7.2: The Western Front

- Page ID

- 154844

The Western Front

All of Europe’s armies had been preparing for a continent-wide conflict since the unification of Germany in 1870. Most nations required some form of military service from all young men so that thousands of trained reserve soldiers could be quickly called up. All war plans relied on the quick mobilization of troops, and the extensive European railway network built in the nineteenth century moved regiments more rapidly than in any previous war (image 7.2.1). This rapid deployment meant that as soon as one side mobilized, the opposing side also had to mobilize in defense. Less time was available for calm decision-making as every nation rushed to arms. In July 1914, when Austria declared war and shelled the Serbian capital, Belgrade, Russia mobilized its military. Germany mobilized against Russia. Russia was allied with France, so France mobilized. Great Britain was allied with France, so Great Britain mobilized. The Ottomans sided with Germany as a counter to Russia. Italy, which had a defensive alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, sat out of the first months of the war until its government decided to side with France, Great Britain, and Russia in early 1915.

Because of the French-Russian alliance, the Germans knew that they would face a two-front war in any European-wide conflict. Expecting to face enemies on Germany’s eastern and western borders, the German generals had been planning for years to initially fight a defensive war with Russia in the east and an offensive war with France in the west; holding off invading Russian armies while focusing on defeating the French first.

In the first months of the war, the Germans were successful in carrying out their strategy. The German army on the Eastern Front was able to stop and even defeat the advancing Russians. On the Western Front, the German government asked permission from neutral Belgium to pass through on their way to a surprise attack on France. When the Belgians rejected the request, German troops invaded and occupied Belgium in August 1914. The Germans advanced rapidly into France but were halted by combined French and British forces, miles from Paris. Both sides dug in, creating a network of opposing trenches that ultimately extended from the North Sea to the Swiss border. Armies on both sides would be frustrated in their attempts to break through on this “Western Front” for the next four years.

Advances in military technology caused the stalemate. The nineteenth-century wars had been mobile, with generals coordinating the movements of infantry foot-soldiers, horse cavalry, and artillery cannons on the battle landscape. However, conflicts like the Crimean War and the U.S. Civil War had begun introducing better, more deadly weapons. The Charge of the Light Brigade had proven that cavalry was ineffective against dug-in artillery. And in the last decades of the nineteenth century, Europeans had perfected the use of machine guns, practicing on native populations in their colonies. By 1914 the armies of Europe had better weapons and better defenses: long-range artillery, machine guns, trenches, and barbed wire. And they were ready to use these on each other, rather than just on the so-called “barbarians” their empires ruled over.

Since neither cavalry nor infantry could stand against machine guns, attacks in trench warfare began with massive artillery barrages to “soften” the other side before troops were sent out of their trenches, “over the top” into the no man’s land between their trenches and those of the enemy, with fixed bayonets to overwhelm any enemy soldiers who had survived the shelling. When their artillery had not “softened up” the opposing forces enough, attackers would be met with enough machine gun fire to slow down any effective advance. During four long years of war, millions would either be severely wounded or killed in the “no-man’s-land” that separated the opposing armies.

Frustrated with the stalemate of trench warfare, the opposing sides on the Western Front tried new technologies and strategies in search of a decisive victory. Airplanes, first developed by the Wright Brothers in 1903, proved their value in reconnaissance and later in strafing trenches with machine guns and dropping small bombs. Early radios allowed aviators to coordinate with ground controllers. And in the spring of 1915, the Germans first experimented using poison gas on the battlefield. Within months, all sides would develop different varieties of poison gas, while racing to improve the designs of their gas masks. Poison gasses added another devastating weapon to trench warfare while achieving no significant advantage. At least 1.3 million people were killed by gas attacks. Chlorine and mustard gas were two of the most common chemical weapons used by both sides in the war. In the case of mustard gas poisoning, the effects took 24 hours to begin and it could take four to five weeks to die.

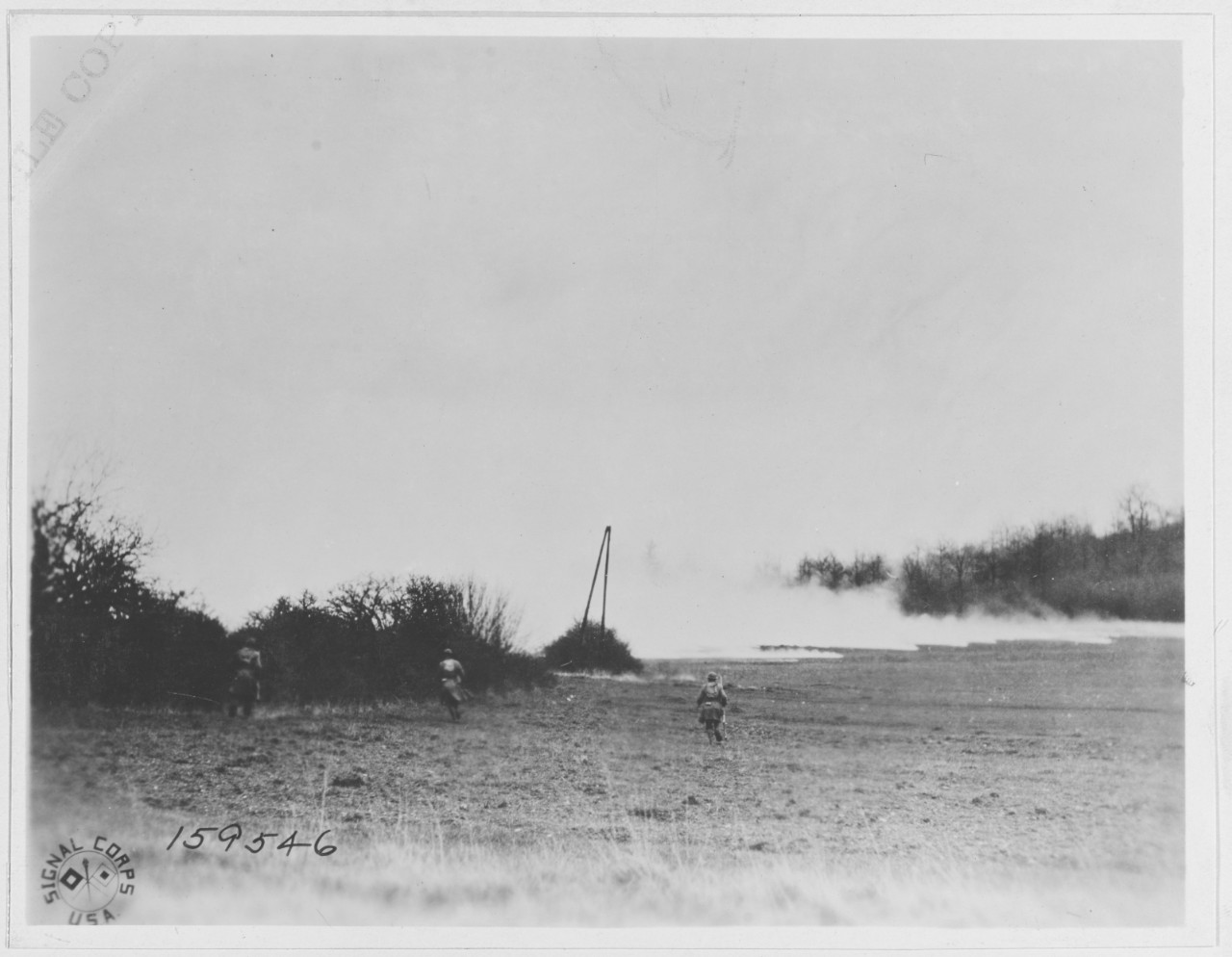

German development of poisonous chlorine gas and its first use was supervised by Fritz Haber, a scientist who won the Nobel Prize for co-inventing the Haber-Bosch process for synthesizing nitrogen from the atmosphere. After 67,000 troops were killed and wounded by the gas in its first use in April 1915, Haber’s wife, the scientist Clara Immerwahr, killed herself with his service revolver in protest. Poison gases were heavier than air, so they settled into low areas like trenches and sometimes rolled into low-lying towns, killing and injuring civilians (image 7.2.4).

Airplanes, poison gas, machine guns, and massive artillery simply became more cogs in the war’s increasingly effective killing machines. More people were killed but without any change in the outcome of the war. Enormous battles raged for months at a time at Verdun and the Somme in 1916, resulting in millions of casualties but hardly any territorial changes.

- How did advances in technology contribute to the military stalemate?

- Why do you think trenches were laid out in the way they were in the aerial view of a battlefield (image 7.2.3)?