10.3: Reform and Innovation- Handcraft and Mechanization in the Decorative Arts, 1860-1900

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Since the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the fine arts have been defined as separate from the medieval craft tradition. Within Renaissance art theory, the artist was motivated by humanist ideals of creative freedom, while the artisan was preoccupied by the problems of craft, or techne, defined by everyday utilitarian requirements. Creative choice was opposed to necessity, art to craft, and intellectual, religious, or symbolic meaning to use-value. In the later nineteenth century, artists began questioning such polarities. As industrial manufacturing transformed every aspect of life in the later nineteenth century, artists and theorists in England- and slightly later in the United States- turned to older craft methods of workmanship as an arena in which to reconnect hand and brain, a link severed by machine manufacture. They found in beautifully designed and crafted objects a way of counteracting the spiritually numbing effects of machine-made goods. By bridging art and life, artist-craftsmen also rejected the isolation of art in museums and private collections, instead applying aesthetic concerns to utilitarian objects and everyday environments. Advocates of what would come to be known as the Arts and Crafts movement (English, originating in the mid-century, reaching its height in the 1880s) and those of the associated "Aesthetic movement" promoted the idea that in choosing household furnishings, consumers also shaped the moral and social environment. As one contemporary, a Chicago sociologist (C. R. Henderson), put it in 1897, "Our works and our surroundings corrupt or refine our souls."19

Origins in Social Theory

The idea that the physical environment in which people live could be "designed" to fit social values had its origins in the later nineteenth century, as part of a broad critical reaction to the historical effects of industrialization. This reaction occurred most profoundly in England, where it focused on the nature of industrial labor and its products. English social critics such as Thomas Carlyle in the mid-nineteenth century, and later John Ruskin and William Morris (all three widely read in the United States), analyzed the manner in which factory production fragmented the work process, replaced hand labor with machines, and subjected the worker to a mindless repetitive process that drained labor and its products of meaning and wholeness. Mechanization had made possible a culture of replication, in which factories could now turn out versions of historical furniture and decorative arts originally produced by hand: Rococo-inspired curvilinear chairs and sofas; garlands of fruit and flowers mounted onto massive Renaissance Revival sideboards; pressed wood urns and classical heads; heavy upholstery; and chromolithographs that reproduced oil paintings (see fig. 9.20). Fueled by a growing urban middle class clamoring for affordable goods with a luxury look, machine manufacture forever changed the look of everyday life.

Beginning with the English Arts and Crafts movement, designers in Europe and the United States wished to restore labor to a central place in community life, by returning control of the labor process to the worker. They advocated a revival of the workmanship they associated with the medieval era, and urged laborers to seek creative fulfillment in work and in an "organic" integration of life and work to replace the separation of work and home, designer and fabricator. These design reforms were not tied to any one historical style; rather than imitating forms from the past, the reformers sought their underlying principles of design. These reform movements drew freely from medieval, Japanese, and Islamic art, and from a range of national vernaculars, stylizing historical motifs but also, in the case of the most original designers-such as Frank Lloyd Wright-inventing new design vocabularies. Design reform embraced not only handcraft but also machine production, subordinated to the will of the designer. The movement for design reform spread throughout Europe and the United States as designers actively exchanged ideas across national borders. Here again, World's Fairs played an important role.

Motivating design reform was the quest for aesthetic simplification. In response to the clutter, visual overload, and over-upholstered excesses of the High Victorian era, design reforms strove to harmonize furnishings, frieze decorations, tile work, rugs, and fabrics to form a complete, visually integrated whole. Advocates of "art in industry" and those who hoped to revive handcrafts both found inspiration in the ideal of an aesthetically integrated environment as a total work of art bringing painters, sculptors, designers, and architects together in collaboration.

A number of institutions for training designers appeared in these years in response to the call for improved design in industry: the Pratt Institute and Cooper Union in New York; the School of Art at Washington University; and the California College of Arts and Crafts, among others. All of them traced their roots to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, established after the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition to address the perceived inadequacies of Victorian design.

HERTER BROTHERS. The Herter Brothers-leading producers of fine furniture in New York during the 1870s and 1880s-combined exquisite design with costly materials and highly skilled handcraft. They provided furnishings for America's wealthy-the Vanderbilts, J. Pierpont Morgan, and others-and collaborated with some of the leading architects of these years. Their studied eclecticism drew upon a range of historical styles-classical, Louis XVI, Japanese, Gothic, Moorish; the currency of a transatlantic community of designers who exchanged influences and friendships. The Herters' Desk of 1882 (fig. 10.26), made for the financier Jay Gould, is in a style known as ''Anglo-Japanese." Its ebonized finish resembles Japanese lacquer work, while its stylized bi-symmetric floral inlay, restrained rectilinearity, and flat patterned approach to decoration recall the leading principles of international design reform.

Inventions, Patents, and the (Non)Collapsible Chair

UNENCUMBERED BY a centuries-old European guild tradition that limited innovation or experimentation, and fueled by a growing national market, American designers such as George Hunzinger (1835-1898) devised ingenious solutions to such perennial problems as chairs collapsing as men tilted back in them (fig. 10.27). From this American breach of manners, Hunzinger saw his marketing opportunity. Armed with another very American institution-the patent-Hunzinger created a diagonal brace used on a variety of chairs he marketed, guaranteed to withstand the rigors of the American parlor or dinner table. Patented furniture flourished in the post-Civil War decades. Folding and stacking chairs (to which Hunzinger made his own contribution), sofa beds, and extension tables all spoke to the needs of a new, more active, practical-minded public drawn to multifunctional designs for everyday living. Hunzinger's skillful use of sales agents throughout the United States, of retail marketing through mail order catalogues, and of minor design modifications targeted to different market niches, all served growing levels of consumption while maintaining high standards of workmanship. Combining the technique of interchangeable parts-chair seats or crests-with a diverse range of styles, Hunzinger accommodated the desire for individuality and product novelty while exploiting the economies of mass production. The growing design sophistication of everyday furnishings such as Hunzinger's was fueled by a happy combination of ingenious and skilled immigrants (Hunzinger was from Germany), entrepreneurial talent and marketing flexibility, and growing consumer demand.

Women Designers and Artistic Collaboration

In 1883, two years after painting his own studio (see fig. 10.4), William Merritt Chase completed a striking full-length portrait of Dora Wheeler, a former student of his, commemorating a significant moment in her life as a professional designer and painter (fig. 10.28). Here, rather than contemplating the works of the older male artist, Dora Wheeler appears as a woman of intellect and distinction. Her head thoughtfully cradled in her left hand, feet planted solidly on the ground, she stares soberly at the viewer. The portrait is a study in what were then considered daring color values-a lush, fur-trimmed at-home gown of teal blue, against a wall covering of variegated gold. The color scheme is reprised in the gorgeous teal vase with daffodils placed next to her. But while Dora is here part of an aesthetic ensemble, it is an ensemble that she herself has shaped. The portrait was painted in her studio. The daughter and partner of Candace Wheeler, a leading figure in the design world of New York City, Dora had recently been appointed chief designer in her mother's company, which produced textiles and wallpapers for the city's taste-setters. Chase used this audacious portrait to parade his sophisticated tastes and his emerging talents as a painter, but he did so with the active collaboration of his admired former student. Chase made good his tribute to the professional woman artist by opening a summer landscape school on Long Island, dedicated to training women art students, and patronized by Candace and Dora.

These two women embodied in their own successful careers the skill with which ambitious women transformed older types of feminine expression-in this case needle arts-into dynamic new forms of aesthetic entrepreneurship. In 1879, Candace joined with Louis Comfort Tiffany and two others in forming The Associated Artists (1879-83), committed to a new integrated approach to interior design in which all the elements of a room were collaboratively designed to achieve aesthetic unity. Wheeler's own company, formed in 1883 and also called Associated Artists, designed some of the most notable interiors in New York City (see fig. 10.17), with a mix of international styles, exotic materials, and sumptuous effects. Self-taught, Candace projected herself into the forefront of American design in the late nineteenth century. The domestic realm of middle-class women and their traditional needle arts proved for Candace and her daughter Dora to be a springboard to professional achievement and public recognition.

Hawai'ian Quilts and Cross-Cultural Collaborations

WOMEN 'S NEEDLE ARTS, even in the professional design world of New York, were often grounded in collaborative methods. Around the same time that the Wheelers were launching their successful business, white and Native Hawai'ian women collaborated in taking American quilt making in a new direction (fig. 10.29). Before contact with outsiders, indigenous women of Hawai'i made cloth from tree bark, which they dyed and stamped with geometric designs. Missionary women from New England began to teach quilting in Hawai'i as early as 1820, choosing women of high rank as their apprentices, an appropriate action in this status-conscious society. Although the New Englanders may not have grasped the implications of their actions, by introducing needlework to the highest-ranking women first, they ensured acceptance of quilting among all Hawai'ian women.

One distinctive Hawai'ian type is the flag quilt, demonstrating yet another use for quilts: as commemorative patriotic banners. Hawai'i's flag, adopted in 1845, is made up of eight red , white, and blue stripes, standing for the eight major islands. Where the stars in a U.S. flag would be, there is the Union Jack-the British flag-recalling the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century colonial power that preceded the U.S. government. In this quilt, four flags encircle the central applique design of the Hawaiian coat of arms. Just as Hawai'ian quilting itself was an encounter between the art forms of two cultures, so too this quilt reflects artistic collaboration between a white woman and a Native Hawai'ian woman.

The Arts and Crafts Movement

Though deeply influenced by English Arts and Crafts, the American Arts and Crafts movement incorporated national and regional influences specific to U.S. culture. Key to the Arts and Crafts philosophy was the insistence that design be tied to place, through the use of local and regional materials and forms as well as through the integration of built forms with their natural environments. In Californian architecture, for instance, the Spanish mission style furnished a regional version of rough, honest vernacular building that expressed ties to the culture of the original colonizers. In the work of the Pasadena architectural firm Greene and Greene, Japanese and Chinese elements are added as well- an influence appropriate to their location on the Pacific Rim. Greene and Greene also used the woods and stylized forms of trees native to California (figs. 10.30 and 10.31). The Greene brothers (Henry M., 1870-1954, and Charles S., 1868- 1857) served a cultured clientele-many of whom had migrated from the east- who helped nurture a local variant of Arts and Crafts, known as the ''Arroyo" style for its location alongside a steep-sided dry creek bed near the San Gabriel mountains. Here landscape, local history and influences, and patronage fused in a regional variant of the international language of Arts and Crafts.

The American Arts and Crafts movement drew inspiration from Native American as well as Asian cultures, where beautifully crafted objects played central roles in everyday life. Finding affinities with the simplified geometric designs and handmade forms of Southwest Indian design, The Craftsman and other Arts and Crafts publications of these years advocated the use of Native weavings, baskets, and pottery in domestic interiors. Pueblo pottery forms also influenced Arts and Crafts potters themselves.

Yet the Arts and Crafts return to a preindustrial form of workmanship often went hand-in-hand with a stratified commercial organization, combining master designers with skilled crafts workers, marketing and distribution departments. Though frequently associated with a single individual-Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933), for instance the products of such companies represented the work of multitudes.

Machine production put Arts and Crafts furniture within reach of the middle class by bringing down costs. Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) and Gustav Stickley (1858-1942), among others, advocated the judicious use of machine production, in tandem with handwork. The problem for them was not in machinery as such, but in the tendency to use machines merely to replicate a dead past. Instead they promoted the use of machines to spare drudgery, to act as vital servants of human creative will. Stickley, a tireless supporter of Arts and Crafts philosophy and an influential manufacturer, started out life as a stonemason, and was thus familiar with labor carried out without the assistance of machinery. Around the turn of the century, he began mass-marketing the "simple life" look of the preindustrial historical forms borrowed from the Colonial Revival and related styles. Influenced by British socialist ideals, he began publishing a magazine, The Craftsman, in 1901 to promote his ideology of simplified and honest domestic living and a restoration of the workman's control over the product of his labor. Stickley's guild organization the United Crafts was directed at bringing the designer and the fabricator-separated by industrial production-back together in one person. Yet alongside this medieval ideal, Stickley employed the most up-to-date mail order marketing, and used The Craftsman to create a national audience for his furniture. Affordable, well-made "Craftsman" furniture appealed to progressive American families who embraced the link between honest design and good citizenship.

Hand-hammered metal surfaces (usually copper or silver) were another stylistic expression of this handmade aesthetic. A pitcher by Tiffany and Company of c. 1878 (fig. 10.32) has a hammer-marked surface whose rippled effect suggests water. The pitcher also integrates Japanese influences: the design of dragonfly, water plant, and carp shows an economy of line and composition for which Japanese woodblock prints had been admired since their introduction into the West in the mid-century. The shape of the pitcher, on the other hand, derives from traditional Anglo-American sources, thus exhibiting the stylistic eclecticism characteristic of the Arts and Crafts fusion of East and West. The Tiffany Company's technical and stylistic innovations-the use of copper- and brass-colored mounts in tandem with the silver body of the piece, for instance were widely copied within an increasingly international marketplace for handmade · crafts. The aesthetic of the handmade also favored matt finishes and aged patinas over the highly glossy or shiny surfaces associated with machine production. The deliberately rough, weathered qualities of Japanese crafts carried the same appeal. Ironically, these very qualities could now be replicated through the ingenuities of American machines.

Popularized through Ladies' Home journal and elsewhere, the Arts and Crafts style emerged as a lucrative industry that reproduced the handmade "look" through machine-based or standardized forms of production. Though proclaiming the "freedom of expression" of the individual artist, Arts and Crafts products often incorporated the widespread division of labor prevalent in industry (fig. 10.33), especially as successful firms began catering to a broader market, and producing multiples from someone else's design.

The Arts and Crafts concepts of meaningful work, wholesome life, and community had a wide appeal among the American middle class. But in the context of wage labor and the growing industrial-era gap between work and home, maker and user, the movement fell well short of the significant social reforms required to realize these ideals. The high cost of handmade goods often placed them beyond the reach of ordinary families, but mass marketing through catalogues and retail brought the "look" of the preindustrial into homes throughout the nation. If Arts and Crafts itself became another style successfully marketed to sell consumer goods, it nonetheless produced a new aesthetically integrated approach to the American home and its furnishings that has remained a high point in the history of American design (fig. 10.34).

CALIFORNIA BASKETS AND THE ARTS AND CRAFTS MOVEMENT. Native American women across the continent had made baskets for several thousand years. But with the growing value placed on the handmade within the Arts and Crafts movement, Native women's basketry became weighted with new cultural meanings for American collectors. Nostalgic for a lost past, the white middle-class purchasers of such objects held romantic notions about Indians while remaining ignorant of their real lives. Discussions of basketry during the era 1890 to 1920 focused on the authenticity and anti-modernity of these objects and their makers. Yet the women who wove for what came to be called "the basketry craze" were very practical about their audience, providing wares for different price ranges, sizes, and tastes. While the California basketry trade provides one example of such interactions, similar processes occurred in the northwest and southwest regions as well.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, Pomo Indian women in the mountainous area of northern California were unsurpassed as basketmakers, this art form having been handed down from mother to daughter for at least three hundred years. When Sir Francis Drake sailed into Point Reyes, California, in 1579, a member of his expedition noted that the local baskets were "so well wrought as to hold Water. They hang pieces of Pearl shells and sometimes Links of these Chains on the Brims ... They are wrought with matted down of red Feathers in various Forms." He was referring to the renowned Pomo ceremonial basket into which were woven red woodpecker feathers. But Pomo basketry was far more varied, and characterized by fine design (fig. 10.35). Made of willow, sedge roots, and bulrushes, the design patterns were built up horizontally and diagonally around the vessel, often in complex rotational schemes. In addition to coiled and twined color patterning, surface decoration was sometimes supplemented by feathers or beads, creating a three-dimensional design effect.

The market that developed in the early twentieth century for these extraordinary baskets illustrates that two parties with different cultural concerns can nonetheless carry on profitable exchange to the benefit of both. In the market for handcrafted goods, Anglo and Native met on grounds that were more nearly equal than in any other arena. Throughout much of Native California, basketry held an important place: men caught fish in basketry traps, and women harvested wild seeds using a woven seed beater and basket. Baskets were prominent in ceremonies marking rites of passage ranging from birth, to marriage, to death. As Pomo people came into more direct contact with outsiders during the second half of the nineteenth century, the daily use of baskets declined and they were made principally for sale to outsiders; they were much in demand by collectors by about 1900. While the Pomo had always made both large and small baskets, the external market encouraged extremes. Collectors vied for the enormous and the diminutive. In fact, the tiniest Pomo baskets were so small that several could fit on a penny. In both the miniature and the gigantic, the artist pushed her technical capabilities to the maximum. Because of its large scale and elaborate design, the basket in figure 10.35 was almost certainly made on commission to a dealer or collector. Yet its maker, Sally Burris (1840-1912), was a traditional Pomo woman who had little contact with outsiders until late in her life.

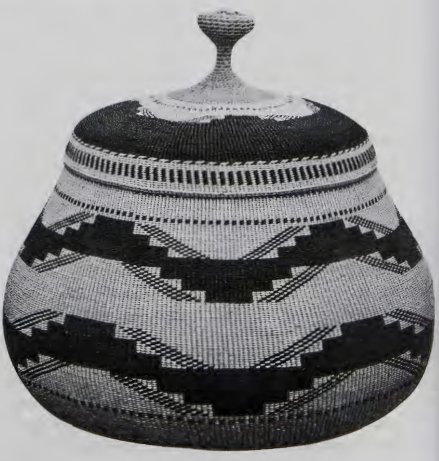

In contrast, the life and work of Elizabeth Hickox (1872- 1947) was more representative of intercultural complexities. She was a mixed-race woman of the lower Klamath River area of northern California, where Yurok, Karuk, and Hupa weavers lived, worked, and intermarried with each other and with non-Natives. As a result, their baskets often assimilated the styles of different groups. Hickox married a mixed-race businessman; the couple owned cars and radios, and traveled. Regarded as the finest weaver in her region, she specialized in globular baskets with lids (fig. 10.36). For many years she was under exclusive contract to Grace Nicholson, a wealthy California dealer who guaranteed her an annual income of $500 so that she could devote herself to her craft. Nicholson lived in Pasadena, the epicenter of the Arts and Crafts movement in the West.

She transformed the first floor of her spacious home into a gallery (fig. 10.37) stuffed with textiles, baskets, and other Native objects. For most of the first quarter of the twentieth century, she sold such items to wealthy collectors, including women who eagerly sought Native women's artwork to adorn their own domestic interiors. In this instance, Nicholson promoted Elizabeth Hickox as a marketable commodity during an era when Americans were increasingly focused on name recognition and brand recognition in many aspects of their daily lives.

Hickox won individual recognition for her work, living comfortably between cultures. Paradoxically, her patrons believed they were investing in an authentic "premodern" work of Native craft that they alone valued as art. Each side in this exchange had its own objectives, each reconfirming identities through exchange. Hickox, far from being "contaminated" by contact with the market, used Nicholson's patronage to advance her most original designs. At a time when other forces were fragmenting Native lives and craft practices, the basketry trade promoted cultural survival. Having a patron who bought everything she made allowed Hickox to continue to create unique baskets-some woven with more than 800 stitches per square inch-at a time when nothing in her local culture rewarded such painstaking artistry. Elizabeth Hickox is an example of a Native artist who negotiated the opportunities of the market to nurture her own craft and to move fluidly between Native and European societies. In the marketplace of style, Native Californians recovered some of the agency and independence they had lost with the imposition of the mission system in the eighteenth century.

TIFFANY, AMERICAN INDIAN BASKETRY DESIGN, AND THE 1900 PARIS EXPOSITION. 1900 was a year of unparalleled prosperity for American elites. Nowhere was America's wealth demonstrated with greater opulence than at Tiffany and Company's exhibit at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. The head of Tiffany's Art Department, Paulding Farnham (1859-1927), chose to display items that, in materials and imagery, represented all North America. From jewelry set with Mexican opals and Montana sapphires, to silver bowls based on Native American basketry and pottery and set with Arizona turquoise (fig. 10.38), the splendor and originality of American design was on display. Farnham had created jewelry and bowls based on Native designs for Tiffany's exhibits at the Paris Exposition of 1890 and the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, but the designs for 1900 were particularly bold, and won numerous medals.

This vessel, formed of silver, beaten copper, and turquoise, demonstrates how indigenous design became part of the universal vocabulary of design reform at the turn of the century. It is based on a late-nineteenth-century Hupa basket from northern California. To the ordinary viewer at the exposition, much of the delight in this object may have been in the apparent contradiction seen in the transformation of a vernacular object made of humble materials (the basket) into an opulent object of semiprecious materials. Yet the basket, transformed into a luxury object by the creativity of Tiffany's designers, itself represented the highest standards of Native craftsmanship. The form adopted by Tiffany was already an object of intercultural commerce, made expressly for a high-end market and conferring status on its maker, as we have seen in the example of Elizabeth Hickox's basket, above.

Awakening the Senses: The Glasswork of Tiffany and Company and John La Farge

The decorative arts were an area not only of technical and design innovation but also of exploration into the purely sensuous properties of materials. The most advanced expression of this interest concerned stained and blown glass. It is fitting that the two most innovative designers in this area were men who had distinguished themselves in numerous other media as well. Louis Comfort Tiffany crossed the boundaries separating art from craft and painting from decoration. He produced easel paintings, but also worked in metal, mosaics, and glass, introducing rich textures, pattern, and color into unified aesthetic environments. John La Farge was a painter and watercolorist, precociously interested in the optical effects of light and color on the perception of form, before becoming interested in stained glass. Both men embraced "eye appeal" and the affective power of rich, deep color as a foundational element of design. As Tiffany explained years later, "The sovereign importance of Color is only beginning to be realized in modern times .... These light vibrations have a subjective power and affect the mind and soul, producing feelings and ideas of their own."20 Tiffany credited a trip to Egypt and North Africa with awakening his passion for color: "I returned to New York," he later wrote, "wondering why we made so little use of our eyes."21

Both an artist and a businessman who ran one of the most successful companies in the history of American decorative arts, Tiffany made technical innovations that, in tandem with his marketing genius, were widely adopted. An avid traveler, he used his curiosity about other cultures and traditions-from Japan and China to Egypt, the Middle East, India, classical Greece, and Native America; and from Byzantine mosaics to Venetian glass-to fuel his visual imagination. Driving his creativity was a passion for color and light. These two concerns-grounded in the sensory apparatus of the body itself-increasingly characterized many aspects of late-nineteenth-century art. Tiffany's importance extends far beyond the leaded glass lamps, endlessly imitated, for which he is best known. He mastered a number of media (painting and watercolor, ceramic, glass and stained glass, mosaic, and metal) in an era that saw its share of "multimedia" artists. His company won international fame not simply for the extraordinary quality and beauty of its work but for combining handcraft methods with an industrial scale of production and marketing.

In 1893 Tiffany developed a technique known as favrile (see fig. 10.1) in which pigments were swirled into molten glass, making color integral with the glass body, and fusing form and surface in a spectacular harmony. Glass was the very embodiment of colored light, and Tiffany exploited its translucency and its fluid nature to the fullest, with swelling forms gracefully contracting to narrow openings, flaring out and pulled tautly slender. Tiffany handled these materials with a new freedom, technical innovation, and appreciation for the abstract qualities of light and color that suggest the first stirrings of a modernist sensibility.

Along with his cosmopolitan influences, Tiffany drew from the imagery of a fecund and vital organic world, fitting comfortably within an American context while making its own unique contribution to the international language of Art Nouveau: the "new art" whose swirling, attenuated, and asymmetrical forms found their way into the visual and decorative arts of America and Europe around the turn of the century. The fluid shapes of favrile glass, along with its surface designs, suggest sea forms and flowers, while its iridescent colors recall exotic birds.

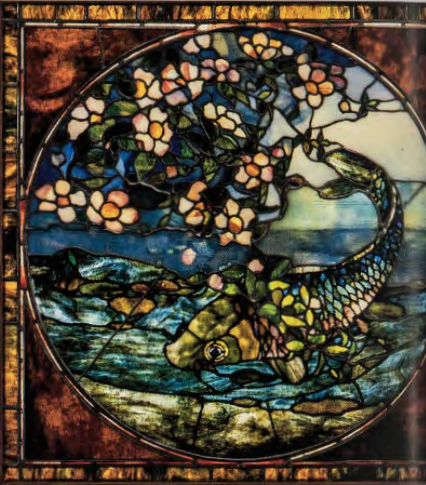

Stained glass was an important area of innovation in American design of the late nineteenth century, for both Tiffany and La Farge. John La Farge described stained glass window decoration as "the art of painting in air with a material carrying colored light."22 Competing for new effects that would express the beauty of colored glass, both artists embarked on a restless search for new techniques that brought them leading commissions and international fame (La Farge received a Legion of Honor decoration from the French government). Their list of patrons was a Who's Who of American business and industry, from]. P. Morgan to the Vanderbilts. The art of stained glass had changed little since its height in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Extending the possibilities of colored light into this medium, both artists developed parallel methods for achieving layered depths of modulated color, and new effects of shading and variegated hue that approximated the complex colors of nature. Both men used a vastly expanded array of colored glass, newly available through industrial methods, blended together to suggest depth and subtlety. Their techniques included incorporating opalescent glass, floating small bits of colored glass between layers (known as confetti), swirling molten glass to achieve rippled textures, and using the leading between the glass as a decorative element in the composition (fig. 10.39). They eliminated techniques that detracted from translucency- such as the medieval technique of painting in details- and they exploited random variations in color density and range to achieve painterly effects. La Farge's sources ranged from Japanese woodblock prints to Chinese Ming Dynasty painting and the monumental figural art of the Italian Renaissance. Flooded with sunlight, the stained glass of La Farge and Tiffany achieved-in the words of one European admirer-an "astonishing brilliance," unrivaled by any other art form.23