30.2: The Art World Grows

- Page ID

- 53141

Assemblage

Assemblage is the practice of creating two-dimensional or three-dimensional artistic compositions by combining and manipulating found objects.

Learning Objectives

Describe the origins and growth of assemblage art.

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Though the term was not in use until the 1950s, assemblage originates with early 20th century avant garde movements that sought to challenge traditional artistic media.

- One of the most significant assemblage artists, active beginning in the 1930s and 40s, was Louise Nevelson, whose wooden wall-like sculptures disguised their found-object components under spray paint.

- In the 1960s, neo-Dadaist Robert Rauschenberg became notable for his “combines.” These pieces served to break the boundaries between art, sculpture, and the everyday so that all were present in a single work of art.

Key Terms

- found-object: A natural object, or one manufactured for some other purpose, considered as part of a work of art.

Assemblage is an artistic process whereby two- or three-dimensional artistic compositions are created by combining found objects. While similar to the process of collage, it is distinct in its deliberate inclusion of non-art materials.

The origin of the term in its artistic sense can be traced back to the early 1950s, when French artist Jean Dubuffet created a series of collages of butterfly wings titled “assemblages d’empreintes.” However, the origin of the artistic practice dates to the early 20th century, as both Marcel Duchamp and Pablo Picasso as well as others worked with found objects for many years prior to Dubuffet. Russian constructivist artist Vladimir Tatlin created his “counter- reliefs ” in the middle of 1910s. Alongside Tatlin, the earliest woman artist to try her hand at assemblage was Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, the Dada Baroness. The most recognizable assemblage pieces from this period are the readymades of Marcel Duchamp, such as Fountain, 1917. Readymades were found objects that Duchamp chose and presented as art. The idea was to question the notion of art and the accepted canon, as well as the adoration of art, which Duchamp found “unnecessary. ”

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain: Duchamp’s appropriation of a urinal as a piece of art challenged the prevailing definition of sculpture.

Another early and prolific assemblage artist was Louise Nevelson, who began creating her sculptures from found pieces of wood in the late 1930s. Nevelson’s most notable sculptures are wooden, wall-like, collage-driven reliefs consisting of multiple boxes and compartments that hold abstract shapes and found objects from chair legs to balusters. Nevelson described these immersive sculptures as “environments.” The wooden pieces were cast-off scraps found in the streets of New York. Unlike Duchamp’s poor attempt to mask the urinal’s true form, Nevelson spray painted found objects to disguise them of their actual use or meaning. Nevelson called herself “the original recycler” because of her extensive use of discarded objects, and credited Pablo Picasso for the cube that served as the groundwork for her cubist-style sculpture.

In 1961, the exhibition “The Art of Assemblage” was featured at the New York Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition showcased the work of early 20th century European artists such as Braque, Dubuffet, Marcel Duchamp, Picasso, and Kurt Schwitters alongside Americans Man Ray, Joseph Cornell, Robert Mallary, and Robert Rauschenberg. It also included lesser-known American West Coast assemblage artists such as George Herms, Bruce Conner, and Edward Kienholz. William C. Seitz, the curator of the exhibition, described assemblages as preformed natural or manufactured materials, objects, or fragments not originally intended as art.

Robert Rauschenberg is a significant proponent of assemblage art. Rauschenberg picked up trash and found objects that interested him on the streets of New York City and brought these back to his studio where they could become integrated into his work. These works, which he called “combines,” served as instances in which the delineated boundaries between art, sculpture, and the everyday were broken down so that all were present in a single work of art. Technically “combines” refers to Rauschenberg’s work from 1954 to 1962, but the impetus to combine both painting materials and everyday objects such as clothing, urban debris, and taxidermic animals continued throughout his artistic life.

Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon: This assemblage combines the materials of oil, housepaint, pencil, paper, fabric, metal, buttons, nails, cardboard, printed paper, photographs, wood, paint tubes, mirror string, pillow, and bald eagle on canvas.

Performance Art

Performance art is a genre which presents live art with a conceptual basis.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the diverse manifestations and goals of performance art

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Though Western performance art began with early 20th century avant-garde movements, it flourished during the 1960s and 70s when minimalism and abstract expressionism fell out of favor.

- Performance art often seeks to blur the line between art and life, with 1960s enthusiasm for this medium also reflecting the period’s frustrations with traditional fine art.

- Because performance art shifts between venues, audiences, and styles, it is unattached to established traditions, thriving during sociopolitical unrest and provoking free thought.

Key Terms

- Conceptual art: A genre of art in which the transmission of ideas is more important than the creation of an art object.

- Dada: A cultural movement that began in Zürich, Switzerland during World War I and peaked from 1916 to 1920. The movement primarily involved visual arts, poetry, theatre, and graphic design, and was characterized by nihilism, deliberate irrationality, disillusionment, cynicism, chance, randomness, and the rejection of the prevailing standards in art.

Performance art is a genre that presents live art, usually referring to conceptual art that conveys content through dramatic interaction rather than traditional performances solely for entertainment.

Origins

Western cultural theorists trace performance art to early 20th century avant-garde movements such as Russian Constructivism, Futurism and Dada. The Dada movement led the way with its unconventional poetry performances, often at the Cabaret Voltaire, by the likes of Richard Huelsenbeck and Tristan Tzara. However, the most significant wave of performance art occurred in the 1960s and 70s when abstract expressionism and minimalism became less popular. The enthusiasm for live and innovative performance reflected this period’s interest in moving past preconceptions that limited what could qualify as fine art.

Styles

Performance art was one of many disparate trends that developed as abstract expressionism and minimalism faded. Its breadth and widespread usage, along with each performance existing as a unique occurrence, makes it difficult to summarize performance art’s characteristics. Performance art in the 1960s and 70s included “actions,” body art, happenings, endurance-focused, and ritual -focused performances. “Cut Piece,” an action performed by Yoko Ono in several venues, demonstrates the genre. Ono walked onstage and then knelt on the floor while audience members were encouraged to come onstage and cut off all of her clothing.

Happenings, a term coined by Allan Kaprow in 1958, are unique, improvisational events that can take place in any venue and require participation from spectators. There is no structured beginning, middle, or end, and no hierarchy or distinction between the artist and the viewers. The viewers’ reactions decide the art piece, making each happening a unique experience that cannot be replicated. Through happenings, the separations between life, art, artist, and audience become blurred.

Argentine artist Marta Minujín in a 1965 happening: Reading the News, a happening in which the artist got into the Río de La Plata wrapped in newspapers.

The early works of Marina Abramović exemplify endurance-focused, ritual-based performances that explored issues of human determination, patience and bodily limits. In her first performance, Rhythm 10 (1973), Abramović explored ritual and gesture. Using twenty knives and two tape recorders, she played a Russian game in which she aimed rhythmic knife jabs between her splayed fingers. With this piece and as a performer, Abramović was exploring states of consciousness. Each time she cut herself, she picked up a new knife, began again, and recorded her results. After cutting herself twenty times, she replayed the tape, listening to the sounds she had made and repeating her previous movements. By replicating her mistakes, she was merging her past actions with the present moment. She explored her physical and mental limits by injuring herself, and then honored what she had done by repeating the gestures, encouraging the audience to think about what her ritual symbolized and what it meant to repeat the gestures after her ritual had already been performed.

Performance art seeks to demystify fine art by blurring the line between art and life. Because it can shift fluidly between venues, audiences, and styles and is unattached to traditional forms, performance art thrives in times of social upheaval and political unrest, providing a public forum for discussion, experimentation, and outrage. In the 1980s, performance art fell from favor following renewed interest in painting, but was resurrected in the 1990s in response to issues involving race, immigration, gay rights, and AIDS. Since then, performance art has become increasingly accepted in mainstream culture, shown in art museums and becoming a topic for scholarly research.

Marina Abramović, The Artist is Present, MOMA, 2010: The Artist Is Present is a 736-hour and 30-minute static, silent piece in which Abramovic sits immobile while spectators are invited to take turns sitting opposite her, for as long as they want, while she maintains focused eye contact with them.

Photography in the Latter 20th Century

In the early 20th century, photography evolved through multiple styles as it became accepted as a legitimate fine art medium.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the progression of photography from pictorialism and straight photography to the snapshot aesthetic and conceptual work

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The earliest fine art photography imitated painting styles, often using soft focus for a dreamy, romantic look known as pictorialism.

- In reaction to pictorialism, some fine art photographers advocated for “straight photography,” giving the sharply focused photograph the status of art in its own right.

- Following the World Wars, artistic tastes changed and led to the harsher, cleaner aesthetics of modern art and more interest in urban subject matter.

- Genre photography persisted and the 1960s saw the development of the “snapshot aesthetic,” featuring banal everyday subject matter and off-centered framing.

- Conceptual photography developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s. While these artists utilize photography to illustrate an idea, they often do not consider themselves photographers but rather use photography as a means to document performances, ephemeral sculpture, or actions.

Key Terms

- Conceptual art: A genre of art in which the transmission of ideas is more important than the creation of an art object.

During the 20th century, both fine art photography and documentary photography became accepted by the English-speaking art world and the gallery system. In the United States, pioneer photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, John Szarkowski, F. Holland Day, and Edward Weston spent their lives advocating for photography as a fine art. A culminating moment for pictorialism and for photography in general occurred in 1910, when the Albright Gallery in Buffalo bought 15 photographs from Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery. This was the first time photography was officially recognized as an art form worthy of a museum collection.

Pictorialism

At first, fine art photographers tried to imitate painting styles, giving rise to pictorialism, a style that uses soft focus to create a dreamy, romantic look. Pictorialism dominated photography from about 1885 to 1915, though it was still promoted by some as late as the 1940s. In general, this term refers to a style in which the photographer has somehow manipulated what would otherwise be a straightforward photograph as a means of “creating” an image rather than simply recording it. Typically, a pictorial photograph lacks sharp focus, is printed in one or more colors rather than black-and-white (ranging from warm brown to deep blue), and may have visible brush strokes or other surface manipulation. For the pictorialist, a photograph, like a painting, was a way of projecting emotional intent into the viewer ‘s imagination.

George Seeley, The Black Bowl: George Seeley, The Black Bowl, c. 1907. Published in Camera Work, No. 20, 1907, is a good example of a Pictorialist photograph due to its soft focus and painterly aesthetic.

As the harsh realities of World War I began to spread around the world, the public’s taste for the art of the past began to change. Pictorialism gradually declined in popularity after 1920, fading out of popularity completely by the end of World War II. Weston, Ansel Adams, and others later began to move away from pictorialism and created the Group f/64, which advocated for ‘straight photography’, or, the literal representation of a subject rather than an imitation of something else. During this period, the new style of photographic modernism came into vogue, and the public’s interest shifted to more sharply focused images. As developed countries turned their focus to industrialism and growth, art reflected this change by featuring hard-edged images of new buildings, airplanes, and industrial landscapes. Until the late 1970s several genres predominated, including nudes, portraits, and natural landscapes (exemplified by Ansel Adams).

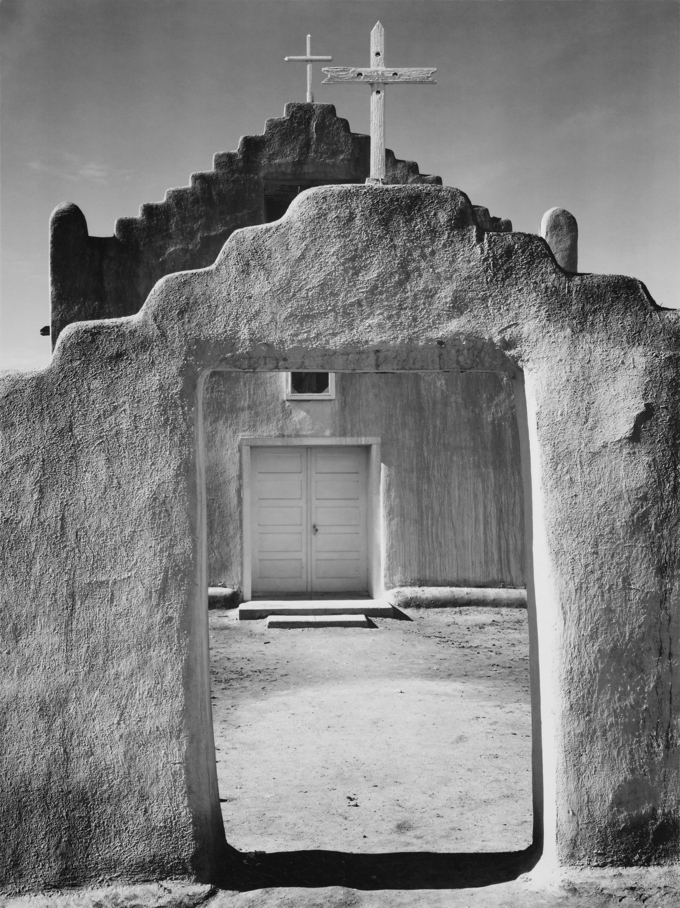

Ansel Adams, Church, Taos Pueblo: Ansel Adams, Church, Taos Pueblo National Historic Landmark, New Mexico, 1942. From the series Ansel Adams Photographs of National Parks and Monuments, compiled 1941-42, documenting the period ca. 1933-42.

Snapshot Aesthetic

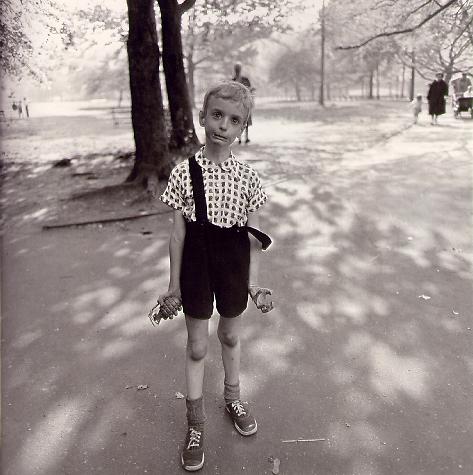

Around 1963, the term “snapshot aesthetic” entered the vocabulary of the fine art photography world. John Szarkowski, who was head of the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art from 1962 to 1991, became one of the trend’s largest promoters, and it became especially fashionable from the late 1970s until the mid 1980s. The snapshot aesthetic typically features off-centered framing and everyday subject matter often presented without apparent link from image-to-image, relying instead on the juxtaposition and disjunction of individual photographs. Notable practitioners include Garry Winogrand, Nan Goldin, Wolfgang Tillmans, Martin Parr, William Eggleston, Diane Arbus, and Terry Richardson. These photographers aimed not “to reform life but to know it” (John Szarkowski, Diane Arbus).

Diane Arbus, Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, 1962: Diane Arbus exemplifies the “snapshot aesthetic” in her work which presents images from the everyday.

Conceptual Photography

Cindy Sherman, Chromogenic Color Print, 1981: Cindy Sherman used a type of performance in her work by photographing herself dressed in costume, expanding the possibilities of the medium.

Conceptual photography is a type of photography that illustrates an idea. While illustrative photographs have been made since the medium ‘s invention, the term conceptual photography derives from conceptual art, a movement of the late 1960s. Today the term describes either a methodology or a genre. Conceptual art of the late 1960s and early 1970s often involved photography that documented performances, ephemeral sculpture, or actions. The artists did not describe themselves as photographers. Since the 1970s, artists like Cindy Sherman, Thomas Ruff, and Thomas Demand have been described as conceptual. Although their work does not generally resemble the lo-fi aesthetic of 1960s conceptual art, they have certain methods in common such as documenting performance (Sherman), typological or serial imagery (Ruff), or the restaging of events (Demand).

Contemporary photography has seen a trend of carefully staging and lighting a picture rather than hoping to “discover” it ready-made. Photographers such as Gregory Crewdson and Jeff Wall are noted for the quality of their staged pictures. Additionally, new technological trends in digital photography have created the possibility of full-spectrum photography, where careful filtering choices across the ultraviolet, visible, and infrared lead to new artistic visions.

Pop Art

The pop art movement began in the 1960s and questioned the boundaries between “high” and “low” art.

Learning Objectives

Identify examples of American pop art

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Pop art presented a challenge to traditions of fine art by including aspects of mass culture, such as advertising, comic books, and mundane, cultural objects in its work. One of the goals of pop art was to blur and question the boundaries between “high” art and “low” art.

- Neo-Dada was one minor artistic movement that contributed to the formation of pop art. In reaction to abstract expressionism, neo-Dadaists sought to create meaning solely through the use of conventional symbols and icons such as targets, flags, letters, and numbers.

- The works of Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol exemplify pop art’s direct attachment to commonplace images in American popular culture, while treating the subject matter in a cool, impersonal manner. This detached style illustrated the idealization of mass production and its inherent anonymity.

Key Terms

- Ben-Day dots: The Ben-Day dots printing process, named after illustrator and printer Benjamin Henry Day, Jr., is similar to pointillism. Depending on the effect, colors, and optical illusion needed, small colored dots are closely spaced, widely spaced, or overlapping. Pulp comic books of the 1950s and 1960s used Ben-Day dots in the four process colors (cyan, magenta, yellow, and black) to inexpensively create shading and secondary colors such as green, purple, orange, and flesh tones.

- mass: A large quantity; a sum.

- abstract expressionism: An American genre of modern art that used improvised techniques to generate highly abstract forms

- silk-screen printing: A method of reproducing colored artwork using a cut stencil attached to a stretched, fine-meshed silk screen.

Although it originated in Britain in the late 1950s, pop art did not gain momentum in America until a full decade later. By this time, American advertising had adopted many elements and inflections of modern art and functioned at a sophisticated level. Consequently, American artists had to search deeper for dramatic styles that would distance fine art from well-designed and clever commercial materials. Pop art presented a challenge to traditions of fine art by including aspects of mass culture, such as advertising, comic books, and mundane, cultural objects. One of the goals of Pop Art was to blur and draw into question the boundaries between “high” and “low” art.

Neo-Dada

Two important painters in the establishment of America’s pop art vocabulary were the American neo-Dadaists Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. In the mid-1950s, Jasper Johns began to appropriate popular abstract iconography for painting, allowing a set of familiar associations to answer the need for a subject. In contrast to the abstract expressionists, who not only disdained subject matter but also took their paintings to be an index of the artist’s presence on the canvas, Neo-Dadaists sought to create meaning solely through the use of conventional symbols and icons such as targets, flags, letters, and numbers. These neutral subjects rejected a reliance on the hand of the artist in the production of meaning–the surface of the painting could declare itself without reference to the persona that created it.

Robert Rauschenberg also was considered a Neo-Dadaist, and his “combines” incorporated found objects, printed materials, and urban debris with traditional fine art materials. Combines served to break down the delineated boundaries between art, sculpture, and the everyday object so that all were recontextualized in a single work of art.

Jasper Johns, Flag, 1954-55, Encaustic, oil, collage on fabric mounted on plywood, 42 x 61 in. Museum of Modern Art, New York.: Flag by Jasper Johns presents the American flag as subject matter, thus invoking a plethora of associations and juxtapositions between the popular image, symbol, and fine art.

Roy Lichtenstein

Of equal importance to American pop art is Roy Lichtenstein. His work defines the basic premise of pop art better than any other through parody. Selecting the old-fashioned comic strip as subject matter, Lichtenstein produced hard-edged, precise compositions that documented mass culture while simultaneously creating soft parodies. Lichtenstein used oil and Magna paint in his best known works, such as Drowning Girl (1963), which was appropriated from the lead story in DC Comics’ Secret Hearts #83. His characteristic style featured thick outlines, bold colors and Ben-Day dots to represent certain colors, as if created by photographic reproduction. Lichtenstein’s contribution to Pop Art merged popular and mass culture with the techniques of fine art while injecting humor, irony, and recognizable imagery and content into the final product. The paintings of Lichtenstein, like the works of many other pop artists, shared a direct attachment to the commonplace image of American popular culture while treating the subject matter in a cool, impersonal manner. This detached style illustrated the idealization of mass production and its inherent anonymity.

Roy Lichtenstein, Drowning Girl, 1963, MOMA: Lichtenstein calls into question notions of appropriation while simultaneously blurring the lines between high and low art in this painting of a scene from a popular comic book.

Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol is probably the most famous figure in pop art. Warhol attempted to take pop beyond art to become a lifestyle, and his work often displays a lack of human affectation that dispenses with the irony and parody of many of his peers. Warhol’s artwork uses many forms of media including and drawing, painting, printmaking, photography, silk screening, sculpture, film, and music. His studio, The Factory, was a famous gathering place that brought together distinguished intellectuals, drag queens, playwrights, bohemian street people, Hollywood celebrities, and wealthy patrons. New York’s Museum of Modern Art hosted a Symposium on Pop Art in December 1962, during which artists like Warhol were attacked for “capitulating” to consumerism. Critics were scandalized by Warhol’s open embrace of market culture. This symposium set the tone for Warhol’s reception.

Throughout the decade it became increasingly clear that there had been a profound change in the culture of the art world, and that Warhol was at the center of that shift. In the early 60s, Warhol pared his image vocabulary down to the icon itself–brand names, celebrities, dollar signs–and removed all traces of the artist’s hand in the production of his work. Eventually, he moved from hand painting to silk-screen printing, removing the handmade element altogether. The element of detachment reached such an extent at the height of Warhol’s fame that he had several assistants producing his silk-screen multiples.

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962, synthetic polymer on 32 canvases. 20 x 16 in each. Museum of Modern Art, New York.: Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans have become synonymous with the pop art movement and exemplify his preoccupation with notions of pop culture and capitalism.

The legacy of Pop Art is expansive, and much of the Pop art of the 1960s is considered incongruent as many different conceptual practices fed into the movement and are reflected by a wide variety of artists. The list of notable Pop artists is extensive, but some major proponents include Jim Dine, Richard Hamilton, Keith Haring, David Hockney, Alex Katz, Yayoi Kusama, John McHale, Claes Oldenburg, Julia Opie, Eduardo Paolozzi, Sigmar Polke, Ed Ruscha, George Segal, and Tom Wesselman.

Photorealism

Photorealism or super-realism is a genre of art that began in the late 1960s, encompassing painting, drawing, and other graphic media in which an artist studies a photograph and then attempts to reproduce the image as realistically as possible.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate photorealism within the era’s contemporary art movements

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Pop art and photorealism were both reactionary movements stemming from the ever-increasing and overwhelming abundance of photographic media, which by the mid 20th century had become such a massive phenomenon that it was threatening to lessen the value of imagery in art.

- Photorealism uses photographs transferred to canvas in paint with tight and precise composition.

- Super-realist painters chose difficult subject matter that emphasized the technical prowess and virtuosity required to simulate, such as reflective surfaces or embellished environments.

Key Terms

- abstract expressionism: An American genre of modern art that used improvised techniques to generate highly abstract forms.

- Pop art: An art movement of the 1950s that presented a challenge to traditions of fine art by including imagery from popular culture such as advertising and news.

Photorealism, also known as super-realism or hyper-realism, is a genre of art that makes use of photography to create a highly realistic art work in another medium. The term was first applied in America during the late 1960s. Like pop art, photorealism was a reactionary movement that stemmed from the overwhelming abundance of photographic media, which by the mid 20th century had grown into such a massive phenomenon that it threatened to lessen the value of imagery in art. While pop artists were primarily pointing out the absurdity of the imagery that dominated mass culture—such as advertising, comic books, and mass-produced cultural objects—photorealists aimed to reclaim and exalt the value of the image.

Process

Photorealist painters gather imagery and visual information through photographs, which are transferred onto canvas either by slide projection or the traditional grid. The resulting images are often direct copies of the photograph, usually on an increased scale. Stylistically, this results in painted compositions that are tight and precise, often with an emphasis on imagery that requires a high level of technical prowess and virtuosity to simulate; for example, reflections in surfaces and embellished, man-made environments.

Ralph Goings, Ralph’s Diner, 1981-82, oil on canvas.: This painting by Ralph Goings displays the artists technical prowess in the realistic depiction of many reflective, textured surfaces.

Richard Estes, Telephone Booths, 1968, oil on canvas: Richard Estes reproduces in a paint the complex image of a reflected urban environment on a telephone booth.

The first generation of American photorealists included such painters as Richard Estes, Ralph Goings, Chuck Close, Charles Bell, Audrey Flack, Don Eddy, Robert Bechte, and Tom Blackwell.

Chuck Close, Mark (1978–1979), acrylic on canvas, left; detail of eye, right: Chuck Close is known for his intensely detailed paintings which are essentially indistinguishable from photographic images.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike