9.2: Facing Off- Divided Loyalties

- Page ID

- 215491

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

In the years surrounding the Centennial, images of feathered Indians and shaggy buffalo appeared widely, on decorative items such as silver punch bowls and porcelain vases as well as in paintings and prints. Once symbols of America's difference from Europe, American Indians now served as decorative icons of the nation's growing imperial control over the continent. Karl Mueller's porcelain Century Vase (fig. 9.13), exhibited at the Centennial Fair, fuses the Indian chieftain, the buffalo head, and the spread eagle-complete with jagged thunderbolts recalling stylized Native American forms-into a composition centered on the portrait bust of the founding father, George Washington. Vignettes of telegraph poles and factories alternate with Western wildlife: grizzly bear, wolf, and buffalo, along with scenes commemorating the origins of the republic. The technological future and the heroic past fuse seamlessly.

The Century Vase encapsulates the cultural contradictions of the fair itself. Throughout the great halls of the Centennial exposition, the past- as colonial history and as savage frontier- was displayed alongside industrial machinery announcing the triumph of technology over nature. Looking backward and forward, the fair offered little contemplation of the present; its vast spectacle conveniently overlooked the Plains wars, the failures of Reconstruction, and the birth pains of a new industrial order.

Compositional and Thematic Polarity

While the displays of the 1876 fair may have been refashioning the past to announce a triumphant technological future, the strains of modernization were becoming evident nonetheless. Compositional and thematic polarities observable in some thoughtful artworks of the period embody the characteristic divisions around which rural and industrial, elite and democratizing forces confronted each other in the years around 1876.

THE MORNING BELL. Painted prior to his trip south after the Civil War, Winslow Homer's The Morning Bell of 1866 (fig. 9.14) focuses not on the divisions between the North and the South but on those internal to an industrializing society. The painting plays on the contrast between the bucolic world it depicts and a new industrial order, advancing upon it as steadily as the lone woman crossing the bridge. The Morning Bell is composed around two primary axes that intersect in the figure of the lone woman. The bridge and the three women on the right define a horizontal axis. What begins on the right as open space grows increasingly claustrophobic as we travel leftward toward the darker mill building with its bell tolling the new rhythms of industrial life. By contrast, the vertical axis defined by the rickety side bridge- opens toward the forest and sky, culminating in a lone bird soaring above the treetops, a distant symbol of flight and freedom. The woman crossing the bridge stands midway in transition, from right to left, vertical to horizontal, and rural to industrial. The wildflowers, dappled sunlight, and distant cabin recall a rural world of homespun clothing, like that worn by the three bonneted girls who gossip about the arrival of the fashionably dressed young woman. Her clothes, by contrast, are a product of the textile mills and ready-to-wear clothing industry that changed the look of the nation in the years after the Civil War.

In its spatial and narrative organization, The Morning Bell opposes the rural basis of national life before the war, rooted in natural time, with an emergent order of regulated labor; the isolated figure of the female laborer contrasts with the communal world of the three farm girls, who also now work in a factory. The tree on the left, which literally anchors the bridge, has been symbolically sawn and planed to furnish the planks out of which the bridge is constructed. Homer's painting makes a piercing comment on the inadequacy of antebellum values within a post-Civil War society. The New England countryside in the painting mirrors the popular imagination of rural peace, but it harbors within itself a deeper change, a slow, step-by-step movement into a world of industry and mechanization that spells the end of that once idyllic dream.

The Persistence of the Past: The Colonial Revival

Despite the tendency of Americans to invoke divine authority to sanctify their ambitions, the Civil War had exposed the all-too-human fallibility of the fragile social covenant. Adding to the strains were the political scandals and partisanship of the Gilded Age, as well as the greed unleashed as new territories were opened to commercial exploitation. As time and events distanced the nation from its founding, the generation of 1876 desired reassurance that core values had not changed, that America remained culturally homogeneous and connected to a past at once heroic and humble.

For visitors, the Centennial Fair offered a sentimental journey into history. Nostalgia-the longing for home, for the past-set the tone for much of the art made in these years, symptomatic of a generation searching for emotional ties to a past being increasingly pushed aside by change. This period occasioned a time of national introspection, of yearning for artisanal labor, rural childhood, and village scenes. Such subjects carried national memory past the carnage of the Civil War to a period before the birth-pangs of industrial democracy. Architects, designers, artists, and illustrators sought inspiration from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, times of chaste restraint, homely simplicity, and moral rectitude. Yet this so-called "Colonial Revival" went hand in hand with a vision of America as a nation at the forefront of progress. The Philadelphia Fair displayed the contradictions inherent· in this combination.

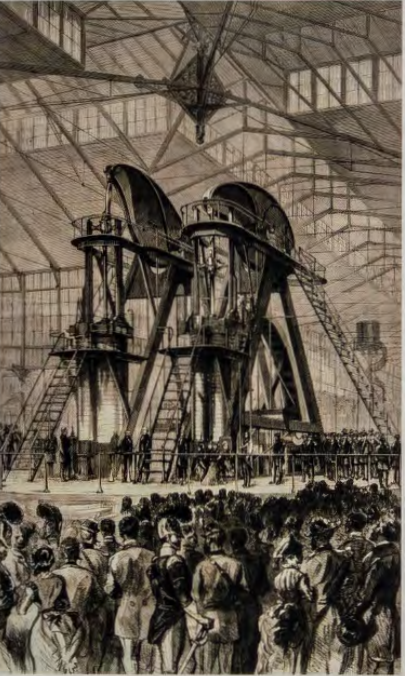

At the symbolic center of the Philadelphia fairgrounds towered the giant Corliss engine, a turbine that powered the 450 acres of exhibits. A Centennial print (fig. 9.15) shows President Ulysses S. Grant inaugurating the fair by firing up the Corliss, in the company of visiting dignitaries from Brazil. Locked into place by stairs leading to high platforms, the engine seems a Frankenstein monster of technology tamed for social purposes, and a proud symbol of the new nation whose birthday is being celebrated.

The presence of the Corliss engine at the fair points to a redirection of America's sense of nationhood from nature to technology. Mechanization created new unities of time and space; telegraphs, railroads, and standardized time zones spanned the enormous distances that had once separated Americans from one another, and these connections diminished the provincial and local character of American life. Yet at fair exhibits, visitors could return to the colonial and frontier eras of American history. While putting technology on display, the fair also celebrated preindustrial time.

The Colonial Revival focused national identity on New England origins. Seeing "New Englandly," in the poet Emily Dickinson's words, became a national habit, as Americans from different regions and ethnic backgrounds imagined a past of white clapboard houses and manicured greens, remote from immigration, cities, and industry. This image of the New England village was itself an invention of the Colonial Revival; historically, the greens had been muddy commons, and houses of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were not painted white.

The themes of Colonial Revival were taken up by a range of painters, sculptors, printmakers, photographers, designers, and architects in the decades following 1876. Increasingly, as the urban upper class consolidated its financial and commercial power, it turned to genealogical societies, American antiques, and crafts such as needlework to ground its activities in a comfortingly stable and unified past.

THE PURITAN. Augustus Saint-Gaudens's The Puri.tan of 1887 (fig. 9.16) is both tribute and parody. It was commissioned at a time when America was besieged by moral backsliding at every turn: public graft, prostitution, and self-serving behavior. The Puritan strides toward us with a summons to self-examination, recalling viewers to the memory of Old New England as the symbolic heart of the republic. Yet Saint-Gaudens's grimfaced, Bible-toting Pilgrim Father possesses a rectitude that borders on rigidity and tramples on the delicate foliage underfoot. Dead set on the straight and narrow, the Puritan would come to be reviled as the zealous, provincial, and joyless type of American.

Of French and Irish ancestry, Saint-Gaudens did not share unequivocally in the myth of the nation's Puritan and Anglo-Saxon origins. Colonial themes in painting and book illustration, house design, and consumer culture, however, maintained a persistent place in the lives of affluent Americans. These themes offered what the architectural historian Dell Upton has called an "ancestral homeland" in the form of Windsor chairs and spinning wheels as well as suburban house types from the Tudor to the Cape Cod and Georgian. All offered instant "tradition."

THE SHINGLE STYLE. Seventeenth-century New England houses also helped inspire the so-called "Shingle Style," one of the first distinctly national design idioms, and an American version of an international movement that grounded domestic architecture in vernacular forms and materials. Designers such as Charles McKim (1847- 1909) (fig. 9.17), H . H. Richardson (1838-86), and Stanford White (1853- 1906) were all enthusiasts of the Shingle Style, finding inspiration in such colonial predecessors as the Fairbanks house (see fig. 3.29 ), with its irregular profile, multiple dormers and gables, and shingle sheathing. The additive qualities of seventeenth-century houses- in which rooms were built onto the main structure over generations- were an architectural symbol for generational continuity and the seamless presence of the past. Interior plans were open and relaxed, with large, non-axial room arrangements. An idiom particularly favored by older monied families in New England, but which eventually spread throughout the United States, the Shingle Style avoided antiquarianism, splicing Japanese and medieval influences onto more local sources, and combining American origins with such up-to-date amenities as wrap-around porches, elaborate wall paneling, and built-in sideboards.

QUAINT, ENDEARING, AND COMFORTING. By 1876, needlework samplers were considered a quaint reminder of early America. They began to be collected and prized as museum specimens. The Leverett sisters' embroidered chest of the 1670s (see fig. 3.34) was displayed at the "Exhibition of Antique Relics" at the Centennial.

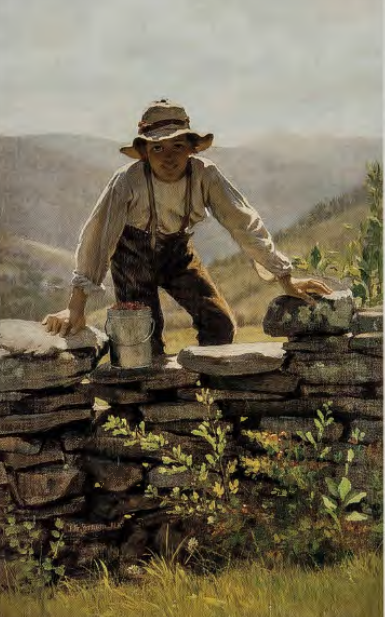

The Centennial' s backward glance also fastened on images of rural childhood given currency in Mark Twain's The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, the eponymous hero of which is only the best known of a troupe of endearingly naughty ragamuffins who resisted the discipline of bath, school, and church. The Berry Boy (fig. 9.18) by J. G. Brown (1831-1918) reinforced a popular mythology about the wholesome rural origins of the urban entrepreneur, a training ground for the resourceful independence required to succeed in the business world of post-war America. With his direct, wide-eyed gaze and plucky appearance, the barefoot boy, like his urban counterpart, Ragged Dick-the rags-to-riches hero of Horatio Alger's popular series of novels-epitomized the belief in upward mobility that was essential to maintaining faith in democracy. Yet in an era of increasing corporate consolidation, the image of stalwart self-reliance had become increasingly out of step with the realities of the white-collar workplace. Straddling a stone wall, the barefoot boy also straddled another symbolic divide, between an agrarian and a commercial nation. Such images spoke to the middle-class preference for easily readable narratives that helped them navigate the challenges of adulthood by offering them a comforting refuge from these very demands. In much post-war genre painting, child's play anticipates and prepares the way for adult roles and responsibilities. Scenes of childhood, by Eastman Johnson (1824-1906), Winslow Homer, and others, explored the nation's own moral and social coming-of-age.

Popular Prints and the Emergence of Cultural Hierarchies

Among the many commercial firms to profit from the new rage for nostalgia and patriotic celebration were the New York City printmakers established in 1837 by Nathaniel Currier (1813-88) and James M. Ives (1824- 95), who issued a series of prints illustrating the now mythic life of George Washington: commanding the Continental Army, crossing the Delaware, and virtuously renouncing claims to power after the war. Using the most modern of means-division of labor, assembly-line production, catalogue distribution, and an early form of "niche" marketing-Currier and Ives enjoyed a market that reached beyond the United States to Europe. Ranging between 15 cents and three dollars, their prints flattered public pride in the future of the republic with images of railroads, clipper ships, steamboats, and urban monuments, as well as reassuring scenes of rural homesteads, cozy farms, and frontier adventure.

From 1840, when Currier first began providing eyewitness images of news events, until the 1890s, when other forms of mass-circulation images such as photogravure and half-tone photography replaced them, hand- and machine-colored lithographs had far greater cultural influence than works of fine art. Currier and Ives catered indiscriminately to an image-hungry public, playing to all sides. While capitalizing on the passion for patriotic images of the Union war effort, they also marketed nostalgic images of the old South after the war (fig. 9.19). Their comic images of newly emancipated blacks contained a casual racism, yet their stock also included depictions of the evils of slavery. They sold portraits of Irish nationalists and souvenirs of Irish landscape, history, and legend, along with caricatured images of Irish Americans. Neither politics, ideology, nor loyalty to their mostly native-born, middle-class buyers kept them from serving other groups, as long as a market existed.

CHROMOLITHOGRAPHY. If Currier and Ives's prints were often poorly drawn and crassly commercial, the related medium of chromolithography pursued a higher aim of inculcating "a taste for art" into a broad public. The "chroma" - a color print that often reproduced an original work of art-could be found in middle-class homes throughout the later nineteenth century. In Mark Twain's 1889 novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Hank Morgan, transported to medieval England, yearns for home-in particular, for the "chroma": "It made me homesick to look around over this proud and gaudy but heartless barrenness and remember that in our home in East Hartford, all unpretending as it was, you couldn't go into a room but you would find an insurance-chroma, or at least a three-color God-Bless-Our-Home over the door- and in the parlor we had nine." Though today we dismiss such sentimental images, for Hank they were deeply meaningful: "I saw now that without my suspecting it a passion for art had got worked into the fabric of my being, and was become a part of me. " Hank expresses the tastes of an American middle-class public for whom art was a domestic affair. Twain's own fiction was itself an often searing look at the moral evasions of middle-class culture in the United States. And yet, despite the satirical tone of the above passage, Twain was onto something.

Chromolithography did indeed encourage "a passion for art," but its commercial origins and availability to a wide public put a huge marketplace of goods within the reach of those with more money than taste. As middleclass consumers purchased mechanically reproduced highstyle goods to emulate the wealthy, those concerned with preserving class distinctions attacked the sham values and derivative products of what the cultural historian Miles Orvell has called a "culture of replication" based on Old World forms.

The condemnation was summed up in the term "chromocivilization" coined by the editor E. L. Godkin in 1874. For Godkin and others, the democratization of art threatened "mental and moral chaos." 7 But chromolithography also had many defenders among those who believed that art was not just for the privileged few but could have a refining influence on a democratic public. For Catharine Beecher, the influential co-author, with her sister Harriet Beecher Stowe, of The American Woman's Home (1869), chromolithographs provided an ideal, inexpensive, and morally uplifting wall decoration for middle-class families. Beecher was one of a growing number of newly professionalized female authors who both created and filled a need for guidance- moral and material-in the conduct of middle-class domestic life. Middle-class mothers and wives looked to authors of domestic help manuals for advice on everything from efficient use of kitchen space to the maintenance of a healthy home environment. Godkin had no reason to fear mental and moral chaos; with the help of women such as Beecher, the American middle class learned that the health of the republic depended on a virtuous and well-regulated household.

The gap between high art and popular culture widened toward the end of the nineteenth century. This contest between elitist and what would later be called "middlebrow" approaches to art persisted over the course of the twentieth century. High modernism- an art that defined itself as challenging and difficult-increasingly focused its identity around opposition to middlebrow taste, with particular reference to cultural products that demanded little from their audiences, such as the chroma.

Print Techniques

INVENTED IN 1798 in Germany and quickly refined in France and England, lithography was an autographic process; rather than having the image transferred, the artist drew directly onto the lithographic stone. Lithography thus eliminated the necessity of translating the source drawing to the surface to be printed. It was quick and far less labor-intensive than earlier relief (in which only the raised portions are printed), or intaglio (in which the image is engraved or bitten into the printing plate). As the process became rapidly commercialized by the mid-nineteenth century, lithographic firms such as Currier and Ives served a business class needing advertisements, trade cards, sheet music, and portraits, as well as meeting a growing demand for affordable art to grace middle-class homes. Taking control away from the individual artist, popular lithography divided printmaking into delineators who drew on the stone (often anonymous), inkers, printers, colorers, and "grainers" (to smooth the stone face). Requiring minimal skills, the final phase of hand-coloring prints furnished employment for women untrained in traditional crafts. This division of labor became common in such mass-produced arts of the twentieth century as animation.

Unlike the hand-colored lithographic prints of Currier and Ives, colors in chromolithography were each printed separately with a different stone; the greatest technical challenge was making sure the register, or overlap of color areas, was precisely accurate. The result, in the hands of such firms as Louis Prang (fig. 9.20), was a stunning ability to reproduce the look and texture of oil paintings: landscapes, still lifes of fruit and game, Old Master paintings, and patriotic images to instruct, refine, and please.