1.0: Welcome

- Page ID

- 180500

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Welcome

This text is a labor of love, a work in progress, and a team effort—in which you are now an integral part as a reader. We want all of our students to have access to a high-quality textbook, full of accurate information and rich images, comparable to some of the most expensive textbooks, but without the high price tag.

If you are using this text, you are likely taking a course such as “Art History I” or “Survey of Western Art History,” also known as Art History 110 in the C-ID system, which is a collaboration between the California Community Colleges, California State Universities, and Universities of California to help students transfer seamlessly between the three systems of public higher education in California. This textbook stems from a collaboration between California Community College art history faculty, using Open Educational Resources (OERs) written by art historians for such organizations as SmartHistory and Boundless Art History. Other materials, including photographs and videos, come from museums and scholars around the world.

Although our main goal has been to help students succeed by providing a free online or low-cost print textbook, editing this book also gives us the opportunity to correct what we see as a problem in the textbooks used in the introductory art history survey courses that we each took as undergraduates (somewhere between 1972 and 2002). These textbooks (in their current editions) are still the standards today, and belong to a tradition in art history that appears to place Italy in the center of the art world. Lots of great developments happened in Italy, but this is not an accurate or equitable way of presenting the cultures included in a survey of art history from the earliest art through medieval art.

In addition to seeking examples from a broader geographical range and situating cultures in new milieus, we have also included comparisons to distant cultures in order to encourage critical thinking and make global connections.

Survey of Western Art History

As we mentioned above, you are likely using this text for a class called something like “Survey of Western Art History.” Titles and terms like this could use some explaining, so we will take a closer look at each of these three elements, one at a time, below: survey, art history, and Western.

Survey

First of all, the word survey is an indication that the course content is just an overview, barely scratching the surface. Entire books can be written—and often have been!—about the material covered in just one paragraph of a typical survey text. Whole courses are dedicated to material addressed in just one section of a single chapter in this textbook. Our purpose here is not to dig deeply (although we do hope some of you might be inspired to dig deeper and take more art history courses), but rather to provide an overview of art from a huge swath of history and geography.

That necessarily means limiting the cultures, objects, and themes we are able to discuss. We simply cannot cover all art, from all people, cultures, and regions during this huge span of time. Instead, we will focus on highlighting points of cultural contact and resulting artistic influences; different cultural beliefs attached to particular artistic content and production; and varied cultural uses of and investment in object types and media.

In such a large survey, chronology is also an issue to think about. Traditionally, art history surveys are usually taught in chronological order, much as this book is laid out, covering art from the Stone Age to medieval art. Sometimes this is not possible, as major cultures are contemporary to one another, like ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. However, this can be limiting, particularly in thinking of the earliest art and in making global comparisons. Sometimes we will explore art in a less linear fashion in order to encourage critical thinking outside of the confines of chronology.

Art History

You are probably familiar with the meaning of the individual words “art” and “history.” Together, though, they refer to an academic discipline that usually is first offered at the college level. It is the study of objects and structures made by humans, and what those artifacts can teach us about the cultures, beliefs, and stories of the people and groups that made them. Art historians study the people who made these objects, in addition to considering when, how (with what materials or techniques), and why they made them. They also look for patterns across time, place, cultures, and regions to identify and understand particular historical periods.

Art history as a discipline is where it is today because of developments that occurred after the period this course covers.

Some of these foundational events include:

- The birth of art history as a field with the publication of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, written in 1550. As the title implies, Vasari thought of the arts as a contest in which the very best artists would prove their superiority. He ranked Tuscan art as the very best (is it surprising to learn that he was Tuscan?). Remember how we mentioned that Italy appears to be the center of the art world in most traditional art historical texts? Vasari’s book helped make this so, while also launching a long line of Eurocentric art historians. His attitude towards art from other areas is indicated by his labeling German architects as “Goths.”

- Powerful people collected art and often let others see their collections so that they could admire both the art and the owner’s taste. Collectors in Italy had the advantage of living amidst the ruins of the Roman Empire. In this sense, ownership of art was a mark of prestige.

- The establishment of monetary value for art—not just for the materials used—led to the establishment of the art market, centering on the various courts of Europe. Art historians have often prized the Paris art market—first in the courts of the king and nobility, and then in the more open, public market consisting of shops, art academies, and exhibitions.

- As art, and knowledge of art, gained prestige, socially and intellectually ambitious people traveled all over Europe to experience works of art and architecture. Many rich Europeans did not consider a man’s education complete until he took a trip to Europe termed “the Grand Tour.” Women were much less likely to undertake the Tour. From English lords to Russian princes, wealthy “tourists” made months-long journeys that had to include many places in Italy (Florence, Rome, and Naples), as well as Paris, France. There, they often bought art to take home.

- Eventually, many of the private collections that the tourists visited became museums, and rulers established museums which they then filled with the best ancient Roman, Italian, and French art they could access.

These are only some of the factors that reinforced the idea that the best art came from Italy and France, and it lingers in what is called “the art historical canon”—a list of the art that is most worthy of our attention and study. Other distinctions and labels in regards to the type of artistic production also remain tied to the notion of the traditional art historical canon. In this text, we will question and critique the canon, considering the following kinds of questions: What kind of art is included in art history? Why was archaeology traditionally separated from art history and how can we include archaeological and architectural sites in the context of art history now? Why is painting or sculpture often considered “fine art” while a painted ceramic plate or weaving might be termed “craft” or “material culture”? Does the utilitarian purpose of art set limitations on whether it can be considered “art” or “craft”?

Many of these kinds of distinctions were determined by Eurocentric art historians who privileged certain types of artistic production and media over others, often reinforcing false divisions based on who was producing the work rather than the skill of the artists or the aesthetics of the art itself. Have you noticed that a lot of art made by women and artists outside of Europe, such as basketry, textiles, needlepoint, and ceramics, might be termed “craft” while an oil painting or sculpture is considered “fine art”? We want to level the playing field in how we approach and appreciate global artistic production, no matter the medium, artist’s identity, artist’s origin, nor the original use of the art.

Now, thankfully, art historians have expanded the canon beyond what Vasari pioneered. And there is still much work to do! In compiling this textbook, our team has two major goals:

- Maintain all of the cultures that are required for the course.

- Shift the way these cultures are presented to better account for their global context in the world.

As a guiding principle, we seek to present major cultures and artworks in their broader contexts. For example:

- The major commercial textbooks deal with Paleolithic art as if the only remaining traces are found in France and Spain. However, Paleolithic people around the globe made art. As such, we have included Paleolithic art found in South Africa, Namibia, and Algeria as well.

- Alexander the Great’s conquests impacted not just the Greco-Roman world; and so we look at the impact of his conquests on the art of Gandhara, Afghanistan, and Egypt.

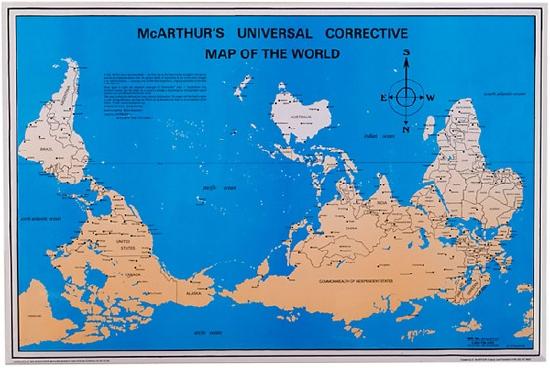

TAKA@P.P.R.S, CC BY-SA 2.0) Why is this map "upside down"?

“Western”

This naturally brings us to tackling that tricky word in the middle of the course title Survey of Western Art History: Western. This word is the most challenging and problematic one. It is both relative (west of where?) and subjective (who determines what fits that label?). Traditionally, “Survey of Western Art History” classes have included art from Western Europe; the so-called “Near East” (Mesopotamia, Syria, Israel, etc.—which is given this name to distinguish it from the next general region); the so-called “Far East” (China, Korea, Japan, etc.); North America (excluding Native American art); and Egypt (but not the rest of Africa).

In other words, even though you might assume from the label that it has something to do with geography, it does not. “Western” here does not mean art from the western hemisphere (i.e., the Americas). It means the opposite of East, indicating an understanding of the world in which Europe, and later, some of its colonies, is the West; all of Asia is the East; and Africa and the Americas, with the exception of the U.S. and Canada, are the South. It is a particularly Eurocentric way of separating the world. The art historical tradition we have inherited was largely shaped by white, European, men, and that is a model that still persists.

Egypt, which is in Africa, and Mesopotamia, which is in Asia, are included in “Western” art history because of their importance to the traditions of Western Europe. Considering the list of cultures required in Art History 110, it would be easy to conclude that since the rise of the Roman Empire, the West has consisted basically of only Italy and France. We hope to help you see the flaws in this line of thinking, by highlighting broader global connections and problematizing such a relative and Eurocentric term as “Western”—all while still teaching this very “Western” survey! McArthur's Universal Corrective Map of the World, shown above, in which north is shown toward the bottom of the page and south toward the top, helps illustrate just how arbitrary—and pervasive—a "Western" framing can be.

This textbook

Because of all of the terms and problems cited above, our survey text is a little bit different. In addition to being free and online, its intent is more inclusive. It is still only scratching the surface, and we will still include those traditionally-covered regions and objects, from the Paleolithic through the Gothic periods, but we are trying to give a broader, more accurate perspective of the ways techniques, objects, and ideas traveled and influenced each other.

Art history has inherited a lot of traditions, some of which we will continue to point out, question, and critique as we go. Our goal is to help you gain a broad understanding of this material, while also equipping you to think carefully and critically about what you read and see—not just in this textbook, but in the rest of your college career and post-college life.

With this book, we aim to:

- Equip you with a high quality, accessible textbook that challenges all of us to think outside of the standard art historical text

- Encourage and nurture critical thinking, questioning, and expansive thinking about the function and relevance of artifacts and artistic production

- Acknowledge and explore the historiography of art history (the writing of art history or the study of art historical writing), with the hopes of offering you the tools needed to think critically about how we got where we are in the field and how to approach the discipline moving forward

- Make choices that move outside the notion of a fully representational, static, and one-dimensional art historical canon, by embracing other ideas on how to engage with or evaluate the relevance and resonance of an art object

- Reframe and encourage questioning of traditional art historical narratives not only by acknowledging their flaws, but also by embracing alternative narratives that illustrate a broader, more accurate and inclusive story of art history

Keeping your eyes open is what art history is all about. We hope that by the time you complete your course, you will be able to tell Paleolithic from Neolithic, Romanesque from Gothic, and lots more in between, but what we really want for you is to be a great thinker and observer—to take the time to look carefully at a work of art, to identify its formal elements, and to think about the context of its creation.

We live in a highly visual society; low estimates suggest that the average person sees about 5,000 advertisements a day! We hope to encourage you to approach all of the imagery you see in your life in a thoughtful and inquisitive manner, taking your newly cultivated skills in critical thinking and analysis into the rest of your life.

The world is a huge, strange, wonderful, and endlessly fascinating place. As we travel through the art world with this text, we hope that you will find yourself inspired to travel and experience art, physically and virtually as well.

Welcome again, readers; we are glad to have you here.

—Cerise Myers, Textbook Project Lead and Assistant Professor of Art History at Imperial Valley College, PhD in Contemporary Art History

—Ellen C. Caldwell, Assistant Project Lead and Professor of Art History at Mt. San Antonio College, MA in Contemporary West African Art History

—Margaret Phelps, Adjunct Professor of Art History at Ventura County Community College District, MA in the History of Photography

—Lisa Soccio, Professor of Art History at College of the Desert, PhD in Visual and Cultural Studies

—Alice J. Taylor, Professor Emerita of Humanities at West Los Angeles College, PhD in Late Antique and Byzantine Art History