24.3: The Edo Period

- Page ID

- 53101

Rinpa School Painting in the Edo Period

In the early years of the Edo period, some of Japan’s finest expressions in painting were produced by the Rinpa School.

Learning Objectives

Identify key attributes of Rinpa painting during the Edo period

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- In the early years of the Edo period, the full impact of Tokugawa policies had not yet been felt, and some of Japan’s finest expressions in architecture and painting were produced by the Rinpa School.

- Rinpa artists worked in various formats, notably screens, fans, hanging scrolls, woodblock printed books, lacquerware, ceramics, and kimono textiles. Many Rinpa paintings were used on the sliding doors and walls (fusuma) of noble homes.

- In 1615, Hon’ami Kōetsu founded the Rinpa School of painting by establishing an artistic community of craftsmen supported by wealthy merchant patrons in northeastern Kyoto.

- Kōetsu’s collaborator, Tawaraya Sōtatsu, maintained an atelier in Kyoto and produced commercial paintings such as decorative fans and folding screens; Sōtatsu specialized in decorated paper, to which Kōetsu added calligraphy.

- Like Kōetsu, Sōtatsu pursued the classical Yamato-e genre, but he also pioneered a new technique with bold outlines and striking color schemes.

- The Rinpa School was revived in the Genroku era (1688–1704) by Ogata Kōrin and Ogata Kenzan; Kōrin’s innovation was to depict nature as an abstract using numerous color and hue gradations and mixing colors on the surface to achieve eccentric effects.

Key Terms

- lacquerware: A decorative object coated with lacquer.

- swordsmith: A maker of swords.

Background: The Edo Period

In the Edo (江) or Tokugawa (徳) period between 1603 to 1868, Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, a form of military rule headed by the shogun. The period was characterized by economic growth, strict social order, isolationist foreign policies, increased environmental protection, and popular enjoyment of the arts. It was officially established in Edo on March 24, 1603 by Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616). The period came to an end with the Meiji Restoration on May 3, 1868, after the fall of Edo to forces loyal to the Emperor.

One of the dominant themes in the Edo period was the repressive policies of the shogunate and the attempts of artists to escape these strictures. The foremost of these strictures was the closing of the country to foreigners and the imposition of strict codes of behavior affecting many aspects of life, including the clothes one wore, the person one married, and the activities one could or should not pursue. In the early years of the Edo period, however, the full impact of Tokugawa policies had not yet been felt, and some of Japan’s finest expressions in architecture and painting were produced by the Rinpa School.

The Rinpa School

Style and Technique

Rinpa artists worked in various formats, notably screens, fans, hanging scrolls, woodblock printed books, lacquerware, ceramics, and kimono textiles. Many Rinpa paintings were used on the sliding doors and walls (fusuma) of noble homes. Subject matter and style were often borrowed from Heian period traditions of Yamato-e, with elements from Muromachi ink paintings, Chinese Ming Dynasty flower-and-bird paintings, and Momoyama period Kanō School developments. The stereotypical standard painting in the Rinpa style involves simple natural subjects such as birds, plants, and flowers with the background filled in with gold leaf. Emphasis on refined design and technique became more pronounced as the Rinpa style developed.

Development of the School

Rinpa is one of the major historical schools of Japanese painting. In 1615, Hon’ami Kōetsu founded an artistic community of craftsmen, supported by wealthy merchant patrons of the Nichiren Buddhist sect at Takagamine in northeastern Kyoto. Merchants, who were the lowest of the four social classes and often considered unproductive members of society, were increasingly relied on by the samurai for the production of consumer goods and artistic works. Both the affluent merchant town elite and the old Kyoto aristocratic families favored arts that followed classical traditions, and Kōetsu obliged by producing numerous works of ceramics, calligraphy, and lacquerware. Kōetsu’s collaborator, Tawaraya Sōtatsu, maintained an atelier in Kyoto and produced commercial paintings such as decorative fans and folding screens. Sōtatsu specialized in making decorated paper with gold or silver backgrounds, which Kōetsu assisted by adding calligraphy.

The Founders: Hon’ami Kōetsu and Tawaraya Sōtatsu

Both artists came from families of cultural significance. Kōetsu came from a family of swordsmiths who had served the imperial court and great warlords and shoguns. Kōetsu’s father evaluated swords for the Maeda clan, as did Kōetsu himself. However, Kōetsu was less concerned with swords and more interested in painting, calligraphy, lacquerwork, and the Japanese tea ceremony (he later created several Raku ware tea bowls). His own painting style was flamboyant, recalling the aristocratic style of the Heian period.

Sōtatsu also pursued the same classical Yamato-e genre as Kōetsu, but he pioneered a new technique with bold outlines and striking color schemes. Two of his most famous works include the folding screens Wind and Thunder Gods (風 Fūjin Raijin-zu), located in Kennin-ji temple in Kyoto, and Matsushima (松) at the Freer Gallery in Washington, DC.

Early Rinpa School work: Portion of Sōtatsu’s Fūjin Raijin-zu (Wind and Thunder Gods). 17th century.

Ogata Kōrin and Ogata Kenzan

The Rinpa school was revived in the Genroku era (元 1688–1704) by Ogata Kōrin and his younger brother Ogata Kenzan, sons of a prosperous Kyoto textile merchant. Kōrin’s innovation was to depict nature as an abstract, using numerous color and hue gradations, mixing colors on the surface to achieve eccentric effects, and liberally using precious substances like gold and pearl.

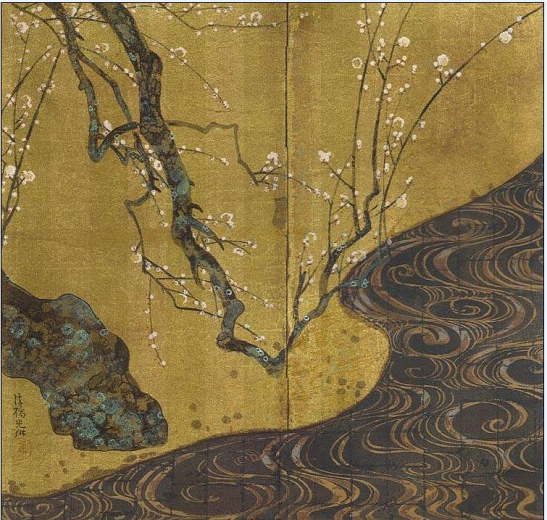

Kōrin’s masterpiece Red and White Plum Trees (紅 Kōhakubai-zu, c. 1714–15) is now at the MOA Museum of Art in Atami, Shizuoka. As a dramatic composition, it established the direction of Rinpa for the remainder of its history. Kōrin collaborated with Kenzan in painting designs and calligraphy on his brother’s pottery. Kenzan remained a potter in Kyoto until after Kōrin’s death in 1716, when he began to paint professionally. Other Rinpa artists active in this period were Tatebayashi Kagei, Tawaraya Sōri, Watanabe Shikō, Fukae Roshū, and Nakamura Hōchū.

Portion of Ogata Kōrin’s Kōhakubai-zu: Kōrin’s Red and White Plum Trees (1714–15) established the direction of Rinpa for the remainder of its history.

Sakai Hōitsu

Rinpa was revived again in 19th century Edo by Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828), a Kanō School artist whose family had been one of Ogata Kōrin’s sponsors. Sakai published a series of 100 woodcut prints based on paintings by Kōrin, and his painting Summer and Autumn Grasses (夏 Natsu akikusa-zu) is painted on the back of Kōrin’s Wind and Thunder Gods screen and is now at the Tokyo National Museum.

Kanō School Painting in the Edo Period

The Kanō School, which had a naturalistic style, was the dominant style of the Edo period (1603 – 1868).

Learning Objectives

Describe the defining characteristics of the Kano School during the Edo Period, and distinguish it from literati painting

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Kanō School began by reflecting a renewed influence from Chinese painting, and it continued to produce monochrome brush paintings in the Chinese style over the years.

- However, the school simultaneously developed a brightly colored and firmly outlined style for large panels, which reflected distinctively Japanese traditions.

- The school was supported by the shogunate, effectively representing an official style of art; under the Edo period in which art and culture were strictly regulated, this essentially monopolized the field of painting.

- Kanō School artists worked mainly for the nobility, shoguns, and emperors, covering a wide range of styles, subjects, and formats.

- While initially innovative, from the 17th century onward, the artists of the school became increasingly conservative and academic in their approach.

Key Terms

- Kanō school: One of the most famous schools of Japanese painting, and the dominant style of painting from the late 15th century until 1868, when the Meiji period began.

- literati: Well-educated, literary people; intellectuals who are interested in literature.

Overview: The Kanō School

The Kanō School (狩) was the dominant style of painting during the Edo period. The Kanō family itself produced a series of major artists over several generations, and a large number of unrelated artists trained in workshops of the school. Some artists married into the family and changed their names, while others were adopted, creating a family known for its artistic innovations.

The Style of the School

The school began by reflecting a renewed influence from Chinese painting, and it continued to produce monochrome brush paintings in the Chinese style over the years. However, it simultaneously developed a brightly colored and firmly outlined style for large panels, which reflected distinctively Japanese traditions. Kanō Motonobu, a Japanese painter and member of the Kano School, is particularly known for expanding the school’s repertoire through his bold artistic techniques and patronage. Many of the works during this period combined the forceful quality of work from the earlier Momoyama period with the tranquil depiction of nature and more refined use of color typical of the current Edo period.

The school was supported by the shogunate, effectively representing an official style of art; under the Edo period in which art and culture were strictly regulated, this essentially monopolized the field of painting. The Kanō School drew on the Chinese tradition of literati painting by scholar-bureaucrats, but the Kanō painters were firmly professional artists: they were very generously paid if successful and received formal workshop training in the family workshop (similar to European painters of the Renaissance or Baroque period). Kanō painters worked primarily for the nobility, shoguns, and emperors, covering a wide range of styles, subjects, and formats. While initially innovative, from the 17th century onward, the artists of the school became increasingly conservative and academic in their approach.

Kanō Tan’yu, Spring Landscape (1672): Tan’yū headed the Kajibashi branch of the Kanō School in Edo and painted in many castles, including the Imperial palace. He used a less bold but extremely elegant style, which tended to become stiff and academic in the hands of less talented imitators.

The range of forms, styles, and subjects that were established in the early 17th century continued to be developed and refined without major innovation for the next two centuries. Although the Kanō School was the most successful in Japan, the distinctions between its work and the work of other schools tended to diminish over time, as all schools worked in a range of styles and formats, making the attribution of unsigned works often unclear. By the end of the Edo period and the beginning of the Meiji period (1868), the Kanō School had divided into many different branches.

Japanese Literati Painting in the Edo Period

An important art trend during the Edo period was the bunjinga or Nanga School, a kind of literati painting highly influenced by China literati.

Learning Objectives

Discuss literati painting in Edo Japan and its debt to China

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Japanese bunjinga paintings—usually in monochrome black ink, sometimes with light color, and nearly always depicting Chinese landscapes or similar subjects—were patterned after Chinese literati painting.

- Due to the Edo period policy of sakoku, Japanese literati artists were left with an incomplete view of Chinese literati ideas, and the bunjinga style emerged from a fusion of Chinese and Japanese ideals.

- Japanese literati were not members of an academic, intellectual bureaucracy like their Chinese counterparts; while the Chinese literati were academics aspiring to be painters, the Japanese literati were professionally trained painters aspiring to be academics and intellectuals.

- Bunjinga paintings almost always depicted traditional Chinese subjects, and artists focused almost exclusively on landscapes, birds, and flowers.

- As Japan became exposed to Western culture at the end of the Edo period, many bunjinga artists began to incorporate stylistic elements of Western art into their own.

Key Terms

- sakoku: The foreign relations policy of Japan in which strict regulations were applied to commerce and foreign relations by the shogunate; the policy stated that, with the exception of certain circumstances, no foreigner could enter nor could any Japanese citizen leave the country on penalty of death; the policy was enacted by the Tokugawa shogunate from 1633–39 and remained in effect until 1853, with the arrival of the Black Ships of Commodore Matthew Perry and the forcible opening of Japan to Western trade.

- Bunjinga: A school of Japanese painting that flourished in the late Edo period among artists who considered themselves literati, or intellectuals; also known as Nanga.

Rise of Bunjinga

An important trend in the Edo period was the rise of the bunjinga genre, a kind of literati painting, also known as the Nanga School or Southern Painting school. This genre started as an imitation of Chinese scholar-amateur painters of the Yuan Dynasty, whose works and techniques came to Japan in the mid-18th century. Later bunjinga artists considerably modified both the techniques and the subject matter of this genre to create a blending of Japanese and Chinese styles. Exemplars of this style include Ike no Taiga, Uragami Gyokudo, Yosa Buson, Tanomura Chikuden, Tani Buncho, and Yamamoto Baiitsu.

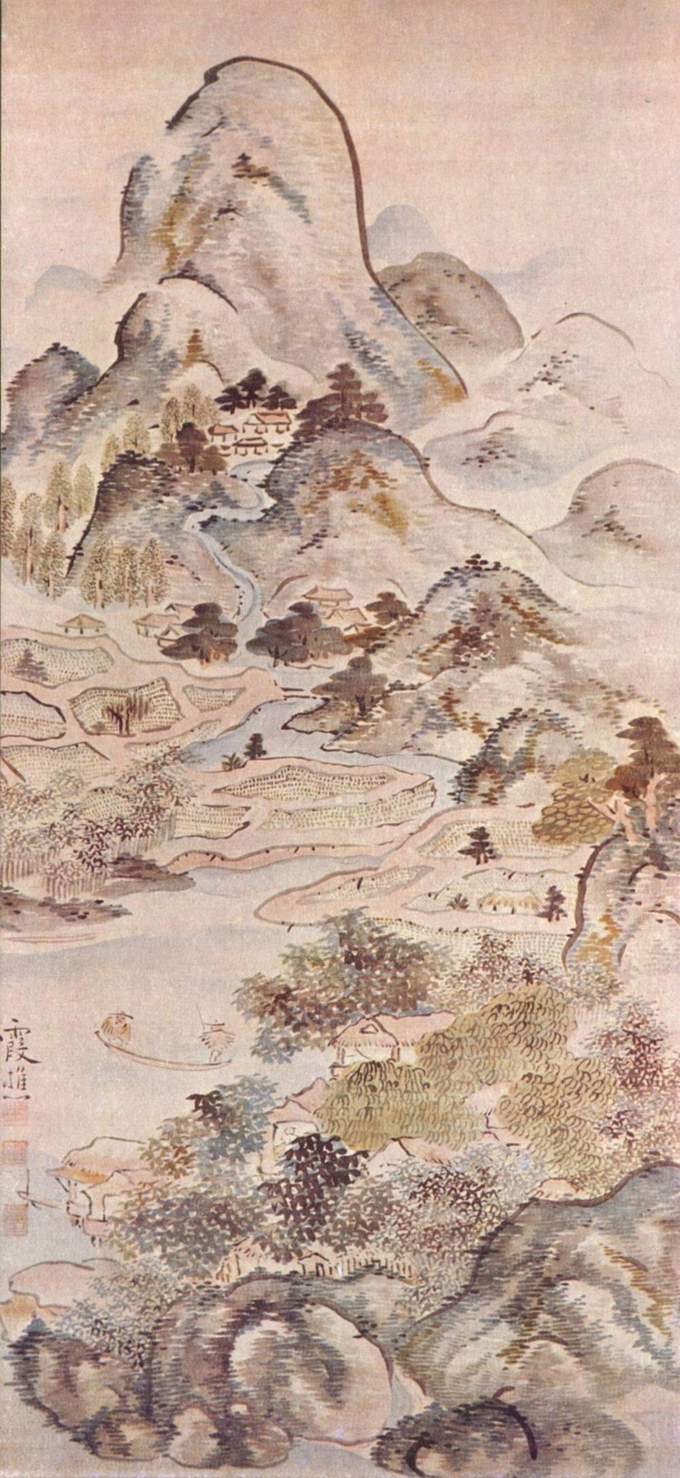

Fishing in Springtime by Ike no Taiga (1747): Bunjinga paintings most often depicted traditional Chinese subjects. Artists focused almost exclusively on landscapes, birds, and flowers.

As part of the Nanga School, the bunjinga style of Japanese painting flourished in the late Edo period among artists who considered themselves literati, or intellectuals. While each of these artists was unique and independent, they all shared an admiration for traditional Chinese culture. Their paintings—usually in monochrome black ink, sometimes with light color, and nearly always depicting Chinese landscapes or similar subjects—were patterned after Chinese literati paintings, called wenrenhua. Poetry or other inscriptions were also an important element of these paintings and were often added by friends of the artist, rather than the artist themselves.

China’s Influence

Chinese literati painting focused on expressing the rhythm of nature rather than the realistic depiction of it. However, the artist was encouraged to display a cold lack of affection for the painting, as if he, as an intellectual, was above caring deeply about his work. Ultimately, this style of painting was an outgrowth of the idea of the intellectual, or literati, as a master of all the core traditional arts—painting, calligraphy, and poetry.

Under the Edo period policy of sakoku, Japan was cut off from the outside world almost completely. Its contact with China persisted, although this was greatly limited. What little did make its way into Japan was either imported through Nagasaki or produced by the Chinese people living there. As a result, the bunjinga artists who aspired to the ideals and lifestyles of the Chinese literati were left with a rather incomplete view of Chinese literati ideas and art. Bunjinga grew, therefore, out of what did come to Japan from China, including Chinese woodblock-printed painting manuals and an assortment of paintings widely ranging in quality.

Yearning for a Pleasurable Place in Mountains of the Heart by Kameda Bôsai, 1816: Kameda Bôsai (1752–1826) was a well-known Japanese literati painter.

Bunjinga was also shaped by the great differences in culture and environment of the Japanese literati as compared to their Chinese counterparts. The form was, to a great extent, defined by its rejection of other major schools of art like the Kano and Tosa Schools. In addition, the literati themselves were not members of an academic, intellectual bureaucracy, as their Chinese counterparts were. While the Chinese literati were academics aspiring to be painters, the Japanese literati were professionally trained painters aspiring to be academics and intellectuals.

Unlike other schools of art that pass on their specific style to their students, every bunjinga artist displayed unique elements in their creations, and many diverged greatly from the stylistic elements employed by their forebears. As Japan became exposed to Western culture at the end of the Edo period, some bunjinga artists began to incorporate stylistic elements of Western art into their own.

8 Daoist Immortals by Tani Bunchō: Tani Bunchō (1763–1841) was a Japanese literati painter and poet.

Ukiyo-e Woodblock Prints in the Edo Period

With the rise of popular culture in the Edo period, a style of woodblock prints called ukiyo-e became a major art form.

Learning Objectives

Describe the ukiyo-e woodblock prints of Edo Japan, and the social milieu they most famously depicted

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- With the rise of popular culture in the Edo period, a style of woodblock prints called ukiyo-e became a major art form.

- Its techniques were fine tuned to produce colorful prints of everything from daily news to schoolbooks. Subject matter ranged from Kabuki actors and the demimonde to courtesans and famous landscapes.

- Ukiyo-e prints began to be produced in the late 17th century, with Harunobu producing the first polychrome print in 1764.

- The dominant artistic figure of the 19th century was Hokusai’s contemporary, Hiroshige, a creator of romantic and somewhat sentimental landscape prints.

Key Terms

- Hiroshige: (1797–1858) A Japanese ukiyo-e artist and one of the last great artists in that tradition.

- ukiyo-e: A Japanese woodblock print or painting depicting everyday life.

- Katsushika Hokusai: (1760–1849) A Japanese artist famous for his woodblock print series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, which includes perhaps the most famous Japanese woodblock print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

Overview

With the rise of popular culture in the Edo period, a style of woodblock prints called ukiyo-e became a major art form. Its techniques were fine tuned to produce colorful prints of everything from daily news to schoolbooks. Subject matter ranged from Kabuki actors and courtesans to famous landscapes. By 1800, ukiyo-e flourished alongside Rinpa and literati painting.

The school of art best known in the West is that of the ukiyo-e paintings and woodblock prints of the demimonde—the world of the Kabuki theater and the brothel district. Ukiyo-e prints began to be produced in the late 17th century, and required a highly involved process that included a designer, engraver, printer, and publisher. Suzuki Harunobu produced the first polychrome (multicolor) print in 1764, and print designers of the next generation, including Torii Kiyonaga and Utamaro, created elegant and sometimes insightful depictions of courtesans.

Notable Artists

The best known work of ukiyo-e from the Edo period is the woodblock print series. Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (富 Fugaku Sanjūroku-kei, c. 1831), which includes the internationally recognized print The Great Wave off Kanagawa, was created during the 1820s by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849). Hokusai was influenced by such painters as Sesshu and other styles of Chinese painting. While Hokusai’s work prior to this series is certainly important, it was not until this series that he gained broad recognition. It was also The Great Wave print that initially received, and continues to receive, acclaim and popularity in the Western world.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa, Hokusai’s most famous print, the first in the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji: Although it is often used in tsunami literature, there is no reason to suspect that Hokusai intended it to be interpreted in that way. The waves in this work are sometimes mistakenly referred to as tsunami (津), but they are more accurately called okinami (沖), great off-shore waves.

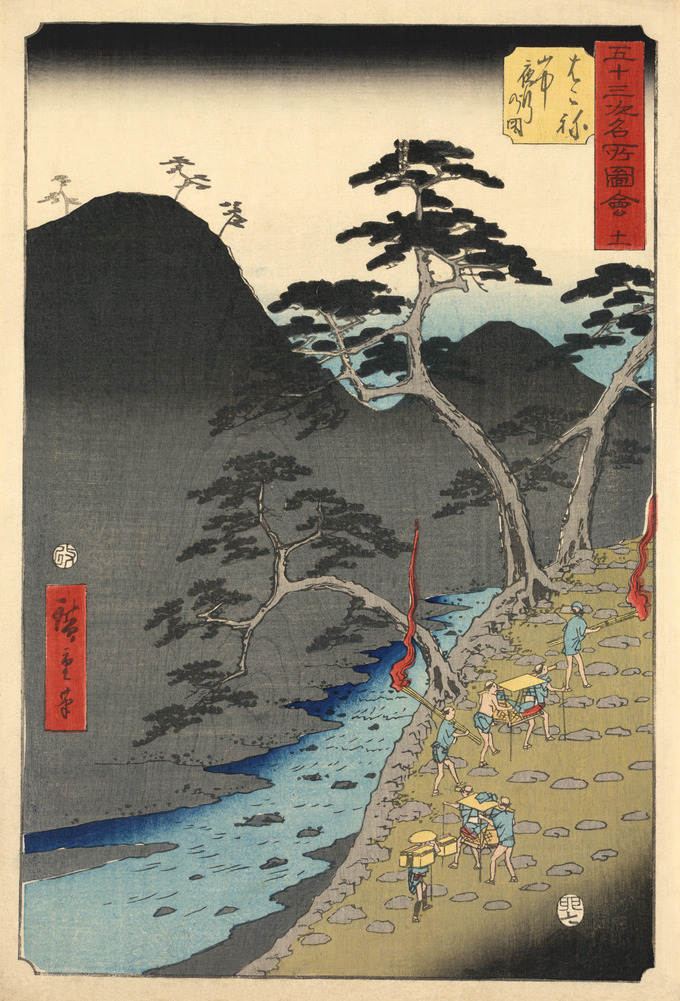

The dominant artistic figure of the 19th century was Hokusai’s contemporary, Hiroshige, a creator of romantic and somewhat sentimental landscape prints. The odd angles and shapes through which Hiroshige often viewed landscapes, with his emphasis on flat planes and strong linear outlines, had a profound impact on such Western artists as Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh. Through artworks held in Western museums, these same printmakers would later exert a powerful influence on the imagery and aesthetic approaches used by early Modernist poets like Ezra Pound and Richard Aldington.

Hiroshige’s Upright Tōkaidō depicts Hakone.: This print shows travelers and porters crossing a steep pass in the mountains at the Hakone station on the Tōkaidō Road.

Ukiyo-e was closely linked to the bunjinga, or literati, style of painting that emerged during the same period. Just as ukiyo-e artists chose to depict figures from life outside of the strictures of the Tokugawa shogunate, bunjinga artists turned to Chinese culture and based their paintings on those of Chinese scholar-painters. The exemplars of this style include Ike no Taiga, Yosa Buson, Tanomura Chikuden, and Yamamoto Baiitsu.

Zenga Painting in the Edo Period

Zenga is the Japanese term for the practice and art of Zen Buddhist painting and calligraphy, which developed during the Edo period.

Learning Objectives

Describe Zenga and its relation to Zen Buddhism

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Zenga is a style of Japanese ink-based calligraphy and painting.

- In many instances of Zenga, calligraphy and images are combined in the same piece; the calligraphy denotes a poem, or saying, that teaches some element of the path of Zen.

- The brush painting in Zenga is characteristically simple, bold, and abstract.

- In keeping with individual paths to enlightenment, nearly any subject matter can lend itself to Zenga; however the enso, sticks, and Mt. Fuji are the most common elements.

Key Terms

- Ensō: A Japanese word meaning “circle” and a concept strongly associated with Zen.

- Zenga: The Japanese term for the practice and art of Zen Buddhist painting and calligraphy.

Overview: Zenga Painting

Zenga is the Japanese term for the practice and art of Zen Buddhist painting and calligraphy; it is associated with the Japanese tea ceremony and also various martial arts. As a noun, Zenga is a style of Japanese calligraphy and painting done in ink. In many instances, both calligraphy and image will be merged within the same piece. The calligraphy denotes a poem or saying that teaches some element of the path of Zen; the brush painting is characteristically simple, bold, and abstract.

Example of Zen painting, Edo period: This Japanese scroll calligraphy of Bodhidharma reads: “Zen points directly to the human heart, see into your nature and become Buddha.” A man’s face is drawn under the calligraphy. It was created by Hakuin Ekaku (1685 to 1768).

Development of Zenga

Though Zen Buddhism had arrived in Japan at the end of the 12thcentury, Zenga art didn’t come into its own until the beginning of the Edo period in 1600. In keeping with individual paths to enlightenment, nearly any subject matter can and has lent itself to Zenga; however, the most common elements depicted were the ensō, sticks, and Mt. Fuji. In Zen Buddhism, an ensō is a circle that is hand-drawn in one or two uninhibited brushstrokes to express a moment when the mind is free to let the body create. The ensō symbolizes absolute enlightenment, strength, elegance, the universe, and mu (the void), and it is characterized by a minimalism born of Japanese aesthetics.

Ensō: Though nearly any subject matter can and has lent itself to Zenga paintings, one of the most common elements depicted was the ensō, a symbol of enlightenment.

Japanese aesthetics used in Zenga paintings were shaped by a set of ancient ideals that include wabi (transient and stark beauty), sabi (the beauty of natural patina and aging), and yūgen (profound grace and subtlety). These ideals, along with others, underpin much of Japanese cultural and aesthetic norms on what is considered tasteful or beautiful. Japanese aesthetics now encompass a variety of ideals; some of these are traditional, while others are modern and sometimes influenced by other cultures.

Crafts in the Edo Period

Traditional Japanese handicrafts associated with the Edo period include temari (a toy handball for children), doll-making, lacquerware, and weaving.

Learning Objectives

Name the traditional Japanese handicrafts developed during the Edo period

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The craft of making temari or handballs evolved into an art in the early Edo period. These balls were made from strips of old kimono silk and exquisitely embroidered with complex decorative stitching.

- Another craft that developed during the Edo period, when Japan was closed to most international trade, was elaborate doll-making; a market of wealthy individuals would pay for the most beautiful doll sets for their homes or as gifts.

- Japanese lacquerwork reached its peak in the 17th century, when lacquer was used to decorate a range of everyday items; the famous lacquerer Ogata Korin introduced a greater use of pewter and mother of pearl in lacquerware.

- Other important crafts during the Edo period include nishijin weaving, yuzen dying, and the production of wadokei or Japanese clocks.

Key Terms

- Hinamatsuri: A traditional Japanese doll festival held every year on March 3rd.

- Edo: Former name of Tokyo.

- temari: A folk craft born in ancient Japan from the desire to amuse and entertain children with a toy handball.

- gofun: A smooth, porcelain-like substance made from ground oyster shell.

- lacquer: A glossy, resinous material used as a surface coating.

Temari

Of the many and varied traditional handicrafts of Japan, the one closely associated with the Edo period (1600–1868) is the ancient craft of temari. Temari means “handball” in Japanese, and it is a folk craft born in ancient Japan from the desire to amuse and entertain children with a toy handball. Temari is said to have its origins from Kemari (football), brought to Japan from China about 1400 years ago. These balls were constructed from the remnants of old kimonos; pieces of silk fabric were wadded up to form a rough ball, and this preliminary ball was then further wrapped in additional strips of fabric. Temari-making gradually became an art, and the initially purely functional stitching assumed a decorative and detailed quality over the years, displaying intricate embroidery.

Temari-making grew as a pastime for noble women in the early part of the Edo period, with women of the aristocracy and upper class competing in creating increasingly more intricate and beautiful balls. Over the years and region by region, the women of Japan explored the craft and improved it. Noisemakers were added to the inside of the balls, Japanese designs mimicked the colors of nature, and the brilliant colors of kimono silk were used to stitch eye-catching patterns.

Temari: Temari balls are a folk art form that originated in China and was introduced to Japan around the 7th century A.D.

Doll-Making

Another craft that developed during the Edo period, while Japan was closed to most international trade, was doll-making. During this time, there was a market of wealthy individuals who would pay for the most beautiful doll sets for display in their homes or as valuable gifts. Sets of dolls came to include larger and more elaborate figures. The competitive trade was eventually regulated by the government, meaning that doll-makers could be arrested or banished for breaking laws restricting materials and heights.

Hina dolls are the dolls for Hinamatsuri, the doll festival held annually on March 3rd. They can be made of many materials, but the classic hina doll has a pyramidal body of elaborate, many-layered textiles stuffed with straw and/or wood blocks; carved wood hands (and in some cases feet) covered with gofun; a head of carved wood or molded wood compo covered with gofun, with set-in glass eyes (though before about 1850, the eyes were carved into the gofun and painted); and human or silk hair. A full set comprises at least 15 dolls representing specific characters, with many accessories (dogu); however, a basic set consists of a male-female pair, often referred to as the Emperor and Empress.

Hinamatsuri Hina Dolls, the Emperor with Two Handmaidens: Fine dollmaking developed during the Edo period (1603-1867).

Lacquerwork

Japanese lacquerwork reached its peak in the 17th century during the Edo period. Lacquer was used both for solely decorative objects as well as everyday items, such as combs, tables, bottles, headrests, small boxes, and writing cases. The most famous lacquerer-painter of the time was Ogata Korin, who was the first artist to use mother of pearl and pewter in larger quantities in lacquerware.

Lacquered Writing Box by Ogata Korin, ca. 1700.: This writing box made of black lacquered wood with gold, maki-e, abalone shells, silver, and corroded lead strip decorations dates from the 18th century and reflects the skill of the Edo painter and lacquerer Ogata Korin.

Other Crafts

Several techniques of Japanese weaving and dying also thrived during the Edo period. Nishijin weaving involved weaving many different types of colored yarn together to form decorative designs. In yuzen, or the paste-resist method of dying, designs were applied to textiles using stencils and rice paste, resulting in the imitation of aristocratic brocades, which were forbidden to commoners by laws of the Edo period.

Another Edo period craft that reflected contemporary Japan’s interest in electrical phenomena and mechanical sciences was the development of wadokei, or Japanese clockwatches. These were typically made of brass or iron in the lantern clock design and driven by weights.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Japanese art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_art%23Art_of_the_Edo_period. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Rimpa. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Rimpa. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Edo period. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Edo_period%23Popular_culture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Edo period. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Edo_period. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- lacquerware. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/lacquerware. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- swordsmith. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/swordsmith. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Fujin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Fujin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- White Prunus Korin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:White_Prunus_Korin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Kano school. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kano_school. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Kanu014d Motonobu. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kan%C5%8D_Motonobu. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Kano school. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kano%20school. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- literati. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/literati. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Fujin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Fujin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- White Prunus Korin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:White_Prunus_Korin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Shunkeizu. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Shunkeizu.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Japanese painting. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_painting%23Edo_period_.281603-1868.29. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bunjinga. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Bunjinga. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- sakoku. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/sakoku. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bunjinga. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Bunjinga. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Fujin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Fujin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- White Prunus Korin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:White_Prunus_Korin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Shunkeizu. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Shunkeizu.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 800px-%27Yearning_for_a_Pleasurable_Place%27_in_%27Mountains_of_the_Heart%27_by_Kameda_B%C3%B4sai%2C_1816.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kameda_B%C5%8Dsai#/media/File:%27Yearning_for_a_Pleasurable_Place%27_in_%27Mountains_of_the_Heart%27_by_Kameda_B%C3%B4sai,_1816.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 800px-8_daoist_immortals_by_Tani_Buncho.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tani_Bunch%C5%8D#/media/File:8_daoist_immortals_by_Tani_Buncho.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Ikeno Taiga 001. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ikeno_Taiga_001.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Great_Wave_off_Kanagawa. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Japanese art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_art%23Art_of_the_Edo_period. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Hokusai. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Hokusai. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Katsushika Hokusai. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Katsushika%20Hokusai. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- ukiyo-e. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/ukiyo-e. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Hiroshige. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiroshige. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Fujin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Fujin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- White Prunus Korin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:White_Prunus_Korin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Shunkeizu. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Shunkeizu.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 800px-%27Yearning_for_a_Pleasurable_Place%27_in_%27Mountains_of_the_Heart%27_by_Kameda_B%C3%B4sai%2C_1816.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kameda_B%C5%8Dsai#/media/File:%27Yearning_for_a_Pleasurable_Place%27_in_%27Mountains_of_the_Heart%27_by_Kameda_B%C3%B4sai,_1816.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 800px-8_daoist_immortals_by_Tani_Buncho.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tani_Bunch%C5%8D#/media/File:8_daoist_immortals_by_Tani_Buncho.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Ikeno Taiga 001. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ikeno_Taiga_001.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Hakone restored. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hakone_restored.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Great Wave off Kanagawa2. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Wave_off_Kanagawa2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Zenga. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Zenga. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Japanese aesthetics. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_aesthetics. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Enso. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Enso. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Zenga. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Zenga. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Fujin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Fujin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- White Prunus Korin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:White_Prunus_Korin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Shunkeizu. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Shunkeizu.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 800px-%27Yearning_for_a_Pleasurable_Place%27_in_%27Mountains_of_the_Heart%27_by_Kameda_B%C3%B4sai%2C_1816.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kameda_B%C5%8Dsai#/media/File:%27Yearning_for_a_Pleasurable_Place%27_in_%27Mountains_of_the_Heart%27_by_Kameda_B%C3%B4sai,_1816.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 800px-8_daoist_immortals_by_Tani_Buncho.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tani_Bunch%C5%8D#/media/File:8_daoist_immortals_by_Tani_Buncho.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Ikeno Taiga 001. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ikeno_Taiga_001.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Hakone restored. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hakone_restored.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Great Wave off Kanagawa2. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Wave_off_Kanagawa2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Bodhidarma. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bodhidarma.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Enso.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ens%C5%8D#/media/File:Enso.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- lacquer. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/lacquer. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Japanese traditional dolls. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_traditional_dolls%23The_Edo_period. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Edo period. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Edo_period. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Japanese crafts. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_crafts. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Edo. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Edo. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Hinamatsuri. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Hinamatsuri. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com//art-history/definition/temari--2. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Fujin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Fujin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- White Prunus Korin. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:White_Prunus_Korin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Shunkeizu. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Shunkeizu.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 800px-%27Yearning_for_a_Pleasurable_Place%27_in_%27Mountains_of_the_Heart%27_by_Kameda_B%C3%B4sai%2C_1816.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kameda_B%C5%8Dsai#/media/File:%27Yearning_for_a_Pleasurable_Place%27_in_%27Mountains_of_the_Heart%27_by_Kameda_B%C3%B4sai,_1816.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 800px-8_daoist_immortals_by_Tani_Buncho.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tani_Bunch%C5%8D#/media/File:8_daoist_immortals_by_Tani_Buncho.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Ikeno Taiga 001. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ikeno_Taiga_001.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Hakone restored. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hakone_restored.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Great Wave off Kanagawa2. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Wave_off_Kanagawa2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Bodhidarma. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bodhidarma.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Enso.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ens%C5%8D#/media/File:Enso.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Japanese_folk_art%3B_Temari%EF%BC%9B%E6%89%8B%E9%9E%A0.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Temari_(toy)#/media/File:Japanese_folk_art;_Temari%EF%BC%9B%E6%89%8B%E9%9E%A0.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Hinadolls. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hinadolls.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- WritingBox EightBridges OgataKorin. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WritingBox_EightBridges_OgataKorin.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright