17.4: Post-war Design and the Domestication of Modernism

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

In another sector of American culture, far removed from the edginess of the 1950s avant-garde, were designers and architects who combined a new sophistication and confidence with international influences, using new manufacturing techniques and materials. In the decades after World War II, the redesign of the everyday living environment emerged as a central undertaking for this generation of designers. Good design was no longer merely for the elite.

Beauty, convenience, and comfort were now to be within the reach of ordinary Americans, including returning veterans and their young families. As with streamlining-the style of the years between the wars-the movement for good design profited from the presence of European talent. Two furniture companies in particular-Herman Miller and Knoll Associates-worked closely with modernist designers such as the Americans Charles Eames (1907-78) and George Nelson (1908-86), Finnish architect Alvar Aalto (1898-1976), and emigre German architect Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969), to produce and distribute innovative furniture. In collaboration with museums and department stores, post-war designers marketed modernism to the masses. The good design movement of the post-war years turned away from streamlined forms suggesting speed-driven frictionless modernity, preferring instead organic shapes emphasizing comfort and functionality Biomorphic design, evoking nature and the body, helped consumers feel at ease in the increasingly artificial environments of air travel, and corporate and suburban spaces. In architecture and product design, organic forms, soft contours, and molded spaces vied with the impersonal appeal of stark "International Style"

Museums and the Marketing of "Good Design"

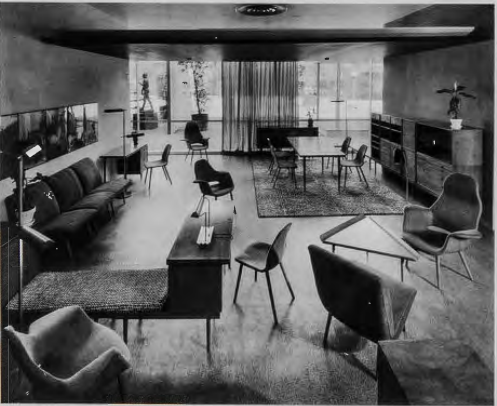

Continuing a marketing trend established in the 1920s, American museums took the lead in educating consumers about good design. In such exhibits as the Museum of Modern Art's "Useful Objects," which offered products ranging in price from 25 cents to 25 dollars in 1946, and its "Good Design" program between 1950 and 1954 (fig. 17.25), or the Walker Art Center's Everyday Art Gallery, in Minneapolis, featuring bowls, ceramics, radios, and household appliances, fine arts institutions around the nation encouraged high-quality industrial and product design.

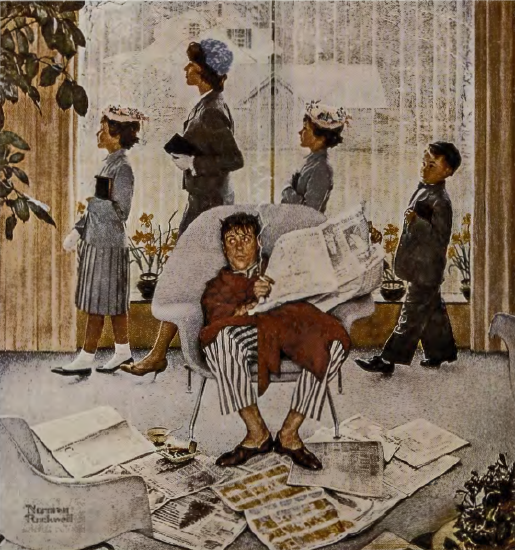

The museum expanded its educational mission to the middle class, and from the fine arts to domestic living. As American industry shifted from wartime to peacetime production, museums teamed up with industries, designers, and retailers to "domesticate" modernism: Norman Rockwell's young husband escapes church by reading the paper in Eero Saarinen's Womb Chair, as the newest in mid-century modern is comfortably accommodated in suburban domesticity (fig. 17.26). As the corporate "hidden persuaders" gained a hold over consumers through the allure of advertising, advocates of good design saw their mission as instructing middle-class families about how to live. Often they adopted the same strategies as corporate business. The Museum of Modern Art used the techniques associated with mass marketing- consumer surveys, TV and magazine advertising, and public education through panel discussions-to make good design widely accessible. As with so many other aspects of Cold War culture, design was recruited in the cause of a morally fortified nation, unified around core principles: good taste made good citizens.

