27.1: Religious Art in Africa

- Page ID

- 53114

African Art and the Spirit World

Beliefs about the spirit world are deeply embedded in traditional African culture, but were heavily influenced by Christianity and Islam.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the role of African masks, statues, and sculptures in relation to the spirit world

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Most traditional African cultures include beliefs about the spirit world, which is widely represented through both traditional and modern art such as masks, statues, and sculptures.

- Wooden masks are often used to depict deities or ancestors; in many traditions, they are believed to channel spirits when worn by ceremonial dancers.

- Statues and sculptures are also used to represent, connect to, or communicate with spiritual forces.

- Today, Africans profess a wide variety of religious beliefs, the most common of which are Christianity and Islam; perhaps less than 15% still follow traditional African religions.

- Despite the drastic decrease in native African religions, some modern art in Africa has worked to reincorporate traditional spiritual beliefs, such as in modern Makonde Art depicting spirits.

Key Terms

- receptacle: A container.

- sanctuaries: Consecrated (or sacred) areas of a church or temple.

Background

Like all human cultures, African folklore and religion is diverse and varied. Culture and spirituality share space and are deeply intertwined in most African cultures, which have been heavily influenced by the introduction of Christianity and Islam during the era of European colonization. Most traditional African cultures include beliefs about the spirit world, which is widely represented through both traditional and modern art such as masks, statues, and sculptures. In some societies, artistic talents were themselves seen as ways to please higher spirits.

Traditional Influences on Contemporary Religious Art

Masks and Rituals

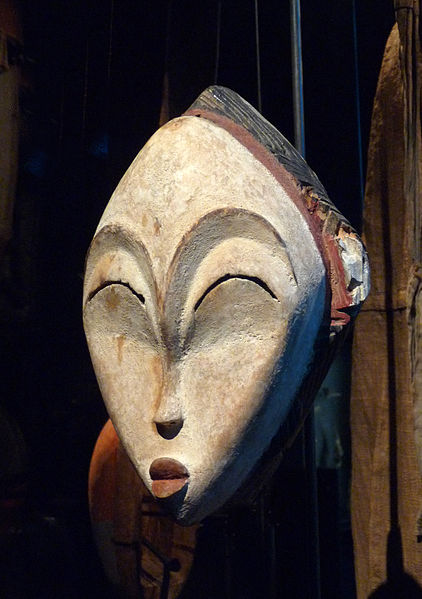

Wooden masks, which often take the form of animals, humans, or mythical creatures, are one of the most commonly found forms of traditional art in western Africa. These masks are often used to depict deities or represent the souls of the departed. They may be worn by a dancer in ceremonies for celebrations, deaths, initiations, or crop harvesting. In many traditional mask ceremonies, the dancer goes into deep trance, and during this state of mind he or she is believed to communicate with ancestors in the spirit world. The masks themselves often represent an ancestral spirit, which is believed to possess the wearer of the mask. Most African masks are made with wood and can also be decorated with ivory, animal hair, plant fibers, pigments, stones, and semi-precious gems.

Mask from Gabon: A traditional mask from Gabon.

Statues and sculptures are also used to represent or connect to spiritual forces. For example, Bambara statuettes, such as the Chiwara, are used as spiritually charged objects during ritual. During the annual ceremonies of the Guan society, a group of up to seven figures, some dating back to the 14th century, are removed from their sanctuaries by the elder members of the society. The wooden sculptures, which represent a highly stylized animal or human figure, are washed, re-oiled and offered sacrifices. The Kono and Komo societies use similar statues to serve as receptacles for spiritual forces. The Igbo would traditionally make clay altars and shrines of their deities, usually featuring various figures. In the Kingdom of Kongo, nkisi were objects believed to be inhabited by spirits. Often carved in the shape of animals or humans, these “power objects” were believed to help aid in the communication with the spirit world.

Modern Religion

Today, the countries of Africa contain a wide variety of religious beliefs, and statistics on religious affiliation are difficult to come by. Christianity and Islam make up the largest religions in contemporary Africa, and some sources say that less than 15% still follow traditional African religions. Despite the drastic decrease in native African religions, some modern art in Africa has worked to reincorporate traditional spiritual beliefs. For example, modern Makonde Art has turned to abstract figures in which spirits, or Shetani, play an important role.

Modern Makonde carving in ebony: Modern Makonde sculptures often depict spirits, or Shetani.

Masks in the Kalabari Kingdom

Culture and artistic festivities of the Kalabari Kingdom involve the wearing of elaborate outfits and carved masks to celebrate the spirits.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the role of the spiritual in the masks of the Kalabari Kingdom

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Kalabari Kingdom was an independent trading state of the Kalabari people, an Ijaw ethnic group, in the Niger River Delta. Today it is recognized as a traditional state in what is now Rivers State, Nigeria.

- Although the Ijaw are now primarily Christians, they also maintain elaborate traditional religious practices.

- Veneration of ancestors plays a central role in Ijaw traditional religion, while water spirits figure prominently in the Ijaw pantheon. In addition, the Ijaw practice a form of divination in which recently deceased individuals are interrogated on the causes of their death.

- The role of prayer in the traditional Ijaw system of belief is to maintain the living in the good graces of the water spirits among whom they dwelt before being born into this world.

- Each year, the Ijaw hold celebrations involving masquerades that last for several days in honor of the spirits.

- Ijaw men wearing elaborate outfits and carved masks dance to the beat of drums and manifest the influence of the water spirits through the quality and intensity of their dancing.

Key Terms

- enculturation: The process by which an individual adopts the behavior patterns of the culture in which he or she is immersed.

- kin: Race; family; breed; kind.

Introduction: The Kalabari

The Kalabari Kingdom, also called Elem Kalabari (New Shipping Port), or New Calabar by the Europeans, was an independent trading state of the Kalabari people, an Ijaw ethnic group, in the Niger River Delta. Today it is recognized as a traditional state in what is now Rivers State, Nigeria. As well as participating in trade, the Ijaw have traditionally been a fishing and farming culture.

Culture and Art

Although the Ijaw are now primarily Christians (95% profess to be), with Roman Catholicism and Anglicanism being the varieties of Christianity most prevalent among them, they also maintain elaborate traditional religious practices. Veneration of ancestors plays a central role in Ijaw traditional religion, while water spirits, known as Owuamapu, figure prominently in the Ijaw pantheon. In addition, the Ijaw practice a form of divination called Igbadai, in which recently deceased individuals are interrogated on the causes of their death. The Ijaw are also known to practice ritual acculturation, whereby an individual from a different and unrelated group undergoes rites to become Ijaw.

The Role of Ijaw Masks

Ijaw religious beliefs hold that water spirits are like humans, having personal strengths and shortcomings, and that humans dwell among the water spirits before being born. Each year, the Ijaw hold celebrations lasting for several days in honor of the spirits. Central to the festivities is the role of masquerades, in which men wearing elaborate outfits and carved masks dance to the beat of drums and manifest the influence of the water spirits through the quality and intensity of their dancing. Particularly spectacular masqueraders are believed to be possessed by the particular spirits on whose behalf they are dancing.

ljaw mask: Mask, Kalabari Ijo peoples, Nigeria, early 20th century, wood, pigment (National Museum of African Art).

Dogon Sculpture

Dogon sculpture primarily revolves around the themes of religious values, ideals, and freedoms.

Learning Objectives

Describe the characteristics of Dogon art, sculpture, and rituals, as well as the background and location of the Dogon culture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Dogon are an ethnic group living in the central plateau region of the country of Mali, in the West of the African continent, and are well known for their unique sculptures. Dogon sculptures are not made to be seen publicly and are commonly hidden from the public eye within the houses of families, sanctuaries, or the hogon (spiritual leader).

- Dogon sculptures are typically characterized by an elongation of form and a mix of geometric and figurative images.

- The Dogon style has evolved into a kind of cubism: ovoid head, squared shoulders, tapered extremities, pointed breasts, forearms and thighs on a parallel plane, and hair stylized by three or four incised lines.

Key Terms

- vessel: A general term for all kinds of craft designed for transportation on water, such as ships or boats.

- Tellem: The people who inhabited the Bandiagara Escarpment in Mali from the 11th through 16th centuries CE.

Introduction: The Dogon People

The Dogon are an ethnic group living in the central plateau region of the country of Mali, in the West of the African continent. They migrated to the region around the 14th century CE. They are best known for their religious traditions, wooden sculpture, architecture, and funeral masquerades. The past century has seen significant changes in the social organization, material culture, and beliefs of the Dogon, partly because Dogon country is one of Mali’s major tourist attractions.

Dogon Sculpture

Dogon art is primarily sculptural and revolves around religious values, ideals, and freedoms. Dogon sculptures are not made to be seen publicly and are commonly hidden from the public eye within the houses of families, sanctuaries, or the hogon (a spiritual leader of the Dogon people). The importance of secrecy is due to the symbolic meaning behind the pieces and the process by which they are made. Dogon sculptures are typically characterized by an elongation of form and a mix of geometric and figurative images.

Dogon Sculpture: Dogon sculptures are typically characterized by an elongation of form and a combination of geometric and figurative images.

Themes

Themes found throughout Dogon sculpture consist of figures with raised arms, superimposed bearded figures, horsemen, stools with caryatids, women with children, figures covering their faces, women grinding pearl millet, women bearing vessels on their heads, donkeys bearing cups, musicians, dogs, quadruped-shaped troughs or benches, figures bending from the waist, mirror-images, apron-wearing figures, and standing figures. Signs of other contacts and origins are evident in Dogon art; the Dogon people were not the first inhabitants of the area, and influence from the Tellem, or the people who inhabited the region in Mali between the 11th and 16th centuries CE, is evident in the use of rectilinear designs.

Dogon art is extremely versatile, although common stylistic characteristics—such as a tendency towards stylization—are apparent on the statues. Their art deals with Dogon myths, whose complex ensembles regulate the life of the individual. The sculptures are preserved in innumerable sites of worship and personal or family altars, and often render the human body in a simplified way, reducing it to its essentials. Many sculptures recreate the silhouettes of the Tellem culture, featuring raised arms and a thick patina, or surface layer, made of blood and millet beer. The Dogon style has evolved into a kind of cubism: ovoid head, squared shoulders, tapered extremities, pointed breasts, forearms and thighs on a parallel plane, and hair stylized by three or four incised lines.

Uses

Dogon sculptures serve as a physical medium in initiations and as an explanation of the world. They serve to transmit an understanding to the initiated, who will decipher the statue according to the level of their knowledge. Carved animal figures, such as dogs and ostriches, are placed on village foundation altars to commemorate sacrificed animals, while granary doors, stools, and house posts are also adorned with figures and symbols. Kneeling statues of protective spirits are placed at the head of the dead to absorb their spiritual strength and to be their intermediaries with the world of the dead, into which they accompany the deceased before once again being placed on the shrines of the ancestors.

Mendé Masks

Mendé masks are commonly used in initiation ceremonies into secret Poro and Sande societies.

Learning Objectives

Discuss how Mendé masks are created and used by the Mendé people

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Mendé people are one of the two largest ethnic groups in Sierra Leone; they belong to a larger group of Mandé peoples who live throughout West Africa.

- The masks associated with the secret societies of the Mendé are probably the best known and most finely crafted in the region.

- Masks represent the collective mind of Mendé community; viewed as one body, they are seen as the Spirit of the Mendé people.

- The most important masks personify and embody the powerful spirits belonging to the medicine societies: the goboi and gbini of the Poro society (the secret society for men) and the sowei of the Sande society (the secret society for women).The features of a Sowei mask convey Mendé ideals of female morality and physical beauty; they are somewhat unusual because women wear the masks.

Key Terms

- hale: Secret societies of the Mendé people.

Background and Art of the Mendé People

The Mendé people are one of the two largest ethnic groups in Sierra Leone, having roughly the same population as their neighbours the Temne people. Together, the Mendé and Temne both account for slightly more than 30% of the country’s total population. The Mendé belong to a larger group of Mande peoples who live throughout West Africa. Mostly farmers and hunters, the Mendé are divided into two groups: the halemo (or members of the hale or secret societies) and the kpowa (people who have never been initiated into the hale). The Mendé believe that all humanistic and scientific power is passed down through the secret societies.

Mendé art is primarily found in the form of jewelry and carvings. The masks associated with the secret societies of the Mendé are probably the best known and are finely crafted in the region. The Mendé also produce beautifully woven fabrics, which are popular throughout western Africa, and gold and silver necklaces, bracelets, armlets, and earrings. The bells on the necklaces are of the type believed capable of being heard by spirits, ringing in both worlds, that of the ancestors and the living.

Mendé Masks

Masks represent the collective mind of the Mendé community; viewed as one body, they are seen as the Spirit of the Mendé people. The Mendé masked figures are a reminder that human beings have a dual existence; they live in the concrete world of flesh and material things as well as in the spirit world of dreams, faith, aspirations, and imagination.

The standard set of Mendé maskers includes about a dozen personalities embodying spirits of varying degrees of power and importance. The most important of these personify and embody the powerful spirits belonging to the medicine societies: the goboi and gbini of the Poro society (the secret society for men), the sowei of the Sande society (the secret society for women), and the njaye and humoi maskers belonging to the eponymous medicine societies. The maskers of the Sande and Poro societies are responsible for enforcing laws and are important symbolic presences in the rituals of initiation and in public ceremonies that mark the coronations and funerals of chiefs and society officials.

Sowei Masks

The features of a Sowei mask convey Mendé ideals of female morality and physical beauty. They are somewhat unusual in that women traditionally wear the masks. The bird on top of the head represents a woman’s intuition that lets her see and know things that others can’t. The high or broad forehead represents good luck or the sharp, contemplative mind of the ideal Mendé woman. Downcast eyes symbolize a spiritual nature, and it is through these small slits that a woman wearing the mask would look out of. The small mouth signifies the ideal woman’s quiet and humble character. The markings on the cheeks are representative of the decorative scars girls receive as they step into womanhood. The neck rolls are an indication of the health of ideal women; they have also been called symbols of the pattern of concentric, circular ripples the Mendé spirit makes when emerging from the water. The intricate hairstyles reveal the close ties within a community of women. The holes at the base of the mask are where the rest of the costume is attached; a woman who wears these masks must not expose any part of her body, or it is believed a vengeful spirit may take possession of her.

When a girl becomes initiated into the Sande society (the Mendé secret society for women), the village’s master woodcarver creates a special mask just for her. Helmet masks are made from a section of tree trunk, often of the kpole (cotton) tree, and then carved and hollowed to fit over the wearer’s head and face. The woodcarver must wait until he has a dream that guides him to make the mask a certain way for the recipient. A mask must be kept hidden in a secret place when no one is wearing it. These masks appear not only in initiation rituals but also at important events such as funerals, arbitrations, and the installation of chiefs.

Helmet Mendé Mask: Helmet masks of the Mendé, Vai, Gola, Bassa and other peoples of the sub-region are the best documented instance of women’s masking in Africa. These masks are used by the Sande association, a powerful organization with social, political and religious significance. Although worn only by women, these masks, as is the case elsewhere in Africa, are carved by men.

Gbini Masks

Gbini is considered to be the most powerful of all Mendé maskers; it appears both at the final ceremony of the Poro initiation process for a son of the paramount chief and also at the coronation of funeral of a paramount chief. Because of its power, women are made to stand far back from gbini and if a woman accidentally touches it, she must be anointed with medicine immediately.

The Gbini wears a large leopard skin, which indicates its association with the paramount chief. The flat, round headpiece resembles the chief’s crown. The headpiece is constructed of animal hide stretched over a bamboo framework, and the hide is decorated with cowrie shells and black, white, and red strips of cloth that are worked into a geometric pattern. At the center is a round mirror. Several flaps that are similarly decorated hang down from the base of the headpiece and overlap the cape, which covers much of the wearer’s torso.

Gbini mask: Gbini mask, Mendé (wood, leopard skin, sheepskin, antelope skin, raffia fiber, cotton cloth, cotton string, cowry shells), from the collection of the Brooklyn Museum.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Contemporary African Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Contemporary_African_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- receptacle. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/receptacle. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Xhosa people. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Xhosa_people. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Africa. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Africa. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Igbo people. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Igbo_people%23Religion_and_rites_of_passage. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Igbo religion. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Igbo_religion. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cultural Anthropology/Ritual and Religion. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Cultural_Anthropology/Ritual_and_Religion. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- African art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/African_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- sanctuaries. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/sanctuaries. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Masque blanc Punu-Gabon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Masque_blanc_Punu-Gabon.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- IMG 2267u201377 b. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:IMG_2267%E2%80%9377_b.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Kalabari Kingdom. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalabari_Kingdom. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ijaw people. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ijaw_people. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Elem Kalabari. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Elem_Kalabari. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Kalabari tribe. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalabari_tribe. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- enculturation. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/enculturation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- kin. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/kin. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Masque blanc Punu-Gabon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Masque_blanc_Punu-Gabon.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- IMG 2267u201377 b. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:IMG_2267%E2%80%9377_b.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- IjoMask1. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:IjoMask1.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- African Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/African_art#Dogon. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Dogon people. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Dogon_people. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- vessel. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/vessel. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tellem. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tellem. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Masque blanc Punu-Gabon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Masque_blanc_Punu-Gabon.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- IMG 2267u201377 b. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:IMG_2267%E2%80%9377_b.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- IjoMask1. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:IjoMask1.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Dogon sculpture Louvre 70-1999-9-2. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dogon_sculpture_Louvre_70-1999-9-2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Masquerade in Mende Culture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Masquerade_in_Mende_culture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mende people. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mende_people%23Arts. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mende people. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mende_people. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com//art-history/definition/hale. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Masque blanc Punu-Gabon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Masque_blanc_Punu-Gabon.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- IMG 2267u201377 b. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:IMG_2267%E2%80%9377_b.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- IjoMask1. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:IjoMask1.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Dogon sculpture Louvre 70-1999-9-2. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dogon_sculpture_Louvre_70-1999-9-2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- WLA ima Mende People helmet mask for Sande association. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WLA_ima_Mende_People_helmet_mask_for_Sande_association.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 1024px-Brooklyn_Museum_2004.77.1_Gbini_Mask.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Masquerade_in_Mende_culture#/media/File:Brooklyn_Museum_2004.77.1_Gbini_Mask.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution