4.6: Late Egyptian Art

- Page ID

- 52995

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Late Egyptian Art

The Late Period of Ancient Egypt (664–332 BCE) marked a maintenance of artistic tradition with subtle changes in the representation of the human form.

Describe art in the Late Period of Ancient Egypt

Key Points

- Though foreigners ruled Ancient Egypt during the Late Period , Egyptian culture was more prevalent than ever.

- Some sculptures of the Late Period maintain traditional techniques, while others feature more naturalistic attributes.

- One major contribution from the Late Period of ancient Egypt was the Brooklyn Papyrus . This was a medical papyrus with a collection of medical and magical remedies for victims of snakebites based on snake type or symptoms.

- The Thirtieth Dynasty took its artistic style from the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty.

Key Terms

- Late Period:The time of Ancient Egypt between the Third Intermediate Period until the conquest by Alexander the Great, from 664 BCE until 332 BCE; often regarded as the last gasp of the Egyptian culture.

The Late Period of ancient Egypt refers to the last flowering of native Egyptian rulers after the Third Intermediate Period from the Twenty-Sixth Saite Dynasty into Persian conquests, and ended with the conquest by Alexander the Great and establishment of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. It ran from 664 BC until 332 BCE. Though foreigners ruled the country at this time, Egyptian culture was more prevalent than ever. Libyans and Persians alternated rule with native Egyptians. Despite continued conventions in art, some notable changes in the human form did arise. The sculpture (pictured below) of the god Horus as a child (664–332 BCE) represents a combination of the typical stylized stance of Egyptian statuary with a fleshier body and pensive gesture of the right hand and arm.

The Late Period is often regarded as the last gasp of a once great culture, during which the power of Egypt steadily diminished.

Twenty-Sixth Dynasty

The Twenty-Sixth Dynasty, also known as the Saite Dynasty, reigned from 672–525 BCE. Canal construction from the Nile to the Red Sea began. According to Jeremiah, during this time many Jews came to Egypt, fleeing after the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem by the Babylonians (586 BCE). Jeremiah and other Jewish refugees arrived in Lower Egypt, notably in Migdol, Tahpanhes, and Memphis. Some refugees also settled at Elephantine and other settlements in Upper Egypt (Jeremiah 43 and 44). Jeremiah mentions pharaoh Apries (as Hophra, Jeremiah 44:30) whose reign came to a violent end in 570 BCE. This and other migrations during the Late Period likely contributed to some notable changes in art.

One major contribution from the Late Period of ancient Egypt was the Brooklyn Papyrus. This was a medical papyrus with a collection of medical and magical remedies for victims of snakebites based on snake type or symptoms.

Artwork during this time was representative of animal cults and animal mummies . The faience sculpture below shows the god Pataikos wearing a scarab beetle on his head, supporting two human-headed birds on his shoulders, holding a snake in each hand, and standing atop crocodiles. The style of this sculpture marks a departure from its predecessors in its fleshiness, positioning of its arms and hands, and slight smile.

Despite the changes that took place in the sculpture of Pataikos, artists continued to use the traditional canon of proportions. A sunken relief from a chapel at Karnak depicting Psamtik III, the final pharaoh of this dynasty, displays the maintenance of traditional conventions in representing the body.

Twenty-Seventh Dynasty

The First Achaemenid Period (525–404 BCE) marked the conquest of Egypt by the Persian Empire under Cambyses II. In May 525 BCE, Cambyses defeated Psamtik III in the Battle of Pelusium in the eastern Nile Delta. This basalt portrait bust (pictured below) of an unknown Egyptian dignitary from the period shows little change from convention in the representation of the human form. His necklace is typical of those made in the Achaemenid Period.

Twenty-Eighth through Thirtieth Dynasties

The Twenty-Eighth Dynasty consisted of a single king, Amyrtaeus, prince of Sais, who rebelled against the Persians and briefly re-established indigenous Egyptian rule. He left no monuments with his name. This dynasty reigned for six years, from 404–398 BCE. The Twenty-Ninth Dynasty ruled from Mendes, from 398–380 BCE.

The Thirtieth Dynasty took the art style from the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty. A series of three pharaohs ruled from 380 BCE until their final defeat in 343 BCE led to the reoccupation by the Persians. Art featuring Nectanebo II, the final ruler of this dynasty, appears largely in the traditional Egyptian style. Except for the small-scale greywacke (sandstone) statue in the Metropolitan Museum, which shows him standing before the image of Horus as a falcon, no other annotated portraits of the pharaoh are known.

A fragment of Nectanebo II’s portrait, with its partial smile and sagging chin, in the Museum of Fine Arts in Lyon, is slightly more naturalistic than previous representations of pharaohs.

Art and Architecture in the Kingdom of Kush

The Kingdom of Kush was an ancient African state whose art and architecture were inspired by Egyptian design, but were distinctly African.

Evaluate the influence of both Egyptian and African art on the art produced by the Kingdom of Kush

Key Points

- Kushite pharaohs built and restored many temples and monuments throughout the Nile Valley, and the construction of Kushite pyramids became widespread.

- The Kushites used relief sculpture to decorate the walls of palaces and pyramids. The cuts used were deeper and more strategic than Egyptian hieroglyphics . The reliefs mostly depict scenes from African daily life, animals, battle scenes, and kings.

- Kushite portrait sculpture adopts some Egyptian attributes but emphasizes distinctly indigenous features, such as wide faces and unique regalia, hairstyles, and symbolism.

- Pottery was an important Kushite craft and consisted mostly of pots and bowls that were shaped from clay and then painted in many different colors. Common decorative motifs included animals and geometric and plant-based patterns.

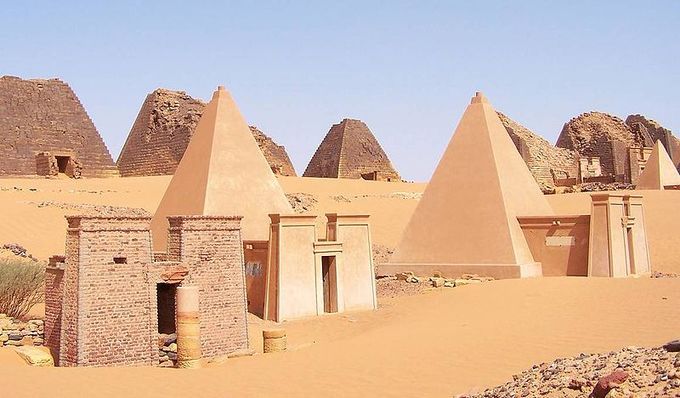

- The kings of Kush adopted the Egyptian architectural idea of building stone pyramids as funerary monuments. However, Kushite pyramids were built above the underground graves, whereas the Egyptian graves were inside the pyramid.

Key Terms

- relief:A type of artwork in which shapes or figures protrude from a flat background.

- pyramid:An ancient massive construction with a square or rectangular base and four triangular sides meeting in an apex, such as those built as tombs in Egypt or as bases for temples in Mesoamerica.

The Kingdom of Kush was an ancient African state situated on the confluences of the Blue Nile, White Nile, and River Atbara in what is now the Republic of Sudan.

Established after the Bronze Age collapse and the disintegration of the New Kingdom of Egypt, Kush was centered at Napata in modern day northern Sudan in its early phase, and then moved further south to Meroë in 591 BCE. After king Kashta invaded Egypt in the eighth century BCE, the Kushite kings ruled as Pharaohs of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty of Egypt for a century, until they were expelled by Psamtik I in 656 BCE. The reign of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty ushered in a renaissance period for ancient Egypt, and art and architecture emulating the styles of the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms flourished. Kushite pharaohs built and restored many temples and monuments throughout the Nile Valley, and the construction of Kushite pyramids became widespread. Some of these are still standing in modern Sudan.

Kushite Arts

The Kushite arts were inspired by the Egyptians, but were drastically African. Most remarkable among these was Kushite relief sculpture, which adorned the walls of palaces or pyramids. The cuts that are on the walls are deeper and more strategic than Egyptian hieroglyphics. There are many reliefs scattered across the land of Africa. They mostly depict scenes from African daily life and animals. Reliefs depicting battle scenes or kings are somewhat less common.

Statues of rulers and other royal individuals emphasize the foreign, non-Egyptian origin of their subjects. The Head of a Kushite Ruler (c. 716-702 BCE), identified by some scholars as King Shabaqa, depicts a man with a typically round Kushite face. Although his eyes bear resemblance to those of Egyptian individuals in art, his hairstyle and regalia are distinctly non-Egyptian. The front of his headband once featured two cobras. While Egyptian pharaohs commonly wore a single cobra on their headgear, the double-cobra motif was unique to the Kushite culture .

Pottery was another important Kushite craft and consisted mostly of pots and bowls that were shaped from clay and then painted in many different colors. Most pottery was initially made for the wealthy, but later on, many commoners also began using pottery in their households. While decoration usually took the form of painted designs, some types of pottery also had stamped designs. Common motifs included geometric and plant-based patterns. The finest pottery was decorated with paintings of animals, such as giraffes, antelopes, frogs, crocodiles, snakes, and a variety of birds.

Kushite Architecture

The kings of Kush adopted the Egyptian architectural idea of building pyramids as funerary monuments. However, Kushite pyramids were built above the underground graves, whereas the Egyptian graves were inside the pyramid. The kings’ tombs were lodged under large pyramids made of stone. For a short time, the Kushite kings were mummified. Ordinary citizens were buried in much smaller pyramids. The most famous examples of Kushite pyramids are located in their capital Meroë. There are three cemeteries in Meroë; the north and south cemeteries are royal cemeteries and house the pyramids of kings and queens, whereas the west cemetery is a purely non-royal site.

Egyptian Art After Alexander the Great

Hellenistic art, richly diverse in subject matter and in stylistic development, characterized culture after Alexander the Great.

Describe the major events of the Ptolemaic Kingdom and the key characteristics of Hellenistic art

Key Points

- The Ptolemaic Kingdom (332–30 BCE) in and around Egypt began following Alexander the Great ‘s conquest in 332 BCE and ended with the death of Cleopatra VII and the Roman conquest in 30 BCE.

- Hellenistic art is richly diverse in subject matter and in stylistic development. It was created during an age characterized by a strong sense of history. For the first time, there were museums and great libraries, such as those at Alexandria and Pergamon.

- Prominent in Hellenistic art are representations of Dionysos, the god of wine and legendary conqueror of the East, as well as those of Hermes, the god of commerce. In strikingly tender depictions, Eros, the Greek personification of love, is portrayed as a young child.

- Hellenistic civilization continued to thrive even after Rome annexed Egypt after the battle of Actium and did not decline until the Islamic conquests.

- Portraits of male rulers grew increasingly naturalistic, while those of female rulers and non-elites remained stylized .

Key Terms

- Hellenic:Referring to the ancient Greek world.

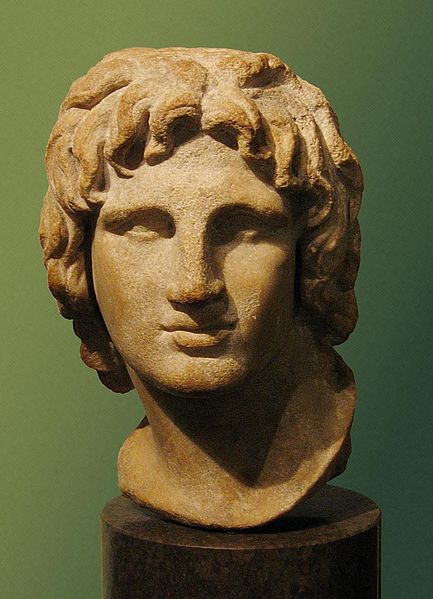

- Alexander the Great:Alexander the Great was a king of Macedon, a state in northern ancient Greece. Born in Pella in 356 BCE, Alexander was tutored by Aristotle until the age of 16. By the age of 30, he had created one of the largest empires of the ancient world, stretching from the Ionian Sea to the Himalayas. He was undefeated in battle and is considered one of history’s most successful commanders.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (332–30 BCE) in and around Egypt began following Alexander the Great’s conquest in 332 BCE and ended with the death of Cleopatra VII and the Roman conquest in 30 BCE. It was founded when Ptolemy I Soter declared himself Pharaoh of Egypt, creating a powerful Hellenistic state stretching from southern Syria to Cyrene and south to Nubia. Alexandria became the capital city and a center of Greek culture and trade.

Hellenistic Art

Hellenistic art is richly diverse in subject matter and in stylistic development. It was created during an age characterized by a strong sense of history. For the first time, there were museums and great libraries, such as those at Alexandria and Pergamon. Hellenistic artists copied and adapted earlier styles , and also made great innovations. Representations of Greek gods took on new forms . The popular image of a nude Aphrodite, for example, reflects the increased secularization of traditional religion. Also prominent in Hellenistic art are representations of Dionysos, the god of wine and legendary conqueror of the East, as well as those of Hermes, the god of commerce. In strikingly tender depictions, Eros, the Greek personification of love, is portrayed as a young child.

Encouraged by the many pharaohs, Greek colonists set up the trading post of Naucratis, which became an important link between the Greek world and Egypt’s grain. As Egypt came under foreign domination and decline, the pharaohs depended on the Greeks as mercenaries and even advisers. When the Persians took over Egypt, Naucratis remained an important Greek port, and the colonists were used as mercenaries by both the rebel Egyptian princes and the Persian kings, who later gave them land grants, spreading the Greek culture into the valley of the Nile . When Alexander the Great arrived, he established Alexandria on the site of the Persian fort of Rhakortis. Following Alexander’s death, control passed into the hands of the Lagid (Ptolemaic) dynasty ; they built Greek cities across their empire and gave land grants across Egypt to the veterans of their many military conflicts. Hellenistic civilization continued to thrive even after Rome annexed Egypt after the battle of Actium and did not decline until the Islamic conquests.

Nile Mosaic of Palestrina (c. 100 BCE)

One significant change in Ptolemaic art is the sudden re-appearance of women, who had been absent since about the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty. This phenomenon was likely due, in part, to the increasing importance of women as rulers and co-regents, as in the case of the series of Cleopatras. Although women were present in artwork, they were shown less realistically than men in the this era, as is evident in a portrait of a Ptolemaic queen (possibly Cleopatra VII) from the first century BCE. Unlike its Classical and Hellenistic counterparts elsewhere in the Hellenic world, this sculpture bears a more stylized appearance.

Among male rulers, portraiture assumed a more naturalistic appearance, even when the sitter was pictured in traditional Egyptian regalia, as in a relief of Ptolemy IV Philopator (r. 221–204 BCE), who wears the traditional pharaonic crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. However, even with this Greek influence on art, the notion of the individual portrait still had not supplanted Egyptian artistic norms among non-elites during the Ptolemaic Dynasty.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 640px-Roll,_664_-_332_B.C.E._Brooklyn_Papyrus_47.218.48a-f.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33288717. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 480px-Head_of_Nectanebo_II-MBA_Lyon_H1701-IMG_0204.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15270671. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 360px-Karnak_Psammetique_III.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3577107. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Statue_dignitary_27th_dynasty_Florence.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36455543. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 215px-HorusAndNectaneboII_MetropolitanMuseum.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1745992. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 320px-Horus_as_a_child-MBA_Lyon_H1704-IMG_0155.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15185913. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 344px-Figure_of_Pataikos,_664-30_B.C.E._Faience,_glazed,37.949E.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33295232. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Nectanebo II. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Nectanebo_II. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Statue: Dignitary 27th Dynasty. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Statue_dignitary_27th_dynasty_Florence.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Late Period of Ancient Egypt. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Late_Period_of_ancient_Egypt. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Brooklyn Papyrus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Brooklyn_Papyrus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Twenty-Seventh Dynasty of Egypt. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Twenty-seventh_Dynasty_of_Egypt. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Twenty-Sixth Dynasty of Egypt. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Twenty-sixth_dynasty_of_Egypt. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Psamtik III. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Psamtik_III. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Definition of Late Period. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com/art-history/definition/late-period. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Art of Ancient Egypt. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_ancient_Egypt. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 488px-Head_of_a_Kushite_Ruler,_ca._716-702_B.C.E..jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36343528. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Africa in 400 BC. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Africa_in_400_BC.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sudan Meroe Pyramids 30sep2005 2. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sudan_Meroe_Pyramids_30sep2005_2.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Nubian Pyramids. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Nubian_pyramids. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- African Kingdoms. Provided by: bmssancientcivilizations Wikispace. Located at: bmssancientcivilizations.wikispaces.com/African+Kingdoms. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Kingdom of Kush. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Kush. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- relief. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/relief. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- pyramid. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pyramid. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 370px-Ring_with_engraved_portrait_of_Ptolemy_VI_Philometor_(3rdu20132nd_century_BCE)_-_2009.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6185029. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 360px-Ptolemaic_Queen_(Cleopatra_VII-),_50-30_B.C.E.,_71.12.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34005509. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 640px-0_Eros_dormiente_-_Musei_Capitolini_-_MC1157 (1).jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26244388%20. License: CC BY: Attribution

- NileMosaicOfPalestrina. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:NileMosaicOfPalestrina.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- AlexanderTheGreat Bust. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:AlexanderTheGreat_Bust.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Nile mosaic of Palestrina. Provided by: Wikipedia . Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Nile_mosaic_of_Palestrina. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Greco-Roman. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Greco-Roman. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ptolemaic Kingdom. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemaic_Kingdom%23Art_during_the_Ptolemies. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Alexander the Great. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Alexander_the_Great. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike