16.1: The Depression and the Narrative Impulse

- Page ID

- 172920

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)People tell stories to remind themselves of where they came from, and to secure their identities against the pressures of everyday survival. The narratives of the 1930s, whether texts or images, persistently situated the period in a broader historical landscape. Narrative, however, can act in a variety of ways, creating reassuring fables or fully engaging the complexities of experience. Common to all forms of narrative art in the 1930s-from history to legend to contemporary social conflict, and from mural painting to photography- is a focus on the human figure as the carrier of political, social, and mythic meanings.

The belief that the arts played a major part in shaping communal life supported the narrative impulse. Whether in the post office murals done under the aegis of the federal Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture (1938- 43), or in the fostering of community art centers, the 1930s turned away from the elitist basis of earlier art. The idea of aesthetics as remote from the concerns of everyday life- " art for art's sake"-gave way to a different model of "art as experience," in the words of John Dewey (1859-1952), the influential American philosopher and author of a book by that title, published in 1934. Dewey argued that the "aesthetic" was "part of the significant life of an organized community," rather than something separate from it. Art was, in his terms, an intensification of life. He opposed ''the museum conception of art" which failed to satisfy the aesthetic impulses of ordinary people.2 The modernist conception of art as "self-expression," the particular badge of an individual creator, gave way to a reassertion of art's role in the symbolic life of people tied to a particular place. Dewey's ideal of "art as experience" dispensed with the hierarchies between fine and practical arts, and between the high arts and popular media. A Pueblo pot, a mural in a public building, a quilt, a harvest dance-each gave aesthetic form to the social relations that linked members of a community to one another and to a place.

One of the great artistic accomplishments in the 1930s was the development of large-scale public mural art. Before the 1930s, murals and sculpture in public places were supposed to depict values outside politics, as well as above the growing social, class, and ethnic divisions within urban populations. In truth, however, such "public" art always served specific political interests. At the turn of the century, murals usually spoke from a position of greater economic and social power to those with less power.

The relationship between the artist and the public shifted between the turn-of-the-century years and the 1930s. Artists began to give voice to the experiences of ordinary men and women, as workers, as family members, as citizens. Artists increasingly thought of themselves as workers, sharing concerns about wages and working conditions with other laborers. The effect was to politicize artmaking, moving art out of the museum and the gallery and into the lives of ordinary people, as they visited hospitals, post offices, libraries, or other public buildings. With its democratic premise of "art for all," 1930s public art aspired to visual readability and clarity of meaning, in the process enlarging the limited story-telling capabilities of easel art.

Taylorization and the Assembly Line "Speed-up"

IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY, Frederick Winslow Taylor's time-and-motion studies of workers, together with Henry Ford's assembly-line methods, revolutionized mass production. Taylorization and Fordism, the bywords of this new system, restructured the workplace, and transformed the nature of human labor. Taylorization aimed to reengineer the human body itself by forcing it to conform to the "laws" of efficiency, eliminating all wasted motion. Ford's assembly-line production in turn required the worker to repeat the same task over and over, on the same set of parts, through the innovation of the conveyor belt and the craneway, which brought the parts to the worker. The resulting regimentation of labor forced the body of the worker to conform to the demands of the production process.

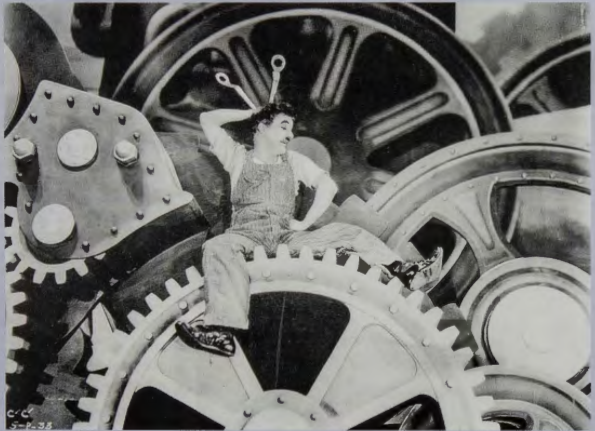

The "speed-up," which forced workers to increase production by speeding up the conveyor belt that set the pace of their labor, contributed not only to the growing volume of goods available to American consumers, but also prompted increased labor militancy between the wars. In the 1936 film Modern Times, the Tramp, played by Charlie Chaplin, first submits to, and then resists, the discipline of the assembly line. The famous opening factory sequence reveals the ironclad necessities of production and profit that threaten quite literally to consume the worker. The Tramp reclaims his quirky irregularity of movement only following a physical breakdown, which begins when he throws himself into the guts of the machine (fig. 16.1). Chaplin brilliantly dramatizes the fear that mechanization would crush the subtle inner rhythms of the human body and spirit.

Mexican Muralists and Their Influence on Public Art

Of critical importance to the scale and ambition of American mural art during the 1930s was the precedent of mural painting in Mexico, inspired by the revolution (1910-17). After overthrowing the corrupt regime of Porfirio Diaz, reformers sought to redistribute the wealth of the financiers and landowners, who had ruled during decades of modernization, to the broad base of newly empowered peasants and urban workers. Beginning in the 1920s, the newly installed reform government decorated public buildings in Mexico City and elsewhere, in an effort to create new national narratives that would glorify the goals of the revolution. Mexico's mural movement looked to the country's indigenous history to ground an emergent national identity independent of European culture. The Mexican mural program was an important example for George Biddle, an American artist who first proposed it as a model of patronage to President Roosevelt as a means of promoting his New Deal program of national recovery. A national art had the power to mobilize collective energies toward a more just society, and its emotional reach would compel public consent for a reengineered social order, while at the same time revitalizing American art by linking it to national life and ideals.

Hundreds of American artists traveled to Mexico to view these works firsthand . They also learned from Mexican muralists who came to execute works in the United States. Jose Clemente Orozco (1893- 1949), David Siqueiros (1896-1974), and Diego Rivera (1886- 1957), known collectively as "Los Tres Grandes" (The Three Great Ones), won major commissions in the United States beginning in the late 1920s. Ironically, while inspiring a socially engaged art of the people, much of the Mexican muralists' work in the United States was commissioned by wealthy capitalists.

America's infatuation with things Mexican reached across the political spectrum. Rivera and his colleagues were emulated by American artists on the left who embraced their vision of a revolutionary society. Artists and writers of all political stripes longed for intact folk and Indian cultures such as they saw in Mexico. A wealthy capitalist such as John D. Rockefeller, who held major investments in oil, had other reasons for pursuing Rivera and his colleagues. Responding to the threat of Mexican nationalization of industry, the Rockefellers courted favor with the new government by patronizing its favorite artists. They sponsored exhibitions of Mexican art at the Museum of Modern Art and elsewhere. Nelson Rockefeller (son of John D. and an heir to the Standard Oil fortune) commissioned Rivera to paint a mural in the lobby of the RCA Building in Rockefeller Center. However, when the Communist Rivera included a prominent portrait of the Russian revolutionary Lenin in his mural, his patrons had the entire work destroyed.

DIEGO RIVERA IN DETROIT. The most fully realized of Rivera's murals in America was his epic cycle of American industry painted in Detroit under the patronage of Edsel Ford (son of Henry). Rivera arrived in the United States with his wife, the painter Frida Kahlo (1907- 54), in 1930, in response to growing enthusiasm for his work. Following several commissions from patrons in the San Francisco area, including a mural in the San Francisco Stock Exchange, Rivera accepted an invitation from the director of the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) to paint two large murals in the Garden Court at the heart of the Renaissance inspired museum building. Detroit was then dominated by the automobile industry, centered at River Rouge, heart of the Ford empire. The entire project of twenty-seven panels was completed in less than eight months, from July 1932 to March 1933. Rivera, backed by a team of assistants, worked in the true fresco technique he had first studied in Italy in 1920-1: a labor-intensive medium that required three coats of plaster, on-the-spot preparation of pigments, transfer of the design onto the wall, and a carefully plotted, day-by-day application of pigment onto wet plaster.

Rivera was absorbed by the spectacle of American industry. Two large narrative panels on the north and south walls of the court show in exacting detail the stages in the production of a V-8 Ford automobile, based on his on-site observations at the Ford plant. These panels highlight the two main principles behind the Ford manufacturing revolution: assembly-line production and the integration of all stages of the manufacturing process in one vast factory complex, from the production of steel in a blast furnace (north wall)--shown just below the volcano, its· natural counterpart-to the milling, rolling, and stamping of steel, glass manufacture, and motor assembly (south wall). Rivera skillfully montaged the separate stages of the manufacturing process, which occupied ten buildings in the multiacre Rouge plant, into a narrative unity.

The north wall features scenes in the "Production and Manufacture of Engine and Transmission (Ford V-8)" (figs. 16.2 and 16.3). On the lower level Rivera painted a frieze of workers, each representing a different ethnic component of the Detroit workforce, from Bulgarian to Mexican, Japanese, and African American. During a period when Detroit's work force was struggling to bond ethnic divisions together in unions, this vision of multiethnic harmony was a powerful recruiting tool for the city's labor organizers, who rallied in front of Rivera's mural. The south wall shows "The Production of Automobile Exterior and Final Assembly," witnessed by crowds of visitors who gawk at Ford's industrial miracle.

Above the scenes of Detroit labor, Rivera represented the geological sources of industry in the giant hands that hold the limestone, iron ore, and coal used to produce steel. Moving from the scenes of industry up the wall, the viewer proceeds from narrative to allegory, from the historically specific to the universal, and from culture to nature.

In its epic sweep, The Birth of Industry draws parallels between biological processes and technology, and between ancient and modern cultures. The huge stamping press dominating the right side of the south wall was inspired by a sculpture of an Aztec goddess (Coatlicue), who combines the forces of life and death, creation and sacrifice. An organizing theme throughout the mural is the dual potential of technology to deliver both life and death. On the west wall, wartime and peacetime aviation confront each other. Beneath gas-masked fighters Rivera has placed a bird of prey; beneath the domestic aviation industry, a dove. And in the center of the lower panel is a symbolic head, split between life and death.

Animating Rivera's work in the United States was a vision of Pan-Americanism: the rebirth of hemispheric culture through the economic and social integration of North and South America. Pan-Americanism had attracted American industrialists from the turn of the century on, as they looked longingly toward the raw materials of Mexico and South America. Rivera gives the idea a new twist, however, emphasizing the union of indigenous and industrial cultures in a non-exploitative future . His utopian cycle redeems the fragmented industrial present through an image of cosmic wholeness and peace.

Unlike Charles Sheeler's Classic Landscape (see fig. 14.17) , which focuses on the exterior vista of railroad, raw materials, and distant smokestacks at the Rouge plant, Rivera's mural foregrounds the laboring body of the worker, nowhere apparent in Sheeler's work. Months before Rivera arrived in Detroit, workers at the Rouge walked out to protest at a "speed-up" on the assembly line, resulting in a violent clash with police and the deaths of four men (see Box, p. 519) . Human labor was the sticking point of Henry Ford's revolution in production; by placing the industrial worker at the center of his mural, Rivera asserts the importance of the social dimension missing from Sheeler's vision.

JOSÉ CLEMENTE OROZCO AT DARTMOUTH. At the height of American interest in the Mexican muralists, Dartmouth College in New Hampshire invited Jose Clemente Orozco-who went there to teach in 1932-to do an ambitious cycle of murals in the library. Enjoying the enthusiastic support of the faculty and the president of Dartmouth, Orozco embarked on the most extensive fresco cycle completed in the United States to date. It took Michelangelo three years to paint the Book of Genesis on the Sistine Ceiling; it took Orozco about a year and a half to paint his Epic of American Civilization-a topic only slightly less grand than Michelangelo's-onto the 3000 square feet of Baker Library at Dartmouth. The feat was nothing short of heroic; furthermore Orozco, unlike Michelangelo (or Rivera), worked without assistants. The challenge Orozco set for himself at Dartmouth was the creation of a modern myth of the artist-revolutionary as redeemer of a morally and spiritually corrupt social order. He did so in twenty-four separate murals, whose historical reach extended from the ancient Toltec civilization of Mexico's "golden age," through the murderous and war-driven culture of the Aztecs, to the arrival of Cortez and the brutal imposition of a new colonial order. Exemplifying the parallel historical structure within the cycle, Orozco placed the violent autocratic rule of the Aztecs, whose gods demanded human sacrifice, alongside the modern militarized nation state, sending its youth to slaughter while suffocated by patriotic symbols. "Gods of the Modern World, or Stillborn Education" (fig. 16.4) is a savage caricature of modern institutions of higher learning, personified as death's-heads in academic dress who oversee the birth agonies of a skeletal "alma mater" upon a bed of books. The stillbirth of knowledge is represented as a shriveled fetus held by a hunched doctor of death. Orozco's macabre allegory inverts life-giving knowledge into mummified and sterile traditions whose function is to perpetuate entrenched power at the cost of society's dynamic growth.

The hero at the center of Orozco's epic is Quetzalcoatl, an ancient Mexican god and savior figure who brought a message of enlightenment that fostered moral and cultural growth among New World societies. Quetzalcoatl fuses Old Testament prophets with New World symbols of power-snakes (fig. 16.5). His departure heralds the end of the golden age of indigenous societies, and sets the stage for his reappearance in another epoch during which technology-identified throughout the cycle with false godsis transformed into a liberator of human creativity. Orozco's mural, painted in the heart of New England, offered a historical epic centered around the indigenous societies of Mexico, and on the Spanish Conquest in place of Plymouth Rock and other Anglo-centered founding national myths.

Orozco's epic themes echo Rivera's Detroit cycle: the dialectic of good and evil, playing itself out over history, awaits a synthesis fusing North and South, indigenous and European, Old and New Worlds, the mechanical and the organic. Both murals united North and South America in a single trajectory, a hemispheric perspective that countered narrow forms of U.S. nationalism. Orozco's visual imagination, steeped in satire and cartoon-like exaggeration, inspired several generations of political muralists for whom realism was inadequate to portray the grotesque injustices of modern life.

The impact of the Mexican muralists was profound. A trip to Mexico was a virtual requirement for U.S. artists aspiring to a politically and culturally mobilized public art. Mexico offered a different version of America's cultural and artistic origins, looking not to European modernism but to the great civilizations of the New World- the ''.American Sources of Modern Art," as the title of a 1933 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art put it.3 Featuring art of the Maya, Aztec, Zapotec, Inca, and other New World cultures, the exhibition celebrated the formal power and aesthetic value of an art "not derived from the Old World, but originating and growing up here, without models or masters," as Holger Cahill's essay for the catalogue put it. The arts of ancient Mexico also joined Old World and African influences on modernist formal abstraction in both Mexico and the United States.

CHARLES WHITE. The artistic exchange between the United States and Mexico in the decades between the wars left a legacy of public murals, paintings, photographs, and prints. Charles White's The Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America, a mural completed in 1943 for Hampton University (fig. 16.6), draws upon the spatial and temporal condensation and the synoptic reach of the Mexican muralists, to travel across centuries of black history. From a poor neighborhood in Chicago, White (1918-79) pieced together his artistic and political education from exchanges with prominent black and white artists, intellectuals, and writers in Chicago, who pointed the way toward a structural understanding of racism. Like the printmaker Elizabeth Catlett (b. 1915), to whom he was briefly married (see Box, p. 525), White traveled to Mexico after painting murals for the WPA and joining the Negro People's Theater. White structured his epic history around racial and class oppression. At its center is a black architect unrolling a blueprint symbolic of the constructive energies of a liberated race. On the left side are scenes of armed Klansmen and chained black men; and on the other side, leading figures in the black struggle for justice (Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman), along with scientists (George Washington Carver) and anonymous musicians. At the center is a huge dynamo gripped by a bronze colossus recalling the Aztec creator I destroyer beings of Rivera and Orozco- part of a broader symbolism weaving together the forces of life and death, creation and repression. White, like other black artists in these years, saw his people's history as part of a wider struggle of oppressed groups throughout the hemisphere. Race and class oppression exceeding the boundaries of the nation- informed the strong political affinities between American black painters and Mexican muralists.

Social Realism

While public art expressed unifying ideals, artists' organizations engaged with politics more directly. As historical conditions drove artists out of their studios and into activism, they formed alliances with workers to protest the displacement caused by industrial capitalism. Growing disparities of wealth and widespread misery caused intellectuals, artists, and writers in the 1930s to look beyond the status quo toward political philosophies- Marxism most directly-that were critical of capitalism.

Social Realism was rooted in the belief that art was a means with which to change the world order. As the singer I songwriter Woody Guthrie expressed it in a sticker he put on his guitar, "This machine kills fascists." By enhancing people's awareness of their place within an exploitative social order, artists, musicians, and writers could also radicalize them.

BEN SHAHN. The execution in 1927 of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian immigrant workingmen from Braintree, Massachusetts, provoked outrage around the world. Many observers were convinced that the two avowed anarchists were executed for their political beliefs rather than for any complicity in the 1920 murder of a paymaster and his guard during a robbery at the shoe factory where Sacco was employed. The closely watched trial crystallized the growing sense that the United States was betraying its democratic legacy of civil rights, its embrace of immigrants, and its vaunted system of justice for all.

For Ben Shahn (1898-1969), a young artist struggling to find his voice, the event helped to turn him away from his pursuit of French art, to which many American artists still felt they must apprentice themselves. "Here," he wrote years later, "was something to paint,"4 a subject both monumental and timely. The story of the two Italian immigrants, their families and communities, and their trial, developed into a series of images in many different media. Of these, the best known is Shahn's The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti (p. 516). Shahn's theme here is the hypocrisy of the powerful in the presence of martyrdom. In the foreground, three men-the so-called Lowell Committee appointed to review the case for the State of Massachusetts-pay their respects at the coffins of the executed men, gazing vacantly past the bodies. They are Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell (center), MIT President Samuel W Stratton (left), and Judge Robert Grant (right). Judge Webster Thayer is pictured, like a wooden idol in the background, taking the oath to support justice. Dispensing with consistent scale, perspective, and illusionistic shading, Shahn developed a style that combined the naive drawing of children's and "folk" art with the monumental humanist art of the early Renaissance. While Shahn clearly learned a great deal from European modernism, he rejected its arcane concerns.

The Continuing Relevance of Mexican Art

MEXICAN ART between the wars has continued to influence community art forms, including murals and prints, attacking U.S. imperialism. Elizabeth Catlett's Latin America Says "No!" of 1963 (fig. 16.7) summarizes the history of U.S. military interventions throughout Latin America, from Guatemala to Cuba, Chile, and El Salvador, on behalf of American corporations threatened by nationalization of industries. A rifle-wielding U.S. soldier resembling a death's-head, his standard issue army helmet bearing a dollar sign, confronts two peasants-a man and a woman-barring access to the land, people, and wealth of Latin America. The graphic simplification and allegorical reduction of Catlett's print reveal the impact of the political print styles she had absorbed as an artist in Mexico from 1946 on. Catlett had worked briefly for the Public Works of Art Project, one of the initial projects of the New Deal; she studied painting, ceramics, and printmaking at the Art Students' League and elsewhere in the United States before traveling south. Catlett soon joined the "Taller de Grafica Popular." Founded in 1937, the Taller was a collective of politically active printmakers in Mexico City who produced posters, prints, and broadsides for popular distribution on such subjects as literacy, land expropriation , and popular resistance. Like other African American artists, Catlett identified black struggles for equality with the goals of the Mexican revolution. Catlett has remained in Mexico up to the present, her interests encompassing hemispheric popular movements against entrenched power.

PHILIP EVERGOOD. For Philip Evergood (1901-73), politics and art were intimately linked. As he wrote regarding his 1937 painting American Tragedy (fig. 16.8), "I don't think anybody who hasn't been really beaten up by the police badly, as I have, could have painted" such a work.5 American Tragedy shows-in the starkest possible terms-a confrontation between steelworkers, their families, and armed police in front of the South Chicago plant of Republic Steel. As part of an effort to organize the smaller steel companies following the unionization of workers at U.S. Steel, the Steel Workers' Union held a rally and parade on Memorial Day 1937. As recounted in Paul Strand's film Native Land, made by the film collective Nykino in 1942, the festive atmosphere of the demonstration ended violently when the unarmed marchers were attacked and fired upon by the Chicago police, leaving eleven men dead, and over a hundred injured. The effort to derail the union through violence succeeded only in the short term. Union members were laid off, or returned to work under a cloud. Eventually, the right to unionize was upheld by the Congressional committee that investigated the episode.

Evergood's figurative style is deliberately crude and caricatural; workers and their wives, dressed in Sunday best, flee, stagger, and collapse before the bullets and batons of police. On the left, a black worker has fallen, still clutching a small American flag in his hand-Evergood's tribute to the patriotism sustaining the movement for workers' rights. At the center, a pregnant Hispanic woman arms herself with a stick and shakes her fist at a gun-wielding policeman who points his gun at her belly while her husband grabs him by the coat. This act of defiance in the face of violence and intimidation holds the key to Evergood's drama. Its title universalizes the action, removing it from immediate events to occupy a bigger historical stage, as one episode in a broader struggle. Through cartoon-like exaggeration, a deliberately harsh color scheme, and distortions of scale and perspective, Evergood turns away from the idealized figural tradition of the Old Masters toward what the writer and philosopher Kenneth Burke called "the proletarian grotesque" -a vision of embattled humanity inspired by the Spanish artist Franciso Goya (1746- 1828) and others who had grappled with the contorted features of human extremity.

Epics of Migration

A defining impulse of the 1930s was to set down roots, to search out a usable past that would anchor the nation in a time of crisis. Yet it found expression in the face of widespread human displacement- a massive uprooting of Americans in search of employment, new homes, more fertile lands. Migration between worlds had been the defining experience for Americans from Africa, Asia, and Europe over four centuries of history. Men and women of different regional, ethnic, social, and educational backgrounds found themselves poised between old and new worlds, tradition and modernity, historical limitations and future possibilities. From pioneers to the American West, to European and Asian immigrants in search of new opportunities, they carried, in the memorable image of the black poet Langston Hughes (1902- 67), the seeds of new cultures "from far-off places/ Growing in soil/ That's strange and thin,/Hybrid plants/ In another's garden" ("Black Seed," 1930). Hughes was writing about the great southern migration to the North, but his images apply to any people on the move between cultures.

The epic of human migration took a number of visual forms in the 1930s, the reverse of the frontier myth of America as land of opportunity for new immigrants. Two of the greatest internal migrations in the twentieth century occurred during the years between the wars: the Dust Bowl migration, primarily of white grain farmers to California in the 1930s; and the movement of black sharecroppers out of the South toward the industrial cities of the North. In image after image of people displaced from their homes, migration in the 1930s emerged not as a search for new horizons but as a desperate flight from unsupportable lives and devastated lands.

JACOB LAWRENCE. Jacob Lawrence's The Migration Series (1941), done when the artist was only twenty-three, offers a black perspective on the national drama of peoples in transition. Consisting of sixty small panels, it was one of several focusing on black history that Lawrence (1917- 2000) did over his long career (fig. 16.9). Lawrence worked in series because, as he put it, the artist cannot "tell a story in a single painting."6 In doing so, he also gave visual expression to the African American tradition of oral narrative. The Migration Series fused this ethnic inheritance with the broader 1930s narrative impulse. He was communal storyteller, historian, poet, and mythmaker all at once, telling a tale of the shift "from medieval America to modern," in the words of Alain Locke.7

Following the Civil War, a feudal system of rural sharecropping had betrayed the promise of emancipation, reducing black families to peonage. Responding to labor shortages following World War I, and the lure of better wages that promised a way out of chronic indebtedness and poverty, black sharecroppers migrated north to fill industrial jobs. By the conclusion of World War II, nearly half the black population in the United States lived in cities. Lawrence's series represented the labor camps, poor and crowded housing, discrimination, riots and violence, disease, and class prejudice that accompanied the pursuit of economic and social betterment- voting rights and education-in the North.

Lawrence presented his migration story in the stark imagery of colluding forces pushing black families out of the South and pulling them northward toward new opportunities. He devised a recurring symbolism of thresholds, crossroads, bus and train stations, ladders, stairs, barriers, bars, and boundaries to suggest the passage from South to North and rural to modern. Stylistically as well, Lawrence's series represented a movement between worlds. His simplified, silhouetted human forms painted in broad, uninflected fields of vivid ochers, yellows, blues, rust reds, and forest greens, bring together the tilted and flattened spaces of Post-Impressionism with the intense colors of Lawrence's youth in Harlem. There his eye was first educated in the rich and colorful streetscapes shaped by rural black migrants who brought with them the memory of rural patchwork quilts. He drew as well upon the black oral traditions that connected rural past with urban present, even as the easel format in which he chose to tell his story was inherited from the Christian and classical narratives of the Italian Renaissance. Terse captions accompanied each panel, advancing the story through a few expressive elements.

In its subsequent history, The Migration Series also migrated between the two worlds of black art and white patronage, interrupting a practice of cultural segregation that had long kept black artists out of white galleries. Lawrence was the first African American to benefit from the initiatives of Edith Halpert, a prominent galleriste and patron of both modern and folk art in Manhattan, and, like Lawrence, an emigree from another land. Born into a Jewish family from Odessa, Russia, she had arrived in Harlem as a young child to begin a new life. By 1926 she had opened an art gallery, motivated by a desire to democratize American art by promoting its affordability, and by drawing attention to the exclusion of black artists by white dealers and galleries. Exhibited at her Downtown Gallery in 1941, the series drew the support of Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art, and Duncan Phillips, founder of the Phillips Collection of modern American and European art in Washington, D.C. Each man purchased half the series, or thirty canvases each.

Lawrence's narrative was grounded in his historical research at the Schomburg Library in Harlem as well as his family's own experience migrating from the South to the North. The theme of cultural migration between worlds had been taken up by the poet Langston Hughes, the musicians Duke Ellington and Muddy Waters,. and the novelists Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison. To his rich mix of influences, Lawrence's 1930s schooling in the American left added an understanding of the role played by an oppressed racial group in the larger national story, through its labor, its quest for full humanity, and its investment in the American dream of self-betterment.

Lawrence's emphasis on black identity as a product of culture and history was part of a broader reaction against the idea of race as a biological given, and a new emphasis on environment in shaping human experience and identity. The new field of cultural anthropology played an important role in bringing about a revaluation of non-European cultures, especially African and Native American. Critical in this rethinking was the work of the Columbia University anthropologist Franz Boas, who helped pioneer the field of cultural anthropology. Boas pointed the way for a cultural relativism that by the 1930s was widely accepted by progressive thinkers in the United States and that worked against forms of racial essentialism, the belief that identity is fixed at birth. The study of cultural anthropology helped undermine the cultural hierarchies that had long consigned non-white societies to inferiority as measured against a standard derived from the European mainstream.

AARON DOUGLAS. The will to transform a history of oppression into a new collective identity guided a second important painting cycle between the wars: Aaron Douglas's (1899-1979) four-part Aspects of Negro Life (1934), painted for Countee Cullen Branch of the New York Public Library, in Harlem, under the patronage of the PWAP (Public Works of Art Project), a predecessor of the WPA. In Song of the Towers (fig. 16.10 ), a musician, standing on a giant cogwheel symbolizing industry, suggests the fate of the southern migrant-from slavery to industrial enslavement in the crushing discipline of the factory. Douglas's saxophonist stands triumphant above the grasping hands that draw others down into a feudal past, but his liberation is temporary, for the cog will carry him back down into the bowels of the city. Located at the center of the composition, his raised right arm beckons the distant figure of the Statue of Liberty, a mirage of unrealized freedom that floats between the faceted skyscrapers looming over the foreground. Aspects of Negro Life unfolds the voyage of African Americans from Africa, shown in the opening canvas of silhouetted dancers who embody a primitivist fantasy of tribal rhythm, to plantation life under slavery, to the Civil War, Emancipation, and Jim Crow, concluding the journey with apparent pessimism in the modern city.

Douglas, like other artists in these years, was a member of the Communist Party USA, an organization that supported African Americans' struggle for racial equality and economic justice. In Song of the Towers, musical expression becomes a cry for freedom. Douglas's saxophonist remains precariously balanced atop the great cogwheel, recalling the enormous industrial gears that draw in the Tramp in Chaplin's Modern Times (see box, page 519). But the black musician also draws upon his prophetic powers to "wake the living nations," in the words of the black poet James Weldon Johnson (God's Trombones), who used religious oratory, ragtime, and spirituals to lay claim to the great forms of Western culture and epic poetry: Douglas translated jazz rhythm and improvisation into visual terms: concentric circles suggest sound emanating from raised instruments, syncopated by the intercepting silhouetted figures. In his speech at the First American Artists' Congress in 1936, Douglas made his case for why black artists should look to vernacular traditions such as jazz and dance rather than to visual traditions rooted in Europe. The task of the black artist was to give "creative expression to a traditionless people .. . [he] is essentially a product of the masses and can never take a position above or beyond their level." Jazz was a New World art form, its potential to liberate expressed in the face of an oppressive history.8

DIS-ARTICULATING IDENTITY: ISAMU NOGUCHI. Conservative forms of nationalism in the decades between the wars grounded identity in place and in an exclusionary racial inheritance. In these same years, artists such as Lawrence, Douglas, and, slightly later, Isamu Noguchi (1904- 88), were exploring identity through experiences of mobility, dislocation, and hybridity. Noguchi was an American sculptor of mixed parentage (Japanese, Scottish, and Native American). Criticized in the 1930s for his graphic portrayal of a lynching victim, Noguchi turned to abstraction in the war years. The scholar Arny Lyford has argued that Noguchi's work in these years carries the traces of his own struggle against racial typing.9 In 1945, the final year of World War II, Noguchi took on a theme with roots in Western culture, that of the kouros, the standing young man of ancient Greece, the archaic expression of male wholeness and strength. Noguchi's Kouros (fig. 16.11) consists of thin polished marble forms slotted and notched together in a tense balance. Readily disassembled and transported, Kouros challenges the Western tradition by reconstituting the figure as a precarious arrangement of solids and voids in place of the gravity and weight of the older tradition.

Noguchi had reasons to challenge these older traditions based in the stable human form. Though an American citizen, he was interned briefly during World War II with other Americans of Japanese descent who were relocated to concentration camps throughout the American West. In the fever of war, the loyalty of Japanese Americans was cast into doubt, along with their claims to citizenship, purely because of their ancestry. The race-based internment of U.S. citizens resembled policies in fascist Germany and Italy, where the classical tradition had been propagandistically associated with a particular racial type. Noguchi's deliberate dis-articulation of the body in Kouros symbolically associates identity with something that is literally constructed, and easily disassembled for portability. "To be hybrid," he wrote in 1942, "anticipates the future. " Noguchi understood and affirmed the challenge mixed-race individuals posed to constructions of identity grounded in racial purity and "essence" and linked to an exclusionary definition of the nation.

Anti-Fascism and the Democratic Front: Abstraction and Social Surrealism

Surrealism and abstraction, two art forms associated with modernism, also found a place within wider debates about the social and political relevance of artistic style and content.

For many artists in the 1930s, Social Realism was inadequate to express the irrationalities of mass hunger amidst wealth, or the grotesque spectacle of fascism abroad and political reaction at home. Stuart Davis (1894- 1964) was unusual in giving his commitment to abstraction a more direct political rationale. In these years Davis decried what he termed "domestic naturalism" as an evasion of present realities. In his thinking, realism and naturalism, by presenting an illusion of the real, condoned the way things were, and gave legitimacy to the structures of power that needed to be exposed. For Davis, abstraction uncoupled the appearance of things from their underlying reality, and freed people to rethink the social order. Davis was one of twelve artists, including Willem de Kooning-most of whom painted abstractly-who were commissioned to paint murals for the newly completed Williamsburg Housing Project in Brooklyn in 1937. This public project of twenty four-story buildings was designed by a modernist architect; the murals within were unusual in choosing abstraction for a public commission. Up to that time, such commissions had favored figural and narrative art over abstract or "avant-garde" styles. Davis's Study for Swing Landscape (fig. 16.12) weaves together motifs from the waterfront/ wharf area-buoys, ladders, rope and rigging, and lobster traps-in an eye-dazzling array of saturated colors intended both to stimulate and to relax his working-class audience. Committed to abstraction as a progressive new democratic art accessible to ordinary Americans, Davis referred to his work as a new form of realism-antinaturalistic, yet tied to the realities of an interracial society, and embodying the spatial and temporal disjunctions of modernity. The title refers to jazz, a musical language that crossed color lines and represented for Davis something both modern and American. Swing Landscape synaesthetically recreates the syncopated rhythms and instrumental colorism of the swing bands of the late 1930s.

Davis's mural was not in the end installed at Williamsburg, though it is today among his best-known works. Although an abstraction, Swing Landscape went out of its way to engage its intended audience. Through its scale, bright colors, and references to everyday objects and to swing music, it was intended to appeal across a wide social spectrum from black to Jewish and white ethnic groups. Swing Landscape both expressed and helped to create a pluralistic, ethnically and socially inclusive "people's culture," using everyday subjects that communicated to the masses in familiar terms: jazz, sports, popular film, cartoons, radio, and theater. Swing Landscape embodied the cultural politics of the Popular Front, the American version of the international Communist Party's turn toward a more accessible language and movement beyond narrowly proletarian themes. The Democratic Front aspired to forms of artistic expression that grew out of, and in turn supported, the organizing efforts of American unions and other popular movements. Davis himself was active in radical politics; his own brand of modernism- recognizable objects montaged into dynamic compositions-integrated aesthetically radical form with a progressive social vision.

In 1937, the town of Guernica in Spain was bombed by German planes allied to the reactionary Loyalist forces of General Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. The event provoked international outrage and inspired Picasso's Guernica, a mural-sized, monochrome painting that became a rallying point for artists on the left.

Like Guernica, Louis Guglielmi's Mental Geography (fig. 16.13) responded to the Spanish Civil War in an image intended to mobilize its audiences through symbols that pushed beyond immediate events. Years later Guglielmi wrote that he had pictured the imagined destruction of the Brooklyn Bridge "after an air raid: the towers bomb-pocked, the cables a mass of twisted debris. I meant to say that an era had ended and that the rivers of Spain flowed to the Atlantic and mixed with our waters as well."10

Guglielmi was one of a group of artists in the 1930s who found Social Realism inadequate to the political and social realities of the present. Called Social Surrealists, they used techniques associated with European Surrealism: condensing time and space, montaging elements together, juxtaposing objects in an apparently illogical manner, and creating scenes which,_ while improbable, conveyed a poetic or imaginative truth at a time when social values were often inverted in practice. Social Surrealists drew on fantasy and subjective experience in order to expand the reach of Social Realism, but retained that movement's concern for an art that communicated broad social themes. Combining two languages not normally linked-the language of the unconscious and the language of social concern- they focused on themes of racial and social injustice, poverty in a land of plenty, and institutional abuses of power. They aimed, like European Surrealists, to reorder society through the unmasking power of imagination. However, Social Surrealists dispensed with the psychological landscapes that dominated Surrealism. They preferred instead to explore the injustices of the social order while sharing with other movements a desire to expand beyond the narrative limitations of older art forms.

In the 1930s, the mass dissemination of political ideologies through radio and film offered a troubling new form of mass "enlightenment," the machinery of propaganda through which Adolf Hitler, elected in Germany in 1933, established his sway. American filmmakers such as Orson Welles (1915- 85; Citizen Kane in 1939) and Frank Capra (1897-1991; fig. 16.14) took on the power of mass media to shape public attitudes as well as its misuses by the forces of political reaction. In Capra's film a homeless man ("John Doe"), played by Gary Cooper, becomes an unwitting player in a well-intentioned newspaper ploy to increase circulation. The gambit, however, spins out of control; in the penultimate scene, which deliberately evokes Hitler's Nuremberg rallies, John Doe repudiates the role of charismatic leader of the people to which he has, against his will, been raised by the combined force of popular gullibility and media manipulation.