3.4: Later period

- Page ID

- 67038

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The later period

The Blue Mosque, the Ardabil Carpet, and the Taj Mahal all date to this important period.

c. 1517 - 1924 C.E.

Arts of the Islamic world: The later period

What does the Taj Mahal have to do with the Tamerlane? What do Persian carpets have to do with Turkish tiles? Quite a bit, as it turns out. By the fourteenth century, Islam had spread as far East as India and Islamic rulers had solidified their power by establishing prosperous cities and a robust trade in decorative arts along the all-important Silk Road. This is a complex period with competing and overlapping cultures and empires. Read below for an introduction to the later Islamic dynasties.

Ottoman (1300-1924)

At its earliest stages, the Ottoman state was little more than a group formed as a result of the dissolution of the Anatolian Seljuq sultanate. However, in 1453, the Ottomans captured the great Byzantine capital, Constantinople, and in 1517, they defeated the Mamluks and took control of the most significant state in the Islamic world.

While the Ottomans ruled for many centuries, the height of the empire’s cultural and economic prosperity was achieved during Süleyman the Magnificent’s reign (r. 1520-1566), a period often referred to as the Ottoman’s ‘golden age.’ In addition to large-scale architectural projects, the decorative arts flourished, chief among them, ceramics, particularly tiles. Iznik tiles, named for the city in Anatolia where they were produced, developed a trademark style of curling vines and flowers rendered in beautiful shades of blue and turquoise. These designs were informed by the blue and white floral patterns found in Chinese porcelain—similar to earlier Mamluk tiles, and Timurid art to the East. In addition to Iznik, other artistic hubs developed, such as Bursa, known for its silks, and Cairo for its carpets. The capital, Istanbul (formerly Constantinople), became a great center for all matters of cultural importance from manuscript illumination to architecture.

The architecture of the period, both sacred and secular, incorporates these decorative arts, from the dazzling blue tiles and monumental calligraphy that adorn the walls of Topkapi Palace (begun 1459) to the carpets that line the floors of the Süleymaniye Mosque (1550-1558). Ottoman mosque architecture itself is marked by the use of domes, widely used earlier in Byzantium, and towering minarets. The Byzantine influence draws primarily from Hagia Sophia, a former church that was converted into a mosque (and is now a museum).

Timurid (1369-1502)

This powerful Central Asian dynasty was named for its founder, Tamerlane (ruled 1370-1405), which is derived from Timur the Lame. Despite his rather pathetic epithet, he claimed to be a descendent of Genghis Khan and demonstrated some of his supposed ancestor’s ruthlessness in conquering neighboring territories.

After establishing a vast empire, Timur developed a monumental architecture befitting his power, and sought to make Samarkand the “pearl of the world.” Because the capital was situated at a major crossroads of the Silk Road (the crucial trade route linking the Middle East, Central Asia, and China), and because Timur had conquered so widely, the Timurids acquired a myriad of artisans and craftspeople from distinct artistic traditions. The resulting style synthesized aesthetic and design principles from as far away as India (then Hindustan) and the lands in between.

The result can be seen in cities filled with buildings created on a lavish scale that exhibited tall, bulbous domes and the finest ceramic tiles. The structures and even the cities themselves are often described foremost by the overwhelming use of blues and golds. While the Timurid dynasty itself was short-lived, its legacy survives not only in the grand architecture that it left behind but in its descendants who went on to play significant roles in the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires.

Safavid (1502-1736)

The Safavids, a group with roots in the Sufic tradition (a mystical branch of Islam), came to power in Persia, modern-day Iran and Azerbaijan. In 1501 the Safavid rulers declared Shi’a Islam as its state religion; and in just ten years the empire came to include all of Iran.

The art of manuscript illumination was highly prized in the Safavid courts, and royal patrons made many large-scale commissions. Perhaps the most notable of these is the Shahnama (or ‘Book of Kings,’ a compilation of stories about earlier rulers of Iran) from the 1520s. While painting in this context did not have the same prominent and longstanding tradition as it does in Western art, the illustrations exhibit masterful workmanship and an incredible attention to detail.

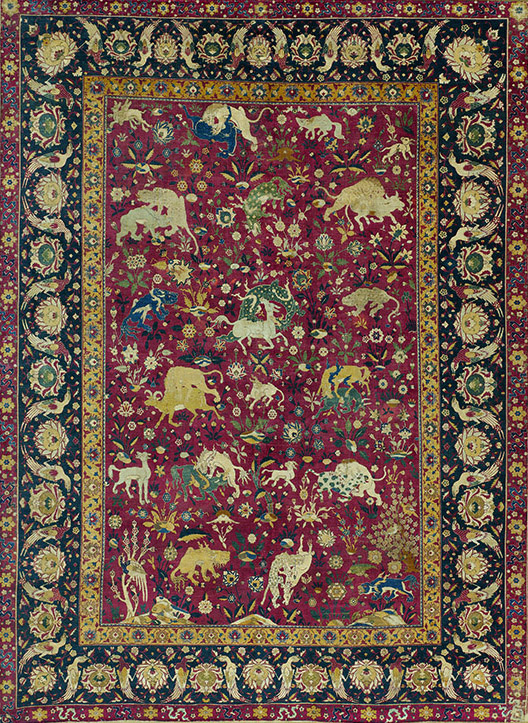

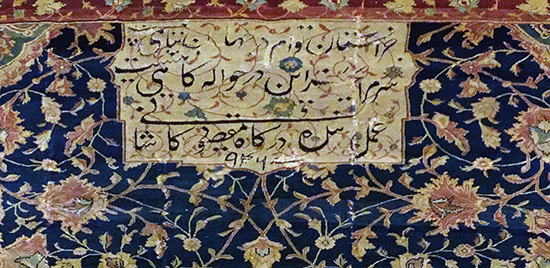

Trade in carpets was also important, and even today, people understand the appeal of Persian carpets. These large-scale, high-quality pieces were created as luxurious furnishings for royal courts. The most famous—perhaps of all time—is a pair known as the Ardabil Carpets, created in 1539-1540. The carpets were nearly identical, perfectly symmetrical and enormous. Every inch of space was filled with flowers, scrolling vines, and medallions.

The empire began to struggle financially and militarily until the rule of Shah Abbas (r. 1587-1629). He moved the capital to Isfahan where he built a magnificent new city and established state workshops for textiles, which, along with silk and other goods, were increasingly exported to Europe. The mosque architecture made use of earlier Persian elements, like the four-iwan plan and building materials of brick and glazed tiles reminiscent of Timurid architecture, with its blues and greens and bulbous domes. Even in such far-removed lands, the connections between these dynasties are evident in the art they created.

Mughal (1526-1858)

Though Islam had been introduced in India centuries before, the Mughals were responsible for some of the greatest works of art produced in the canons of both Indian and Islamic art. The empire established itself when Babur, himself a Timurid prince of Turkish and Central Asian descent, came to Hindustan and defeated the existing Islamic sultanate in Delhi.

Tracing their roots to Central Asia, the Mughals produced art, music and poetry that was highly influenced by Persian and Central Asian aesthetics. This is evident in the style and importance given to miniature paintings, created to illustrate manuscripts. The most grandiose of these was the Akbarnama, created to record the conquests of Akbar, widely regarded as the greatest Mughal emperor. The art and architecture created during his reign demonstrate a synthesis of indigenous Indian temple architecture with structural and design elements derived from Islamic sources farther West. The Mughals developed a unique architectural style which, in the years after Akbar’s reign, began to feature scalloped arches and stylized floral designs in white marble. The most famous example is the Taj Mahal, constructed by Shah Jahan from 1632-1653.

The Mughal dynasty left a lasting mark on the landscape of India, and remained in power until the British completed their conquest of India in the nineteenth century.

Although historians generally agree that the major Islamic dynasties end in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Islamic art and culture have continued to flourish. Muslim artists and Muslim countries are still producing art. Some art historians consider such work as simply modern or contemporary art while others see it within the continuity of Islamic art.

Additional resources:

The Art of the Ottomans before 1600 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

The Art of the Safavids before 1600 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

The Art of the Mughals before 1600 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Hagia Sophia as a mosque

by DR. ELIZABETH MACAULAY-LEWIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles (architects), Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, 532-37

This video focuses on Hagia Sophia after the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans in 1453.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Mimar Sinan

Mimar Sinan, Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul

by DR. ELIZABETH MACAULAY-LEWIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Mimar Sinan, Süleymaniye Mosque, completed 1558, Istanbul, Turkey

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Mimar Sinan, Mosque of Selim II, Edirne

by DR. ELIZABETH MACAULAY-LEWIS

Elegant stacked domes, reaching to the heavens, and towering, slender pencil minarets characterize Ottoman mosque architecture. Few mosques, however, are as visually stunning and architecturally significant as the Selimiye Complex in Edirne built by the greatest of all Ottoman architects, if not one of the greatest of architects to ever live: Sinan.

Edirne

Selimiye complex was located in Edirne rather than the capital, Istanbul. It was built by the Sultan Selim II, the son of Süleyman the Magnificent, between 1568 and 1574. Edirne was one of Selim II’s favorite cities. He was stationed here as a prince when his father campaigned in Persia in 1548 and he enjoyed hunting on the outskirts of the city.

Edirne was selected not only because of Selim II’s fondness of the city, but also for its historical and geographic significance. Located in the Balkans, within the European lands of the Ottoman Empire, Edirne had been a capital of the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century before Istanbul and was effectively the second city of the Empire through the 17th century.

Edirne was the first major city that Europeans traveling to the Ottoman Empire reached—so building a large complex here offered the Sultan an opportunity to use architecture to impress the Ottoman Empire’s greatness upon visitors. Furthermore because Edirne was not Istanbul, whose Golden Horn and many hills were already home to monumental mosque complexes, it also offered an opportunity to build a mosque that would dominate the city. Built in an area of the city once known as Kavak Meydani, the modern designs of the Selimiye complex overshadowed Edirne’s more traditional architecture.

The complex is huge. It measures 190 x 130 meters (or more than the length of two football fields) and is composed of a mosque, two symmetrical square madrasas (one of which served as a college for studying the hadiths, or traditions of the Prophet Muhammad), and there was a row of shops (arasta) and a school for learning the recitation of the Quran located to the west and added during the reign of Sultan Murad III, whose rule followed Selim II. It is likely these additions were planned by Sinan.

The mosque

The mosque’s nearly square prayer hall is approached through a porticoed courtyard, making the central block of the complex rectangular. The approach to the north façade of the mosque (above) is dramatic: the aligned gates of the outer precinct wall and forecourt focus the eye upwards toward the dome, which could also been seen from a distance.

The ethereal dome seems weightless as it floats above the prayer hall. All of the architectural features are subordinated to this grand dome. The dome rests on eight muqarnas-corbelled squinches that are in turn supported by eight large piers.

Muqarnas are the faceted decorative forms that alternately protrude and recess and that are commonly used in Islamic architecture to bridge a point of transition—in this case, the broad base of the dome above and the slender piers below. Note that the muqarnas steps outward it rises, creating a corbelled effect, and allowing for a more open space below. The squinches are the architectural support, decorated by the muqarnas, transition from the dome down to the eight piers.

They allow the round base of the dome to join octagon formed by the piers. A complex system of exterior buttresses support the east and west piers and do most of the work to hold up the massive weight of the dome. These buttresses are artfully hidden among the exterior porticos and galleries. In the interior, galleries fill the spaces in between the walls and the piers. The Qibla wall (the wall that faces Mecca) projects outward further emphasizing the openness the interior space. Sinan completely departed from the screen walls and supporting half-domes he had employed in his earlier design for the Süleymaniye Complex in Istanbul.

The placement of the muzzin’s platform (müezzin mahfili), under the center of the dome is very unusual. From this platform, the muzzins who lead prayers, chant to the congregation. Gülru Necipoğlu, a leading Ottoman art historian, has compared its placement to that of a church’s altar or ambo, a raised stand for biblical readings in a church. She notes that while this innovation disrupts the space below the dome, it reflects Sinan’s interest in surpassing Christian architecture. The position of the platform also creates a vertical alignment of square, octagon, and circle, using geometry to refer to the earthly and heavenly spheres.

The original appearance of the interior’s decoration was different from what we see today. The interior has been repainted through the centuries and was extensively restored in the 20th century. However, the brilliant, polychrome Iznik tiles, the epitome of Ottoman decoration, and whose motifs include iconography such as saz leaves and Chinese clouds, remain largely untouched since the 16th century.

Influences

The mosque’s epigraphic program—its inscriptions, was developed after the devastating defeat that the Ottoman fleet suffered at Lepanto in 1571 against the navies of the Christian Holy League. This loss prevented further Ottoman expansion along the European coast of the Mediterranean. The mosque’s inscriptions focus on a central difference between Islam and Christianity—mainly that Allah (God) is indivisible and that the prophet Muhammad is God’s human messenger. Certain passages from the Hadiths were included to emphasized Muhammad’s position as a messenger both and intercessor.

The unified, open plan of the mosque is matched by the artful stacking of volumes on the exterior. Unlike many other earlier Ottoman mosques and the early Byzantine church, Hagia Sophia (then converted to a mosque and now a museum), the exterior is clearly not an artistic afterthought but rather an elegant, architectural shell vital to the overall composition. The placement of the pencil minarets at the four corners of the prayer hall focus attention on the volume of the Dome. Polychrome exterior is composed of stone mixed with brick that compliments the geometric volumes that define the exterior forms of the building.

The dome’s octagonal shape was probably influenced by the tomb of Öljeitü in Soltaniyeh, which Sinan had seen while on Süleyman’s Baghdad campaign. The tomb had a large octagonal dome of 25 meters, which at one time was surrounded by eight turrets, which we can see echoed at Edirne. Sinan’s dome, at just over 31 meters, is larger than Hagia Sophia’s. The architect had wanted to disprove claims that no architect could match Hagia Sophia. Selim II funded his project with booty taken from the Ottoman campaign against Cyprus, a Christian island. Sinan sought to build a monument for the Sultan that expressed Islam’s triumph. His achievement—building a mosque that surpassed Hagia Sophia—was recognized as soon as the mosque was complete. Evliya Çelebi, a 17th century writer who traveled extensively across the Ottoman Empire, praised the mosque in his ten-volume Seyahtname, (or “Travelogue”).

Mimar Sinan was a product of the Devşirme, a practice of the Ottoman authorities from the fourteenth through early eighteenth century, where young, talented, Christian men were taken from their families to serve in the military or the civil service. Sinan was one such boy; he served during Süleyman’s campaigns, learning engineering and siege warfare before becoming one of history’s great architects.

Additional resources:

Art of the Ottomans after 1600

3D tour of the Selimiye Complex

Gülru Necipoğlu, The age of Sinan: architectural culture in the Ottoman Empire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005)

Mimar Sinan, Rüstem Pasha Mosque, Istanbul

by DR. ELIZABETH MACAULAY-LEWIS and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Mimar Sinan, Rüstem Pasha Mosque, Istanbul, 1561-63

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Tughra (Official Signature) of Sultan Süleiman the Magnificent from Istanbul

by THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Tughra (Official Signature) of Sultan Süleiman the Magnificent, ca. 1555–60, ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 25 x 30″ / 63.5 x 76.2 cm) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Raised to a high art form within the Ottoman chancery, the tughra served as the official seal of the sultan. Affixed to every royal edict, this stylized signature is an intricate calligraphic composition comprising the name of the reigning sultan, his father’s name, his title, and the phrase “the eternally victorious.” Its bold, gestural line contrasts with the delicate swirling vine-scroll illumination used to ornament the seal.

Additional resources:

The Blue Mosque (Sultan Ahmet Camii)

A young sultan

Imagine yourself as a young sultan in charge of an empire spanning parts of three continents—Asia, Europe, and Africa—your ancestors brought together through conquests. You are 13 years old and are enthroned in the capital city, Istanbul. You are confronted with the legacy of great rulers before you such as Suleiman the Magnificent and Mehmet the Conqueror. And yet, you are neither a renowned warrior nor an able administrator. How do you leave your mark on the fabric of the city that your forebears coveted and conquered? You commission one of the finest mosques in the heart of the imperial city.

The Sultan Ahmet Mosque, popularly known as the Blue Mosque, was completed in 1617 just prior to the untimely death of its then 27-year old eponymous patron, Sultan Ahmet I. The mosque dominates Istanbul’s majestic skyline with its elegant composition of ascending domes and six slender soaring minarets. Although considered one of the last classical Ottoman structures, the incorporation of new architectural and decorative elements in the mosque’s building program and its symbolic placement at the imperial center of the city point to a departure from the classical tradition innovated under the famous 16th-century master architect, Mimar Sinan.

A symbolic location

The mosque’s site is politically charged. Unlike other Ottoman imperial mosques, which were placed farther away from the city center to encourage urban development and to take advantage of Istanbul’s hilly topography, the Sultan Ahmet mosque is nestled in between the Hagia Sophia and the Byzantine Hippodrome near the Ottoman royal residence, Topkapı Palace. In fact, the choice of location caused some consternation since it required the demolition of quite a few established palaces owned by Ottoman ministers. But prestige outweighed the enormous cost in coin and real estate. Constructing large mosque complexes for the benefit of the public was part of the imperial tradition denoting a pious and benevolent ruler. Placing the mosque adjacent to the Hagia Sophia also signified the triumph of an Islamic monument over a converted Christian church, a matter of great concern even 150 years after the Ottoman conquest of Istanbul in 1453.

The rivalry between the two monuments is difficult to ignore as you alight from the tram and walk towards them today. Both buildings overwhelm with their massive proportions and their individual claims on the city’s history. But the Sultan Ahmet mosque is distinct from the 6th-century church. The mosque features two main sections: a large unified prayer hall crowned by the main dome and an equally spacious courtyard. In contrast to earlier imperial mosques in Istanbul, the monotony of the exterior stone walls is relieved through numerous windows and a blind arcade. Huge elevated and recessed entrances penetrate three sides of its precinct to provide access to the sacred core. The courtyard’s inner frame is a domed arcade, which is uniform on all sides except for the prayer hall entrance where the arches expand.

Inside, the central dome rests on delicate pendentives (triangular segments of a spherical surface) with its weight supported on four massive fluted columns. In order to extend the prayer space beyond the span of the central dome, a series of half-domes cascade outwards from the center to ultimately join the exterior walls of the mosque. Of the six minarets (towers traditionally built for the call to prayer), four are positioned on the corners of the mosque’s prayer hall while the other two flank the external corners of the courtyard. Each of these “pencil” minarets has a series of balconies adorning its lean form.

Six minarets were unusual even for an imperial mosque—they implied equality with the multi-minareted mosques of Mecca leading to considerable resistance from the local population. The solution? Legend has it that in an attempt at appeasement, a seventh minaret was added to the mosque in Mecca, proving its primacy over any imperial mosque in Istanbul or elsewhere. But evidence to support this claim is thin since some believe the seventh minaret already existed prior to the Blue Mosque’s construction while others cite a much later date for the seventh minaret’s addition.

The interior

The prayer hall itself is punctuated with several architectural features including the sultan’s platform and an arcaded gallery running along the interior walls except on the quibla wall facing Mecca. A carved marble niche set into the center of this wall guides the faithful to the correct direction for prayer. To its right is a tall and thin marble pulpit (mimbar) capped with an ornamental turret.

Tilework and stained glass

Upper sections of the mosque are painted in geometric bands and organic medallions of bright reds and blues, but much of this is not original. Rather, the careful choreography of more than 20,000 Iznik tiles rise from the mid-sections of the mosque and dazzle the visitor with their brilliant blue, green, and turquoise hues, and lend the mosque its popular sobriquet.

Traditional motifs on the tiles such as cypress trees, tulips, roses, and fruits evoke visions of a bountiful paradise. Sultan Ahmet requisitioned these specifically for the building. The lavish use of tile decoration on the interior was a first in Imperial Ottoman mosque architecture. The intensity of the tiles is accentuated by the play of natural light from more than 200 windows that pierce the drums of the central dome, each of the half-domes, and the side walls. These windows originally contained Venetian stained glass.

Legacy

The Sultan Ahmet Mosque is particularly remarkable in that it was conceived and built during a time of relative decline. In the past, grand mosques were constructed as markers of prosperity and political strength. Even though Ahmet I showed promise when he first assumed the throne, he is now seen as a weak and incompetent sultan. A few short years into his reign, he conceded autonomy to the Habsburg rulers and freed them from paying tribute. His inability to control and sustain a stable administration inaugurated an era of malaise and contributed to the reversal of Ottoman fortunes. In spite of these troubles, his legacy remains cemented in the breathtaking beauty of the Blue Mosque.

Additional resources:

Sultanahmet Mosque Association

Freely, John. Istanbul: The Imperial City. London: Viking, 1996.

Goodwin, Godfrey. A History of Ottoman Architecture. 1971. Reprint, New York: Thames & Hudson, 1987.

Kafescioğlu, Çiğdem. Constantinopolis/Istanbul: Cultural Encounter, Imperial Vision, and the Construction of the Ottoman Capital. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009.

Mansel, Philip. Constantinople: City of the World’s Desire, 1453-1924. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

Matthews, Henry. Mosques of Istanbul. Istanbul: Scala, 2010.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Introduction to the court carpets of the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal empires

Carpet weaving in the Islamic world

Carpets are woven works of art that were produced at every level of society in the Islamic world. Women have been weaving for centuries in villages and nomadic encampments all over the Middle East, Anatolia, and Central Asia, each woman passing down her techniques and designs to her daughters. These women created carpets both for sale and for their own personal use, and this tradition continues today.

Carpets were also made in the royal courts of the Islamic world. These carpets were not just functional floor coverings, they were ornate works of art that indicated the status and wealth of their owners. Court carpets were used on the floors in reception halls, audience chambers, and at court-supported religious institutions. They were also presented as impressive gifts to other rulers. Manuscript paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries suggest smaller rugs were often layered on top of larger carpets and also show that many carpets were used in outdoor pleasure pavilions and palatial parks.

Rulers had access to expensive materials, such as silk and metal-wrapped threads, and employed the most highly skilled designers and weavers in their empires to create enormous and luxurious carpets. Because of their quality, design, and skilled execution, court carpets are among the finest examples of art from the Islamic world. Court carpets are often very different from the carpets made in commercial workshops or villages. Rather than solely utilizing centuries-old traditional motifs, court carpets often share designs found on a range of media, such as bookbinding and manuscript painting.

Although carpets were made in many royal courts, the Ottoman (1281–1924), the Safavid (1501–1732), and the Mughal (1526–1858) Empires provide some of the richest examples of royally produced carpets.

Ottoman court carpets

The Ottoman Empire originated in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), and was one of the largest and longest lived in the Islamic world. It controlled territories that reached from North Africa to Eastern Europe from 1299 until 1923. Anatolia has a long tradition of carpet weaving, but from the 16th century onward Ottoman court carpets utilized a set of specific designs created by the artists of the Ottoman court workshops, designs that were also used on the court ceramics, paintings, bookbindings, and textiles.

Among the most popular of these was the “saz style,” which is characterized by long sinuous leaves, and stylized flowers (see below). Court artists also developed the “floral style,” where we see more naturalistic depictions of flowers such as tulips, roses, carnations, and hyacinths, among others. The floral and saz styles were sometimes used alone and sometimes used together, along with other motifs like the cintamani pattern (usually a combination of pearl-like circles accompanied by wavy lines sometimes called “tiger stripes”), on a huge variety of objects designed by the court, including ceramics, silks, carpets, and manuscripts.

Both the saz and floral styles appear on this rare Ottoman court prayer rug. The jagged-edged saz leaves gracefully undulate in the border amongst carnations, tulips, and other flowers. The arch at the center of the carpet identifies this as a prayer rug, and symbolizes both a mihrab (from mosque architecture) and a gateway to paradise. Such rugs were, and are, used by Muslims during the five daily prayers prescribed in Islam. Though one can go to mosque during the prayer times, prayer can take place anywhere so long as there is a clean surface (provided by the rug) and water for ritual cleansing. A luxurious prayer rug like this would have belonged to a very wealthy court patron.

The design of this remarkable carpet, the prototype for later designs, may be based on the slender-columned architecture of Muslim Spain. When Muslims and Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, many exiles settled in the Ottoman Empire, bringing with them their own visual culture, which, in turn, influenced Ottoman art. This dual-columned design spawned an entire genre of architecturally-inspired prayer rugs across Anatolia.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Ottoman court carpets is their unusual structure. Unlike all other Turkish carpets, Ottoman court carpets use S-spun wool, which is typical only of carpets woven in Egypt. Scholars attribute this unusual feature to the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517, after which the Ottoman court commissioned carpets from Egyptian workshops and had Egyptian weavers and Egyptian wool sent to Turkey for their own use.

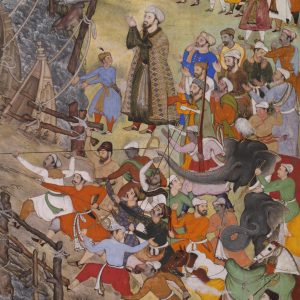

Contemporaneous manuscript illustrations shed light on how carpets were used at the court. Though we must remember that paintings are not photographs, and that artists may have invented much in their scenes, paintings like this can nevertheless tell us about the status of carpets in the court. In this painting, ordered by Sultan Murad III, a Safavid dignitary is presented to the Ottoman sultan against the backdrop of a magnificent red and blue Ushak medallion carpet. The painting shows how carpets were used as decorative and symbolic backdrops to Ottoman court rituals. Not only does the carpet provide a sumptuous setting for the ceremony, it also sends a message to the Safavids (political rivals of the Ottomans) about the wealth of the Ottoman court. We can imagine how such a carpet was used to demonstrate to visitors the power, culture, and artistic accomplishments of the Ottomans.

Safavid court carpets

The Safavids ruled Greater Iran from the early 16th to the 18th century and were avid patrons of the arts. Safavid court carpets are noted for their detailed precision, sumptuous materials, and ornate designs.

Carpets intended for religious settings, like the Ardabil carpet, display non-figural decoration such as scrolling vines, flower motifs, calligraphy, and shamsas (sunbursts). Carpets made for secular settings, like the court’s palaces and pleasure pavilions, display a wider range of motifs, encompassing the designs found on carpets like the Ardabil, but also sometimes including animals, hunting scenes, human figures, and even angels.

The carpet left is a remarkable example of a secular Safavid court carpet. It was woven entirely of silk, and its bright field is filled with animals—some real, like lions and rams, and others entirely fantastical. The animals, some of which are engaged in intense combat, are set amoungst a lush backdrop of stylized flowers and trees. The popularity of animal and hunting scenes was well established in Iran; hunting was considered a princely pastime in Iran even before the advent of Islam, and continued as a widely used subject in Safavid art.

Large scale carpets were produced by court workshops, often with similar subjects and motifs. The fragment left displays the type of central medallion seen in the Ardabil carpet, but its field and borders are filled with birds, roaming animals, and naturalistic landscape elements. Carpets like this fragment are appropriately called “paradise carpets,” reflecting their lush designs and fantastical subjects.

As with Ottoman paintings, Safavid manuscript illustrations provide insight into the use of carpets at court. In this illustration from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, a ruler is depicted seated atop a small but luxurious carpet in an outdoor pleasure pavilion. Court carpets would be used for outdoor gatherings like this, as well as within the palaces of the Safavid shahs.

Mughal court carpets

The Mughals controlled much of the Indian subcontinent from 1526 to 1858, ruling a largely Hindu population with cultural traditions foreign to their own.

It is likely India had no indigenous carpet weaving tradition prior to the arrival of Muslim conquerors. The Mughals, who traced their lineage to the Mongol dynasties in Iran and Central Asia, soon established weaving workshops at their courts.

The early Mughals employed Persian artisans, and for this reason early Mughal carpets utilize largely Persian designs. Eventually, a uniquely Mughal visual repertoire emerged in the court carpets, as well as in miniature painting and other arts.

This pictorial carpet depicts a variety of bird species in a botanically lush and naturalistic setting. The scene has direct parallels in manuscript illustration, such as the margin illumination from the album page shown above. Detailed depictions of plants and animals appear widely in Mughal art, reflecting the Mughal emperors’ interest in the natural world.

Other Mughal carpets favor an all-over flower and lattice pattern as well as other floral designs. Botanically naturalistic floral designs can be found on a wide range of media from the Mughal court, peaking in popularity during the reign of the Shah Jahan who is best known as the patron of the Taj Mahal mausoleum which incorporates similar floral designs into its architectural decoration.

Additional resources:

Conserving the Emperor’s Carpet (video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Carol Bier, ed. Woven from the Soul, Spun from the Heart: Textile Arts of Safavid and Qajar Iran, 16th–19th Centuries (Exhibition catalogue. Washington, D.C.: Textile Museum, 1987).

Jon Thompson, Oriental Carpets from the Tents, Cottages and Workshops of Asia (New York: Dutton, 1993).

Daniel Walker, Flowers Underfoot: Indian Carpets of the Mughal Era (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997)

Introduction to the court carpets of the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal empires

Carpet weaving in the Islamic world

Carpets are woven works of art that were produced at every level of society in the Islamic world. Women have been weaving for centuries in villages and nomadic encampments all over the Middle East, Anatolia, and Central Asia, each woman passing down her techniques and designs to her daughters. These women created carpets both for sale and for their own personal use, and this tradition continues today.

Carpets were also made in the royal courts of the Islamic world. These carpets were not just functional floor coverings, they were ornate works of art that indicated the status and wealth of their owners. Court carpets were used on the floors in reception halls, audience chambers, and at court-supported religious institutions. They were also presented as impressive gifts to other rulers. Manuscript paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries suggest smaller rugs were often layered on top of larger carpets and also show that many carpets were used in outdoor pleasure pavilions and palatial parks.

Rulers had access to expensive materials, such as silk and metal-wrapped threads, and employed the most highly skilled designers and weavers in their empires to create enormous and luxurious carpets. Because of their quality, design, and skilled execution, court carpets are among the finest examples of art from the Islamic world. Court carpets are often very different from the carpets made in commercial workshops or villages. Rather than solely utilizing centuries-old traditional motifs, court carpets often share designs found on a range of media, such as bookbinding and manuscript painting.

Although carpets were made in many royal courts, the Ottoman (1281–1924), the Safavid (1501–1732), and the Mughal (1526–1858) Empires provide some of the richest examples of royally produced carpets.

Ottoman court carpets

The Ottoman Empire originated in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), and was one of the largest and longest lived in the Islamic world. It controlled territories that reached from North Africa to Eastern Europe from 1299 until 1923. Anatolia has a long tradition of carpet weaving, but from the 16th century onward Ottoman court carpets utilized a set of specific designs created by the artists of the Ottoman court workshops, designs that were also used on the court ceramics, paintings, bookbindings, and textiles.

Among the most popular of these was the “saz style,” which is characterized by long sinuous leaves, and stylized flowers (see below). Court artists also developed the “floral style,” where we see more naturalistic depictions of flowers such as tulips, roses, carnations, and hyacinths, among others. The floral and saz styles were sometimes used alone and sometimes used together, along with other motifs like the cintamani pattern (usually a combination of pearl-like circles accompanied by wavy lines sometimes called “tiger stripes”), on a huge variety of objects designed by the court, including ceramics, silks, carpets, and manuscripts.

Both the saz and floral styles appear on this rare Ottoman court prayer rug. The jagged-edged saz leaves gracefully undulate in the border amongst carnations, tulips, and other flowers. The arch at the center of the carpet identifies this as a prayer rug, and symbolizes both a mihrab (from mosque architecture) and a gateway to paradise. Such rugs were, and are, used by Muslims during the five daily prayers prescribed in Islam. Though one can go to mosque during the prayer times, prayer can take place anywhere so long as there is a clean surface (provided by the rug) and water for ritual cleansing. A luxurious prayer rug like this would have belonged to a very wealthy court patron.

The design of this remarkable carpet, the prototype for later designs, may be based on the slender-columned architecture of Muslim Spain. When Muslims and Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, many exiles settled in the Ottoman Empire, bringing with them their own visual culture, which, in turn, influenced Ottoman art. This dual-columned design spawned an entire genre of architecturally-inspired prayer rugs across Anatolia.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Ottoman court carpets is their unusual structure. Unlike all other Turkish carpets, Ottoman court carpets use S-spun wool, which is typical only of carpets woven in Egypt. Scholars attribute this unusual feature to the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517, after which the Ottoman court commissioned carpets from Egyptian workshops and had Egyptian weavers and Egyptian wool sent to Turkey for their own use.

Contemporaneous manuscript illustrations shed light on how carpets were used at the court. Though we must remember that paintings are not photographs, and that artists may have invented much in their scenes, paintings like this can nevertheless tell us about the status of carpets in the court. In this painting, ordered by Sultan Murad III, a Safavid dignitary is presented to the Ottoman sultan against the backdrop of a magnificent red and blue Ushak medallion carpet. The painting shows how carpets were used as decorative and symbolic backdrops to Ottoman court rituals. Not only does the carpet provide a sumptuous setting for the ceremony, it also sends a message to the Safavids (political rivals of the Ottomans) about the wealth of the Ottoman court. We can imagine how such a carpet was used to demonstrate to visitors the power, culture, and artistic accomplishments of the Ottomans.

Safavid court carpets

The Safavids ruled Greater Iran from the early 16th to the 18th century and were avid patrons of the arts. Safavid court carpets are noted for their detailed precision, sumptuous materials, and ornate designs.

Carpets intended for religious settings, like the Ardabil carpet, display non-figural decoration such as scrolling vines, flower motifs, calligraphy, and shamsas (sunbursts). Carpets made for secular settings, like the court’s palaces and pleasure pavilions, display a wider range of motifs, encompassing the designs found on carpets like the Ardabil, but also sometimes including animals, hunting scenes, human figures, and even angels.

The carpet left is a remarkable example of a secular Safavid court carpet. It was woven entirely of silk, and its bright field is filled with animals—some real, like lions and rams, and others entirely fantastical. The animals, some of which are engaged in intense combat, are set amoungst a lush backdrop of stylized flowers and trees. The popularity of animal and hunting scenes was well established in Iran; hunting was considered a princely pastime in Iran even before the advent of Islam, and continued as a widely used subject in Safavid art.

Large scale carpets were produced by court workshops, often with similar subjects and motifs. The fragment left displays the type of central medallion seen in the Ardabil carpet, but its field and borders are filled with birds, roaming animals, and naturalistic landscape elements. Carpets like this fragment are appropriately called “paradise carpets,” reflecting their lush designs and fantastical subjects.

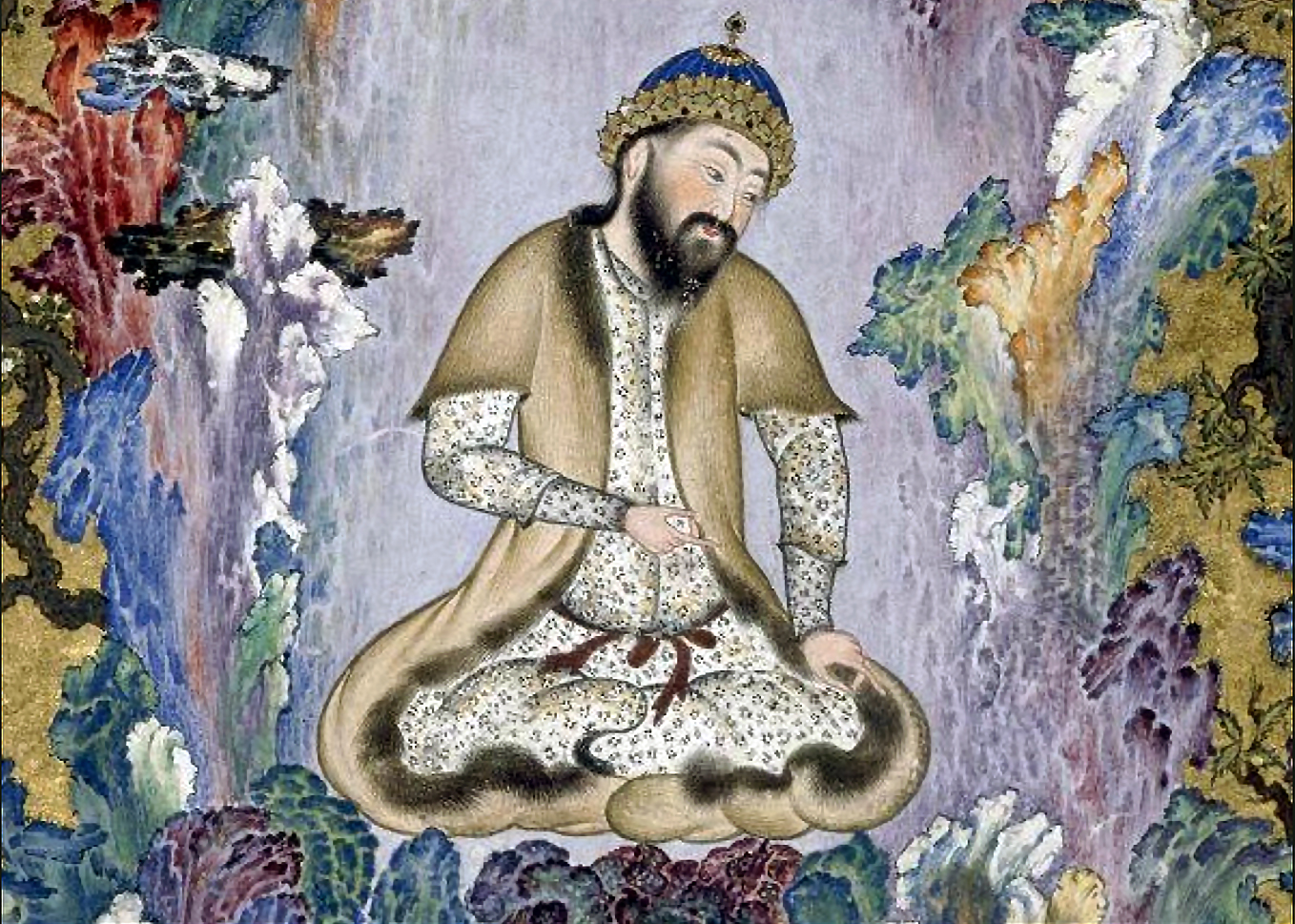

As with Ottoman paintings, Safavid manuscript illustrations provide insight into the use of carpets at court. In this illustration from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, a ruler is depicted seated atop a small but luxurious carpet in an outdoor pleasure pavilion. Court carpets would be used for outdoor gatherings like this, as well as within the palaces of the Safavid shahs.

Mughal court carpets

The Mughals controlled much of the Indian subcontinent from 1526 to 1858, ruling a largely Hindu population with cultural traditions foreign to their own.

It is likely India had no indigenous carpet weaving tradition prior to the arrival of Muslim conquerors. The Mughals, who traced their lineage to the Mongol dynasties in Iran and Central Asia, soon established weaving workshops at their courts.

The early Mughals employed Persian artisans, and for this reason early Mughal carpets utilize largely Persian designs. Eventually, a uniquely Mughal visual repertoire emerged in the court carpets, as well as in miniature painting and other arts.

This pictorial carpet depicts a variety of bird species in a botanically lush and naturalistic setting. The scene has direct parallels in manuscript illustration, such as the margin illumination from the album page shown above. Detailed depictions of plants and animals appear widely in Mughal art, reflecting the Mughal emperors’ interest in the natural world.

Other Mughal carpets favor an all-over flower and lattice pattern as well as other floral designs. Botanically naturalistic floral designs can be found on a wide range of media from the Mughal court, peaking in popularity during the reign of the Shah Jahan who is best known as the patron of the Taj Mahal mausoleum which incorporates similar floral designs into its architectural decoration.

Additional resources:

Conserving the Emperor’s Carpet (video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Carol Bier, ed. Woven from the Soul, Spun from the Heart: Textile Arts of Safavid and Qajar Iran, 16th–19th Centuries (Exhibition catalogue. Washington, D.C.: Textile Museum, 1987).

Jon Thompson, Oriental Carpets from the Tents, Cottages and Workshops of Asia (New York: Dutton, 1993).

Daniel Walker, Flowers Underfoot: Indian Carpets of the Mughal Era (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997)

The Ardabil Carpet

by DR. ELIZABETH MACAULAY-LEWIS

Old, beautiful and important

The Ardabil Carpet is exceptional; it is one of the world’s oldest Islamic carpets, as well as one of the largest, most beautiful and historically important. It is not only stunning in its own right, but it is bound up with the history of one of the great political dynasties of Iran.

About carpets

Carpets are among the most fundamental of Islamic arts. Portable, typically made of silk and wools, carpets were traded and sold across the Islamic lands and beyond its boundaries to Europe and China. Those from Iran were highly prized. Carpets decorated the floors of mosques, shrines and homes, but they could also be hung on walls of houses to preserve warmth in the winter.

Ardabil and a 14th century saint

The carpet takes its name from the town of Ardabil in north-west Iran. Ardabil was the home to the shrine of the Sufi saint, Safi al-Din Ardabili, who died in 1334 (Sufism is Islamic mysticism). He was a Sufi leader who trained his followers in Islamic mystic practices. After his death, his following grew and his descendants became increasingly powerful. In 1501 one of his descendants, Shah Isma’il, seized power, united Iran, and established Shi’a Islam as the official religion. The dynasty he founded is known as the Safavids. Their rule, which lasted until 1722, was one of the most important periods for Islamic art, especially for textiles and for manuscripts.

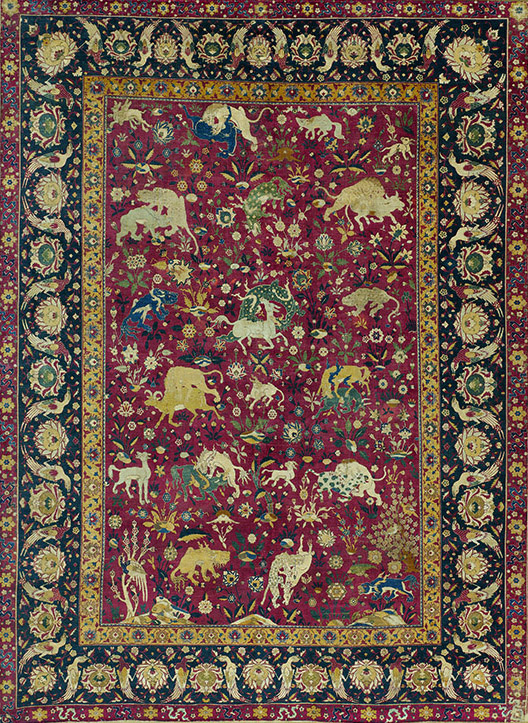

Made for a shrine

This carpet was one of a matching pair that was made for the shrine of Safi al-Din Ardabili when it was enlarged in the late 1530s. Today the Ardabil carpet dominates the main Islamic Art Gallery in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, while its twin is in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The carpets were located side by side in the shrine.

The pile of the carpet is made from wool, rather than silk because it holds dye better. The knot-count of a carpet still directly impacts the value of carpets today; the more knots per square centimeter, the more detailed and elaborate the patterns can be. The dyes used to color the carpet are natural and include pomegranate rind and indigo. Up to ten weavers could have worked on the carpet at any given time. The Ardabil carpet has 340 knots per square inch (5300 knots per ten centimeters square). Today, a commercial rug averages 80-160 knots per square inch, meaning that the Ardabil carpet was highly detailed. Its high knot count allowed for the inclusion of an intricate design and pattern. It is not known whether the carpet was produced in a royal workshop, but there is evidence for court workshop in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Design and pattern

The rich geometric patterns, vegetative scrolls, floral flourishes, so typical of Islamic art, reach a fever pitch in this remarkable carpet, encouraging the viewer to walk around and around, trying to absorb every detail of design.

That the design of the carpet was not arbitrary or piecemeal, but was well-organized and thoughtful can be seen throughout. Considering the immense size of the carpet—10.51m x 5.34m (34′ 6″ x 17′ 6″)—this is impressive. A central golden medallion dominates the carpet; it is surrounded by a ring of multi-colored, detailed ovals. Lamps appear to hang at either end.

The carpet’s border is made up of a frame with a series of cartouches (rectangular-shaped spaces for calligraphy), filled with decoration. The central medallion design is also echoed by the four corner-pieces.

Art historians have debated the meaning of the two lamps that appear to hang from the medallion. They are of different sizes and some scholars have proposed that this was done to create a perspective effect, meaning that both lamps appear to be the same size when one sat next to the smaller lamp. Yet, there is no evidence for the use of this type of perspective in Iran in the 1530s, nor does this explain why the lamps were included. Perhaps they were included to mimic lamps found in mosques and shrines, helping the viewer to look deeply into the carpet below them and then above them, to the ceiling where similar lamps would have hung, creating visual unity within the shrine.

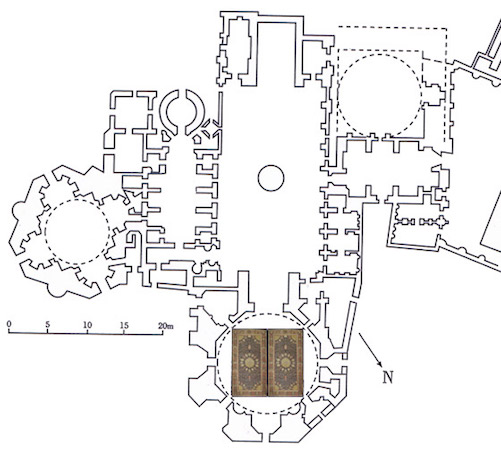

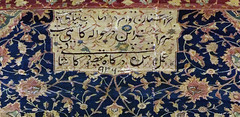

An inscription

The Ardabil Carpet includes a four-line inscription placed at one end. This short poem is vital for understanding who commissioned the carpet and the date of the carpet.

The first three lines of poetry reads:

Except for thy threshold, there is no refuge for me in all the world.

Except for this door there is no resting-place for my head.

The work of the slave of the portal, Maqsud Kashani.

Maqsud was probably the court official charged with producing the carpets. By referring to himself as a slave, he may be presenting himself as a humble servant. The Persian word for a door can be used to denote a shrine or royal court, so this inscription may imply that the royal court patronized the shrine. The carpets would have probably taken four years to make.

The fourth line of the inscription is also important. It provides the date of the carpet, AH 946. The Muslim calendar begins in the year 620 CE when Muhammad fled from Mecca to Medina; this year is known as the year of the Hijra or flight (in Latin anno hegirae). AH 946 is equivalent to 1539/40 CE (the lunar Muslim calendar does not exactly match the Gregorian Calendar, used in the west).

The design of the Ardabil carpet and its skillful execution is a testament to the great skill of the artisans at work in north-west Iran in the 1530s.

How the carpet came to the V&A

Many great treasures from around the world have legally made their way into the collections of western museums. Many objects were legally purchased by collectors and museums in the 19th and 20th centuries; however, many works of art are still illegally exported and sold. British visitors to the shrine in 1843, noted that at least one carpet was still in situ. Approximately thirty years or so later, an earthquake damaged the shrine, and the carpets were sold off.

Ziegler & Co., a Manchester firm involved in the carpet trade purchased the damaged carpets in Iran and “restored” them in fashion typical of the late nineteenth century. Selections of one carpet were used to repair the other, resulting in a “complete” carpet and one lacking a border. Vincent Robinson and Co, a dealer based in London, put the larger carpet up for sale in 1892 and persuaded the V&A to purchase it for £2000 in March 1893.

The second carpet was secretly sold to an American collector, J.P. Getty, who donated it to the LA County Museum of Art in 1953. Unlike the carpet in the V&A, the carpet in LACMA is incomplete. Throughout the twentieth century, other pieces of the carpets have appeared on the art market for sale.

Additional resources:

On the conservation of the carpet

Carpets of the Islamic World at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Ellis, Charles Grant. Oriental Carpets in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia: (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1988).

Erdmann, Kurt. Oriental Carpets: An Account of Their History, translated by Charles Grant Ellis (Fishguard, Wales: Crosby, 1976).

Jon Thompson, Carpet Magic (London: Barbican Art Gallery, 1983).

Jon Thompson, Milestones in the History of Carpets (Milan: Moshe Tabibnia, 2006).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Court of Gayumars

by DR. NANCY DEMERDASH, DR. FILIZ ÇAKIR PHILLIP, CURATOR, AGA KHAN MUSEUM and DR. MICHAEL CHAGNON, CURATOR, AGA KHAN MUSEUM

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Sultan Muhammad (attributed), The Court of Kayumars (Safavid: Tabiz, Iran), c. 1524–1525, from the Shah Tahmasp Shahnameh, c. 1524–35, opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper, 45 x 30 cm (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto) speaker: Dr. Michael Chagnon, Curator, Aga Khan Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Sultan Muhammad (attributed), The Court of Kayumars (Safavid: Tabiz, Iran), c. 1524–1525, from the Shah Tahmasp Shahnameh, c. 1524–35, opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper, 45 x 30 cm (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto) speakers: Dr. Filiz Çakir Phillip, Curator, Aga Khan Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker

The Shahnama

This sumptuous page, The Court of Gayumars (also spelled Kayumars— see top of page, details below and large image here), comes from an illuminated manuscript of the Shahnama (Book of Kings)—an epic poem describing the history of kingship in Persia (what is now Iran). Because of its blending of painting styles from both Tabriz and Herat (see map below), its luminous pigments, fine detail, and complex imagery, this copy of the Shahnama stands out in the history of the artistic production in Central Asia.

The Shahnama was written by Abu al-Qāsim Ferdowsi around the year 1000 and is a masterful example of Persian poetry. The epic chronicles kings and heroes who pre-date the introduction of Islam to Persia as well as the human experiences of love, suffering, and death. The epic has been copied countless times—often with elaborate illustrations (see another example here).

Safavid patronage

This particular manuscript of the Shahnama was begun during the first years of the 16th century for the first Safavid dynastic ruler, Shah Ismail I, but was completed under the direction of his son, Shah Tahmasp I in the northern Persian city of Tabriz (see map below). The Safavid dynastic rulers claimed to descend from Sufi shaikhs—mystical leaders from Ardabīl, in northwestern Iran. The name “Safavid” stems from one particular ancestral Sufi, named Shaykh Safi al-Din (literally translated as “purity of the religion”). Over a two-hundred-year span starting in 1501, the Safavids controlled large parts of what is today Iran and Azerbaijan (see map below). The Safavids actively commissioned the building of public architectural complexes such as mosques (image below), and they were patrons of the arts of the book. In fact, manuscript illumination was central to Safavid royal patronage of the arts.

Depicting figures

It is often assumed that images that include human and animal figures, as seen in the detail below, are forbidden in Islam. Recent scholarship, however, highlights that throughout the history of Islam, there have been periods in which iconoclastic tendencies waxed and waned.1 That is to say, at specific moments and places, the representation of human or animal figures was tolerated to varying degrees.

There is a long figural tradition in Persia—even after the introduction of Islam—that is perhaps most evident in book illustration. It is also important to note that, unlike the neighboring Ottoman Empire to the west who were Sunni and in some ways more orthodox, the Safavids subscribed to the Shi’i sect of Islam.

Two centers of culture

Although it is widely recognized that the conventions of what is sometimes termed “classical”2 Persianate painting had become established by the fourteenth century, it is in the reign of Shah Tahmasp I that we see the most dramatic advancements in illumination and the arts of the book more generally.3 His patronage of this specific art form is in part due to his own painting studies in Herat (in the western region of present-day Afghanistan) and Tabriz (in the northwestern region of present-day Iran), under Bihzad and Sultan Muhammad, respectively.4 Both cities were major centers for the production of manuscript illuminations. While the entire manuscript of the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp I consists of approximately 759 illustrated folios and 258 miniatures all produced over the span of several years,5 this particular miniature is attributed to the workshop of Sultan Muhammad, according to Dust Muhammad, an artist and historian from this period.6 In 1568, this lavish Shahnameh was given as a gift by Shah Tahmasp I to the Ottoman Sultan, Selim II.7

King of the world

There are several interpretive issues to keep in mind when analyzing Persianate paintings. As with many of the workshops of early modern West Asia, producing a page such as the Court of Gayumars often entailed the contributions of many artists. It is also important to remember that a miniature painting from an illuminated manuscript should not be thought of in isolation. The individual pages that we today find in museums, libraries, and private collections must be understood as but one sheet of a larger book—with its own history, conditions of production, and dispersement. To make matters even more complex, the relationship of text to image is rarely straightforward in Persianate manuscripts. Text and image, within these illuminations, do not always mirror each other.8 Nevertheless, the framed calligraphic nasta’liq (hanging)—the Persian text at the top and bottom of the frame (image above) can be roughly translated as follows:

When the sun reached the lamb constellation,9 when the world became glorious,

When the sun shined from the lamb constellation to rejuvenate the living beings entirely,

It was then when Gayumars became the King of the World.

He first built his residence in the mountains.

His prosperity and his palace rose from the mountains, and he and his people wore leopard pelts.

Cultivation began from him, and the garments and food were ample and fresh.10

Dense with detail

In this folio (page), we can see some parallels between the content of the calligraphic text and the painting itself. Seated in a cross-legged position, as if levitating within this richly vegetal and mountainous landscape, King Gayumars rises above his courtiers, who are gathered around at the base of the painting. According to legend, King Gayumars was the first king of Persia, and he ruled at a time when people clothed themselves exclusively in leopard pelts, as both the text and the represented subjects’ speckled garments indicate.

Perched on cliffs beside the King are his son, Siyamak (left, standing), and grandson Hushang (right, seated).11 Onlookers can be seen to surreptitiously peer out from the scraggly, blossoming branches onto King Gayumars from the upper left and right. The miniature’s spatial composition is organized on a vertical axis with the mountain behind the king in the distance, and the garden below in the foreground. Nevertheless, there are multiple points of perspective, and perhaps even multiple moments in time—rendering a scene dense with details meant to absorb and enchant the viewer.

One might see stylistic similarities between the swirling blue-gray clouds floating overhead with pictorial representations in Chinese art (image above); this is no coincidence. Persianate artists under the Safavids regularly incorporated visual motifs and techniques derived from Chinese sources.12 While the intense pigments of the rocky terrain seem to fade into the lush and verdant animal-laden garden below, a gold sky canopies the scene from above. This piece—in all its density color, detail, and sheer exuberance—is a testament to the longstanding cultural reverence for Ferdowsi’s epic tale and the unparalleled craftsmanship of both Sultan Muhammad and Shah Tahmasp’s workshops.

Notes

1. See Christiane Gruber, “Between Logos (Kalima) and Light (Nūr): Representations of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Painting,” Muqarnas 16 (2009), pp. 229-260; Finbarr B. Flood, “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum,” The Art Bulletin 84, 4 (December 2002), pp. 641-659; Christiane Gruber, “The Koran Does Not Forbid Images of the Prophet,” Newsweek (January 9, 2015).

2. For a helpful analysis of the historiographic ascription of the term ‘classical’ to Persian painting and the cultural hierarchy that was established largely by scholar-collectors in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, see Christiane Gruber, “Questioning the ‘Classical’ in Persian Painting: Models and Problems of Definition,” in the Journal of Art Historiography 6 (June 2012), pp. 1-25.

3. David J. Roxburgh, “Micrographia: Toward a Visual Logic of Persianate Painting,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 43 (Spring 2003), pp. 12-30.

4. Sheila Canby affirms Stuart Cary Welch’s estimate that it took Sultan Muhammad and his workshop three years to complete the Court of Gayumars illustration. Sheila Canby, The Golden Age of Persian Art, 1501-1722 (New York: Abrams, 2000), p. 51.

5. David J. Roxburgh, “On the Brink of Tragedy: The Court of Gayumars from Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama (‘Book of Kings’), Sultan Muhammad,” in Christopher Dell, ed., What Makes a Masterpiece: Artists, Writers and Curators on the World’s Greatest Works of Art (London; New York: Thames & Hudson, 2010), pp. 182-185; 182. The text was subsequently possessed by Baron Edmund de Rothschild and then sold to Arthur A. Houghton Jr, who in turn sold pages of the book individually.

6. Roxburgh, “Micrographia: Toward a Visual Logic of Persianate Painting,” p. 19. “In the Persianate painting, however, image follows after word in a linear sequence; the text introduces and follows after the image, but it is not actually read when the image is being viewed…In the Persian book the act of seeing is initiated by a process of remembering the narrative just told. Moreover, that text does not prepare the viewer for what will be seen in the painting.”

7. This expression denotes the beginning of spring.

8. I am grateful to Dr. Alireza Fatemi for generously providing this translation.

9. Roxburgh, “On the Brink of Tragedy,” p. 182.

Additional resources:

The Court of Gayumars at the Aga Khan Museum

Large image here (click for full-size)

Biography of the poet Abu al-Qāsim Ferdowsi, Encyclopaedia Iranica

The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

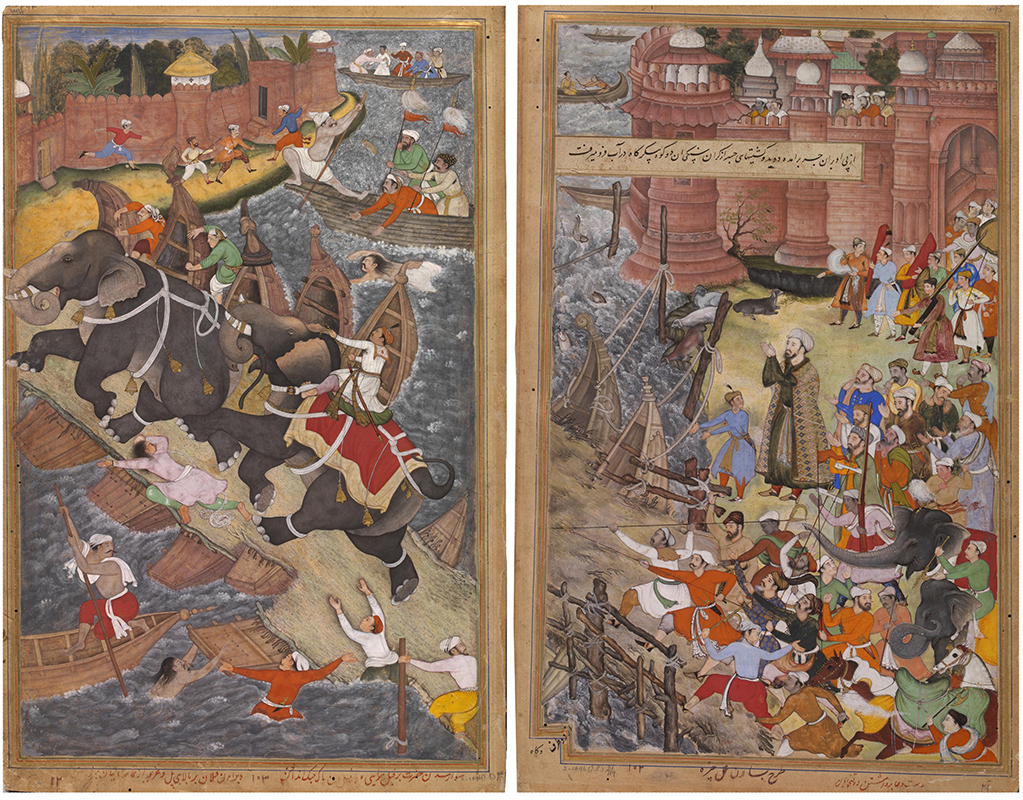

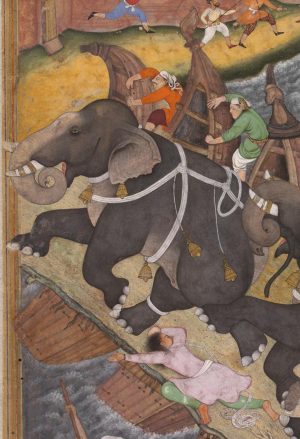

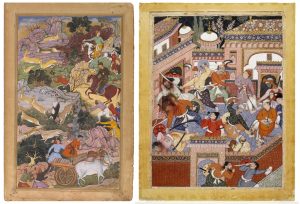

Illustration from the Akbarnama

In these small, brilliantly-colored paintings from the Akbarnama (Book of Akbar), a rampaging elephant crashes over a bridge of boats on the River Jumna, in front of the Agra Fort. He is so out of control that his tusks, trunk, and front leg burst through the edge of the frame (see image below). Several nearby men scramble to get out of the way, clinging to the edges of their boats or leaping into the water for safety. The accompanying right page shows a swirling mass of onlookers, each expressing distress and astonishment at the event unfolding before their eyes.

The scene is a royal elephant hunt where the Mughal emperor, Akbar, has mounted Hawa’i—an elephant known for its wild and uncontrollable disposition—to fight the equally fierce elephant Ran Bagha, who leads them on a wild chase across the river. The most prominent onlooker is the Prime Minister Ataga Khan, who holds his hands in prayer for a peaceful resolution to this chaotic scene. In the midst of the turmoil, we see Emperor Akbar, upright and unfazed, riding barefoot on the royal elephant—the very embodiment of majestic strength, courage, and faith in divine protection (below). These illustrations encapsulate, both symbolically and literally, the significant achievements of this remarkable man as told in the Akbarnama, the book he commissioned as the official chronicle of his reign.

Akbar the Great

Abū al-Fatḥ Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Akbar was the third emperor of a new dynasty, the Mughals, a Muslim empire established in India in the early sixteenth century by Babur, a descendent of Genghis Khan. (The name itself, Mughal, attests to this legacy, as it is the Persian and Arabic word for “Mongol”). Upon Babur’s death in 1530, the new empire was left to his 22-year-old son, Humayun, who quickly lost control of the majority of his domain as sultans fought to regain their land. In 1543 Humayun was forced to flee India and leave his young son Akbar in the care of his family at Kandahar.

These events could have led to the end of both the fledgling empire and their lives, yet circumstances took a turn that had a profound impact on the destiny of the Mughals, and in particular that of Akbar. The Safavid Shah Tahmasp I welcomed Humayun to his court in Persia (present-day Iran), not as a fugitive, but as an equal, granting him protection and military support. Immersed for two years in the refinement and splendor of the arts and culture there, Humayun was exposed to an opulence and sophistication unlike anything he had ever seen in his father’s military encampments. As a result of his stay in Iran, the original language of the Mughals was abandoned in favor of Persian, monumental architectural forms were adopted and refined, and an imperial workshop of painters in the Persian miniature style was founded. Reunited with his son in 1545, Humayun eventually regained control of India before dying suddenly in 1556. When Akbar inherited the Mughal territories at 13 years old, he was surrounded by rivals on all sides: there was no stable government, no art the empire could call its own, and not much hope for a future. However, within less than 50 years, Akbar created all of these things and succeeded in bringing together the diverse peoples and cultures of India to form an unprecedented, cooperative whole. Akbar was instrumental in the formation of a powerful empire that lasted over 200 years.

Across many cultures and time periods, a ruler’s control over the natural world is a defining symbol of noble power, and Mughal India was no exception. Akbar’s regal authority, military prowess, and personal courage are visibly celebrated in this painting through his complete control of an elephant—an animal with a long history in Indian culture as the embodiment of majesty, power, and dignity. Yet this illustration shows us Akbar’s great triumphs in more than just the subject matter: the innovations in the work’s artistic style are also reflective of the acute intelligence, voracious curiosity, and enthusiastic artistic sponsorship for which Akbar is remembered.

Mughal painting under Akbar the Great

Akbar was a champion of new styles in literature, architecture, music, and painting. Although he was illiterate, at the time of his death in 1605 the imperial library contained 24,000 volumes, and the number of painters in the imperial workshop had expanded greatly. Much like his political policies, which encouraged tolerance, Akbar’s court included artists from all regions of India, creating a melting pot of techniques and styles. As a result, Mughal painting under Akbar the Great is known for its unique blend of indigenous Indian, Persian, and Western traditions.

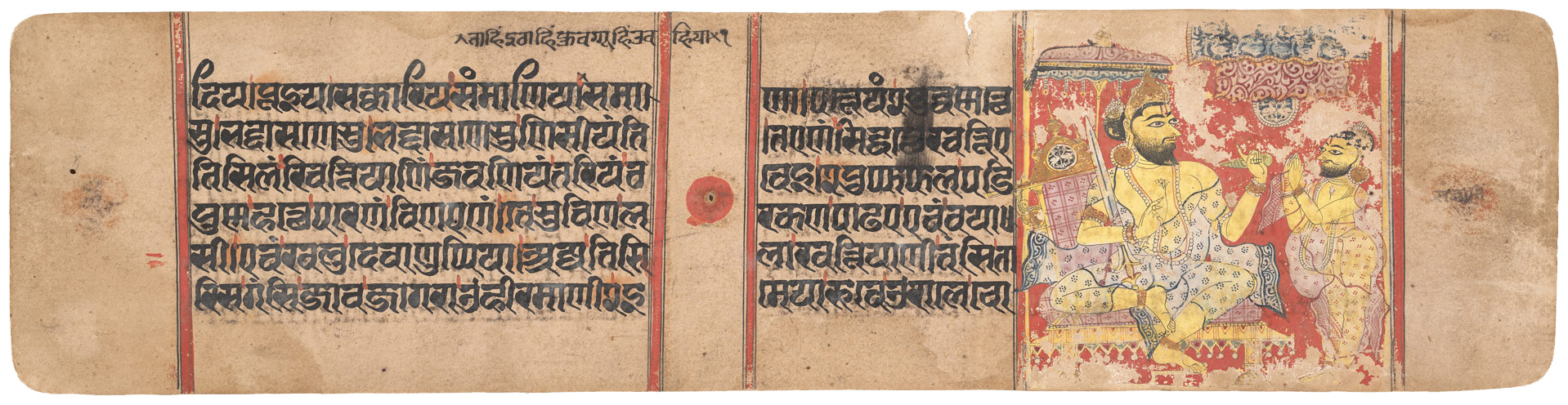

This page from a Kalpasutra manuscript from the fourteenth century beautifully illustrates the basic qualities of the Indian tradition, with its use of bold primary colors and its horizontal format. The visual emphasis is on the text, which occupies roughly two-thirds of the page. Although the illustration (which shows King Siddhartha speaking to an astrologer who will foretell his son’s birth) takes up the smallest portion of the page, the size of the figure is very large in relation to the picture plane, with the king’s form filling up the space of the frame.

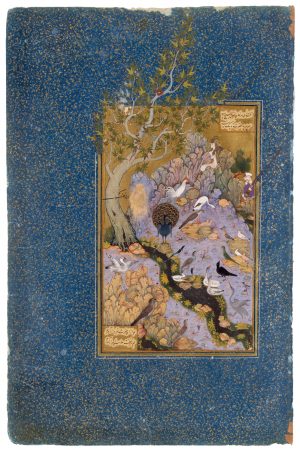

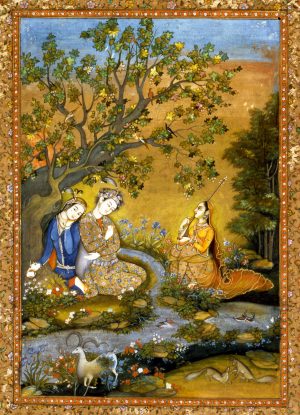

In contrast, the Persian tradition (above) preferred a vertical format, with greater emphasis on landscape and decorative elements. In “The Concourse of the Birds,” an illustration of a mystical poem made around 1600, the color palette is much more subdued, with a preference for pastel colors like pinks, soft blues, and soft greens. The figures in the painting are relatively small, completely embedded within a scene that is rendered with painstaking detail. The subject matter of this type of manuscript—typically poetry or the pleasures of courtly life—was meant to illustrate the elegance and refinement of the ruler. How could it be possible to blend two such disparate artistic traditions?

To further complicate matters, Western missionaries made contact with Akbar in the late sixteenth century, bringing with them European artworks and religious texts illustrated with engravings. Akbar and his expansive atelier of painters were intrigued by the illusion of depth achieved through linear perspective, as well as by novel visual attributes such as halos on religious figures. Some scholars have characterized these Western artistic traditions as the ultimate goal to which Akbar and his painters aspired; however, many Islamic artists instead integrated this new visual vocabulary into their own rich traditions. In “Lovers in a Landscape” (above), a miniature made by Mir Kalan Khan in the eighteenth century, the two figures on the left are distinctly Persian in style, with three-quarter views of their faces, slender, swaying bodies, and densely patterned clothing. By contrast, the woman on the right is seen in profile, with hints of Western-style depth and volume such as the gentle folds of drapery. Through the balance of seemingly contradictory styles, the artist has created a scene with two levels of reality: it is as if the female musician on the right, reciting a traditional Persian love story, is singing the fictional couple into physical existence.

The elephant hunt: a blend of styles

The artists in Akbar’s atelier were equally proficient at blending elements from Indian, Persian, and Western traditions, while developing a distinct style of their own. In the illustration of the elephant hunt from the Akbarnama, they have retained the vertical format favored in Persian painting, as well as its traditionally intricate patterning of nature, seen in the rhythmic pulsing of the waves. In the right panel, the onlookers express fear and awe through the standardized Persian gesture of lightly pressing a finger to the lips. Yet many other figures are seen with their arms thrown overhead in distress, or with their bodies positioned off-balance, demonstrating the artists’ independence in choosing whether or not to utilize standard gestures.

The vibrant hues, on the other hand—especially the deep reds and yellows—call to mind the Indian tradition and its preference for saturated primary colors. The scale of the figures in relation to the picture plane is also much larger than in the Persian style, demonstrating a preference for the Indian tradition’s emphasis on the human form. Elements from Western artistic traditions are also present, most notably the indication of depth and distance achieved by rendering the boats and buildings as increasingly small as one looks to the top of the page.

Clearly, these artists enjoyed a remarkable degree of freedom to experiment and develop new artistic amalgams under Akbar’s patronage. Akbar’s court historian, Abu’l Fazl, noted the intense personal interest taken by Akbar in his workshop, where he personally commissioned specific subjects and conducted regular viewings of new work each week. In the illustrations of the elephant hunt, we can see his preference for depictions of heroic personal feats. From the sharp diagonal placement of the elephants upon their precarious bridge of boats, to the depiction of the thrilling story at its climax, this scene is full of vigor, action and excitement.

Other examples of such themes abound in Mughal art, such as a hunting scene from the Akbarnama which shows the decisive moment the cheetah tears into its prey (above left), or the scene of a prison break from the Hamza Nama manuscript, with blood spurting from the necks of those recently beheaded (above right). Yet the elephant hunt illustration is also more than a dynamic illustration of a charismatic emperor. In it we can see the new, innovative style distinct to Akbar and his court, where the personality of the ruler and a cosmopolitan blend of styles resulted in art that was unmistakably Mughal.

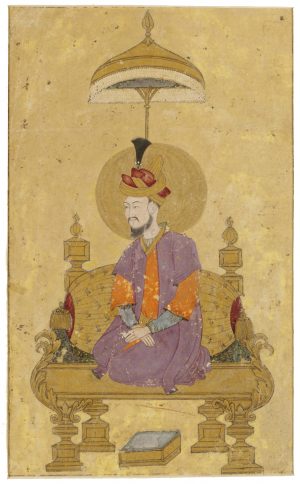

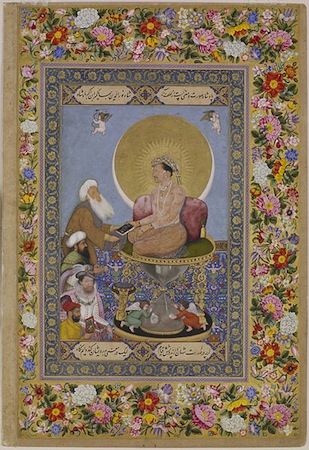

Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings

Seizer of the world

When Akbar, the third Emperor of the Mughal dynasty, had no living heir at age 28, he consulted with a Sufi (an Islamic mystic), Shaikh Salim, who assured him a son would come. Soon after, when a male child was born, he was named Salim. Upon his ascent to the throne in 1605, Prince Salim decided to give himself the honorific title of Nur ud-Din (“Light of Faith”) and the name Jahangir (“Seizer of the World”).

In this miniature painting, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings, flames of gold radiate from the Emperor’s head against a background of a larger, darker gold disc. A slim crescent moon hugs most of the disc’s border, creating a harmonious fusion between the sun and the moon (thus, day and night), and symbolizing the ruler’s emperorship and divine truth.

Jahangir is shown seated on an elevated, stone-studded platform whose circular form mimics the disc above. The Emperor is the biggest of the five human figures painted, and the disc with his halo—a visual manifestation of his title of honor—is the largest object in this painting.

Jahangir favors a holy man over kings

Jahangir faces four bearded men of varying ethnicity, who stand in a receiving-line format on a blue carpet embellished with arabesque flower designs and fanciful beast motifs. Almost on par with the Emperor’s level stands the Sufi Shaikh, who accepts the gifted book, a hint of a smile brightening his face. By engaging directly only with the Shaikh, Jahangir is making a statement about his spiritual leanings. Inscriptions in the cartouches on the top and bottom margins of the folio reiterate the fact that the Emperor favors visitation with a holy man over an audience with kings.

Below the Shaikh, and thus, second in the hierarchical order of importance, stands an Ottoman Sultan. The unidentified leader, dressed in gold-embroidered green clothing and a turban tied in a style that distinguishes him as a foreigner, looks in the direction of the throne, his hands joined in respectful supplication.

The third standing figure awaiting a reception with the Emperor has been identified as King James I of England. By his European attire—plumed hat worn at a tilt; pink cloak; fitted shirt with lace ruff; and elaborate jewelry—he appears distinctive. His uniquely frontal posture and direct gaze also make him appear indecorous and perhaps even uneasy.

Last in line is Bichitr, the artist responsible for this miniature, shown wearing an understated yellow jama (robe) tied on his left, which indicates that he is a Hindu in service at the Mughal court—a reminder that artists who created Islamic art were not always Muslim.

This miniature folio was once a part of a muraqqa’, or album, which would typically have had alternating folios containing calligraphic text and painting. In all, six such albums are attributed to the rule of Jahangir and his heir, Shah Jahan. But the folios, which vary greatly in subject matter, have now been widely dispersed over collections across three continents.