Communities of Taste

LIKE OTHER CONSUMER PRODUCTS, one's choice of everyday design came to denote a great deal about one's educational level, living preferences, and social networks. In the 1950s post-war tract developments of single-family homes with lawns and small children, the furniture of choice was stuffed, padded, and upholstered. More sophisticated consumers (those who may have also listened to jazz and traveled to Europe) chose Scandinavian modern. Scandinavian proved to be an acceptable middle-of-the-road form of modernist design for many: well made, with accommodatingly soft contours and the comforting familiarity of wood, Scandinavian furniture introduced a new level of unornamented simplicity and harmonious lines that combined machine manufacture with handcrafted forms. Textiles, ceramics, and glassware expanded on the Scandinavian aesthetic.

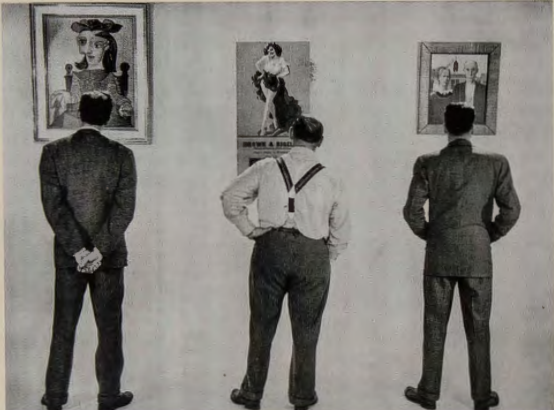

Taste in the mid-century United States was precisely calibrated to one's social class, as this staged photograph suggests (fig. 17.27). The social stratification of "high brows," "middle brows," and "low brows" was given material expression through product design. The ostensibly classless nature of American society paradoxically produced class anxieties: the more one insisted on the absence of social distinctions based on equal access to opportunity, the more they came in through the back door of design and material life. Apart from the big divide between modern and traditional, the modern itself was a rather complicated affair. One observer identified ten different types of modern design in American everyday living, among them "Unrelenting Modern" (Bauhaus); "Nostalgic Modern" (streamlined); Floradora Modern (glitzy glamorous Hollywood, identified with the work of the well-known designer Elsie de Wolfe, 1865?-1950); and Jukebox Modern (selfexplanatory).22 Bridging these stylistic distinctions was a common concern with style as an indicator of one's particular social identity, self-image, and placement within American life.

Charles and Ray Eames

From airport waiting areas, to university classrooms, to family dens, the designs of Charles and Ray (1912-88) Eames have enjoyed a deep presence in our everyday visual environment throughout the second half of the twentieth century. As a husband and wife team their careers wove together the best aspects of European modernist designa commitment to affordable, functional, and aesthetically sensitive objects for everyday living- with an enthusiasm for new materials (plastic, fiberglass, molded plywood, and polyester resin), and an inventive approach to mass production that characterized post-war America (fig. 17.28). Buoyed by confidence in the applications of science and industry to solving quality-of-life issues for middle-class Americans, the Eameses offered a vital example of how to humanize environments .shaped by mass production and standardization.

Their melding of European and American approaches also integrated two streams of modern design: the rationalist machine aesthetic associated with standardized production, and the biomorphic organicism of soft yielding shapes. Driven by the emerging science of ergonomics, these designs considered how to accommodate human bodies to machined objects. One of the Eameses' most ubiquitous chair designs, done in collaboration with architect Eero Saarinen (1910-61), consisted of a single molded plastic seat that could be combined with other parts in a wide variety of permutations. Varying a few basic elements-materials (molded plastic, wire mesh, and padded upholstery), color ( orange, green, blue, black, and yellow), and base (pedestal, rocker, swivel, and wire strut)- the Eameses furnished a reliable standardized form with customized features, in a manner similar to earlier inventive American designers like Hunzinger (see fig. 10.27). Their exuberant personal style, friendly designs, and marketing sophistication made modernism accessible to millions of middle-class Americans.

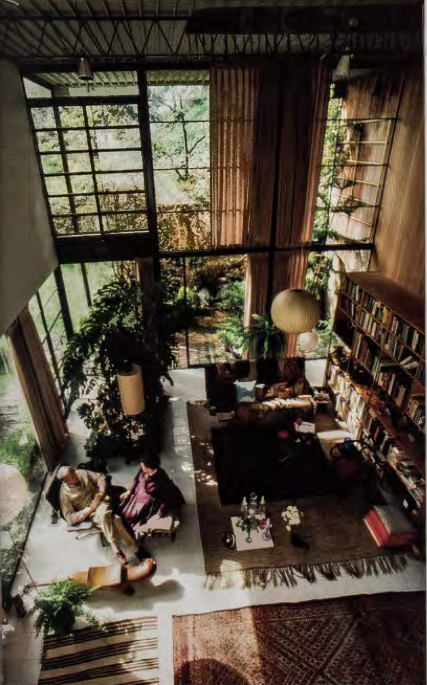

During wartime, they developed leg splints and litters for the Navy out of molded laminated bentwood, in which industrial methods were combined with a technique for bending thin layers of wood that had its counterpart in bentwood containers made in Native Alaskan and Northwest Coast cultures (see fig. 7.30). After the war, they perfected their methods to mass-produce the distinctive plywood "Eames Chair." As one admirer wrote, they produced "organic abstractions in which esthetics and science meet on the plane of utility."23 Design in their hands spoke to practicality and to the emotional requirements for meaningful connection with the world of things. The interior of the home Charles and Ray Eames designed for themselves in Pacific Palisades, California (fig. 17.29) shows the relaxed combination of modern furnishings (their own 1956 lounge chair and ottoman of molded plywood and leather) and ethnic artifacts-masks, textiles, stools, and carvings. The fluid relationship of indoor to outdoor space exploited the qualities of the southern California environment.

Women were among the major figures of post-war American design. Ray Eames, though overshadowed by her husband Charles, has recently been restored to her proper place as an innovator. Florence Knoll (b. 1917) established one of the leading design firms of these years, Knoll International, with her husband, and went on to transform the look of the American corporate office with sleek upholstered chairs and sofas that combined European modernist influences with American comfort. Annie Albers (1899-1994) and Eva Zeisel (b. 1906) made important contributions to textile and ceramic design. Yet hierarchies remained. Architecture was a difficult profession for women to enter in the 1950s; they instead directed their talents into textiles, ceramics, and other "minor" arts.

Machines to Bodies: Biomorphic Design

Machine Age design between the two world wars took its inspiration from the precise, interchangeable, repetitive forms of machine production; design in the years following World War II increasingly emphasized wholeness, integrity, and organic unity. This turn to the "biomorphic" crossed the design arts to take in architecture, offering an alternative to the sleek glass and steel modernism that increasingly defined corporate culture.24 Artists such as the sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904-88) (fig. 17.30) and architects such as Saarinen also turned to furniture design. Saarinen's Womb Chair (see fig. 17.26), manufactured by Knoll, employed a fiberglass shell over bent steel rods. As with other biomorphic shapes in Saarinen's furniture, the compound curves (curves, that is, in multiple planes) and laplike welcome of the Womb Chair carried a ready appeal for consumers who admired the combination of up-to-date industrial materials with yielding forms and reassuring references to the human body.

Like streamlining in the 1930s, post-war biomorphic design developed into a style independent of function. It was applied to everything from kitchenware to casinos, from textiles to ceramics, glassware, and furniture, and from architectural interiors to the kidney-shaped pool in the backyard. It reached across media and across the economic and taste spectrum. It brought the night-time fantasies and whimsical psychic landscapes of the Surrealists-in particular the biomorphic shapes of Jean Arp (1886-1966), Paul Klee (1879-1940), and Max Ernst (1891-1976)-into the light of an American suburban morning. Designer Eva Zeisel compared the melting forms of 1940s tables, containers, and other household objects to the disturbingly fluid shapes of Surrealist painter Salvador Dali, suggesting metamorphosis, mutation, and transformation.25 Like the organic abstraction of the early twentieth century, biomorphism represented a return to nature as a realm distinct from the technological, a flight from the hard-edged, the machined, and the geometric. It returned the post-war consumer back to the curving, welcoming shapes of the maternal body

Unlike that earlier organic abstraction, however, the "vital forms" of these decades were shaped by a knowledge of nuclear science and atomic radiation. Embedded in these fluid shapes were echoes of another kind of transformation: genetic mutation. Fantasies of mutating life forms found expression in popular film, venting widely felt anxieties about the impact of radiation. Invoking a life energy running through matter, biomorphic objects threatened to exceed boundaries and defy containment to seep, like the amoeboid body snatchers and monsters of B-grade horror films, into the cells of wholesome Americans. Like the atom, the life force expressed in biomorphic design served widely varied cultural fantasies and anxieties.

The International Style: Architecture as Icon

In 1932 the Museum of Modern Art opened an influential exhibition of modernist architecture curated by Henry Russell Hitchcock (1903- 87), a historian, and a young Harvard-trained architectural enthusiast, Philip Johnson (1906-2005). Called "The International Style: Architecture since 1922," the survey included some fifteen different Western nations, and some forty architects. Hitchcock and Johnson's selection revealed a unifying style: "a modern style as original, as consistent, and as logical, ... as any in the past."26 The 1932 exhibition codified a series of developments in architecture of the 1920s. These included an emphasis on volume over mass: the walls, freed from their load-bearing function by the steel skeleton or cage, could become membranes containing space. Asymmetry and modularity, the expression of standardized parts or building units, now replaced classical and static symmetry. Applied decoration was banished; natural colors were preferred to applied colors. Any form of whimsy or personal idiosyncrasy was decried.

In the decades between the wars, International Style modernism developed away from the tight prescriptions of the style as it was put on view at the Museum of Modern Art. Ironically, the principles codified by the 1932 exhibition at the Modern would become a "style" self-consciously emulated rather than emerging out of experimentation and innovation. The Modern Movement would come to include independents such as Frank Lloyd Wright, who did not conform to the tenets of the International Style but who, nonetheless, influenced such key figures as Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius. Other tendencies emerged in modern American architecture in the years following 1932, including regional influences, local non-industrial materials, and a more sculptural treatment of space. The term "International Style," however, would remain in circulation, though primarily in reference to the steel and transparent glass curtain-wall monoliths of corporations. During the 1950s, the "International Style" acquired the aura of prestige associated with wealth and sophisticated taste.

MIES VAN DER ROHE AND THE CORPORATE BUILDING. The highly rationalized glass and steel language of the transparent skyscraper, originating in unbuilt visionary schemes by Mies, Le Corbusier, and others in Europe in the 1920s, found a particularly hospitable home in the corporate America of the 1950s. The architect most responsible for the transatlantic migration of the glass skyscraper in the 1940s and 1950s was the emigre German Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. After working in Berlin in the 1910s, Mies had designed a handful of steel-framed, glass curtain-walled buildings in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1937 Mies moved to the United States following the closing of the Bauhaus, where he taught and served as director from 1930 to 1933. After World War II, and benefiting from the presence of former Bauhaus designers such as Mies, Marcel Breuer (1902- 81), and Walter Gropius (1883-1969 ), modernist design principles would increasingly replace the dominance of Beaux Arts pedagogy in schools of architecture around the country, most notably in Chicago, when Mies became director of the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1938; and at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard, where Gropius became Chair of Architecture in 1937. The corporate patronage of the leading prewar figures of European architectural Modernism was perceived by many as a sign of American cultural ascendancy after World War II.

The classic expression of the glass and steel office building of the 1950s was Mies's Seagram Building (fig. 17.31). Towering over Park Avenue, a dark weighty monolith, the Seagram became the very image of corporate culture: sternly disciplined, self-contained, aloof yet powerful. A skin of bronze I-beam mullions and tinted bronze glass surrounds a steel cage; within, the column grid opens space for multiple and flexible uses. Yet a closer engagement with the building reveals a different side.

Architectural historian William Jordy has analyzed the humanism of the Seagram. Its 3:5 ratio of depth to width gives it a reassuring bulk; its colored glass and bronze facade works against a sense of weightless transparency often associated with the style. Thirty-eight stories high, the Seagram is set back 90 feet from the street, giving the pedestrian an opportunity to take its measure before entering. Within, the meticulous detailing of every aspect of the interior, from lighting to plumbing fixtures and door knobs, elevator cabs, and graphic design elements, embodies the architect's rigorous attention to every part of the building. Classically proportioned, thoughtfully sited, and sensitively detailed, the Seagram belies charges that the International Style was impersonal and bureaucratic. However, its rationalism, no longer serving the utopian ideals of architectural modernism in the 1920s, now appeared to many as the architectural arm of corporate business.

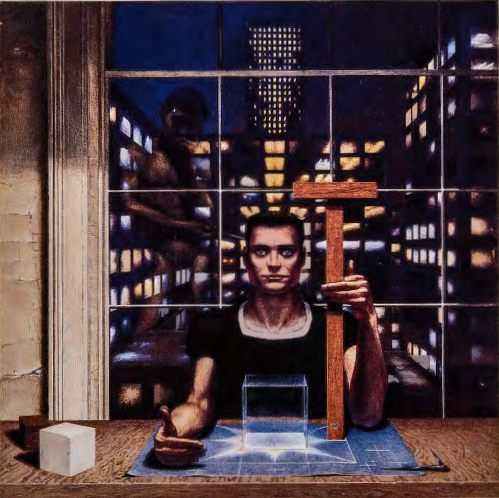

Paul Cadmus's The Architect (fig. 17.32) is a disturbing tribute to this latter vision of the International Style. Holding the T-square, the square-jawed young architect sits before a transparent cube, his head located at the vanishing point in a perspectival space formed by a series of gridded planes and buildings. A phantom-like muse hovers behind him, the only exception to the rigidly right-angled world of the painting. Cadmus captures the static Platonic perfection of the glass monolith. But he also captures the critique launched against it by those who felt it served an arid and inhuman vision of urban modernity. Architectural historian William Curtis sums up this current of thought: "The 'Modern Project' achieved something of a popular victory on American soil, but in the process lost something of its soul."27

Organic Design: Architecture as Sculpture

For architects converted to the rigors of European modernism, the seductive curves and swelling ovoids of biomorphic design were highly suspect. They were associated with the feminine realm brought to excess in the 1950s infatuation with the breast, and associated with male dependence on the mother. Biomorphic design also carried the unwanted allure of advertising and commerce-like the streamlined, it addressed consumer desire rather than abstract reason. Appropriate for the realms of post-war pleasure-resort hotels, lounges and bars, department stores, and suburban backyards-the biomorphic was considered a concession to popular taste, and banished from the corporate boardroom or from such spaces of elite culture as the Museum of Modern Art. Nevertheless, two exceptional projects by two exceptional architects realized the sculptural possibilities inherent in cast-in-place concrete on a monumental scale.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT'S GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM. In the tradition of organic design descending from Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) remained true to his organic principles until his death; indeed, his commitment to archetypal form found extraordinary expression in the final building of his career, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (figs. 17.33 and 17.34). It took sixteen years to complete, years filled with doubts about the museum's viability as an exhibition space, as well as with outright ridicule. In 1956, the editors of the New York Times described the effect of the new building as that of "an oversized and indigestible hot cross bun."

Wright violated a number of received ideas in his design. The core of the building was an inverted spiral, a form he had used for earlier designs never built. The Guggenheim combined modern poured concrete with ancient forms like the ziggurat (stepped pyramid) of the ancient Near East. Like so many other aspects of the 1950s which brought together Western physics and Eastern philosophies, the Guggenheim expressed the new reality of energized space, as Wright put it himself, "space instead of matter," drawing an idea from the Chinese philosopher Lao Tze.28 But this ziggurat with its ancient associations seemed ill-suited to the grid of Manhattan avenues and streets. Inside, it is expressed as an inclined ramp that circles upward, around and around toward the light-filled oculus. Primary exhibition space is located along the exterior curving walls, a design that provoked protests from artists and critics alike. Most agreed that however bold and effective Wright's building was as form, it did not serve its function particularly well. Despite the controversy, in 1959, the year it opened (and the year of Wright's death), five hundred leading architects ranked it in a survey as the eighteenth most important building in the United States.

Even if Wright's design did not serve the exhibition needs of the Guggenheim, it served the museum in other ways. By the 1950s, Wright was a figure of international renown, acknowledged as the nation's greatest living architect. And the Guggenheim, having begun as an elite private collection, was established as a powerful and memorable presence in Manhattan, drawing crowds into its dramatic spiraling interior. The instant notoriety of the new Guggenheim accounted, according to a survey undertaken soon after its opening, for 40 percent of the visitors who walked through its doors. Despite the conservative nature of Wright's ideas-individualistic in a time of expanding corporate presence in American life; inward-turning during a period when urban life was ever more shaped by mass media and consumerism-he nonetheless anticipated with uncanny accuracy what the public wanted in a museum of modern art. Modern art would come to be associated as much with the spectacle of movement, light, and space animated by people, as it would with the contemplation of the art on its walls. Through his signature building, Wright succeeded in creating an audience for modernism never dreamed of even by its most ardent proselytizers.

EERO SAARINEN'S TWA TERMINAL. For his design for a new TWA terminal at New York City's Idlewild (now JFK) Airport (figs. 17.35 and 17.36), Bero Saarinen (1910--61) chose an elegantly stylized organic form of cast concrete lobes that billowed out in bold cantilevers, resembling a great bird in flight. Saarinen had begun his career studying sculpture, a sensibility dramatically apparent in his manner of designing the TWA Terminal. In these years the reigning traditions of architectural design derived from either the Paris Beaux Arts or from the German Bauhaus. In both traditions, space was conceived in two-dimensional representations: drawings on paper relaying the site plan of the building, the elevations of its fac;ades, cross-sections of its inner workings, and details of its constituent elements. Orthogonal plans readily worked for right-angled buildings, or for forms that curved in only two dimensions (a curved wall for instance). Saarinen, on the other hand, developed his sculptural forms through models that realized the three-dimensional curving forms of his design. Only after this model phase did his office produce drawings-nearly six hundred-that translated the three-dimensional model back into two dimensions. Saarinen's working method and sculptural conception were altogether new.

The TWA Terminal was a resounding popular success, giving to the new industry of commercial flight-just entering its jet phase-a glamorous and dynamic stage through which passengers flowed in arcing movements that mirrored its sinuous spaces. The TWA Terminal served both those who used the building and its corporate patrons, offering to the first visual drama with subliminal appeal, and to the second a "signature" building markedly different from the glass cubicles of other airlines. Saarinen's design pushed the structural limits of cast concrete, implying technical mastery and aspiration, while creating a serene space where travelers could pause amidst the dynamic energies of modern travel.