9.5: Micronesia

- Page ID

- 67092

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Micronesia

This region encompasses, among others, the Caroline, Gilbert, Mariana (including Guam), and Marshall island groups, as well as the country of Nauru.

c. 900 C.E. - present

Navigation Chart, Marshall Islands

by DR. JENNY NEWELL and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Navigation Chart, late 19th century, Marshall Islands, wood, fiber, and shells (American Museum of Natural History). Speakers: Jenny Newell, Steven Zucker and Tina Stege

Master sailors fashioned these maps from sticks and cowrie shells, registering relationships between land and sea.

Wooden sculptures from Nukuoro

At the crossroads of cultures

Nukuoro is a small isolated atoll in the archipelago of the Caroline Islands. It is located in Micronesia, a region in the Western Pacific.

Archaeological excavations demonstrate that Nukuoro has been inhabited since at least the eighth century. Oral tradition corroborates these dates relating that people left the Samoan archipelago in two canoes led by their chief Wawe. The canoes first stopped at Nukufetau in Tuvalu and later arrived on the then uninhabited island of Nukuoro. These new Polynesian settlers brought with them ideas of hierarchy and rank, and aesthetic principles such as the carving of stylized human figures. However the new inhabitants also incorporated Micronesian aspects such as the art of navigation, canoe-building and loom-weaving with banana fiber. Because Nukuoro is geographically situated in Micronesia, but is culturally and linguistically essentially Polynesian, it is called a Polynesian Outlier.

Encounters with Westerners

The Spanish navigator Juan Bautista Monteverde was the first European to sight the atoll on 18 February 1806 when he was on his way from Manila (in the Philippines) to Lima (in South America). The estimated 400 inhabitants of Nukuoro engaged in barter and exchange with Europeans as early as 1830, as can be attested from the presence of Western metal tools. A trading post was only established in 1870. From the 1850s onwards, American Protestant mission teachers who had been posted in the area visited Nukuoro regularly from the Marshall Islands and from the islands Lukunor, Pohnpei, and Kosrae. However, when the American missionary Thomas Gray arrived in Nukuoro in 1902, to baptize a female chief, he found that a large part of the population was already acquainted with Christianity through a Nukuoran woman who had lived on Pohnpei. When Gray returned three years later, he found that the local sacred ground (marae) and the large temple had been replaced by a church. By 1913, many of the pre-Christian traditions including dances, songs, and stories were lost. Most of the wooden images had been taken off the island before 1885 and subsequently lost their function.

Earliest sources

in 1874, the missionary Edward T. Doane made the first mention of carved wooden figures. It is unclear, however, where this experienced missionary got his information from as he never left his ship, the Morning Star, to go ashore. Two German men, Johann Stanislaus Kubary, who visited the island in 1873 and in 1877 while working for the Godeffroy trading company and its museum, and Carl Jeschke, a ship’s captain who first visited the atoll in 1904 and then regularly between 1910 and 1913, give the most detailed information on the Nukuoroan figures.

Wooden sculptures

The first Europeans to collect the Nukuoro sculptures found them coarse and clumsy. It is not known whether the breadfruit tree (Artocarpus altilis) images were carved with local adzes equipped with Tridacna shell blades or with Western metal blade tools (Tridacna is a genus of large saltwater clams). The surfaces were smoothed with pumice which was abundantly available on the beach. All the sculptures, ranging in size from 30 cm to 217 cm, have similar proportions: an ovoid head tapering slightly at the chin and a columnar neck. The eyes and nose are either discretely shown as slits or not at all. The shoulders slope downwards and the chest is indicated by a simple line. Some female figures have rudimentary breasts. Some of the sculptures, be they male, female or of indeterminate sex, have a sketchy indication of hands and feet. The buttocks are always flattened and set on a flexed pair of legs.

Deities

Local deities in Nukuoro resided in animals or were represented in stones, pieces of wood or wooden figurines (tino aitu). Each of the figurines bore the name of a specific male or female deity which was associated with a particular extended family group, a priest and a specific temple. They were placed in temples and decorated with loom-woven bands, fine mats, feathers, paint or headdresses. The tino aitu occupied a central place in an important religious ceremony that took place towards the month of Mataariki, when the Pleiades are visible in the west at dusk. The rituals marked the beginning of the harvesting of two kinds of taro, breadfruit, arrowroot, banana, sugar cane, pandanus and coconuts. During the festivities—which could last several weeks—the harvested fruits and food offerings were brought to the wooden sculptures, male and female dances were performed and women were tattooed. Any weathered and rotten statues were also replaced during the ceremony. For the period of these rituals, the sculptures were considered the resting place of a god or a deified ancestor’s spirit.

Early twentieth-century artists

When the Swiss sculptor and painter Alberto Giacometti made his famous sculpture Hands Holding the Void (Invisible Object) (left) he was inspired by a wooden Nukuoro figure he had seen at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris (now in the collection of the Musée du quai Branly). A fellow artist, Henry Moore, considered the Nukuoro image at the British Museum (image above) to be one of the highlights in the history of sculpture. Both carvings are part of a small group of thirty-seven sculptures from Nukuoro that arrived in Western museum collections from the 1870s onwards. European artists believed that the highly stylized representation of the human in the Nukuoro figures represented the purest form of art—an art that lay at the origins of mankind.

Nukuoro figures today

Today the sight of even a small Nukuoro figure still makes a big impact on visitors. Scattered across museums and private collections in Europe, North America and New Zealand, ten figures were brought together for the first time at the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen, near the Swiss city of Basel. This prompted research in these exquisite sculptures, which has been bundled in a book Nukuoro: Sculptures from Micronesia (2013). Nukuoro figures continue to inspire Nukuoroans and Westerners alike as they are copied, and displayed in places ranging from people’s houses to Pacific themed hotel lobbies.

Additional resources:

Nukuoro figure in the collection of the Barbier-Mueller Museum

Nukuoro Figure in the collection of The British Museum

Animation from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration about how atolls are formed

Christian Kaufmann, & Oliver Wick (eds), Nukuoro. Sculptures from Micronesia (Basel: Fondation Beyeler, Hirmer, 2013)

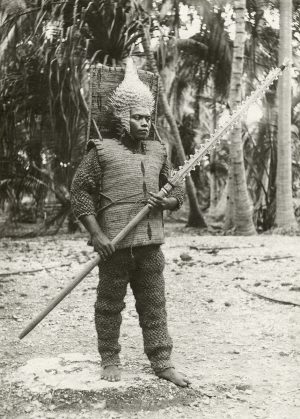

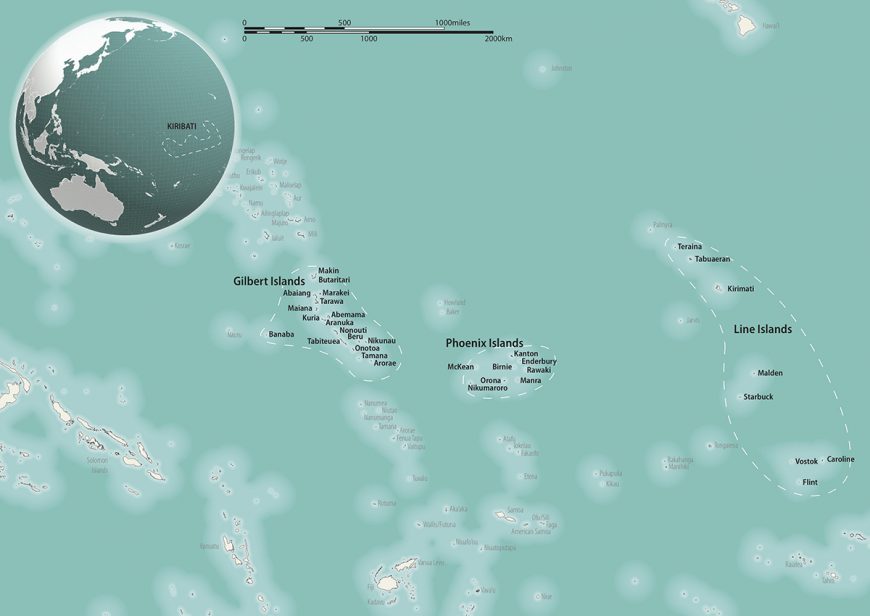

Kiribati armor

What we have, we use

The Republic of Kiribati is a group of thirty-three coral atolls and reefs spread out over 3.5 million square kilometers of the Pacific Ocean. It is located in Micronesia, a region in the Western Pacific. Isolated as an island group, the Islanders use the limited resources they have on hand to produce their material culture.

Historically, the I-Kiribati produced extraordinary objects such as suits of armor made from coconut fiber. The armor provided protection from the dangerous shark’s-teeth-edged swords, spears, and daggers carried by island warriors. Each suit is made up of a set of overalls and sleeves made from coconut fiber, with a coconut fiber cuirass worn over the top. The distinctive cuirasses have high backboards to protect from attack from behind, and were often worn with thick belts made from woven coconut fiber or dried ray skin to protect the vital organs. The cuirasses are usually decorated, either with human hair, feathers or shells.

Warriors sometimes wore hand armor also made from coconut fiber, inlaid with shark’s teeth along the knuckles. The warriors would also wear fearsome-looking helmets made of porcupine fish skin, which dried hard in the sun and provided another layer of protection for the head. These helmets would usually have been worn over a coconut fiber or woven pandanus leaf cap.

It is not known where and when this type of armor was developed in the islands, but it has come to stand as uniquely Kiribati, with its influence also spreading to the nearby islands of Nauru and Tuvalu.

Making the armor

Coconut fiber string, a material still produced and used today, is the main material used for the armor, chosen not just for its availability but also its strength and flexibility. The fibers come from the husk of the coconut, found between the inner shell and the outer skin. These fibers are soaked in the water of the lagoon for two to three months, then rinsed and dried. Several fibers are rolled into small strands, which are then rolled together to create long cords.

Many of the cuirasses feature lozenge-shaped or geometric designs made from human hair; sometimes these diamond shapes are developed to become fish or turtles. Hair is something quite special and precious, but is also easily accessible. The woven diamond motif seen here is most likely women’s hair. Often combined with coconut fiber, hair was also used for binding the shark’s teeth to swords, and is still used today in dance belts.

The process of making the armor would have been associated with a powerful ritual, instilling in the armor the power and strength of the raw materials used to make it. The warriors would also go through a ritual before going into battle.

Wearing the armor

The armor would have been worn in conflict resolution between individuals or groups of people. Generally the fighting would have been related to land claims or retribution. In all contests, the aim was to wound your adversary, not to kill them, as a wound would be adequate retribution. If someone did die during the battle then payment to the wronged party would need to have been made through the gift of land.

Warriors in armor would have carried a shark’s-tooth spear tipped with a stingray barb. They would never have fought alone, but would have been surrounded by a number of people who were not wearing full armor, carrying branched spears, clubs, and small daggers. In cases of inter-village or island warfare, each side would march in three groups, with the main warriors in the center surrounded by their supporting troops. When the two sides met, the overall outcome would depend on the result of individual challenges made by the warriors.

Encounters with westerners

Pedro Fernandes de Queiros was the first European to sight the Gilbert Islands (the main group of islands in what is now the Republic of Kiribati) in 1606. The British explorers John Byron, Thomas Gilbert, and John Marshall all passed through the sixteen atolls without landing between 1764 and 1788. The islands were named the Gilbert Islands by the Russian general Adam Johann von Krusenstern, who also crossed without landing in 1820. The French captain Louis Duperrey then mapped the islands fully in 1824.

There are records of Kiribati armor in European collections as early as 1824 [1], but there are no known descriptions of it in historical records until 1844, when the United States Exploring Expedition published an account of their arrival on Tabiteuea (an atoll in the Gilbert Islands). Whalers and blackbirders from Australia, the United States, and Europe also visited the islands during the 1800s, often settling there for periods and taking home the armor they acquired.

The rapid decline in the production of this type of armor is generally attributed to the influence of missionaries, who first arrived from France in 1888, and the British, who arrived 1892, both of whom introduced new laws and attempted to pacify the islands. I-Kiribati do not commonly make anything that is not needed; a lack of further need for the armor is likely one of the reasons that these objects were offered to tourists, government officials, explorers, whalers, and other visitors, and why so many are now found in museums across the world.

Kiribati armor today

Small decorative shark’s-teeth daggers are still produced for tourists. However, suits of armor are no longer made for use. Today, historic suits of armor can be found in Kiribati on exhibition at Te Umwanibong, the Kiribati Museum and Culture Centre on Tarawa atoll, but it is not known that any others exist in the islands.

In 2016, the Pacific Presences project, based at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge commissioned New Zealand-based artists Chris Charteris, Lizzy Leckie, and Kaetaeta Watson to make a new suit of armor. This armor, named Kautan Rabakau, is now part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Kiribati became an independent nation in 1979, and since then the image of the “warrior” has re-emerged, and can be seen used on clothing and as mascots for sports teams—a symbol of strength and pride. It has also been repurposed by the Mormon faith Moroni High School in Tarawa, who see themselves as fighting both a spiritual and physical war in the modern world.

While the battles that necessitated this armor are over, Kiribati now faces the new challenges of climate change and the effects of westernization on traditional life and culture.

The research for this entry was produced during the European Research Council funded project: ‘Pacific Presences: Oceanic Art and European Museums’, under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) / ERC grant agreement n° [324146]11.

[1] A shark’s-teeth sword was donated to the Diocesan Library in Linkoping, Sweden in 1824, and coconut fiber dungarees were donated to the Whitby Museum in 1834.

Additional resources:

Kiribati armor in the collection of the British Museum

Kiribati armor in the collecton of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

An Ethnographic Analysis of a Kiribati Shark-Toothed Sword

Gerd Koch, The Material Culture of Kiribati (Suva: University of the South Pacific,1986).

Sister Alaima Talu, Kiribati Aspects of History (Suva: University of the South Pacific, 1979).

Chris Charteris and Jeff Smith, Tungaru: the Kiribati Project (Auckland, McCollams Print, 2014).

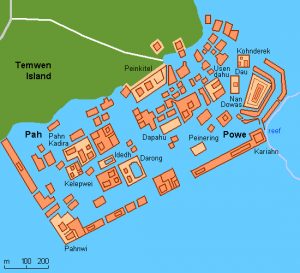

Nan Madol: “In the space between things”

How did they do it?

Sometimes art and architecture calls on us to reimagine what we think was possible in the past, and what ancestors were able to achieve. The abandoned megalithic capital of Nan Madol, located in a lagoon adjacent to the eastern shoreline of the island of Pohnpei in the Federated States of Micronesia in the Pacific Ocean, is a terrific example. [1] Once the political and ceremonial center for the ruling chiefs of the Sau Deleur dynasty (c. 1100–1628), Nan Madol is a complex of close to 100 artificial rectilinear islets spread over 200 acres that are thought to have housed up to 1000 people. Its basalt and coral rock structures were built from the 13th to the 17th century by a population of less than 30,000 people and their total weight is estimated at 750,000 metric tons. Archaeologist Rufino Mauricio pulls these vast quantities into focus for us by explaining that the people of Pohnpei moved an average of 1,850 tons of basalt per year over four centuries—and no one knows quite how they did it. [2]

Immense human power

Nan Madol specialist Mark McCoy has used the chemistry of the stones to link some to their source on the opposite side of the island. [3] The creators of Nan Madol managed to quarry columns of basalt from a site in Sokehs, on the other side of Pohnpei, and transport them more than 25 miles to the submerged coral reefs that are the foundations of Nan Madol. There, they used ropes and levers to stack them in an intersecting formation, making raised platforms, ceremonial sites, dwellings, tombs, and crypts. They used no mortar or concrete, relying solely on the positioning and weight of each basalt column, with a little coral fill, to hold each structure in place.

The human power required to move these materials over such an extended period of time and space is evidence of an impressive display of power by the rulers of Pohnpei as well as ecological and economic systems capable of supporting a busy labor force.

Sacred histories

Sometimes oral histories are able to explain the extraordinary feats of men in ways that present-day science cannot replicate. Oral histories of Nan Madol describe great birds or giants moving the basalt rocks into place, others recall the magic used by the twin sorcerers Olosohpa and Olosihpa to create a place to worship their gods. Beyond these creation narratives, aspects of the oral history of Nan Madol, passed down through many generations, correlate with archaeological evidence. For example, oral histories describe a series of canals cut to allow eels to enter the city from the sea. A well on the island of Idehd is said to have housed a sacred eel who embodied a sea deity, and to whom the innards of specially raised and cooked turtles were fed by priests. Traces of the canal system as well as a large midden (mound) of turtle remains on Idehd are among the archaeological evidence that supports these histories.

While the exact engineering of Nan Madol eludes us, we know that the construction of elevated, artificial islets had commenced by 900 to 1200 C.E., and that around 1200 C.E. the first monumental burial took place when a chief was interred in a stone and coral tomb. This significant ceremonial event was followed by a period of truly megalithic building from 1200 to 1600 C.E.

Madol Pah in the southwest was the administrative center of the complex and Madol Powe in the northeast was its religious and mortuary sector. This area comprises 58 islets, most of which were inhabited by priests. The most elaborate building is Nandauwas, the royal mortuary, which covers an area greater than a football field. Its walls are 25 feet high and just one of its cornerstones is estimated to weigh 50 tons. Elsewhere, log-cabin style walls of stone reached 50 feet in height and are 16 feet thick, and were topped with thatched roofs. All were protected from surging tides by large breakwaters and seawalls.

What’s in a name?

Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggest that certain islets were dedicated to specific activities—Dapahu to food preparation and canoe building, and Peinering (“place of coconut oil preparation”), Sapenlan (“place of the sky”) and Kohnderek (“place for dancing and anointing the dead”) to the activities their names describe. Tombs surrounded by high walls can be found on Peinkitel, Karian and Lemonkou.

Powerful rulers

Nan Madol is simultaneously an engineering marvel, a logistical puzzle, and the product of a sophisticated economy and highly stratified society—all presided over by a dynasty known as the Sau Deleurs. Who were these leaders who inspired (or perhaps coerced) the people of Pohnpei into such a long-term and physically challenging undertaking? Many oral histories describe them, and there are many possible interpretations of these, but most agree that for many centuries Pohnpei was under the rule of a series of chiefs (Sau) descended from Olosohpa, who began as gentle leaders but came to exert extraordinary power over their people before deteriorating into tyrants. Under their rule the people of Pohnpei not only built the Nan Madol structures, but also made tributes and food offerings to the Sau Deleur, including turtles and dogs, which were reserved for their consumption. This period of history is remembered as the “Mwehin Sau Deleur”—the “Time of the Lord of Deleur.”

The dynasty was overthrown by the culture hero Isokelekel, who destroyed the last of the Sau Deleurs in a great battle. Following his victory, Isokelekel divided power into three chieftainships and established a decentralized ruling system called Nahnmwarki which remains in existence today. He took up residence at Nan Madol on the islet of Peikapw. A century later, his successor abandoned the site and established a residence away from Nan Madol. The site gradually lost its association with prestige and its population dwindled, though religious ceremonies continued to be held here from time to time into the late 1800s.

Artifacts found at Nan Madol include stone and shell tools, necklaces, arm rings, “trolling lure” ornaments, drilled porpoise and fruit bat teeth, quartz crystals, lancet and disc-shaped bead necklaces, pottery, remnants of turtle and dog status foods, and large pounders used to process the root of the kava plant (Piper methysticum) into a ceremonial drink. Kava has mild sedative, anesthetic and euphoriant qualities, and its botanical name literally means “intoxicating pepper.” Extensive personal adornments, food, and kava are evidence of Nan Madol’s significance as the ceremonial center of Eastern Micronesia.

The garden of Micronesia

Pohnpei is rich in natural resources and has been called “the garden of Micronesia.” It has fertile soil and heavy rainfall, that promotes the growth of lush vegetation from its coastal mangrove swamps to the rainforests at the apex of its central hills, as well as lagoons. These natural resources would have provided the necessary food for the workers who built the extraordinary complex that is Nan Madol, as well as timber that may have been used to help shift the basalt rocks. It seems unlikely that any foods were cultivated within Nan Madol, and likely no source of freshwater existed within the complex—food and water were brought from the island’s interior.

The basalt columns used to build Nan Madol are almost as extraordinary as the megalithic structures they comprise. Columnar grey basalt is a volcanic rock that breaks naturally into flat-sided rods when it cools. Though it appears quite marvelously to have been shaped by chisels, its predominantly hexagonal or pentagonal columns are due to natural fractures that form while a thick lava flow cools. Rapid cooling results in slender columns (<1 cm in diameter) while slow cooling results in longer and thicker columns. Some of the columns used to build Nan Madol are up to 20 feet long and weigh 80–90 tons. [4]

A space between things

In July 2016, Nan Madol was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The dedicated UNESCO webpage explains that “The huge scale of the edifices, their technical sophistication and the concentration of megalithic structures bear testimony to complex social and religious practices of the island societies of the period.” [5] It also describes how siltation of the waterways that are an integral part of this site is allowing an overgrowth by mangroves. Both the mangroves and the siltation are threatening the structures themselves.

Since Nan Madol was built on a coral foundation, it is sometimes called “the Venice of the Pacific.” Like Venice (which is made up of 117 islands), the islands of Nan Madol are connected by a network of tidal channels and waterways. These are referred to in the name Nan Madol, which means ‘in the space between things’—here, as elsewhere in the Pacific, waterways are described as connectors of people and places rather than barriers. The waterways might be local, like the canals of Nan Madol, or expansive, like the great Pacific Ocean, the largest body of water on Earth.

To get a sense of the extent of this space between things, it is instructive to zoom in on Nan Madol using an online mapping system. Pinpoint Sokehs Pah while you are at it, so you can also see the distance between this quarry and the ancient capital built from its rock supply. Then, frame by frame, zoom out. Marvel at the space that unfolds as you ponder what motivated the Sau Deleur dynasty to build such an expansive, impressive and intimidating structure, and just how they might have achieved this.

Notes:

- On the island of Kosrae is another smaller capital at Leluh with megalithic architecture made from columnar basalt around 1300–1400 C.E.

- Christopher Pala, “Nan Madol: The City Built on Coral Reefs,” Smithsonian.com, November 3, 2009. Nan Madol has inspired many speculative “lost continent” theories as well as songs and popular fiction. More recently it featured as a cultural city-state in the 2016 video game Civilization VI.

- “New Research Sheds More Light on Ancient Pacific Site,” RNZ, October 25, 2016. See also Mark McCoy, “Earliest direct evidence of monument building at the archaeological site of Nan Madol (Pohnpei, Micronesia) identified using 230 Th/U coral dating and geochemical sourcing of megalithic architectural stone” in Quaternary Research, vol. 86, issue 3 (November 2016), pp. 295-303.

- Columnar basalt deposits can be found throughout the world but the best known is probably the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland.

- UNESCO: “Nan Madol: Ceremonial Centre of Eastern Micronesia”

Additional resources:

U.S. National Park Service webpage for Nan Madol

Nan Madol on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Nan Madol information and photos from the International Archaeological Institute

Sketchfab model of a burial monument at Nan Madol by Mark McCoy

3-D models of Nan Madol by William Ayres, University of Oregon

“Centres of Power and Monumental Architecture in Micronesia,” in Art in Oceania (Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 58–61