9.3: Late Byzantine Art

- Page ID

- 53016

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Late Byzantine Art

Late Byzantine Art began after the sack of Constantinople in 1204 and continued until the fall of Byzantium in 1453.

Explain how art during the Late Byzantine period departed from the standards and styles seen in its early and middle periods

Key Points

- The French and Italian armies sacked Constantinople during the Fourth Crusades in 1204 and divided the Byzantium empire into smaller kingdoms. The Byzantines eventually re-conquered Constantinople in 1261 and the Byzantine Empire continued to reign until falling to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

- Art during the final centuries of the Byzantine Empire is known as Late Byzantine art and the styles and conventions of the Early and Middle Byzantine periods begin to change to reflect emerging dynamics and tastes.

- Mosaics and frescoes were still used for church decoration, although frescoed wall paintings became more popular. The change in favored medium also changed the types of imagery; wall paintings more heavily favor narrative scenes and cycles instead of standard single images.

- During this period landscapes and settings began to emerge in two-dimensional art. Furthermore, a new method of depicting the body, with softer modeling and shading was used. Robes and drapery are still schematically rendered, but the figures now have mass and tangible bodies.

Key Terms

- Ottoman: Of the Islamic empire of Turkey.

Late Byzantine Art

The period of Late Byzantium saw the decline of the Byzantine Empire during the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries. Although the capital city of Constantinople and the empire as a whole prospered as a connection between east and west traders, Byzantium continually dealt with threats from the Ottoman Turks to the east and the Latin Empire to the west.

During the Fourth Crusades, the Crusaders attacked Constantinople, took the city under siege in 1203, and eventually overcame its defenses to sack the city in 1204. Constantinople became the capital city of the Latin Empire, one of the new kingdoms of a divided Byzantium, until the Byzantines retook it in 1261.

Once more, Constantinople became a prosperous Byzantine city until falling to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The sack of Constantinople in 1204 marks the starting point of Late Byzantine Art, which lasted until the fifteenth century and spread beyond the borders of Byzantium.

Art during this period began to change from the standards and styles seen in the Early and Middle periods of Byzantium rule. A renewed interest in landscapes and earthly settings arose in mosaics, frescoes, and psalters . This development eventually led to the demise of the gold background.

The settings are often simple, perhaps a hill or a chair at first, and are often pastoral. Architecture began to be depicted more often, which renewed the use of perspective . At first buildings were rendered slightly skewed, but eventually artists refined the combination of material (mosaic and painting) with architecture and perspective .

Chora Church

Mosaic work was still popular in the Late Byzantine period, but frescoes and the depiction of narrative cycles began to increase in popularity to become the primary decoration in churches. This transition is seen in the Chora Church, which was initially decorated in mosaic, with the final wing decorated with wall paintings. The shift in media changed the subjects depicted.

Mosaics of single scenes and figures were replaced in favor of frescoed narrative cycles and biblical stories. The rendering of the figures also began to change. Artists now relied less on sharp, schematic folds and patterns and instead use softer, more subtle modeling and shading. While sharp folds in the drapery can still be found in images from this period, these folds are rendered in similar, not complimentary, colors and shades. Furthermore the bodies appear to have mass and weight. The figures no longer float or hover on their toes but stand on their feet. This allows for the addition of movement and energy in the painted figures and an overall increase of drama and emotion.

Pammakaristos Church

Although sculpture and column design are largely absent from discussions of Late Byzantine art, some notable fourteenth-century examples can be found in the Pammakaristos Church in Constantinople. Although the church was converted to a mosque in the fifteenth century, and all representations of humans and animals were either destroyed or covered, at least two fragments of a column capital depicting the busts of apostles in high relief survives in the collection.

While the heads of the men are somewhat large in proportion to their bodies, their bodies have assumed more naturalistic positions than their predecessors. They direct their gazes to either subtle or sharp angles. The two hands that are visible hold books, possibly the Gospels, to their chests. In sum, their poses anticipate the return to classicism that would define the Renaissance in the West.

The Chora Church in Constantinople

The Chora Church is decorated with iconic murals and mosaics from the fourteenth century that represent the Late Byzantine artistic styles.

Describe the ways in which the Chora Church in Constantinople represents Late Byzantine artistic styles

Key Points

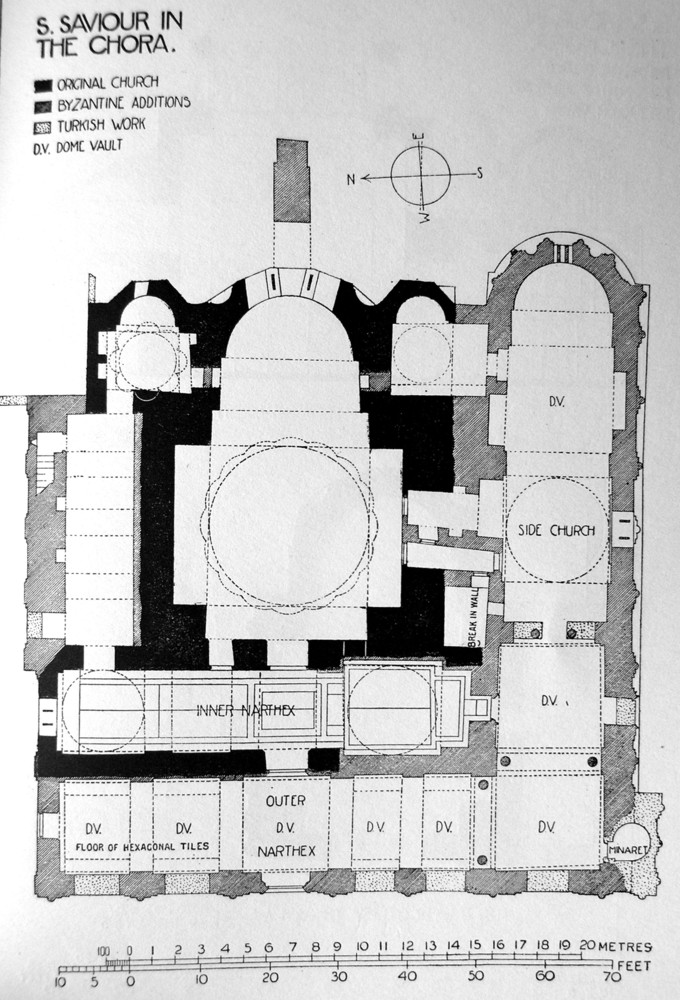

- The Chora Church’s architecture, mosaics , and frescoes are exceptional examples of Late Byzantine artistic developments and style . The church that stands today consists of two narthices, a parecclesion , and a mortuary chapel.

- The mosaics demonstrate the new weightiness and smoothness that is seen in Late Byzantine art. As is seen of the Koimesis Mosaic, the bodies are more modeled, delicately shaded, and have mass —the figures appear to stand on the ground instead of float.

- Frescoed wall painting is the primary means of decoration in the paracclesion. The program of images relate to Christ and the Virgin Mary by depicting scenes from their lives, their ancestors, and themes of salvation, which culminate in scenes from the Last Judgment.

- The apse fresco of the Anastasis depicts Christ redeeming Old Testament souls from Hell. The scene is full of energy and is centered on Christ who grabs the wrists of Adam and Eve. The figures are depicted with grace and a smooth modeling of mass and drapery.

- Throughout the mosaics and frescoes, Christ is depicted as a bearded (mature and wise) savior and ruler. This evolution from clean-shaven youth to bearded adult coincides with Christianity’s evolution from illegal religion to state religion.

Key Terms

- dado: The lower portion of an interior wall that is decorated differently from the upper portion.

- koimesis: Also known as the Dormition of the Virgin, this is a depiction of the Virgin Mary in her last sleep, at death, before ascending into Heaven.

- mandorla: An almond-shaped cloud or radiance that surrounds sacred figures, such as Christ or the Virgin Mary, in traditional Christian art.

- parecclesion: A side chapel found in Byzantine architecture.

- narthex: A western vestibule leading to the nave in some (especially Orthodox) Christian churches.

The Chora Church

The Chora Church’s full name is the Church of the Holy Savior in Chora. The church was first built in Constantinople during the early fifth century. Its name references its location outside the city’s fourth-century walls. Even when the walls were expanded in the early fifth century by Theodosius II, the church maintained its name.

Inside the church is a set of frescoes and mosaics that survived the church’s conversion into a mosque in the sixteenth century when its Christian imagery was plastered over. In 1948 the church became a museum after undergoing extensive restoration to uncover and restore its fourteenth-century decoration. It is now known as the Kariye Museum or Kariye Camii.

Architecture

The Chora Church that stands today is the result of its third stage of construction. This building and the interior decoration were completed between 1315 and 1321 under the Byzantine statesman Theodore Metochites. Metochites’ additions and reconstruction in the fourteenth century enlarged the ground plan from the original small, symmetrical church into a large, asymmetrical square that consists of three main areas:

- An inner and outer narthex or entrance hall.

- The naos or main chapel.

- The side chapel, known as the parecclesion. The parecclesion serves as a mortuary chapel and held eight tombs that were added after the area was initially decorated.

There are six domes in the church, three over the naos (one over the main space and two over smaller chapels), two in the inner narthex, and one in the side chapel. The domes are pumpkin-shaped, with concave bands radiating from their centers, and richly decorated with frescoes and mosaics that depict images of Christ and the Virgin at the center, with angels or ancestors surrounding them in the bands.

Mosaics

Mosaics extensively decorate the narthices of the Chora Church. The artists first decorated the church in the naos and then completed the work in the inner and outer narthices, which results in differences in the mosaics’ execution as the style progressed to show more liveliness and subtlety.

The surviving mosaics in the naos depict the Virgin and Child and the Dormition of the Virgin, a koimesis scene depicting the Virgin after death before she ascends to Heaven. This scene, located above the west door, depicts the Virgin in blue lying on a sarcophagus draped in purple and gold. Christ, in gold, stands behind the Virgin surrounded by a mandorla and holds an infant, representing the Virgin’s soul. The figures in the scene all have a certain weightiness that helps to ground them, adding an element of naturalism .

The mosaics found in the narthices of the Chora Church also depict scenes of the lives of the Virgin and Christ, while other scenes depict Old Testament stories that prefigure the Salvation. In the outer narthex, above the doorway to the inner narthex is a mosaic depicting Christ as the Pantocrator , the ruler or judge of all, in the center of a dome. The mosaic depicts a stern-faced Christ against a gold backdrop holding the gospels in one hand while gesturing with the other. An inscription in the mosaic reads, “Jesus Christ, Land of the Living.”

In another important scene above the entrance to the naos, Christ Enthroned is depicted receiving the donor of the church. The scene follows the Byzantine convention of depicting an architectural donation with an image of Christ in the center and the donor kneeling beside him, holding a model of his donation.

Here, Christ sits on a throne in a position similar to the Pantocrater, holding a book of gospels while his other hand gestures. The donor Theodore Metochites, wearing the clothing of his office, kneels on Christ’s right. He offers Christ a representation of the Chora Church in his hands. An inscription gives his titles.

Frescoes

The walls and ceilings of the parecclesion are decorated with scenes from the life of Christ and the Virgin, and themes of salvation befitting for a mortuary chapel. Like the mosaics, the scenes are painted in the upper levels of the building. The lower levels are reserved for painted images of saints and prophets and a decorative dado that mimics marble revetment .

The entirety of the parecclesion is covered in fresco scenes and painted images, creating an overwhelming sense of splendor and glory that ultimately brings the viewer to the final scenes of salvation and judgment.

Anastasis

The most important of these frescoes is the Anastasis, a representation of the Last Judgment, in the apse of the eastern bay . This image depicts Christ in Hell, saving the souls of the Old Testament. Christ stands in the center grasping the wrists of Adam and Eve, whom he raises from their sarcophagi. Saints, prophets, martyrs and other righteous souls, including John the Baptist, King David, and King Solomon, from the Old Testament stand on either side of Christ. Christ, standing over a bound Satan, wears a white robe and is framed by a white and light blue mandorla.

The image is the culmination of the parecclesion’s fresco cycle and one of the most impressive Late Byzantine paintings. Christ stands in an active, chiastic position. His arms reach out to Adam and Eve and his feet are positioned on uneven ground, providing the sensation of imbalance as he retrieves righteous souls.

The figures themselves are rendered in a softer, subtler mode. The harsh, jagged drapery has softened slightly with fluid and delineated folds. The expression of Christ and the others are dignified and stern. The Old Testament figures on either side gesture towards the scene, signaling the future of the faithful, as they wait for Christ to bring them into Heaven.

Changing Representations of Christ

The depictions of Christ in the Chora Church differ greatly from those of the third and fourth centuries. Recalling Early Christian art, Christ often appears clean shaven and youthful, sometimes cast as the Good Shepherd who tends and rescues his flock from danger. At a time when Christianity was illegal, Christians would have found such imagery of a protector reassuring.

By the fourteenth century, when Theodore Metochites funded the interior decoration, Christianity was no longer a fledgling faith; it was a state religion in which even the emperor recognized Christ as the ultimate authority. The images of Christ in the frescoes and mosaics of the Chora Church depict an authoritative, bearded man who occupies the role of both savior and judge. As an archetypal symbol of authority and wisdom through the ages, the beard would have been a logical choice for the face of the most supreme leader.

Icon Painting in Byzantine Russia

Andrei Rublev is considered the foremost fifteenth century Russian icon painter and the master behind the Old Testament Trinity.

Explain the evolution of Russian icon painting from the tenth century to the modern era

Key Points

- The tradition of Russian icon production began when the Kievian Rus’ converted to Orthodox Christianity in the tenth century. As time passed, the technique took on uniquely Russian attributes.

- Russian icon artists saw themselves as servants of God who transcribed the Gospels in visual form . Since they did not seek individual glory they did not sign their work, so the names of most Russian icon artists are unknown to Western scholars.

- The painted icons of Andrei Rublev, who worked in the fifteenth century, are considered to be the pinnacle of Russian icon painting, demonstrating the combination of Byzantine and Russian styles .

- The Old Testament Trinity that depicts the three angels hosted by Abraham and Sarah as described in Genesis 18, is an icon that is ascribed solely to Rublev’s hand. The icon is painted with brilliant colors and a delicate hand to depict subtle lines , modeling, and humanity in the scene.

- Exposure to Western styles and the dawn of the modern age changed the appearance of icons and the media in which they were produced: subject matter assumed a more realistic appearance by the seventeenth century and, by the early twentieth century, the mechanized printing press sparked the popularity of paper icons.

Key Terms

- tempera: A painting medium with either a casein or egg-yolk binder.

- prefiguration: A vague advance representation or suggestion of something.

Russian Icons

In 988 CE, the Slavic confederation known as Kievan Rus’ (a precursor to present-day Russia) adopted Orthodox Christianity as its official religion. Shortly thereafter, those living within its borders began producing icons. As a general rule, these icons strictly followed the traditional models and formulas of Byzantine art.

Nevertheless, as time passed, Russian artists widened the vocabulary of types and styles far beyond anything found elsewhere in the Orthodox world. Like Byzantine icons, Russian icons were usually small-scale paintings on wood. However, some icons produced for churches and monasteries were, at times, much larger. Russian artists also used alternative media, such as copper, for their work.

Russians sometimes speak of an icon as having been written because, in the Russian language, the same word means both to paint and to write. Icons are considered to be visual versions of the Gospels, and therefore, careful attention is paid to ensure that each Gospel is faithfully and accurately conveyed.

Because of these strict standards, artists saw themselves as God’s servants and did not strive for individual glory, as would become the norm in the West. For this reason, they did not sign their creations, and very few artists’ names are known to scholars outside of Russia. Andrei Rublev is one rare example.

Andrei Rublev

Russian icon painters flourished throughout the Byzantine period. Russian icons were known for their strict adhesion to Byzantine-style painting including the use of patterns, strong lines, and contrasting colors. Most Byzantine Russian icons were painted in egg tempera on wood panels. Gold leaf was often used for halos and background colors and bronze , silver, and tin were also used to embellish the icons.

The work of Andrei Rublev, a Russian icon painter in the fifteenth century, is considered to be the pinnacle of Byzantine Russian icon painting. Not much is known about his life. He was born in the 1360s and died in either 1427 or 1430.

What is known about Rublev comes from monastic chronicles, which account for his work as a painter and do not discuss his life. He is believed to have lived at the Trinity-St. Serguis Lavra, a monastery outside of Moscow in the town of Sergiyev Posad. Rublev is first recorded to have painted icons and frescos for the Cathedral of the Annunciation in Moscow in 1405.

He worked at the Cathedral of the Annunciation under Theopanes the Greek, a Byzantine master, who moved to Russia and is believed to have been Rublev’s teacher. Rublev also often worked with Daniil Cherni, another monastic artist. The two painted icons for the Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir in 1408 and the Church of the Trinity in the Trinity-St.Sergius Lavra monastery from 1425-1427.

The Old Testament Trinity

The icon known as the Old Testament Trinity (1411–1427) is the only work to be attributed solely to Rublev’s hand. It is considered to represent the brilliance of his work and the greatest achievement of Byzantine Russian icons. The egg tempera icon was made for the Church of the Trinity in the Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra and stands just less than five feet tall and is nearly four feet wide.

The icon depicts three angels around a table and is an illustration of Genesis 18, the Hospitality of Abraham, in which Abraham and his wife Sarah host three angels at their table. The scene focuses on the three angels and is full of symbolism that focuses on the mystery of the Holy Trinity and the prefiguration of salvation.

The image today is poorly preserved, but it demonstrates Rublev’s style and skill. The three angels sit around a table with a single chalice. The figures are delicately rendered. Their faces and hands are shaded to create volume , and their expressions are calm and serene. Each angel has a halo and wings, and holds a thin scepter.

Despite having nearly identical faces, their vividly painted garments help to distinguish them. Their garments are painted in rich, saturated colors. Each angel wears a robe in brilliant blue coupled with a second color including a orange, a deep red, and a green. The linearity of the robes highlights Byzantine methods of modeling that are based on the use of solid lines and complimentary colors to create contrasting folds and replicate the body’s mass and height.

While the figures appear weighty and naturalistic, the scenery and landscape around them are non-naturalistic. The table and chairs are painted in a skewed perspective and a small architectural detail in the upper left of the panel and a central tree create the basis of the setting.

Into the Modern Era

Until the seventeenth century, innovation was largely absent from icon production in Russia. When Roman Catholic and Protestant styles from Western Europe triggered new developments, the result was a split in the Russian Orthodox Church. The traditionalists—the persecuted Old Ritualists or Old Believers—continued the traditional stylization of icons, while the State Church modified its practice.

While some artists continued to produce figures in the traditional stylized manner, others opted for a mixture of Russian stylization and Western European realism very much like that of Catholic religious art of the time. The Westernization of Russian icons likely escalated under the reign of Tsar Peter the Great, whose cultural revolution brought Western values and the Enlightenment to Russia.

Tradition and the new style converge in an icon of Saint Nicolas and the Venerable Gerasimus of Boldino holding the much venerated Theotokos of Kazan. The Theotokos of Kazan was an icon of the highest stature within the Russian Orthodox Church. According to legend, it was acquired from Constantinople, lost in 1438, and miraculously recovered in pristine state in 1579. The icon was stolen and likely destroyed in 1904.

In the icon of Nicolas and Geasimus, the two saints, the icon, and the background are realistically rendered. The divine light source in the center causes naturalistic shadows to fall on the the hands of the two saints and the sides of their faces. Color and visual texture also mimic the natural world, while the tiles floor betrays a sense of realistic one-point perspective. Earth tones dominate the picture plane , pointing to possible Dutch Baroque (Protestant) influence.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, icon painting in Russia went into a great decline with the arrival of machine lithography on paper and tin. This new technology could produce icons in great quantity and much more cheaply than the workshops of painters. Today, Russian Orthodox worshippers purchase much larger numbers of paper icons than the more expensive painted panels.

Painting in the Late Byzantine Empire

As Late Byzantine painting became more naturalistic—bodies gained mass and figures portrayed humanity with emotion and movement—and these developments and traditions continued into the Post-Byzantine age.

Describe the form and content of icons and murals found in Late Byzantine painting and its immediate successors

Key Points

- Painters in the Late Byzantine period painted scenes with a new sense of naturalism by portraying figures with mass and naturalistic bodies under their clothing; drapery became a garment through which the body was rendered. Landscapes and settings were used more often, and figures were given increased movement and emotion to lend them an additional level of humanity.

- The Ohrid Icons are a series of icons produced in Constantinople that were later moved to Ohrid Macedonia. The Annunciation from one of the icons is a delicately painted scene filled with emotion and tension.

- The Crucifixion scene painted behind the altar of the Katholikon of the Monastery of the Virgin at Studenica is Serbia is another scene that depicts figures in the Byzantine style —they are infused with emotion and humanity, represented through their figure’s expressions and the sway of Christ’s body.

- During this time the iconostasis was fully developed and became a popular method of dividing the nave from the altar in Byzantine churches, especially in Russia. This screen was often large and covered in icons of saints and Christ in the general pattern of a Deesis .

- Even as the Byzantine Empire lost territory, its artistic traditions continued, most notably in the Cretan School. In this final phase of Byzantine art, figures and illusionistic space continued to assume greater degrees of naturalism, while the gold background remained in most icons.

Key Terms

- Katholikon: The major temple or church building of a monastery or diocese in an Eastern Orthodox Church.

- iconostasis: A wall of icons between the sanctuary and the nave in an Eastern Orthodox church.

- Deesis: An iconic representation, common in the Byzantine period, of Christ enthroned, Christ Pantocrator, surrounded by the Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist, often in supplication.

Late Byzantine Painting

The paintings in the Church of Christ in Chora are representative of the style of painting produced in the last centuries of the Byzantine Empire. Large murals were painted over expanses of architecture.

Many icons at this time were panels painted on both sides. Icons were painted this way since they were used in processions, and therefore seen from two directions. In churches, they were often displayed in special stands to allow for the viewing of both sides. Even after the Byzantine shrank and eventually fell, its artistic traditions continued in many former territories. The most famous example is the Cretan School.

Iconostasis

During the Late Byzantine period the iconostasis was fully developed. It was a screen or wall that stood in the nave, separating the space from the sanctuary and altar of the church. This wall was covered in icons and usually had three doors that allowed access into the sanctuary and viewing of the altar.

Icons were placed on the iconostasis following a general guideline that included the presence of a Deesis, Christ enthroned surrounded by John the Baptist and the Theotokos. Other icons included images of angels, saints, Old Testament prophets, the Apostles, and the patron saints of the church and city. The presence of the icons and the iconostasis was not to separate but to provide a bridge or a connection between the earthly and heavenly realms.

Ohrid Icons

The Ohrid Icons (early fourteenth century) were produced in Constantinople and were later moved to Ohrid in Macedonia. One icon depicts the Virgin Mary on one side and the Annunciation on the other side. The Annunciation portrays the Virgin Mary seated on a throne as the angel Gabriel approaches her to deliver the news of her conception of the son of God.

The background is typically Byzantine: gold leaf background that mimics the golden backgrounds of mosaics . The architecture is rendered in a later Byzantine style. The buildings are painted with an attempt at perspective that is more skewed than correct but that still provides a suggestion of space.

This was also seen in the Theotokos of the Hagia Sophia, but in this case the architecture provides more of a place setting, as in the landscape of the Lamentation from Nerezi. The figures themselves are rendered with Byzantine faces—small mouths and long, narrow noses. The faces, hands, and feet are carefully shaded and modeled.

The clothing is also follows the Byzantine style with dramatic, deep folds and a schematic patterning that renders the body underneath. The bodies, however, differ from their earlier Byzantine predecessors. They have weight and appear to exist underneath their clothing.

The scene also takes cues from Late Byzantine styles, since it is dramatically depicted. The Virgin’s rigid pose and single gesture signify her unease at the angel’s approach. Gabriel, meanwhile, appears to have just landed. He strides forward, with an arm outstretched. He places his weight completely on his left foot, while he prepares to plant his right foot on the ground .

We are witness to the moment of his arrival. The momentum of his arrival is further emphasized by the placement of his wings. One wing has settled down onto his back while the other reaches upwards to balance his flight. The movement and emotion in the scene can be related to the Anastasias scene of the Chora Church. Both images have a single, central figure full of motion that provides energy to the different scenes depicted.

Monastery of the Virgin at Studenica, Serbia

The Serbian Monastery of the Virgin was built in the twelfth century outside the city of Kraljevo. While the monastery’s churches do not appear from the outside to follow Byzantine architectural styles, the interior painting of the Katholikon, the Church of the Virgin, is painted in the Late Byzantine manner.

The Crucifixion, painted on the western wall overlooking the altar, represents the mastery of Serbian art and the development and spread of the Late Byzantine style from the center of Byzantium in Constantinople. The figures are less elongated than their earlier counterparts, and the background is painted in a brilliant blue with golden stars.

The central image of Christ on the cross is surrounded by mourners, including his mother. The figures in this calm scene have mass. While the Virgin Mary still appears to be a mass of robes, her drapery is more subtly rendered. The bodies of the other figures are more easily denoted by the modeling of their robes. The drapery is still reliant on deep folds, but the folds are no longer contorted and are less schematic. While less dramatic and more serene, there is an underlying emotion of sadness that is subtly depicted by the sway of Christ’s body.

The Cretan School

Over the course of the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries, the Byzantine Empire lost much of its territory. However, its artistic traditions continued for centuries in areas such as Crete.

Established, in the fifteenth century, the Cretan School is known for its distinct style of icon painting that was influenced by both Western and Eastern traditions. Even before the fall of Constantinople, the leading Byzantine artists were leaving the capital to settle in Crete. This migration continued in the following years and reached its peak after the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

The early icons produced by the Cretan School follow many of the earlier Byzantine traditions. Over the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as the styles of Italian and Northern Renaissance artists grew in popularity, the rendering of the human body and illusionistic space became increasingly realistic.

However, many icons retained the traditional gold backgrounds. The influence of the Renaissance, in which the notion of the artistic genius arose, can also be seen in the increasing attachment of artists’ names to their creations.

In the following examples by El Greco (1541–1614) and Emmanuel Tzanes (1610–1690), we can see the transition from the Late Byzantine style (in which the contours of the body were acknowledged beneath the drapery and attempts at realistic perspective were still evolving) to the Post-Byzantine style, which depicts a realistic recession of space and dynamic bodily poses.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pammakaristos_Church_fragments.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3867227. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Sant Salvador de Khora - Interior. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sant_Salvador_de_Khora_-_Interior.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- LatinEmpire2. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:LatinEmpire2.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Christ healing a paralitic in Caphernaum. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Christ_healing_a_paralitic_in_Caphernaum.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Byzantine Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chora Church. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Chora_Church. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pammakaristos Church. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Pammakaristos_Church. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Fourth Crusade. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Fourth_Crusade. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ottoman. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Ottoman. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Kariye camii innen2. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kariye_camii_innen2.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Kariye ic. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kariye_ic.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chora Church interior March 2008. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chora_Church_interior_March_2008.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- HSX Millingen 1912 fig 105. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:HSX_Millingen_1912_fig_105.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Genealogy of Jesus mosaic at Chora (1). Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Genealogy_of_Jesus_mosaic_at_Chora_(1).jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- HSX Koimetesis. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HSX_Koimetesis.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Dado. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/dado. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Beard. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Beard#Christianity. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Depiction of Jesus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Depiction_of_Jesus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chora Church. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Chora_Church. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mandorla. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/mandorla. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Koimesis. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/koimesis. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Narthex. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/narthex. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Parecclesion. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/parecclesion. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- GerBold_StNicolay.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17104237. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 410px-Feodorovskaya_u0441ast_copper_icon.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8359660. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Angelsatmamre-trinity-rublev-1410. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Angelsatmamre-trinity-rublev-1410.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Kievan Rus'. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kievan_Rus%27. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Our Lady of Kazan. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Our_Lady_of_Kazan. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Peter the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_the_Great. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Trinity (Andrei Rublev). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Trinity_(Andrei_Rublev). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Russian Icons. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_icons. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Old Testament Trinity. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Old_Testament_Trinity. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Andrei Rublev. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrei_Rublev. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tempera. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tempera. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Prefiguration. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/prefiguration. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ohrid annunciation icon. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ohrid_annunciation_icon.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Iconostasis in Moscow. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Iconostasis_in_Moscow.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Studenica Christi. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Studenica_Christi.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 384px-Tzanes_Emmanuel_-_St_Mark_the_Evangelist_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23718141. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 408px-Dormition_El_Greco.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17951018. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Emmanuel Tzanes. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Emmanuel_Tzanes. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Eastern Orthodox Church Architecture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Eastern_Orthodox_church_architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cretan School. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Cretan_School. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- El Greco. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Greco. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Byzantine Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- History of the Byzantine Empire. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Byzantine_Empire. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Studenica Monastery. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Studenica_monastery. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ohrid. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ohrid%23Medieval. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Iconostasis. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Iconostasis. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Deesis. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Deesis. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Iconostasis. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/iconostasis. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Katholikon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Katholikon. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike