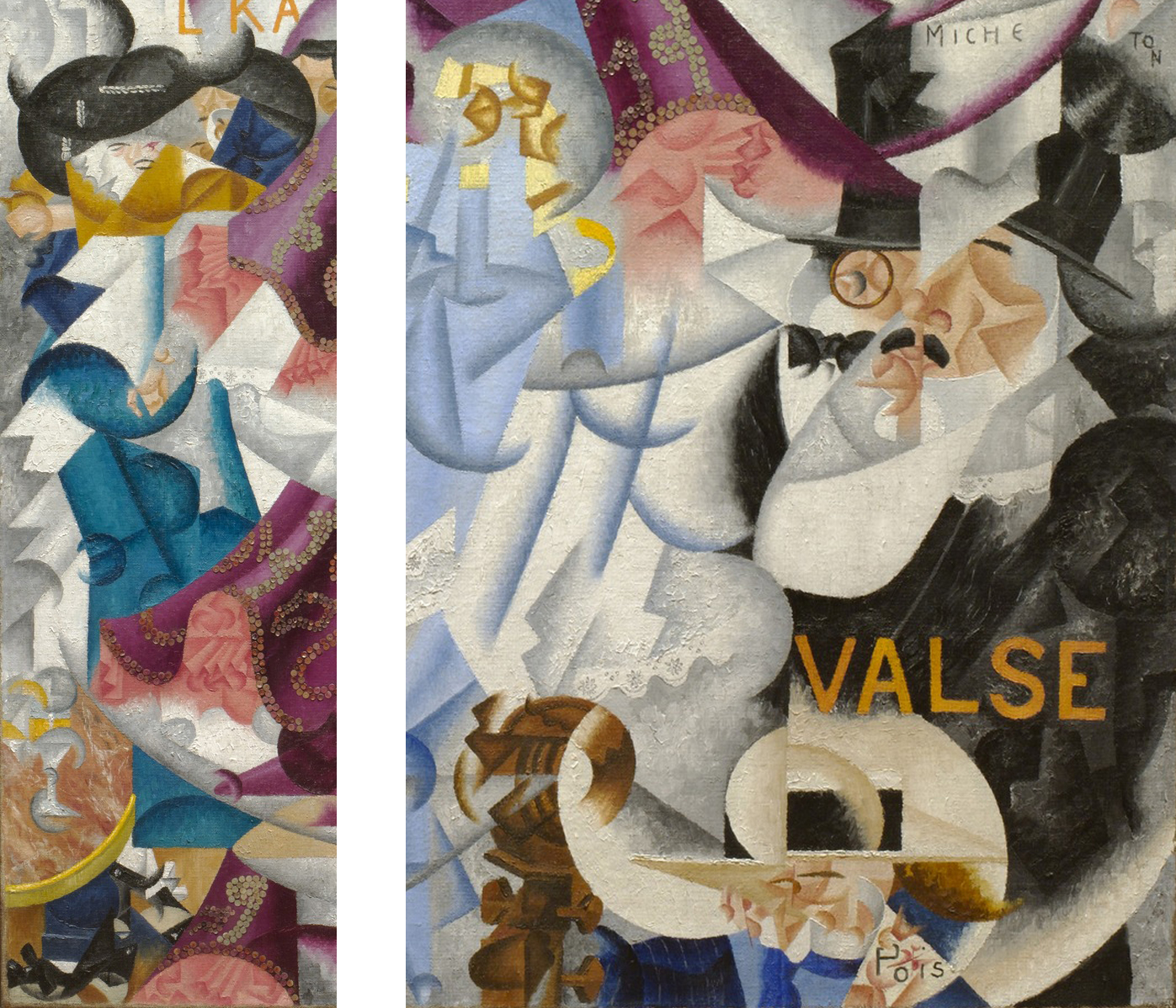

Gino Severini, Dynamic Hieroglyph of the Bal Tabarin

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

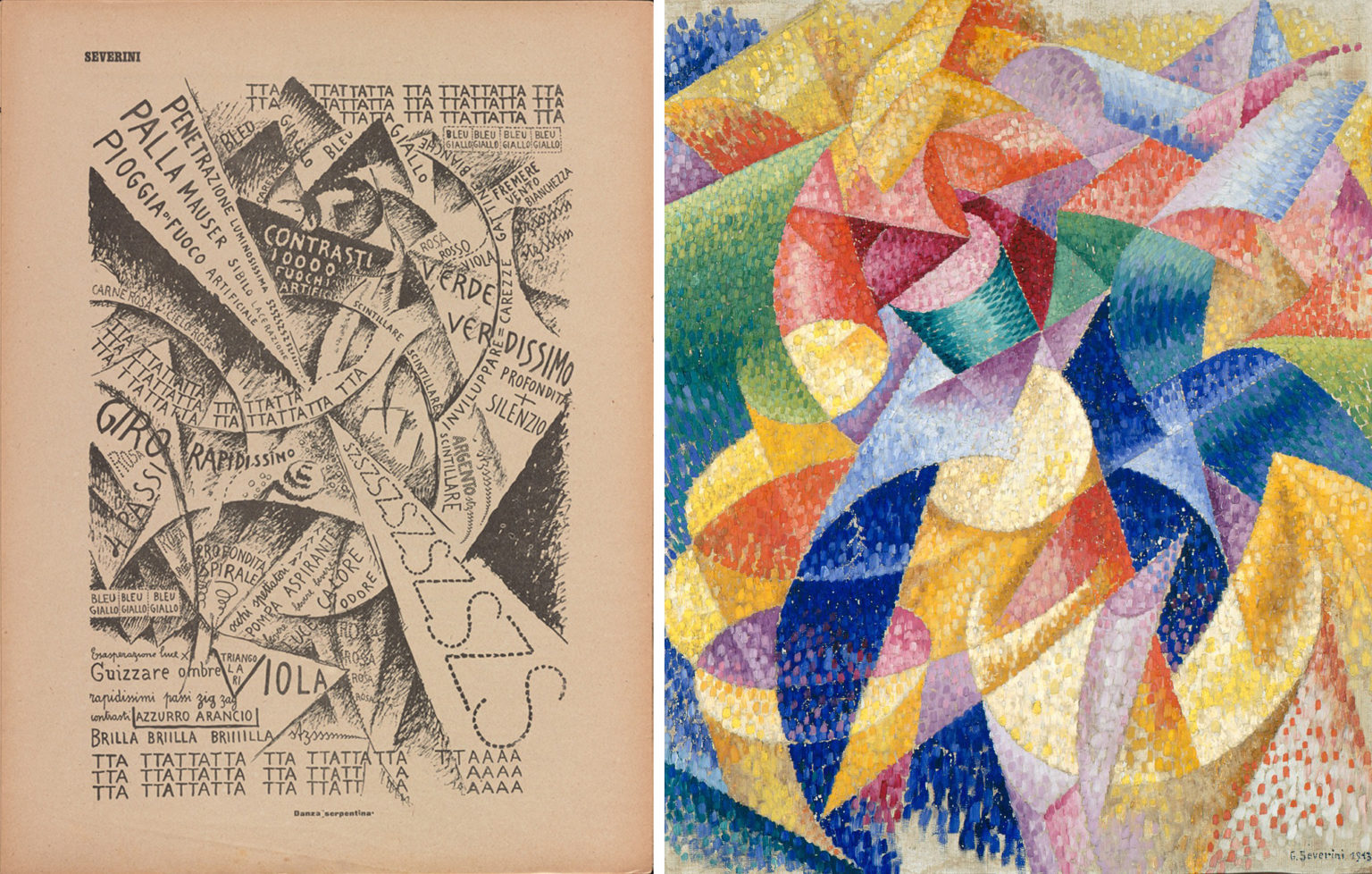

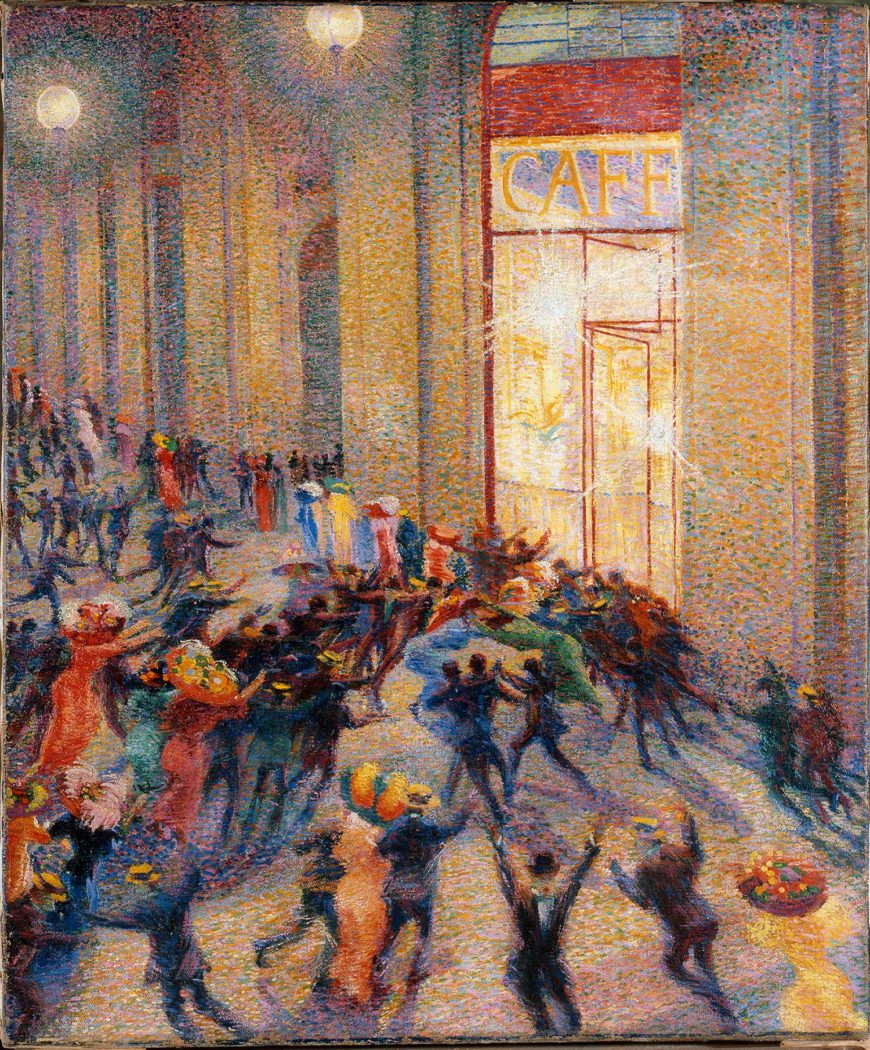

Gino Severini’s Dynamic Hieroglyph of the Bal Tabarin draws us into the frenzied excitement of a Paris nightclub. Combining a Cubist technique of fractured planes with the use of repetition, Severini creates a brilliant kaleidoscope of partially-glimpsed figures in motion. Dominating the center of the painting are two dancing women —one with blond curls on the left, the other with dark hair on the right— and a swirling pink and purple dress. Looping patterns of real sequins decorate the dress, adding to the shimmering play of light in the painting.

Adopting Cubist techniques

The painting’s emphasis on dynamism is characteristic of Italian Futurism, as is the subject of modern urban life. The Futurists embraced the energy of the modern city, its crowds and electricity. They adopted Cubist techniques to convey the sense of movement in time, while rejecting what they considered the more static and analytic approach of Cubist painters. Whereas in Cubist paintings the use of multiple, fragmentary views of things suggests the viewer is moving around the object, in Futurist paintings it is the scene that is moving around the viewer.

Severini lived in Paris and was friends with many avant-garde painters, including Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. In Dynamic Hieroglyph he adopts their recent innovations by including painted words and collaging sequins onto the painting’s surface. Severini’s painting is, however, markedly different from Synthetic Cubism in its subject matter as well as its brilliant colors and decorative qualities. It is closer to the paintings of the Salon Cubists, such as Jean Metzinger’s Dancer in a Café. However, Severini’s emphasis on the whirling dynamism of the scene differentiates his Futurist approach from Metzinger’s more static and balanced Cubist composition based on an underlying grid.

Like many Salon Cubists, Severini was influenced by the popular philosopher Henri Bergson. Dynamic Hieroglyph was painted from memory, and in keeping with Bergson’s ideas, it attempts to convey the painter’s intuitive vision of reality in which time and space are suffused with memory and sensation. The dancers’ movements fragment and fill the painting with energy and traces of their momentary presence. They embody Bergson’s concept of élan vital, the vital force of the universe uniting all matter.

A frenetic scene

Severini conveys the dancer’s movements through the repetition and fragmentation of forms. For example, we see parts of the head of the dancer on the left in three or four different positions as she dances. The swirling movements of the dancer’s skirts are depicted as fragments of patterned purple, pink, light blue, and white material appearing in various locations. In addition, abstract curves and angles suggest the changing shapes of the fabric as the dancer moves through space. A bright circle of white dominates the center of the painting, suggesting a spot-lit dance floor and the swirling circular movements of the dancers.

On the periphery of the dancer’s orbit many other figures and objects complete the frenetic scene of a nightclub in full swing. In the lower left corner is a Cubist tabletop still life with martini glasses, over which a woman in a blue dress and black hat stands laughing. In the lower right corner is a mustachioed man wearing a monocle, black suit, tie, and top hat. Directly in front of him is a Cubist rendering of the scroll and tuning pegs of a bass.

Placing the viewer in the center

In depicting the upper portion of a bass projecting into the painting Severini was copying a device frequently used by two earlier innovative painters of dancers and Paris nightlife, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Edgar Degas.

In their works the cropped tops of musical instruments were intended to give the viewer a sense of being present in the audience and looking over the musicians at the stage. Severini’s Dynamic Hieroglyph, in keeping with the Futurists’ goal of placing the viewer in the center of the painting, attempts to provide an even more intense sensation of presence and immediacy through its fractured forms, brilliant colors, and glittering sequins.

Streamers and national flags are draped across the upper portion of Dynamic Hieroglyph, intertwining with suggestions of abstracted figures and light fixtures. Among these chaotic forms several enigmatic, but easily legible, figures appear: a black cat head, a North African man riding a camel, and a nude woman riding a pair of scissors. These figures may refer to cabaret acts or themed costume parties that were often held in the fashionable nightclub.

Severini also included a number of words in the painting, a device he adopted from Picasso’s and Braque’s Cubism. The two most prominent words, “polka” and “valse” (waltz), directly refer to the painting’s subject, while others have less obvious relevance, and may refer to Severini’s personal experiences and memories.

Decadent pleasures

Paris nightlife was an ideal subject to display the Futurists’ fascination with the energy of modern urban crowds and the novel effects of electric lighting. Umberto Boccioni’s The Laugh depicts a crowded club splintered into shards of garish color under the projecting rays of electric lights. A smiling woman, usually identified as a cocotte or fashionable prostitute, wears a large red hat and dominates the scene in the upper left corner.

In the center of the painting we see the huge yellow feather and elaborate hat of another woman. The somewhat less visible faces of three men surround the women, and we can also see fragments of other figures, hands, stemmed glassware, and fruit in the kaleidoscope of colorful planes. Receding into the background are more tables with glasses, and suggestions of figures enjoying themselves under the glowing light bulbs.

Severini’s Bal Tabarin and Boccioni’s The Laugh are Futurist updates of Toulouse-Lautrec’s At the Moulin Rouge, which also depicts the decadent pleasures of Paris nightclubs. The compositions of all three are designed to make the viewer feel as if they are present in the scene, but Toulouse-Lautrec’s is comparatively distanced and reserved. Severini and Boccioni use brilliant colors, abstraction, fragmentation and repetition of forms to create a vibrant whirling energy that seems to fully surround the viewer and encourage us to participate in the contagious hilarity of the crowded nightclub.

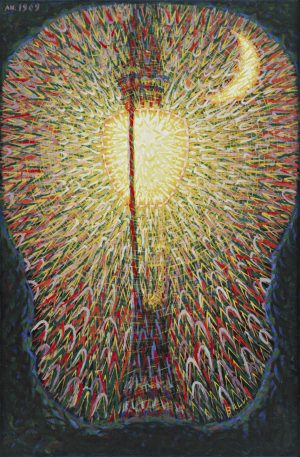

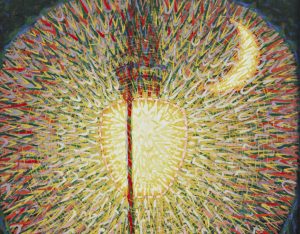

Giacomo Balla, Street Light

If you were an artist preparing to paint a picture, depicting a lamp post might not be your first choice of subject matter. It certainly wouldn’t have been the go-to subject for most painters in the early twentieth century: a human figure, a landscape, or a still life would have been more standard choices. But in 1910 or 1911, the Futurist painter Giacomo Balla painted a large canvas displaying a huge electric street light, on a canvas that is over five feet tall, with a diminutive moon in the corner. Why would he have made such a choice?

Loving the future, hating the past

As a member of the Italian Futurist movement, Balla was passionately invested in making art that reflected “the future”: that is, the increasingly industrialized and technological world of the early twentieth century. Futurism swept onto the European art scene in 1909, when an Italian poet named Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism” in newspapers in Italy and France. In it, he declared that reverence for history and past artistic traditions needed to be abandoned in order to move society and art decisively into the modern age. In embracing modernity and violently dismissing Italy’s honored artistic heritage (“Set fire to the library shelves! Turn aside the canals to flood the museums!” he wrote), Marinetti initiated one of the most bombastic and aggressive avant-garde movements of his time. The writer prized new technology rather than tradition, and sought to create a climate of violent revolution rather than one of comfortable stability. The artists who gathered around him aimed to make art that would showcase modern mechanical developments like airplanes and automobiles, especially because they could provide the viewer with new experiences like the speed of these new modes of transport.

Balla’s Street Light, in this sense, is a sort of demonstration piece for the Futurist movement. Balla has rejected traditional subject matter in this painting, and instead has painted an object that is forthrightly modern and technological: one of the new, electric street lamps that were just being installed at this time in Rome, where Balla lived. The introduction of electrified city lighting must have been an exciting sign of technological advancement for the Futurists, and also a powerful symbol of how the ancient city of Rome was finally abandoning its past and entering the modern age.

The small crescent moon Balla included in his painting is also an illustration of Futurist ideas. Just as the street light stands for the future in the picture, the small moon stands for the past. In part Balla means this in a literal sense. In the past people relied on the moon to see at night; in modern times we rely on electricity. But Balla is also alluding to a number of Marinetti’s writings in which the moon was used as a symbol for the artistic traditionalism that the Futurists wanted to destroy. Summed up in his slogan “Let’s kill the moonlight!” Marinetti attacked the gentle light of the moon and its long association with traditional romance and sentimentality. He condemned past generations of artists and poets as “lovers of the moon,” and called for a more modern and aggressive symbol—like a racing car or a train—to take its place. Balla’s Street Light, which overpowers the moon’s dim light, serves as a visual equivalent to these ideas.

Balla’s style

Balla was one of the older members of the Futurist movement, and he had already established a career as a painter by 1909 when Futurism was founded. Before joining the Futurists, Balla had been working in one of the styles popular in late nineteenth-century Europe, which art historians often term “post-Impressionism.” In Italy one of the most prominent post-Impressionist styles was “Divisionism,” so named because it was based on dividing colors into their constituent parts on the canvas and letting brushstrokes remain visible instead of smoothly blending them together (Georges Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte, above, is one of the best-known examples of Divisionism). Since Street Light was painted early in the Futurist movement, Balla’s style here is still essentially Divisionist in its approach. Balla uses obvious, bold brushstrokes in a repeated V-pattern to illustrate the light and energy radiating from the lamp. The saturated colors of Street Light—from the almost blinding white and yellow at the center of the lamp, to the cooler hues further from the light’s bulb—are also typically Divisionist.

Street Light seems to have been enthusiastically received by Balla’s fellow painters when it was completed. In a group manifesto written in 1910, titled “Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto,” the work is showcased as a superb example of Futurist subject and style: the group exalts the “electric lamp, which, with spasmodic starts, shrieks out the most heartrending expressions of color.”

Despite these claims, Balla and the other Futurist painters would soon abandon the Divisionist style, since it ultimately seemed too tied to past generations to be truly “of the future.” After the Futurists visited Paris together in 1911, several of them adopted aspects of Cubism, though they altered the technique to focus more clearly on Futurist concerns like modern technology, movement, and speed. Balla, however, began to earnestly explore how one might paint movement in other ways. At first, in a series of paintings in 1912, he showed movement by painting many small increments of time in a series, as in Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (above). Later, in 1912 and into 1913, Balla entered an exploratory abstract phase, painting the movement of cars driving, birds in flight, and even the movement of light itself, via geometric shapes, dynamic lines, and abstract patterns of color. These paintings, such as Abstract Speed (below), put Balla at the forefront of European artists who were pioneering total abstraction in their work. Street Light, painted just a few years before these experiments, was a visual manifesto that ultimately helped drive the Futurist movement in these new directions.

Additional Resources:

This painting at The Museum of Modern Art

Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery

Carlo Carrà, Funeral of the Anarchist Galli

“We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure and by riot” declared F.T. Marinetti in his ‘Founding and Manifesto of Futurism’ (1909). Such crowds were increasingly common in the industrial cities of northern Italy, such as Milan, where the Futurists were based.

In this painting Carlo Carrà commemorates the death of Angelo Galli during a strike in Milan and the subsequent funerary parade to the cemetery, which erupted into violence between anarchists and the police. At the center of the canvas, Galli’s red coffin is held precariously aloft, surrounded by a chaotic explosion of figures clad in anarchist black, illuminated and dissected by light emanating both from the coffin and the sun.

Futurism’s anarchist roots

Carrà lived in Milan and was involved with anarchist groups; he was at the funeral and recalled the event in his memoirs La mia vita (1945):

I found myself unwillingly in the centre of it, before me I saw the coffin, covered in red carnations, sway dangerously on the shoulders of the pallbearers; I saw horses go mad, sticks and lances clash, it seemed to me that the corpse could have fallen to the ground at any moment and the horses would have trampled it. Deeply struck, as soon as I got home I did a drawing of what I had seen.

Carrà’s autobiography associated the funeral with the earlier 1904 strikes which had gained a mythological status in the history of Italian politics, but in fact the event took place two years later during a smaller strike, as chronicled in the Corriere della Sera on May 14, 1906. Writing his memoirs many years later—in 1945, as Fascism fell—Carrà may have been keen to associate himself with an important moment in Italian anarchism.

A Cubist redesign

The preparatory drawing for Funeral uses one-point perspective and combines detail and dynamism in its depiction of the scene. When Carrà began working on the painting in 1910, it may have originally looked similar to this drawing, but in 1911 the Futurist artists went on their first trip to Paris and saw examples of Picasso’s Cubism; upon returning Carrà changed his canvas to the fractured perspective we see in the painting today.

Nevertheless, the Futurists were keen to emphasize that their abstraction was quite different from that of the Cubists, stressing their dynamism as opposed to static analytical Cubism. In ‘The Exhibitors to the Public,’ the manifesto the Futurists published in the catalogue of their first exhibition in Paris in 1912, they wrote this statement, possibly referring to this picture:

If we paint the phases of a riot, the crowd bustling with uplifted fists and the noisy onslaughts of the cavalry are translated upon the canvas in sheaves of lines corresponding with all the conflicting forces, following the general law of violence of the picture.

Carrà’s redesign also brought the spectator closer to the action, in line with the Futurists’ desire to put the spectator “at the center of the picture,” a goal expressed in ‘Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto’ (1910). The bright dabs of paint on the surface of Carrà’s picture, rarely apparent in reproductions, also show Futurism’s debt to the Italian Divisionist painters who preceded them.

This interest in the direct relationship between the viewer and the painting is especially apparent when Funeral of the Anarchist Galli is compared with Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo’s Fourth Estate (Il Quarto Stato) (1898-1901), which has a similar subject.

A historic battle

Despite its formal novelty, Funeral is unusual for Futurism because its subject and grand scale make it essentially a history painting. Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the first director of the Museum of Modern Art, wrote just a year after the museum purchased the painting, “fundamentally, in its main lines and masses Carrà’s Funeral is as classically organized as a fifteenth-century battle piece by Paolo Uccello.” (Twentieth Century Italian Art, 1949).

After moving away from Futurism in 1916, Carrà became very interested in Uccello, writing a long article mentioning The Battle of San Romano in the Uffizi, one of three canvases of this battle by Uccello. Carrà could have been familiar with the other two versions before painting Funeral as he visited both the Louvre and the National Gallery in 1899-1900. The clash between the anarchists and the police is compositionally closest to the Uffizi version; the dominance of black and red recalls the Louvre version; and the melee of flag poles, lances and cranes jutting into the sky is present in all three.

Carrà’s painting has become an emblem of Futurism, both for its violent subject and formal novelty. Its relationships with anarchist politics, Cubism and battle paintings remind us of the diverse ideas circulating in early twentieth-century Europe.

Additional resources:

F. T. Marinetti, “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism” (1909), read by Charles Bernstein

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Horse

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Horse, 1914, bronze, 39-3/8 x 24 x 36 inches (99 x 61 x 91.4 cm) (Art Institute of Chicago)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Simultanism (Orphism)

Sonia Delaunay

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

Almost eleven feet wide, Sonia Delaunay’s Bal Bullier creates an overwhelming impression of brilliant color and movement. The composition juxtaposes rectangular geometric forms and circles with more fluid curved shapes, loosely structured across the canvas in a rhythmic pattern of dark and light verticals.

A modern dance hall

The Bal Bullier was a dance hall in Paris that Delaunay frequently visited with her husband, Robert. Her painting shows a scene of modern urban life comparable to those painted by the Impressionists in the late 19th century, such as Auguste Renoir’s Moulin de la Galette.

If you look closely at the dark shapes in the center you will see the abstracted forms of couples dancing the tango. The dance, which originated in sailors’ bars in Argentina, was very popular in Paris in the early 20th century. It is renowned for its erotic intensity and requires a very tight embrace between partners, which Delaunay represents in the interlocking curves of the figures.

Sonia’s Electrical Prisms is both a display of color relationships and an abstracted depiction of her first experience of electric streetlights on a Paris boulevard. The streetlights become discs of radiating color that permeate the entire canvas, but there are also suggestions of solid forms. A tall kiosk with books or magazines is on the left, and parts of some shadowy figures appear in the lower half of the painting, almost completely absorbed into the brilliant colors of the electric light.

Intuition vs. intellect

While Robert studied scientific color theory, they both described Sonia’s approach to their new style as intuitive. This is a cliché of traditional Western gender roles — the male as rational and intellectually inclined, the female as naturally gifted and intuitive — but it is a cliché that they both embraced.

Interestingly, in Western art theory color is thought to appeal directly to the senses, in contrast to drawing’s supposed appeal to the intellect; thus, Sonia’s purportedly intuitive approach to color was aligned with traditional Western conceptions of color’s role in art. It should be noted, however, that Sonia formally studied art for several years in a German academy and an art school in Paris, while Robert’s formal artistic training was limited to a two-year apprenticeship with a theatrical designer in Paris.

The influence of craft

Sonia’s use of color was also sometimes explained by another cliché of the early 20th century, the influence of peasant crafts on her work. Since the late 19th century, modern artists such as Gauguin had admired, and appropriated, the purportedly naive, untutored styles of peasant art, which were often vividly colored and non-naturalistic.

Sonia herself claimed that the patchwork blanket she made for her son in 1911 was inspired by peasant blankets she remembered seeing in Russia as a child. Its irregular grid of largely rectangular geometric forms was also similar to contemporary Cubist painting. Sonia saw her blanket as an important influence on her and Robert’s subsequent development of Simultanist paintings.

Abstraction and decoration

Sonia’s blanket and its influence raises a key issue for modern abstract art — its relationship to crafts and the decorative arts. The use of non-representational forms and patterns has a long history in Western crafts and decorative arts; it was the so-called fine arts of painting and sculpture that traditionally relied on representational subject matter. When modern painters began to use non-naturalistic colors and abstract forms in the early 20th century, one of their primary concerns was to prove that their paintings were not “mere” decoration. This is one reason why many of the first modern artists to embrace pure abstraction took so long do so and wrote extensive justifications, often claiming exalted spiritual motivations for their abstraction.

Abstraction and representation

Unlike many of their contemporaries who developed abstract painting styles that progressed from representation to pure abstraction, the Delaunays painted representational and non-representational Simultanist works at the same time. Modern objects such as the Eiffel Tower and airplanes as well as scenes of dance halls and rugby games were enveloped in the prismatic color planes of Simultanism. Like the Italian Futurists, the Delaunays created a post-Cubist style appropriate to the modern city, and Sonia expanded her art beyond the limits of the easel painting to engage with everyday life.

Going beyond painting

The same year that she painted Bal Bullier Sonia made herself a Simultaneous Dress. Like her earlier blanket, it was a colorful patchwork of geometric shapes, but the dress was made to be seen in public. She wore it to the dance hall with Robert, who also wore clothes in vivid contrasting colors. By attiring themselves in the colors and forms of their painting they became living, moving artworks, Simultanist human beings.

Sonia dreamed of transforming everything around her, and she created and exhibited bookbindings, home furnishings, and posters in the Simultanist style in 1913. After World War I, she became a very successful designer of clothing and interior furnishings, and colorful contrasts of geometric forms remained characteristic of her work.

A Simultanist book

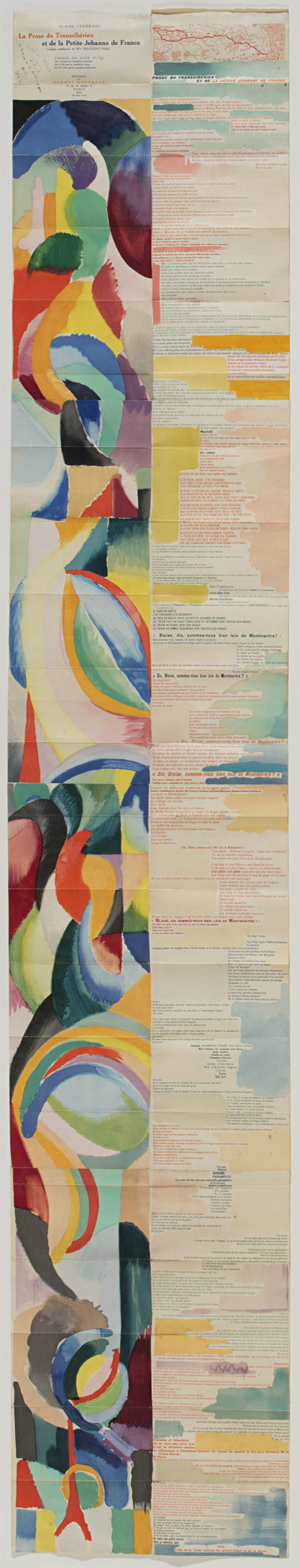

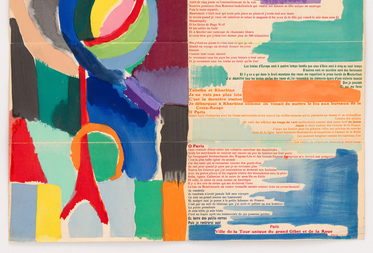

One of Sonia’s most famous early creations is the Simultanist book she designed in collaboration with the poet Blaise Cendrars titled La Prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France.

Unfolded, the book is six feet long. Delaunay and Cendrars initially intended to publish 150 copies, which opened together in a line would have equaled the height of the Eiffel Tower. The text of Cendrars’ poem is printed in multiple colors and varied fonts on the right, while Delaunay’s largely abstract Simultanist designs parallel it on the left, with panels of lighter colors also interspersed throughout the text.

The poem combines disjointed thoughts, repeated refrains, and references to a trip on the Trans-Siberian railroad, of which there is a map at the top. Time and place shift throughout the text, with Paris as a constant presence. Sonia’s colorful abstract forms swirl down the long sheet, looping into circles that visually echo the poem’s evocation of the train’s rolling motion.

The poem ends with a Paris scene next to the only clear representational form in the design – a red Eiffel Tower accompanied by a circle reminiscent of the giant Paris ferris wheel.

When fully unfolded, the designs on the left side seem to ascend like clouds of brightly colored smoke from the Eiffel Tower to the beginning of the poem at the top, where the viewer is led to read the poem down the right side. Thus, the open book creates a continuous circuit with the tower standing like an anchor at the bottom.

Simultanism was developed in a collaboration between Sonia and Robert Delaunay, but it extended well beyond that initial relationship. It became an approach to modern art and style that worked to bridge the distances between the visual arts and literature, the fine and decorative arts, and the art and spectacles of the modern urban world.

Additional resources:

Simultanism: Robert Delaunay

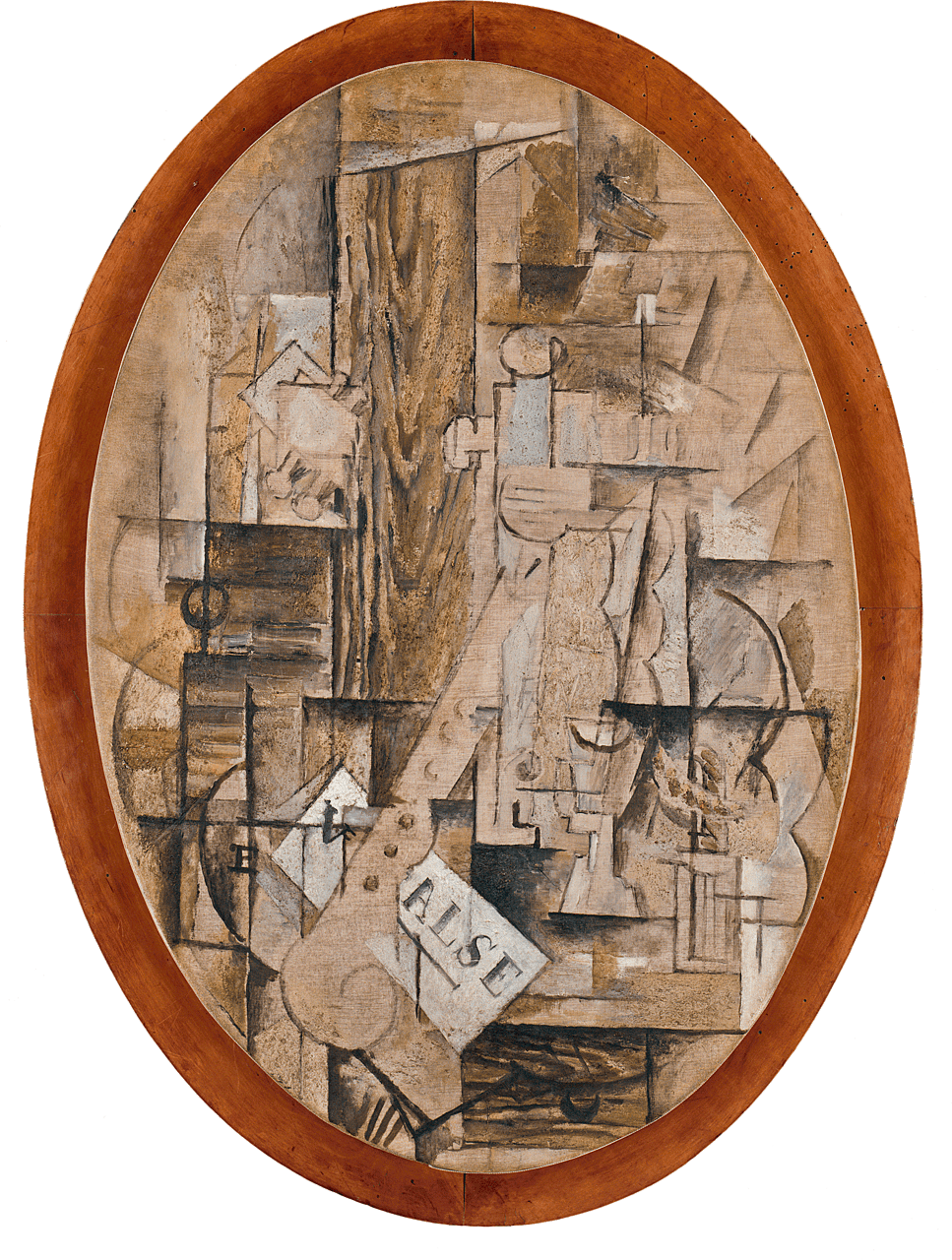

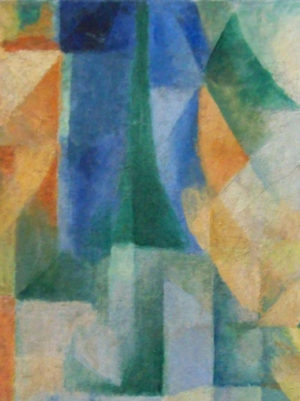

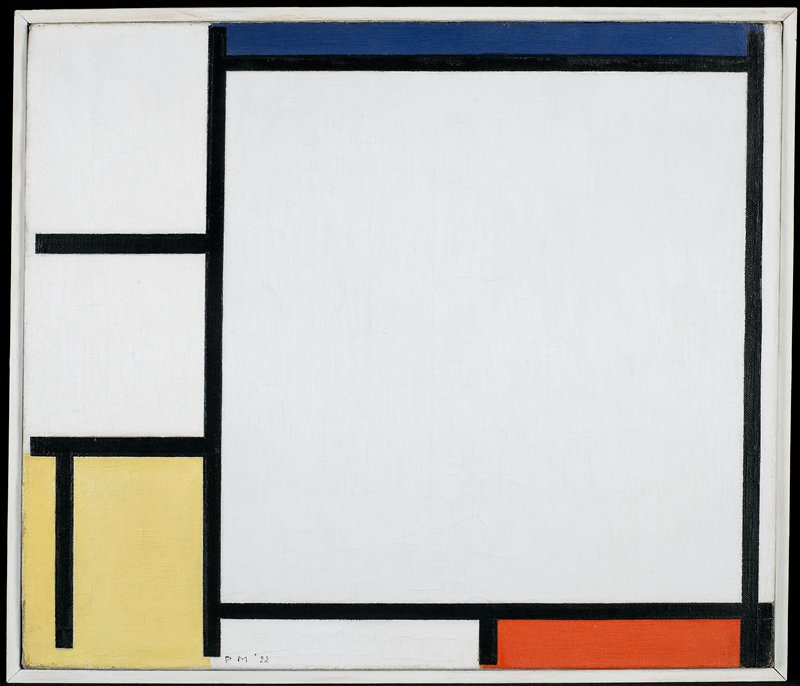

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

Robert Delaunay’s Simultaneous Windows on the City is enigmatic. Where is the city? Where are the windows? At first (and possibly second and third) glance what we see is a fractured pattern of mostly rectangular planes painted in the colors of the spectrum over both a canvas and its wooden frame. If we consider the post-Renaissance Western conception of a painting as being like a window, then we might interpret the painted frame as a window frame and the canvas inside as representing the city, but this does little to help us see a city depicted in the painting.

Cubist composition

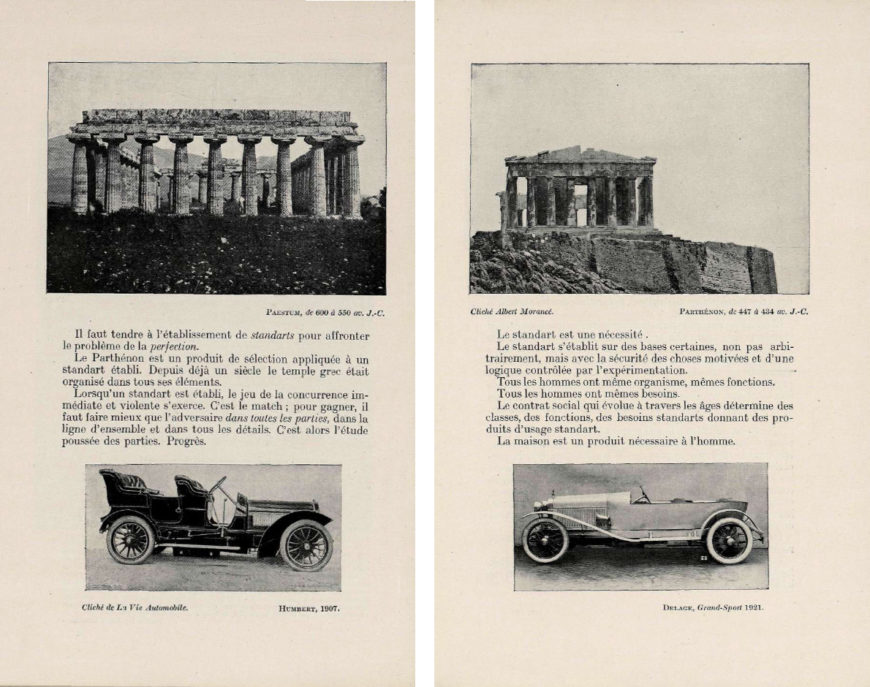

Looking at the painting in Cubist terms is more successful. Delaunay exhibited with the Salon Cubists, and this painting was made as Delaunay’s artistic interests shifted from the Cubists’ analysis of form to an investigation of color and light.

Despite its intense color, Simultaneous Windows on the City remains Cubist in overall composition. Like Braque’s roughly contemporary Cubist composition Man with a Guitar, Delaunay’s painting is a complex grid of dark and light-toned planes and ambiguous forms in which the viewer can find vestigial signs of the subject.

The most recognizable form in Delaunay’s painting is the green Eiffel Tower in the center, rising up from its triangular base to a point toward the top of the canvas. Below the tower are suggestions of rectangular buildings with dark blue windows. Some of these are painted directly on the wooden frame, indicating that it cannot be literally equated with a window’s frame.

The side bars of the frame are, however, darker than the canvas area, and their diagonal edges at the top and bottom create the illusion of a casement window opening into the viewer’s space. The bright yellows and oranges on the canvas convey an impression of warm outdoor light, while the intense blues in the rectangle surrounding the Eiffel Tower suggest sky. The color contrasts also create a sense of spatial depth as the cool blues appear to recede next to the vivid warmth of the yellows and oranges.

An established subject

Delaunay painted many depictions of both the Eiffel Tower and Paris as seen from a window, and this painting is a more abstract version of what was an established subject for him.

Knowledge of his earlier paintings makes it easier to see the representational forms in this one. The orange shapes, for example, are like the curtains in the windows that frame the tower in previous paintings. Here, however, their color also plays a crucial role, suggesting sunlight and creating a chromatic contrast with the blue that intensifies both colors.

Simultanism and Orphism

The use of chromatic contrast is a primary interest in Simultaneous Windows on the City, and became a central concern of Delaunay’s art. He studied the science of vision and color theory, particularly the writings of M. E. Chevreul and Ogden Rood, which had influenced the Neo-Impressionists in the 19th century.

Delaunay used the Neo-Impressionists’ divisionist technique to create a visible mosaic of colored brushstrokes in paintings like Window on the City no. 3, but he soon shifted to using larger planes of color. In 1912 he and his wife Sonia developed an approach to painting light by means of color that they called Simultanism.

The Delaunays were not alone in using the term Simultanism in relation to art. Simultaneity was a popular term with broad significance among avant-garde artists and writers of the time. Generally, it alluded to new concepts of space and time described by early-20th century physicists, such as Einstein, and philosophers, notably Henri Bergson. More specifically, it referred to techniques used by Cubists and Futurists to combine different vantage points into a single “simultaneous” image. Such images were considered a synthesis of memory and perception, and sometimes also a synthesis of many different people’s views.

The Delaunays’ friend, the writer Guillaume Apollinaire, labelled their work “Orphism” or “Orphic Cubism,” and linked it with the work of other artists who were also developing post-cubist styles. Despite Apollinaire’s confusing combination of very different artistic styles and approaches into a single category, the term Orphism has endured. It is sometimes used as a synonym for Simultanism or, more generally, to refer to abstract painting that uses color in a manner comparable to the use of sound and rhythm in music.

The complexity of vision

As we look closely at Simultaneous Windows on the City we experience the complexity of vision. The fractured planes of different colors mimic the way light reflects off glass and how when we look out a window we can often simultaneously see the view outside and reflections of objects inside. Perhaps the curved orange and yellow planes on the right are not a curtain but the reflection of a head and neck with an ear jutting out next to the Eiffel Tower.

The longer you look at the painting the more possible readings of the suggestive forms you are likely to discover. Delaunay’s painting is not only about vision, it is also about painting itself and the way its colored shapes and relationships structure vision. We are led to realize this because the lack of clear representational imagery constantly reminds that we are looking at colors painted on the flat surface of the canvas.

Between abstraction and representation

The Delaunays’ Simultanist paintings explore the potential of color contrasts to create form and depth.

They often hover ambiguously between pure abstraction and representation, particularly the paintings that take the light of celestial objects as their subjects, such as Robert’s Simultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon. A few are clearly non-representational, while others depict specific subjects, ranging from street lamps to dance halls and airplanes.

The modern experience

In adopting the term Simultanism to describe their paintings, the Delaunays combined reference to a famous text on color theory with recent philosophical and scientific explorations of perception and memory. The art they produced reflected this combination in its synthesis of formal concerns and modern subject matter.

Additional resources:

Read Ogden Rood’s Modern Chromatics at the Linda Hall Library Foundation

Robert Delaunay, Simultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Video from The Museum of Modern Art

Russian avant-garde

Russian Neo-Primitivism: Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

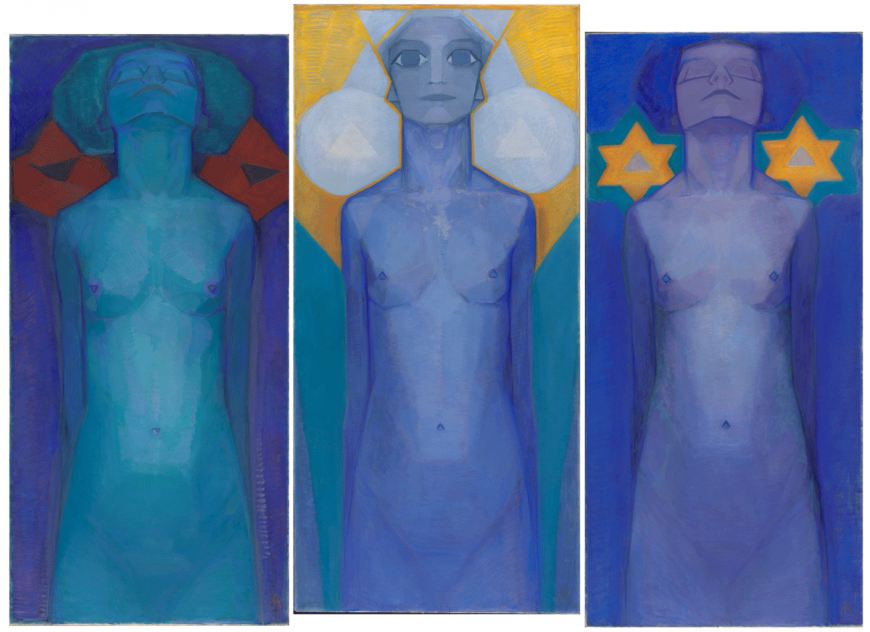

Natalia Goncharova’s Gardening is an example of the contradictions of early-twentieth century Russian modernism. It simultaneously faces outward and inward, forward and backward — outward and forward to engage with some of the most radical trends of European modern art, and inward and backward to reflect on traditional Russian subjects and themes.

Looking forward

In terms of style, Gardening is aggressively modern. With its flat colors and decorative patterning created by the flowers and distant houses, the painting reflects the deliberately simplified style initially developed by the Post-Impressionists in the late nineteenth century. At the same time, the crudely rendered forms of the figures and spatial dislocations suggest contemporaneous painting techniques associated with Fauvism and German Expressionism.

During the first decade of the twentieth century Goncharova and other Russian artists worked hard to assimilate the new styles and attitudes of modern European art. They were able to see many examples of modern art in traveling exhibitions and reproductions in books and magazines. The extensive collections of Ivan Morozov and Sergei Shchukin in Moscow also provided Russian artists with opportunities to view many works by prominent European modernists.

Goncharova was a remarkably prolific and eclectic painter who produced an enormous number of works that show her immersion in contemporary European styles and techniques. Peasants Picking Apples, created a few years after Gardening, depicts a similar subject, but the painting’s forms are flatter and more simplified, now reflecting Goncharova’s assimilation of the formal innovations of early Cubism. This is particularly evident in the simultaneous profile and frontal view of the peasants’ faces and in the hard, angular facets of their bodies.

Peasant life and Russian nationalism

Goncharova’s subjects were at odds with her aggressively international and forward-leaning style. Peasant labor was a popular subject for many Russian modern artists between 1910 and 1913, especially for those associated with Neo-Primitivism, which included Goncharova and her partner Mikhail Larionov, as well as Kasimir Malevich and Aleksandr Shevchenko. Although they were deeply engaged with the developments of European art, Russian modernists were also committed to explicitly Russian themes and subjects — and peasants were a particularly significant subject for them.

Belief in a specifically Russian identity had deep historical roots in Russian culture, which had defined itself since the 18th century in ambivalent relation to Western European culture. Russian modernists maintained this long-standing ambivalence. They embraced many of the ideas and formal innovations of European modernism, but they insisted on interpreting and developing them in distinctively Russian ways.

Peasants who had worked the land for centuries were widely considered to embody the Russian national identity and soul. To assert their difference from Europe, Russian intellectuals described Russian peasants and the land itself as Eastern and Asian or Oriental. Russian peasants were often portrayed as true primitives, uncorrupted by European civilization. Ironically, by embracing the primitive Russian peasant, Russian modern artists were following European precedents, most famously that of Paul Gauguin, who admired and painted the primitive lifestyle of the French peasants in Brittany before he moved to the Pacific Islands.

Embracing Russian folk traditions

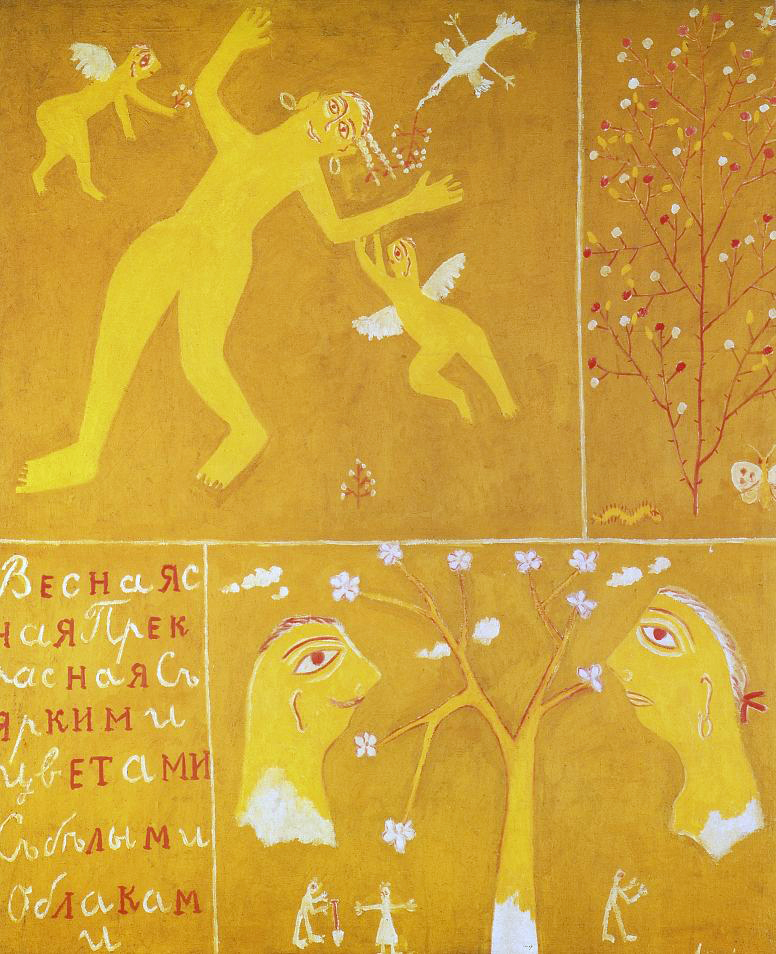

Russian Neo-Primitivist artists did not just depict Russian peasants, they also often modeled their styles on traditional Russian folk art, particularly popular woodcuts called luboks, as well as shop signs, embroidery, hand-made toys, and religious icons. Paintings by Mikhail Larionov display varied styles associated with traditional folk art.

In Spring, instead of depicting peasants performing seasonal labor, Larionov adopted folk art forms to create whimsical panels in bright yellow, red, gold, and white that represent the season of fertility and new growth through symbolic imagery and text. A bird and flying cupids bring flowering branches to a smiling nude woman, a stick figure holds a shovel at the base of one flowering tree, while another flowering tree is flanked by a caterpillar and a butterfly. The style is highly decorative and abstracted in the manner of traditional folk embroidery and painted furniture designs.

Children’s art

Larionov also employed styles associated with children’s art and graffiti, which were considered contemporary manifestations of primitive artistic expression. With its limited palette of vivid primary colors and flat simplified forms, his Soldier on a Horse is reminiscent of crude sign painting and children’s art.

Although it lacks the sophisticated techniques of naturalistic representation, the subject is clearly legible, and the painting effectively conveys the excitement of the rearing horse and the pride of the erect soldier, a nationalistic subject. To emphasize their connection with popular Russian art, Neo-Primitivist artists included the work of children and sign painters alongside their own paintings in the 1913 Target exhibition in Moscow.

Russia’s ancient Scythian roots

Russia’s prehistoric past was also the subject of some Neo-Primitive paintings. Goncharova’s God of Fertility depicts a type of stone funerary sculpture thought to have originated with ancient Scythians (nomadic tribes who roamed Siberia in the first millennium B.C.E.). These mysterious carved stones remained objects of folk superstition and ritual into modern times. Scythian myths and prehistoric pagan rituals were popular subjects for late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century avant-garde Russian music and dance as well. The most famous example is Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, whose primitive rhythms, dissonances and anti-classical choreography caused a scandal at its first performance in Paris in 1913.

In God of Fertility Goncharova again joins a primitive subject to a modern artistic style, using a Cubist technique of faceting to create a non-naturalistic, depthless space in which various symbolic objects associated with fertility float. These include a flower and a horse, the latter referring to the importance of horses in Scythian culture. Abstract geometric forms describe the basic shapes of the ancient sculpture and also suggest that it exists in a space beyond that of the transitory material world.

Promoting Russian modernist primitivism

Neo-Primitivism was an important trend in early Russian modern art, pioneered in large part by Goncharova and Larionov. In addition to producing their own works of modern art, they were organizers of the Jack of Diamonds exhibiting group, which mounted a series of shows of modern European and Russian art in Moscow between 1910 and 1917. The first Jack of Diamonds exhibition showed the French Cubist painters Albert Gleizes and Henri Le Fauconnier alongside Russian artists working in Munich such as Vassily Kandinsky and Alexei von Jawlensky, as well as Russian artists working in Moscow.

In 1912, however, Goncharova and Larionov left the Jack of Diamonds group because they felt it had become too European in its orientation. They mounted The Donkey’s Tail exhibition devoted exclusively to Russian modern art and largely focused on Neo-Primitivism. The artworks nevertheless remained an amalgam of modern and primitive, European and Russian influences. That year, Alexander Schevchenko’s essay “Neo-Primitivism” acknowledged this fundamental contradiction by defining Russian modern art as a hybrid form that had assimilated French avant-garde painting and combined it with the traditional decorative forms of Russian folk art and icons.

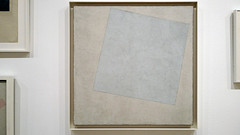

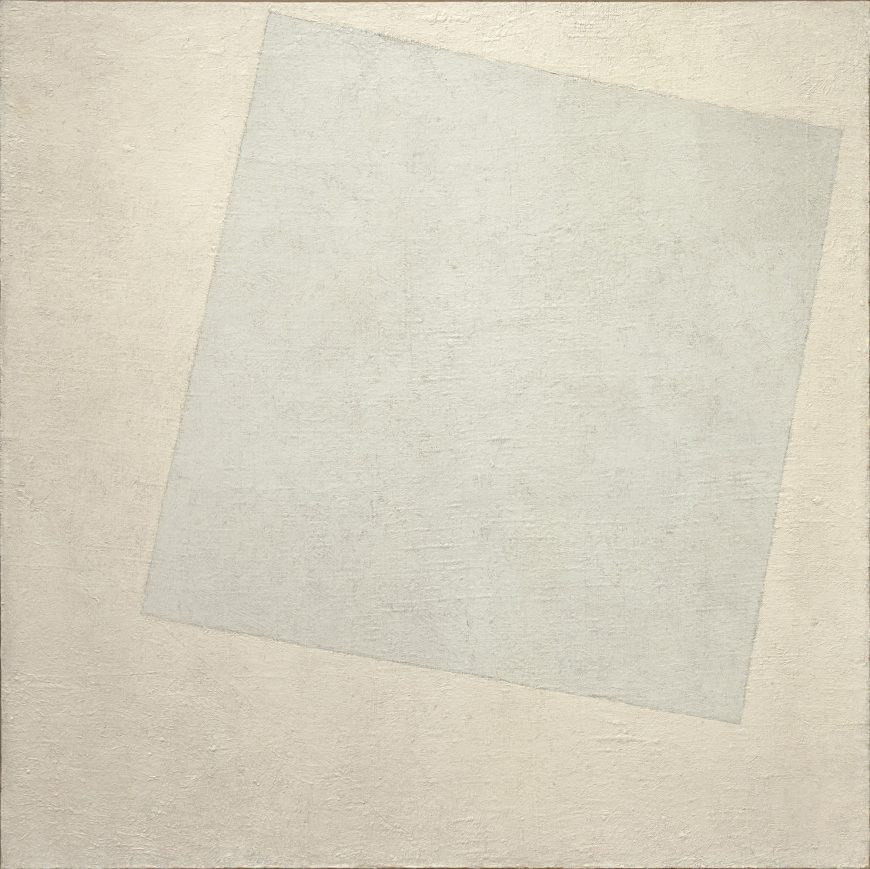

A new world after the Russian Revolution: Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: White on White

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Kasimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918, oil on canvas, 79.4 x 79.4 cm (The Museum of Modern Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

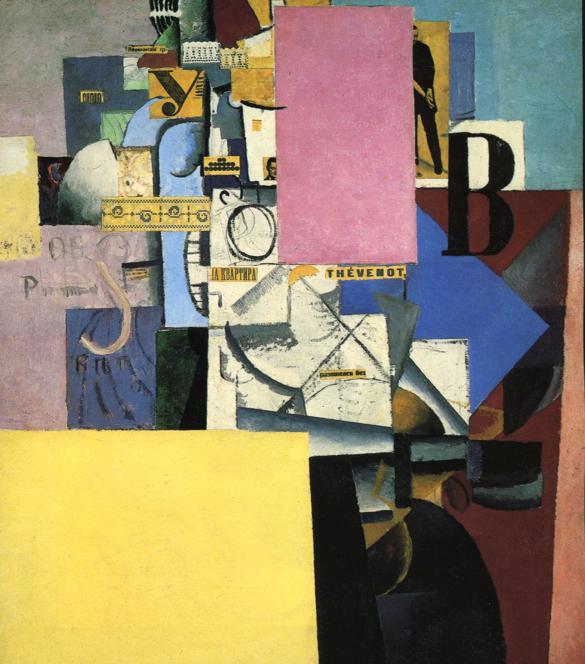

Kasimir Malevich and Cubo-Futurism

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

Kasimir Malevich created Reservist of the First Division (1914) in the first year of World War I. The title refers to a member of the reserve army waiting to be called up for military service, and it had personal significance as Malevich was himself a reservist (although not in the First Division). He was anxious about going to war, but the painting does not convey any obvious emotion or even a clear message. It is a combination of oil paint and collage in a style related to the Synthetic Cubism of Picasso and Braque. At the time Malevich was part of a group of Russian modern artists known as Cubo-Futurists, who used pictorial techniques initially developed by modern artists in Western Europe.

Combining representations

Like Synthetic Cubist paintings, Malevich’s Reservist of the First Division combines different systems of representation. Several objects are depicted using naturalistic techniques — a white cylinder projecting towards the viewer in the middle of the painting and a green cylinder on the left cast shadows and have traditional chiaroscuro shading to indicate their curved shapes. On the right a human ear is clearly depicted. There are also two immediately recognizable schematic objects — a gold cross just to the left of center at the top, and below it half of a black handlebar mustache on a peachy flesh-colored ground; both are symbolic references to a Russian military man.

These identifiable objects and symbols are detached elements in an abstract geometric design of colored shapes, varied textures, and painted lines that includes paper collages with printed words, letters, the number 8, a postage stamp depicting the Czar, and a real thermometer. The collaged words are: opera (at the top), Thursday and tobacconist (in the middle), and (to the left) the name of a traditional academic painter, A. Vasnetzov, who had rejected Malevich’s paintings from exhibition. The words, like the represented forms, refer to things without clearly relating them to the other elements of the painting.

Zaum Realism

Reservist of the First Division uses fragments of objects, shapes, and words to communicate by non-rational means. This was a central technique of Russian Futurist writers that they called zaum, a neologism usually translated as “transrational.” Zaum entailed using non-referential linguistic forms — simple phonemes, letters, and nonsense words — to bypass rational understanding and communicate emotion directly. The Futurists believed that through zaum they were able to access a higher reality that transcended the limitations of rationality and the material world.

Malevich collaborated with the Futurist writers on several projects, the most important of which was the radically innovative opera Victory over the Sun (1913). Like the Futurists, he tried to use the formal elements of painting (line color, shape, composition, etc.) as direct means to communicate feeling independent of representation or obvious reference. He described many of his paintings, including Morning in the Village after Snowstorm (1912-13) and The Knife Grinder (1912-13), as “zaum realism.”

Russian Subjects

Although Malevich explicitly linked these two paintings to zaum’s direct emotional non-rational communication through basic formal units, they are less abstract and easier to decipher than the slightly later work Reservist of the First Division. Figures and space are simplified into geometric shapes and arranged to create repeating abstract patterns. The Knife Grinder depicts a man pumping a sharpening wheel as he works. His foot, hand, and knife appear in multiple positions to convey motion in time. Malevich derived the faceting of space and figure from techniques popular among many well-known Western European Cubists and Futurists whose works were reproduced in art magazines and exhibited in Russia.

The Italian Futurists often used modern representational techniques to depict conspicuously modern subjects. Malevich, by contrast, used an avant-garde formal vocabulary to represent traditional (even self-consciously “primitive”) subjects. Such subjects were popular among Russian avant-garde painters such as Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, who promoted a specifically Russian approach to modernism by embracing Russian subjects and traditional art forms. Morning in the Village after Snowstorm shows Russian peasants carrying buckets and pulling a sled through a snowy village scene. The Knife Grinder uses his foot to pump a simple wheel and pulley mechanism, a marked contrast to the Italian Futurists’ passion for depicting electricity and powerful, sometimes violent, modern machines such as automobiles, trains, and machine guns.

Combining Media and Styles

Malevich combined geometric abstraction, Cubist systems of representation, and collage in an unprecedented manner in Reservist of the First Division and related works such as Woman at a Poster Column (1914) and Composition with Mona Lisa (1914). With these works the zaum techniques of non-rational communication using basic formal units are more fully realized and developed to include recognizable images and objects detached from their usual context.

All three use large flat planes of color as a structuring device. These planes seem to hover in front of the picture plane, creating complex layers of space markedly different from the shallow, fractured pictorial space of most Cubist paintings. The inclusion of photographs and objects, such as the thermometer in Reservist of the First Division and the strips of lace in Woman at a Poster Column, was also an innovative zaum pictorial strategy that foreshadowed the Dada artists’ embrace of the illogical in their strategically disruptive use of collage.

Replacing Conventions

Composition with Mona Lisa combines a collaged reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa with colored planes and suggestions of cylinders and other objects rendered in a Cubist style. The painted Russian text translates as “partial eclipse,” and the collaged newspaper text directly under the Mona Lisa reproduction declares “apartment for rent,” while the text collaged on the painted cube below reads, “in Moscow.” Two red ‘X’s have been painted on the Mona Lisa’s face and chest, and the top of her head is torn off. The work seems to thematize as well as embody the fact that the conventions of naturalistic representation, which had dominated Western art since the Renaissance, have been cancelled out. New replacements are available in Moscow, and Malevich puts himself at the forefront of the avant-garde.

Malevich’s intense engagement with Cubist and Futurist styles exemplified the Russian avant-garde’s adaptation of European modernist techniques to serve their own distinctive artistic aims — most notably the depiction of specifically Russian subjects. With his later collage works, Malevich ventured into new territory, combining abstract planes with representational elements. In the following year he would break away completely from representation and create a new art movement, Suprematism.

Additional resources:

Read more about Reservist of the First Division

Read more about Morning in the Village After a Snowstorm

Charlotte Douglas, Kazimir Malevich (New York: Harry Abrams, 1994).

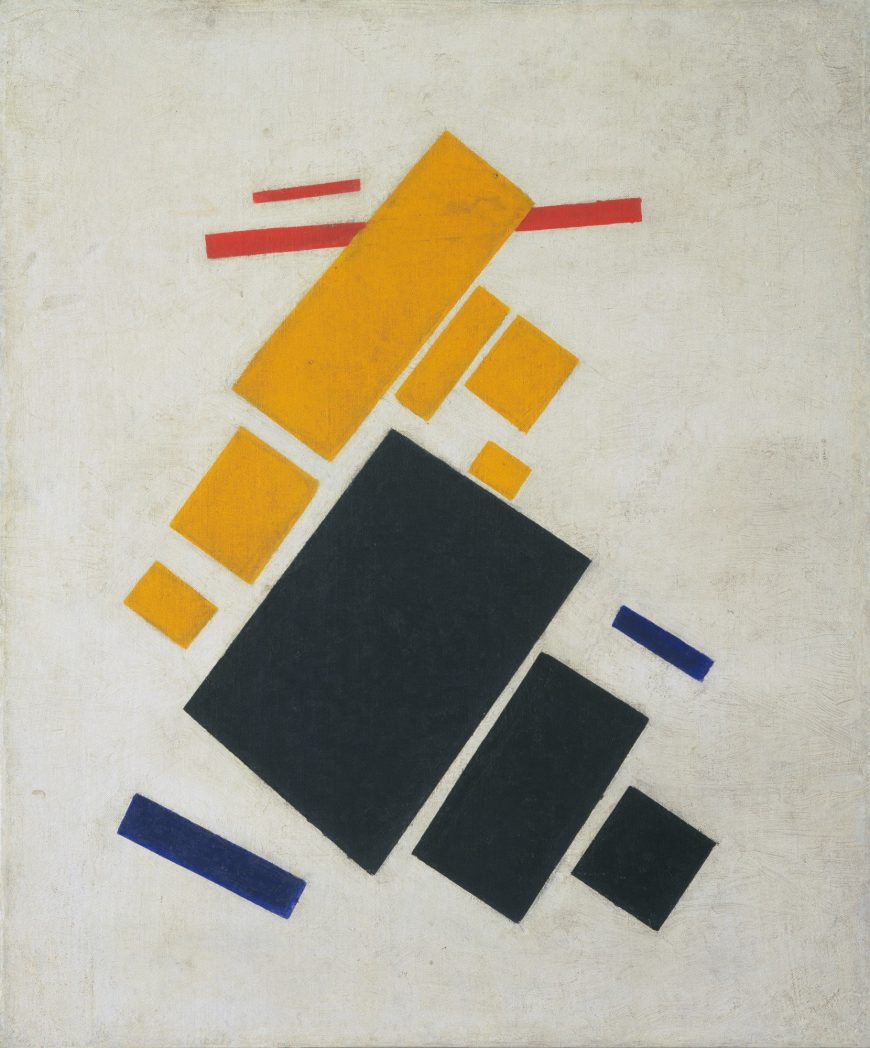

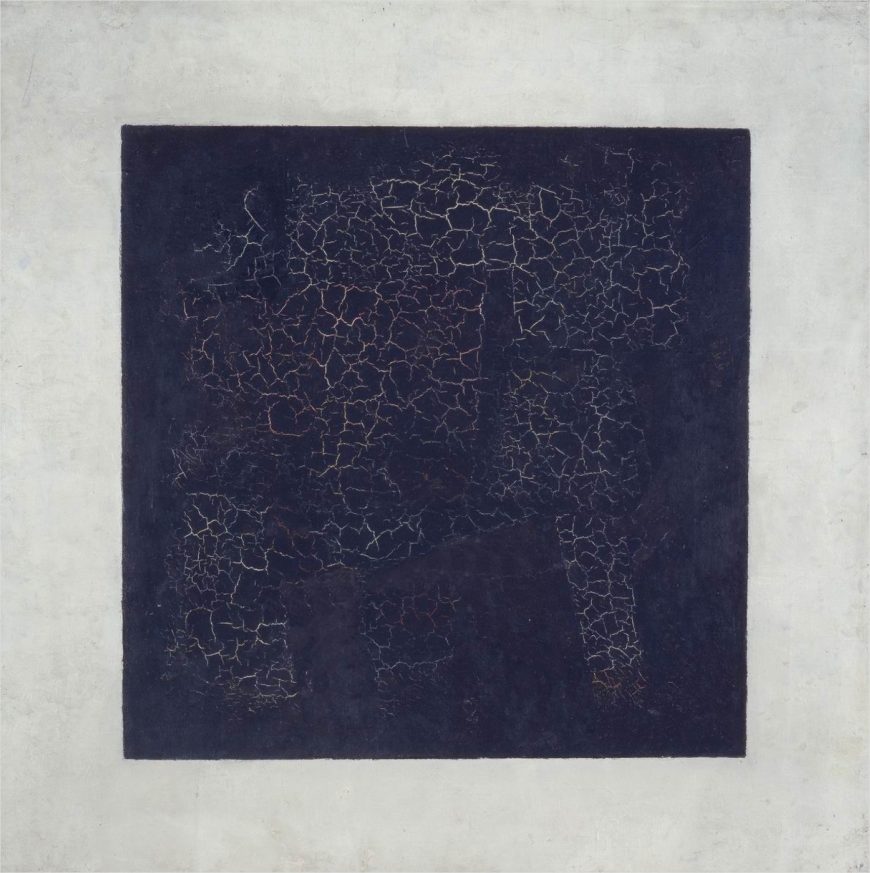

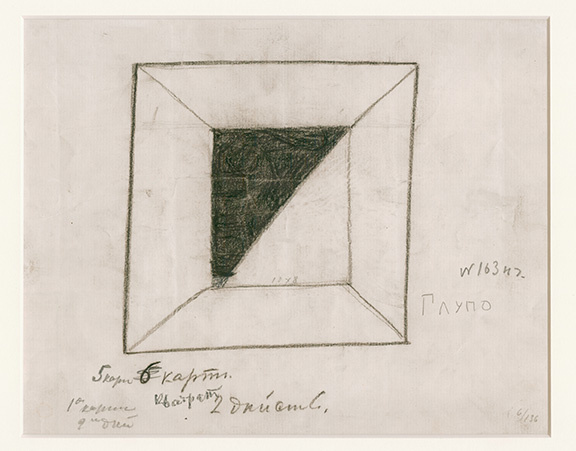

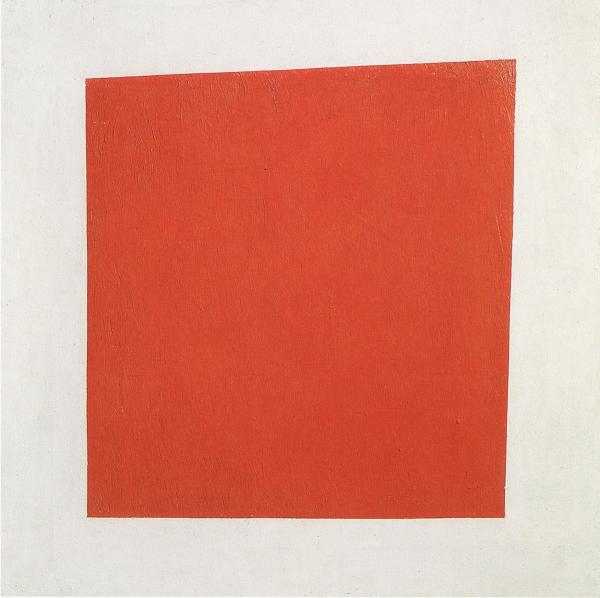

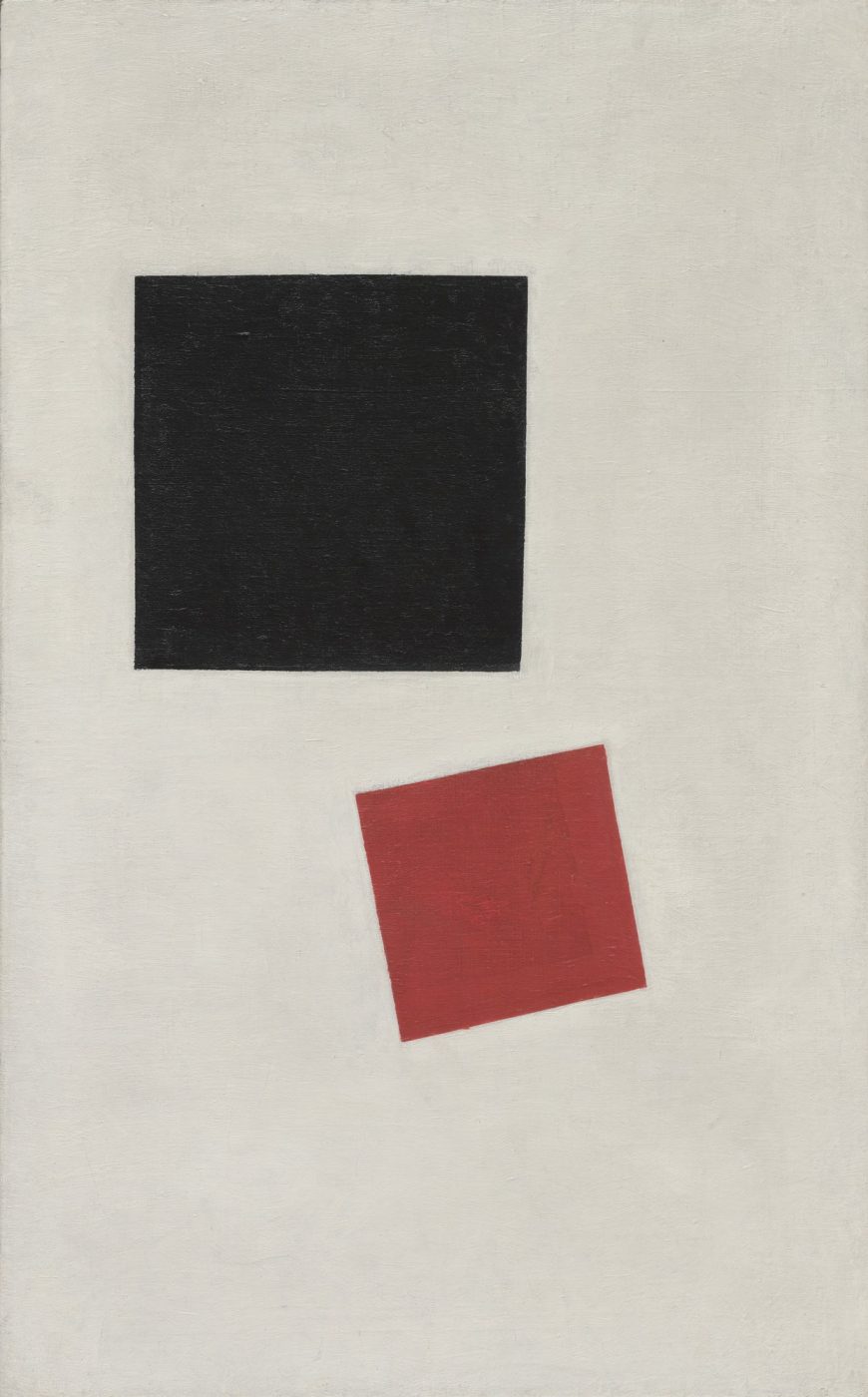

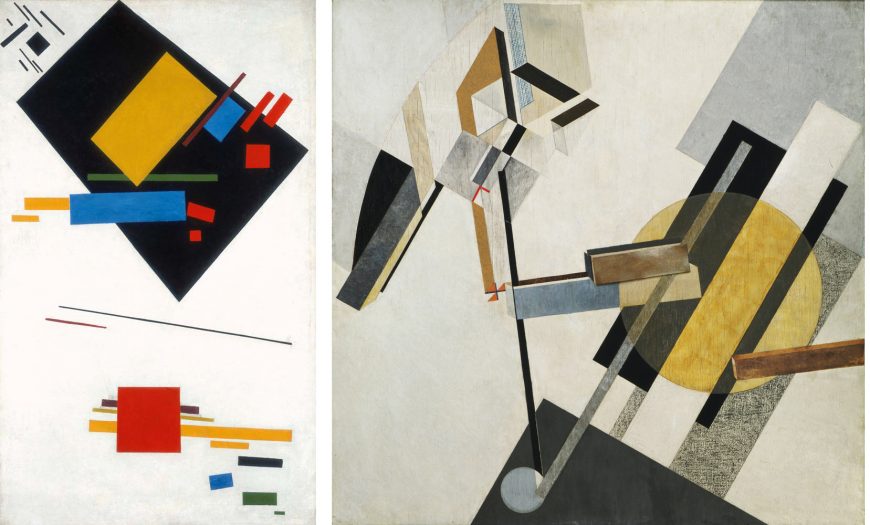

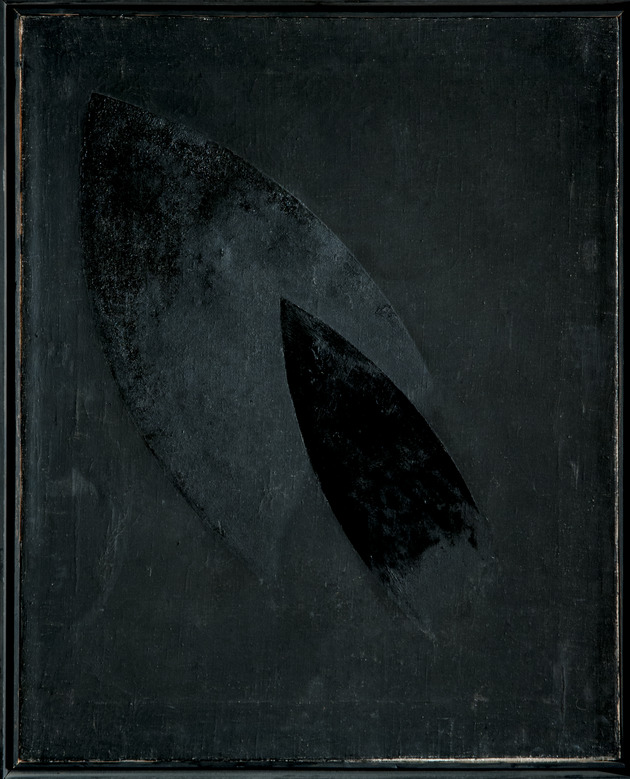

Suprematism, Part I: Kasimir Malevich

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

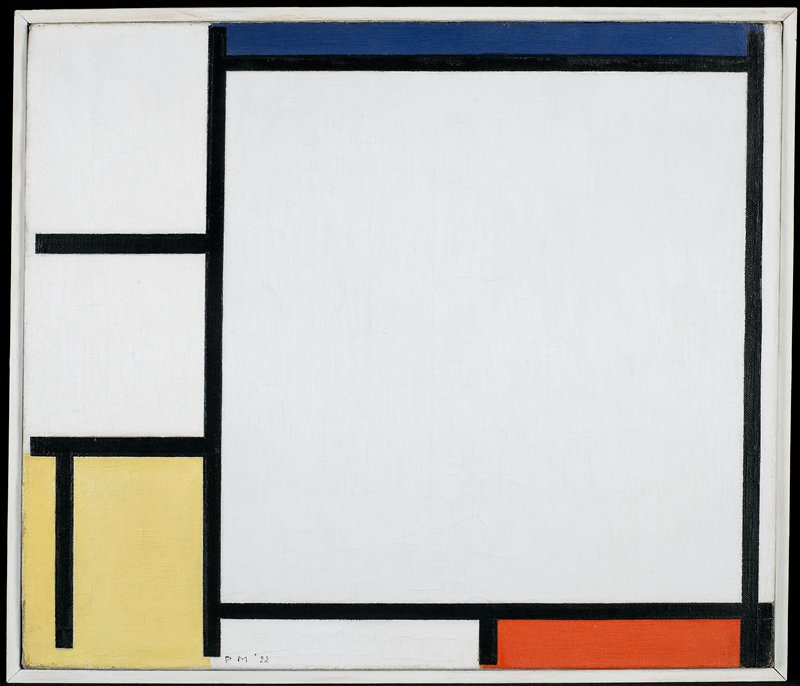

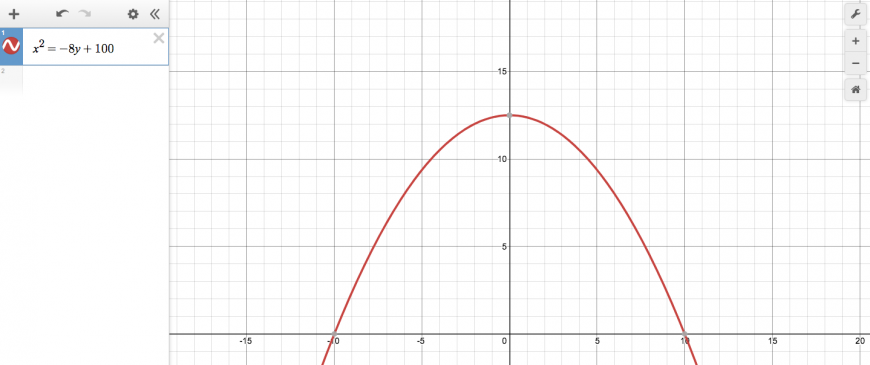

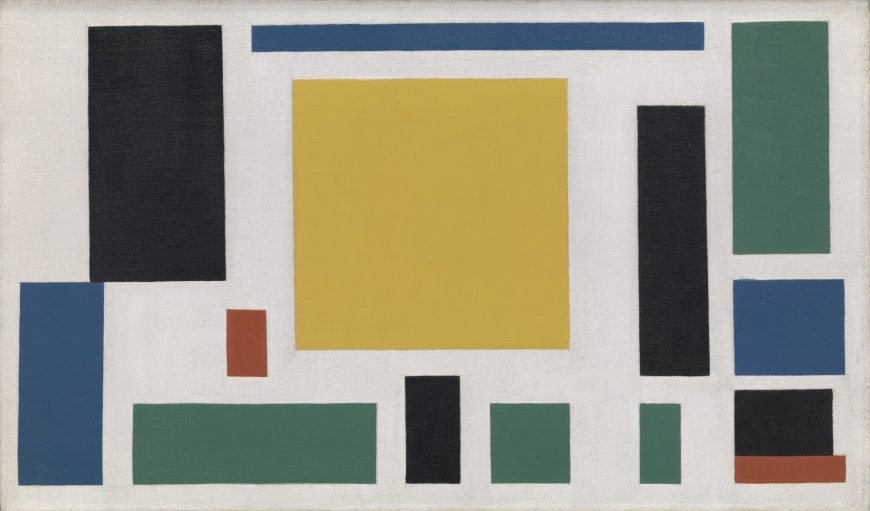

Kasimir Malevich’s Airplane Flying: Suprematist Composition does not depict an airplane. Instead, it was intended to convey the sensation of mechanical flight using thirteen rectangles in black, yellow, red, and blue placed in dynamic relationships on a white ground. Movement is created by the diagonal orientation of the rectangles in relation to the edges of the canvas. Groups of individual colors suggest distinct objects shown at varying distances as they increase or diminish in scale. Ascension is implied by the point of the yellow rectangle centered at the top of the composition, while the bright yellow and red rectangles float above the heavier dark blue and black rectangles.

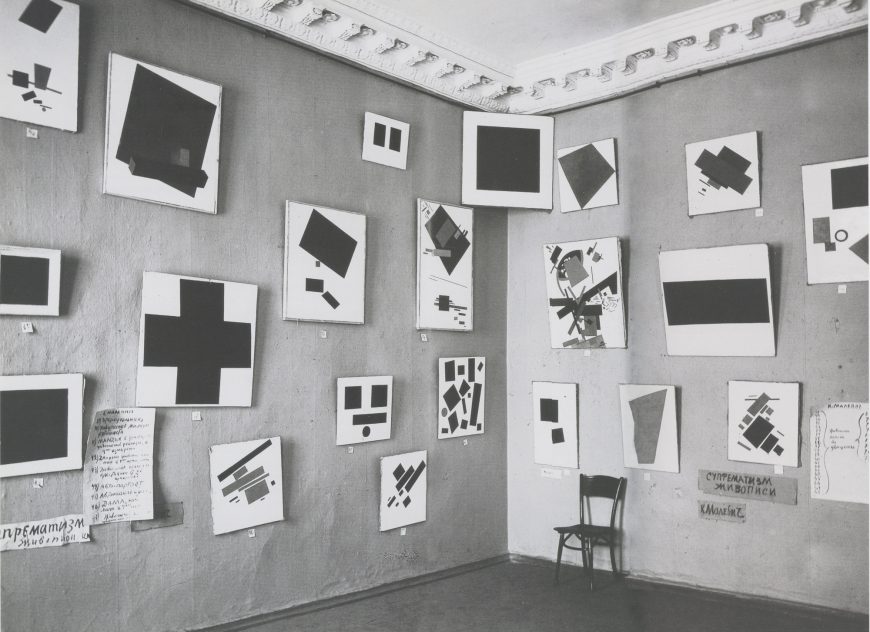

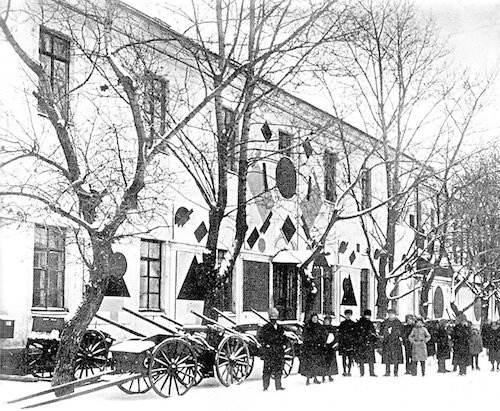

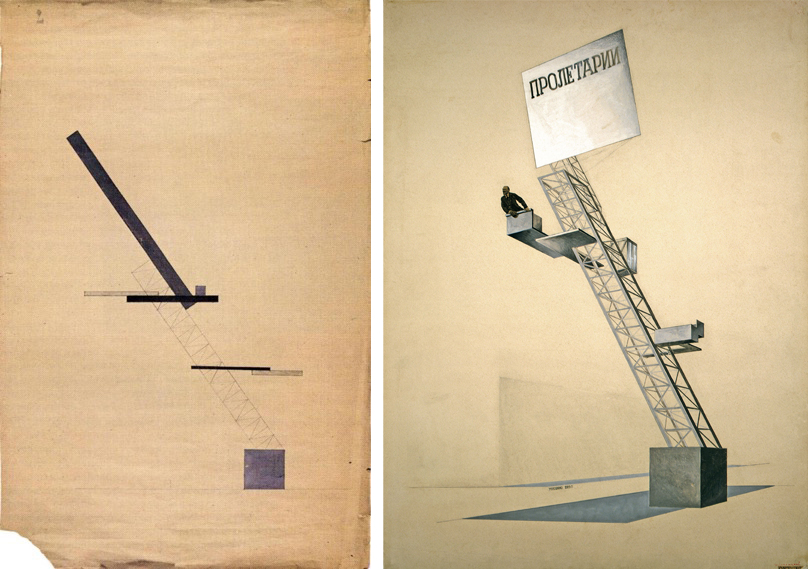

The Last Futurist Exhibition