13.4: Architectural Encounters- Transnational Circuits

- Page ID

- 232344

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)As with other areas of American arts and culture, architecture benefitted enormously from transnational exchanges in the opening decades of the twentieth century. But in this instance, these stimulations came not just from Europe but from Japan. World's Fairs (those of 1876 and 1893 in particular) had played a central role in exposing American designers to non-Western influences. This engagement with Asian arts continued into the twentieth century, as designers such as Frank Lloyd Wright and the Greene brothers of Pasadena-reacting against the eclectic clutter of late Victorian taste-turned to Japanese aesthetic principles of visual harmony and motifs stylized from natural forms. What they learned would play a central role in the emergence of a new modern American architecture integrated with nature. The modern movement, in both the United States and Europe, would come to associate visual clutter and spatial congestion with disease; the open plan, allowing free spatial flow and open sightlines, was linked to the space and light associated with good hygiene. Meshing with native concerns, such ideas were also introduced into the United States by such emigre architects as Richard Neutra (1892-1970), who was apprenticed to Wright. The emergence of a modern American architecture is a pronounced example of how contact with international influences not only challenged older canons but also reinforced longstanding ideas about the role of architecture in shaping and reflecting national culture.

The Early Career of Frank Lloyd Wright

Born in 1867, Frank Lloyd Wright came, over a very long career (from 1896 to his death in 1959 ), to be considered a uniquely American architect, steeped in the traditions of Jeffersonian thought, individualism, organic design, and nature. No one contributed more to the myth of Wright than Wright himself. Possessed of an extraordinary sense of mission, he promoted his ideas about architecture, individualism, and democracy through books, lectures, and his own foundation, Taliesin, in Wisconsin. Through the ups and downs of his career-including years in the 1920s when he built very little-Wright emerged as a visionary figure, adapting a core language of elemental forms to the evolving needs of the twentieth century, from domestic suburban design to large-scale corporate office buildings, planned communities, skyscrapers, and museums.

Coming out of Wisconsin, Wright identified himself with the landscape of the rural Midwest. In 1887 he went to Chicago, where he began his career in the office of Louis Sullivan. By 1892 he was in practice for himself in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, where he built a studio and home. Here, from 1892 until his sudden departure for Europe in 1909, he developed his "Prairie Style," a regional school of reform design that would have an international influence.

Wright's "Prairie Style" was heralded by later historians as a turning point in the design of the American house, and-more than that-in the emergence of an independent American architecture. And yet in his search for a new architecture expressive of American democracy, Wright, like Sullivan, turned to non-Western sources. He learned a great deal about abstraction and simplification of natural forms from his extensive collection of Japanese prints: in his Autobiography he wrote that "The gospel of elimination preached by the print came home to me in architecture ... it lies at the bottom of all this so-called 'modernisme."'21 Wright's stylized ornament developed-in tandem with his incorporation of machine production-into his own organic design philosophy. From Owen Jones's Grammar of Ornament (1856)-an English compendium of decorative motifs from around the world, Indian, Chinese, Egyptian, Assyrian, Celtic, and more-both Wright and his teacher Sullivan encountered geometricized abstract patterns that would influence their own approach to form. Wright was proud to acknowledge these non-Western sources in his design philosophy, while playing down European influences.

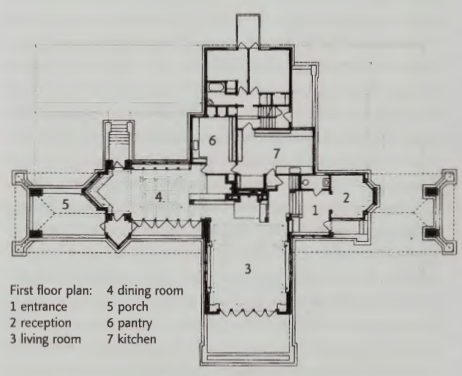

Figure 13.27 A, B: FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT, Ward Willits House, facade and plan, 1902-03. Crayon, gouache, ink, and ink wash on paper, 8½ x 32 in (21.5 x 81.2 cm). Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

Wright's most important innovation of the Prairie years was the so-called "open plan," which dramatically changed the character of domestic space by removing interior walls, "dynamiting" the boxlike forms of the past, substituting partitions, and allowing for a more fluid circulation from room to room. Wood trim, flush with the wall surface, furnished ornamental accents. Wright's Prairie Style homes are characterized by long horizontal expanses with deep overhangs. Japanese architecture, as well as prints, played its part. The genesis for this new conception of space may well have been Wright's first encounter with Japanese buildings at the Chicago World's Fair of 1893, followed by a trip to Japan in 1905. In Chicago he saw for the first time the deep roof overhangs, interpenetrating interior spaces, and exposure of the wooden structural system as part of an overall aesthetic. The street facade of the Ward Willits house in the Chicago suburb of Highland Park (fig. 13.27) presents a long horizontal massing punctuated by a two-story central core. Here as elsewhere there is no attic; instead the hipped roof allows for an expansive second floor. Horizontal wood banding accenting the smooth surfaces of the house emphasizes its abstract geometries.

From Japanese domestic dwellings he may have also learned the lesson of a central focus. In many of Wright's houses, the fireplace not only anchors the cross-axes of the plan, but also serves as a symbolic focus of family life, a vertical accent that breaks the horizontal emphasis of the Prairie Style and suggests the presence of the father and household head. Prairie Style homes, with their central hearths and sheltering overhangs, created a strong feeling of refuge from the world without, linked to older Victorian notions of the separation between public and private spheres. Unlike later International Style architects, Wright rejected expansive use of glass to bring in light; his early houses (such as Willits) incorporate the landscape through porches but they also embody ancient notions of shelter with long, lowslung rooflines. Leaded casement windows filter light, allowing residents to see out without being seen. Such conservative features earned for Wright the dubious distinction of being 'America's greatest nineteenth-century architect,"22 in the words of modernist architect Philip Johnson.

Yet Wright's Prairie Style also paralleled the broader reforms in architecture linking America and Europe-in particular the Arts and Crafts movement-in such features as the use of structural elements in place of applied ornament and in the creation of aesthetically integrated environments. When possible, as at the Dana House in Springfield, Illinois (fig. 13.28), Wright and his office designed everything, from the stained glass to decorative murals, furniture, textiles, lighting, fountains, and sculpture. Visual unity and harmony reinforced efficient housekeeping practices. Wright, influenced by feminism, believed in simplifying the work of women by abolishing clutter, simplifying and flattening surfaces for easier cleaning.

Despite the concern with developing a national building style, architecture in the United States during these years was an international practice, and Wright's style was no exception. In addition to the influence of Japanese design, he kept abreast of European developments through architectural journals carrying the latest ideas, along with halftone illustrations that conveyed a more direct understanding of the new building. In 1910 a trip to Europe reinforced these influences in Wright's own evolving practice.

The occasion for this trip was the publication of a deluxe edition of his work by a Berlin publisher. The so called Wasmuth edition brought Wright's innovative Prairie Style to the attention of advanced designers in Germany, Britain, and Holland, who recognized affinities with their own reforms. On both sides of the Atlantic, leading architects were turning to non-classical sources, and to the basic geometry of squares and circles. Wright had already encountered advanced European architecture at the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, where he was much impressed by the style of the German and Viennese Secession. Breaking away from the dominant historicism of academic practice, these architectural reform movements offered Wright the example of simplified, bold massing and an elegant geometry of cubes and squares. Following such leads, Wright in turn explored Mayan, Egyptian, and Near Eastern design traditions, where he found the monumental forms and the symbolic power of simple shapes that underlay much of his later practice. This work will be examined in Chapters 16 and 17.

American Architecture Abroad

It is a commonplace that American art began to have an international presence only with the appearance of Abstract Expressionism, the "triumph" of American painting. Yet well before the New York School gained international prominence, American architects and their buildings were winning the admiration of critics, designers, and theorists throughout Europe. And they were transforming ideas about urbanism, construction methods, and expressive forms in ways that had an enduring impact on the development of European modernism.

Europeans recognized the skyscraper as an American type, and traced it to the architecture of the Chicago business section known as the Loop. Architects of the early modern movement visited Chicago to learn from the Loop; they avidly studied Sullivan's Schlesinger and Mayer department store (see Chapter 10). By the 1920s, the Schlesinger and Mayer building had become something of a landmark in European histories of modernism; the German modernist Walter Gropius (1883-1969) pronounced in 1938 that had the European avant-garde known about Sullivan's accomplishments earlier, it would have accelerated their exploration of modernism by some fifteen years. The Chicago school of skyscraper design inspired Gropius's own 1922 entry for the Chicago Tribune competition. Gropius-who would later become head of the Graduate School of Design at Harvard-admired Frank Lloyd Wright's modular geometries; he later identified the European edition of Wright's work as the "office bible."

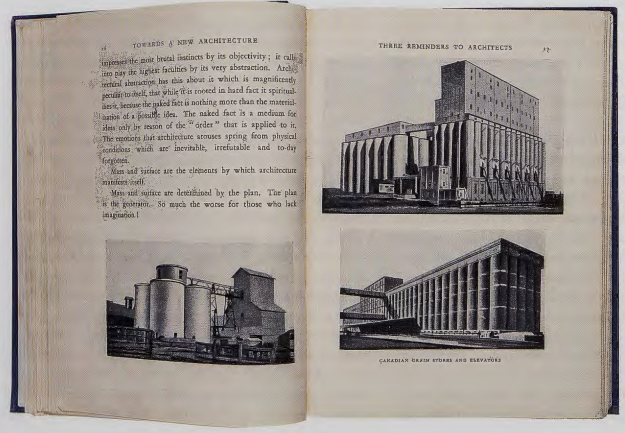

"SILO DREAMS": AMERICAN INDUSTRIAL ARCHITECTURE AND EUROPEAN MODERNISM. European architects learned from the large-scale industrial infrastructure and the movement through space that characterized American modernity. Beneath the classical forms of the buildings at the Chicago World's Fair they discovered an exciting new use of structural iron that, stripped of its fussy historical dress, conveyed to them the lessons of modern industrial materials and functional design. From American architecture, they learned how a coordinated approach to urban space such as that on view at the World's Fair could integrate systems of lighting, transportation, circulation, and landscaping. The functionality of utilitarian structures such as grain elevators, highways, and bridges, inspired a European romance with massive built forms, engineered design, and the infrastructure of speed. The American engineer became an international hero.

The phrase "silo dreams" was the German architect Erich Mendelsohn's. Mendelsohn (1887-1953) was one of many European modernists who found in American concrete construction the realization of their own quest for a monumental, functional architecture of pure geometries uncompromised by references to historical forms. Unfettered by centuries of European tradition, American builders had been able to approach the needs of modern industry directly. Grain elevators, invented by the engineer Charles Turner in 1905, were the most visible and dramatic expression of the possibilities of concrete construction. Reinforced concrete, unlike steel frame, was fireproof, and required no added facing to resist a melting point. By 1910 cement was used some 1500 times more than in 1880. For Europeans this new aesthetic signified a liberation from history. Photographs of American elevators and factories were first published in Germany in 1913, and again in 1925, when they appeared in a book that announced the new structural logic by the Swiss-born modernist Le Corbusier (1887-1965) (fig. 13.29). Widely circulated among Europe's architectural vanguard, these photographs unleashed an ardent admiration for the unselfconsciously straightforward approach taken by American builders. European architects appropriated these utilitarian forms as antecedents that gave weight to their program of architectural reform.

At the forefront of design education internationally between the wars was the Bauhaus, first established in Weimar, Germany, in 1919. The Bauhaus offered an integrated design curriculum that aimed to eliminate the distinctions between art and craft, and to encourage a rigorous approach to design solutions grounded in the new principles of functionalism, rationalism, and efficiency. Its director Walter Gropius closed the school in 1933 in an atmosphere of deepening repression with the Nazi rise to power.

The belief that society could be aesthetically redeemed through improved design was at the heart of the Bauhaus's influential design philosophy and its curriculum of study. Partially shaping that design philosophy was the European reaction to U.S. industrial and engineering structures. Here, as in other areas of the European encounter with American culture, European modernists repudiated America's official high culture and academic architecture, while admiring and emulating its pragmatic solutions to the challenges of modern industry, mechanization, and media. "Our engineers are healthy and virile, active and useful, balanced and happy in their work. Our architects are disillusioned and unemployed, boastful or peevish," wrote Le Corbusier.23 Certainly, surveying the motley variety of American architectural styles- from Romanesque to Aztec, Mayan, Gothic, and "modernistic" or streamlined-a rational approach to design, based in simple geometries, seemed the most promising.

"Virile" European modernists thus took what they needed from the American grain elevator and factory, which they romanticized as the "primitive" expression of anonymous builders while renouncing the effete and outmoded productions of architectural historicists. In truth the factories and grain elevators that first utilized the construction possibilities of concrete were the product of trained architects, working outside the large urban centers for clients who needed cost-effective buildings solving specific problems of space and industrial process.

The structural and design innovations of European modernists, inspired by their encounter with American concrete and steel engineering in the pre-World War I years, in turn were critical to the rise of post-war architectural modernism in America. German emigre architects fleeing the rise of fascism and the outbreak of World War II carried this new functionalist approach across the Atlantic, where it came to be known as the "International Style," and its design philosophy became the basis for architectural education at such institutions as Harvard and the Illinois Institute of Technology (see Chapter 17).

In one more turn of the wheel, American modernists rediscovered their own native industrial buildings through the eyes of European modernists. Without the example of Gropius, Le Corbusier, and others, one wonders whether American artists and architects would have recognized their power and beauty as symbols of this proud American building vernacular.

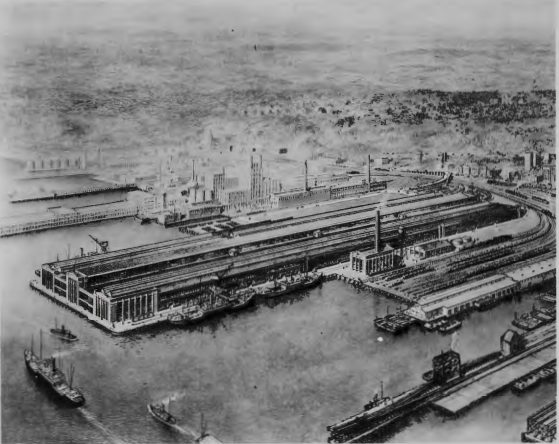

THE MODERN AMERICAN INDUSTRIAL FACTORY. Along with new construction techniques, materials, and structural rationalism, a related innovation in American industrial architecture had far-reaching effects on industry internationally: the reorganization of factory space to create a horizontal continuity between the various phases of industrial production (fig. 13.30). Flow- through space and in time-became the aim of state-of-the-art factory space. Facilitating flow was the removal of spatial barriers and the minimization of columnar supports-both made possible by advances in the technical abilities of steel and concrete to span large spaces with minimal support. In the pioneering architecture of Albert Kahn (1869-1942), factories went from multiple to single-story, horizontally extended structures containing the various phases of the production process. The new face of industry was quickly exported to Europe and Russia, where it played a role in the massive industrialization of Soviet agriculture. A related innovation was the assembly line (first put into place at Henry Ford's Model-T automobile plant in 1913), in which parts moved past the workers, rather than workers being brought to the parts. In its most fully developed form, at Ford's River Rouge Plant in Dearborn, Michigan (built between 1917 and 1925), an internal system of canals and railroads brought raw materials to the building complex and then distributed them to their respective work areas, each representing a phase in a continuous cycle of production that included the manufacture of iron, cement, steel, glass, and rubber (see fig. 14.17). The reorganization of space and time in the twentieth-century system of American manufacturing would be exported to countries throughout the world in succeeding decades, narrowing the gap between the United States and the rest of the world.