7.7: Italy in the 16th century- High Renaissance and Mannerism (II)

- Page ID

- 71076

Venice in the 16th century

Painting at its most poetic.

1500 - 1600

Three synagogues in the Venetian Ghetto

by DR. DAVID LANDAU, DR. MARCELLA ANSALDI and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): German Synagogue (founded 1528), the Italian Synagogue (founded 1575), the Canton Synagogue (1532), and the Jewish Museum, Venice, This is an ARCHES video with Dr. David Landau, Dr. Marcella Ansaldi, Director of the Jewish Museum of Venice, and Dr. Steven Zucker

Giorgione

Giorgione, The Tempest

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Giorgione, The Tempest, c. 1505-1508, oil with traces of tempera on canvas, 82 x 73 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

What is so tempting?

A burst of lightning illuminates a countryside engulfed in a thunderstorm. Its sudden flash reveals a curious scene: a fashionably dressed man standing on a riverbank eyeing a nearly nude woman seated on the opposite shore nursing an infant. The figures are alone in an otherwise lush landscape that glows turquoise in the storm’s humid air. Groves of tall trees flank a deep view extending backwards along a central waterway to a rural town on the horizon. The breastfeeding woman gazes outward as if questioning our intrusion upon the secluded rustic scene.

Few paintings, if any, in the history of European art vex art historians as much as Giorgione’s Tempest. Painted in Venice sometime between 1505 and 1508, it has generated a steady flood of conflicting interpretations bent upon discovering its precise meaning. No consensus has been reached that fully explains its ambiguous imagery. Studying Giorgione presents a conundrum since little is securely known about his artworks, patrons, or life (cut short by his death from the plague in 1510)—yet he exerted considerable influence on the subsequent history of Venetian painting. Innovations evident in The Tempest showcase Giorgione’s technical experimentation and increasingly novel subjects that reshaped European easel painting.

A downpour of interpretations

One of the central controversies viewers of The Tempest must face is making sense of its subject matter and meaning. Even sophisticated art connoisseurs in the sixteenth century puzzled over its imagery. The first recorded viewer in 1530 identified its figures but not any overarching narrative or theme. One of Giorgione’s earliest biographers, Giorgio Vasari, lamented in annoyance that he could not understand the meaning of the artist’s public paintings, nor supposedly could other learned viewers around Venice. Inventories likewise only vaguely identify the Tempest’s male figure as a “soldier” or “shepherd,” and the female figure as a “gypsy” or even more generically as a “woman.”

Many commentators, insisting Giorgione intended a preconceived theme in The Tempest, have been lured to resolve such enigmatic details. The painting has generated an enormous modern scholarly literature, with over 100 proposals for its imagery—nearly all of them different. Despite this, most interpretations tend to cluster around four main strategies. The first approach seeks to decode the picture’s iconography (its presumed textual or literary sources) to unveil a hidden symbolic narrative. Stories from mythology, classical history, religion, bucolic poetry, and humanist texts have all been linked to it. A second approach connects its prominent outdoor setting to landscape painting’s emerging popularity within aesthetic tastes and Italian art theory in the early sixteenth century.

Yet a third approach interprets Giorgione’s landscape as a socio-political allegory of the Veneto region. The Tempest, according to these hypotheses, represents a deeply nostalgic vision of Venetian territory as a peaceful Golden Age Arcadia during a period when the Veneto region was in fact under siege from foreign armies during the War of the League of Cambrai (1508–17). For other art historians, the male figure’s multicolored hosiery and fancy jacket correspond to theatrical costumes of Venetian Compagnie della Calza (Confraternities of the Sock), who often staged plays with rustic countryside settings resembling Giorgione’s landscape.

In sharp contrast is a final interpretive approach proposing that Giorgione’s Tempest lacks any primary subject matter or theme whatsoever. Instead, some art historians argue it exists as a capriccio (an imaginary topographical scene) or fantasia (fantasy) whose meaning is intentionally left open. In this line of reasoning, with The Tempest Giorgione invents the Renaissance genre of poesia (pl. poesie). This mode of painting aspires to the highly lyrical and musical qualities of verse, and resembles visual poetry meant to generate multi-layered responses.

Audiences for landscape painting

The Tempest is among the first paintings to be labeled a “landscape” in Western art history. Giorgione thus plays a key role in the rising status of landscape painting during the early sixteenth century in Italy and northern Europe. Particularly in Venice, relatively small cabinet pictures such as The Tempest depicting scenes with prominent outdoor settings were actively sought by a new generation of innovative patrons and collectors.

The first known owner of The Tempest was the wealthy Venetian nobleman and soap merchant Gabriele Vendramin. Displayed alongside antiquities and other works by Giorgione in the Vendramin palace, The Tempest likely expressed its owner’s personal magnificence, cultured taste, and intellectual acumen. Vivid effects of weather and light are signature artistic devices for the artist. For example, his Three Philosophers and so-called Sunset colorfully portray ephemeral lighting conditions that likely captivated original audiences as much as modern viewers. However, the present title of La tempesta (the storm) is a modern invention coined in 1894.

The painting dispenses with fifteenth-century hierarchies dictating figures be given central importance in scale and composition over the landscape. Giorgione empties out the narrative core of the picture. His working method in The Tempest indicates the primary importance he designated for landscape in the overall composition. It is laid down first without any portions left reserved for figures, who are painted last and overtop the finished countryside. This unconventional choice subordinates the usual narrative elements—in this case man, woman, and infant—to the periphery. Instead, virtuoso depiction of land and atmosphere possibly stand as the true subjects of The Tempest—eclipsing any human drama.

Technical innovation

What distinguishes The Tempest from earlier small easel pictures produced in Venice is Giorgione’s exploitation of newly available painting technologies. The medium of oil paint applied to a canvas support was typically reserved for large-scale civic projects in Venice, such as those completed by the workshops of Giovanni Bellini and Vittore Carpaccio. Giorgione’s much smaller scale and format helped introduce works in this medium to private Venetian homes.

More specifically, The Tempest inaugurates the long Venetian tradition of painterly colore (color) as the dominant expressive element in painting, eventually embodied by Giorgione’s colleague Titian. Opposed to the Tuscan tradition of disegno (design) based on rigorous preliminary drawings for finished paintings, technical examinations of The Tempest’s canvas reveal only minimal sketches. Giorgione employed a largely improvisational approach.

In the finished work, deftly blended gradations of color, light, and tonal contrasts create an atmosphere unifying the composition. Pigment analysis reveals another unconventional choice: Giorgione’s use of mineral-based pigments (yellow orpiment and orange realgar) to achieve deep and rich colors. Touches of much drier tempera paint also occur, demonstrating his tendency toward experimentation. This textural variation results in sensuous details of flesh, thick humidity, and foliage sparkling with moisture.

