20.6: Textiles of the Northern Renaissance

- Page ID

- 53068

Flemish Textiles of the Northern Renaissance

During the Burgundy period, Flanders became one of the richest parts of Europe, where magnificent tapestries where produced.

Learning Objectives

Examine the importance of tapestries in Flanders during the Burgundy period

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- By 1433, most of the Belgian and Luxembourgian territory, along with much of the rest of the Low Countries, became part of Burgundy under Philip the Good . When Mary of Burgundy, granddaughter of Philip the Good, married Maximilian I, the Low Countries became Habsburg territory.

- Flemish tapestries hung on the walls of castles throughout Europe. Some designs were influenced by the paintings of major Italian Renaissance artists such as Raphael, which were copied into textile form by Flemish artists who trained on the Italian peninsula.

- Millefleurs was a particularly popular style during the late 15th and early 16th centuries. This style features backgrounds filled with small, yet detailed, bouquets of flowers. The name literally translates from French as “a thousand flowers.”

- Among the most famous of Flemish tapestries is The Hunt of the Unicorn , often referred to as the Unicorn Tapestries: a series of seven tapestries dating from 1495–1505.

- The two major interpretations of many Flemish tapestries from the Renaissance hinge on both pagan and Christian symbolism .

Key Terms

- cartoon: A preparatory two-dimensional drawing of a finished artwork.

- slashing: A decorative technique that involved making small cuts on the outer fabric of a garment in order to reveal the inner garment or lining.

- Flanders: A subnational state in the north of federal Belgium, the institutional merger of a territorial region and the Dutch language “community” that also has/shares some authority in the capital region Brussels.

- unicorn: A mythical beast traditionally represented as having the legs of a buck, the body of a horse, the tail of a lion, and a single spiral horn on its head; a symbol of virginity.

- tapestries: A form of textile art, traditionally woven on a vertical loom, however it can also be woven on a floor loom as well. It is composed of two sets of interlaced threads, those running parallel to the length (called the warp) and those parallel to the width (called the weft); the warp threads are set up under tension on a loom, and the weft thread is passed back and forth across part or all of the warps.

The Evolution of Art and Industry

By 1433 most of the Belgian and Luxembourgian territory, along with much of the rest of the Low Countries, became part of Burgundy under Philip the Good. When Mary of Burgundy, granddaughter of Philip the Good, married Maximilian I, the Low Countries became Hapsburg territory. Their son, Philip I of Castile (Philip the Handsome), was the father of the later Charles V. The Holy Roman Empire was unified with Spain under the Hapsburg Dynasty after Charles V inherited several domains.

During the late Middle Ages—especially during the Burgundy period (the 15th and 16th centuries)— Flanders ‘s trading towns, particularly Ghent, Bruges, and Ypres, made it one of the richest and most urbanized parts of Europe, weaving the wool of neighboring lands into cloth for both domestic use and export. As a result, a very sophisticated culture developed, with impressive achievements in the arts and architecture, rivaling those of Northern Italy. Trade in the port of Bruges and the textile industry, mostly in Ghent, turned Flanders into the wealthiest part of Northern Europe at the end of the 15th century.

The Influence of Raphael in Brussels

The great period of Renaissance weaving in Brussels dates from the weaving entrusted by Pope Leo X (1475–1521) to a consortium of its studios of The Acts of the Apostles after cartoons by Raphael, between 1515 and 1519. The conventions of a monumental pictorial representation with the effects of perspective that would be expected of a fresco or other wall decoration were applied for the first time in these tapestries.

The prominent painter and tapestry designer Bernard van Orley (who trained in Italy) transmuted the Raphaelesque monumental figures to forge a new tapestry style that combined the Italian figural style and perspective rendition with the rich narrative and ornamental traditions of the Netherlands. Such elements can be found in his nine-part series called The Honors, of which the tapestry Fortuna is a notable example.

Millefleurs

Literally translating as “a thousand flowers,” the Millefleurs style refers to a background style of many different small flowers and plants, usually shown on a green ground , as though growing in grass. This style was most popular in late 15th- and early 16th century French and Flemish tapestry, with the best known examples in the series The Hunt of the Unicorn (see below). These are from what has been called the “classic” period, where each “bouquet” or plant is individually designed, improvised by the weavers as they worked, while later tapestries, probably mostly made in Brussels, usually have mirror images of plants on the right and left sides of the piece, suggesting a cartoon reused twice. Another classic example is The Triumph of Death (1510–20), in which the Fates represent death as they stand above the body of a fallen maiden. The background consists of rich vegetation expected in the millefleurs tradition.

The Hunt of the Unicorn

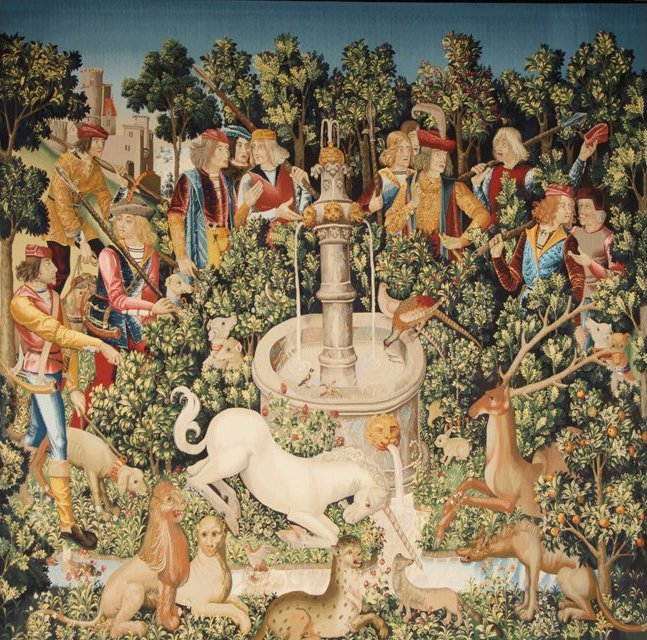

Flemish tapestries hung on the walls of castles throughout Europe. Among the most famous of Flemish tapestries is The Hunt of the Unicorn, often referred to as the Unicorn Tapestries. These constitute a series of seven tapestries dating from 1495–1505. The tapestries show a group of noblemen and hunters in pursuit of a unicorn. The tapestries were woven in wool, metallic threads, and silk. The vibrant colors still evident today were produced with three dye plants: weld (yellow), madder (red), and woad (blue). One tapestry, The Mystic Capture of the Unicorn, survives only in two fragments.

The second of the Unicorn Tapestries: The second of the seven tapestries, often called The Unicorn is Found.

Interpretive Traditions: Pagan and Christian

Much of the history of the Unicorn Tapestries is disputed, and there are many theories about their original purpose and meaning, including suggestions that the seven tapestries were not originally hung together. However, it seems likely that they were commissioned by Anne of Brittany to celebrate her marriage to the King of France Louis XII.

The two major interpretations of the tapestries hinge on pagan and Christian symbolism respectively. The pagan interpretation focuses on the medieval lore of beguiled lovers, whereas Christian writings interpret the unicorn and its death as the Passion of Christ. The unicorn has long been identified as a symbol of Christ by Christian writers, allowing the traditionally pagan symbolism of the unicorn to become acceptable within religious doctrine. The original myths surrounding The Hunt of the Unicorn refer to a beast with one horn that can only be tamed by a virgin. Subsequently, Christian scholars translated this into an allegory for Christ’s relationship with the Virgin Mary.

Ancient Graeco-Roman paganism lies in the interpretation of The Triumph of Death, with the Fates hailing from pre-Christian times. However, the tapestry may also align with the vanitas tradition, which began to emerge in the art of the Northern Renaissance and would become enormously popular with the elite classes of the Netherlands during the Baroque period. Vanitas images, whether as still-lifes or as women adoring their reflections, usually couple earthly (transient) concerns with a symbol or specter of death. No matter how concerned a woman might be with her beauty, death always lurks in the background and can strike at any moment, causing the viewer to focus on the preparedness of his or her soul for the afterlife.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Hunt of the Unicorn Tapestry 1. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Hunt_of_the_Unicorn_Tapestry_1.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 398px-Fates_tapestry.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2628868. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 640px-Honors_Tapestry_Fortuna.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18495274. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Brussels Tapestry. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Brussels_tapestry. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Renaissance in the Low Countries. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Renaissance_in_the_Low_Countries. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Millefleur. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Millefleur. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Unicorn. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/unicorn. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Devonshire Hunting Tapestries. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Devonshire_Hunting_Tapestries. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Flanders. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Flanders. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- History of Belgium. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Belgium. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Hunt of the Unicorn. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Hunt_of_the_Unicorn. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tapestries. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/tapestries. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike