9.4: The Clash of Cultures, From Both Sides

- Page ID

- 215493

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Plains Indian people presented their own views of their culture and history in art during the same decades that they were so widely represented by white artists. Theirs is a story of displacement by post-war white expansion. Chronicle, commemoration, loss, witness, and removal from history, all play a role in their story, as told by both sides.

The year 1876-that of the Philadelphia Centennial marked both celebration (the republic was one hundred years old) and setback (the defeat of George Armstrong Custer by Plains warriors just a few months into the great national birthday celebration). "Custer's Last Stand" became a symbol of the nation beset by hostile Indians, immigrant anarchists, and striking workingmen, common enemies of the republic's westward progress and industrial expansion. The Plains Indian wars-of which the Battle of Little Big Horn was but one episode-concluded in 1890 when federal troops massacred 146 Lakota men, women, and children at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Methodically deprived of their way of life and confined to the reservations, Plains Indians would no longer threaten western settlement. For older Native Plains cultures, this was a time to commemorate the losses that accompanied forced assimilation and displacement.

Plains Ledger Drawings: Native Commemoration in an Era of Change

In the years around the Centennial, white Americans were not alone in looking to the past. For Plains cultures at war with the U.S. army this era was shrouded by an atmosphere of crisis and loss. Their treaty rights ignored, their ancestral lands invaded and exploited, their hunting grounds diminished, their dignity in question, Plains artists seized a new medium-drawing on paper-to commemorate a disappearing way of life, recording traditional scenes of armed combat and horse capture. They also chronicled their painfully changing circumstances, situated between worlds. Although white and Indian shared an impulse toward recollection and commemoration, they did so under radically different conditions. Confronting modernization, white Americans indulged in wistful fantasies of a simpler time; for Plains peoples, facing a loss of their way of life through forced removal and confinement, the ability to recollect and express spiritual meaning and personal accomplishment was a matter of survival.

Plains artists eagerly adopted the paper and pens provided by traders and explorers early in the century and by military men and Indian agents later on. Often the paper they drew on was discarded from lined account books, or ledgers, hence the name "ledger drawings." In other instances, they were given artists' notebooks or small writing tablets. Ledger drawings miniaturized the imagery painted on the much larger hide robes. In some instances, men carried their small books of autobiographical pictures into battle; such books were among the plunder taken by army soldiers from dead braves on the battlefield. In other instances, drawings were readily sold or exchanged as gifts with whites. From 1865 to 1890, Plains artists made thousands of these drawings, many of which still exist in museums and historical societies, though a few remain in Native hands.

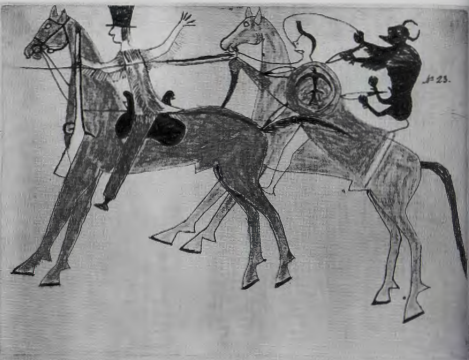

SITTING BULL'S EXPLOITS AS DEPICTED BY FOUR HORNS. While men most often depicted their own exploits, occasionally they might also record the brave deeds of a relative. In 1870, Four Horns, by then one of the most respected chiefs of the Hunkpapa band of the Lakota, drew fifty-five images of his nephew Sitting Bull's war record (fig. 9.35). In order to make clear that he was not claiming these deeds as his own, but simply recording his illustrious nephew's accomplishments, Four Horns drew an extra-large name glyph-a sitting bull-behind the horseman on the right, and connected it to his face by a line. (A knowledgeable Lakota examining the drawing would also recognize the raptorial bird on the shield as Sitting Bull's distinctive emblem.) Sitting Bull's victim is a frontiersman in a buckskin jacket. While facial features were unimportant to the artist, Four Horns carefully rendered the flintlock rifle, saddle, war shield, and name glyph with great accuracy. While it was not uncommon for a fine draftsman to be commissioned to draw the exploits of a comrade, it may be that Four Horns was documenting Sitting Bull's bravery and generosity to promote his nephew for the new role of paramount chief, who would speak for all the Sioux.

These drawings not only provide a record of one man's career, but also reveal the pride an elderly uncle took in the successes of his beloved nephew. Sitting Bull earned his first war honor at the age of fourteen. By 1870 he and his uncle had traveled on many war parties together, captured many horses, and fought many Crow enemies. An army doctor,James Kimball, bought fifty-five drawings of Sitting Bull's life from Four Horns in 1870 at Fort Buford in Dakota Territory. Eleven years later, the illustrious chief Sitting Bull, who had taken his followers to Canada rather than submit to reservation life, surrendered to the U.S. army at the same fort.

PRISON DRAWINGS FROM FORT MARION. In 1875, several dozen Kiowa and Cheyenne men, accused of crimes against white settlers in "Indian Territory" (present day Oklahoma), were incarcerated for three years at Fort Marion, formerly the Spanish Castillo San Marcos, in St. Augustine, Florida (see fig. 3.22). In an unusual experiment, their jailer, Lieutenant Richard Pratt (who later became the head of the first Indian boarding school), gave these prisoners drawing supplies and encouraged them to make drawings to sell to the tourists who frequented this seaside resort, as well as to influential reformers such as the novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Episcopal Bishop Henry Whipple, who visited the men at what was considered to be a model prison.

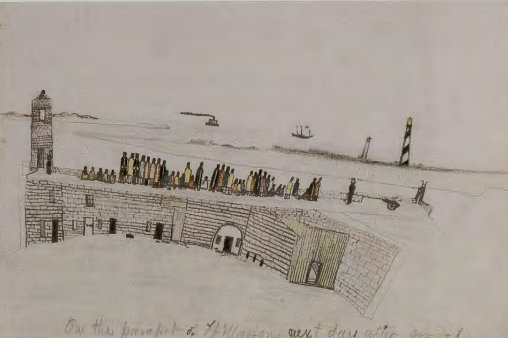

The artists at Fort Marion recorded scenes of warfare and the hunt, common in the Plains pictorial tradition, but they also added scenes from their new experiences as warriors who had been transported by train and paddle-wheel steamer far from their prairie homes. The Kiowa artist Zotom (1853-1913), for example, drew a scene of the prisoners standing on the parapet of the massive stone fort, the day after they arrived in humid St. Augustine (fig. 9.36). They stare out at the harbor lighthouse and ocean beyonda vista far from home. Though each figure is tiny, and all face away from us, Zotom makes the viewer confront the grim realities of displacement, and the poignant despair of those who have been torn from the fabric of their culture.

With access in prison to chromolithographs, newspapers, and photographs, Zotom and some of the other warrior-artists mastered the rudiments of perspective, depth, and foreshortening. Their works stand somewhere between the flat pictorial depictions of their forebears on the Great Plains, and the complex perspectival spaces of nineteenth-century painters. In .this drawing, Zotom depicts a heart-rending moment: the prisoners have not yet been stripped of their traditional blankets and leggings and forced to wear army garb; yet their fate as captives in hostile territory is painfully clear.

Zotom's life story exemplifies the complexity of Native experience between cultures at the end of the nineteenth century. Raised as a traditional warrior, he converted to Christianity during his imprisonment in Florida. After his release in 1878, he trained as a deacon in the Episcopal Church in New York. Finally, after some years of preaching Christianity in Indian Territory, he renounced his ministry and returned to traditional Kiowa spirituality.

WOHAW IN TWO WORLDS. Another artist-prisoner at Fort Marion stands alone among Plains graphic artists of his generation in his remarkable fusion of reality and metaphor in Wohaw Between Two Worlds (fig. 9.37). In a poignant expression of Native ambivalence at being trapped between two incompatible ways of life, Wohaw (1855-1924) depicts himself extending a peace pipe to symbols of both realms: the wild buffalo and tipi of traditional Kiowa life, and the domesticated steer, plank house, and plowed field of the western settler. The sun, crescent moon, and falling star look on in mute witness to this moment of historical transition. Wohaw uses one figure-himself-to depict the plight of all Indian people in the last third of the nineteenth century. Indeed, the metaphor of "standing with a foot in two worlds" is still invoked by Native artists (see fig. 18.24: T. C. Cannon, "the Collector"). Wohaw's drawing-while presenting loss-locates the artist at the center of the encounter and the conflict between cultures, trying to make peace with both.

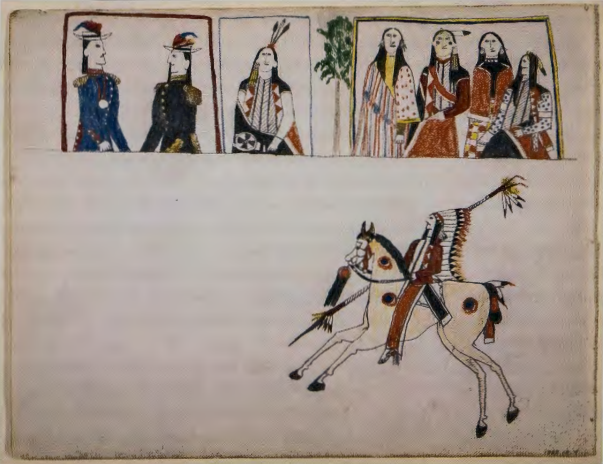

Wohaw juxtaposes the expressive modes of two different cultures in another unusual composition in which a warrior on horseback looks up at three portrait images of Kiowa people (fig. 9.38). The framed portraits, with their stiff frontal and three-quarter views, derive from the conventions of portrait photography, a genre familiar on the Great Plains by the 1870s. The formal photographic portrait was also familiar to the prisoners at Fort Marion, for they posed for such portraits, and the photographic process was an occasional subject of their drawings. The double image of the Indian, in both indigenous and western garb, was a standard trope of late-nineteenth-century photographic portraiture, suggesting to the white viewer of the time the uplifting effect of "civilization." To the Native artist and audience, however, such imagery may have held a different meaning.

The men at the upper left wear plumed U.S. cavalry dress hats and officers' fancy-dress frock coats, complete with shoulder insignia and gilt buttons. One prominently displays his peace medal, suggesting he is a man of social stature. The figures in the other portraits, both male and female, wear equivalent Kiowa finery: breastplates made of bone pipes, fine cloth blankets with beaded rosettes, and dresses of patterned trade cloth. Negotiating between two worlds, the artist may be playing with the idea of cultural equivalence, equating U.S. military and Kiowa formal dress. Below, the Kiowa equestrian also wears his sartorial best: the eagle-feather war bonnet is among the most impressive items of Plains ceremonial regalia.

BLACK HAWK'S VISION OF A THUNDER BEING. While captive Kiowa and Cheyenne artists at Fort Marion were chronicling new themes, graphic artists on the reservation also depicted both traditional and innovative imagery. In 1880, a Lakota holy man and artist named Black Hawk ( c. 1831- c. 1890 ), who lived on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, made seventy-six drawings encompassing a wide view of the Lakota world. Unlike some of his contemporaries, he seems deliberately to have avoided drawing scenes of white men, though some of his drawings depict their imported goods, such as trade cloth and guns. Black Hawk's spiritual power came from his potent visionary experiences.

In a picture captioned "Dream or vision of himself changed to a destroyer and riding a buffalo eagle" (fig. 9.39), Black Hawk sought to convey what was surely one of the most sacred moments of his life. His composition is based on the image of a horse and rider-a ubiquitous theme in Plains iconography. Yet the steed and rider are anything but ordinary. Their extremities have been transformed into eagle talons, and buffalo horns curve from their heads. The intensity of the rider's clenched teeth in his round head is enhanced by his mesmerizing yellow eyes. Both figures are covered with small dots, representing hail, and are connected by lines of energy radiating between the rider's talons and the animal's mouth. Horse and rider fly though the sky, encircled by a rainbow formed from the beast's multicolored tail.

While Black Hawk called this a "destroyer," it clearly represents a Thunder Being-a powerful supernatural creature said to appear to supplicants in vision quests. Depictions and descriptions of Thunder Beings often combine attributes of eagle, horse, and buffalo, all sacred animals. The rainbow, too, is not only an entrance to the spirit world, but a symbol of Thunder Beings. Various descriptions of Thunder Beings emphasize their powerful eyes. Another Lakota holy man, Black Elk, who saw these creatures in his own visions, commented that every time the beast snorted, "there was a flash of lightning and his eyes were bright as stars." When men performed public dances impersonating such figures, their black-horned head coverings had mirrors where the eyes should be, in order to flash and glitter in the same manner as these lightning-eyed spirit beings. The bringers of summer's powerful electrical storms, Thunder Beings are the sacred embodiment of thunder, lightning, wind, and hail.

The Noble Indian and the "Vanishing Race.'' Once Again

If Wohaw placed himself at the center of historical change in the decades surrounding the Centennial, eastern artists in these same years consigned Indians to noble defeat at the margins of history, reinforcing the widely held idea that they no longer possessed any cultural existence. White artists memorialized a "dying" culture whose tragic fate was sealed by the inevitability of continental empire. In photography, painting, and popular imagery the idealized figure of the Native American consistently appeared in a posture of defeat. Measured against the standards of "civilization," Native cultures appeared maladapted, backward, disadvantaged by history itself.

THE END OF THE TRAIL. This sculpture by James Earl Fraser (1876- 1953) (fig. 9.40) was first modeled in 1894 and exhibited in a monumental version at the San Francisco Panama Pacific Exposition of 1915. Fraser's statue took its inspiration from the poet Marion Manville Pope: "The trail is lost, the path is hid and winds that blow from out the ages sweep me on to that chill borderland where Time's spent sands engulf lost peoples and lost trails." A mounted Plains Indian slumps over, the lines of his body mimicking those of his steed, whose bowed neck, closed eyes, tail between legs, and hooves meeting on a contracted point of land, all signify defeat. The downward-pointed spear suggests a cessation of hostilities, defeated manhood, and a draining of virile energies. Fraser's treatment of the conquered recalls the defeated barbarians subdued by the Roman empire. Raised in South Dakota, and having seen at firsthand the demoralizing effects of the reservation, Fraser sympathized with the Indians' plight.

THE DAWES ACT. In 1887, the federal government passed the Dawes Act, which subdivided communal reservation lands into individual allotments, enforcing an agricultural order on western Indians. Federal policy toward American Indians was directed at the systematic eradication of Native languages, dress, and ritual life- all those things that tied Native Americans to their own past, obstructing the process of willed assimilation that was the official intention of the government. "We must kill the Indian in order to save the man," as Richard Pratt, the jailor of the Fort Marion prisoner-artists, put it. Pratt went on to found the Carlisle School, the first in a network of "Indian schools" that endeavored to turn Indians into good citizens and workers.

THE SONG OF THE TALKING WIRE. Contemporary audiences understood the defeat of the Indian as the inevitable triumph of a technologically and culturally superior nation over a backward race. The evidence was there in the establishment of a nationwide industrial system connecting space by railroad and telegraph. Henry Farny's (1847-1916) The Song of the Talking Wire of 1904 (fig. 9.41) examines the clash of cultures as an aging Indian brave, wrapped in a buffalo robe and cradling a gun in his arm, encounters a voiceless technology. Leaning against a telegraph pole, he strains to hear the mysterious codes transmitted along the lines-an image of two cultures unable to communicate. Pictured against a bleak wintry landscape, the old man gazes toward the viewer with a pained expression. To the left of the telegraph poles is a buffalo skull, a memento mori marking the demise of the animal on which Plains cultures depended for survival. Like the earlier expressions of the "vanishing American" theme, these later works mingle regret over the plight of Native people in an era of technological progress with a sense of fatalism regarding their inability to adapt to the direction of history.

The Past as Spectacle: Buffalo Bill Cody's "Wild West"

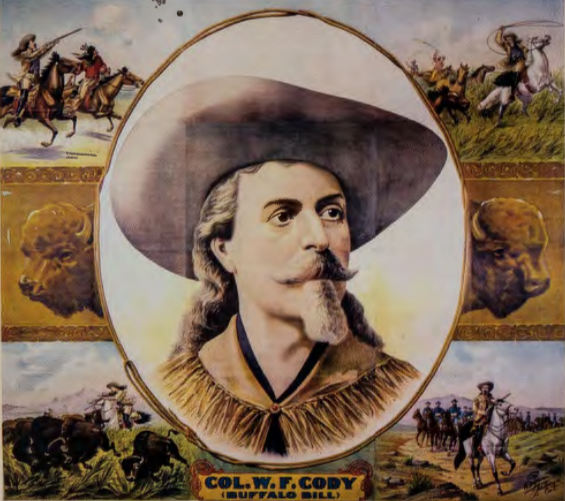

FROM 1883 TO 1916, William F. Cody ("Buffalo Bill") thrilled audiences throughout the United States and Europe with his "Wild West," a heart-pounding spectacle combining live animals and human performers who restaged the life and times of the Old West (fig. 9.42). Scholars such as Joy Kasson see in Buffalo Bill's "Wild West" the birth of mass entertainment and of a media culture that blurred the differences between history and spectacle, truth and fiction . Despite its claims to present the real history of the conquest and settlement of the frontier, the "Wild West" offered a fictional version of the past as it lived on in the popular imagination, conflating history with public myths about the progressive unfolding of American civilization across the continent. Later generations recoiled at the underlying violence that lay at the heart of the spectacle of Buffalo Bill. Yet this exhibition of manly prowess, adventure, and death-defying courage left its imprint on twentieth-century images of the frontier, from the movie Western to the "tall in the saddle" style of American diplomacy.

Buffalo Bill , however, saw the "Wild West" not as entertainment but as education for a public eager to know "how the West was won." In 1886, the "Wild West" began reenacting Custer's Last Stand by situating it within a historical context of preordained triumph. Year after year, as it toured throughout Europe and the United States, the "Wild West" dramatized, in the words of the cultural historian Richard Slotkin, "the principle that violence and savage war were the necessary instruments of American progress." 11

Blurring the line between history and myth even further, Indian warriors at the forefront of the Plains wars such as Sitting Bull were later recruited to be part of the "Wild West." While it is tempting to view this as an example of Native peoples being manipulated for economic gain, each Native participant made something different out of the experience. Some returned to reservation life with substantial amounts of cash for their families. Sitting Bull, shocked at the sight of homeless children begging in the heart of New York City, distributed most of his earnings to these children, as any honorable Lakota would do. The famous Lakota holy man Black Elk, who as a young man went to Europe in the 1880s as part of Buffalo Bill's entourage, revealed his hope of learning some secrets of the white man that would help his people.

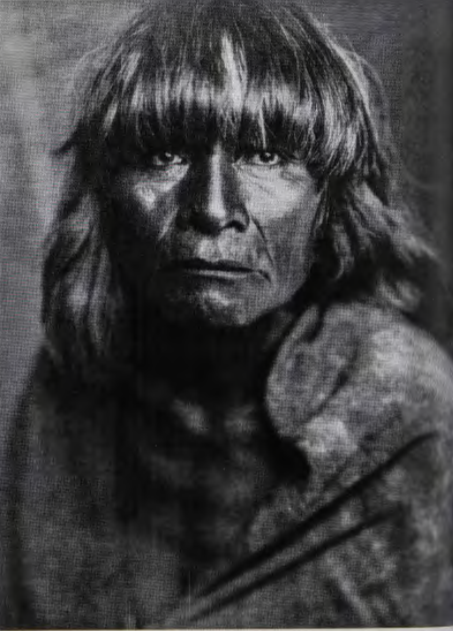

THE NORTH AMERICAN IND/AN BY EDWARD CURTIS. Beginning in the Centennial years, the new technology of the camera was put to the service of documenting Indian culture. Over a quarter-century after the Centennial, the photographer Edward Curtis began a project that would eventually become his twenty-volume The North American Indian. Begun in 1907 and completed in 1930, nearly a century after Catlin, The North American Indian resembled the earlier artist's project in many respects. Compelled by a desire to preserve in photographs the threatened traditions, knowledge, and sacred rites of Native people throughout the West, Curtis devoted his life to completing this vast project, comprised of some twenty-two hundred photoengravings (photogravures) taken from eighty Indian nations (fig. 9.43). Earning the trust of sympathetic elders and medicine men through "weeks of patient endeavor," in his words, he also won the support of some of the wealthiest men in America, including]. P. Morgan.

The North American Indian surveyed Native peoples at a time when they were living on reservations and struggling to maintain their ceremonial life and art forms. In many cases- as for instance in his images of Plains war parties- Curtis asked his subjects to reenact traditional cultural practices. Like Catlin one hundred years earlier, Curtis wished to preserve the image of Native culture in a pristine condition, as he imagined it, prior to clocks, blue jeans, generators, and sewing machines. The velvety chiaroscuro of his portraits suggests a world already transformed into art. Curtis's work shared in the pictorialist aesthetics of his generation, aesthetics that distanced his subjects from the present. He saw his project as a form of what is called today "salvage anthropology" - involving the collection and cataloguing of detailed observations about everything from music, dance, and dress, to food preparation, language, religion, and burial customs-an archive of knowledge that framed the individual Indian subject.

From the beginning, Native people had viewed photography warily. Was the photographer robbing Native subjects of their inner lives by pinioning them to a photographic archive, or did the camera capture the fleeting spirit on film? The photographic image, associated with death and memorialization from the mid-nineteenth century on, helped entrench the idea that Native societies were threatened with extinction. On the other hand, photography also served N ative cultures' desires for images of their traditions. Native Americans themselves used the camera for purposes of self-documentation. Each party to the photographic encounter played an active role.

In meticulously documenting reenactments of vanishing ways, Curtis furnished what proved to be a vital record, enriching cultural memory for later generations of Indians. George P. Horse Capture, for example, first came across his great-grandfather, a Gros Ventre tribal leader from Montana, in 1969, through a Curtis photograph he was shown in a historical archive. Seeing Curtis's photograph of the tribal elder launched his great-grandson on a journey into tribal history and identity.

"ALASKA VIEWS." Unlike Curtis, who staged idealized portrayals of the "vanishing" American Indian, some photographers matter-of-factly recorded the changing realities of life in turn-of-the-century Native America. Lloyd Winter and E. Percy Pond were commercial photographers who operated a studio in Juneau, Alaska , from 1893 to 1943. Both were from San Francisco, where Winter had studied art at the California School of Design. In Alaska they provided the burgeoning tourist trade with images of: Alaska Views. Choicest and largest collection of Views of Alaska Scenery, comprising illustrations of Indian Life, Totems, Glaciers, Seal Islands, Mines, Yukon, Sitka, Juneau, Wrangel, and other Points of Interest in Alaska," as they advertised in an Alaskan newspaper in 1894.

Winter and Pond used dry glass-plate negatives, a technological improvement over the previous generation's wet-plate negatives, which had to be developed immediately after exposure. This made working in remote areas an easier proposition. In bracing contrast to Curtis's romanticism, Winter and Pond documented the bustling commercialism and the hybrid nature of turn-of-the-century Alaskan villages. In their work, ceremonial regalia exists comfortably alongside tailored shirts and suspenders (see fig. 7.22, Interior of Whale House of Raven Clan), and Tlingit mortuary poles stand proudly in front of a chiefs modern frame house with glass windows (fig. 9.44).