Additionally, numerous pentimenti (original elements painted out in the final version) are evident. These include portions of the trees, several architectural features in the middle ground and background, parts of the male figure, and a nude woman once seated in the left foreground but omitted in the final version. This latter figure, revealed when the painting was first X-rayed in 1939, demonstrates how Giorgione might have originally intended an alternate subject matter but freely adjusted the content as the work progressed.

Modern reception and influence

The English poet Lord Byron rhapsodized about The Tempest in letters and his poem Beppo (1817), as did the Swiss cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt. Its impact is evident for Realist painters such as Edouard Manet, whose Le dèjeuner sur l’herbe (1863) was likely inspired by its pastoral setting. The American collector Isabella Stewart Gardner tried unsuccessfully to acquire “that beautiful plum” in 1896 for her future museum in Boston. [1]

The continual flood of proposals seeking to decode The Tempest tend to reveal more about the erudition of art historians than Giorgione. Nineteenth-century readings of the painting, guided by Romantic notions of creativity as the expression of individual genius, have exerted an enormous yet problematic influence over scholarship on the painting. Many theories remain dubious since they tend to over-intellectualize the artist and his intentions. There is no evidence Giorgione possessed an advanced education or university training. In this way, The Tempest serves as a fascinating barometer of art historical methodologies and trends, as successive generations grapple with its absorbing and notoriously volatile imagery.

Notes:

- Letter from Isabella Stewart Gardner to Bernard Berenson, Oct. 21, 1896, in R. van N. Hadley, ed., The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner, 1887–1924 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1987), p. 69.

Additional Resources:

This work at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice

Read more about technical analysis of Giorgione’s Il Tramonto at the National Gallery of Art, London

Discover Giorgione’s paintings on Google Arts & Culture

Jaynie Anderson, Giorgione: The painter of ‘Poetic Brevity,’ including catalogue raisonné (New York: Flammarion, 1997)

Sylvia Ferino-Pagden and Giovanna Nepi Scirè, eds., Giorgione: Myth and Enigma (Milan: Skira, 2004)

Deborah Howard, “Giorgione’s Tempesta and Titian’s Assunta in the Context of the Cambrai Wars,” Art History 8, no. 3 (Sept., 1985), 271-89

Salvatore Settis, Giorgione’s Tempest: Interpreting the Hidden Subject, trans. Ellen Bianchini (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Giorgione, Three Philosophers

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Giorgione, Three Philosophers, c. 1506 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Giorgione, The Adoration of the Shepherds

by DR. HEATHER HORTON and DR. MARK TROWBRIDGE

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Giorgione, The Adoration of the Shepherds, 1505/1, oil on panel, 90.8 x 110.5 cm (35 3/4 x 43 1/2 in.) (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.)

Titian

Titian, Pastoral Concert

Farewell, peoples and cities. The countryside will offer delightful displays for my eyes.

—Jacopo Sannazaro, Elegies, Book 1, Poem II, line 24

I know that then my verses will appear/ unpolished and dark, but I hope that even so/ they will be praised by the shepherds in these woods./ . . . And that which I sing now the springs and streams will recite along the valleys, murmuring/ with their far-shining crystal waters. / And the trees that I now consecrate here and plant/ whispering will make answer to the wind.

An intimate moment

On a shady hillside overlooking sunny glens and a distant mountain vista sits a fashionably dressed young man with long, dark locks, a full-sleeved red and black garment, and bi-colored stockings. As he plays his lute, he turns attentively to his companion, a young man with unruly hair and bare feet wearing a simple garment of coarse, brown fabric. Though their faces are in shadow, the intimacy of this moment is palpable. The two lean toward each other, their heads almost touching. The lute-player gazes toward his companion who looks down, listening to the music that resonates in the air between them. They are the center of the composition, oblivious to all else around them.

But they are not alone. Seated close by and forming part of their intimate group is a nude woman holding a wooden flute, her back turned toward the viewer. To the far left stands another nude woman. This one turns away from the group in an elegant contrapposto as she prepares to pour water into a stone well, perhaps fed by the sparkling stream visible in the middle distance, just behind her to the right. Bright, impasto dabs of white paint describe both the small waterfall created by this stream and the reflections on her glass pitcher.

The Pastoral Concert (also known by its French titles, Fête champêtre or Concert Champetre) has long been recognized as a masterpiece of Venetian Renaissance painting; it has also sparked much debate regarding both its authorship and its subject matter. Often attributed to Giorgione, most scholars now favor an attribution to Titian. This fluctuation of attribution is not surprising given Giorgione’s influence on the young Titian, who worked closely with Giorgione early in his career and even completed Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus upon the latter’s untimely death in 1510.

Giorgione laid the groundwork for Titian both in terms of subject matter and technical innovations. Giorgione was the first Venetian to move away from the highly polished application of oil glazes of his teacher, Giovanni Bellini (see the image below). Giorgione, and Titian after him, embraced the tactile potential of oil painting, applying it with varied densities, at times allowing the weave of the canvas to show through and at others building up the surface with thick impasto.

The rougher texture created by this technique endows the forms in the Pastoral Concert (see the nude at the left for example) with a certain haziness or sfumato which has the effect of softening forms and thus effectively conveying both the tactile softness of the nudes’ flesh and the ephemeral, soft light of late afternoon.

Debates about the subject matter

The debates about the painting’s authorship, however, pale in comparison to the debates about its subject matter. Who are these figures? Why are the men clothed and the women nude? Why do the young men not acknowledge their female counterparts, despite their proximity and their nudity? What circumstances brings them together in this manner? These questions have puzzled art historians for centuries and have resulted in many attempts to secure specific identities for the figures. These attempts consistently disappoint and serve ultimately to highlight the painting’s ambiguities and its resistance to a single fixed interpretation. The most successful interpretations are not those that attempt to identify a particular narrative or specific characters, but those that see the painting as the visual equivalent of a pastoral poem.

Painted poetry

Pastoral poetry (which originated with the Idylls of the ancient Greek poet Theocritus) extols the rustic world of the simple shepherd. It celebrates the physical, sensory beauty of the natural world—it speaks of shady forests, gurgling brooks, lowing herds, and gentle breezes. Musical contests between shepherds are a common motif in pastoral poetry, which is often tinged with melancholy as the contestants sing of lost loves and deceased comrades. The contestants frequently call upon the Muses for inspiration and, when blessed by them, create music of such power and beauty that even the woodland nymphs emerge to listen.

Like so many aspects of ancient culture, pastoral poetry also witnessed a revival during the Renaissance as poets vied to emulate their ancient Greek and Roman predecessors. A key figure in this revival was the poet Jacopo Sannazaro (quoted at the top of the page), whose popular poem Arcadia was published in Venice in the first decade of the sixteenth century. Its narrator is a poet from the city who sets aside his lofty aspirations of writing heroic epics and achieving success among cultured city dwellers in order to enjoy the purity and simplicity of the shepherds’ rural existence. He listens to their songs of love and loss, and is inspired to create his own pastoral poetry. Titian’s painting alludes to this hierarchy of poetic genres by juxtaposing the lute—a sophisticated instrument capable of producing complex harmonies, with the primitive pipe—the shepherd’s favored instrument.

Rather than illustrate a particular scene from a pastoral poem, Titian visualizes the mood and motifs of this genre. As in Sannazaro’s Arcadia, the lute-player is a cultured city dweller, perhaps even a member of the Compagni delle Calze (the Companions of the Stockings)—a fraternity of wealthy Venetian youth known for their fashionable attire and for organizing elaborate entertainment (including music and poetry) for aristocratic weddings. Here he has retreated beyond the city visible in the background to the idyllic world of the pastoral poet.

In this imaginary world, each woodland locale, each stream and cave has its own spirit, or nymph. Perhaps the women are the nymphs who embody the spirit of the place, or the muses who inspire the poet, or personifications of Poetry and Music. In a north Italian set of Tarocchi (Tarot) cards, the personification of music (above right) holds a musical pipe, as does the personification of poetry (above left). The latter, notably, also pours water from a pitcher, presumably from the fountain into the stream in front of her. This fountain represents the waters of inspiration that originate on Mount Parnassus, the realm of Apollo, god of music and poetry, and his nine Muses. The women may not be visible to the young men, but their presence is felt in the beauty of the poet’s song.

A Venetian genre

The Pastoral Concert exemplifies a distinctly Venetian invention focused on the idyllic landscape populated by gods and goddess, nymphs and satyrs, shepherds and peasants. Introduced by Giorgione and developed in the works of Titian and other Venetian artists, this genre became one of the most important artistic contributions of Renaissance Venice—its impact lasting far into the nineteenth century. In its conception, it reflects the dictum “ut picture poesis” (as is poetry so is painting)—a central principle in Renaissance art theory, upheld by artists as evidence of the intellectual status of their art. The comparison with poetry placed emphasis not on painting’s manual production, but on the conceptual activity of the artist’s mind. The creation of the visual equivalent of poetry—in which the artist draws on a variety of sources but ultimately creates something original—was one of the reasons Titian attained international fame later in his career. His poesie (as he called them) were coveted by patrons near and far, including the king of Spain.

Such paintings were produced for the private collections of discerning and educated patrons who understood the evocative, poetic subject matter. The Pastoral Concert was familiar enough in theme to be identified with a particular poetic genre, but elusive enough in details to invite contemplation and conversation. It thus provided a form of recreation that served as a visual and mental retreat for the patron—much like the one experienced by the painting’s fashionable lute player. By looking at the painting and reflecting on the poetry it called to mind, the patron could—at least momentarily—escape to the countryside to enjoy the sights and sounds of the shepherd’s world.

Additional resources:

Bellini, Giorgione, Titian and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting: Allegories and Mythologies

Robert C. Cafritz, Lawrence Gowing, and David Rosand, Places of Delight: The Pastoral Landscape (Washington, D.C.: Phillips Collection, 1988).

Patricia Egan, “Poesia and the Fete Champêtre,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 41, no. 4 (Dec., 1959), pp. 303-313.

Peter Humfrey, Painting in Renaissance Venice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

Paul Joannides, Titian to 1518: The Assumption of Genius (Yale, 2001).

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Bellini, Giorgione, and Titian and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting (2006).

Titian, Noli me Tangere

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Titian, Noli me Tangere, c. 1514, oil on canvas, 110.5 x 91.9 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Titian, Assumption of the Virgin

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Titian, Assumption of the Virgin, c. 1516-18, oil on wood, 22′ 6″ x 11′ 10″ (Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice)

Titian, Madonna of the Pesaro Family

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Titian, Madonna of the Pesaro Family, 1519-26, oil on canvas, 16′ x 9′ (Santa Maria Gloriosa die Frari, Venice)

Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1523-24, oil on canvas now atop board, 69-1/2 x 75″ (National Gallery, London)

This is part of a mythological cycle painted by Titian and Giovanni Bellini and commissioned by Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara that includes The Feast of the Gods and The Bacchanal of the Andrians. It originally hung in the studiolo or Camerini d’Alabastro (Alabaster Chamber) of the Duke’s Ferranese castle.

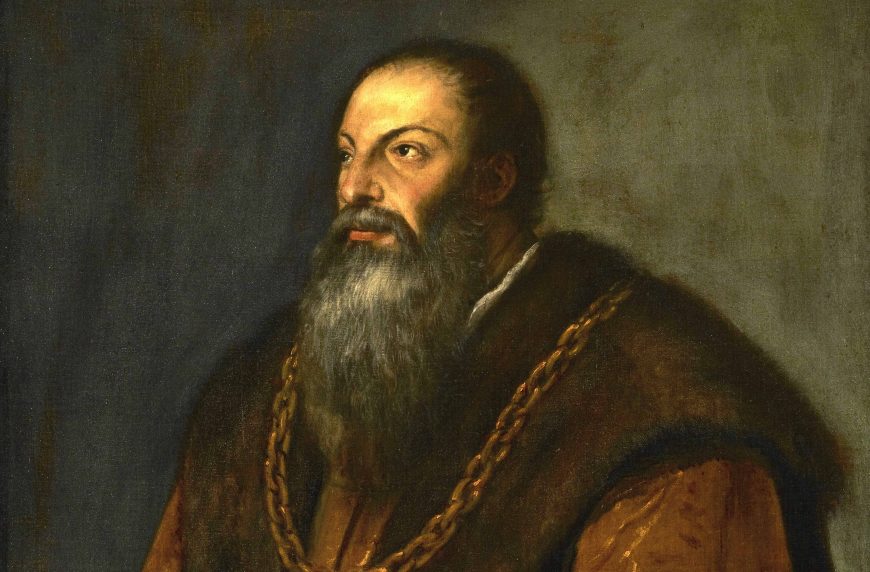

Titian, two portraits of Pietro Aretino

Titian was one of the most celebrated portraitists of the sixteenth century. He enjoyed a high degree of international fame which brought him portrait commissions from the most prestigious families and powerful rulers of Europe. Giorgio Vasari, his contemporary and the renowned author of biographies of Italian artists, wrote that “there is hardly any nobleman of repute, nor prince, nor great lady, who has not been portrayed by Titian.” Titian gave a new twist to portraiture. His portraits have a spark—something special and distinctive. A movement of the hand, a detail in the clothes, or a light in the eyes subtly discloses the inner layers of the sitter’s soul in a way never done before. Titian also had a talent for combining a convincing likeness with a certain amount of flattery.

A lasting friendship

Pietro Aretino was a Tuscan writer, critic, and satirical poet, as well as an international publicist, an art agent, and a collector. He liked to call himself the “scourge of princes.” After some traveling he established himself in Venice where he met Titian, with whom he started a deep friendship that lasted for 30 years.

Aretino was known for his brash style, brilliant wit, bold impudence, and licentiousness. He was a controversial character, but through his charm and persuasiveness he managed to enjoy prominent international friends and patrons throughout his life. Titian’s rapid ascent was also due to the help of Aretino, who assiduously promoted his work as his agent and publicist. Aretino introduced Titian to the nobles of Europe, and in return he acquired a reputation as an arbiter of taste and was admired for being close to such a celebrated artist. Titian is mentioned in many of Aretino’s letters, while Aretino was painted by Titian on a few occasions, two of which are discussed in this essay.

Portrait of Pietro Aretino in the Frick Collection, New York

In this portrait, Aretino occupies the entire canvas with his large, imposing presence. The neutral background allows the sitter to forcefully stand out, while the limited palette vibrates with touches of light on the sleeves and the wriggling golden chain infuses the composition with a touch of life.

With confident and visible brushstrokes, Titian presents his friend in a bust length, three-quarter view. His body and face are turned in the same direction, suggesting assertiveness and determination. His face, in fully illuminated against the shadowy background, becomes the focus of the composition. Through his composition, Titian highlights the centrality of Aretino’s bold and brazen intelligence.

Aretino was the son of a cobbler and was making a living as a writer, but Titian has portrayed him wearing patrician clothing. Aretino’s fur coat displays voluminous sleeves of precious fabric, gloves, and a golden chain, a gift from one of his powerful friends. Aretino’s strong-willed face and bulky chest lends the portrait a degree of conventionality which is contradicted by the roughly-sketched gloved hand that is casually holding his pelisse closed.

Portrait of Pietro Aretino in the Palazzo Pitti, Florence

Like the portrait in the Frick Collection, the sitter’s massive body takes up the whole canvas here. Rough brushstrokes give the painting an unfinished, pulsating effect. The source of illumination coming from the left creates a gleam on the velvet of the coat, depicted in a variety of pinkish-red shades, while part of Aretino’s face and the background are left in shadow. The thinning hair and the disheveled beard are the same as those depicted eight years before, but Aretino’s face appears more deeply creased and expresses a new intensity that was well known to his contemporaries.

As in the previous portrait, Aretino wears the characteristic accessories of the upper classes, including gloves and a heavy golden chain (probably a gift of Francis I, king of France), but here the view of the body is frontal, while his head is in a three-quarter view. With this twist, Titian freezes a moment in time in the life of the writer. The movement, the flickering light, and the sharply focused eyes charge the image with a psychological power. The Venetian artist again communicates his friend’s provocative intelligence and self-assertiveness.

An unsuccessful gift

Aretino sent his portrait to Cosimo I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, in a failed attempt to obtain patronage for himself and Titian. It is possible that the painting was not appreciated, at least initially, as it was a far cry from the taste of the Florentine court, whose favorite portraitist at the time was Bronzino. Bronzino’s sitters are characterized by impassive faces, their bodies outlined by crisp contours and presented in static positions amidst a timeless, almost crystalline atmosphere. Bronzino’s approach diverged fundamentally from Titian’s passionate, quick hand and his preference for color over line.

Aretino was aware of this and, maybe jokingly, in the letter accompanying the portrait wrote: “to be sure, it breathes, its pulse beats, and its spirit moves just as I am in life. And if I had paid more scudi, the materials would indeed have become glowing, soft, or stiff like silk and brocade.”

We don’t know what Titian thought about these words, but we do know that Aretino loved the portrait, referring to it as “an awesome marvel” and as a “continuous mirror of my very self.”

Bucking tradition together

These two portraits tell us about the long friendship between the celebrated Venetian painter and Aretino, one of the most insolent writers of his times. Together, they also express Titian’s talent for rendering human psychology through dense strokes of color.

Additional Resources:

Portrait of Pietro Aretino in the Frick Collection

Portrait of Pietro Aretino from the Palazzo Pitti (at The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Cecil Gould, Grove Art Essentials: Titian (Oxford: Oxford University Press Ink, 2016)

Sheila Hale, Titian His Life (New York: Harper Collins, 2012)

Pietro Aretino: Lettere (Paris, 1609); rev., abridged as Lettere sull’arte, (Milan, 1956–7)

Luba Freedman, Titian’s Portraits Through Aretino’s Lens (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995)

Paul Larivaille, Pietro Aretino (Rome: Salerno Editrice, 1997)

Francesco Mozzetti: Ritratto di Pietro Aretino (Modena: Franco Cosimo Panini 1996)

David Rosand, Painting in Sixteenth-Century Venice: Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto (Cambridge University Press, 1997)

Titian, Venus of Urbino

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538, oil on canvas, 119.20 x 165.50 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence); speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

A highly naturalistic, visual seduction

Who is she? Art historians cannot agree. Numerous identities are proposed for this nude woman seductively reclining in bed as she stares outward from an elegant bedroom. Interpretations of the figure in Titian’s oil painting on canvas, now referred to as the Venus of Urbino, range from the divine to the vulgar. She might be the goddess Venus, a young bride, or an idealized female beauty. Others see her as a courtesan or mistress. Still, she might be intended simply as a generic image of a sexy nude woman. In reality, Titian’s picture likely blends many of these rather limited identities available for women at the time, which tend to overlap within the visual culture of sixteenth-century Italy.

From the 1530s onward, Titian worked for increasingly prestigious clients that included popes, kings, the Emperor Charles V, and rulers of northern Italian court cities. Many of the hallmarks distinguishing Titian as the preeminent painter active in sixteenth-century Italy are evident in the Venus of Urbino. His expressive brushwork, dynamic composition, and brilliant coloring produce an image of pronounced sensuality. The effect is a highly naturalistic, visual seduction—in theme and technical execution—that endures as an influential prototype for depictions of the female nude in European art. Additionally, the Venus of Urbino affords rich insight into the complex social practices intertwining marriage, sexuality, and female beauty in Renaissance Italy.

Painterly seduction

An innuendo of sexual arousal pervades the picture, which Titian emphasizes through several formal devices. The woman’s curvaceous physique is set against a matrix of rectilinear forms: bed, wall partition, window, column, chest, wall hangings, and gridded pavement. Their rigid lines contrast with her body, rendered in fluid brushstrokes that blur at the edges. Titian’s virtuosity with the technique of oil on canvas is evident in her flesh, modeled through subtle gradations in tone and color overlaid with translucent glazes. This simulates ivory skin of exceptional suppleness that flushes pink at her cheeks, hands, knees, and feet.

Set against pearly sheets, her bed cushions are rendered in crimson as if also signaling her passion and inflamed desire, presumably from the entrance of her lover for whom the viewer acts as surrogate. Sadly, much of the original impasto is lost, which once enhanced the tactile qualities of fabric and flesh. The brightly-lit figure and bed project into the foreground and tilt toward the picture plane in slightly foreshortened perspective, enhancing the sense of invitation to viewers.

Intimate viewing

No indication of the subject, meaning, or use of Titian’s Venus of Urbino is given when it is first mentioned in a 1538 letter written by its patron, Guidobaldo II della Rovere, duke of Urbino. He merely refers to it as “the nude woman” (“la donna nuda”). Its present title stems from Titian’s early biographer, Giorgio Vasari, who describes the picture in the duke’s guardaroba (wardrobe suite) at his palace in Pesaro as: “a young recumbent Venus with flowers and certain fine draperies about her, very beautiful and well finished.”[1]

The installation of the Venus of Urbino in the ducal guardaroba meant it was intended for private viewing. It hung alongside other highly sexualized paintings showcasing nude female bodies arranged in classicizing poses: Titian’s Penitent Magdalene and Sebastiano del Piombo’s large Martyrdom of St. Agatha. The prominent green curtain flung back in the Venus of Urbino mimics the custom of keeping portraits with explicit or illicit content—such as courtesans—covered with silk cloths. Titian evidently used the same model appearing in the Venus for several other portraits for the dukes of Urbino, suggesting she might be Guidobaldo’s mistress.

Rather than a specific person, however, Titian’s Venus more likely represents a generic and idealized female beauty. She corresponds to the image type known as belle donne (beautiful women) he helped popularize in Venice. Women appear in such pictures, sometimes in the guise of ancient heroines, according to a standard formula: fair skin; loose blonde hair; flirtatious glance; provocative clothing or nude; a floral offering; and expensive jewelry. Contemporary love poetry provided the inspiration for these canons of beauty, grounded in lustful male fantasy, celebrating the beloved’s duality as a chaste yet erotic companion.

Venus and Renaissance marriage

Titian based his composition for the Venus of Urbino on his colleague Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, featuring a naked woman reclining as if asleep in a sunny meadow. The overt sensuality of the imagery relates to the special role of Venus as goddess of love, sexuality, fertility, and beauty. Because of this, she also served as the patroness of marriage. The subject of the sleeping Venus was central to epithalamia (songs or poems celebrating marriage) popular in Greek and Roman antiquity, and revived in Renaissance Italy.

One of Titian’s innovations involves the liberation of the nude, once hidden inside furniture, to a subject for an independent easel painting. Given her connection to marriage, Venus became a fashionable subject for artists to paint on cassoni, the large wedding chests containing trousseau and stored in a newly-wed couple’s nuptial chamber.

This may explain the oblong horizontal format of the Venus of Urbino, which resembles earlier fifteenth-century panels found on the underside lid of Florentine cassoni. This is the format of Titian’s earlier painting, Sacred and Profane Love, which more certainly commemorates a marriage and also depicts Venus disrobed alongside a bride.

Why Titian was asked to paint the Venus of Urbino is unclear, though it possibly commemorates the 1534 wedding of duke Guidobaldo to Giulia da Varano (then merely ten years old). Numerous elements of the painting allude to marriage. The device of a sleeping dog (here a toy spaniel) often symbolizes marital fidelity. The bouquet of roses, also embroidered on the bed cushions, are associated with Venus and the constancy of love, as is the myrtle plant prominently silhouetted in the background window. Titian’s Venus may have been commissioned on the occasion of Giulia’s sexual maturity, when she and Guidobaldo could rightfully consummate their marriage occurring four years prior.

Audiences would have recognized the woman’s distinctive hairstyle in the Venus of Urbino as the type for engaged young women. Brides sported blonde hair (often dyed) spread loosely over the shoulders and interlaced with golden filaments and fitted with a fancy tiara. In this case, the braids atop her head correspond to such an item and are styled to mimic it. Her expensive pearl earrings, ring, and bracelet may relate to the practice of bestowing such jewelry on brides. Attendants gather a lavish blue and gold dress from two large cassoni in the background, alluding to dowry goods but also Venetian engagement ceremonies when fancy gowns were worn.

Focal point of the composition

Titian leaves no doubt that the woman’s pelvis is the focal point of the composition. The geometry and spatial construction pull our attention directly to it. The actual lines of the middleground partition wall and rear edge of the bed intersect at her genitals, practically forming a bull’s-eye. Though some hesitate to address it, her groin, along with the action she performs there, is the visual and thematic axis upon which the narrative turns.

At one level, Venus’s covering of her genitals with her hand involves an erudite allusion to ancient Greek and Roman sculptures of the Venus pudica (“modest Venus”), known in Titian’s time through dozens of copies in various sizes and media. Like her classical model, the pose of Titian’s figure ironically emphasizes rather than conceals her sexual organs. Yet unlike the Venus pudica, Titian’s nude appears to be contracting her fingers in a caress—instead of merely hiding her genitalia from view. Titian playfully accentuates this action by balancing the twist of her left hand with the knotted draperies in the upper left corner— a visual rhyme lending a further erotic charge.

Some modern scholars see the Venus of Urbino as nothing more than a sexy pinup for elite clientele. Others reason that such a label unfairly judges the image according to modern sexual paradigms. For social historians of art, dismissing the picture as mere pornography ignores its more complex functions as a marriage picture rooted in sixteenth-century customs for Italian brides and grooms.

Art historian Rona Goffen convincingly argues that this matrimonial context explains the woman’s seductive glance and gesture of masturbation, both of which anticipate the husband in the bridal chamber and consummation of marriage. Renaissance medical theories advised married couples that simultaneous orgasm during intercourse, as well as the woman’s positioning on her right side, increased probability of conceiving children. Women were encouraged to self-stimulate if needed to achieve this outcome.

Female nudes and the gaze

Numerous variations of the Venus of Urbino attest to its notoriety in Renaissance Europe. It has also profoundly shaped subsequent formulas for representing the nude female body in the western canon. Initially construed as a private matrimonial image, this theme evolved from the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries as a conventional academic subject-matter for artists. Its influence can be measured in works by renowned painters such as Diego Velázquez, Peter Paul Rubens, Rembrandt, Francisco de Goya, and Jacques-Louis David.

The visual traditions of the female nude have been challenged by feminist interventions in the history of art. Art historians increasingly see works such as the Venus of Urbino as symptomatic of sexist social structures that reduce women—real or painted—to passive sex objects displayed for visual consumption. This phenomenon, now referred to as the male gaze, is problematic since it recognizes that women are represented in visual culture from an assumed male heterosexual viewpoint.

By the eighteenth century, the erotic spectacle of the Venus of Urbino for male audiences is clear. It forms the centerpiece of Johan Zoffany’s depiction of the Uffizi galleries, where over twenty men have gathered to scrutinize esteemed artworks throughout the history of art—their gratification seemingly sexual as well as aesthetic. Perhaps most notorious is Édouard Manet’s reinterpretation of the Venus of Urbino in his painting of Olympia, which replaces Venus with a prostitute. This choice shocked the nineteenth-century French public and has since, somewhat unjustly, distorted readings of Titian’s picture as a similarly vulgar episode of illicit seduction.

Notes:

[1] Quoted in Rona Goffen, “Sex, Space, and Social History in Titian’s Venus of Urbino,” in Titian’s Venus of Urbino, ed. Rona Goffen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 72–73

Additional resources:

Read about gender in renaissance Italy

This work at the Gallerie degli Uffizi in Florence

Discover Titian’s Venus of Urbino on Google Arts & Culture

The art of lying: reclining figures through history from Art UK

Andrea Bayer, ed., Art and Love in Renaissance Italy (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008)

Omar Calabrese, ed., Venere Svelata: La Venere di Urbino di Tiziano (Milan: Silvana, 2003)

Rona Goffen, Titian’s Venus of Urbino (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Titian, Christ Crowned with Thorns

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Titian, Christ Crowned with Thorns, ca. 1570-76, oil on canvas, 280 × 182 cm (Alte Pinakothek, Munich)

Titian and Jacopo Palma il Giovane, Pietà

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Titian and Jacopo Palma il Giovane, Pietà, c. 1570-76, oil on canvas, 11’6″ x 12’9″ (Galleria Dell’Accademia, Venice)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

No photos

Figure \(\PageIndex{37}\): More Smarthistory images…

Correggio

Correggio, Jupiter and Io

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): Correggio, Jupiter and Io, 1532-33, oil on canvas, 163.5 x 70.5 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Correggio, Assumption of the Virgin

Fluttering drapery and naked limbs

“Frog leg stew” grumbled Girolomo Tiraboschi as he glanced up into the dome of the cathedral of Parma, where he served as a priest in the late 18th century. Correggio’s Assumption of the Virgin, a vortex of fluttering drapery and naked limbs, rose above him. Parma’s leading citizens had commissioned the fresco in 1522, shortly after the papacy liberated the city from the French king’s occupying forces. Crowning Parma’s most important sacred space, the fresco not only illustrates the Virgin Mary’s joyful reunion with her son, it also visualizes key Catholic doctrines, celebrates the city’s return to the Papal States (lands ruled by the Pope), and symbolizes the final union of the faithful with the divine at the end of time.

Numerous medieval texts recount the story of Virgin Mary’s final days. According to the popular Golden Legend, the Apostles were miraculously transported to the Virgin’s home at the time of her death. They performed the Last Rites and placed her body in a tomb, only to learn three days later that she, like Christ, had been bodily assumed into heaven.

Experiencing the fresco

In the cathedral of Parma, the narrative of the Assumption unfolds as the devotee moves from the main entrance, down the central aisle (the nave), toward the main altar located directly below the dome. From the entrance, the nave’s ceiling obstructs the view of the dome. Only St John the Baptist and St. Hilary of Poiters, the patron saints of Parma, are visible in the triangular niches (squinches) that support the dome. St. John embraces the Lamb, symbol of Christ, while St. Hilary gestures with one arm toward the nave and with the other points down to the altar, both directing the viewer to the liturgical focus of the cathedral.

Next, the Apostles come into view. These robust figures stand on a ledge executed in striking trompe l’oeil (“deceive the eye”) perspective around the octagonal base of the dome. Some shield their eyes from the brilliance of the divine light; others gesticulate excitedly, their draperies agitated not only by the energy of their gestures but also by the otherworldly force that pulls the Virgin upward. On the low wall behind the Apostles, wingless angels busy themselves with a variety of funerary rituals; some tend to the flames of oil lamps shaped like golden candelabra, others fill censors or burn fragrant branches of cypress.

The devotee moves forward to see what so astonishes the Apostles. The Virgin Mary appears seated upon a cloud that floats in the space defined by the dome. Frolicking angels, ranging in age from infants to adolescents, populate concentric bands of clouds that extend into the apex of the dome. Mary twists her body and opens her arms as she rises toward the golden light of heaven.

Adam and Eve appear on the Virgin’s right and left. Eve extends the apple, a symbol of her disobedience, toward the Virgin Mary; Adam touches his chest as if acknowledging his fault. This view of Mary, framed by Adam and Eve and rising toward the light, was the last seen by the lay viewer. Its message is clear: the Virgin Mary repairs the bond between the human and divine broken by the sinfulness of Adam and Eve. Her obedience to God’s will made her the chosen vessel of the Incarnation and earned her a place by Christ’s side in heaven.

Reserved for priests

At the time of the fresco’s creation, the faithful received the Eucharist (bread that has been consecrated, or ritually transformed, into the body of Christ, according to the Catholic doctrine of Transubstantiation) at the foot of the staircase leading to the main altar, precisely where Mary appears rising toward the light of heaven. The beardless figure of Christ becomes visible only further up the staircase, in the area reserved for the clergy. Christ hovers directly above the altar where the bread is consecrated. His white garment rises up as he descends to meet his mother, his arms raised in a powerful gesture that opens the heavens and raises the dead. This same divine power also turns the bread on the altar below into his body.

When the fresco is viewed from the main altar, directly below the dome’s apex, Tiraboschi’s disparaging comment have some validity. The viewer struggles to sort out the many limbs that hover above in extreme foreshortening, obscuring the narrative’s legibility. The narrative is clearest from the oblique viewpoint of the laity who approached the fresco from the cathedral’s nave. The clergy, who gazed up from the main altar or their seats in the choir, saw primarily the realm of heaven.

Extreme foreshortening

Correggio’s unusual and seemingly indecorous portrayal of Christ in extreme foreshortening, with his youthful legs exposed, draws attention to Christ’s physicality, and thus both to his Incarnation through the Virgin Mary and his bodily presence in the Eucharist. Painted during the first decade of the Protestant Reformation, Correggio’s fresco visually reaffirmed Catholic doctrines that had come under attack, in particular the doctrines of Transubstantiation, of Mary’s status as intercessor, and of the Church’s role in human redemption.

An illusion of heaven

In the sacred architecture of the Roman and Byzantine empires, domes were viewed as symbols of heaven. Correggio merged this symbolism with the Renaissance’s fascination for three-dimensional illusion. He transformed the dome from a solid surface into heaven itself. The dramatic di sotto in su (from below to above) perspective heightens the reality of the illusion. As the first follower of Christ, the Virgin Mary personifies the Church, the community of the believers. Through the Assumption’s daring foreshortening, Correggio reassured Parma’s citizens of the palpable reality of eternal salvation.

