15.3: Architecture of the Sub-Saharan Civilizations

- Page ID

- 53041

Architecture of Djenne

Djenné, once a thriving town in Mali, is known for its Great Mosque. This is the largest example of Sudanese-style mud-brick architecture.

Learning Objectives

Locate Djenné in time and place, and describe its Sudanese-style mud-brick architecture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- From the 11th to 13th centuries, Djenné was a leading commercial center in west Africa. After its decline during the rise of the Mali Empire, it continued to operate as an important trading post through the 17th century.

- The town, designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988, is famous for its distinctive Sudanese- style mud-brick architecture.

- The Great Mosque , originally built in the 13th or 14th century and then rebuilt in 1907, is the largest mud brick building in the world. It is considered by many architects the greatest achievement of the Sudano-Sahelian architectural style, with clear Islamic influence.

Key Terms

- pilaster: A rectangular column that projects partially from the wall to which it is attached; it gives the appearance of support, but is only for decoration.

- façade: The face of a building, especially the front.

- load-bearing: Architectural structural system in which the walls form the main source of support for the building.

- qibla: The direction that should be faced when a Muslim prays during the Call to Prayer.

- minaret: A tower outside a mosque from which a muezzin leads the Call to Prayer.

- parapet: Part of a perimeter that extends above the roof.

History

Djenné is a town and an urban commune in the inland Niger Delta region of central Mali. Between the 11th and 13th centuries, Djenné was a leading commercial center in West Africa. As a major terminal in the gold, salt, and slave trade of the trans-Saharan trade route, it flourished for several centuries. Much of the trans-Saharan trade in and out of Timbuktu passed through Djenné.

Djenné was also a chief center of Sudanese Islam in this period. Its Great Mosque was an important pillar of religious life. However, the rise of the Mali Empire in the 13th century contributed to the civilization’s steady decline, and its brief period of dominance ended when it was reduced to a tributary state. Between the 14th and 17th centuries, Djenné and Timbuktu were both important trading posts in a long-distance trade network. Both towns became centers of Islamic scholarship, and in the 17th century Djenné was a thriving center of learning.

The town is famous for its distinctive Sudanese-style mud-brick architecture, most notably the Great Mosque. To the south of the town is Djenné-Jéno, the site of one of the oldest-known towns in sub-Saharan Africa. Djenné, together with Djenné-Jéno and the Great Mosque, was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988.

Architecture

Nearly all of the buildings in the town consist of load-bearing walls made from sun-baked mud bricks coated with mud plaster. Because the walls are load-bearing, doors and windows must be small and few, often resulting in dark interiors. In Djenné, the mud-brick buildings need to be replastered with mud at least every other year. Even then, the annual rains can cause serious damage. Older buildings are often entirely rebuilt.

Traditional houses are two stories with flat roofs built around a small central courtyard. Constructed with imposing façades featuring pilaster-like buttresses , many have elaborate arrangements of pinnacles forming a parapet above the entrance door. The façades are decorated with bundles of rodier palm sticks called toron, that project away from the wall and serve as a type of scaffolding. Ceramic pipes extend from the roofline to protect the walls from rain water damage. Many houses built before 1900 are in the Toucouleur-style and have a massive covered porch set between two large buttresses. These houses generally have a single small window onto the street set above the entrance door.

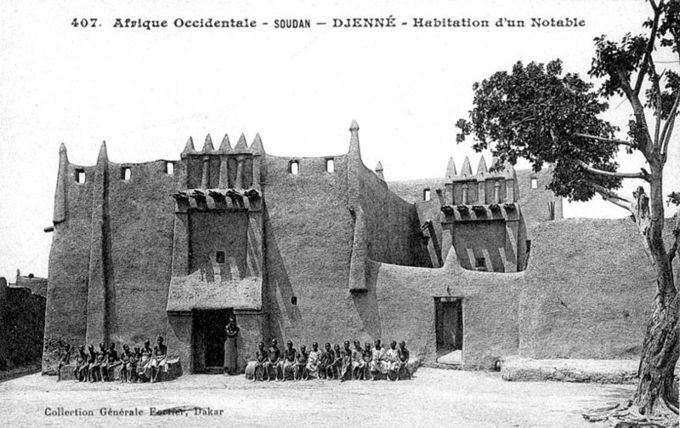

A house in Djenné: Many houses in Djenné are built with Toucouleur-style façades.

The Great Mosque

The rise of Islam witnessed a steady construction of mosques in the region. Sudano-Sahelian architecture reproduces the sacred architecture of Mecca in mud-brick and other local materials. Similar styles are evident in mosques in Ghana and Tunisia.

The Great Mosque of Djenné is the largest mud-brick or adobe building in the world, considered by many architects to be the greatest achievement of the Sudano-Sahelian architectural style with definite Islamic influences. As well as being the center of religious and community life, it is one of the most famous landmarks in Africa. The actual date of construction of the original mosque is unknown, but dates as early as 1200 and as late as 1330 have been suggested.

Falling into disrepair over the centuries, the French administration arranged for the original mosque to be rebuilt in 1907. The position of at least some of the outer walls appears follows those of the original mosque, but it is unclear as to whether the columns supporting the roof kept to the previous arrangement. What was almost certainly novel in the rebuilt mosque was the symmetric arrangement of three large towers in the qibla wall. There has been debate as to what extent the design of the rebuilt mosque was subject to French influence.

Great Mosque of Djenné: Originally built in the 13th or 14th century, the Great Mosque seen today was completed in 1907.

The qibla, which faces the direction of Mecca, is dominated by three large, box-like minarets jutting out from the main wall, each topped with an ostrich egg. The central minaret is approximately 48 feet tall. The eastern wall is roughly three feet thick and strengthened on the exterior by 18 buttresses. The corners are formed by rectangular buttresses topped by pinnacles.

The prayer hall, measuring about 85 by 164 feet, occupies the eastern half of the mosque behind the qibla wall. The mud-covered, rodier-palm roof is supported by nine interior walls running north-south and pierced by pointed arches that reach almost to the roof. In the prayer hall, each of the three towers in the qibla wall has a niche or mihrab . The imam conducts the prayers from the mihrab in the larger central tower. A narrow opening in the ceiling of the central mihrab connects with a small room situated above roof level in the tower. To the right of the mihrab in the central tower is a second niche, the pulpit or minbar, from which the imam preaches his Friday sermon.

Architecture of Aksun and Lalibela

Aksum and Lalibela were cities in northern Ethiopia that accomplished great feats of architecture.

Learning Objectives

Identify the famous rock-cut churches of Lalibela and the stelae, obelisk, and Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion of Aksum.

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Aksum was the original capital of the Kingdom of Aksum, a naval and trading power that ruled the region from about 400 BCE to the 10th century.

- The stelae were large stone towers that served as grave markers and reached up to 33 meters high.

- In 1937, the 24-meter tall, 1,700-year-old Obelisk of Aksum was discovered. Today it is widely regarded as one of the finest examples of engineering from the height of the Aksumite empire.

- The Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, believed to house the Ark of the Covenant, bears a design similar to that of Eastern Orthodox churches in Europe. Its most recent building, constructed in the 1950s, has a dome similar to the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

- Lalibela is a holy town most famous for its churches carved from the living rock, which play an important part in the history of rock-cut architecture . Its buildings, built in the 11th and 12th centuries, are considered symbolic representations of Jerusalem.

Key Terms

- Obelisk: A tall, square, tapered stone monolith topped with a pyramidal point, frequently used as a monument.

- rock-cut architecture: The creation of structures by excavating solid rock where it naturally occurs.

Aksum

Aksum (sometimes spelled Axum) is a city in northern Ethiopia that was the original capital of the Kingdom of Aksum. A naval and trading power, the kingdom ruled the region from about 400 BCE to the 10th century, reaching its height under King Ezana (baptized as Abreha) in the fourth century.

The stelae are the most identifiable part of the Aksumite legacy. These stone towers marked graves and were often engraved with a pattern or emblem denoting the person’s rank. The largest number are in the Northern Stelae Park, ranging to the grand size of the Great Stele (33 meters high, 2.35 meters deep, and 520 tons), which is believed to have fallen and broken during construction. The stelae have most of their mass above- ground but are stabilized by massive underground counterweights.

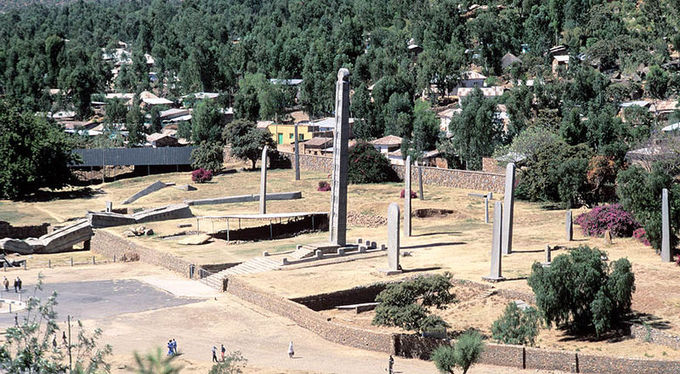

The Northern Stelae Park at the town of Axum, Ethiopia: The stelae in Northern Stelae Park range to 33 meters high.

The Obelisk of Aksum after its return to Ethiopia in 2005: The obelisk is an example of the stelae built by the Aksum kingdom.

Aksum is best known for the 1937 discovery of the 24-meter tall, 1,700-year-old Obelisk of Axum. Broken into five parts, it was found on the ground and shipped by Italian soldiers to Rome to be erected. The obelisk is widely regarded as one of the finest examples of engineering from the height of the Aksumite empire, and in 2005 it was finally returned to Aksum.

The Church of St. Mary of Zion, an Orthodox church built in 1665 and said to contain the Ark of the Covenant, is actually a reconstruction. The original church is believed to have been built during the reign of Ezana, the first Christian ruler of the Kingdom of Axum during the fourth century. It has been rebuilt several times since then. St. Mary of Zion was the traditional place where Ethiopian Emperors came to be crowned. In fact if an Emperor was not crowned at Axum or did not at least have his coronation ratified by a special service at St. Mary of Zion, he could not hold the official title.

Like many Eastern European churches, the Church of St. Mary of Zion is a centrally-planned structure with a dome serving as its focal point. In the 1950s the Emperor Haile Selassie built a new modern cathedral , open to both men and women, next to the old cathedral. Its dome bears a striking resemblance to the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey. The old church remains accessible only to men, as Mary, symbolized by the Ark of the Covenant allegedly resting in its chapel, is the only woman allowed within its compound.

Other points of interest include archaeological and ethnographic museums, the Ezana Stone monument documenting the conversion of King Ezana to Christianity, King Bazen’s megalith Tomb, Queen of Sheba’s Bath, the Ta’akha Maryam and Dungur palaces, the monasteries of Abba Pentalewon and Abba Liqanos, and the Lioness of Gobedra rock art.

Lalibela

Lalibela is a town in northern Ethiopia famous for its monolithic rock-cut churches. One of Ethiopia’s holiest cities second only to Aksum, Lalibela is a center of pilgrimage for much of the country. During the reign of Saint Gebre Mesqel Lalibela in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, the current town was known as Roha. St. Lalibela is said to have seen Jerusalem, then attempt to build a new Jerusalem as his capital in response to the capture of old Jerusalem by Muslims in 1187. As such, many features of the city have Biblical names—even the town’s river is known as the River Jordan. It remained the capital of Ethiopia from the late 12th century into the 13th century. The rural town is known around the world for its churches carved from living rock, which play an important part in the history of rock-cut architecture. There are thirteen churches, assembled in four groups:

- The Northern Group includes Biete Medhane Alem (home to the Lalibela Cross and believed to be the largest monolithic church in the world), Biete Maryam, Biete Golgotha (known for its arts and said to contain the tomb of King Lalibela), the Selassie Chapel, and the Tomb of Adam.

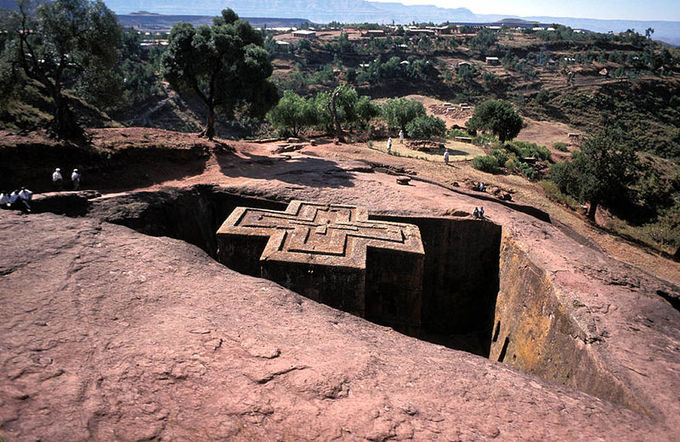

- The Western Group includes Biete Giyorgis, a cruciform structure, said to be the most finely executed and best-preserved church.

- The Eastern Group includes Biete Amanuel (possibly the former royal chapel), Biete Merkorios (possibly a former prison), Biete Abba Libanos, and Biete Gabriel-Rufael (possibly a former royal palace), linked to a holy bakery.

- The last group lies further afield. Located here are the monastery of Ashetan Maryam and the Yimrehane Kristos church (built in the eleventh century in the Aksumite fashion but within a cave).

Biete Giyorgis, the Church of St. George, in Lalibela, Ethiopia (top view): Biete Giyorgis is one of the finest examples of rock-cut architecture in Ethiopia.

Architecture of Great Zimbabwe

Perhaps the most famous site in southern Africa, Great Zimbabwe is a ruined city constructed by the Mwenemutapa.

Learning Objectives

Distinguish the features of the Hill Complex, the Greate Enclosure, and the Valley Complex of Great Zimbabwe.

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Small cattle-herding communities began to appear in the vicinity of what would become Great Zimbabwe from the fourth through seventh century CE. As the people began to exploit the nearby gold mines, their leaders became very rich and were able to form a centralized state.

- Capable of sustaining up to 18,000 people, Great Zimbabwe was built between 1100 and 1400 as a massive capital city and home to the king.

- Elaborate artifacts , including the famous soapstone Zimbabwe Birds, suggest that Great Zimbabwe was the hub of an extensive global trade network.

- By 1500, Great Zimbabwe was abandoned, either because of changes in the environment or changes in trade networks.

- Though European colonists long attempted to deny that Great Zimbabwe had been built by native Africans, it has become a major cultural landmark and source of pride in Africa.

Key Terms

- pastoralist: A person whose primary occupation is the raising of livestock.

Perhaps the most famous site in southern Africa, Great Zimbabwe is a ruined civilization constructed by the Mwenemutapa. A monumental city built of stone, it is one of the oldest and largest structures in southern Africa. Located about 150 miles from the modern Zimbabwean capital of Harare, Great Zimbabwe was the capital of a medieval kingdom that occupied the region on the eastern edge of Kalahari Desert.

Development of Great Zimbabwe

As there are no written records from the people who inhabited Great Zimbabwe, knowledge of the culture is dependent on archaeology. Small farming and iron-mining communities began to appear in the area between the fourth and seventh centuries CE. Most were cattle pastoralists , but the discovery of gold and new mining techniques contributed to a rise in trade with caravan merchants to the north. As local leaders became rich from trade, they grew in power and created the centralized city-state of Great Zimbabwe.

Monument Construction

Construction of the monument began in the 11th century and continued through the fourteenth century, spanning an area of 1,780 acres and covering a radius of 100 to 200 miles. At its peak, it could have housed up to 18,000 people. The load-bearing walls of its structures were built using granite with no mortar, evidence of highly skilled masonry. The ruins form three distinct architectural groups known as the Hill Complex (occupied from the ninth through 13th centuries), the Great Enclosure (occupied from the 13th through 15th centuries), and the Valley Complex (occupied from the 14th through 16th centuries).

One of the most prominent features of Great Zimbabwe was its walls, some of which reached 11 meters high and extended approximately 820 feet.

Close-up of Great Zimbabwe: Great Zimbabwe is most famous for its enormous walls, built without mortar.

There are stone structures linked by passageways and some parts of the site incorporate natural rock formations into the design, evident in at least one structure in the Hill Complex.

Notable features of the Hill Complex include the Eastern Enclosure, a high balcony enclosure overlooking the Eastern Enclosure, and a huge boulder in a shape similar to that of the Zimbabwe Bird. The Great Enclosure is composed of an inner wall encircling a series of structures, and a younger outer wall. The most important artifacts recovered from the monument are the eight Zimbabwe Birds. These were carved from soapstone on the tops of monoliths the height of a person. Slots in a platform in the Eastern Enclosure of the Hill Complex appear designed to hold the monoliths with the Zimbabwe birds, but archaeologists cannot be sure that this is where the birds rested.

Zimbabwe Bird: Copy of Zimbabwe Bird soapstone sculpture.

The Conical Tower was constructed between the two walls. The Valley Complex is divided into the Upper and Lower Valley Ruins, with different periods of occupation.

The Conical Tower: The Conical Tower is 18 feet (5.5 meters) in diameter and 30 feet (9.1 meters) high.

Valley Complex ruins: Ruins of the foundations demonstrate the same level of skill seen in the more intact walls elsewhere in Great Zimbabwe.

One theory suggests that the complexes were the work of successive kings. Perhaps the focus of power moved from the Hill Complex to the Great Enclosure in the 12th century, then to the Upper Valley, and finally to the Lower Valley in the early 16h century. A more structuralist interpretation holds that the different complexes had different functions. For example the Hill Complex was a temple, the Valley Complex was built for the citizens, and the Great Enclosure was used by the king.

Cultural Aspects of Great Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe shows a high degree of social stratification, characteristic for centralized states. For the elite, there seems to have been a great deal of wealth. Plentiful pottery, iron tools, copper and gold jewelry, elaborately worked ivory , bronze spearheads, gold beads and pendants, and soapstone sculptures have all been found at the site. Some of the artifacts, such as ceramics and glass vessels , appear to have come from Arabia, India, and even China, suggesting that Great Zimbabwe was a major trade center. Smaller stone settlements called zimbabwes can be found nearby. These are thought to be seats of authority for local governors acting under the king of Great Zimbabwe. These smaller settlements would have been supported by surrounding farmers.

Great Zimbabwe was abandoned by 1500, possibly due to land exhaustion, drought, famine , or a decline in trade. Zimbabwean culture would continue in Mutapa, centered on the city of Sofala. The site of Great Zimbabwe is considered a source of pride in the region, and the modern nation of Zimbabwe derived its name from the site. Nonetheless, when European colonizers first found the ruins in the late 19th century, most did not believe that the site could have been built by indigenous Africans. In fact, political pressure was put on historians and architects to deny its construction by black people until Zimbabwe’s independence in the 1960s.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Djenne Fortier 407. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Djenne_Fortier_407.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Great Mosque of Djennu00e9 1. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Mosque_of_Djenn%C3%A9_1.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Djennu00e9-Djenno. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Djenne-Djenno. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Qibla. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Qibla. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Parapet. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/parapet. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Fau00e7ade. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/facade. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- African Architecture. Provided by: Afropedea. Located at: http://www.afropedea.org/african-architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Great Mosque of Djennu00e9. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Mosque_of_Djenn%C3%A9. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Djennu00e9. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Djenne. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pilaster. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pilaster. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 640px-Bet_Abba_Libanos_(5499043130).jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22956378. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Church_Our_Lady_Mary_Zion_Axum_Ethio.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1408578. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bete Giyorgis Lalibela Ethiopia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bete_Giyorgis_Lalibela_Ethiopia.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Axum northern stelea park. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Axum_northern_stelea_park.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 640px-382-21.1.-Aksum-Maria_Zion.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24624987. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 372px-Bete_Giyorgis_03.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28203064. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Rome Stele. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Rome_Stele.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_Our_Lady_Mary_of_Zion. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Obelisk of Axum. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Obelisk_of_Axum. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Rock-Cut Architecture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock-cut_architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Kingdom of Aksum. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Aksum. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Lalibela. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Lalibela. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Axum. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Axum. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Obelisk. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Obelisk. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Great Zimbabwe (Donjon). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Zimbabwe_(Donjon).jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 262px-Zim-bird.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3475104. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Alloes-valley-great-zimbabwe.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8966650%20. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Eastern-enclosure-great-zimbabwe.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8966638%20. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Great_Zimbabwe_Ruins2.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3594362. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Great Zimbabwe Closeup. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Zimbabwe_Closeup.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Great Zimbabwe. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_zimbabwe. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Great Zimbabwe. Provided by: Saylor. Located at: http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/HIST101-7.2.1-GuptaDynasty-FINAL.pdf. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Saylor.org's Ancient Civilizations of the World/Mwenemutapa. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Saylor.org's_Ancient_Civilizations_of_the_World/Mwenemutapa. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pastoralist. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pastoralist. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike