6.3: Judaism and art

- Page ID

- 67076

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Judaism and art

The early Israelites made sacrifices at the Holy Temple, and they were distinct from other Levantine peoples, each of whom worshipped their local gods.

Jewish history to the middle ages

by DR. JESSICA HAMMERMAN and DR. SHAINA HAMMERMAN

For every period of Jewish history, interactions with non-Jews have been essential to forming Jewish culture and identity. The early Israelites made animal sacrifices at the Holy Temple, and they were distinct from other Levantine peoples, each of whom worshiped their local gods.

The Diaspora

Although there is no archaeological evidence for it, the Hebrew Bible describes a Temple in Jerusalem erected by King Solomon, probably sometime during the tenth century B.C.E. The Bible also describes the Temple’s destruction at the hand of the Babylonians 500 years later. Since the fall of the first Temple, Jews scattered throughout the Levant and Mesopotamia, creating competing cultures. Rabbinical scholars realized then that it would be necessary to write down oral interpretations—and they set the blueprint for future generations who would debate and reinterpret Jewish laws. The best-known rabbinical scholar was Hillel (70 B.C.E. to 10 C.E.). Hillel developed methods for interpreting the Hebrew Bible that were flexible. Since its inception, Judaism has been subject to community ritual interpretation and context.

A new Temple was constructed a century after the first was destroyed when some Jews returned to the Land of Israel. In 70 C.E., at the Roman siege of Jerusalem, Jews dispersed throughout northern Africa, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. This widespread dispersion of Jews outside of the Land of Israel is called the Diaspora.

The Middle Ages

In the Diaspora, Jewish groups lived in both Muslim- and Christian-dominated areas. Local communities had distinct traditions, but the differences between those who came from Muslim areas and those who came from Christian areas was more pronounced. Jews who can trace their ancestry back to Central and Eastern European areas are now known as Ashkenazim, and those who come from the Islamic world are now known as Sephardim. Sephardic Jews technically trace their origins back to the Iberian Peninsula, but Jews from the historically Muslim lands of the Middle East and North Africa (referred to as Mizrahi and Maghrebi, respectively), have been conflated with contemporary Sephardim since they share many of the same customs. These labels did not become widely used until the 1960s, when Jews from Islamic lands emigrated into Europe, the United States, and Israel. On a global scale, these distinctions weren’t relevant until after World War II.

In both Ashkenazic and Sephardic communities, Jews in the Middle Ages had to pay taxes in exchange for communal autonomy. Just as they came to speak the vernacular languages of the non-Jews among whom they lived, they also adopted the architectural, musical, culinary, and literary styles of their neighbors.

Synagogues in Christian-dominated lands are sometimes drab on the exterior but extremely ornate on the inside. Synagogues in Muslim lands have domes and arches that mimic Islamic architecture, such as the Santa Maria la Blanca in Toledo, Spain, or the Algiers Grande Synagogue in Algeria.

In Europe, persecution of Jews began after the Roman Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, crusading mobs massacred Jews throughout Europe. Crusaders blamed Jews for crucifying Jesus, an accusation that was extended in order to claim that Jews were committing the ritual murder of Christian children, known as the blood libel.

Jews that lived in Europe were easy, early targets for Crusaders since the Muslims,from whom they hoped to wrest the Holy Lands, were far from home.. Throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Jews in Spain were subject to violent forms of anti-Judaism. The Spanish Inquisition forced conversions and expulsions of the many Jewish residents of the Iberian Peninsula.

Life for Jews in Islamic lands was comparatively tranquil. In areas dominated by Muslims, Jews in the Middle Ages were tolerated as a “dhimmi”—a people of the book. Unlike in the Christian world, Jewish people were not the only non-Muslim inhabitants (there were also Christians, Zoroastrians, Hindus, Buddhists, etc.). Jews were integrated into the economy, and they were allowed to practice their religion freely. Jews conducted business with non-Jews in the Middle Ages and the similarities in art, music, and food traditions speak to Jewish and non-Jewish interaction. But their communal lives remained mostly separate—Jewish dietary laws, or kashrut, meant that Jews had their own butchers, bakers, and even wine producers. The weekly Sabbath meant that Jewish merchants and peasants would refrain from work, while Christian or Muslim commerce might continue. And Jewish law forbid marriage outside of the religion, further solidifying boundaries between Jews and their neighbors—boundaries that in some later instances became walled ghettos within which Jews were forced to live.

Additional resources:

Daniel Boyarin, Border Lines: The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

Elisheva Carlebach, Divided Souls, 1500-1750 (New Haven: Yale University Press,2001).

Robert Chazan, The Jews of Medieval Western Christendom: 1000-1500 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Mark R. Cohen, Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).

Writing a history of Jewish architecture

How is it that the Jews, called by Scripture “the smallest of all the nations” (Deut. 7:7) merit a section on religious architecture placed alongside the glories of Christendom, Islam, and Buddhism? After all, the Jews today number something around fourteen million, the same number that existed before the massacre of six million in Europe and the dissolution of communities across Europe and the Arab world during the 1940s. This is a numerical highpoint. In previous centuries, the numbers were far smaller. Just on the basis of demography, then, it would be hard to justify the inclusion of Judaism in this history of art and architecture.

A national style?

More difficult, perhaps, from the first century through the establishment of modern Israel in 1948 Jews could not claim (or assert, as new European nations states did) a “national” identity or a “national” style of art based upon landed nationalism—categories that were of central importance to nineteenth and twentieth century constructions of architectural history and style. Theirs was a minority architecture, reflecting a minority existence.

The Temple of Solomon (c. 900 B.C.E.), modern scholars tell us, was a typical near eastern temple, while the great synagogues constructed at the turn of the twentieth century were art deco palaces. Even on a quality level, it is hard to include Jewish architecture among the great religious architecture of the world.

The greatest of Jewish building, the temples of Solomon (destroyed 586 B.C.E.) and Herod in Jerusalem (destroyed 70 C.E.) are long gone, and never again have Jews controlled extensive resources for building, nor land for construction. There is no Jewish parallel to Saint Peters (neither the “Old” one built by Constantine nor Julius II’s), nor Hagia Sophia, the temples of Varanasi, nor the Forbidden City. Small Jewish communities, stretched across the world from late antique Palestine to Kaifeng in 17th century China to contemporary America and Israel built synagogues—often buildings of great beauty and historical significance, but mostly pretty limited from an architectural standpoint. There were no Jewish benefactors to compete with Justinian or Saladin or the della Rovere; and virtually no government sponsorship of magnificent synagogues. Jewish architecture is always derivative of local styles and patterns, and responds to the needs of local minority communities. It never drove those styles. Jewish “architecture” through the ages was a hybrid architecture—a term scorned by nineteenth and twentieth century racial and national purists, but celebrated in our own “post-modern” age.

Longevity

What Jews lacked in territory, wealth and numbers, they made up for in longevity. Jews—short for “the Judeans,” trace their cultural heritage, and sometimes their physical lineage, to the biblical patriarchs—Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (also called Israel) and to the land of Israel (called in Roman times Judaea)—an unbroken chain of 3000 years. This is not just an “imagined” history. No other western community can assert—based upon rich documentary and physical evidence—to have encountered both Cyrus the Great and Innocent III, Caligula and Mohammed, Victoria, Stalin and Rembrandt. Though a minority, Jews maintained rich mimetic traditions across the empires that make up the “Western world,” and an astonishingly complex book culture that has sustained their sense of group cohesion. From antiquity to modern times, it was (and in many ways, still is) possible to travel from Jewish community to Jewish community from Persia to Spain and beyond—as travelers did—and find Jews who shared an all encompassing religious culture—even if they ate “strange” (though always kosher) foods, dressed “funny” (though males still wore the biblically mandated ritual “fringes”) and practiced “strange” local liturgical customs. Not speaking the same vernacular language, a visitor from, say, Germany might have communicated with his hosts in, say, Egypt, by drawing upon mix of “peculiarly pronounced” Hebrew and Aramaic gained through exposure to vast quantities of canonical religious texts.

Jews and their texts—not always together—have been active in what some textbooks still call “the Western Experience” from its beginning. The religious traditions associated with Jesus and Mohammed both assert that Jewish scripture, and interaction with Jews, is essential their own revelations, both of which assert relationship by virtue of having “superseded” the revelation of Moses. In other words, Jews “matter” to Christians and to Muslims, and by virtue of living among them, Christians and Muslims “mattered” to Jews.

The study of Jewish art and architecture

The academic study of Jewish architecture developed from the eighteenth century onward, when Christian Hebraists and bible scholars developed interests in biblical architecture—the Mosaic Tabernacle, the Solomonic Temple and the Herodian Temple—the latter visited by Jesus, who according to the Gospels predicted its destruction in 70 C.E. under emperor Vespasian. Post-“biblical” Jewish architecture did not become a focus of research until discoveries by the Palestine Exploration Fund of late antique synagogues during the 1860s. Medieval and early modern buildings took a bit longer to occasion scholarly interest. Jews in 19th century Europe, America and to some degree Islamic lands and south Asia, were engaged in a full-scale building boom; the largest since Herod the Great’s rebuilding of the Jerusalem Temple beginning 20/19 B.C.E. Newly emancipated and emancipating communities asserted their presence by building huge synagogues, experimenting with a wide range of forms, from neo-Egyptian to neo-classical and neo-moresque, eventually settling upon the modern yet traditionalist tones of art deco.

Only at the end of the 19th century did scholars begin to look back and study “Jewish art,” including Jewish architecture; often looking—whether intentionally or not—for roots for the contemporary boom in earlier periods. Hoping to prove that “Jews do art too,” Jews of all stripes hoped to prove their humanity through the creation and study of Jewish art. It was only in post-war New York that the first—and perhaps still the best—comprehensive surveys of Jewish religious architecture were written, both by art historian/architect Rachel Wischnitzer. These were entitled European Synagogue Architecture and Synagogue Architecture in America. By then, the State of Israel had been established, and “Jewish art”—including architecture—became the national art.

The canonical book of this process was Cecil Roth’s Jewish Art: An Illustrated History, first published in Hebrew in 1958 and still in print in Hebrew. This anthology brought together scholars who had been scattered throughout the world due to the War to present a comprehensive history, from Solomon to the present. Architecture—until the modern period, all of it “religious” appears in every period and in almost every article, with some articles dedicated to this subject. The study of Jewish architecture has been of particular interest to Israeli scholars, but also to Americans and Europeans, and the Hebrew University’s Center for Jewish Art has sent teams across the world to document historical synagogues—most no longer used. In Europe, this work takes on additional significance, as it has been spawned by a real interest to regain a now-lost heritage—particularly in the East, as Europe, particularly since the fall of Communism, has sought to develop a more tolerant European tradition and usable history.

In recent years, Jewish visual culture has been deeply assimilated into the academic study of Judaism, really for the first time. Cultural historians, working with art historians and architectural historians, have begun to focus upon the very elements of Jewish “minority” architecture that in previous generations were often spurned. The process by which a small minority group melded with its general environment, transforming and being transformed within that environment has become the stuff of contemporary scholarship. In many ways, the Jews have been the “canary in the coal mine,” the test case for theoretical discussion of what it means to live in diaspora and to be Europe’s first, earliest and most intimate—colonized people.

Medieval synagogues in Toledo, Spain

By the time the first surviving synagogues were built in Spain, Jews had lived there for more than a thousand years. The first Jews likely arrived on the Iberian peninsula among the Roman conquerors and colonizers who flowed there in the first century C.E. Jews were persecuted by Christians during the Late Antique period (beginning in the 4th century), but when Muslim rule was established in 711, the legal and economic status of Jews improved. Often well integrated into the governments and economies of the cities in Muslim Al-Andalus, many Jews spoke Arabic and wore the same clothes as their Muslim neighbors.

Although population estimates for pre-modern periods are notoriously unreliable, one scholar has estimated that the Jewish population of Spain grew to be larger than the Jewish populations of every other part of the medieval world combined. Given the size and wealth of the Spanish Jewish communities of Al-Andalus, we can be certain that they built many synagogues in the quarters of the cities where they lived, but none survive from before the south of Spain was reconquered by northern, Christian rulers. Spain’s most remarkable medieval synagogues are found in former Islamic capitals, but they were built after these cities were again governed by Christians.

By the late Middle Ages, there were at least eleven synagogues in the city of Toledo in central Spain. Two of these—the Samuel Halevi Abulafia synagogue and the Ibn Shoshan synagogue—stand only a few blocks apart in the old Jewish quarter. Both synagogues display a style inspired by the Islamic buildings that surrounded them, sometimes called Mudéjar. This style was used by Muslim, Christian, and Jewish patrons and builders living in parts of Spain formerly governed by Muslims. The earlier Muslim builders had themselves borrowed from the cultures that preceded their arrival by including details that had been popular with Romans and Late Antique Christians in Spain, such as reused columns, Corinthian capitals and horseshoe arches.

A twelfth-century synagogue for Toledo’s Jewish community

The Ibn Shoshan Synagogue was likely first built around 1180, and was probably renovated by a member of the Spanish royal court in the thirteenth century before it was converted into a church (renamed Santa María la Blanca) in 1411. The bimah, Torah ark, and seats for the congregation were destroyed when the building was converted into a church. All that remains from the synagogue is the architecture.

The interior is divided into five aisles by four rows of stout octagonal piers. The piers carry rows of capitals decorated with stucco pinecones and volutes, surmounted by giant horseshoe arches.

Above the arches are layers of low-relief stucco tendrils and roundels, scallop shells, geometric interlacing, and rows of blind arches with multiple lobes (called poly-lobed arches), a wealth of surface decoration that recalls the type found in earlier Spanish buildings like the Great Mosque at Cordoba.

We know this wasn’t simply a local Toledan style, but one popular in other parts of Spain, because the Jewish community to the north in Segovia built a very similar synagogue, now destroyed, at almost the same time.

A private synagogue for a royal advisor

Almost two hundred years later, around 1360, a new synagogue was built in a different but related style by Samuel Halevi Abulafia, treasurer and advisor to the Spanish King Pedro I of Castile. Unlike the Ibn Shoshan synagogue, this one was private, and attached to Halevi’s palace, although it would have been a significant monument in the neighborhood given its height.

Instead of being divided into aisles by rows of arches, the Samuel Halevi Abulafia synagogue (later known as the church of El Transito de Nuestra Señora) is dominated by a soaring, open hall that is oriented towards a triple-arched Torah niche. The upper parts of the interior walls and the wall surrounding the Torah niche are blanketed with low-relief stucco decoration.

Right underneath the decorative wooden ceiling are ranks of colonnettes supporting poly-lobed arches that hug the wall, very similar to those at the Ibn Shoshan synagogue nearby. Below these are geometrically organized patterns of leaves, flowers, scallop shells, and interlacing tendrils, as well as the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Castile (a three-turreted castle). A wealth of Hebrew and Arabic inscriptions praise King Pedro, the building’s architect, Don Meir Abdeil, and the royal treasurer and patron of the synagogue, Samuel Halevi, who is described as “prince among the princes of the tribe of Levi.” Inscriptions also quote literary and religious texts, including the Bible and the Qur’an.

This was the same style that King Pedro (who was Catholic) favored in his own palace architecture, making it a decorative language common to the Muslim, Christian and Jewish elites. Samuel may have wanted to celebrate his own integration into the power center of the kingdom by imitating its court style, but unfortunately his success was short-lived. Soon after the synagogue was completed, Pedro had him arrested, tortured, and executed.

Though the Jewish population in Spain was increasingly persecuted and finally in 1492, officially banished (unless they converted to Christianity), these synagogue structures attest to their long presence, and to the close interconnections between Muslim, Jewish, and Christian cultures in medieval Spain.

Additional resources:

History of Santa María la Blanca on toledomonumental.com (in Spanish)

Website of the Museo Safardi, El Transito (in Spanish)

History of the El Transito Synagogue from Beit Hatfutsot, The Museum of the Jewish People

Norman Roth, “New Light on the Jews of Mozarabic Toledo,” AJS Review 11 (1986), pp. 189-220.

Convivencia: Jews, Muslims and Christians in Medieval Spain, ed. Vivian B. Mann, Thomas F. Glick and Jerrilynn D. Dodds (New York: The Jewish Museum; George Braziller, 1992).

R. Wischnitzer, The Architecture of the European Synagogue (Philadelphia, 1964), p. 35.

The Golden Haggadah

On the eve of the Jewish holiday of Passover, a child traditionally asks a critical question: “Why is this night different from all other nights?” This question sets up the ritual narration of the story of Passover, when Moses led the Jews out of slavery in Egypt with a series of miraculous events (recounted in the Jewish Bible in the book of Exodus).

For the last and most terrible in a series of miraculous plagues that ultimately convinced the Egyptian Pharaoh to free the Jews—the death of the first born sons of Egypt—Moses commanded the Jews to paint a red mark on their doors. In doing so, the Angel of Death “passed over” these homes and the children survived. The story of Passover—of miraculous salvation from slavery—is one that is recounted annually by many Jews at a seder, the ritual meal that marks the beginning of the holiday.

A luxurious book

The book used to tell the story of Passover around the seder table each year is a special one, known as a haggadah (haggadot, pl). The Golden Haggadah, as you might imagine given its name, is one of the most luxurious examples of these books ever created. In fact, it is one of the most luxurious examples of a medieval illuminated manuscript, regardless of use or patronage. So although the Golden Hagaddah has a practical purpose, it is also a fine work of art used to signal the wealth of its owners.

A hagaddah usually includes the prayers and readings said during the meal and sometimes contained images that could have served as a sort of pictorial aid to envision the history of Passover around the table. In fact, the word “haggadah” actually means “narration” in Hebrew. The Golden Haggadah is one of the most lavishly decorated medieval Haggadot, containing 56 miniatures (small paintings) found within the manuscript. The reason it is called the “Golden” Haggadah is clear—each miniature is decorated with a brilliant gold-leaf background. As such, this manuscript would have been quite expensive to produce and was certainly owned by a wealthy Jewish family. So although many haggadot show signs of use—splashes of wine, etc.—the fine condition of this particular haggadah means that it might have served a more ceremonial purpose, intended to showcase the prosperity of this family living near Barcelona in the early fourteenth century.

Gothic in style

The fact that the Golden Haggadah was so richly illuminated is important. Although the second commandment in Judaism forbids the making of “graven images,” haggadot were often seen as education rather than religious and therefore exempt from this rule. The style of the manuscript may look familiar to you—it is very similar to Christian Gothic manuscripts such as the Bible of Saint Louis (below). Look, for example, at the figure of Moses and the Pharaoh (above). He doesn’t really look like an Egyptian pharaoh at all but more like a French king. The long flowing body, small architectural details and patterned background reveal that this manuscript was created during the Gothic period. Whether the artists of the Golden Haggadah themselves were Jewish is open to debate, although it is certainly evident that regardless of their religious beliefs, the dominant style of Christian art in Europe clearly influenced the artists of this manuscript.

Cross-cultural styles

So the Golden Haggadah is both stylistically an example of Jewish art and Gothic art. Often Christian art is associated with the Gothic style but it is important to remember that artists, regardless of faith, were exchanging ideas and techniques. In fact, while the Golden Haggadah looks Christian (Gothic) in style, other examples of Jewish manuscripts, such as the Sarajevo Haggadah, blend both Christian and Islamic influences. This cross-cultural borrowing of artistic styles happened throughout Europe, but was especially strong in medieval Spain, where Jews, Christians and Muslims lived together for many centuries. Despite periods of persecution, the Jews of Spain, known as Sephardic Jews, developed a rich culture of Judaism on the Iberian Peninsula. The Golden Haggadah thus stands as a testament to the impact and significance of Jewish culture in medieval Spain—and the rich multicultural atmosphere of that produced such a magnificent manuscript.

Additional resources:

The Golden Haggadah at the British Library (digital manuscript)

Digital Hebrew Treasures from the British Library Collections (British Library blog)

About the Golden Haggadah, from the British Library and more here

Beṣalel Narkiss, The Golden Haggadah A Fourteenth-Century Illuminated Hebrew Manuscript in the British Museum (London: Eugrammia Press, 1970).

Joseph Gutmann, Hebrew Manuscript Painting (New York: Braziller, 1978)

Marc Michael Epstein, The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011).

Katrin Kogman-Appel, “Coping with Christian Pictorial Sources: What Did Jewish Miniaturists Not Paint?” Speculum, 75 (2000), pp. 816-58.

Katrin Kogman-Appel, Illuminated Haggadot from Medieval Spain. Biblical Imagery and the Passover Holiday (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006).

Katrin Kogman-Appel, Jewish Book Art Between Islam and Christianity: the Decoration of Hebrew Bibles in Medieval Spain (Lieden: Brill, 2004), pp. 179-85.

Julie Harris, “Polemical Images in the Golden Haggadah (British Library Add. MS 27210),” Medieval Encounters, 8 (2002), pp. 105-22.

Book of Morals of Philosophers

by DR. RONNIE PERELIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Videos \(\PageIndex{1}\): Sefer Musre Hafilosofim (Book of Morals of Philosophers), 13th -15th century, ink and opaque watercolor on parchment, Spain (The Hispanic Society of America, New York)

The manuscripts of Luis de Carvajal

A secret faith

In 1596, Luis de Carvajal, along with his mother and sisters, were condemned to the flames of an auto da fé in Mexico City for their secret adherence to Judaism. The Carvajals were conversos, descendants of Jews who converted to Catholicism often under great duress in Spain and Portugal during the late middle ages. A minority of these converts maintained their ancestral faith in secret, braving the wrath of the Inquisition.

The Carvajals moved to Mexico for the same reason other Spaniards left the Old World for the New—economic opportunities and the chance to remake themselves in a new land. While the Inquisition only functioned in the Americas beginning in 1571, many conversos migrated to the ports and major urban centers of the Americas from the earliest days of Spanish conquest and colonization in the early 16th century. Carvajal’s uncle, also named Luis de Carvajal, was a decorated conquistador who was named the governor of the frontier territory of the Nuevo Reino de León in the Northeastern part of modern-day Mexico, and he invited relatives to join him in New Spain. Though he was a devout Catholic, much of his family, including his nephew Luis, who worked as his main assistant, were crypto-Jews. Eventually the secret unraveled, and the family was arrested by the Inquisition in 1589. The younger Luis, his mother, and his sisters all asked for mercy and were placed in a monastery to serve out their penance. The uncle was stripped of his position and exiled; he died in prison.

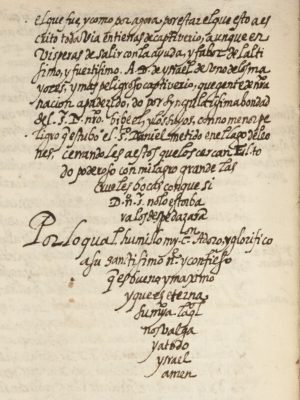

A life story lost and found

Soon after the younger Carvajal was released from the monastery, he began to compose an electrifying spiritual autobiography. He was a trained calligrapher and he wrote his life story in tiny, lucid script in a small leather-bound book that he kept hidden on his person throughout his travels. In these writings, he charts the guiding hand of Providence in his spiritual adventures, and his last entry tells of his planned escape to Italy. Sadly, Carvajal and his family were arrested before they made it to safety, and the autobiography which was meant to declare God’s mercies was found and used by the Inquisitors as evidence against them.

The autobiography, along with some of Carvajal’s other writings, were preserved with the extensive trial records and stored in the Mexican National Archives until they were mysteriously stolen in 1932. These documents were thought to have been lost for over eighty years, until they resurfaced and were identified as the long-lost texts by Leonard Milberg, a renowned collector. Milberg alerted the authorities and arranged for the return of these documents to Mexico.

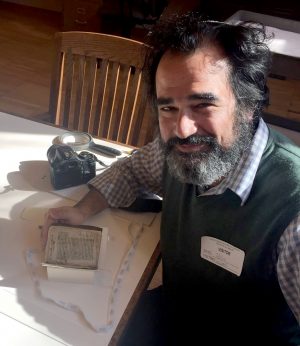

Before their official return, however, the manuscripts were put on display at the New York Historical society, where I had a chance to look at them up close. I have been working on Carvajal’s life story for the past 15 years and I was overjoyed to finally see his handwriting and read the lines he penned with such passion. I—and all of the scholars who have investigated this sensational case of crypto-Jewish activity in the heart of colonial Mexico—had previously relied on a transcription of Carvajal’s autobiography made by Alfonso Toro a few years prior to the theft of the manuscripts. After many years living with this text, analyzing, contextualizing, and turning it around in my head, it was a real thrill to sit with the original, up close.

New discoveries, new questions

The small bundle of manuscripts seemed to be inviting me in with their neat lines of tiny script. The first section was like meeting an old friend, or seeing the face of a longtime pen pal. I knew the lines of Carvajal’s autobiography inside and out, but I had never seen them in his own hand, nor did I know about the small side notes and elegant arrangement of the heading—the dedication to the Lord of Hosts that announces the beginning of his tale—nor the way he arranged the last lines in a final triangular flourish. Those details point to the fact that it was a text he went back to, added to, and revised. It also tells me that he really thought that he was about to escape the shadow of persecution and that his story of trials and tribulations was coming to a favorable end.

But then I encountered works I had never known about like El modo que es de Rezar, a guide to prayer for himself and for his fellow secret Jews in Mexico, and a list of the acts of mercy that the “most high God performed for Joseph”—a review of the major events of his short and tumultuous life.

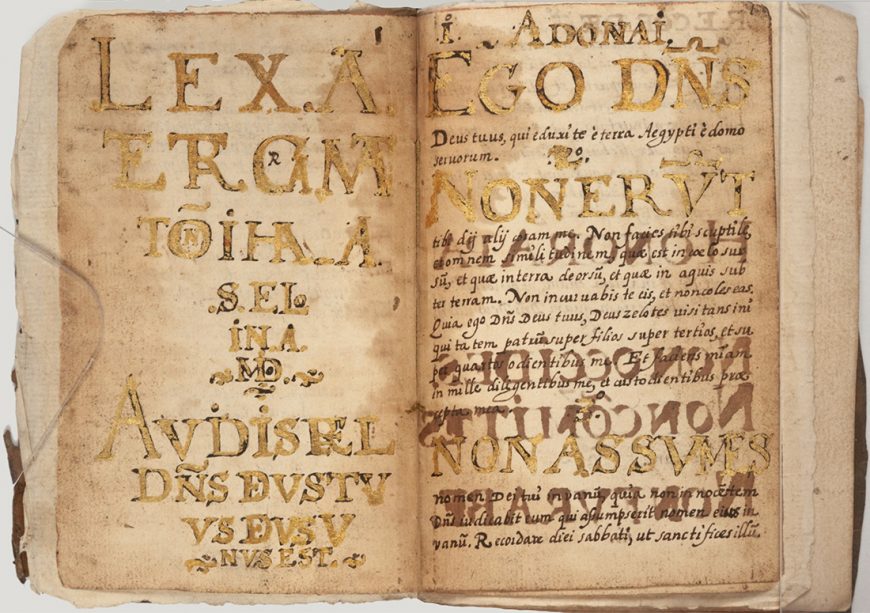

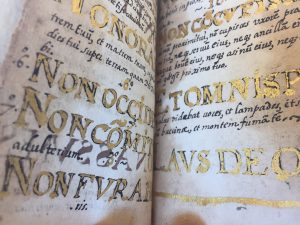

Right before this list, which takes up two pages, I found a section with the ten commandments in Latin, written out in beautiful large letters with gold leaf. New questions emerged: I knew Carvajal was an expert calligrapher, but where would he have had access to the materials and knowledge of the technique to apply the gold leaf?

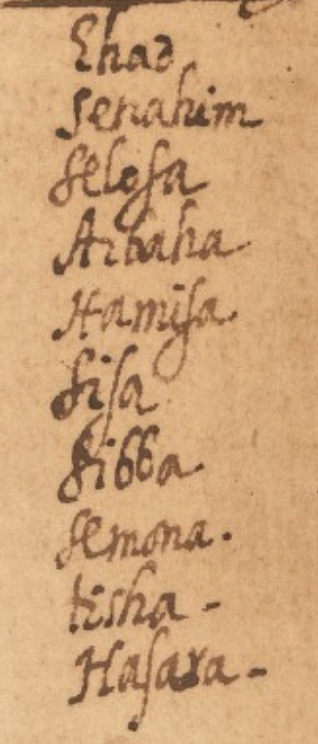

There is another page towards the end with a list of Jewish holidays and their corresponding Christian dates, along with another column featuring the name of the Hebrew months and a list of transliterated Hebrew numbers from one to ten—a Hebrew primer for a fully Latinized Converso Jew? What follows is even harder to understand—some psalms in Latin and some prayers in Portuguese, along with some deeply cryptic lists that seem to be mystical codes waiting to be deciphered.

More to decipher

The story of the Carvajal family has intrigued historians of colonial Mexico and has caught the imagination of a wide range of Mexican intellectuals and artists. Their experience is often read as an exemplary tale of the abuses of religious authority and the struggle for freedom of belief. I believe that the story of the Carvajals also complicates and enriches our understanding of Latin American religious history and points to the diversity of colonial society and the dynamism of religious creativity and expression that can still speak to spiritual seekers today.

Now that these texts have been digitized and the originals are securely back in Mexico, scholars will be able to explore and ask more questions of these beguiling records of a vibrant and short-lived religious life.

Additional resources:

Digitized version of the Luis de Carvajal manuscripts from Princeton University Digital Library

“A Secret Jew, the New World, a Lost Book: Mystery Solved,” The New York Times, January 1, 2017

Ronnie Perelis, Narratives from the Sephardic Atlantic: Blood and Faith (Indiana University Press, 2016)

Altneushul, Prague

In architecture, there is often a dominant mode of design in a given country or region at a particular moment in history. In central and western Europe during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it was customary to use Gothic elements such as pointed arches, rib vaults, and thin walls filled with stained glass.

But what about minority groups? Did they follow the trends of the majority or were they told what and how to build by the majority culture? Did the minorities have architects of their own on whom to rely, or were the minority members excluded from certain professions? We know about exclusion and discrimination from modern history. But what happened in the later middle ages?

Jews in Medieval Europe

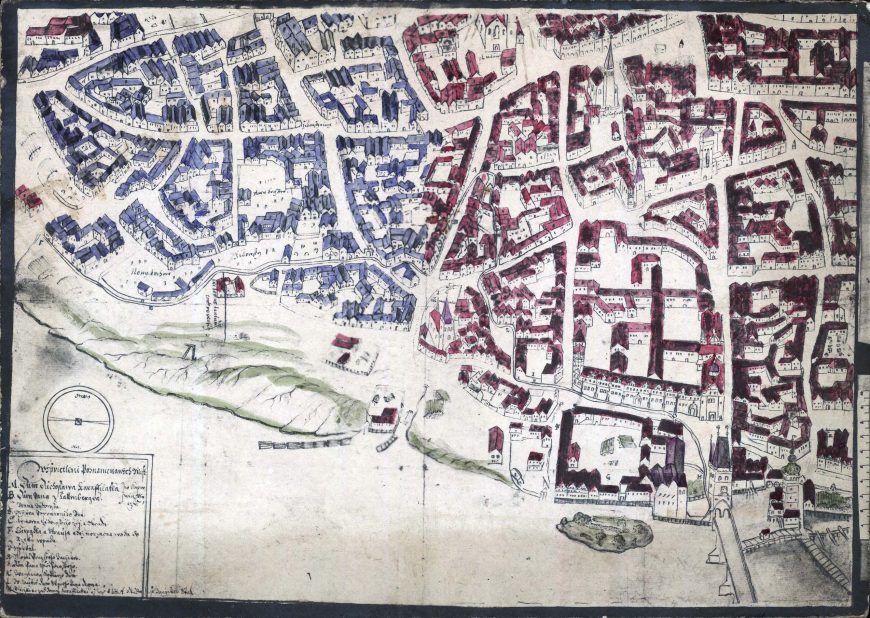

For centuries, Jews were the most noticeable minority in Europe. They lived only in certain regions, and were excluded from others. Their numbers were usually restricted, even in places where they were allowed to live. Nevertheless, Jews were useful members of society, in part because most Jewish men were literate—they were, and still are, expected to read their prayers (poor Roman Catholics had no schools and relied on priests to read on their behalf). Literate people could be useful in commerce and in keeping records, so some rulers allowed Jews to live in their cities. Often, there was a district designated for Jews, perhaps near the commercial district of a city, near the city walls, or near the palace of the ruler whom they served, (there were formal walled ghettoes only from the mid-sixteenth century onward).

Synagogue architecture

Every Jewish community had to have a place of worship, called a synagogue (from a Greek word related to assembling). Only a few rules governed the design of a synagogue; these rules were found in the Talmud. Later congregations of Jews adhered to these rules as best they could, despite the restrictions on their residence and use of land. Ideally, a synagogue’s focal point, the end of the building’s central axis, would face Jerusalem (to the southeast from the city of Prague).

The synagogue would contain carefully hand-written scrolls of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible that were held in chest known as a Torah ark when not in use. The ark was located at the building’s focal point. When the scrolls were removed from their storage chest, they would be carried ceremoniously to the center of the synagogue where the elders of the congregation would mount a low platform (bimah) and place the scrolls on a reading table. It would be an honor to be called to read to the congregation. In addition, no one was allowed to live above the synagogue; religious activity was to have pride of place and women would not occupy the same part of the building as men in order to avoid distracting the men from their prayers. Animals and other unclean things were not be allowed to defile the synagogue interior.

The Altneushul: a Gothic synagogue

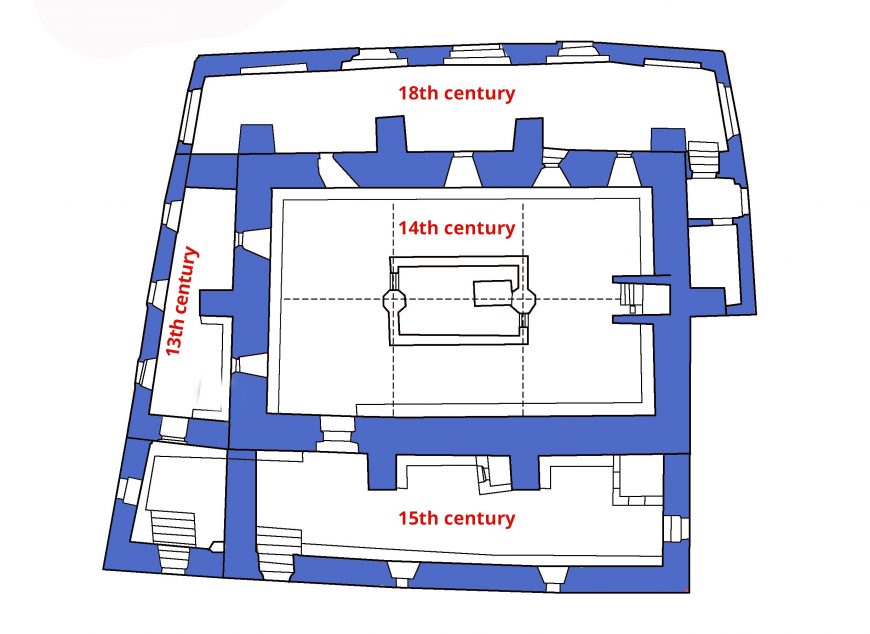

An important late medieval synagogue in Prague is called the Old New Synagogue because the city later gained a newer New Synagogue. It is generally known as the Altneushul in Yiddish. It seems to have originally been a small rectangular building erected in the thirteenth century, but late in that century or in the next one, the original synagogue was enlarged. Both stages of construction were apparently designed and built by Christians, because Jews were either formally or tacitly excluded from the guilds (trade associations) of the building crafts. An architect who at other times worked on churches seems to have been in charge because ornamental details are similar to those of a local church; the architect was therefore almost certainly Roman Catholic.

The synagogue stands in what was once the heart of the Jewish quarter. Its floor is lower than the level of the street in order to allow the congregation to utter the words of Psalm 130:1, “Out of the depths, I cry to Thee, O Lord.” The location has become all the more noticeable over time as the level of nearby streets has risen with re-paving, and as Pařížská (Paris Street), just to the east, was built in the nineteenth century to clear part of the old, crowded Jewish neighborhood.

The Altneushul, beyond the vestibule, is a rectangle about 26 feet wide and 45 feet long. It is composed of six bays arranged in two aisles, each with three bays. On the long east-west axis in the center of the building, two slender octagonal pillars allow the interior to be wider than it would have been without these supports. Leaf forms adorn the capitals.

Rib vaults cover each bay, but unlike the four-part, X-shaped ribs found in many Gothic-style vaults, those at the Altneushul have an extra, fifth rib, probably to help ensure stability; the same design can be seen in some secular and Christian buildings of the time. The bimah stands between the octagonal pillars in the center of the synagogue, and the ark on the eastern wall terminates the principal axis of the interior.

A place for prayer and study

This is clearly not the plan of a church. Jews had no need for a church plan with a nave, side aisles, chapels, and a transept because their rituals and customs differed from those of Roman Catholics. Instead, the plan of the Altneushul is more similar to the plan of certain secular buildings, as well as to some chapter houses. The plan of a meeting room was useful for a synagogue in which men meet to read and discuss religious doctrine. When possible, Jews and the Christians would not have wanted to imitate each other’s religious architecture, although in some of the simplest churches, chapels, and synagogues, a single room had to suffice for the congregation. Nevertheless, because members of both religions used the same builders, the individual components or ornamental details of the various buildings often resemble each other in design. The Altneushul has only plant decoration, because at that time, Jews would not allow images of human beings within a religious context.

Seats and desks are distinctive features of a medieval synagogue; medieval churches had no seats and there was no need for desks since most Christians were not literate. Seats are necessary in synagogues because Jews spend hours there, reading their own prayers—in the middle ages, each man did so at his own pace—and discussing religious doctrine. Books were placed on the desks during the reading, and were later stored inside the desks for the next day’s prayer and study meetings, along with the prayer shawls worn during religious services. In the Altneushul, the seats either face the bimah, or are arranged around the bimah platform; the ones we see today are neo-Gothic but reflect the original arrangement. This disposition assures that everyone is close to the bimah where the Torah portion is read each day. Members of the congregation faced each other during prayer, and that practice enhanced the sense of community. This is different from the practice in churches of that time, where the clergymen led Roman Catholics who stood one behind another and listened to a single authoritative voice.

Lighting fixtures are important in synagogues because each man must read the essential texts. In this building, the windows are small, either for customary or structural reasons or to prevent vandals from breaking large and expensive windows. Therefore, artificial lighting was needed and was provided by candlesticks but also by hanging lamps and other devices; the ones in place today are post-medieval.

Often, the bimah was made of wood, with a railing around it. The reading desk on the bimah faced the ark. In the Altneushul, the bimah is a delicate metal construction from the late fifteenth century that allows members of the congregation to easily see the reader. Both the entrance door and the pointed gable over the ark have carved decoration showing vines and fruits, though the ark is often concealed by a handsome curtain placed over it.

And the women?

So far, this essay has mentioned only men. Where were the women if they were not permitted in the main room of the synagogue? Evidence suggests that in early centuries, they were either excluded from synagogue activity or were accommodated in annexes. By the fourteenth century, a first women’s annex was built at the Altneushul with small windows that opened to the main room where the men gathered. This allowed women to hear the prayers but not to see the men or be seen by them. In the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, the congregation built additional annexes to accommodate the increasing numbers of women who elected to, or were allowed to, attend religious services. In the late middle ages, too, the high saddle roof and the brick gable were added, making the synagogue more prominent in the neighborhood.

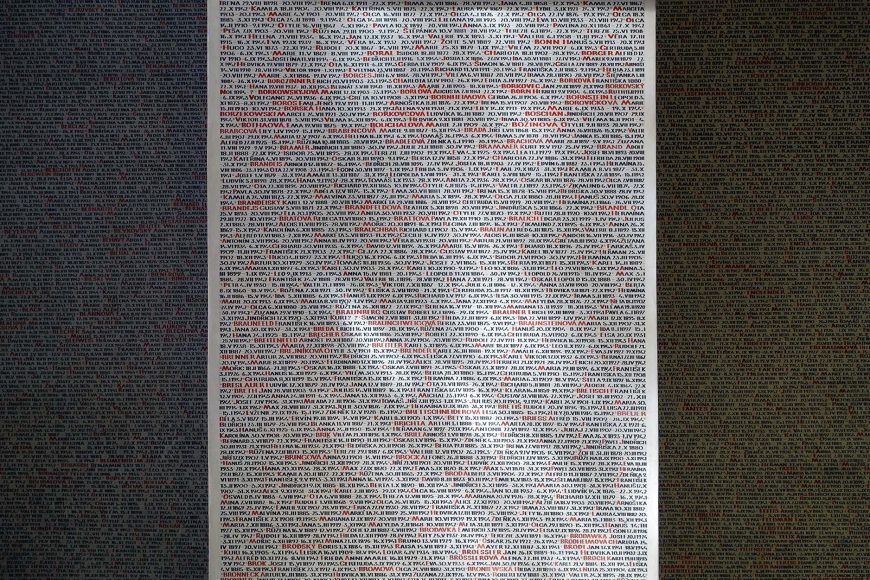

Loss and survival

Given the horrors perpetrated against European Jews during the Second World War, it may seem surprising that this building and several later synagogues in Prague have survived. The Pinkas Synagogue from the late fifteenth century is now a memorial; its walls are painted with the names of over 77,000 Czech Jews who were deported and murdered.

Perversely, the Nazis and their collaborators left these buildings standing in order to provide the setting for a museum of a vanished people that was to contain artifacts collected from the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia and material from an early twentieth-century Jewish museum. These objects are now displayed in several of the other surviving synagogues in Prague, but the Altneushul, as the oldest survivor, has been left to illustrate the appearance of an unusually distinctive medieval synagogue.

Additional Resources:

Arno Pařik, Dana Cabanova, Petr Kliment, Prague Synagogues, Prague, Jewish Museum, 2000

YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe

Carol Herselle Krinsky, Synagogues of Europe: Architecture, History, Meaning, New York, Architectural History Foundation, rev. ed., 1988

Eliyahu Hanavi Synagogue, Jobar (Syria)

by JASON GUBERMAN-PFEFFER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): A conversation with Jason Guberman-Pfeffer, Executive Director, Digital Heritage Mapping, Inc. and Coordinator, Diarna Geo-Museum and Beth Harris.