Paolo Veronese

Paolo Veronese, The Family of Darius before Alexander

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{13}\): Paolo Veronese, The Family of Darius before Alexander, 1565-67, oil on canvas, 236.2 x 474.9 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Paolo Veronese, The Dream of Saint Helena

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{14}\): Paolo Veronese, The Dream of Saint Helena, c. 1570, oil on canvas, 197.5 x 115.6 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Paolo Veronese, Feast in the House of Levi

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{15}\): Paolo Veronese, Feast in the House of Levi, 1573, oil on canvas, 18′ 3″ x 42′ (Accademia, Venice)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Transcript of the trial of Veronese

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Transcript of the trial: On Saturday, July 18, 1573, Paolo Caliari Veronese who lives in the parish of San Samuele, Venice was summoned to appear before the Holy Tribunal by the Holy Office [the inquisition], there he stated his name when asked. When asked what he did for a living, he responded, “I paint and make figures.”

Inquisition: Do you know why you are summoned here?

Veronese: No your honors.

Inquisition: Can you imagine what the reason is?

Veronese: I can.

Inquisition: Tell us.

Veronese: I was told by the priests, or rather by the Prior of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, whose name I don’t know, told me that he had visited here and that Your Great Lordships had commanded the Mary Magdalene replace the dog. I responded that that I would have happily done this and anything else for my and the sake of the painting, except that I did not believe that the figure of the Magdalene would look good there, for a variety of reasons, which I can speak to if I am given the chance.

Inquisition: What is the subject of the picture you are speaking of?

Veronese: It is a painting of the Last Supper, with Jesus Christ with his Apostles in the house of Simon.

Inquisition: Where is this picture?

Veronese: It is in the refectory of the Monastery of SS. Giovanni e Paolo.

Inquisition: Is it painted on the wall, on wood, or on canvas?

Veronese: Canvas.

Inquisition: How tall is it?

Veronese: Perhaps seventeen feet.

Inquisition: How wide is it?

Veronese: About thirty-nine feet.

Inquisition: Have you painted servants at the Lord’s Supper?

Veronese: Yes.

Inquisition: Tell us how many people there are, and each one’s activities.

Veronese: Below the owner of the inn, Simon, I put a carver, He came, I guess, for his own amusement, to observe the goings-on at the table. There are many other figures but I cannot remember, its been a long time since I finished the painting.

Inquisition: What was your intent regarding the man whose nose is bleeding?

Veronese: I intended him to be a servant, whose nose was bloody because of some accident.

Inquisition: And what did you mean by the armed man, clothed like a German, holding a halberd?

Veronese: That will take longer to explain.

Inquisition: Tell us.

Veronese: Painters take the same poetic license that poets and madmen take, and this is how I made these two soldiers, one drinking the other eating, at the foot of the stairs, though both ready for prompt action. It seemed appropriate to me that the wealthy owner of this house, a noble I understand, would have hired security such as these men.

Inquisition: And the figure dressed as a jester with a parrot perched on his hand, why did you represent him?

Veronese: He is decorative, as is customary.

Inquisition: Who are those at the Lord’s table?

Veronese: The twelve Apostles.

Inquisition: What is St. Peter doing, the first one?

Veronese: He is carving lamb, to pass it to the other side of the table.

Inquisition: And who is the other man, next to him?

Veronese: He holds a plate for St. Peter to fill.

Inquisition: What is he doing.

Veronese: He is picking his teeth with a fork.

Inquisition: Who do you believe was at the Last Supper?

Veronese: Christ was there with his Apostles. But there was more space, so I included other figures that I created.

Inquisition: Did anyone tell you to paint Germans, jesters, or buffoons in this picture?

Veronese: No. I was told to create the painting as I thought fit, it was large and could accommodate numerous figures.

Inquisition: Shouldn’t painters only add figures in keeping with the subject and the most important people portrayed? Do you freely follow your imagination without restraint, without good judgment?

Veronese: My paintings are made with all the consideration I can bring to bear on them.

Inquisition: Do you think it is appropriate that the Last Supper of Our Lord includes jesters, drunks, Germans, midgets, and the like?

Veronese: No, your honor.

Inquisition: Do you not know that Germany and other places are infested with heresy and that in such place they commonly fill their paintings with sacrilegious images, that denigrate the Holy Church and spread evil to the ignorant?

Veronese: Your Honor, that would be evil. I can only repeat what I previously stated, That I have followed what others, better than me, have done.

Inquisition: What has been done by those better than you? Which things?

Veronese: In the Pope’s chapel in Rome, Michelangelo rendered Our Lord, Jesus Christ, his Mother, Saint John and Saint Peter, and the court of heaven, all nude, including the Virgin Mary, in the midst movements without decorum.

Inquisition: Don’t you understand that in a painting of the Last Judgment, clothing would not be worn, that there is no reason to paint clothes? Among those figures there is nothing except what befits the spiritual—there are no jesters, no dogs, no weapons, or any such silliness. Do you think this comparison, or any other that this example or any other justifies the way you painted your picture, and are you still certain that the painting appropriate to its subject?

Veronese: Your honor, I do not mean to defend it, but my intent was only good. I did not consider these issues enough, thinking that since the buffoons were outside the place where Our Lord sits, it was proper.

In the end, the judges decreed that the artist must correct his painting within three months from the day of the reprimand, in accordance with the judgment of the Holy Tribunal, and that the additional costs would be paid by Veronese.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Accademia

Veronese from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Jacopo Tintoretto

Jacopo Tintoretto, The Miracle of the Slave

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{16}\): Jacopo Tintoretto, The Miracle of the Slave, 1548, oil on canvas, 415 x 541 cm (Accademia, Venice)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Jacopo Tintoretto, The Finding of the Body of Saint Mark

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{17}\): Jacopo Tintoretto, The Finding of the Body of Saint Mark, c. 1562-66, oil on canvas, 396 x 400 cm (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan)

Jacopo Tintoretto, The Origin of the Milky Way

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{18}\): Jacopo Tintoretto, The Origin of the Milky Way, c. 1575, oil on canvas, 149.4 x 168 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Jacopo Tintoretto, Last Supper

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{19}\): Jacopo Tintoretto, Last Supper, 1594, oil on canvas, 12′ x 18′ 8″ (San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice)

Andrea Palladio

Palladio, La Rotonda

Looking back and looking forward

At the top of a hill in northern Italy, not far from Venice, stands a majestic villa. Designed by Andrea Palladio, the Villa Almerico-Capra, commonly known as La Rotonda, would become one of the most recognizable buildings of the Renaissance. It is a building that consciously recalls ancient Roman classical models but its innovative design had a lasting impact for future generations of architects in Italy and abroad.

A building with four façades

As an architect, Palladio was acutely interested in engaging viewers, something he often accomplished by making use of striking façades. What makes La Rotonda extremely unique is that it displays not one, but four of them. Idiosyncratic choices do not always result in groundbreaking creations; a building with four façades could have easily ended up being bizarre, but Palladio was able to design a serene, sophisticated construction by emphasizing balance, visual clarity, and uniformity. The design of the building is completely symmetrical; it presents a square plan with identical porticoes projecting from each of the façades. At the center of the building, a dome emerges over a central, circular hall. Palladio was concerned with harmony and mathematical consonance and used the square and the circle as essential, yet elegant forms.

The importance of site

The picturesque qualities of the villa in relation to its environment are not coincidental. Palladio himself reflected on the landscape surrounding La Rotonda: “The loveliest hills are arranged around it, which afford a view into an immense theater.” In this way, La Rotonda presents four unique views: each of the porticoes is itself a place from which to contemplate the ever-changing spectacle of nature. At the same time, the villa also becomes a stage that can be contemplated from its surroundings. Because of its unique design, a façade is almost always visible: the viewer who walks around the villa never encounters a non-favorable angle.

A palazzo in the countryside

La Rotonda is perhaps the best known of the many country houses built in the Veneto in the sixteenth century. The popularity of villas at the time has to do with the changing Venetian economy. The Spanish and Portuguese voyages to America and Asia, along with Turkish military advances in the eastern Mediterranean, signified the demise of the Italian trade routes—which had been the primary source of wealth for the city-state of Venice. As a result, Venetians looked to the Terra Firma (their territories on the Italian mainland) to support their economy. It is at this time that agriculture became, for the first time, a significant economic source for the Venetian Republic. And yet, unlike other villas in the Veneto, Palladio designed La Rotonda without adjacent farm fields, or service buildings such as barns or warehouses.

A unique commission for a timeless edifice

La Rotonda was commissioned by Paolo Almerico, a retired prelate who returned to Vicenza after a career in the Vatican Court. Almerico sold his house in the city to retire in the countryside. For this reason, La Rotonda was not technically designed as a villa as much as an urban residence placed in the countryside. Almerico never thought of this space as an agricultural production facility, and Palladio himself classified the building as a Palazzo. The ecclesiastical career of Almerico had a definite impact on the building. The religious connotations of La Rotonda are palpable in the vibrant interior, which contrasts with the sober exterior. Inside, La Rotonda is a colorful and vivid space that looks more like a church than a household. In fact, many of the paintings make explicit connections to the religious life of Almerico, celebrating religious values and Christian virtues, such as temperance and chastity.

The exterior of La Rotonda also suggests the sacred. The edifice was influenced by ancient Roman temples (such as the Pantheon) and sacred complexes (such as the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia). By using ancient Roman temples as a model, Palladio incorporates religious overtones into an otherwise secular space. At the same time, La Rontonda has a perennial quality to it; Palladio’s use of classical elements emphasizes a universal architectural language.

Palladio, Teatro Olimpico

A spectacular space

In Vicenza, a town near Venice, a unique Renaissance theater has miraculously survived for over four centuries. A hidden gem built inside an abandoned fortress and prison, Teatro Olimpico gives form to the period’s knowledge of classical Roman architecture and puts into practice contemporary artistic developments like linear perspective.

The humanist theater and the new Renaissance stage

Italy of the sixteenth century witnessed the rising popularity of the theater as a cultural form and as a mode of entertainment. Theatrical productions had existed throughout the Middle Ages, but consisted mostly of religious enactments staged on temporary platforms in outdoor spaces, like town squares.

With the emergence of humanist culture in fifteenth-century Italy, developments in theatrical architecture and design went hand-in-hand with literary models that sought to reinstate the comedies and tragedies of ancient Rome. But architects interested in studying Roman art faced a problem: the celebrated theaters of ancient Rome had been dismantled or transformed into utilitarian spaces throughout the Middle Ages. Luckily, Renaissance architects were able to study the writings of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, whose Ten Books on Architecture explained how to construct a theater and described set decoration. A widely influential text, Andrea Palladio himself illustrated the first Italian translation of Vitruvius’ architectural treatise. From these books and the study of ancient ruins, Renaissance architects were able to form an image of classical Roman theaters. These theaters had a semicircular seating section, or auditorium, and an elaborate stage background called a scaenae frons.

At the same time that Renaissance artists were studying classical architecture, pictorial developments like linear perspective made their way into the theatrical stage of the sixteenth century—often in the form of painted backdrops displaying a city view. This innovation introduced a departure from the medieval stage, which had featured a row of scenographic houses representing Biblical locations. Whereas classical and medieval theatrical productions were free, popular events, the Italian Renaissance theater was a sheltered space of enclosure constructed for courtly elites and associations of erudite intellectuals.

A classically-inspired auditorium

Palladio was the most influential Renaissance architect. He was also a founding member of the Academia Olimpica—a group of scholars in Vicenza who sought to recreate the theatrical productions of classical antiquity. Though the Teatro Olimpico is the oldest surviving Renaissance theater, it was not the first permanent theater of the period. It was also not the first built by Palladio, who had previously designed theaters in Venice and Vicenza. The Olimpico was, nonetheless, his most ambitious theatrical project, and one that would put into practice his knowledge of classical architecture and contemporary art.

The Olimpico was not a theater built anew. Palladio designed his Roman-inspired auditorium inside an abandoned fortress. Refashioning an existing building forced the architect to adjust his plans. As a result, and unlike Roman theaters, Palladio’s seating area forms an elliptical curve rather than a semicircle. A highly decorated space, the curved auditorium is crowned by a columnated portico that is adorned with classically-inspired sculptures.

The scenographic city

The Teatro Olimpico’s stage features a magnificent three-tier façade or scaenae frons. Profusely decorated with classical columns, pediments, sculptures, and reliefs, the façade has five openings, of which the central one evokes a triumphal arch. Palladio and Vicenzo Scamozzi worked with limited materials—using wood, plaster, and stucco to create the effect of white, polished marble. The openings grant visual access to projected avenues, conveying the appearance of a city. Constructed using linear perspective, the passageways heighten the illusion by using forced perspective, which increases a fictional sense of depth—so an actor walking into the receding scenography would look like a giant in relationship to the buildings.

The perspectival passageways are a hallmark of the Olimpico, but their origins are unclear. Palladio died years before the grand opening of the theater, at a time when the inaugural performance was expected to be a pastoral comedy written by Fabio Pace. It was not until 1583, three years after Palladio’s death, that the Academia made the decision to perform the tragedy Oedipus King instead. This change required scenography depicting a cityscape instead of a landscape, and it is at this time that the Academia purchased the additional real estate required for the projected avenues. Scamozzi completed the construction of the auditorium and added the stage design, though perhaps following drawings produced by Silla, Palladio’s son and assistant. Whether they were the product of Palladio’s designs or simply inspired by him, Scamozzi’s stage constructions are extremely innovative—actually constructing in three-dimensions what had traditionally been a painted backdrop.

After the Olimpico

The result of Palladio and Scamozzi’s antiquarian knowledge and artistic innovation is a splendid and alluring space. Yet despite its enthralling qualities, the Teatro Olimpico quickly fell into disuse after its first production. Its influence is palpable, nonetheless, in two northern Italian theaters built shortly after the Olimpico: the 1590 Teatro all’antica in Sabbioneta, also built by Scamozzi, and the 1618 Teatro Farnese in Parma.