7.8: Ancient Nubia and the Kingdom of Kush

- Page ID

- 125468

Ancient Nubia and the Kingdom of Kush, an introduction

by The British Museum

The first settlers in northern Sudan date back 300,000 years. It is home to the oldest sub-Saharan African kingdom, the kingdom of Kush (about 2500–1500 BCE). This culture produced some of the most beautiful pottery in the Nile valley, including Kerma beakers.

Sudan was coveted for its rich natural resources particularly gold, ebony and ivory. Several objects in the British Museum collection are made of these materials. Ancient Egyptians were attracted southward seeking these resources during the Old Kingdom (about 2686–2181 BCE), which often led to conflict as Egyptian and Sudanese rulers sought to control trade.

Kush was the most powerful state in the Nile valley around 1700 BCE. Conflict between Egypt and Kush followed, culminating in the conquest of Kush by Thutmose I (1504–1492 BCE). In the west and south, Neolithic cultures remained as both areas were beyond the reach of the Egyptian rulers.

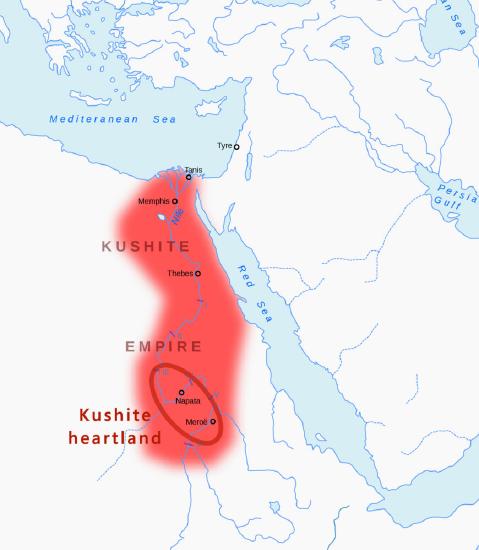

Egypt withdrew in the eleventh century BCE and the Sudanese kings grew powerful. They invaded Egypt and ruled as Pharaohs (about 747–656 BCE). At its greatest, their empire united the Nile valley from Khartoum to the Mediterranean. King Taharqo’s sphinx remains a testament to Kushite power and authority.

The Kushites were expelled from Egypt by the Assyrians, but their kingdom flourished in Sudan for another thousand years. Their monuments and art display a rich combination of Pharaonic, Greco-Roman and indigenous African traditions which may be seen in the chapel relief of Queen Shanakdhakete (Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\)) and aegis of Isis in the Museum collection.

Kerma ware pottery beaker

The cultures of Kerma flourished between about 2500 and 1500 BCE. Their most distinctive products were ceramics. The potters were able to produce incredibly fine vessels by hand, without using a wheel. The pot shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) belongs to the so-called ‘Classic Kerma’ phase, from around 1750 to around 1550 BCE. Classic Kerma pottery is characterized by a black top and a rich red-brown base, separated by an irregular purple-grey band. The black tops and interiors are usually extremely fine and have a distinctive metallic lustrous appearance.

Kerma remained independent during Egypt’s initial forays into Sudan. This situation changed after 1500 BCE, when the Egyptians defeated the Kushites and began to administer the area via their representative, the ‘Viceroy of Kush’, based at Kerma.

Black polished incised ware cup

The handmade pottery produced by C-Group craftsmen is highly distinctive. Although some forms are comparable to Egyptian types of the same period, others are quite different. These show a strong African influence.

This cup (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)) has features characteristic of the African-influenced group known as ‘polished incised ware.’ The cup has a round bottom and is bowl-shaped, though it is small enough to be considered a cup. Vessels of this shape were probably designed to hold food and drink. The African influence is shown most clearly in the cup’s decoration. The exterior is incised with diamonds filled in with cross hatching, perhaps derived from designs used in basket work. Other motifs include herringbone patterns and other geometric shapes of smooth and incised areas.

The incised decoration was applied to the pot before the clay was dry. The vessel was fired to leave a black or sometimes a red finish, which was highly polished. Finally, white pigment was rubbed into the incisions to make the pattern stand out. The remains of the white pigment can be seen in some areas on this cup, but most is now lost.

Sesebi and Egyptian domination

This beautiful vase (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)) was found in a plundered part of the cemetery at Sesebi in southern Nubia. It is an excellent example of the use of faience in a color other than blue. Decoration has been added to the cream body in blue and black, in the form of two friezes of lotus petals at the base and neck, with lotus buds hanging down; the vase itself is in the shape of a lotus bud.

From around 1560 until 1070 BCE, the Egyptians took possession of all Nubian lands as far as the Fourth Cataract of the Nile. The newly won land was divided into two territories: Wawat in the north and Kush in the south. Resources were intensively exploited by the Egyptian empire. Many native inhabitants were recruited into Egyptian armies or employed as laborers on Egyptian civil and religious estates.

New towns and temples were built during the period of Egyptian domination, including Sesebi, founded during Akhenaten’s reign (1352–1336 BCE). Many Nubians embraced the language, religion and forms of aesthetic expression of their overlords. This vase shows strong Egyptian influence in shape and style; to ancient Egyptians the lotus was symbolic of rebirth and new life.

A powerful Kushite dynasty emerges

The Egyptians withdrew from Sudan around 1070 BCE, and by the ninth century a second powerful Kushite dynasty had emerged there. Taking advantage of instability and political disunity in Egypt, the Kushite king Kashta extended his control to Thebes in Egypt by the mid-eighth century B.C.E. His successor Piankhi (Piye) achieved complete control of the Egyptian Nile valley by around 716 BCE. He and his three successors, Shabaqo, Taharqo and Tamwetamani, were acknowledged as the legitimate sovereigns of Egypt, forming the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. Their capital was the important religious centre of Napata, near the Fourth Cataract of the Nile.

Kushite control of Egypt ended when Assyrian forces invaded between 674 and 663 BCE, but Kush remained a major power in Sudan for over a thousand years. After 300 BCE, the Kushite rulers were buried at Meroe in a fertile grassland region northeast of Khartoum. Meroe became the centre of a flourishing economy and developed commercial links with the Mediterranean world. Art and architecture displayed Egyptian influence, but archaeology also points to a growth of local traditions. A strong local element was apparent in religion, with Nubian deities such as the lion-headed Apedemak appearing alongside the Egyptian Amun, Osiris and Isis. The Kushite dynasty ended around 350 CE.

Ornamental head of a goddess, possibly Isis

The term aegis is used in Egyptology to describe a broad collar surmounted by the head of a deity, in this case a goddess, possibly Isis (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Representations in temples show that these objects decorated the sacred boats in which deities were carried in procession during festivals. An aegis was mounted at the prow and another at the stern. The head of the deity identified the occupant of the boat and it is likely that this example came from a sacred boat of Isis.

The eyes and eyebrows of the goddess were originally inlaid. The large eyes, further emphasized by the inlay, are typical of later Kushite art. The rectangular hole in her forehead once held the uraeus, which identified her as a goddess. The surviving part of her head-dress consists of a vulture—the wing feathers can be seen below her ears. The vulture head-dress was originally worn by the goddess Mut, consort of Amun of Thebes, but became common for all goddesses. The rest of the head-dress for this aegis was cast separately and is now lost, but would have consisted of a sun disc and cow’s horns. The piece bears a cartouche of the Kushite ruler Arnekhamani (reigned about 235–218 BCE), the builder of the Lion Temple at Musawwarat es-Sufra.

Burials of Kushite kings

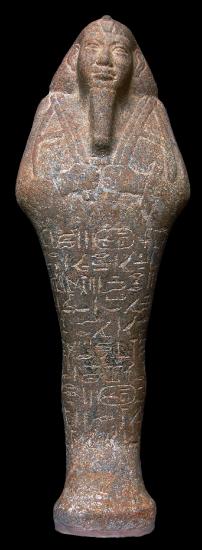

The early Kushite kings were buried on beds placed on stone platforms in the tombs under their pyramids. These structures were based on the pyramids of Egyptian private tombs of the New Kingdom (about 1550–1070 BCE), but the style of burial was entirely Kushite. King Taharqo (690–664 BCE) introduced more Egyptian elements to the burial, such as mummification, coffins and sarcophagi of Egyptian origin, as well as the provision of shabti figures such as the one in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\). These figures were in the style of the Middle and New Kingdoms, the era that the Kushites considered the height of Egyptian culture. The use of stone and the rugged features of these large shabtis are characteristic of early examples.

During period of Kushite control of Egypt, the kings resided mainly at Memphis, and Kushite princesses were appointed to the religious office of ‘God’s Wife of Amun’. The Twenty-fifth Dynasty rulers—Piankhi, Shabaqo, Taharqo and Tamwetamani—brought much-needed stability to Egypt, which had been divided into small areas and governed by local dynasts. Art, architecture and religious learning were revived and Taharqo in particular was an active builder, constructing a number of temples in both Egypt and Nubia. However, it was during Taharqo’s reign that Assyrian invasions forced the Kushites out of Egypt. Control was regained by his successor Tamwetamani (664-656 BCE) but quickly lost again.

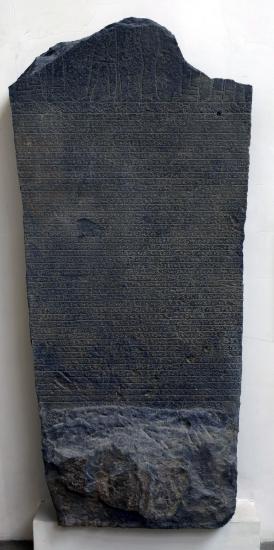

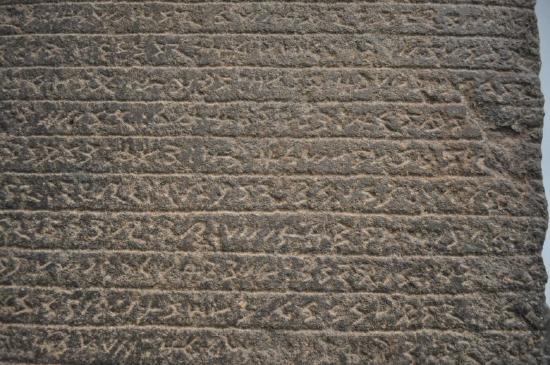

One of the longest known monumental texts in Meroitic

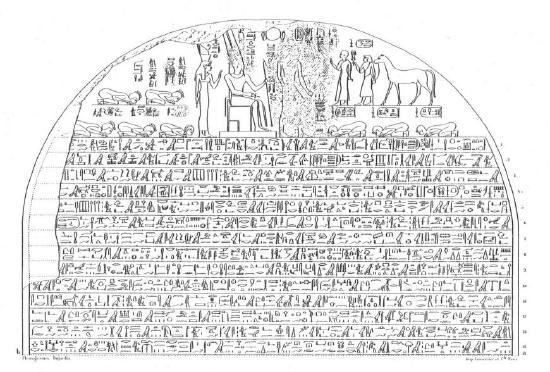

This stele (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)) is one of a pair found at Hamadab a few kilometers south of Meroe in Sudan, the capital of the ancient Kingdom of Kush. They stood either side of the main doorway into a temple.

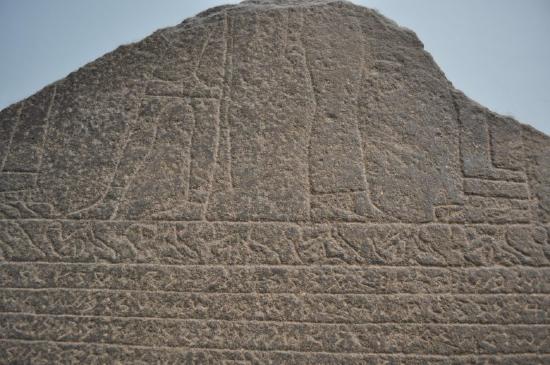

At the top of the stele (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)) are the remains of a relief panel depicting the Kushite rulers Queen Amanirenas and Prince Akinidad. On the left they are shown facing a god, probably Amun, whilst on the right they are facing a goddess, probably Mut. Below this is a frieze depicting bound prisoners.

An inscription in Meroitic cursive script is carved on the lower part of the stele (Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). Meroitic was the indigenous language of the Kingdom of Kush. It is one of the few ancient languages yet to be deciphered. The alphabet consisted of 15 consonants, four vowels and four syllabic characters, but the meaning of the words is not known. In this inscription, the names of Amanirenas and Akinidad are recognizable. It is thought that Amanirenas was the Kushite ruler during the Kushite conflicts against the Romans in the late first century BCE. This inscription may commemorate a Kushite raid on Roman Egypt in 24 BCE.

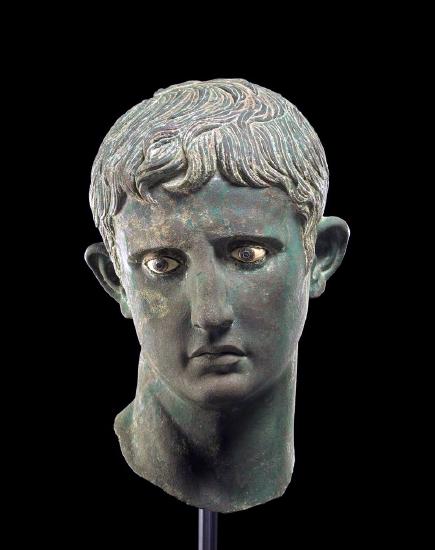

A number of Roman imperial statues were taken during this raid, possibly including a bronze head of Augustus (Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)) which was found in Meroë and is now held in the Museum’s collection.

King Piye and the Kushite control of Egypt

by The British Museum

Who was king Piye?

Piye, also called Piankhy (747–716 BCE) and Kushite ruler of the Napatan period, laid the foundations for the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt (747–656 BCE). He seized control of Upper Egypt within the first decade of his reign, and his sister Amenirdis I was adopted by Shepenwepet I as the next God’s Wife of Amun, thus acquiring Theban territories previously controlled by Osorkon III. In 728 BCE, when Tefnakht, the prince of Sais, created an alliance of Delta rulers to counter the growing Nubian threat, Piye swept northwards and defeated the northern coalition. His successful campaign is described on his victory stela.

In 716 BCE Piye died after a reign of over thirty years. He was buried in an Egyptian style pyramid tomb at El-Kurru (Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)), accompanied by a number of horses, which were greatly prized by the Nubians of the Napatan period. Piye was succeeded by his brother Shabako (716–702 BCE) who re-conquered Egypt and took full pharaonic titles, establishing himself as the ruler of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of all Egypt.

An Egyptian textile that tells of a Kushite king

Vast quantities of linen were used in the daily rituals of Egyptian temples. Some of this linen was donated, often inscribed with the name of the donor. This piece of high quality linen (Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\)) was donated by the Kushite king Piye to a temple of Amun-Re, possibly at Karnak. A column of inscription, close to the fringed edge of the cloth, gives the king’s titles and a year date, presumably the year of king Piye’s reign.

The year date is fragmentary. Two symbols for the number ’10’ survive, indicating that the date must be higher than Year 20. The most likely reading of the group is ‘Year 30’, but ‘Year 40’ has also been proposed. In either case, this is the highest known year of reign for this king.

The relatively good condition of the cloth suggests that it found its way into a tomb. Food offerings in temples were returned to the priests once the gods had magically taken what they wanted. The same was the case for other items used in everyday cult activities. When linen cloths became too old to use, they could be given to priests for their burials, although some might have been given directly to favored officials by the king.

Objects that speak to the Kushite royal family

This hinge (Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\))is of massive proportions, and probably belonged to one of the many monumental doorways of a Theban temple. Although there are extensive remains of the stone parts of these structures, little remains of the door and doorway furniture and fittings, which were often taken down and reused.

The hinge is inscribed with the names of Amenirdis I and Shepenwepet II, both of whom successively held the office of God’s Wife of Amun. Amenirdis was the sister of King Piye, who was the first major ruler in Egypt of the Kushite Dynasty (referred to as the Twenty-fifth Dynasty). He installed his sister in this important religious office in order to maintain control of the southern region of Egypt, administered from Thebes. The holder of the office was celibate, and the successor was adopted by the current holder. Amenirdis adopted Piye’s daughter, her own niece, Shepenwepet II.

The names of the women appear in cartouches because they were considered to be the spouses of the god, and also because they were members of the Kushite royal family. The name of Piye, in the central cartouche, has been deliberately erased. This was probably done during the twenty-sixth dynasty when native Egyptian rule was restored.

King Taharqa introduced more Egyptian elements to burial

Egypt was brought partially under Kushite domination by Piye (reigned about 747–716 BCE). On his commemorative stele he claims that he was acting with the blessing of the god Amun to restore order to the country. At the time, Egypt was politically divided into small areas, governed by local dynasts who often styled themselves as kings.

It was the ambition of Piye and his successors to restore Egypt to greatness. Unfortunately, their intervention in political affairs in Palestine brought Egypt to the attention of the Assyrian empire. King Taharqa (690-664 BCE) eventually lost Egypt to the Assyrians. The country was regained only briefly by his successor Tanutamun (664–656 BCE).

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Meroitic period of the Kingdom of Kush

by The British Museum

Ancient Sudan: The Meroitic Period (about 300 BCE–350 CE)

The Meroitic period, the later phase of rule by the Kushite kings, is named after the royal burial ground at Meroe. In the third century BCE, the royal cemetery was moved there from Napata, though Meroe had long been one of the major centers of the Kushite state. This move broadly coincided with the arrival of Greek culture in Egypt, following the country’s conquest by Alexander the Great. The resulting Greco-Egyptian culture rapidly influenced the Kingdom of Kush giving its later phases a distinctive character. This was in contrast to the preceding Napatan period, which was influenced by the Pharaonic culture. The Kushite kingdom prospered, its rulers and the elite deriving wealth from control of the trade routes along the Nile valley from Central Africa to Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt.

Throughout the Meroitic period Egyptian elements introduced into Kushite royal burial practices under the early Napatan kings were retained and reinterpreted. The sculpture and architecture of the period shows much influence from the Greek and the Greco-Roman world. The fine pottery decorated with geometric forms and floral and animal motifs shows a similar influence. Monumental inscriptions were traditionally written in the hieroglyphic script but, from the second century BCE onwards, the use of the native language of the Kushite Kingdom, Meroitic, became common. Although some words in Meroitic can be translated, its meaning remains largely unknown to us.

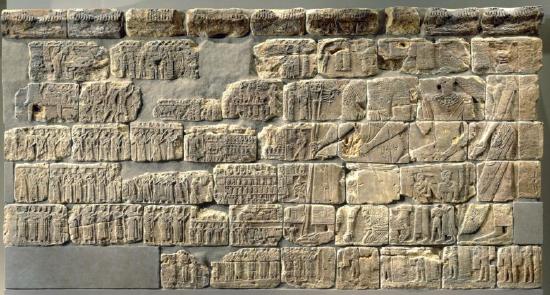

First female ruler of the Meroitic Period

The royal cemetery at Meroe has given the name ‘Meroitic’ to the later stages of rule by the Kushite kings. The Meroitic script has been deciphered, but the language is still not fully understood. This wall (Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\)) comes from one of the small steep-sided pyramids with chapels in which the rulers were buried. It was probably that of Queen Shanakdakhete, the first female ruler. She appears here enthroned with a prince, and protected by a winged Isis. In front of her are rows of offering bearers and also scenes of rituals including the judgement of the queen before Osiris. Although the reliefs are in a style that looks Egyptian, they have their own, independently developed, characteristics.

The term ‘Kush’ or ‘Kushite’ was used long before the eighth century BCE to refer to Nubian ruling powers. But it is particularly used to describe the cultures whose first major contact with Egypt began with the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, and whose Nubian kings put an end to the fragmented state of Egypt by 715 BCE. However, Kushite rule did not last long in Egypt. In the face of Assyrian attack, the last Kushite kings, Taharqa and Tanutamun, fled to Nubia. There they and their descendants were dominant until the fourth century CE, and were buried at el-Kurru, Nuri, Gebel Barkal, and Meroe.

The spirit of a wealthy woman

The Egyptians believed that a person’s essence or soul was composed of several elements. These became separated at death. The ba was one of the elements of the spirit, which encompassed the personality and emotions. It stayed close to the body of the deceased and was eventually reunited with other elements, to live eternally in the Afterlife.

In Egyptian art, the ba is chiefly represented on funerary papyri. These representations were intended to enable the deceased’s entry into the Afterlife. In a funerary context, the ba in its form of a human-headed bird was retained in the Meroitic period. However, the style, the material used, and the location of representations was entirely different from earlier depictions. A stone statue like the one in Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\) would have been placed outside the tomb chapel of a wealthy individual, in this case a woman.

The reduction of the body to its essential details perhaps reflects a continental African influence. This example shows the ba in a female human form, wearing a long dress, but with wings instead of arms. The emphasis on the eyes is typical of later Meroitic sculpture, but the Egyptian origins of the statue can be seen in their almond shape and heavy outline.

Offering tables with Meroitic script

Meroitic offering tables tend to be roughly square in shape, with a central depression for holding liquids. Some examples, such as the one in Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\), bear representations of the food which would be placed on the table, while others have figured decoration. Around the outside is an inscription which names of the owner and gives his parentage.

The Meroitic language is written in two scripts, one derived from hieroglyphs and the other a more cursive form, as here. Although the sound-values of the signs are known, insufficient material for comparison, especially bilingual inscriptions or related languages that are understood, has been found to enable the language to be analyzed or translated properly. Thus names can mostly be read, but the longer inscriptions largely defy interpretation.

Fineware vessels

Meroitic graves often included fragile bowls, jars and cups. The fine quality of the manufacture and decoration of these vessels (Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\)) suggests that they were the prized possessions of the deceased, who wanted to continue to enjoy them in the Afterlife.

Although the vessels themselves were of local manufacture, the designs were often inspired by the artistic traditions of other countries, such as Egypt and the Mediterranean world. Symbols such as the ankh were borrowed from Egypt, as were the lotus and papyrus plants. Although still recognizable, the Meroitic artists interpreted them in their own way, often producing a geometric pattern, which would be unfamiliar to their Egyptian counterparts.

Other motifs, such as animals like frogs, snakes and fantastic beasts, were drawn from the Mediterranean world. The origin of the boat design on this cup is less clear. The tall prow and stern of the vessel, and the stick figure inside is reminiscent of the decoration of Egyptian pots in the Predynastic period, three thousand years earlier. The resemblance ends here though, and is purely coincidental.

A transcultural amphora

Fineware bowls, cups and jars were often placed in Meroitic graves, to be used by the deceased in the Afterlife. Like the fragile fineware vessels, this amphora (Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\)) is covered in a red slip upon which the painted decoration is applied in bands, using a basic palette of black, red and white. A picture of the vessel itself appears on the neck of the amphora.

The decorative motifs are derived from those of Ptolemaic and early Roman Egypt, from about the third to the first century BCE. The combination of geometric, floral and animal motifs is typical of pottery of this period. It shows the influence of the Mediterranean world, which was becoming ever more pronounced as Egypt came under the domination of the Greeks, and then the Romans. The running vine leaves continued to be a popular motif into the Coptic period, appearing on pottery until the Arab conquest in the seventh century CE.

Animal motifs were common in the art of the Mediterranean world. The ducks at the base of this vessel could have been observed from local wildlife. They could also be derived from Egyptian art, in which they were frequently depicted, or copied from hieroglyphic symbols.

Articles in this section:

- The British Museum, "Meroitic period of the Kingdom of Kush," in Smarthistory, March 9, 2021 (© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA)

- The British Museum, "Ancient Nubia and the Kingdom of Kush, an introduction," in Smarthistory, February 24, 2021 (© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA)

- The British Museum, "King Piye and the Kushite control of Egypt," in Smarthistory, March 11, 2021 (© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA)