25.4: North America

- Page ID

- 53106

Beadwork and Ceramics in the Eastern Woodland Cultures

The Eastern Woodland cultures lived east of the Mississippi River and are best known for their beadwork and pottery.

Learning Objectives

Compare and contrast the Northeastern and Southeastern Woodland cultures

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Eastern Woodland cultures inhabited the regions of North America east of the Mississippi River. Much of their artwork was preserved in the earthen mounds where they buried their dead.

- Beadwork, pendants, and wood carvings were common among the tribes of the Northeastern Woodlands.

- The art of the Mississippian culture from 800–1500 CE included advanced pottery techniques, patchwork clothing, and wood carving and painting. The culture flourished throughout the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex.

- Fort Ancient culture flourished along the Ohio River from 1000 CE–1750 CE and included coiled pottery, beadwork, and silversmithing.

Key Terms

- effigy: A likeness of a person.

- gorget: An ornament for the neck; a necklace, ornamental collar, torque etc.

- discoidal: Having the flat, circular shape of a disc or a quoit.

Overview: The Eastern Woodland Cultures

The Eastern Woodland cultures inhabited the regions of North America east of the Mississippi River as of 2500 BCE or earlier. Much of their artwork has been preserved through their shared tradition of burying their dead in earthen mounds along with artifacts and tools.

Northeastern Woodlands

From the 12th century onward, the Iroquois and nearby coastal tribes fashioned wampum from shells and string. Wampum is a Wampanoag word referring to the shells themselves, which were used primarily as currency and were highly sought as a trade good throughout the Eastern Woodlands.

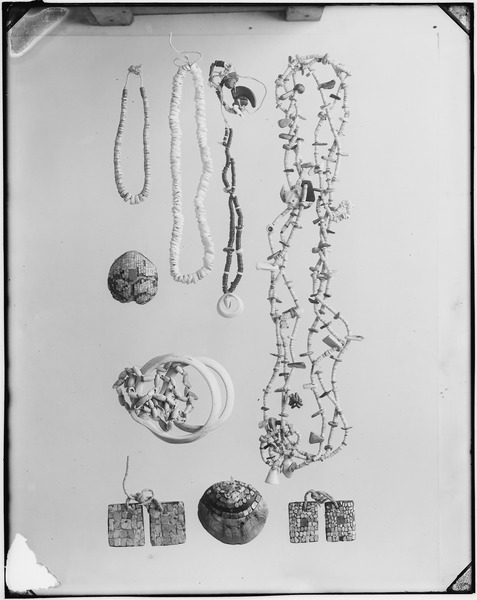

Wampum jewelry: Wampum was commonly traded or used as currency by the Iroquois and nearby coastal tribes.

Beadwork was very popular in this region, and Indigenous peoples produced barrel-shaped and discoidal shell beads, as well as perforated small whole shells. Over time, the use of more slender iron drills greatly improved the drilling of holes in small beads. Pendants carved from stone, wood, shells, and incised animal teeth—especially bear teeth—were popular and were typically shaped as animals such as birds, turtles, or fish. Bird motifs were especially common—ranging from the stylized heads of raptors to ducks—as were images of human faces, believed by the Seneca and other tribes to be protective. Pearls were historically inlaid into bear teeth and incorporated into necklaces.

Other arts from the Northeast Woodlands included wood carvings, such as False Face masks used by Iroquois people in healing rituals. Iroquois artists carved ornamental hair combs from antlers, making increasingly elaborate designs with the introduction of metal knives from Europe in the late 16th and 17th centuries. Europeans also introduced silversmithing to the northeast in the mid-17th century, and today there are several active Iroquois silversmiths.

Southeastern Woodlands

Mississippian Culture

The Mississippian culture flourished from approximately 800–1500 CE in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States. Pottery is one of the hallmark arts of this culture, which includes the Cahokia, Natchez, Caddo, Choctaw, Muscogee Creek, Wichita, and many other southeastern peoples. One of the defining marks of Mississippian culture pottery is its use of more advanced ceramic techniques, such as the use of ground mussel shell as a tempering agent in the clay paste. Textile making (such as the common patchwork clothing worn by indigenous people) and doll-making were also common crafts.

Mississippi pottery: A human head effigy pot from the Mississippian culture, on display at the Hampson Museum State Park in Wilson.

Many artisans from this area were involved with the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, a pan-regional and pan-linguistic religious and trade network. The majority of the information known about the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex is derived from the elaborate artworks its participants left behind, including pottery, shell gorgets and cups, stone statuaries, and copper plates. With the invasion of the Europeans and the diseases they introduced, many of the societies collapsed and ceased to practice a Mississippian lifestyle.

Cherokee shell gorget: A contemporary shell gorget carved by Bennie Pokemire (Eastern Band Cherokee).

In 1896, more than 1,000 carved and painted wooden objects—including masks, tablets, plaques, and effigies —were excavated in Key Marco, southwestern Florida. They have since been described as some of the finest prehistoric Native American art in North America. Spanish missionaries described similar masks and effigies in use by the Calusa late in the 17th century, although no examples of the Calusa objects from the historic period have survived.

Fort Ancient Culture

In addition to Mississippi culture, Fort Ancient was a Native American culture that flourished from 1000–1750 CE among a people who predominantly inhabited land along the Ohio River. Fort Ancient women used a technique known as coiling to make their pottery, in which they rolled clay into long, rounded strips. They then layered these strips one on top of another to mold the vessel, smoothing the inside of the vessel with a smooth round stone and the outside with a wooden paddle. Pottery from this period was distinguished by thinner walls than preceding Woodland pottery, and common shapes included large plain cooking jars with straps or loop handles. Fort Ancient pottery was often engraved with decorations on the rim and neck of the vessels, consisting of a series of interlocking lines, called guilloché.

Traditional dress often incorporated elaborate designs and decorations. For example, Choctaw women’s dance regalia incorporated ornamental silver combs and openwork beaded collars, and Caddo women wore hourglass-shaped hair ornaments called dush-tohs.

Clay, stone, and pearl beads were fashioned and worn by the people of the Southeastern Woodlands, often decorated with bold imagery. As in the North, European contact introduced glass beads and silversmithing technology, and silver and brass armbands and gorgets became popular among Southeastern men in the 18th and 19th centuries. Sequoyah became one of the first well-known Cherokee silversmiths in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Arts of the Great Plains

Great Plains Native Americans are well known for their buffalo hide paintings, quillwork, and elaborate beadwork.

Learning Objectives

Examine the influence of European contact on buffalo hide painting, beadwork, metalsmithing, and other kinds of Great Plains art

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The people of the Great Plains are the indigenous peoples who live on the plains and rolling hills of the Great Plains of North America.

- Buffalo hide clothing of these tribes was beautiful and elaborate, decorated with porcupine quill embroidery, beads, shells, and teeth.

- Buffalo hide paintings—and its later counterpart, Ledger Art—illustrated narratives, pictorial designs, calendars, and geometric designs.

- Great Plains Native Americans are perhaps most well known for their beadwork, used to decorate clothing, jewelry, breastplates, and ceremonial headdresses.

Key Terms

- pictographic: Represented by illustrations.

- nomadic: Leading a wandering life with no fixed abode; peripatetic, itinerant.

- quillwork: Decorative textile embellishment made from porcupine quills by certain Native Americans.

Overview: The Great Plains Cultures

The people of the Great Plains are the indigenous peoples who live on the plains and rolling hills of the Great Plains of North America. During the Plains Village period (ca. 950–1850 CE), tribes included nomadic peoples, such as the Blackfoot, Arapaho, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Comanche, Crow, Gros Ventre, Kiowa, Lakota Sioux, Lipan, Plains Apache (or Kiowa Apache), Plains Cree, Plains Ojibwe, Sarsi, Nakoda (Stoney), and Tonkawa. Tribes also included the semi-sedentary tribes of the Arikara, Hidatsa, Iowa, Kaw (or Kansa), Kitsai, Mandan, Missouria, Omaha, Osage, Otoe, Pawnee, Ponca, Quapaw, Wichita, and the Santee, Yanktonai, and Yankton Sioux.

Art of the Great Plains

Buffalo Hides

Buffalo hide has many uses in Great Plains art. Clothing made from buffalo hide was beautiful and elaborate, decorated with porcupine quill embroidery (using a traditional style known as porcupine quillwork ), beads, and such prized materials as shells and elk teeth. Later, items such as coins and glass beads acquired from trading were incorporated into Plains art.

Traditional Sioux dress: Sioux dress with fully beaded yoke.

Painting on buffalo hides was a common practice as well. Men painted narrative, pictorial designs recording personal exploits or visions as well as pictographic historical calendars known as Winter counts. Women painted geometric designs on tanned robes and rawhide, which sometimes served as maps. During the Reservation Era of the late 19th century, buffalo herds were systematically destroyed by European hunters. Due to the scarcity of hides, Plains artists adopted new painting surfaces, such as muslin or paper, giving birth to Ledger Art. Ledger Art flourished from the 1860s to the 1920s and was named for the accounting ledger books that were a common source for paper for Plains Native Americans during the late 19th century.

Beadwork

Great Plains Native Americans are most well known for their beadwork, which dates back to 8800 BCE and was used to decorate chokers, breastplates, clothing, jewelry, and ceremonial headdresses worn by women and men. Shells, such as marginella and olivella shells, were traded from the Gulf of Mexico and the coasts of California to the Plains beginning in 100 CE, and mussel shell gorgets, dentalia, and abalone were prized trade items for jewelry. Bones provided material for beads as well, especially long, cylindrical beads called hair pipes. Porcupine quillwork was also used in creating bracelets, hatbands, belt buckles, headdresses, hair roaches, and hair clips.

Glass beads were first introduced to the Plains as early as 1700 and were used in decoration in a manner similar to quillwork, though they never fully replaced it. The Lakota, especially the members of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe in the Western Dakotas, became particularly adept at glass bead work. Several award-winning quillworkers are active in the art world today, such as Juanita Growing Thunder Fogarty (Assiniboine-Sioux).

Metalsmithing

Southern Plains Native Americans adopted metalsmithing in the 1820s, after metal jewelry was introduced through Spanish and Mexican metalsmiths and trade with tribes from other regions. Plains men began wearing metal pectorals and armbands, and in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, members of the Native American Church revealed their membership to others through pins with emblems of peyote buttons, water birds, and other religious symbols. Bruce Caesar (Sac and Fox-Pawnee) is one of the most prolific Southern Plains metalsmiths active today and was awarded the NEA’s National Heritage Fellowship in 1998. U.S. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell (Northern Cheyenne) is also an accomplished silversmith.

Woodcarving in the Northwest Coast Cultures

Art from the indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast and Alaska is distinguished by its complex woodcarvings and its use of formline.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the effects of European contact on the art produced in the Northwest coast and Alaska

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Northwest Coast art refers to art created by the indigenous peoples of present-day Washington State, Oregon, British Columbia, and Alaska.

- Before the European invasion, the most common media used by artists of this region were wood, stone, and copper; since European contact, paper, canvas, glass, and precious metals also have been used.

- Totem poles, masks, and canoes are examples of the complex woodcarvings of the peoples of the Northwest.

- Totem poles are monumental sculptures carved on poles, posts, or pillars with symbols or figures that commemorate cultural beliefs, recount familiar legends or events, or identify clan lineages; they may also serve as functional architectural features.

- Northwest designs commonly included natural animals, legendary creatures, and abstract forms and shapes, and they were often used to decorate traditional household items.

- After the arrival of Europeans in the late 18th century, traditional production of Northwest Coast art dropped significantly due to population loss and cultural assimilation.

Key Terms

- First Nation: The indigenous peoples of any country or region.

- formline: A feature in the indigenous art of the Northwest Coast of North America, distinguished by the use of characteristic shapes referred to as ovoids, U forms, and S forms.

- argillite: A fine-grained sedimentary rock, intermediate between shale and slate, sometimes used as a building material.

Northwest Coast Art

Northwest Coast art is the term commonly applied to a style of art created primarily by artists from Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, and other First Nations and Native American tribes along the Northwest Coast of North America, from pre-European invasion times up to the present. Art from this region is historically distinguished by complex woodcarvings and the use of formlines, or characteristic shapes referred to as ovoids, “U” forms, and “S” forms.

Woodcarvings

Before the European invasion, the most common media were wood (often Western red cedar), stone, and copper; since European contact, paper, canvas, glass, and precious metals have also been used. If paint was used to decorate an object, the most common colors were traditionally red and black, though yellow was often used as well, particularly among Kwakwaka’wakw artists. Woodcarving from this region is characterized by an extremely complex style. The most famous examples include Totem poles, Transformation masks, and canoes.

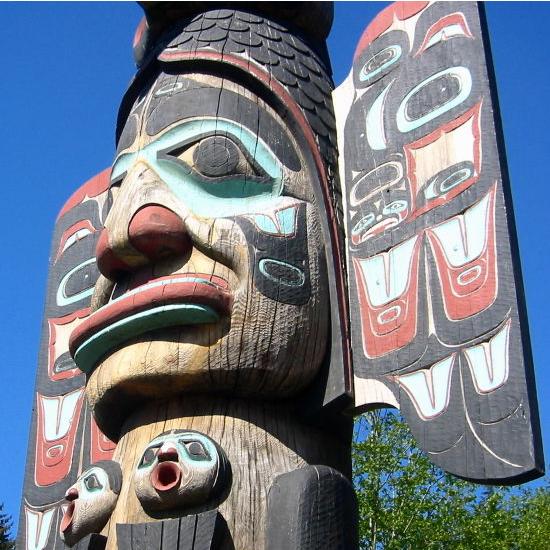

Totem Pole from the Northwest: Native American Totem Pole from Ketchikan, Alaska.

Totem Poles

Totem poles are monumental sculptures carved on poles, posts, or pillars with symbols or figures made from large trees (mostly western red cedar) by indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest coast. The word totem derives from the Algonquian (most likely Ojibwe) word odoodem, “his kinship group.” The carvings may symbolize or commemorate cultural beliefs that recount familiar legends, clan lineages, or notable events. The poles may also serve as functional architectural features, welcome signs for village visitors, or mortuary vessels for the remains of deceased ancestors. Given the complexity and symbolic meanings of totem pole carvings, their placement and importance lies in the observer’s knowledge and connection to the meanings of the figures.

Totem pole carvings were likely preceded by a long history of decorative carving, with stylistic features borrowed from smaller prototypes. Eighteenth century European invaders documented the existence of decorated interior and exterior house posts prior to 1800. United States governmental policies and practices of acculturation and assimilation sharply reduced totem pole production by the end of 19th century. Renewed interest from tourists, collectors, and scholars in the 1880s and 1890s helped document and collect the remaining totem poles, but nearly all totem pole making had ceased by 1901. Twentieth century revivals of the craft, additional research, and continued support from the public have helped establish new interest in this regional artistic tradition.

Weaving and Other Art Forms

Chilkat weaving applied formline designs to their textiles. Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian have traditionally produced Chilkat woven regalia from wool and yellow cedar bark, using them for civic and ceremonial events.

Chilkat blanket: In the collection of the University of Alaska Museum, Fairbanks.

The patterns depicted in most forms of art include natural forms, such as bears, ravens, eagles, orcas, and humans; legendary creatures, such as thunderbirds and sisiutls; and abstract forms made up of the characteristic Northwest Coast shapes. Northwest Coast designs were often used to decorate traditional household items, such as spoons, ladles, baskets, hats, and paddles; following European contact, the Northwest Coast art style has increasingly been used in gallery-oriented forms, such as paintings, prints, and sculptures.

Impact of Europeans

After the European invasion in the late 18th century, the people who produced Northwest Coast art suffered huge population losses due to diseases, such as smallpox, and cultural losses due to assimilation into European-North American culture. The production of their art dropped off drastically as well. Toward the end of the 19th century, Northwest Coast artists began producing work for commercial sale, such as small argillite carvings. The end of the 19th century also saw a large-scale export of totem poles, masks, and other traditional art objects from the region to museums and private collectors around the world. Some of this export was accompanied by financial compensation to people who had a right to sell the art, though a great deal was not.

In the early 20th century, very few First Nations artists in the Northwest Coast region were producing art. A tenuous link to older traditions remained in artists such as Charles Gladstone and Mungo Martin. The mid-20th century saw a revival of interest and production of Northwest Coast art due to the influence of artists and critics, such as Bill Reid, a grandson of Charles Gladstone. It also saw an increasing demand for the return of art objects that were illegally taken from First Nations communities—a demand that continues to the present day. Today, there are numerous art schools teaching formal Northwest Coast art of various styles, and there is a growing market for new art in this style.

Art and Architecture of the Southwest Cultures

The indigenous peoples of the Southwest created magnificent works of pottery, jewelry, painting, weaving, and architecture.

Learning Objectives

Describe the pottery and jewelry of the Ancestral Pueblo, the sandpainting and weaving of the Navajo, and the architecture of the Southwest region

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Anasazi, or Ancestral Pueblo, created grayware and black-on-white pottery, decorated with geometric designs or representations of people, animals, and birds.

- Pueblo jewelry was often inlaid with pieces of turquoise, stone, or shell, and the Navajo incorporated silversmithing into their jewelry-making after this practice was introduced by the Mexicans in the 1850s.

- Sandpainting, the art of pouring colored sand onto a surface, was an aspect of Navajo healing ceremonies.

- Navajos learned to weave on upright looms from Pueblos and wove blankets and rugs that were highly regarded around the region.

- The Ancient Pueblo culture is perhaps best known for the stone and adobe dwellings built along cliff walls, the most elaborate of which is Chaco Canyon in New Mexico.

Key Terms

- adobe: An unburnt brick dried in the sun; a house made of unburnt brick dried in the sun.

- lapidary: An artist or artisan who forms stone, minerals, or gemstones into decorative items such as engraved gems, including cameos and faceted designs; the primary techniques employed are cutting, grinding, and polishing.

- cabochon: A gemstone that has been shaped and polished as opposed to faceted.

- inlay: To place pieces of a foreign material within another material to form a decorative design.

- lignite: A low-grade, brownish-black coal.

- Utilitarian: Practical and functional, not just for show.

Overview: The Art of the Southwest

Prior to the European invasion of North America, the region of the Southwest was dominated by the Pueblo, Navajo, Apache, Hopi, and Zuni peoples, among others. These peoples were rich in culture and history, creating magnificent works of pottery, jewelry, painting, weaving, and architecture. The Anasazi, or Ancestral Pueblo (1000 BCE–700 CE), are the ancestors of today’s Pueblo tribes. Their culture formed in the American southwest, after the cultivation of corn was introduced from Mexico around 1200 BCE. People of this region developed an agrarian lifestyle, cultivating food, storage gourds, and cotton with irrigation or xeriscaping techniques. They lived in sedentary towns, so pottery, used to store water and grain, was ubiquitous.

Pottery

For hundreds of years, the Pueblo created utilitarian grayware and black-on-white pottery, incorporating reds and oranges toward the end of their era in the 13th century. Designs were painted on the exterior of black-on-white pottery and the interior of bowls, primarily with geometric shapes or representations of people, animals, and birds. Pottery making became an art form for individuals who specialized in distinctive styles made for trade. The Hopi were known for creating ollas, dough bowls, and food bowls of different sizes for daily use; they also made more elaborate ceremonial mugs, jugs, ladles, seed jars, and vessels for ritual use. These finer works were usually finished with polished surfaces and decorated with black painted designs.

Pottery of the Pueblo: Ceramic bowl with painted geometric shapes on the inside, from Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, Pueblo III phase.

Jewelry and Silversmithing

Jewelry and other ornaments were made by the Pueblo using shells and stones bartered from the coasts of Mexico and California. Within the region, turquoise, soapstone, and lignite were attained through trade. Just as pottery from this period has received world-wide recognition, work inlaid with shell and turquoise from this period was noteworthy for its artistry and sophisticated inlay techniques.

Old and new turquoise Navajo bracelets: The Navajo are well-known today for their use of turquoise in jewelry.

In the 1850s, the Navajos adopted silversmithing from the Mexicans. Atsidi Sani (Old Smith) was the first Navajo silversmith, and the technology quickly spread to surrounding tribes. Today, thousands of artists produce silver jewelry using turquoise. Their hallmark jewelry piece known as the squash blossom necklace first appeared in the 1880s; while turquoise had been part of jewelry for centuries, Navajo artists did not use inlay techniques to insert turquoise into silver designs until the late 19th century. Sikyatata became the first Hopi silversmith in 1898, and Hopi are renowned for their overlay silver work and cottonwood carvings. Zuni artists are admired for their cluster work jewelry showcasing turquoise designs, as well as for their elaborate, pictorial stone inlay in silver.

The centuries-old art of lapidary, preserved by clan and family tradition, remains an important element of design. These works of art are commonly decorated with stone on stone mosaic inlay, channel inlay, cluster work, petite point, needle point, and natural cut or smoothed and polished cabochons fashioned from shells, coral, semi-precious gems, and precious gems; as with other art forms, blue or green turquoise is the most common and recognizable material used.

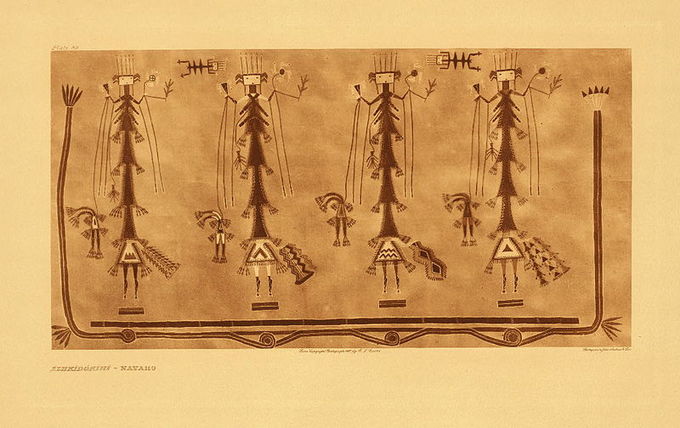

Navajo Sandpainting

Sandpainting is an aspect of Navajo healing ceremonies that inspired an art form. It involves the pouring of colored sands, powdered pigments from minerals or crystals, and pigments from other natural or synthetic sources onto a surface to make a fixed or unfixed kind of painting. In the sandpainting of southwestern Navajo, the Medicine Man (or Hatałii) paints loosely upon the ground of a hogan, where the ceremony takes place, or on a buckskin or cloth tarpaulin, by letting the colored sands flow through his fingers. The colors for the painting are usually accomplished with naturally colored sand, crushed gypsum (white), yellow ochre, red sandstone, charcoal, and a mixture of charcoal and gypsum (blue). Brown can be made by mixing red and black; red and white make pink. Other coloring agents include corn meal, flower pollen, or powdered roots and bark.

Navajo sandpainting: One of the four elaborate dry-paintings or sand altars employed in the rites of the Mountain Chant, a Navaho medicine ceremony of nine days’ duration.

Weaving

Navajos came to the southwest with their own weaving traditions; however they learned to weave on upright looms from Pueblos and wove blankets that were eagerly collected by Great Basin and Plains tribes in the 18th and 19th centuries. After the introduction of the railroad in the 1880s, imported blankets became plentiful and inexpensive, so Navajo weavers switched to producing rugs for trade for an increasingly non-Native audience. Rail service also brought in Germantown wool from Philadelphia, a kind of commercially dyed wool, which greatly expanded the weavers’ color palettes. Some early European-American invaders moved in and set up trading posts, often buying Navajo rugs by the pound and selling them back east by the bale.

Architecture

The Anasazi culture is perhaps best known for the stone and adobe dwellings built along cliff walls, particularly during the Pueblo II (900–1150 CE) and Pueblo III (1150–1350 CE) eras. Adobe structures are constructed with bricks created from sand, clay, and water, with some fibrous or organic material; they were then shaped using frames and dried in the sun. These villages, called pueblos by Spanish settlers, were often only accessible by rope or rock climbing. One of the most elaborate and largest ancient settlements is Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, which includes 15 major complexes of sandstone and timber connected by a network of roads.

In the Southwestern United States, numerous pictographs and petroglyphs were created. The creations of the Fremont culture, the Anasazi, and later tribes can be seen at present day Buckhorn Draw Pictograph Panel and Horseshoe Canyon, among other sites. Petroglyphs by these and the Mogollon culture’s artists are represented in Dinosaur National Monument and at Newspaper Rock.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mississippian culture pottery. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mississippian_culture_pottery. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ceramics of indigenous peoples of the Americas. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ceramics_of_indigenous_peoples_of_the_Americas%23Eastern_Woodlands. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Fort Ancient. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Ancient%23Ceramics. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Native American jewelry. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_American_jewelry. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Native Americans in the United States. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_Americans_in_the_United_States%23Society_and_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Visual arts by indigenous peoples of the Americas. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Visual_arts_by_indigenous_peoples_of_the_Americas%23Eastern_Woodlands. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- discoidal. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/discoidal. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- gorget. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/gorget. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- effigies. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/effigies. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bennie pokemire gorget. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bennie_pokemire_gorget.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Hampson effigypot HRoe 2006. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hampson_effigypot_HRoe_2006.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Wampum jewelry - NARA - 523576.tif. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wampum_jewelry_-_NARA_-_523576.tif. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Ledger art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ledger_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Plains Indians. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Plains_Indians. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Visual arts by indigenous peoples of the Americas. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Visual_arts_by_indigenous_peoples_of_the_Americas%23The_West. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Native American jewelry. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_American_jewelry%23Great_Plains. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- quillwork. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/quillwork. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- nomadic. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/nomadic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- pictographic. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pictographic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bennie pokemire gorget. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bennie_pokemire_gorget.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Hampson effigypot HRoe 2006. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hampson_effigypot_HRoe_2006.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Wampum jewelry - NARA - 523576.tif. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wampum_jewelry_-_NARA_-_523576.tif. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Sioux-Womendress. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sioux-Womendress.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Northwest Coast art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Northwest_Coast_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Native American jewelry. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_American_jewelry%23Northwest_Coast. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Visual arts by indigenous peoples of the Americas. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Visual_arts_by_indigenous_peoples_of_the_Americas%23Northwest_Coast. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- argillite. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/argillite. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- First Nation. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/First_Nation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Totem pole. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Totem_pole. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bennie pokemire gorget. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bennie_pokemire_gorget.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Hampson effigypot HRoe 2006. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hampson_effigypot_HRoe_2006.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Wampum jewelry - NARA - 523576.tif. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wampum_jewelry_-_NARA_-_523576.tif. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Sioux-Womendress. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sioux-Womendress.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chilkat blanket univ alaska museum. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Chilkat_blanket_univ_alaska_museum.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Ketchican totem pole 2 stub. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ketchican_totem_pole_2_stub.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Boundless. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com//management/definition/utilitarian. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Native American jewelry. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_American_jewelry%23Southwest. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ancestral Pueblo. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancestral_Pueblo. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Native Americans in the United States. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_Americans_in_the_United_States%23Society_and_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pueblo III Era. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Pueblo_III_Era. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sandpainting. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Sandpainting. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Native American art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_American_art%23Southwest. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Navajo people. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Navajo_people. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- adobe. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/adobe. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- lignite. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/lignite. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- inlay. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/inlay. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bennie pokemire gorget. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bennie_pokemire_gorget.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Hampson effigypot HRoe 2006. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hampson_effigypot_HRoe_2006.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Wampum jewelry - NARA - 523576.tif. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wampum_jewelry_-_NARA_-_523576.tif. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Sioux-Womendress. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sioux-Womendress.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chilkat blanket univ alaska museum. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Chilkat_blanket_univ_alaska_museum.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Ketchican totem pole 2 stub. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ketchican_totem_pole_2_stub.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Navajo sandpainting. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Navajo_sandpainting.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 080. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:080.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bowl Chaco Culture NM USA. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bowl_Chaco_Culture_NM_USA.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright