4.4: Central Africa

- Page ID

- 67044

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Central Africa

Masks, reliquaries, power figures and more.

16th - 20th century

About Central Africa

by SMARTHISTORY

Central Africa includes Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and Rwanda.

Cameroon

In the Grasslands region of northwestern Cameroon, bead embroidery is one of the most lavish arts.

19th-20th century

Ceremonial Palm Wine Vessel (Cameroon Grasslands peoples)

Of the many ritual items in a Grassfields kingdom’s royal treasury, bead-embroidered calabashes are among the most important. These containers were used exclusively by the Fon (chief) to store palm wine served on ceremonial occasions. The ritual consumption of palm wine was considered a sacred activity and reinforced the Fon’s spiritual and political power. Palm wine was also an essential component of sacrificial libations to the ancestors.

This example features a long-necked calabash attached to a tall cylindrical basketry base. The carved wood stopper has two horned animal heads facing opposing directions and a third animal head pointing upward, symbols of all-seeing powers (above). The entire assemblage is covered with cloth embroidered with strands of translucent and opaque glass beads that form intricate and colorful circular, diamond-shaped, and zigzag patterns.

These abstract geometric motifs symbolize attributes of royal power. The circular medallions surrounding the spherical body refer to the earth spider, a symbol of supernatural wisdom and communication. Because this type of spider burrows in the earth, it is believed to have the ability to unite humans, who live above the ground, with the ancestors who are buried below. Diamond-shaped motifs on the stopper and on the sides and bottom rim of the stand represent the frog, a symbol of fertility and increase. Their presence on the container conveys the idea that, with the support of many people, a peaceful and prosperous kingdom is possible.

Rulers throughout the many kingdoms in the Grassfields region of western Cameroon employed a range of art objects to assert their political, economic, and religious power. Presented publicly in lavish displays of wealth and power, many court objects were distinguished by their elaborate bead embroidery. Imported from Europe, beads were considered a luxury material whose use and distribution were controlled by the Fon. The decoration of wooden sculpture with vast quantities of brilliantly colored beads transformed utilitarian objects, such as stools, vessels, and pipes, into symbols of royal status and prestige.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Elephant Mask (Bamileke Peoples)

by DR. PERI KLEMM and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Elephant (Aka) Mask, Kuosi Society, Bamileke Peoples, Grassfields region of Cameroon, 20th century, cloth, beads, raffia, fiber, 146.7 x 52.1 x 29.2 cm (Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York)

The austere display of this powerful object masks the complexity of its original context.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Democratic Republic of the Congo

This region is home to numerous cultures and their art.

16th-20th century

Crucifix (Kongo peoples)

When Portuguese explorers first arrived at the mouth of the Zaire River in 1483, the Kongo kingdom was thriving and prosperous, with extensive commercial networks between the coast, interior, and equatorial forests to the north. Portugal and Kongo soon established a strong trading partnership. In addition to material goods, the Portuguese also brought Christianity, which was rapidly adopted by Kongo rulers and established as the state religion in the early sixteenth century by King Afonso Mvemba a Nzinga. The adoption of Christianity allowed Kongo kings to foster international alliances not only with Portuguese leaders but also with the Vatican. In response to their new faith, Kongo craftsmen began to introduce Christian iconography into their artistic repertoire.

This crucifix demonstrates how Kongo artists adapted and transformed Western Christian prototypes.

Although the general depiction of the central Christ figure with arms extended follows Western conventions, the features of the face are African. The presence of four smaller figures with clasped hands—two seated on the top edges of the cross, one at the apex, and one at the base—is a departure from standard iconography (left). These figures are more abstract and remote, in contrast to the expressionistic treatment of Christ.

Western forms like the crucifix resonated profoundly with preexisting Kongo religious practices. In Kongo belief, the cross was already regarded as a powerful emblem of spirituality and a metaphor for the cosmos. An icon of a cross within a circle, referred to as the Four Moments of the Sun, represents the four parts of the day (dawn, noon, dusk, and night) that symbolize more broadly the cyclical journey of life.

Kongo kings, having adopted Christianity as the state religion, commissioned locally made crucifixes for use as emblems of leadership and power. These crucifixes were cast with copper alloys. The use of copper, a valued import from Europe, reinforced the association with wealth and power. Although Christianity was eventually rejected by the Kongo in the seventeenth century, such works continued to be made as symbols of indigenous cosmological concepts.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Female (pwo) Mask

by DR. PERI KLEMM and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Female (pwo) mask, Chokwe peoples, Democratic Republic of Congo, early 20th century, wood, plant fiber, pigment, copper alloy, 39.1 cm high (Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington D.C.)

This mask was made and worn by men, but its purpose is to honor women who have bravely survived childbirth.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Power Figure (Nkisi Nkondi), Kongo peoples

by DR. SHAWNYA L. HARRIS and DR. PERI KLEMM

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\):

Power Figure: Male (Nkisi), 19th-mid 20th century, Kongo peoples, wood, pigment, nails, cloth, beads, shells, arrows, leather, nuts and twine, 58.8 x 26 x 25.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Speakers: Dr. Peri Klemm and Dr. Beth Harris

Divine protection

Sacred medicines and divine protection are central to the belief of the Kongo peoples (Democratic Republic of Congo). The Kongo believe that the great god, Ne Kongo, brought the first sacred medicine (or nkisi) down from heaven in an earthenware vessel set upon three stones or termite mounds.

A nkisi (plural: minkisi) is loosely translated as a “spirit” yet it is represented as a container of sacred substances which are activated by supernatural forces that can be summoned into the physical world. Visually, these minkisi can be as simple as pottery or vessels containing medicinal herbs and other elements determined to be beneficial in curing physical illness or alleviating social ills. In other instances minkisi can be represented as small bundles, shells, and carved wooden figures. Minkisi represent the ability to both ‘contain’ and ‘release’ spiritual forces which can have both positive and negative consequences on the community.

Nkisi nkondi

A fascinating example of a nkisi can be found in a power figure called nkisi nkondi (a power figure is a magical charm seemingly carved in the likeness of human being, meant to highlight its function in human affairs.). A nkisi nkondi can act as an oath taking image which is used to resolve verbal disputes or lawsuits (mambu) as well as an avenger (the term nkondi means ‘hunter’) or guardian if sorcery or any form of evil has been committed. These minkisi are wooden figures representing a human or animal such as a dog (nkisi kozo) carved under the divine authority and in consultation with an nganga or spiritual specialist who activates these figures through chants, prayers and the preparation of sacred substances which are aimed at ‘curing’ physical, social or spiritual ailments.

Insertions

Nkisi nkondi figures are highly recognizable through an accumulation of pegs, blades, nails or other sharp objects inserted into its surface. Medicinal combinations called bilongo are sometimes stored in the head of the figure but frequently in the belly of the figure which is shielded by a piece of glass, mirror or other reflective surface. The glass represents the ‘other world’ inhabited by the spirits of the dead who can peer through and see potential enemies. Elements with a variety of purposes are contained within the bilongo. Seeds may be inserted to tell a spirit to replicate itself; mpemba or white soil deposits found near cemeteries represent and enlist support from the spiritual realm. Claws may incite the spirits to grasp something while stones may activate the spirits to pelt enemies or protect one from being pelted.

The insertions are driven into the figure by the nganga and represent the mambu and the type or degree of severity of an issue can be suggested through the material itself. A peg may refer to a matter being ‘settled’ whereas a nail, deeply inserted may represent a more serious offense such as murder. Prior to insertion, opposing parties or clients often lick the blades or nails, to seal the function or purpose of the nkisi through their saliva. If an oath is broken by one of the parties or evil befalls one of them, the nkisi nkondi will become activated to carry out its mission of destruction or divine protection.

Migrations

Europeans may have encountered these objects during expeditions to the Congo as early as the 15th century. However, several of these “fetish” objects, as they were often termed, were confiscated by missionaries in the late 19th century and were destroyed as evidence of sorcery or heathenism. Nevertheless, several were collected as objects of fascination and even as an object of study of Kongo culture. Kongo traditions such as those of the nkisi nkondi have survived over the centuries and migrated to the Americas and the Caribbean via Afro-Atlantic religious practices such as vodun, Palo Monte, and macumba. In Hollywood these figures have morphed into objects of superstition such as New Orleans voodoo dolls covered with stick pins. Nonetheless, minkisi have left an indelible imprint as visually provocative figures of spiritual importance and protection.

Essay by Dr. Shawnya Harris

Additional resources:

This figure at the Detroit Institute of Arts

The sculpture at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Nkisi Nkondi on Art Through Time

Nkisi Nkondi on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

David C. Driskell, Michael D. Harris, Wyatt Macgaffey, and Sylvia H. Williams, Astonishment and power (Washington: Published for the National Museum of African Art by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993).

Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the spirit: African and Afro-American art and philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983).

Ndop Portrait of King Mishe miShyaang maMbul (Kuba peoples)

In all world cultures, artists honor remarkable leaders by creating lasting works of art in their honor. Historical leaders in the West, like Charlemagne and Alexander the Great were celebrated for their accomplishments during their lifetime and remembered through many works of art created to preserve their legacy. During the first half of the eighteenth century, the Kuba King Mishe miShyaang maMbul was celebrated throughout his kingdom for his generosity and for the great number of his loyal subjects. He was even the recipient of his own praise song. At the height of his reign in 1710, he commissioned an idealized portrait-statue called an ndop. With the commission of his ndop, Mishe miShyaang maMbul recorded his reign for posterity and solidified his accomplishments amongst the pantheon of his predecessors. The ndop that portrayed his likeness was eventually purchased by the Brooklyn Museum in 1961 and has been on view at the museum since that time. It was first collected in 1909 by a colonial minister in what was then the Belgian Congo, the European country’s colony.

Why are Mishe miShyaang maMbul and others commemorated in the arts of Africa largely unknown to us? Unlike in Euro-American contexts, history in Sub-Saharan Africa was not written down by members of cultural communities until colonialism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Instead of written records, oral narrative was the primary method for collective and personal histories to be passed down from one generation to the next. As these spoken histories were passed down, they were changed and adapted to reflect their times. The changing nature of oral narrative is like a highly complex game of telephone, where the words can be changed and often only the spirit of the original meaning is preserved.

Before being purchased by Western collectors and museums, African sculptures served as important historical markers within their communities. The ndop sculptural record helps freeze a moment in time that would otherwise be transformed during its transmission from generation to generation. When we look at these sculptures in museums, it is important to remember that they were created about, and for, individuals. Since information and history was transferred orally in Africa, sculptural traditions like the ndop can help us gain insight into information about historical individuals and their cultural ideals.

The Kuba Artist

The Kuba live in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the southern fringes of the equatorial forest in an area bounded by two rivers called the Kasai and Sankuru. Over a period of three centuries of movement and exchange beginning in the 17th century, this loose confederacy of people formed into a durable kingdom. Since that time, the name “Kuba” largely refers to nineteen unique but related ethnic groups, all of which acknowledge the leadership of the same leader (nyim).

The Kuba are renowned for a dynamic artistic legacy across media. Historically, Kuba artists were professional woodcarvers, blacksmiths, and weavers who worked exclusively for the nyim. Kuba artists learned their art by becoming apprentices to others who were well-known and accomplished in their community. Similar to art traditions in other world cultures, the apprentices imitated or copied early pieces from their teachers until they were skilled enough to develop their own designs. Although the names of individual artists were not written down—and are not known to us today—artists were sought after by name and were important to the Kuba royal court and beyond.

Ndop Sculpture

The ndop statues might be the the most revered of all Kuba art forms. The ndop (literally meaning “statue”) are a genre of figurative wood sculpture that portrays important Kuba leaders throughout the eighteenth to twentieth centuries. Art historians believe that there are seven ndop statues of historical significance in Western museums. These seven are significant because the lives of the nyim they portray were celebrated in oral histories that were recorded and written down by early European visitors, so we know the most about them.

You can travel to the British Museum in England or the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium to see ndop. Ndop sculptures that are on view at the British Museum were brought to Europe from Africa by Hungarian ethnographer Emil Torday. Torday and other early visitors to the Kuba court documented oral traditions related to artwork. Art historians have since tried to reconstruct and sort out these early accounts; they use the sculptures themselves to interpret precolonial Kuba history.

Ndop sculpture have rounded contours creating forms that define the head, shoulders and stomach, and also feature a defined collarbone. While the relative naturalism may appear to have been informed by an artist’s one-to-one observation of the nyim, ndop sculptures aren’t exact likenesses; they are not actually created from direct observation. Instead, cultural conventions and visual precedents guide the artists in making the sculpture. The expression on the face, the position of the body, and the regalia were meant to faithfully represent the ideal of a king—but not an individual King. For example, the facial features of each statue follow sculpting conventions and do not represent features of a specific individual. All figures are sculpted using a one-to-three proportion—the head of the statue was sculpted to be one third the size of the total statue. Kuba artists emphasized the head because it was considered to be the seat of intelligence, a valued ideal.

How are we able to identify each ndop, then? There are specific attributes that link each ndop to named individuals. All ndop sculpture would feature a geometric motif and an emblem (ibol), chosen by the nyim when he was installed as a leader and commissioned his ndop. The geometric motif pattern and the ibol served as identifying symbols of his reign and was sculpted in prominent relief on the front of each base. The ibol is a signifier that gives the ndop its particular identity, making it clear who the sculpture portrays and what reign it represents. A drum with a severed hand is the ibol for Mishe miShyaang maMbul’s reign, and that helps us identify the sculpture as his likeness.

Other styles or conventions that were followed by sculptors of Ndop can be found in royal regalia such as belts, armbands, bracelets, shoulder ornaments, and a unique projecting headdress, called a shody. The arms of each ndop extend vertically at either side of the torso, with the left hand grasping the handle of a ceremonial knife (ikul) and the right hand resting on the knee. Artists decorated the surface of the sculpture by carving representations of what was conventionally worn; the finely chiseled details correspond to objects that represent the prerogative and prestige of the nyim.

The ndop of Mishe miShyaang maMbul is part of a larger genre of figurative wood sculpture in Kuba art. These sculptures were commissioned by Kuba leaders or nyim to preserve their accomplishments for posterity. Because transmission of knowledge in this part of Africa is through oral narrative, names and histories of the past are often lost. The ndop sculptures serve as important markers of cultural ideals. They also reveal a chronological lineage through their visual signifiers.

Additional Reading

Binkley, David A. and Patricia Darish. Kuba. Milan: 5 Continents Press, 2010.

LaGamma, Alisa. Heroic Africans: Legendary Leaders, Iconic Sculptures. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.

Siegmann, William and Joseph Adande. African Art: A Century At The Brooklyn Museum. New York: Prestel, 2009.

Vansina, Jan. “Recording the Oral History of the Bakuba.” Journal of African History 1:1, 1960, 43 – 61.

Lukasa (Memory Board) (Luba peoples)

by JULIET MOSS

Performing history

While Europeans may open a history book to learn about their past, in the Luba Kingdom of the Democratic Republic of Congo, history was traditionally performed—not read. In fact, Luba royal history is not chronological and static as Westerners learn it. Rather, it is a dynamic oral narrative which reinforces the foundations upon which Luba kingship is established and supports the current leadership. This history is also used to interpret and judge contemporary situations.

Special objects known as lukasa (memory boards) are used by experts in the oral retelling of history in Luba culture. The recounting of the past is performative and includes dance and song. The master who has the skill and knowledge to read the lukasa will utilize it as a mnemonic device, touching and feeling the beads, shells, and pegs to recount history and solve current problems.

Luba Kingdom

The Luba Kingdom of the Democratic Republic of Congo was a very powerful and influential presence from the sixteenth to the early twentieth centuries in central Africa. Their art highlights the roles that objects played in granting the holders the authority of kingship and royal power.

The Luba people are one of the Bantu peoples of Central Africa and the largest ethnic group in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Kingdom of the Luba arose in the Upemba Depression (a large marshy area comprising some fifty lakes) in what is now the southern Democratic Republic of Congo. The Luba had access to a wealth of natural resources including gold, ivory, and copper, but they also produced and traded a variety of goods such as pottery and wooden sculpture.

Lukasa

For the Luba people, kingship is sacred, and the elite Mbudye Society (whose members are considered “men of memory,” and who have extensive religious training) use the lukasa to recount history in the context of spiritual rituals. Diviners (who have the power to predict the future) can also read the lukasa.

Each lukasa is different but small enough to hold in the left hand. The board is “read” by touching its surface with the right forefinger. The tactile qualities are apparent. The lukasa illustrated here is one of the oldest known examples, with carved geometric designs on the back and sides, and complex clusters of beads of various sizes whose colors have faded over time. The board is narrower at the center making it easy to hold.

The lukasa is typically arranged with large beads surrounded by smaller beads or a line of beads, the configuration of which dictates certain kinds of information. This information can be interpreted in a variety of ways and the expert might change his manner of delivery and his reading based upon his audience and assignment. The most important function of the lukasa was to serve as a memory aid that describes the myths surrounding the origins of the Luba empire, including recitation of the names of the royal Luba line.

Buli Master, possibly Ngongo ya Chintu, Prestige Stool: Female Caryatid (Luba or Hemba peoples)

Sculpted seats are among the most important insignia of office used exclusively by Luba rulers, including kings, chiefs, and the heads of clans or lineages. A royal stool is believed to serve as a receptacle for a ruler’s spirit. It therefore holds great symbolic value as the repository and wellspring of sacred kingship. Such seats, part of the ensemble of regalia that constitutes a Luba treasury, are an integral part of the investiture ceremony establishing a ruler’s political authority. Except for these rare ceremonial occasions, the royal stool was wrapped in cloth and safeguarded by a specially designated official.

This figurative example is supported by a standing female figure whose high status is indicated by her elaborate four-lobed coiffure and intricate raised scarification patterns on her torso, both front and back. The depiction of women on royal stools acknowledges their important political and symbolic roles in Luba society. Historically, female royals were often married to chiefs in outlying areas, helping to expand and unify the kingdom. Because the Luba trace succession and inheritance through the female line, such marriages established important bonds of kinship and allegiance. The imagery of the female supporting the stool symbolizes the fact that the chief or king inherits the right to rule through his female ancestors. Luba leaders owned a series of items of regalia depicting female figures which referred to the female body as a receptacle for the spiritual power of divine kingships.

This royal ceremonial stool was created by an artist known as the Buli Master, celebrated for the distinctive formal structure and emotional appeal of his sculptures. His extraordinary artistic legacy is a corpus of about twenty stylistically related works, all demonstrating a unique expressionism. Lacking the youthful idealism more commonly seen in African sculpture, this figure has an elongated face with prominent cheekbones, arching brows, half-closed eyes set in sunken sockets, a high rounded forehead, and pursed lips. Her body is small and stooped, suggesting that the seat weighs heavily upon her. These features create a sense of sadness or suffering not typically seen in African sculpture, which tends to be fairly emotionless.

The Buli Master, named after a village in the eastern part of Democratic Republic of Congo where some of his works were acquired, is believed to have been active in the mid- to late nineteenth century. The sculptor has created a dynamic formal composition, building in volume and complexity from the base to the top. Her large feet, barely raised from the base of the stool, provide the foundation for the stool’s vertical support formed by her short sturdy legs, torso, and large oval head. The seat rests upon her coiffure and the tips of her fingers. The sense that she bears a heavy burden is reinforced by exaggerated flattened hands.

All royal stools are conceived of as replicas of an original seat of office given to the Luba king Kalala Ilunga. The Luba kingdom was said to have been founded by Kalala Ilunga, a heroic prince who overthrew his despotic uncle to establish a new dynasty of divine rulers. Leaders of the various Luba chiefdoms in the area have historically traced their descent from this founding ruler. Their exalted position within this sacred line of succession is expressed materially by the possession of royal insignia designed to bolster chiefly authority.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This work on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Mary Nooter Roberts, Luba Art and Divination on Art and Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

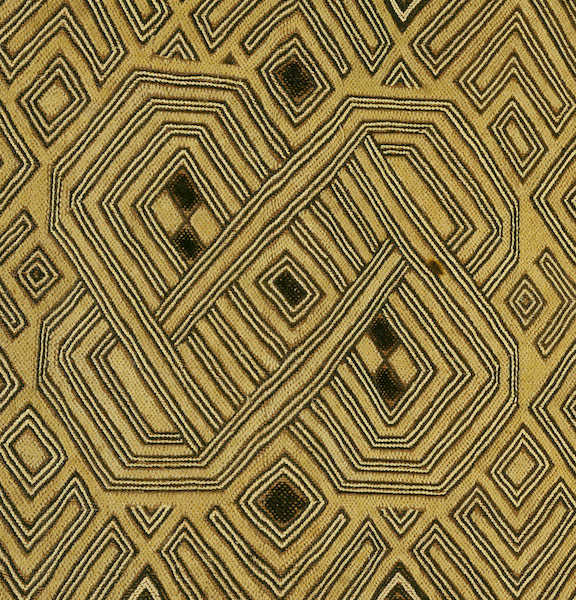

Double Prestige Panel (Kuba peoples)

This double panel of raffia cloth with cut-pile embroidery was created to serve as a prestige item in Kuba society. The Kuba kingdom has a complex political structure composed of independent chiefdoms under the central authority of a king. It was founded in the early seventeenth century by Shyaam a-Mbul a Ngoong, a ruler who brought together some seventeen different ethnic groups into a unified polity. Shyaam is recalled as a dynamic and innovative leader who introduced a number of important Kuba artistic traditions, including lavish woven and embroidered textiles made of raffia. In fact, the Kuba founding ruler is said to have identified so closely with the patronage of these textiles that he adopted the term for raffia palm, shyaam, as his name.

In this complex composition, each panel features a large central interlacing motif against a diamond-patterned background. The dense patterns have been embroidered with strands of dyed raffia fiber that are cut close to the surface, creating a soft, velvety texture. Varying in both tone and texture, the patterns project dramatically from the gold field.

The preparation, production, and design of Kuba raffia textiles require the collaborative efforts of both men and women. Men are responsible for cultivating raffia palm trees and collecting the outer layers of the fronds, which yield fiber strands. They weave these strands on a vertical heddle loom into panels of cloth. Individual woven units, known as mbala, are softened and refined to a linen-like texture by pounding. These flat-woven panels may then be decorated and stitched together to form garments. Women assemble and decorate their own skirts, which can be up to nine yards in length. Men fashion their skirts, which can be of greater length and have a border of raffia tufts. Both genders employ a range of decorative processes, including dying, appliqué, embroidery, and patchwork, although some distinctive techniques, such as openwork and cut- pile, are practiced only by women. The completed garments are worn differently: women wrap the skirt around their bodies, while men gather the cloth around their hips, secured by a belt with the top folded over.

Some raffia cloth, like this panel, was not fashioned into garments, but was displayed instead as prestige items. In the past, individual panels of raffia textiles were used as objects of exchange in financial, legal, and even marital transactions. They were also displayed and offered as memorial gifts during funerals, as an indication of the deceased’s importance as well as the generosity of the surviving family members. Today, despite the availability of machine- made cotton cloth, raffia textiles are still regarded as the only kind of garment appropriate to adorn the body of the deceased. An important individual may be buried dressed in multiple layers of raffia skirts, often family treasures passed down through generations.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The work on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Kingdoms of the Savanna: The Kuba Kingdom

Kuba Peoples on Art and Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Figurative Harp (Domu) (Mangbetu peoples)

In northern Democratic Republic of Congo, the Mangbetu peoples established an influential centralized kingdom that reached its apex of power during the second half of the nineteenth century. Mangbetu aristocrats surrounded themselves with a variety of finely crafted utilitarian objects, including boxes, stools, weapons, and musical instruments. The opulence of the kingdom captured the attention of European visitors to the region, who described Mangbetu court life and its artistic traditions in glowing terms.

This musical instrument, with freestanding strings that rise in a horizontal plane from its belly to neck, is a harp. The curved neck ends in a finely carved head with partially open mouth, as if in song. The wooden sound box is covered with carefully stitched animal hide. When playing the harp, a musician sat with the sound box on his lap and the neck pointing away from him. He held the neck with his left hand and plucked the strings with both. The harp player adjusted the tone of each string by turning the tuning pegs set in the harp’s neck. Harp players performed for the entertainment of community groups and, as they played, sang about events in their travels and heroic deeds of the past.

The presence of a carved head on this harp may reflect an African response to Western aesthetic taste and patronage. In the colonial period, Europeans began to commission sculpture from local Mangbetu artists, expanding the demand for such works. Fascinated by the bound and elongated heads once common among the Mangbetu (fig. 9), European patrons encouraged artists to include human forms on objects that were previously nonfigurative. Although popular as gifts to visiting foreign dignitaries, these figurative objects were rarely commissioned for local use and their production eventually ceased.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Gabon

The art by people in this region is of immense spiritual significance.

19th-20th century

Kota reliquary (mbulu ngulu)

by DR. KATHRYN WYSOCKI GUNSCH and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Kota reliquary figure (mbulu ngulu), late 19th to early 20th century, Gabon, wood, copper, brass, and bone, 59.69 cm high (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

These reliquary figures helped a nomadic society to honor their loved ones after death.

Additional resources

This sculpture at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Female Figure from a Reliquary Ensemble (Fang peoples)

The Fang peoples of Gabon believed that ancestral relics held great spiritual power. Byeri was a Fang association devoted to the veneration of lineage ancestors and founders, leaders, and fertile women who made significant contributions to society during their lifetime. After death, their relics, particularly the skull, were conserved in cylindrical bark containers and guarded by carved wooden heads or figures mounted atop the receptacles.

The lustrous black surface of this carved female figure still glistens from repeated applications of palm oil used for ritual purification. The sculptor shaped this figure to illustrate the ability to hold opposites in balance, a quality admired by the Fang. He juxtaposed the large head of an infant with the developed body of an adult. The static pose and expressionless face contrast with the palpable tension of the bulging muscles and the projecting forms of the arms, legs, and breasts. These reliquary sculptures may be male or female and are not considered portraits of the deceased. They were often decorated with gifts of jewelry or feathers and received ritual offerings of libations, such as palm oil.

On the occasion of initiation into Byeri, the figures were removed from their containers and manipulated like puppets in performances that dramatized the raising of the dead for didactic purposes. During the early twentieth century, Fang reliquary sculpture began to be acquired by Western collectors, who admired the inspired interpretation of the human form. This particular work was formerly in the collections of two well- known modernist artists, the painter André Derain and the sculptor Jacob Epstein.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Female Reliquary Guardian Figure (Fang peoples)—video

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. PERI KLEMM

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Reliquary Guardian Figure (Eyema-o-Byeri), Gabon, Fang peoples, mid 18th to mid 19th century, wood and iron, 58.4 cm high (Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York)

These figures look calm and contemplative, but also display real strength and vitality in their muscular forms.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning: