5.8: South Asia (II)

- Page ID

- 68316

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Great Relief at Mamallapuram

A cat stands on one leg in imitation of a holy man while plump mice gather around. A family of elephants, with several calves in tow, approaches a river to drink. Half human-half snake figures slither up a crevice. Holy men stand on one foot while gazing into the sun. All these and more—including over one hundred depictions of humans, deities, spirits and animals—populate a massive relief sculpture, often called The Great Relief, near the coast in Mamallapuram (also known as Mahabalipuram), in southeast India. This particular relief is the most well-known of the monuments at Mamallapuram that were carved from massive granite boulders naturally scattered throughout the region (there are over one hundred of these in situ carvings). This carving is one of the largest relief sculptures in the world, measuring 83 x 38 feet (25 x 12 meters), covering most of the faces of two adjoining boulders, with a large cleft in the center.

This enigmatic artwork was created during the Pallava Dynasty (third-ninth centuries C.E.). Despite its long history of at least 1,200 years and plenty of scholarly attention, experts remain uncertain about its precise subject matter. It has been variously interpreted as a visual narrative of the “Descent of the Ganges,” “Arjuna’s Penance,” or other stories from the vast Hindu tradition.

Who were the Pallavas?

The origins and chronology of the Pallava rulers are ambiguous, but they seemed to have come from the north and taken advantage of a power vacuum in southeast India during the third or fourth centuries C.E. They ruled from the nearby capital at Kanchipuram while utilizing Mamallapuram as a port city and for religious monuments and rituals. Pallava rule peaked in the seventh and eighth centuries C.E. During this time, the ruler Narasimhavarman I commissioned the monuments at Mamallapuram. He was a devout Hindu as well as a lover of the arts. One of the challenges of learning about Indian history and philosophy is that a given person, deity, or place is often known by many different names. In this case, Narasimhavarman I was also known as Kala Sumatra, “Ocean of the Arts.”

The Descent of the Ganges?

The “Descent of the Ganges” is a well-loved Hindu story about the origins and religious significance of the sacred Ganges river. The story tells how the gods allowed the Ganges to descend from the heavens to reward a sage named Bhagiratha, who had practiced many years of spiritual devotion. The water from the river was meant to purify the ashes of Bhagiratha’s deceased ancestors while providing life-giving water to all creatures, great and small. To prevent the force of the cascade from destroying the earth, Lord Shiva (one of the primary deities of Hinduism) manifested under its fall and allowed the water to get caught in his long, matted hair so that it trickled out in gentle tributaries.

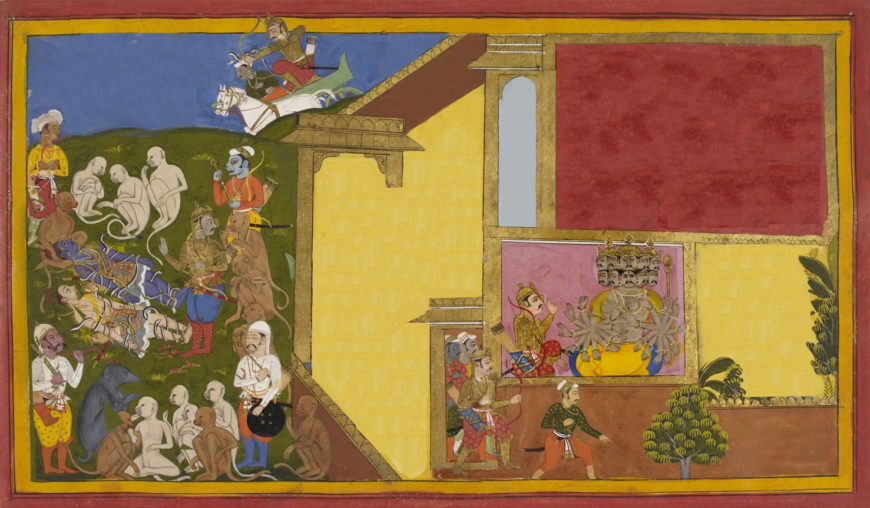

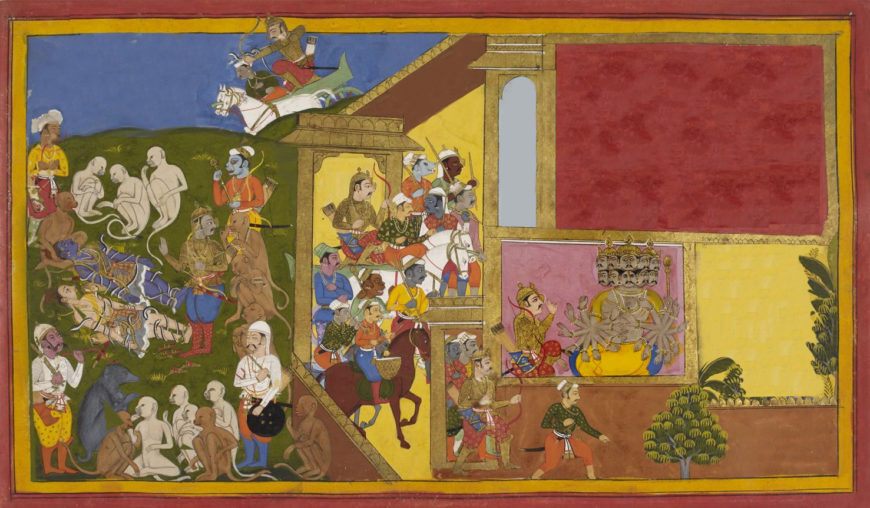

On the Mamallapuram relief, Shiva is depicted as one of the largest figures along with an ascetic (a holy man in a yoga pose—see image below). We know that this is Shiva because he is shown with the common attributes of the god: four arms, a crown of hair piled atop his head, and holding his favored symbol, the trident.

However, he is not shown in the typical manner of the “Descent of the Ganges” story—in his role of savior, allowing the sacred waters to fall on his head. Some traditional depictions of Shiva include a small mermaid-like figure in his hair, symbolizing Ganga as a personification of the Ganges River. Here at Mamallapuram, though, Ganga is not depicted in anthropomorphic (human-like) form or as a sculpted depiction of water, but may instead have been represented by actual water that would have flowed down the cleft of the rock. Contributing to the interpretation that the central cleft represents a channel for the Ganges as it falls from heaven are the sculptures of three Nagas (image above). Nagas are snake deities that embody the qualities of fertility and prosperity, and act as protectors of bodies of water. Scholars believe that a concave depression in the top of the boulder collected water which was then sent down the central cleft in imitation of the falling Ganges.

This may have been done especially frequently during the wet monsoon season, serving as a visual indication of the divine authority of the Pallava kings as they recreated this important religious story for onlookers and dignitaries. The Pallavas controlled the Kaveri, a local river and a source of their political strength in the region. It is likely that the rulers wanted to symbolically connect the Kaveri and the Ganges to remind viewers of both their earthly and divine power.

Arjuna’s Penance?

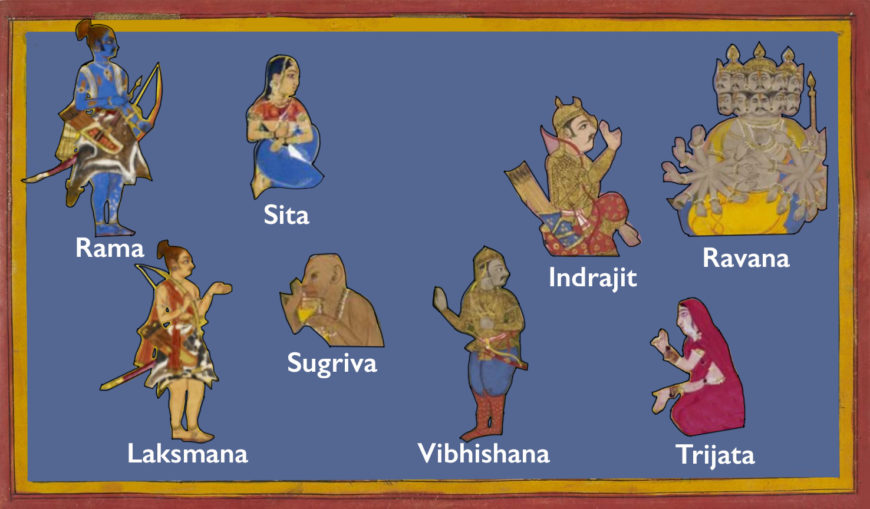

A second interpretation focuses not on the Ganges, but on the devotion of the archer Arjuna, hero of the epic Mahabharata. The conflicts between the cousins of Arjuna (the Kauravas) and his brothers (the Pandavas) are legendary and form the focal point of this grand tale.

If this interpretation is correct, part of the scene at Mamallapuram (shown here) may depict the famed warrior Arjuna beseeching the god Shiva to provide him with his powerful weapon in aid against his enemies. Arjuna may be one (or all) of the figures depicted performing yogic devotion. In the detail here, a four-armed Shiva appears to be presenting a small figure with a fearsome face on his belly to the holy man who may be Arjuna and who stands on one leg. This small figure may be a personification of pashupatastra, Shiva’s most fearsome weapon.

A special relationship to the Gods

The protagonists of both interpretations—Arjuna and Bhagiratha—are heroic individuals who, through their penance, have a special relationship to the gods. Arjuna and Bhagiratha were protectors of their families, clans, and the earth. The relief may express the idea that the Pallava rulers, through their special connection to gods, were protectors of their lands and people.

The Joyful Element: Something for Everyone?

The Great Relief is complex and it is likely that very few people grasped all of its layers of meaning. The casual viewer may have been drawn to the amusing elements of the Great Relief. Perhaps the best known detail in this vein is the cat who acts like a holy man (standing on one leg!) surrounded by unsuspecting mice who will soon become his dinner (image above). Charming elephants and their playful calves also lumber into the scene. But the elephants may also have additional significance—they may symbolize the protective capacity of the Pallava rulers over their people, since in the real world elephants almost always have just a single calf, and here we see at least seven.

Punctuating the entire relief are a multitude of fantastic beasts, hybrid figures, and airborne deities. These extraordinary representations allow anyone to enjoy the relief even with little or no understanding of its complex mythology. These delightful scenes may have provided an “entry point” for viewers in the seventh century just as they do today, while more learned viewers would recognize deeper layers of meaning.

Conflicting Stories or Multiple Meanings?

Hinduism is populated with a vast number of gods and goddesses (along with their manifestations or avatars), as well as saints, demons, demigods, and beasts. It is a belief system that is often multi-layered and seemingly contradictory; the fortunes of gods and humans alike shift frequently while time and space and good and evil are fluid and ever-changing. In light of this unstructured quality of Hinduism (as compared to many other religions), the contemporary non-Hindu viewer of these monuments shouldn’t be too concerned that there is some ambiguity in the Great Relief. In an excellent article about the relief, the scholar Padma Kaimal emphasizes its “playful ambiguity” and remarks that “the absence of … such unequivocal signs creates space for the coexistence and interaction of multiple voices and therefore meanings.” [1] She draws a parallel between the visual art and the language of the Pallava court—both incorporate puns and multilayered meanings. The art historian Michael Rabe similarly contends that the work may have been intentionally created as “a deliberate conundrum,” allowing the viewer to witness intermingled and “repeated occasions when Shiva’s favor has been bestowed.” [2] The Pallava rulers glorified Shiva as the most significant deity, so it is logical that the focus here would be on stories connected to that god.

Whatever the correct interpretations are, this sculpture appears to incorporate religious storytelling, allusions to Pallava power and protection, and joyful scenes of animals, people, and deities. Some elements of the relief would appeal to educated members of the court and the priestly class, others to visiting dignitaries, and still others to the average citizen. Today, as in the preceding fourteen centuries, the Great Relief at Mamallapuram does not fail to impress as it draws visitors from across India and the rest of the world. Even when not fully understood, the Great Relief contains something for everyone.

Notes:

[1] Padma Kaimal, “Playful Ambiguity and Political Authority in the Large Relief at Mamallapuram,” Ars Orientalis 24 (1994), pp. 1-27.

[2] Michael Rabe, The Great Penance at Māmallapuram: Deciphering a Visual Text (Institute of Asian Studies, 2001), p. xxii.

Additional resources:

Edward Wong, “Temples Where Gods Come to Life,” New York Times, September 19, 2009.

Hinduism and Hindu art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Shore Temple, Mamallapuram

Seashore as canvas

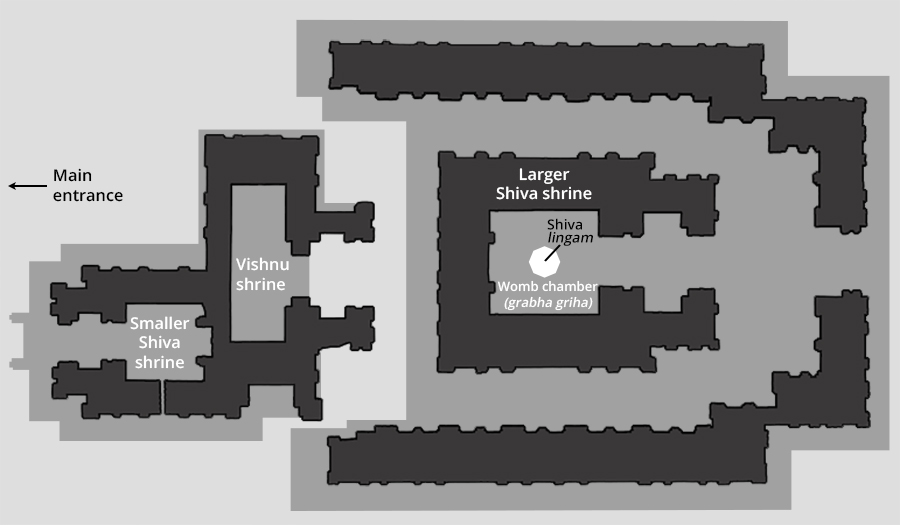

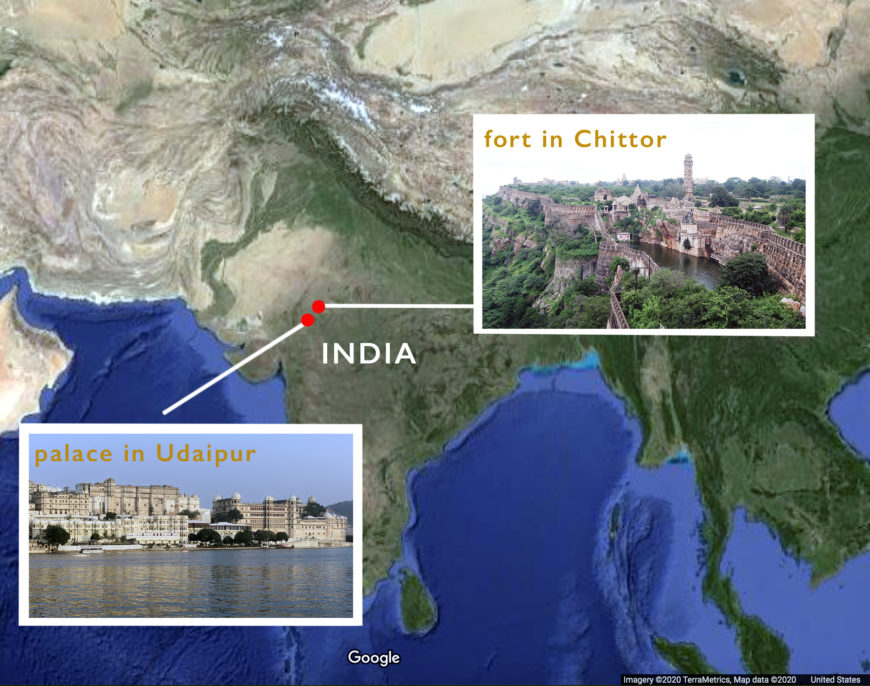

Along the shores of one of the largest bays in the world, the Bay of Bengal, stands a temple complex that draws inspiration from the sea and its naturally occurring rock formations. The majestic Shore Temple (known locally as Alaivay-k-kovil) sits beside the sea in the small town of Mamallapuram in the state of Tamil Nadu in India. This complex of three separate shrines was constructed under the patronage of the Pallava king Nrasimhavarman II Rajasimha, who ascended the throne in 700 C.E. and ruled for about twenty years.

The Pallavas and the city of Mamallapuram

Mamallapuram, also known as Mahabalipuram, was an important port town during India’s early history and developed as a key center for artistic activity under the patronage of the Pallava rulers. Narasimhavarman I, who took the epithet Mamalla (meaning “great warrior”), ruled for about 38 years beginning in 630 C.E. and sponsored a large number of rock-cut monuments at Mamallapuram, including cave shrines, monolithic temples, and large sculptures carved out of boulders. While the Pallava kings primarily worshipped the god Shiva, they also supported the creation of temples dedicated to other Hindu gods and goddesses and to other religious traditions such as Jainism. The Pallava rulers were particularly inspired by the growing personal devotional movement known as bhakti.

A temple in Dravidian style

Indian temple architecture can be broadly divided into two schools: the Nagara, or the North Indian tradition, and the Dravidian, or South Indian style of architecture. Both Nagara and Dravidian temples consist of a main shrine (vimana) which houses the inner sanctum known as grabha griha (literally “womb chamber”), topped by a pyramidal tower known as a sikhara. At the Shore Temple, the entire superstructure has an octagonal neck (griva) topped by a round stupi or finial. Dravidian temples are typically enclosed within an outer wall (prakara, shown below) with a large gateway tower known as a gopura.

The development of early Indian architecture demonstrates a progression from structures of wood and timber to cave shrines, rock cut structures, and eventually freestanding temples constructed out of mortar and stone. Cave shrines were dug into cliffs and hills and their scheme and ornamentation clearly exhibit the continuing influence of traditions used in earlier wooden structures. The rock cut temples were constructed out of large freestanding boulders that artists would work by carving the rocks from the top to the bottom on both the exterior and interior simultaneously.

A temple with three shrines

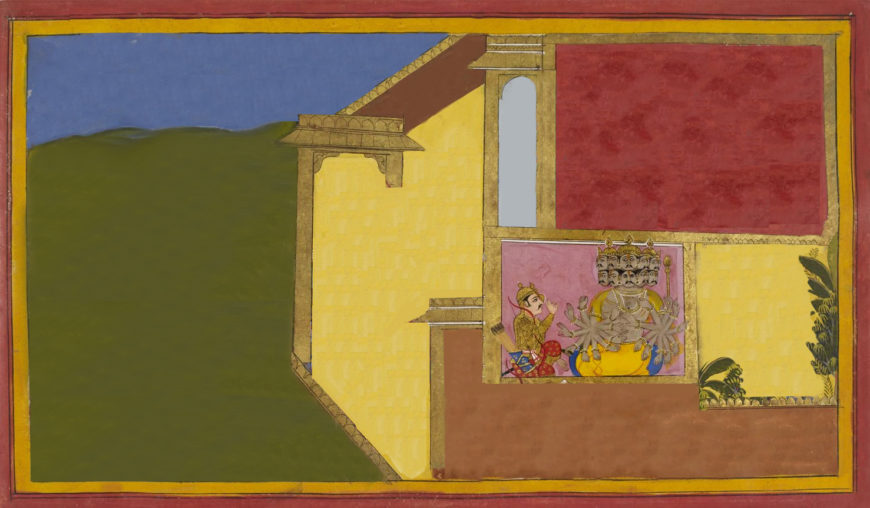

The Shore Temple is both a rock cut and a free-standing structural temple. The entire temple stands on a naturally occurring granite boulder. The complex consists of three separate shrines: two dedicated to the god Shiva, and one to Vishnu. The Vishnu shrine is the oldest and smallest of the three shrines. The other elements of the temple, including the gateways, walls, and superstructures were constructed out of quarried stone and mortar.

The entrance to the temple complex is from the western gateway, facing the smaller Shiva shrine. On each side of the gateway stand door guardians known as dvarapalas who welcome visitors to the complex and mark the site as sacred. The smaller Vishnu temple sits between the two Shiva shrines, connecting the two. It has a rectangular plan with a flat roof and houses a carved image of the god Vishnu sleeping. Images of Vishnu reclining or sleeping on the cosmic serpent Shesha-Ananta, appear throughout Indian art. While the artists who made this carving did not include a depiction of Shesha-Ananta, it is possible that originally the rock was painted to include the snake. The shrine walls have carvings depicting the life stories of Vishnu and one of his avatars, Krishna.

Like the Vishnu shrine, the two Shiva shrines include rich sculptural depictions on both their inner and outer walls. The large Shiva shrine faces east, and has a square plan with a sanctum and a small pillared porch known as a mandapa. At the center of the shrine is a lingam, the aniconic form of Shiva in the shape of a phallus. Though the temple is not a site of active worship today, visitors can sometimes be seen worshipping and offering flowers to the lingam, bringing the sacred site back to life.

On the back wall of the shrine appear carvings of Shiva (this time in anthropomorphic or human-like form) with his consort, the goddess Parvati, and their son Skanda. The inner walls of the mandapa contain images of the gods Brahma and Vishnu, and the outer north wall of the sanctum includes more sculptures of Shiva as well as a depiction of the goddess Durga. The small Shiva shrine faces west and has a square plan with a sanctum and two mandapas. As with the larger Shiva shrine, the smaller shrine’s sanctum originally housed a lingam, which is now missing. A sculpted panel depicting Shiva, Parvati, and Skanda enlivens the back wall. Both Shiva shrines have identical multi-storied pyramidal superstructures typical of the Dravidian style.

The rich sculptural program seen throughout the three shrines continues on the outer walls of the Shore Temple, facing the sea. Years of wind and water have worn away the details of these carvings, much in the same way that the sea erodes and shapes boulders over centuries. A row of seated bulls appear at the entrance wall (prakara) of the larger Shiva shrine. These bulls represent Nandi, the vahana or vehicle of the god Shiva. Nandi is believed to be the guardian of Shiva’s home in the Himalayas, Mount Kailasha, and a seated Nandi sculpture is an essential part of a Shiva temple.

A majestic sight

As an architectural form, the Shore Temple is of immense importance, situated on the culmination of two architectural phases of Pallava architecture: it demonstrates progression from rock cut structures to free standing structural temples, and displays all the elements of mature Dravidian architecture. It signifies religious harmony with sacred spaces dedicated to both Shiva and Vishnu, and was also an important symbol of Pallava political and economic strength.

According to legend, sailors and merchants at sea could spot the shikharas of the temple from a distance and use those majestic towers to mark their arrival to the prosperous port city of Mahabalipuram. In this way, not only was the temple a home for the gods Shiva and Vishnu, but also a feature of the landscape, and an icon of the dominion of the great Pallava kings.

Additional resources:

Michael W. Meister, ed. Encyclopeadia of Indian Temple Architecture: South India Lower Drāviḍadēśa 200 B.C.-A.D.1324, vol. I, part I (New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, 1983)

Susan L. Huntington, The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain (New York: Weatherhill, 1985)

R. Nagaswamy, Mahabalipuram (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008)

Durga Slays the Buffalo Demon at Mamallapuram

An epic battle

Imagine the anguish of the gods as the end of their reign neared. A seemingly invincible buffalo demon, Mahishasura, had already conquered the world and seemed poised for victory over the heavens. Could he be stopped? It seemed unlikely — Mahishasura had, after all, received a special gift from the god Brahma — an assurance that the demon could never be killed by man or god.

Just then, when all seemed lost, a great mass of blazing energy began to radiate from the gods. It moved and coalesced until finally, shakti (“force” in sanskrit—a formless energetic entity that is feminine and divine) materialized. She was a sight to behold: beautiful, strong, and riding a fierce lion, she was endowed with the weapons and the power of each of the gods.

The buffalo demon Mahishasura was quite sure that a woman could never defeat him and promptly proposed marriage. Her cool rejection led to battle and in the end, the goddess effortlessly pierced him with a trident, decapitated him, and sent his army scurrying. With the heavens and the world saved, the goddess promised to help the gods and the earth whenever she was needed.

The story of Mahishasuramardini (in Sanskrit: “crusher of Mahishasura”) is preserved in a devotional text from c. 600 C.E. titled the Devi Mahatmya (“Glory of the Goddess”) which exalts the divine feminine force shakti, also known as Mahadevi.

This episode, which recounts the deeds of the goddess Chandika (later known as Durga), a fierce warrior, is carved in an exquisite bas-relief panel inside a rock-cut cave temple known as Mahishasuramardini mandapa (hall) in the town of Mamallapuram in Tamil Nadu, India. [1]

Mamallapuram was an important port in the medieval period in the Pallava kingdom. It is well known for its temples and rock-cut monuments that were built by the Pallava rulers and date between the sixth and the eighth centuries C.E.

From the carved walls of Hindu temples, to manuscript paintings, murals, and contemporary art, Durga’s encounter with Mahishasura has been a popular subject among artists in South Asia and Southeast Asia for centuries. In temples and religious sculpture, she is often depicted as either calmly victorious standing on a decapitated buffalo head (as in the sculpture at The Metropolitan Museum of Art) or in the act of killing a buffalo-headed figure from whose cut neck a demon in the form of a man emerges. The seventh-century sculptors in Mamallapuram chose to portray the battle just prior to the goddess’s triumph over the demon. [2]

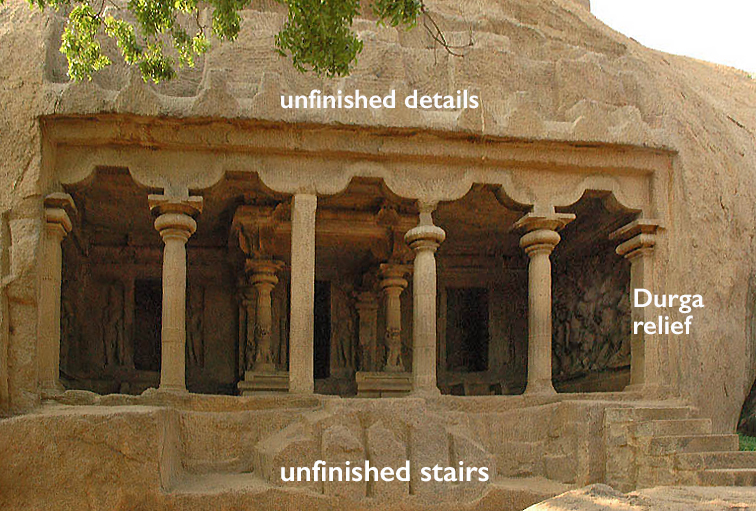

Carved from stone

The Mahishasuramardini relief is located in a rectangular granite rock-cut cave dedicated to the god Shiva. The temple is carved from an enormous boulder that also carries the constructed (as opposed to rock-cut) Olakkanesvara temple on the rock’s summit. The cave temple is open to the east with four widely spaced columns, allowing light to enter (though the windowless shrines at the rear of the temple remain dark). Like many monuments at Mamallapuram, the Mahishasuramardini mandapa was left unfinished; note, for instance, how the stairs have been outlined but not carved on the exterior of the cave. [3]

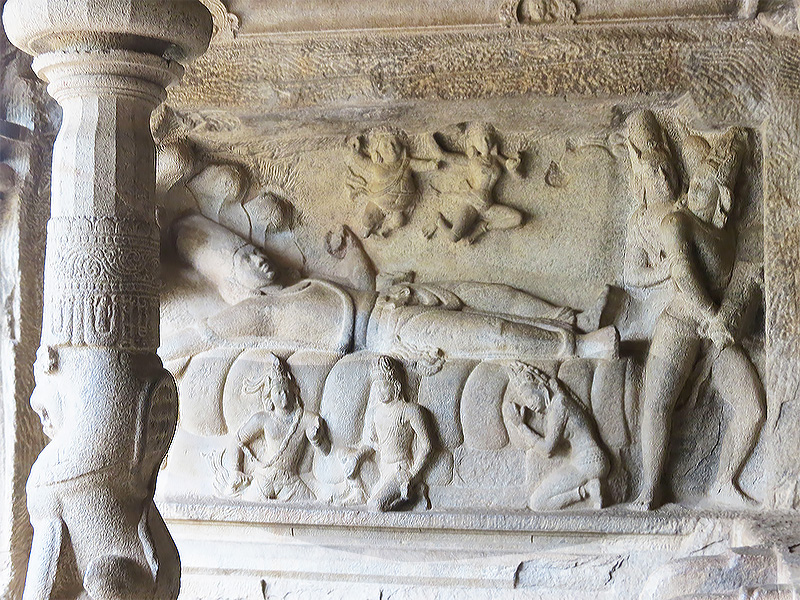

The relief panel is large at a little over eight feet tall and nearly fifteen feet long. It is carved in a niche on the north side of the cave (that is, to your right as you enter the temple) and is a contrast to the equally large but far less dynamic panel opposite (image below). That panel, on the south side of the cave, shows the god Vishnu resting on the giant serpent Shesha. Here, Shesha protects Vishnu from the ill-will of the two figures on the far right side of the panel who hurriedly leave the scene.

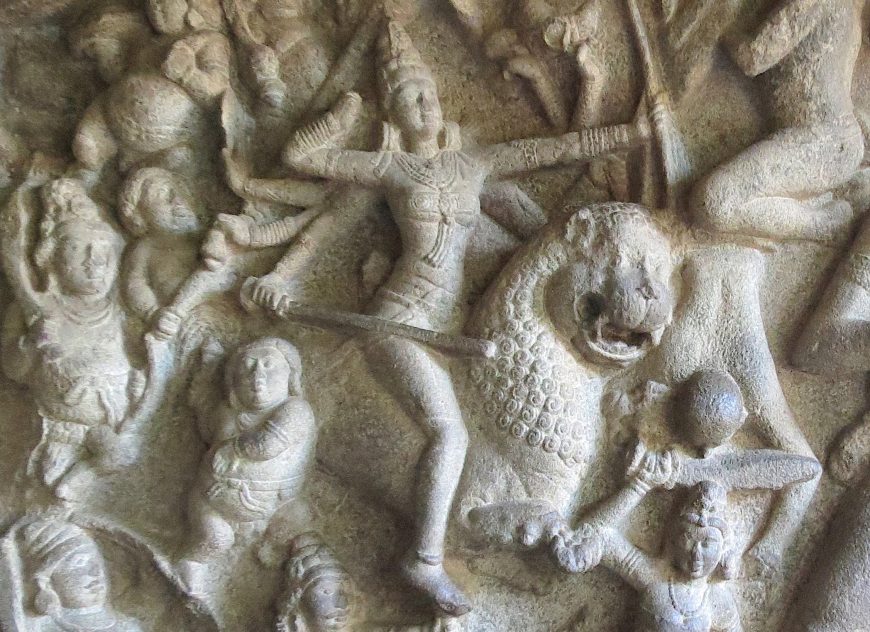

Riding to victory

In opposition, the energetic spectacle of Mahishasuramardini is clearly a scene of battle. The sculptors cleverly manipulated the depth of the relief to convey the liveliness of the clash between good and evil; the modulation of shallow and deep carving allow the goddess and her army to materialize from the background, as if by surprise, while the buffalo demon and his army — all of whom are depicted as men — hasten their retreat. Mahisha, the seated soldier at the far bottom right of the niche, and the soldier above him who is running with a shield and sword, are carved so deeply that their exit from the battle, the relief, and even the temple itself, seems imminent.

The goddess is roughly life-sized and draws her bow as she steadies an implied arrow. [4] The weapons in her six other arms have been identified, in clockwise order:

- a sword

- a bell

- a wheel (or discus)

- a noose to restrain her enemies

- a conch shell

- a shield [5]

She is shown wearing a dhoti (cloth tied at the waist) — notice the hem just above the knee that delineates the garment — and a kuca bandha (breast band). Like the kuca bandha, the dhoti may have once carried patterned details, but this is no longer visible. Durga is also adorned with a distinct crown and jewelry including large earrings, necklaces, bangles, armlets, belt, and anklets, all of which demonstrate her divinity and royalty. Even the goddess’s vahana (vehicle), a lion, is beautifully ornamented with a mane of neatly demarcated ringlets.

Durga is surrounded by an entourage of several gana (small, male attendants) and a singularly remarkable female warrior at the bottom center who is raising her sword (see detail below). In addition to gana who support the goddess in battle, see for instance the moustached gana who stands beneath her foot and takes aim at the villains, again, with an implied arrow, and the others that appear at the ready with sword and shield, there are gana who underscore the goddess’s identity as both divine and royal. Two gana carry attributes signifying royalty (i.e., a parasol and a fly-whisk) above the goddess and another (at the top-left) flies into the scene holding a plate with offerings for Durga.

The scene is cleverly rendered; ganas sculpted in varying states of relief and sizes with their accessories, limbs, and torsos carefully angled, contribute to a sense that the attendants and Durga’s lion are in the process of emerging in force from the background. This exquisite engineering of space and volume has done much to convey the excitement of the scene—the lion appears to burst into battle and we can almost hear a ferocious roar escape his open mouth. The forward thrust of the winning side is facilitated by an arc at roughly the center of the panel.

Follow the curve of Durga’s bow to the torso of the falling figure with a shaven head to the pose of the kneeling warrior whose sword that falling figure is about to meet.

Dressed like the goddess in a dhoti and kucha bandha and with some jewelry, the warrior mirrors the calm and confident expression of the goddess. Individuality and strength in battle is portrayed in her magnificently rendered stomach.

The battle turns

The left knee of the kneeling warrior disappears behind the enormous foot of Mahishasura, which remains firmly pointed in the direction of the goddess’s camp; in the mind of the buffalo demon, the fight may yet be won. This hope is represented vividly: affected by the onslaught, Mahishasura’s left leg bends to flee, but he remains steady, holding his heavy club with both hands to continue the fight. He is dressed in princely attire with a dhoti and jewelry and his sharp buffalo horns sit beneath a crown. Mahishasura’s status is further emphasized with a parasol, although it is unclear which of his attendants carries that attribute over his head.

Just as the artists angled, foreshortened, and positioned the goddess’s entourage to convey the impression that the army was rushing into battle, the same devices are employed to foreshadow the failure of the demon army. Mahishasura’s bent knee, the elbow of the fallen figure behind him, and the seated pose of the collapsed soldier, angle away from the panel and, indeed, the temple. The expression of abject horror recorded on the face of the foreshortened figure of a fallen soldier as he lies dangerously close to his master’s giant foot similarly signals that the end of the battle nears.

Unequivocal triumph

In the devotional text Devi Mahatmya referred to above, the goddess manifests from within male gods and destroys demons with the weapons that she receives from those gods. By virtue of her gender and her beauty, she catches Mahishasura by surprise, for he does not believe that she is capable of his destruction. At Mamallapuram, the sculptors followed the standard formulae of artistic treatises in their depiction of the goddess as a model of perfect womanhood. And in Durga’s modest size, relative to that of the buffalo demon, they signaled the apparent impossibility of Mahishasura’s defeat.

But the masterful storytellers at Mamallapuram also made certain that there was not a doubt that the mighty Mahishasura would fall. In the assured attitude of the goddess and the ease with which she overwhelms Mahishasura and his army, we are reminded that without the goddess, all would have been lost.

Notes:

- For more on shakti and Chandika see Wendy Doniger, The Hindus: An Alternative History (New York: Penguin Group, 2009), pp. 387 – 392.

- While this penultimate moment is better described according to the scholars Vidya Dehejia and Gary Tartakov as Mahishasurasainyavadha (“the slaying of the armies of Mahishasura”), we follow the popular designation of Mahishasuramardini here. See Vidya Dehejia and Gary Tartakov, “Sharing, Intrusion, and Influence: The Mahiṣāsuramardinī Imagery of the Calukyas and the Pallavas,” Artibus Asiae, Vol. 45, No. 4 (1984), p. 291.

- The unfinished state did not affect the religious function of this site. A study of the phenomenon of unfinished shrines and an examination of the difference between usable and unusable unfinished monuments was recently published by art historian Vidya Dehejia and sculptor Peter Rockwell. See: The Unfinished: Stone Carvers at Work on the Indian Subcontinent (New Delhi: Roli Books, 2016).

- If depicted, the arrow would have crossed Durga’s face as she took aim at Mahishasura. It is left uncarved in an effort, on the part of the sculptor, not to obscure the face of the goddess.

- Dehejia and Tartakov, “Sharing,” p. 289.

Chola dynasty

Queen or goddess?

by DR. EMMA NATALYA STEIN, FREER GALLERY OF ART and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Queen Sembiyan Mahadevi as the Goddess Parvati, Chola Dynasty (reign of Queen Sembiyan Mahadevi), 10th century, bronze, 107.3 x 33.4 x 25.7 cm (Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, F1929.84) Speakers: Dr. Emma Natalya Stein, Curatorial Fellow for Southeast Asian Art, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Additional resources

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

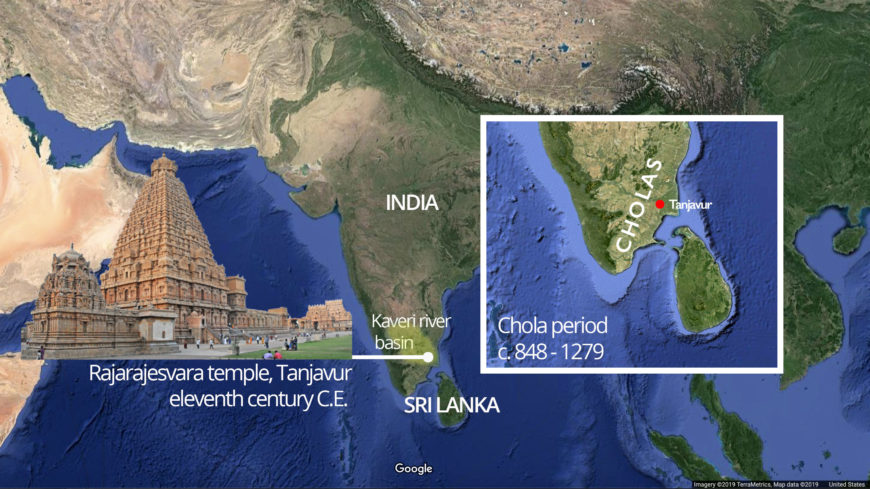

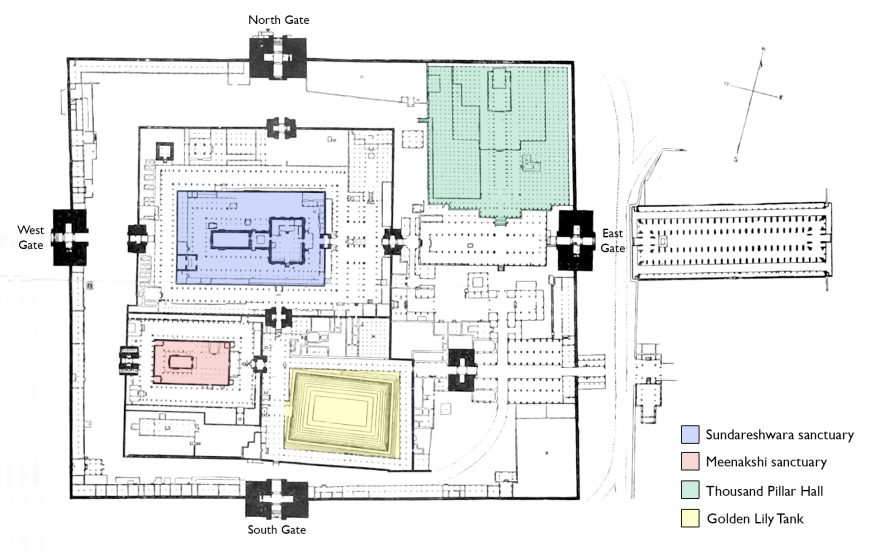

Rajarajesvara temple, Tanjavur

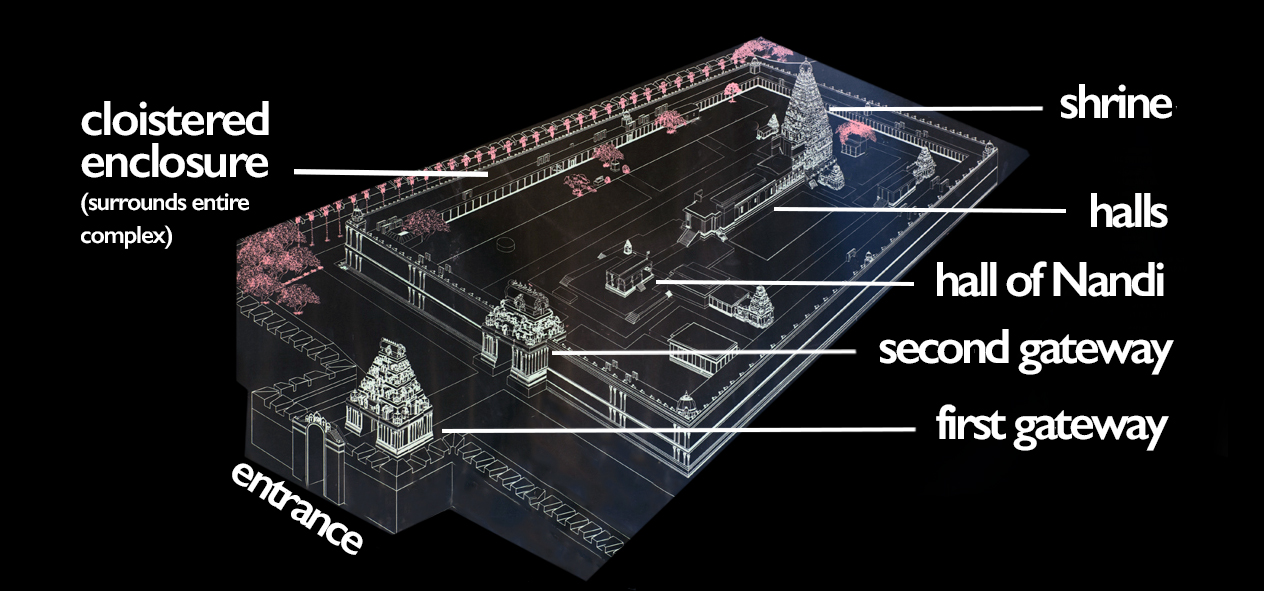

To see the Hindu god Shiva in the Rajarajesvara temple complex in Tanjavur, we must enter two impressive gateways, walk into a cloistered courtyard, past an enormous stone bull, climb the stairs of the largest temple, and proceed through halls filled with beautifully carved pillars. Then, straight ahead, at the far end of the interior of the temple is the monumental Shiva linga — an aniconic (non-representational) emblem of the deity. Above the linga, a tall superstructure rises, reaching a height of 216 feet from the ground. This is the symbolic core of the Rajarajesvara temple, the city of Tanjavur, and the Chola empire.

The Rajarajesvara temple was built by one of the most successful rulers of the medieval period, Rajaraja Chola I. Tanjavur was the capital of the Cholas, an empire that ruled much of present-day South India from c. 848 until 1279. Although this region had been home for the Cholas for generations — they are even mentioned in an Ashokan edict from the third century B.C.E. [1] — it is the family of Chola rulers who emerged in the ninth century who would leave an indelible mark on the history of art and architecture.

The Cholas’ prosperity was largely due to their investment in harnessing water in the Kaveri river basin for agricultural and irrigation projects and turning vast areas into cultivable land. This, alongside their increased commercial endeavors and active participation in Indian Ocean maritime trade contributed to a thriving empire.

Rajarajesvara temple is emblematic of the Cholas’ might and prosperity at the turn of the eleventh century. At that point Chola territory had expanded to include much of south India and parts of Sri Lanka. Chola influence also extended to Southeast Asia where they had established profitable commercial interests with the kingdom of Srivijaya in Indonesia.

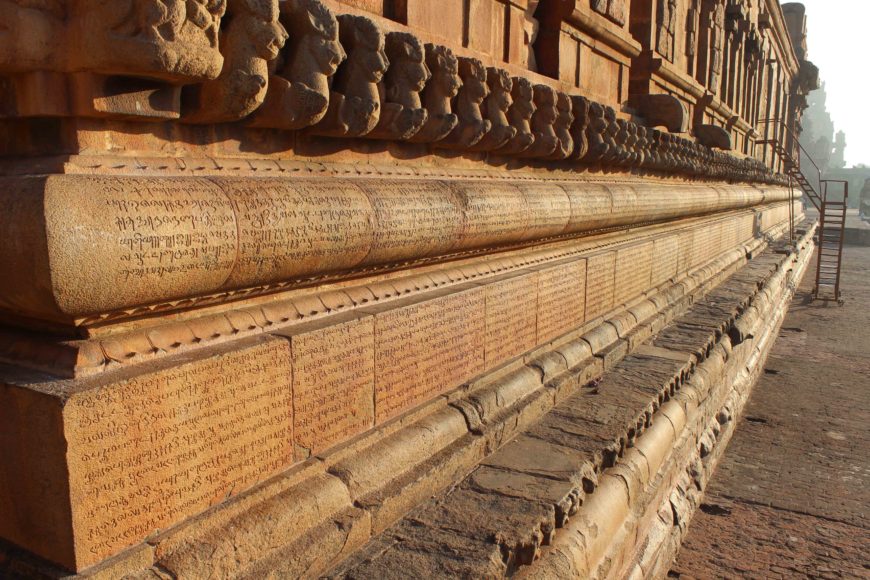

Records in stone

The immense skill of the Rajarajesvara temple’s architect, builders, and sculptors is immediately apparent from the size and the grandeur of the temple. Also clearly evident is the significant amount of resources — people, time, and stone — that was involved.

The temple preserves records in the form of inscriptions that are carved on its stone base. The inscriptions provide a wealth of information; the gifts received by the temple in the form of jewelry, processional bronze images for use in ritual and festivals, and endowments given for the maintenance of temple activities are documented.

Inscriptions also provide details on the conduct of rituals, the allocation of resources owned by the temple, and mention the names of donors. The temple received contributions from the king, queens, ministers and feudatories, as well as the temple’s priests and administrators.

Royal, sacred, and cultural center

The Rajarajesvara temple was located within a royal and sacred complex. The king’s palace, which was nearby, doesn’t survive. The temple’s impressive height (it was the largest of its kind at the time) and wealth must have impressed Tanjavur’s citizenry. The temple’s economic influence was considerable — many people tended the lands owned by the temple, and the temple employed hundreds as dancers, priests, accountants, and administrators. Rajarajesvara temple was also an influential cultural center with performances of dance and music, as well as a place of spiritual education and discourse.

The Cholas were not new to temple building. Inscriptions on the walls of earlier temples tell us that the Chola queen Sembiyan Mahadevi was an enthusiastic temple builder. She even rebuilt older brick temples in stone, making sure that the inscriptions of those temples were re-inscribed on their rebuilt walls.

There was no comparable Chola antecedent for the monumental size of the Rajarajesvara temple (see its relative difference in scale from earlier temples in the image above). Rajarajesvara stands as testament to the unhesitating confidence of those who dreamed, conceptualized, and engineered the temple.

A grand entrance

Just past a moat, a large and impressive gopura (gateway) stands as the first entryway into the sacred complex (see plan above). A short walk reveals a second gopura with two massive guardian figures carved in high relief, flanking the entryway. Guardians are a common feature in Indian temple architecture. They are protective figures who safeguard portals to the gods and are often portrayed as intimidating. The guardian figures here are large, multi–armed and hold a mace (club) — attributes that highlight their role as divine guardians. The guardians are dynamic and animated; they are adorned with elaborate jewelry and clothing, have raised eyebrows and sharp fangs, and they rest an arm and a foot on their weapon as they stand confidently and at the ready to protect.

View of the second gopura (entryway) into the Rajarajesvara temple complex

The second gopura (gateway) is part of a tall cloister (covered walkway) that surrounds the temple enclosure. The gopura is adorned with relief carvings below the guardians and sculptures on the superstructure above. These are smaller in scale relative to the guardian figures.

Within the enclosure, a large monolithic stone bull is dressed with jewelry and a necklace of bells. This is Nandi, Shiva’s vahana. He sits with his back to the gopura, facing the main temple structure (which houses Shiva). Nandi and the open pillared stone canopy over him are dated to the sixteenth century or later, although the platform upon which Nandi is seated may be earlier. As a living temple (a temple that is an active site for worship), Rajarajesvara continued to receive gifts (such as funds for a new Nandi and canopy) long after the temple’s construction.

Dravida style

There are multiple Indian temple architectural styles, the most common of which are dravida and nagara. The dravida style of temple architecture is more frequently adopted in south India, while temples in north India are more often built in the nagara style. Rajarajesvara is built in the dravida style.

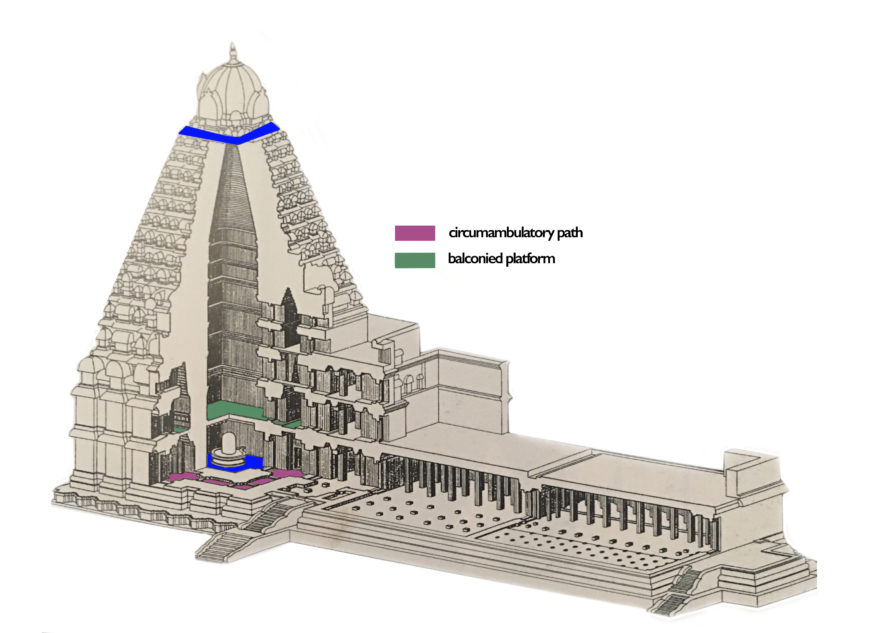

The main structure is comprised of the shrine and two pillared halls that are attached and arranged one following the other. The hall closer to the entrance of the structure is known as the mukhamandapa (front hall) and the hall nearest to the shrine is known as the mahamandapa (great hall). At the center of the shrine is the garbagriha (sanctum) — the chamber of god. Above the shrine is a pyramidal superstructure known as the vimana.

Larger than life-size images of Shiva within decorated niches and framing pilasters line the exterior walls of the shrine on two levels. In Hindu belief, gods have myriad manifestations; each form represents a particular purpose or legend, but always represents the one and the same supreme being. Doorways pierce the center of the rows of figures.

The images of Shiva on the lower level show the deity in a number of different embodiments. Six niches on the upper level depict Shiva as Tripurantaka — a form in which Shiva defeated the three cities of the asuras (malevolent adversaries of the gods). Art historian Vidya Dehejia has suggested that the emphatic repetition of Tripurantaka, although in different poses, was likely significant to Rajaraja and his identity as conqueror. [2]

View of the rear wall (west) of the Rajarajesvara temple shrine. Note the various forms of Shiva and the two guardian figures (flanking the doorway) on the lower level and the images of Shiva as Tripurantaka on the upper level.

The exterior wall of the two halls in front of the shrine differ in their sculptural program. Here we find pierced stone windows, gods in decorated niches and pilasters, and incomplete carvings. Common to the walls of both the shrine and the two halls are a pair of continuous architectural courses of yalis (mythical creatures) who serve both a decorative and apotropaic (protective) function.

View of the exterior of the temple halls (north) at Rajarajesvara

The main entrance into the structure is at its east end (facing Nandi the bull). The entryway is reached via two flights of stairs – one each at the north and south ends of a platform. The pillars on that platform and the frontal stairs are later additions. [3] There are also two sets of stairs and entrances flanked by guardians at the north and south sides of the building closer to the shrine.

View of the entrance (east) into the main temple at Rajarajesvara. The frontal stairs and the pillars up front are later additions.

Shrine and superstructure

Surrounding the garbagriha (sanctum) at the center of the shrine (see the plan below) is a circumambulatory path with wall murals (painted with a wet lime-wash and mineral pigments) that celebrate the legends of Shiva. The ceiling of this circumambulatory path serves as the floor of a balconied platform above. Carved in low relief on the balcony’s railing are images of dancing Shiva. [4] From here, tapered and corbeled slabs of masonry lend support to the remaining upper levels of the hollow vimana. [5]

The vimana is decorated in horizontal registers on the exterior and at its very top carries a crowning piece known as the stupi. Above the stupi stands the kalasha, a pot-shaped finial that is made from copper.

The monumental linga — roughly 12 feet tall, beautifully adorned with flowers and glistening from the gold and the light of oil lamps — is immediately awe-inspiring. Only priests can enter the sanctum; devotees stand just outside the sanctum for darshan (to see and be seen by god) and for puja.

New heights

The temple’s architect and builders would have followed the general rules prescribed in treatises for the design of the sacred complex and its sculptures. Treatises on art and architecture were developed over centuries of temple building and offered precise instructions on appropriate siting, layout, and measurements for temple construction and ornamentation. Even with that guidance, the enormity of this project will have made for a complex undertaking.

More than a thousand years since it was built, there is little doubt that Rajarajesvara temple holds an important place in the legacy of the Cholas. By building a temple so incredible, Rajaraja Chola I aptly epitomized both his triumphant reign as king and gratitude for his achievements. And he affirmed — for all to see — the religious benediction of Shiva at the heart of his empire.

Notes:

[1] See the 2nd major rock edict of Ashoka, for example, in Romila Thapar, Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 251.

[2] Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon, 1997), p. 214–6.

[3] K.R. Srinivasan, “Middle Colanadu style, c. A.D. 1000–1078; Colas of Tanjavur: Phase II.” In Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture: South India Lower Dravidadesa, 200 B.C.– A.D. 1324, edited by Michael W. Meister (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983), p. 239.

[4] Dehejia, ibid., pp. 217-8.

[5] Srinivasan, ibid., pp. 238.

Additional resources:

Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon, 1997), pp. 207–24.

Vidya Dehejia, Art of the Imperial Cholas (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990).

Partha Mitter, Indian Art (London: Oxford, 2001), pp. 57–9.

K.R. Srinivasan, “Middle Colanadu style, c. A.D. 1000–1078; Colas of Tanjavur: Phase II.” In Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture: South India Lower Dravidadesa, 200 B.C.– A.D. 1324, edited by Michael W. Meister (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983), pp. 234–41.

Romila Thapar, Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Shiva as Lord of the Dance (Nataraja)

A sacred object out of context

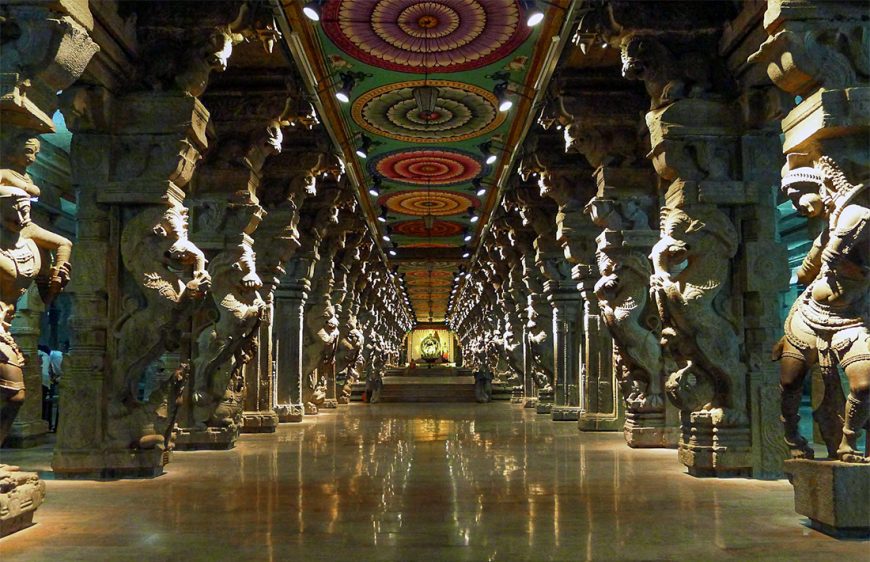

The art of medieval India, like the art of medieval Europe, was primarily in the service of religion. The devotee’s spiritual experience was enhanced by meditation inspired by works of art and architecture. Just as the luminous upper chapel of the Sainte Chapelle dazzled and overwhelmed worshipers in France, the looming bronze statues of Shiva and Parvati in, for example, the inner halls of the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai, in south India would have awed a Hindu devotee.

It is important to keep in mind that the bronze Shiva as Lord of the Dance (“Nataraja”—nata meaning dance or performance, and raja meaning king or lord), is a sacred object that has been taken out of its original context—in fact, we don’t even know where this particular sculpture was originally venerated. In the intimate spaces of the Florence and Herbert Irving South Asian Galleries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Shiva Nataraja is surrounded by other metal statues of Hindu gods including the Lords Vishnu, Parvati, and Hanuman. It is easy to become absorbed in the dark quiet of these galleries with its remarkable collection of divine figures, but it is important to remember that this particular statue was intended to be movable, which explains its moderate size and sizeable circular base, ideal for lifting and hoisting onto a shoulder.

Made for mobility

From the eleventh century and onwards, Hindu devotees carried these statues in processional parades as priests followed chanting prayers and bestowing blessings on people gathered for this purpose. Sometimes the statues would be adorned in resplendent red and green clothes and gold jewelry to denote the glorious human form of the gods. In these processions The Shiva Nataraja may have had its legs wrapped with a white and red cloth, adorned with flowers, and surrounded by candles. In a religious Hindu context, the statue is the literal embodiment of the divine. When the worshiper comes before the statue and begins to pray, faith activates the divine energy inherent in the statue, and at that moment, Shiva is present.

A bronze Shiva

Shiva constitutes a part of a powerful triad of divine energy within the cosmos of the Hindu religion. There is Brahma, the benevolent creator of the universe; there is Vishnu, the sagacious preserver; then there is Shiva, the destroyer. “Destroyer” in this sense is not an entirely negative force, but one that is expansive in its impact. In Hindu religious philosophy all things must come to a natural end so they can begin anew, and Shiva is the agent that brings about this end so that a new cycle can begin.

The Metropolitan Museum’s Shiva Nataraja was made some time in the eleventh century during the Chola Dynasty (ninth-thirteenth centuries C.E.) in south India, in what is now the state of Tamil Nadu. One of the longest lasting empires of south India, the Chola Dynasty heralded a golden age of exploration, trade, and artistic development. A great area of innovation within the arts of the Chola period was in the field of metalwork, particularly in bronze sculpture. The expanse of the Chola empire stretched south-east towards Sri Lanka and gave the kingdom access to vast copper reserves that enabled the proliferation of bronze work by skilled artisans.

During this period a new kind of sculpture is made, one that combines the expressive qualities of stone temple carvings with the rich iconography possible in bronze casting. This image of Shiva is taken from the ancient Indian manual of visual depiction, the Shilpa Shastras (The Science or Rules of Sculpture), which contained a precise set of measurements and shapes for the limbs and proportions of the divine figure. Arms were to be long like stalks of bamboo, faces round like the moon, and eyes shaped like almonds or the leaves of a lotus. The Shastras were a primer on the ideals of beauty and physical perfection within ancient Hindu ideology.

A dance within the cosmic circle of fire

Here, Shiva embodies those perfect physical qualities as he is frozen in the moment of his dance within the cosmic circle of fire that is the simultaneous and continuous creation and destruction of the universe. The ring of fire that surrounds the figure is the encapsulated cosmos of mass, time, and space, whose endless cycle of annihilation and regeneration moves in tune to the beat of Shiva’s drum and the rhythm of his steps.

In his upper right hand he holds the damaru, the drum whose beats syncopate the act of creation and the passage of time.

His lower right hand with his palm raised and facing the viewer is lifted in the gesture of the abhaya mudra, which says to the supplicant, “Be not afraid, for those who follow the path of righteousness will have my blessing.”

Shiva’s lower left hand stretches diagonally across his chest with his palm facing down towards his raised left foot, which signifies spiritual grace and fulfillment through meditation and mastery over one’s baser appetites.

In his upper left hand he holds the agni (image left), the flame of destruction that annihilates all that the sound of the damaru has drummed into existence.

Shiva’s right foot stands upon the huddled dwarf, the demon Apasmara, the embodiment of ignorance.

Shiva’s hair, the long hair of the yogi, streams out across the space within the halo of fire that constitutes the universe. Throughout this entire process of chaos and renewal, the face of the god remains tranquil, transfixed in what the historian of South Asian art Heinrich Zimmer calls, “the mask of god’s eternal essence.”

Beyond grace there is perfection

The supple and expressive quality of the dancing Shiva is one of the touchstones of South Asian, and indeed, world sculpture. When the French sculptor Auguste Rodin saw some photographs of the eleventh century bronze Shiva Nataraja in the Madras Museum around 1915, he wrote that it seemed to him the “perfect expression of rhythmic movement in the world.” In an essay he wrote that was published in 1921 he wrote that the Shiva Nataraja has “what many people cannot see—the unknown depths, the core of life. There is grace in elegance, but beyond grace there is perfection.” The English philosopher Aldous Huxley said in an interview in 1961 that the Hindu image of god as a dancer is unlike anything he had seen in Western art. “We don’t have anything that approaches the symbolism of this work of art, which is both cosmic and psychological.”

The eloquent bronze statue of the Shiva Nataraja, despite the impact of its formal beauty on Rodin who knew little of its background, is incomplete without an understanding of its symbolism and religious significance. Bronzes of the Chola period such as Shiva as Lord of the Dance (Nataraja) arose out of a need to transmute the divine into a physical embodiment of beauty.

Additional Resources:

This sculpture at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Shiva Nataraja from the Smithsonian

This sculpture on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Hinduism and Hindu Art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Chandella dynasty

Sacred space and symbolic form at Lakshmana Temple, Khajuraho (India)

Ideal female beauty

Look closely at the image to the left. Imagine an elegant woman walks barefoot along a path accompanied by her attendant. She steps on a thorn and turns—adeptly bending her left leg, twisting her body, and arching her back—to point out the thorn and ask her attendant’s help in removing it. As she turns the viewer sees her face: it is round like the full moon with a slender nose, plump lips, arched eyebrows, and eyes shaped like lotus petals. While her right hand points to the thorn in her foot, her left hand raises in a gesture of reassurance.

Images of beautiful women like this one from the northwest exterior wall of the Lakshmana Temple at Khajuraho in India have captivated viewers for centuries. Depicting idealized female beauty was important for temple architecture and considered auspicious, even protective. Texts written for temple builders describe different “types” of women to include within a temple’s sculptural program, and emphasize their roles as symbols of fertility, growth, and prosperity. Additionally, images of loving couples known as mithuna (literally “the state of being a couple”) appear on the Lakshmana temple as symbols of divine union and moksha, the final release from samsara (the cycle of death and rebirth).[1]

The temples at Khajuraho, including the Lakshmana temple, have become famous for these amorous images—variations of which graphically depict figures engaged in sexual intercourse. These erotic images were not intended to be titillating or provocative, but instead served ritual and symbolic function significant to the builders, patrons, and devotees of these captivating structures.[2]

Chandella rule at Khajuraho

The Lakshmana temple was the first of several temples built by the Chandella kings in their newly-created capital of Khajuraho. Between the tenth and thirteenth centuries, the Chandellas patronized artists, poets, and performers, and built irrigation systems, palaces, and numerous temples out of sandstone. At one time over 80 temples existed at this site, including several Hindu temples dedicated to the gods Shiva, Vishnu, and Surya.[3] There were also temples built to honor the divine teachers of Jainism (an ancient Indian religion). Approximately 30 temples remain at Khajuraho today.

The original patron of the Lakshmana temple was a leader of the Chandella clan, Yashovarman, who gained control over territories in the Bundelkhand region of central India that was once part of the larger Pratihara Dynasty. Yashovarman sought to build a temple to legitimize his rule over these territories, though he died before it was finished. His son Dhanga completed the work and dedicated the temple in 954 C.E.

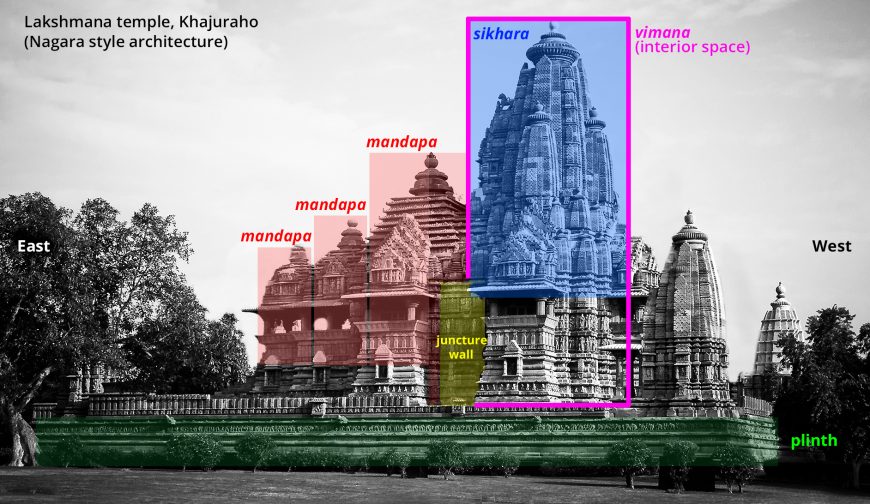

Nagara style architecture

The central deity at the Lakshmana temple is an image of Vishnu in his three-headed form known as Vaikuntha[4] who sits inside the temple’s inner womb chamber also known as garba griha (above)—an architectural feature at the heart of all Hindu temples regardless of size or location. The womb chamber is the symbolic and physical core of the temple’s shrine. It is dark, windowless, and designed for intimate, individualized worship of the divine—quite different from large congregational worshipping spaces that characterize many Christian churches and Muslim mosques.

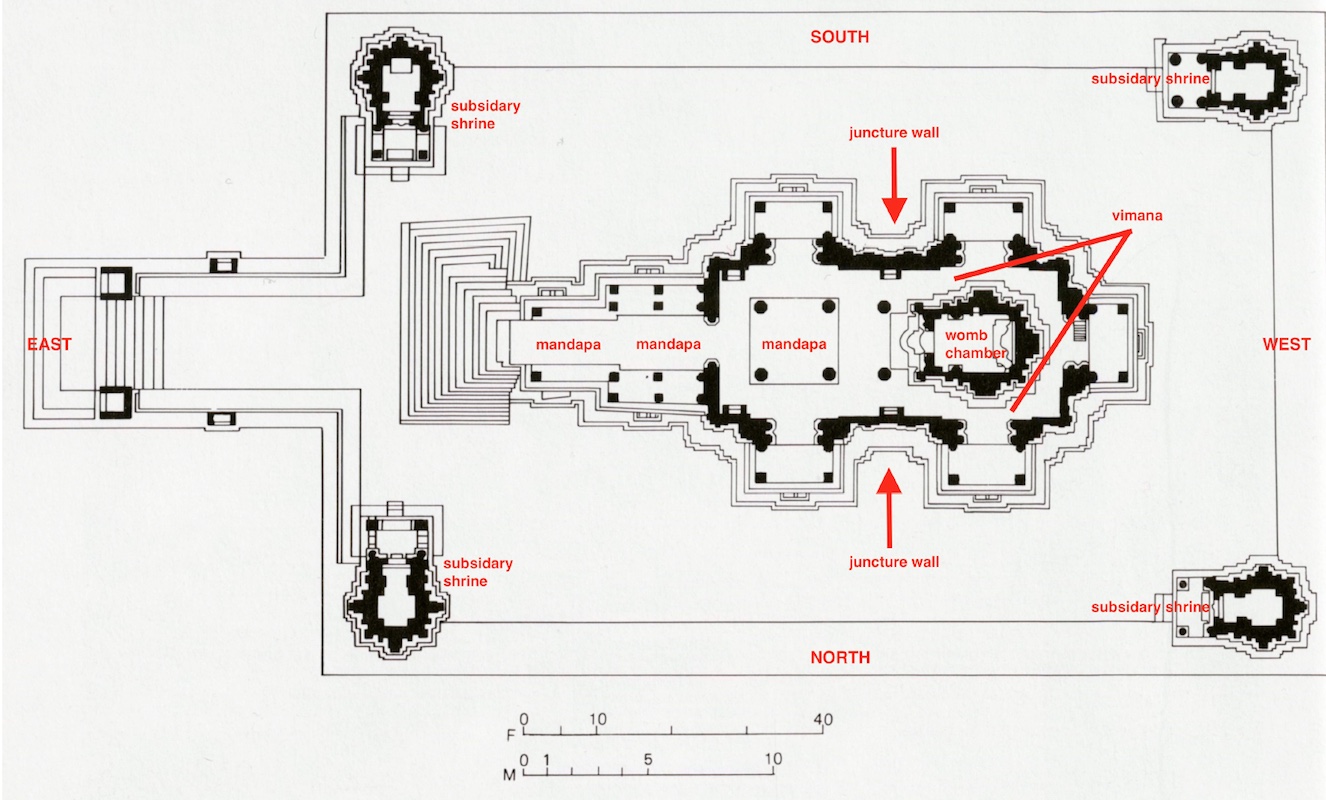

The Lakshmana Temple is an excellent example of Nagara style Hindu temple architecture.[5] In its most basic form, a Nagara temple consists of a shrine known as vimana (essentially the shell of the womb chamber) and a flat-roofed entry porch known as mandapa. The shrine of Nagara temples include a base platform and a large superstructure known as sikhara (meaning mountain peak), which viewers can see from a distance.[6] The Lakshmana temple’s superstructure appear like the many rising peaks of a mountain range.

Approaching the divine

Devotees approach the Lakshamana temple from the east and walk around its entirety—an activity known as circumambulation. They begin walking along the large plinth of the temple’s base, moving in a clockwise direction starting from the left of the stairs. Sculpted friezes along the plinth depict images of daily life, love, and war and many recall historical events of the Chandella period (see image below and Google Street View).

Devotees then climb the stairs of the plinth, and encounter another set of images, including deities sculpted within niches on the exterior wall of the temple (view in Google Street View).

In one niche (left) the elephant-headed Ganesha appears. His presence suggests that devotees are moving in the correct direction for circumambulation, as Ganesha is a god typically worshipped at the start of things.

Other sculpted forms appear nearby in lively, active postures: swaying hips, bent arms, and tilted heads which create a dramatic “triple-bend” contrapposto pose, all carved in deep relief emphasizing their three-dimensionality. It is here —specifically on the exterior juncture wall between the vimana and the mandapa (see diagram above)—where devotees encounter erotic images of couples embraced in sexual union (see image below and here on Google Street View). This place of architectural juncture serves a symbolic function as the joining of the vimana and mandapa, accentuated by the depiction of “joined” couples.

Four smaller, subsidiary shrines sit at each corner of the plinth. These shrines appear like miniature temples with their own vimanas, sikharas, mandapas, and womb chambers with images of deities, originally other forms or avatars of Vishnu.

Following circumambulation of the exterior of the temple, devotees encounter three mandapas, which prepare them for entering the vimana. Each mandapa has a pyramidal-shaped roof that increases in size as devotees move from east to west.

Once devotees pass through the third and final mandapa they find an enclosed passage along the wall of the shrine, allowing them to circumambulate this sacred structure in a clockwise direction. The act of circumambulation, of moving around the various components of the temple, allow devotees to physically experience this sacred space and with it the body of the divine.

Notes:

[1] Mithuna figures appear on numerous Hindu temples and Buddhist monastic sites throughout South Asia from as early as the first century C.E. Maithuna is a related term that references figures depicted in the act of sexual intercourse.

[2] Some scholars suggest that these erotic images may be connected to Kapalika tantric practices prevalent at Khajuraho during Chandella rule. These practices included drinking wine, eating flesh, human sacrifice, using human skulls as drinking vessels, and sexual union, particularly with females who were given central importance (as the seat of the divine). The idea was that by indulging in the bodily and material world, a practitioner was able to overcome the temptations of the senses. However, these esoteric practices were generally looked down upon by others in South Asian society and accordingly very often were done in secrecy, which raises questions about the logic of including Kapalika-related images on the exterior of a temple for all to see. For a compelling discussion on the history of popular and scholarly perception of the nude figures at Khajuraho, see Tapati Guha-Thakurta’s essay referenced below.

[3] There is also at least one temple at Khajuraho, the Chausath Yogini Temple, dedicated to the Hindu Goddess Durga and 64 (“chausath”) of her female attendants known as yoginis. It was built by a previous dynasty who ruled in the area before the Chandella kings rose to power.

[4] The original Vaikuntha at Lakshmana temple was itself politically significant: Yashovarman took it from the Pratihara overlord of the region. Susan Huntington indicates that the stone image currently on view at Lakshmana temple, while indeed a form of Vaikuntha, is not in fact the original (metal) image which Yashovarman appropriated from the Pratihara ruler. Appropriating another ruler’s family deity as a political maneuver was a widespread practice throughout South Asia. For more on this practice, see the work of Finbarr B. Flood, Objects of Translation: Material Culture and Medieval ‘Hindu-Muslim’ Encounter (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), particularly Chapter 4. A similar Vaikuntha image now appears in the central shrine of the Lakshmana temple and is notable for its depiction of the deity’s three heads with a human face at the front (east), a lion’s face on the left (south), and a boar’s face on the right (north)—the latter two of which are now badly damaged. An implied, though not visible fourth face is that of a demon’s head at the rear of the image (west-facing) which has led some scholars to identify this form as Chaturmurti or four-faced.

[5] In general, there are two main styles of Hindu temple architecture: the Nagara style, which dominates temples from the northern regions of India, and the Dravida style, which appears more often in the South.

[6] The base platform is sometimes known as pitha, meaning “seat.” A flattened bulb-shaped topper known as amalaka appears at the top of the superstructure or sikhara. The amalaka is named after the local amla fruit and is symbolic of abundance and growth.

Additional resources:

Beliefs Made Visible: Hindu Temples in South Asia

Hinduism and Buddhism, an Introduction

Ganesha in a Temple Niche from the Asian Art Museum

Hindu Temples from the Asian Art Museum

Vidya Dehejia, “Reading Love Imagery on the Indian Temple,” Love in Asian Art and Culture (Washington, D.C.: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution), pp. 97-112.

Vidya Dehejia, The Body Adorned: Dissolving Boundaries Between Sacred and Profane in India’s Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009).

Tapati Guha-Thakurta, “Art History and the Nude: On Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality in Contemporary India,” in Monuments, Objects, Histories: Institutions of Art in Colonial and Postcolonial India (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

Susan L. Huntington, The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain (New York: Weatherhill, 1985), 466-477.

Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vols. 1 and 2 (Calcutta: University of Calcutta, 1946), pp. 131-144 and 346-347.

Michael Meister, “Juncture and Conjuncture: Punning and Temple Architecture,” Artibus Asiae, Vol. 41, No. 2/3 (1979), pp. 226-234.

The Delhi Sultanate

The Qutb complex and early Sultanate architecture

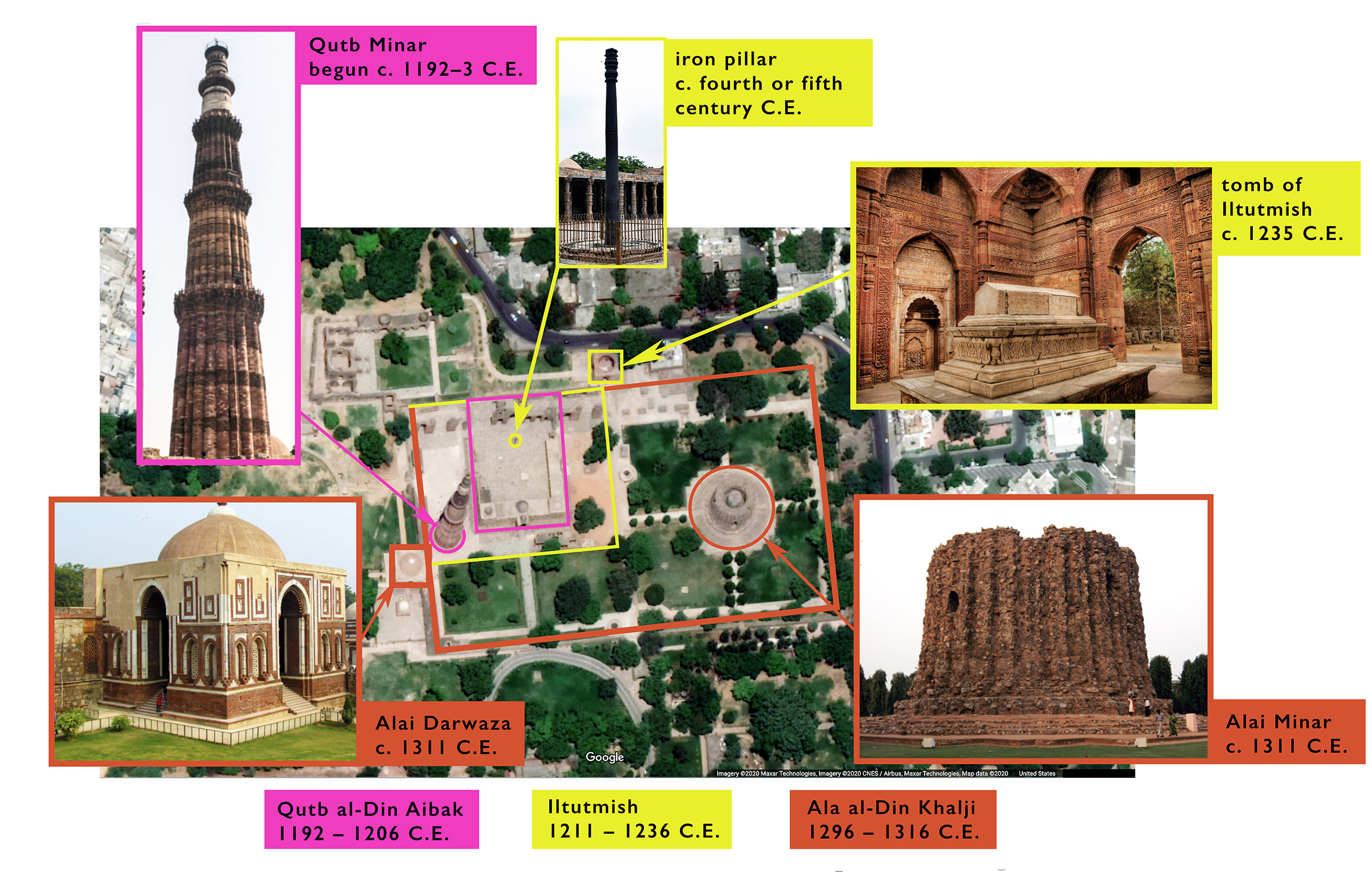

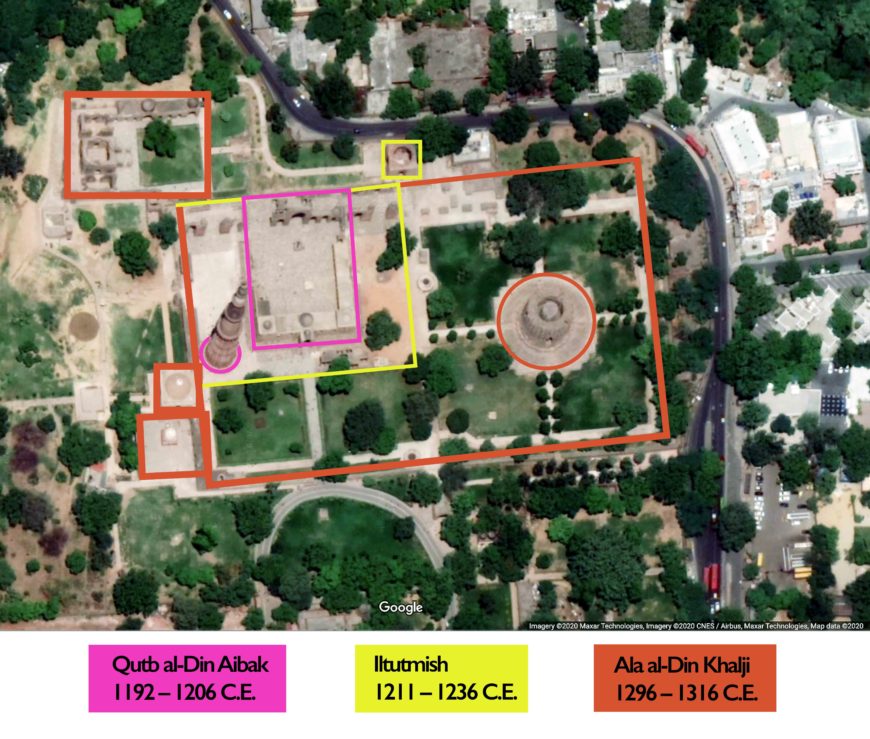

Layers of cultural, religious, and political history converge in the Qutb archaeological complex in Mehrauli, in Delhi, India. In its beautiful gateways, tombs, lofty screens, and pillared colonnades is a record of a centuries-long history of artistic vision, building techniques, and patronage. At the heart of the Qutb complex is a twelfth century mosque— an early example in the rich history of Indo-Islamic art and architecture.

The Qutb mosque is important for our understanding of the early part of the Delhi Sultanate (1206 – 1526), a period when new rulers would seek to cement their authority and legitimacy as kings in northern India. “Delhi Sultanate” is a collective term that refers to the Turko-Islamic dynasties that ruled, one after the other, from Delhi. [1] The monuments discussed in this essay were built by the three earliest rulers of the Sultanate. [2]

In addition to the mosque, this essay discusses the following structures in the Qutb complex of monuments:

- the iron pillar

- Qutb Minar

- the tomb of Iltutmish

- the Alai Darwaza

- and the Alai minar

The first Sultan of the Delhi Sultanate

Before Qutb al-Din Aibak was the first sultan of the Delhi Sultanate, he was a Turkic military slave and a general in the army of the Ghurid dynasty of Afghanistan. He played an important role in conquering Delhi in 1192, as part of the territorial ambitions of the eleventh century Ghurid ruler Muhammad Ghuri.

As the Ghurid administrator in Delhi, Aibak oversaw the building of congregational mosques, including the Qutb mosque. The mosque is believed to have been built quickly as a matter of necessity—not only would the Ghurid forces have needed a place to pray, but a mosque was crucial for the proclamation of the name of the ruler during the weekly congregational prayer. In this context, such proclamations would have affirmed the legitimacy of Muhammad’s Ghuri’s right to rule.

Stylistic influences that define early Delhi Sultanate architecture

Islamic monuments in South Asia did not begin with the Delhi Sultanate; mosques were built when Islam was introduced in Sindh (in present-day Pakistan) in the eighth century as well as for Muslim merchants and communities who lived in various ports and towns across the subcontinent. Few of these structures have survived however and the Qutb mosque holds the distinction of being the oldest mosque in Delhi, an early example of Islamic architecture in India, and one that synthesizes Persian, Islamic, and Indian influences.

Qutb al-Din Aibak had come to India from Afghanistan and was familiar with its diverse architectural landscape. Afghanistan’s architecture in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries reflected both its pre-Islamic and Islamic history, as well as cultural exchange with Central Asia and India. Historians also describe the court of the Delhi Sultanate as Persianized, because it made use of the Persian language, literature, and Perso-Islamic art and architecture.

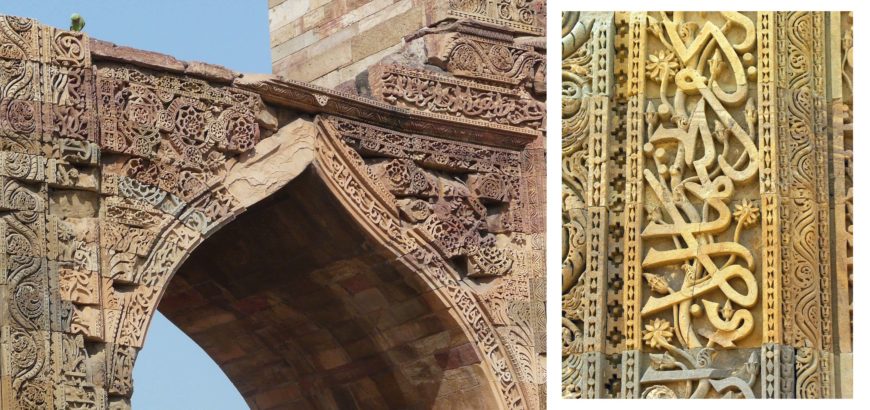

The architecture of the Delhi Sultanate is notable for its stylized decorative ornament which seamlessly incorporates features from Islamic artistic traditions such as arabesques (intertwining and scrolling vines), calligraphy, and geometric forms with Indian influences such as the floral motifs that adorn the calligraphy in the Qutb complex minar (tower) below.

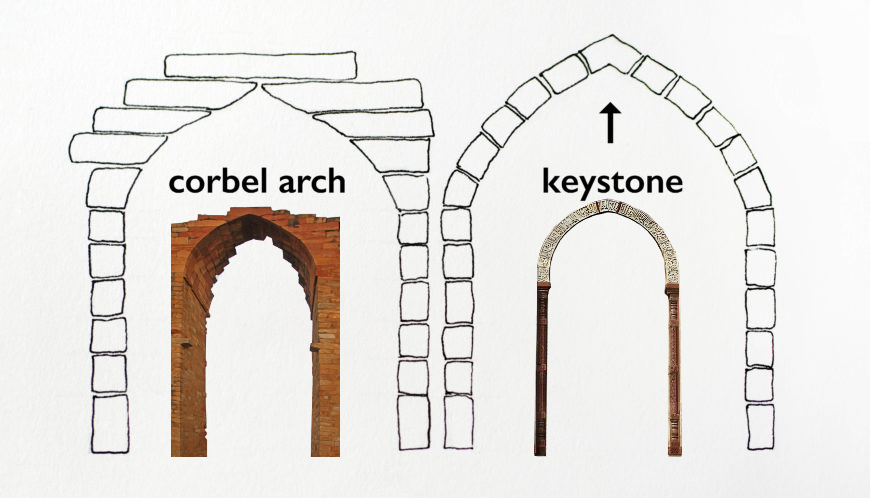

The hand of the Indian mason is discernible in the post and lintel and corbeling methods of construction employed in the earliest monuments in the complex, namely the Qutb mosque colonnade and prayer hall, its screen, and Iltutmish’s tomb. Later monuments at the Qutb complex (such as the fourteenth-century gateway Alai Darwaza) show a shift towards building techniques common in Islamic architecture outside of India. Arches in the Alai Darwaza, for instance, are not corbeled, but rather built with a series of wedge-shaped stones and a keystone.

Entrance into the Qutb mosque, begun c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi

The Qutb mosque and architectural re-use

The main entrance into the mosque today is on its east side. This arched doorway leads to a pillared colonnade and an open-air courtyard that is enclosed on three sides. Directly across from the main entrance, at the far end of the mosque, is an iron pillar, a monumental stone screen, and a hypostyle prayer hall.

Pillars, ceilings and stones from multiple older Hindu and Jain temples were reused in the construction of the colonnades surrounding the mosque’s open courtyard and in the prayer hall. Since the desired height for the colonnade did not match the height of older temple pillars, two or three pillars were stacked, one on top of the other, to reach the required elevation.

Indian temple pillars are often adorned with anthropomorphic figures of deities and divine beings, mythical zoomorphic, and apotropaic motifs, as well as decorative bands of flowers. A belief by the builders of this mosque in a proscription against the portrayal of living beings is evident in the removal of the faces carved in the older stonework. Other decorative motifs were left untouched, likely for their apotropaic and ornamental qualities.

Art historian Finbarr Flood has examined the complex motivations behind the re-use of stone at the Qutb mosque within a broad socio-political framework and has asked questions that go beyond the generally held view of religious iconoclasm (destruction of images). [3] Flood’s work has pointed to the probable use of spoliated (repurposed) stones from temples associated with the polities that were conquered by the Ghurid army (hence suggesting a political rather than religious motive), and has examined the important artistic interventions at the mosque (such as the meaning behind the addition of new stones that were carved to emulate temple pillars). [4]

In 1198 Aibak commissioned a monumental sandstone screen with five pointed arches that was built between the courtyard and the prayer hall. The screen was constructed with corbeled arches and is emphatically decorative with bands of calligraphy, arabesques, and other motifs, including flowers and stems that pop over, under, and through the stylized letters (see below).

An enduring legacy

In 1206, following the death of Muhammad Ghuri, Aibak declared himself ruler of the independent Mamluk (translated as “slave”) dynasty. Aibak’s efforts in building the Qutb mosque would endure longer than his tenure as sultan. Later rulers retained the mosque during expansions, indicating their reverence for the first mosque built in Delhi, and their regard for Aibak himself.

When Iltutmish became the new sultan of the Mamluk dynasty in 1211, he made Delhi the capital of the sultanate. During his reign, Iltutmish extended the screen and prayer hall on both sides of the west end of the Qutb mosque and added surrounding colonnades that, in effect, enclosed the original mosque. Iltutmish is also believed to have been responsible for the installation of the iron pillar in the mosque, a dhwaja stambha (ceremonial pillar) that dates to the fourth or fifth century and was originally installed in a Hindu temple.

The pillar has an inscription in the Sanskrit language that praises and eulogizes a ruler. In installing the pillar in the mosque and giving it pride of place, Iltutmish was following a tradition of previous rulers who appropriated such emblems of historic kingship to announce their legitimacy. In appropriating the pillar—and in effect the Qutb mosque as a whole—Iltutmish sought to affirm his political authority and legitimacy. [5]

Just as Iltutmish enclosed Aibak’s mosque with his additions, Ala al-Din Khalji, the ruler of the next Sultanate, would enclose the extension built by Iltutmish. Khalji had even grander plans, although his efforts were only partially realized (see annotated plan below).

The Qutb Minar

In 1192–93, soon after conquering Delhi, Aibak also began work on the Qutb Minar, the impressive 238 foot tall minaret (tower) of red and light sandstone for his Ghurid overlord. The minar’s tapering, fluted, and angular bands contribute to the soaring affect of the monument. Its balconies are decorated with muqarna style (three-dimensional honeycomb forms) corbels that allow us to imagine the expansive views of Delhi from each of its five stories. The minar is decorated with bands of calligraphy that are both historic (referencing Muhammad Ghuri) and religious.

Construction on the minar had only reached the height of its first story at the time of Aibak’s death in 1210. The minar would be completed by Iltutmish and its great height and beauty would became emblematic of the power of the Delhi Sultanate.

An open-air tomb

Iltutmish’s tomb, which the namesake commissioned during his reign, is located in the northwest corner of the Qutb complex, outside of the mosque’s courtyard. Constructed from new stone (that is, not spolia), this square tomb is relatively simple in its exterior decorative program, but its interior stuns with its overwhelming ornament. Tall pointed arches frame arched doorways and niches, and calligraphic inscriptions from the Quran, floral ornament, arabesques, and geometric patterns adorn the walls.

Although it has been suggested that the tomb is missing its dome, its absence may have been intentional, allowing light to bathe the marble grave marker. Like the ornament that surrounds the tomb’s interior, this light directs our focus to the center of the monument, below which lies Iltutmish’s burial chamber.

Like the Qutb mosque and screen, Iltutmish’s tomb was built in the post and lintel fashion and its arches were corbeled. In contrast, less than a hundred years later, arches in Ala al-Din Khalji’s monuments were constructed with a keystone at its summit.

Domed gateways

Ala al-Din Khalji, a fourteenth century ruler who conducted many campaigns to subjugate rivals and to increase his wealth, had plans to expand the Qutb complex substantially. Although he was largely unsuccessful in realizing these ambitions, a ceremonial gateway attributed to his patronage is one of the site’s most important monuments. It is the only remaining monumental gateway of four that are believed to have been built along the perimeter walls of the complex.

Known as the Alai Darwaza, the gateway is a square structure built in 1311. Like Iltutmish’s tomb, the gateway is built from new stone. The tall red base, the alternation of white marble and red sandstone ornament, and the latticed windows lend substantial grandeur to the gateway.

The arches in the Alai Darwaza are in the form of horseshoe arches (literally an arch in the form of a horseshoe); the same form is used to also ornament the squinches, i.e., the transition (at the corners of the structure) from the square base to the octagonal ceiling that helps receive the dome. The dome rests on the arches and squinches, in the fashion commonly found in contemporaneous Islamic architecture outside of India.

While building techniques changed from the corbeled arches of the Qutb mosque to the keystone-arches of the Alai Darwaza, there were also continuities. The use of Indic style architectural ornament (flowers, lotus buds, and bells), for example, remained an emphatic part of the sculptural vocabulary of Sultanate architecture.

Alai Minar

Ala al-Din also began construction of a minar that would have been considerably taller than the Qutb Minar, had it been completed—the unfinished base rises 80 feet in height. All that was built is the rubble core of the structure; the minar would have eventually been faced with stone, perhaps in a fashion and with adornment similar to that of the Qutb Minar.

The early sultans of the Delhi Sultanate employed architecture as a tool to announce, maintain, and advance their identity as rulers. Much like older monuments were appropriated in the construction of the Qutb mosque, subsequent sultans appropriated the Sultanate’s earliest work to advance their claims to legitimacy.

The Qutb complex today

The Qutb complex of monuments is now a popular tourist destination, a transformation that can be traced back to the nineteenth century when the grounds were redesigned to appeal to English colonial visitors. The monuments were surrounded by neatly manicured lawns, roads were diverted for the exclusive use of visitors, and enclosures were built to fashion a tranquil setting. Although the Qutb complex has been changed throughout its history, the vision of its original builders remain plainly transparent.

Many thanks to Dr. Marta Becherini for her comments on this essay.

Notes:

[1] The five dynasties of the Delhi Sultanate were: Mamluk (1206–90), Khalji (1290–1320), Tughlaq (1320–1414), Sayyid (1414–51), and Lodi dynasties (1451–1526).

[2] These were Qutb al-Din Aibak (ruled 1206–10) and Shams al-Din Iltutmish (r. 1211–36) of the Mamluk Sultanate, and Ala al-Din (r. 1296–1316) of the Khalji Sultanate.

[3] Flood has shown that the inscription referencing the use of stone from 27 temples in the mosque’s entrance is anachronistic to Aibak’s reign; it is hence not considered here. See Finbarr Barry Flood, “Appropriation as Inscription: Making History in the First Friday Mosque of Delhi.” In Reuse value [electronic resource] : spolia and appropriation in art and architecture from Constantine to Sherrie Levine, edited by Richard Brilliant and Dale Kinney (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), pp. 121-47.

[4] See Flood’s Objects of translation: material culture and medieval “Hindu-Muslim” encounter (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009); “Refiguring Iconoclasm in the early Indian mosque.” In Negating the Image: Case Studies in Iconoclasm, edited by Anne McClanan and Jeff Johnson (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), pp. 15–40; and “Appropriation as Inscription.”

[5] Flood, Objects, pp. 247-51.

References:

Catherine B. Asher and Cynthia Talbot, India before Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Aditi Chandra, “On Becoming a Monument: Landscaping, Views, and Tourists at the Qutb Complex,” in On the Becoming and Unbecoming of Monuments: Archaeology, Tourism and Delhi’s Islamic Architecture (1828-1963). University of Minnesota, 2011, pp. 16-70.

Finbarr Barry Flood, “Appropriation as Inscription: Making History in the First Friday Mosque of Delhi.” In Reuse value [electronic resource] : spolia and appropriation in art and architecture from Constantine to Sherrie Levine, edited by Richard Brilliant and Dale Kinney (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), pp. 121-47.

Finbarr Barry Flood, Objects of translation: material culture and medieval “Hindu-Muslim” encounter (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009).

Finbarr Barry Flood, “Refiguring Iconoclasm in the early Indian mosque.” In Negating the Image: Case Studies in Iconoclasm, edited by Anne McClanan and Jeff Johnson (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), pp. 15–40.

Street views:

Qutb mosque

Qutb Minar

View of Iltutmish’s tomb

Alai Darwaza

Alai Minar

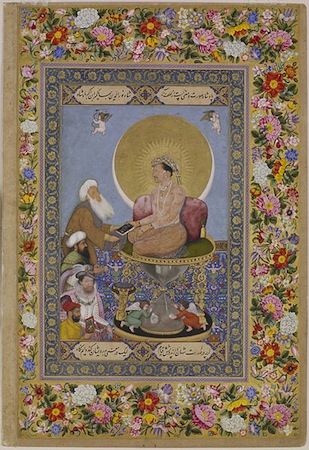

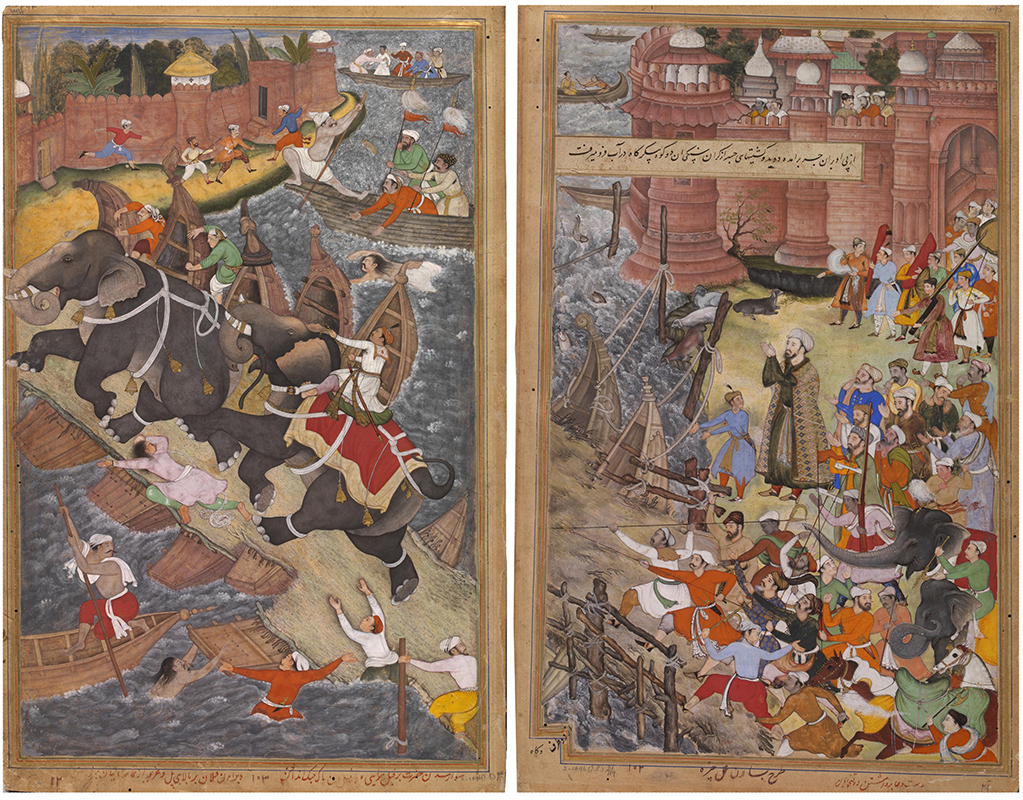

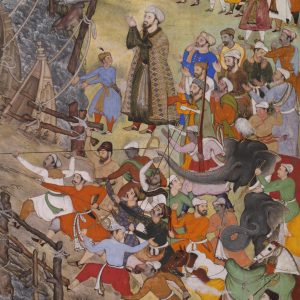

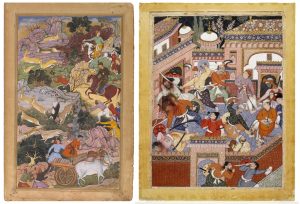

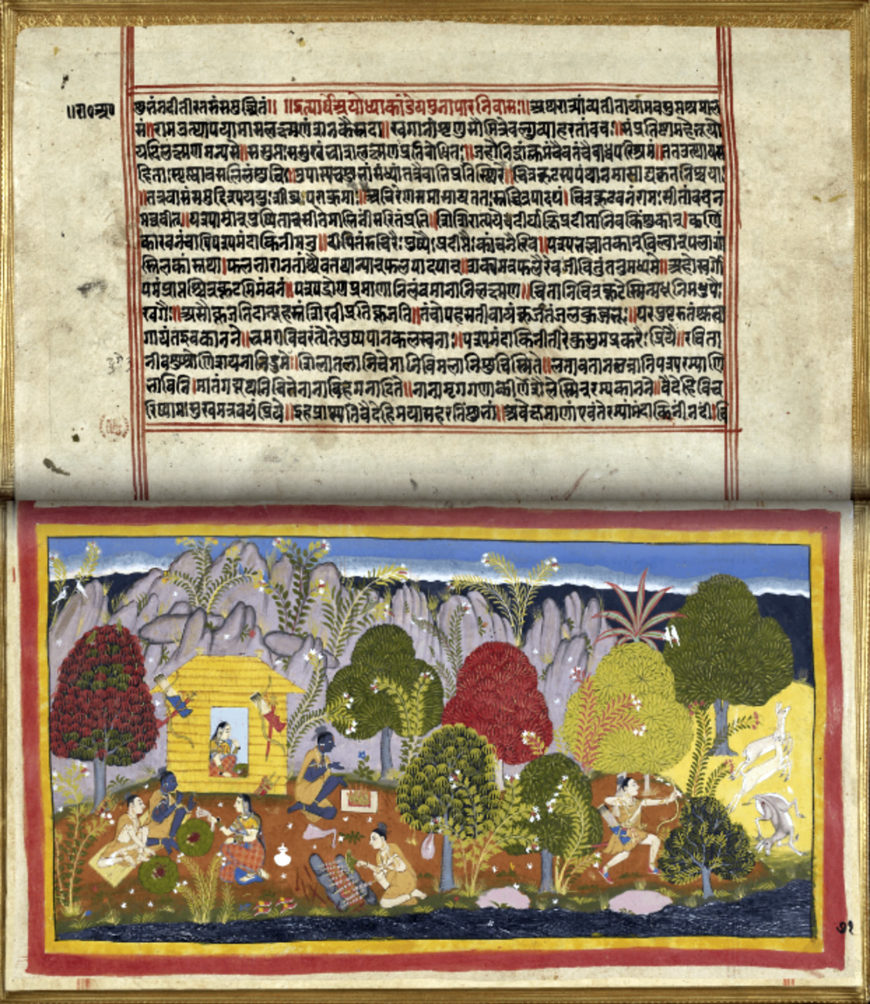

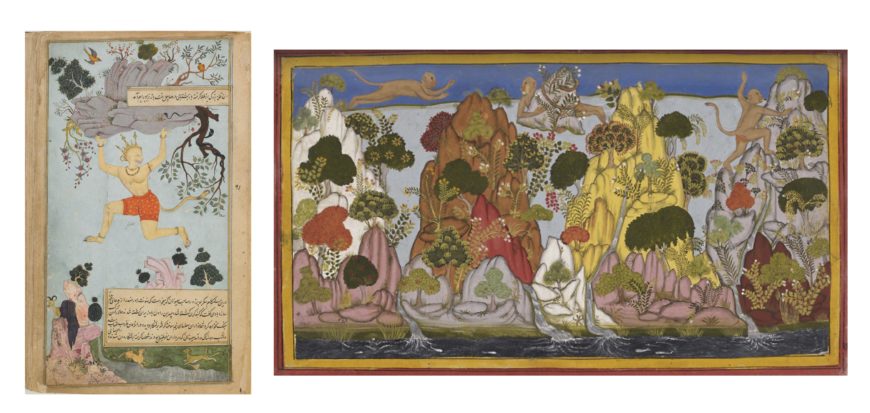

Art of the Mughal empire

Islam gained influence in India under the Mughals in the sixteenth century.

1526 - 1858

The Taj Mahal

Shah Jahan was the fifth ruler of the Mughal dynasty. During the third year of his reign, his favorite wife (known as Mumtaz Mahal), died due to complications arising from the birth of their fourteenth child. Deeply saddened, the emperor started planning the construction of a suitable, permanent resting place for his beloved wife almost immediately. The result of his efforts and resources was the creation of what was called the Luminous Tomb in contemporary Mughal texts and is what the world knows today as the Taj Mahal.

In general terms, Sunni Muslims favor a simple burial, under an open sky. But notable domed mausolea for Mughals (as well as for other Central Asian rulers) were built prior to Shah Jahan’s rule, so in this regard, the Taj is not unique. The Taj is, however, exceptional for its monumental scale, stunning gardens, lavish ornamentation, and its overt use of white marble.

The location

Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal in Agra, where he took the throne in 1628. First conquered by Muslim invaders in the eleventh century, the city had been transformed into a flourishing area of trade during Shah Jahan’s rule. Situated on the banks of the Yamuna River allowed for easy access to water, and Agra soon earned the reputation as a “riverfront garden city,” on account of its meticulously planned gardens, lush with flowering bushes and fruit-bearing trees in the sixteenth century.

Paradise on Earth

Entry to the Taj Mahal complex via the forecourt, which in the sixteenth century housed shops, and through a monumental gate of inlaid and highly decorated red sandstone made for a first impression of grand splendor and symmetry: aligned along a long water channel through this gate is the Taj—set majestically on a raised platform on the north end. The rectangular complex runs roughly 1860 feet on the north-south axis, and 1000 feet on the east-west axis.