Untitled Page 14

- Page ID

- 78684

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Chapter 5. What Are You Going to Do With That Major? An ePortfolio as Bridge from University to the World

Karen Ramsay Johnson

Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis

Susan Kahn

Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis

As liberal arts students on a campus where professional programs predominate, senior English majors at IUPUI are often uncertain of the value of their degree post-graduation. Creating a culminating reflective electronic portfolio in the Senior Capstone Seminar in English helps them develop a sense of accomplishment and take a broader perspective on their learning. Carefully scaffolded reflection within the ePortfolio prepares them for the transition to post-graduate life by prompting them to envision and articulate how they will apply their learning to new contexts as professionals and citizens in a globalizing world.

As English majors on a campus dominated by professional programs, our students are constantly asked the above question by their fellow students, their friends, and often their parents and other family members. Many are asking themselves the same thing when they begin the English Senior Capstone Seminar that we team teach. One of our main objectives for the course is to offer students a sense of the options available to them as English graduates. Equally important, we want our students to gain confidence in the value of their educational experiences as liberal arts majors, both for their future careers and for their lives beyond work.

The English Capstone at IUPUI is intended as a culminating experience for English majors that enables them to demonstrate their academic achievements and supports them as they make the transition to careers or further study. In our institutional context, these goals present particular challenges. Our mostly first-generation students enter college largely for the purpose of gaining entrée to the professional world, and the vast majority choose professional and pre-professional majors. While some of our Capstone students have made a conscious decision to major in the discipline they are most interested in, regardless of professional consequences, and others plan to pursue a graduate or post-baccalaureate professional degree, most begin the course with some anxiety about the utility of their degree in English. We have even had students tell us that their parents actively disapprove of their choice of major. On a predominantly professional, first-generation campus, we thus face the special challenge of helping humanities majors construct a bridge between their academic studies and their life beyond the academy. To meet this challenge, we use IUPUI’s electronic portfolio as a site for students to present and reflect on their educational accomplishments.

Contexts

The University: An Urban Research Institution

Our institution, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI), is an urban research university, with over 30,000 students and some 21 schools. Professional education, particularly in the health and life sciences, is a strong component of the university’s mission; the campus is home to the state’s only medical school and the nation’s largest nursing school. Approximately one third of our students are in graduate/professional programs. Professional schools dominate at the undergraduate level as well. Among the 15,300 undergraduate students who had declared a major in 2009, only about 3,550 chose to pursue studies in traditional liberal arts and sciences disciplines. Indiana has typically had low educational attainment in comparison to other states and IUPUI students’ family backgrounds reflect this trend: in 2008, only 19 % of undergraduates reported that both parents had completed college; 55 % came from families where neither parent had a bachelor’s degree. Almost all students commute to campus.

While student demographics have changed over the years, with more undergraduate students entering directly from high school, the average age of students in the School of Liberal Arts is 26. About 40% are 25 or over, while 33% are part-time students. English majors offer a slightly more traditional profile, with 44% over the age of 25 and 31 % part-time students. A majority of seniors began their higher education at another campus and some have transferred more than once. Many undergraduates already have families of their own and most work while attending college. With all of these commitments, our students—in contrast to traditional undergraduates—often do not view higher education as the main focus of their lives. And because so many are transfers who have taken time off from college and/or changed majors at least once, they may perceive their undergraduate education as a set of fragmented, unrelated experiences. Another challenge for us in the Capstone is thus to help students “connect the dots” among their courses and out-of-class learning experiences, so that they can see their education as a meaningful and coherent whole.

The Department of English: A Multifaceted Department

The English Department’s Capstone seminar began about ten years ago, when the department experimented with replacing its tracks with a single English Studies major in which students were required to take a common introductory course, the Capstone seminar, a range of courses across the tracks, and a set of electives. Four years ago, in response to a recognition that many students still wanted to specialize in a track, we reinstated the tracks, while incorporating an individualized program as a sixth track The department’s nearly 300 majors are now divided primarily into five tracks: Literature, Linguistics, Writing and Literacy, Film Studies, and Creative Writing. Each track then established its own introductory course, but we have retained the common Capstone. Students in each track are still required to take two to four major-level courses in other tracks, so the Capstone has the secondary purpose of reaffirming the interconnection of the tracks. Currently, Literature and Creative Writing offer students the option of taking a senior seminar rather than the Capstone Seminar, but most students continue to choose the Capstone.

The Capstone Course Design

For the sections of the English Capstone that we team teach, we want students to achieve these outcomes:

- Integrating learning across courses and disciplines (and for many students, across work and academic experiences) and making sense of disparate experiences, so that their education adds up to more than just a set of disconnected courses or requirements completed.

- Articulating what they have learned and gained from their studies in English and the liberal arts in terms meaningful to potential employers and other audiences.

- Using evidence to substantiate claims about the skills and abilities they have developed; for example, simply announcing that one is an effective writer and researcher, without pointing to evidence and providing some analysis of that evidence, is inadequate.

- Gaining insight into their own learning processes, so that they feel empowered to take control over their learning outside formal educational settings.

- Developing confidence in the value of a liberal arts/English degree. As we have noted, for our professionally oriented student population, this can be challenging.

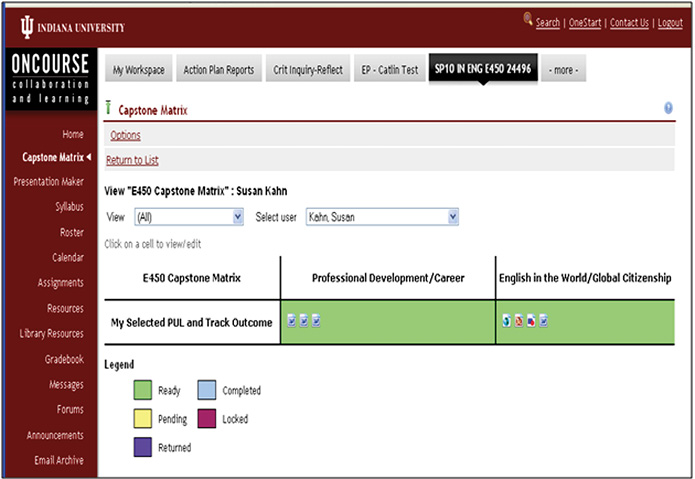

With these outcomes in mind, we have designed the current iteration of the course around two main components, which we call “Professional Development and Career Planning” and “English in the World and Global Citizenship.” These components are intended to focus students’ reflections on the future, while encouraging them to consider how they have developed over the course of a liberal education as potential professionals and as active citizens at both local and global levels. The structure of the ePortfolio learning matrix that students develop mirrors these two components, with one major section devoted to career and a second section to “English in the World” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: English Capstone Matrix.

Both of the main components of the course are scaffolded by assigned readings, guest speakers, and online and in-class discussions. Some readings and speakers directly address the value of a liberal arts education to the world of work today. For example, a 2006 New York Times op-ed article by Thomas Friedman, “Learning to Keep Learning,” argues that the 21st-century workplace demands professionals who can learn continually, think creatively, work with ideas and abstractions, and integrate concepts across disciplines—the kinds of abilities fostered by study in the liberal arts (2006, December 13). Guest speakers include not only School of Liberal Arts career placement staff, but graduates from the Department of English, often recent students in the course, who discuss their job search strategies and the ways in which their studies in the liberal arts generally and English specifically proved relevant to a diverse array of work experiences. Similarly, for the “English in the World and Global Citizenship” theme, students read an essay by philosopher Martha Nussbaum that speaks to the importance of imagination and empathy—capacities closely linked to one another, in Nussbaum’s argument—for effective citizenship and action in the world (Nussbaum, 2005). Speakers on this theme include senior faculty members and administrators from liberal arts fields who are involved with issues of civic engagement and international affairs.

The Professional Development and Career Planning Component

For this component of the course and the ePortfolio matrix, students are asked to collect several pieces of past work, or “artifacts,” that exemplify key career skills they have developed in the course of their education and work experience and that are related to one of IUPUI’s general education outcomes (called the Principles of Undergraduate Learning or PULs) and an outcome for their chosen track in the English major. These examples might represent a student’s best work or might demonstrate the evolution of an ability or skill over a period of time. Students also create a résumé and cover letter, in consultation with career professionals in the School of Liberal Arts. Finally, they develop a career reflection that includes analysis and evaluation of their portfolio artifacts in relation to their selected PUL and track outcome, as well as discussion of areas they need to strengthen or continue developing. Students who have identified a specific career interest write the reflection with an eye to the abilities and skills needed for success in that career. For the many students who have not decided on a career path, the artifacts, résumé, and reflection can address the development of abilities and skills key to effectiveness in any professional field. We have found that the scaffolding provided by the readings, speakers, online forums, and discussions helps students to develop a vocabulary for discussing their learning in terms that are relevant to potential employers. Additional scaffolding is supplied by a series of reflection prompts. (See Appendix, Activity 1 for a list of the prompts we used for the Career and Professional Development reflection in Spring 2010.)

The English in the World and Global Citizenship Component

The main assignments for the English in the World and Global Citizenship component are the Senior Project and the English in the World reflection essay. The Senior Project includes a project plan, a complete early draft of the project, an annotated bibliography, and the final project, which the students present to the whole class at the end of the semester. Because our students come from all of the tracks in the major, they have their choice of project topics, but each project must contain a research component. Students can also opt to do a group senior project, though most choose the individual option. For the reflective essay in the ePortfolio, students are then asked to draw on the project, as well as other portfolio artifacts, to consider how their studies in English and in their particular tracks have shaped their identities in “the world”—e.g., as members of a particular community or culture, as global citizens, or as lifelong learners able to contribute to society in particular ways. (See Light, Chen, and Ittelson, 2012, and Steinberg and Norris, 2011, for more extended discussion of how ePortfolios can help to advance development of a “civic” identity. A list of the prompts we used for this section of the portfolio in Spring 2010 can be found in the Appendix, Activity 2.)

The Capstone Portfolio

This year, we began using a two-part portfolio process that culminates in a webfolio. The process is based on the portfolio tools available in our university’s learning management system, Sakai, known as Oncourse at Indiana University. Beginning in 2005, Kahn and Sharon Hamilton designed and refined a matrix system, in which students practice a kind of integrative thinking that Kahn and Hamilton have called “matrix thinking” (Hamilton & Kahn, 2009). In the current iteration, we use a simple two-cell matrix (see Figure 1), which both continues the dual focus that is characteristic of matrix thinking and serves as a training ground to prepare students for what Helen Chen terms “folio thinking” (Chen, 2009). Using the Principles of Undergraduate Learning and at least one goal from those emphasized by their tracks within the English major, students collect artifacts, save and revise reflective commentary, and create a storehouse for their potential webfolio materials.

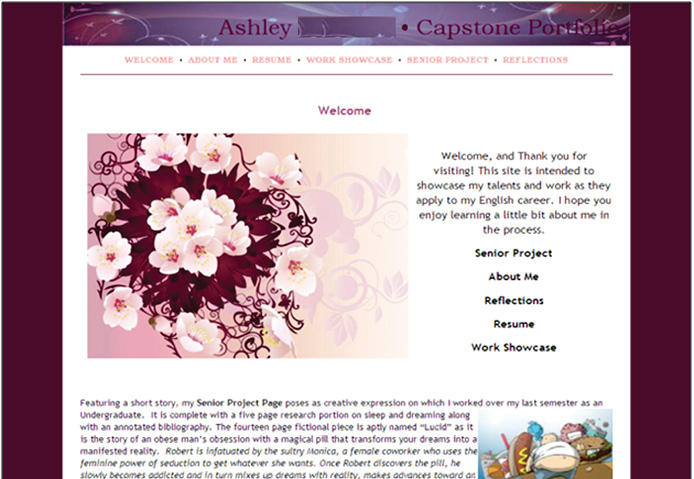

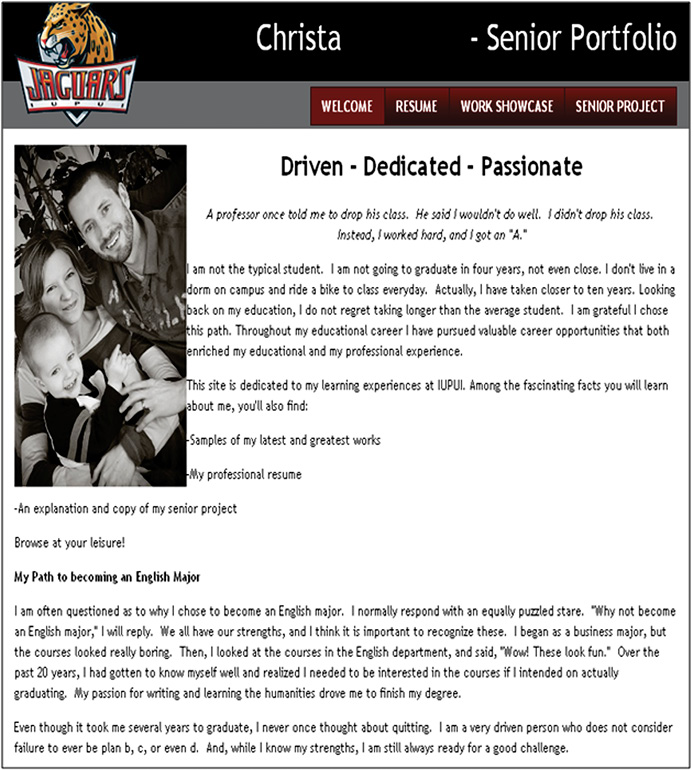

For the webfolio, students can opt to use a platform within Oncourse or other web development software of their choice. Each student is required to include four specific sets of materials: an introductory welcome page, an up-to-date résumé, the senior capstone project, and their two reflective essays. They may organize these materials in any configuration that they prefer. They can also add extra pages to highlight specific skills, interests, or causes and organizations that they support. Some students choose to add their course portfolios to other websites that they maintain or to which they belong. (The appendix includes screen shots from webfolios created with Oncourse Presentation Maker.)

Student Learning in the Capstone Portfolio Experience

Preparing Students to Reflect

Simply asking students to “reflect” on a piece of work or on an experience is unlikely to yield results that are meaningful to them or to the faculty members who read those reflections. We want students’ reflections to contribute to their accomplishments of the outcomes for the course and we gear our preparations for reflection to those outcomes.

We begin preparing students to reflect by discussing what we mean by “reflection” and what we hope they will achieve as a result of reflecting. A particularly helpful tool has been a document titled “Development in Reflective Thinking” (see Appendix, Table 1), originally created as a descriptive rubric at Alverno College and later adapted by Sharon Hamilton for IUPUI (Hamilton & Kahn, 2009, p. 96). The document, which we distribute to and discuss with our students, describes characteristics of “introductory,” “intermediate,” and “advanced” reflective writing. For example, in “introductory”-level reflections, students tend to narrate “what I did” to create a piece of work, to make general claims of competence or mastery without evidence, to repeat evaluators’ judgments, and to state assumptions without explaining or questioning them. “Advanced”-level reflections, by contrast, exhibit characteristics associated with higher-order thinking skills: analysis of thought processes (i.e., metacognition); use of evidence to support arguments; questioning of assumptions and awareness that assumptions are shaped by culture and individual experience; ability to self-assess; high-level conceptual thinking; and synthesis of ideas from multiple disciplinary and experiential frameworks.

Keeping in mind that most reflections do not fall neatly into one developmental category, here are two brief reflection excerpts that serve, respectively, to illustrate some of the characteristics of “introductory” and “advanced” reflection:

Example 1: Second in this section is my outline for a graphic novel titled What Good Men Dream. This was my first attempt at writing anything like this. Over the course of the semester every student worked on an outline for a story and at the end we polished it and presented the full outline with a few sample pages. Mine went very well and the teacher was pleased with it.

Example 2: “Afternoon at Grandma’s House” was my first attempt at writing a form poem. I chose the sestina because of its difficulty, and I was very pleased with the way that my piece came out. I found that I had a little difficulty keeping the line lengths consistent as the piece went along, but I focused on keeping my language compact and precise. Wordiness is something I struggle with, so this was a real challenge to me.

After discussing the “Development in Reflective Thinking” document with the class, we spend part of a class session working in small groups to evaluate several reflections written in past sections of the class. While the students’ conclusions do not always agree with our own, this exercise provides the opportunity for students to see several examples of reflections written at varying levels of intellectual maturity and sophistication and to discuss and defend their judgments about the effectiveness of each. To avoid giving the students the impression that there is one “right” way to approach reflection or that we are looking for writing that adheres to a specific formula, we try to provide more than one example of “advanced” reflection.

Now students write a rough draft of their career reflection, using one or more of the questions or prompts we provide. Thoughtful prompts are essential to supporting students’ reflective writing (Zubizarreta, 2009, pp. 11-13). Our prompts are derived in part from the course outcomes and in part from the observations in the “Development in Reflective Thinking” document. In the next class, we break up into groups of two or three to critique one another’s drafts, using a review form that we created based on “Development in Reflective Thinking.” Each student receives at least one and, ideally, two written and oral critiques of the first draft. At this point, we ask students to write the “final” version of their career reflections.

Outcomes of ePortfolio Development

Do students achieve the outcomes we seek for the ePortfolio and the class as a whole? It depends. Kahn notes that in earlier iterations of the class, where students were asked to develop a much more extensive ePortfolio in lieu of the traditional senior project, they were given more practice in writing reflections and the reflections showed greater sophistication. At the same time, too much reflective writing can make reflection seem routine, a rote exercise. We have yet to find the ideal balance between more traditional class work and portfolio development—and perhaps this balance is different for each class and even each student.

Many students, however, do find the combination of readings, speakers, consultation with a career placement professional, and development of the ePortfolio helpful in enabling them to articulate more clearly to themselves and others the value of their English degree, both to the workplace and to life beyond the workplace. In particular, reviewing a body of past work created over time and then reflecting on it can be powerful; students who have kept examples of early work done in college often note that they had not realized the extent of their intellectual growth since they were freshmen. One student writes:

I no longer see what I have to offer as an English job hunter in mere terms of degree possessed and years of experience ... I look at what I have to offer in a larger context. Beyond the essentials in my résumé that I share with all other graduates, I now see capacities in critical thinking, communications, and multi-project analyses. All these capacities can be supported with the creative and scholarly material in my matrix.

Some students show visible growth in their capacity to reflect on their own learning and experiences over the course of the semester. A student whose first reflection in the semester was broadly focused, with only a few references to professors and courses and brief statements of what she learned in each, had, by semester’s end, developed the ability to connect her years of work (often with troubled youth) to her own background of growing “up poor even by poor people’s standards,” and her English major to her future:

Beyond my own hunger for the kind of learning that I can only get from sitting among a group of other learners and hashing issues out, I want to share it. I want to bring that opportunity to people in shelters who are just too bone-tired to do more than sit in a circle and talk about life and the shit it throws at you .... I feel like it’s my role in life to be some sort of liaison between those who want, and the knowledge they want to obtain but don’t quite know how to get it.

Another student, who had served in the military in Iraq and returned to school to complete a double major in English and Political Science, makes powerful connections among several liberal arts disciplines as she writes about the development of her critical thinking skills:

IslamY107.doc exemplifies my ability to be a critical thinker because I had to put forth significant effort to separate my emotion from the facts and research. This skill was one of the first skills taught to me in college. I believe that objectivity and rationality are at the core of every serious student—this paper shows me that I can be a serious student. Every class that I have taken in political science, English, and philosophy has emphasized the importance of looking past the surface of things. Additionally, my education in the liberal arts has taught me that there is much more to things than what my emotions tell me there are. There is an entire world of people out there, each person possessing a uniqueness of mind and emotional experience. There are several cultures and societies that need to be taken into consideration before my own. My emotions are only central to my own experiences, and my critical thinking skills allow me to leap outside of my own experiences.

Cathy, a middle-aged, middle-class wife and mother, came to IUPUI when her children reached high school age; as she writes, when she graduated from high school, she “did not have the parental support to be anything other than a wife.” She credits her Capstone project with clarifying her life’s purpose: “After contemplating my final project, I have discovered that the works I researched are a direct reflection of who I am and my place within society.” Now, she says, she wants “to help others achieve a college education and experience for themselves [a] transformation [like the one that she experienced].”

As these four students illustrate, the diversity of our student body, especially in terms of age, class, and life circumstances, guarantees that their experiences of reflection and of its outcomes will also be different. Another common category of student at our university is the one who begins at a traditional liberal arts college or university and becomes disillusioned. Ted, who is from a well-educated family on the west coast, dropped out of a liberal arts college to work for Americorps and for several non-profit ventures. Perhaps the most sophisticated thinker in our sections of the Capstone, he began the class with the sense that his education would give him nothing more than a necessary credential. Yet even he acknowledges in his final reflection that his training has come to shape his thinking. After a semester of reading, reflecting, and interacting with guest speakers and students, Ted had arrived at a somewhat better place; talking with guest speakers and fellow students about work that might advance his ideals, he became more active in class discussion and in on-line forums and e-mail exchanges. His second reflection supplements the theme of work learning and focuses on a series of obviously successful course experiences; for example, he integrates his English training with his work in a computer science course:

Even when I tried to study other disciplines I found myself still thinking within the Liberal Arts mindset. The clearest example of this was a paper I wrote about Charles Babbage during my Fundamental Computer Science Concepts course. While looking at the history of computing, as it is commonly taught, I noticed some interesting narrative gaps and accepted assumptions. My paper focused only on assumptions made by present historians looking back at Babbage, but the impulse for the paper was some fundamental errors I noticed in the way the history of computing is told. As I mentioned, there are many assumptions made about what Charles Babbage intended to produce (given that he produced very little), but even worse the entire narrative stems from an idea of technological determinism—that is technology advanced the way it did and when it did because it was bound to. While a common way of viewing any topic within history (e.g., WWII was inevitable because of WWI) it is only one view, and completely ignores the idea of contingency—that is just because something has occurred does not mean that it was certain to occur.

Issues Emerging Through Assessment

While we are gratified when students make visible progress in their thinking and integrative skills or arrive at important insights over the course of their Capstone experience, some issues have been difficult for us to resolve:

- It is difficult to devise instructions and prompts that work for a wide range of students. While the diversity of our student body is, in most respects, one of IUPUI’s greatest strengths, it can be hard to address all levels of preparedness at the same time. For example, while weak students cannot begin to reflect without very precise instructions and insecure students need the reassurance that such instructions provide, strong students tend to find them limiting. In one section particularly, while discussing the reflection prompts and examples, the stronger students pointed out that it is easy to see what is “right” to say. They viewed the “good” sample reflection as one in which the writer was saying what he or she knew the instructor wanted to hear, parroting the language of the PULs and the rubric, and engaging in what they saw as a relatively mindless exercise of finding examples. Although the bad example was visibly poorly written and lacking in any serious thought, even the strongest students viewed this writer as “honest,” because he or she was not trying to please the instructor. To a great extent, this resistance diminished as the semester progressed, but we would prefer to have a range of prompts that can be geared to individual needs.

- Because many of our students have significant work experience (often full-time work), they can experience a bifurcation of identity, in which their student selves seem distanced from their identities in the work place. Thus, unlike traditional students, they need to see a direct connection not only between their work and their courses, but also between academic and professional reflection. A vivid example of this need appears in the reflections of our recent student, Jay. Jay dropped out of his first college to take a full-time job with a web-based company; he has had enormous success in his job, including being selected as the company’s “first ever employee of the month, standing out beyond others as a hard-working, ambitious employee always ready to take on new challenges.” Thus, he has become convinced that “most of my skills for the ‘real-world’ have been honed in the real world.” For Jay, integration of his academic and workplace learning was not a meaningful goal, and Jay is not alone. Some of our students continue to view education purely as a credential, either because, like him, they have been successful without it or because they have “learned,” either from poor teachers or from parents, that the main goal is to have the diploma. Thus, they tend to undervalue reflection in an academic setting, because they view it specifically as an academic process.

- On the other hand, for other students, inflated ideas about the value of a baccalaureate degree can inhibit the reflection process. As we have noted, a large percentage of our students are first-generation college students, and they often have an unrealistic view of what a college education means. They rightly view college graduation as a major accomplishment, but, because they have known very few college graduates as they grew up, they may believe that the degree credential itself will enable them to move directly into the job of their choice. They also, however, continue to underrate their own accomplishments. They need to recognize that, valuable though their college experience is, their earlier experience must also figure into their examined life, as Plato called it; they must learn to see how their pasts inform their presents and their futures.

Addressing the Issues

The most immediate issues that we need to address stem from some students’ lack of familiarity with the process of writing reflective essays; we have noticed over time that almost all of the second essays are far better than the first ones. Accordingly, we have reformatted the reflection process to allow for more specific reflections and more individual input. Our next iteration of the course will follow this process:

- Have students do a reflection early in the semester, to be revised and expanded near the end of the semester.

- On the first or second day (or first day after drop/add), have students explain what they think reflection means and how they think that one should go about writing a reflective essay on one’s education as an English major.

- First artifact: Write a short (2-3) page reflection specifically on that piece, using PUL and track goal.

- Second artifact: Write a short (2-3) page reflection specifically on that piece, using PUL and track goal.

- First Reflection: Write a 4-5 page reflective essay referring to those artifacts and reflections.

- Students will then make a list of the main points in that essay in a word processing program or in a blog; as the semester progresses, they will keep notes (checked periodically) on what new ideas they have about those points or on others that they add to the list: a reflective journal. For students who have trouble doing this, we will offer specific journal topics related to readings, guest speakers, and the individual student’s track and career goals.

- Students will create a skills résumé (can be in addition to a standard résumé).

- Students will write a short reflective essay for the Senior Project.

- Second Reflection (revision of Reflection 1): As the last assignment, students will revise the first reflective essay, adding new ideas from the journal and referring to the skills résumé, senior project, and project reflection for more ideas (7-10 pages).

We also want to address the issues specific to students who have difficulty integrating the academic and work aspects of their lives, but we believe that all of our students will benefit from understanding that electronic portfolios, with their central component of reflection, are increasingly important not only to higher education, but also to employers. Thus, we are in the process of identifying two or three companies in Indianapolis that use electronic portfolios and requesting information on the purposes for which they are used, the guidelines that are given to employees preparing them, and samples of exemplary portfolios. If possible, we will also have a company representative who is involved in the process visit our class.

Conclusions

As the above discussion suggests, our versions of the English Capstone Seminar and the Capstone portfolio remain works-in-progress, particularly when it comes to helping students reflect in more meaningful ways. In the most recent iteration of the course and portfolio, however, our meshing of the matrix format developed by Kahn and Hamilton with the webfolio proved largely successful, in our opinion. The matrix continues to be enormously helpful to the students because of the scaffolding it enables us to provide, but they are, not surprisingly, more engaged and stimulated by the experience of creating Web pages. This holds true even for students who are not normally frequent technology users. An added benefit is that they are easily able to envision a potential employer visiting their webfolios; many students say that they expect to maintain and update their webfolios regularly. While the materials included in the webfolio are still informed by matrix thinking, the webfolio adds new levels of integration and provides students, professors, and other site visitors with a highly individualized, immediately engaging, and visually exciting representation of student work and reflection.

We are immensely grateful to our students who, over the years, have shared their time, work and thoughts with us; we especially thank those who have allowed us to share their work with our readers. The English Capstone has been at least as powerful a reflection experience for us as it has for them. Indeed, our experience of reflection has reaffirmed for us the vanity of “conclusions.” Even in the process of writing this essay, we found ourselves entertaining new ideas about how we might refine the course, and we welcome any comments or suggestions that our readers may offer.

References

Barrett, H. (2004). Electronic portfolios as digital stories of deep learning: Emerging digital tools to support reflection in learner-centered portfolios. Retrieved from http://electronicportfolios.org/digistory/epstory.html

Batson, T. (2010). ePortfolios, Finally! Campus Technology. Retrieved from http://campustechnology.com/Articles/2010/04/07/ePortfolios-Finally.aspx?Page=1

Cambridge, D., Cambridge, B., & Yancey, K. (Eds.). (2009). Electronic portfolios 2.0: Emergent research on implementation and impact. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Chen, H. L. (2009). Using eportfolios to support lifelong and lifewide learning. In D. Cambridge, B. Cambridge, & K. B. Yancey (Eds.), Electronic portfolios 2.0: Emergent research on implementation and impact (pp. 29-35). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Cohn, E. R., & Hibbitts, B. J. (2004). Beyond the electronic portfolio: A lifetime personal web space. Educause Quarterly, 27(4). Retrieved from

http://www.educause.edu/EDUCAUSE+Quarterly/EDUCAUSEQuarterlyMagazineVolum/BeyondtheElectronicPortfolioAL/157310

Friedman, T. (2006, December 13). Learning to keep learning. Retrieved from http://select.nytimes.com/2006/12/13/opinion/13friedman.html?_r=2

Heinrich, E., Bhattacharya, M., & Rayudu, R. (2007). Preparation for lifelong learning using ePortfolios. European Journal of Engineering Education, 32(6), 653-663.

Jones, S., & Lea, M. R. (2008). Digital literacies in the lives of undergraduate students: Exploring personal and curricular spheres of practice. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 6(3), 207-216.

Kahn, S., & Hamilton, S. J. (2009). Demonstrating intellectual growth and development: The IUPUI ePort. In D. Cambridge, B. Cambridge, & K. B. Yancey (Eds.), Electronic portfolios 2.0: Emergent research on implementation and impact (pp. 91-96). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Light, T. P., Chen, H. L., & Ittelson, J. (2012). Documenting learning with eportfolios: A guide for college instructors. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nussbaum, M. (2004). Liberal education & global community. Liberal Education 90(1). Retrieved from http://www.aacu.org/liberaleducation/le-wi04/le-wi04feature4.cfm

Siemens, G. (2004). ePortfolios. Elearnspace: Everthing elearning. Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/eportfolios.htm

Steinberg, K.S., & Norris, K.E. (2011). Assessing civic mindedness. Diversity & Democracy: Civic Learning for Shared Futures, 14(3), 12-14

Yancey, K. B. (2009). Reflection and electronic portfolios: Inventing the self and reinventing the university. In D. Cambridge, B. Cambridge, & K. B. Yancey (Eds.), Electronic portfolios 2.0: Emergent research on implementation and impact (pp. 5-16). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Zubizaretta, J. (2009). The learning portfolio: Reflective practice for improving student learning (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Appendix A

Activity 1: Prompts for Career and Professional Development Reflection

As you write your reflection, please focus your thinking on one of IUPUI’s Principles of Undergraduate Learning and one of the outcomes for your track within the English major. You might consider some (but probably not all) of the following questions:

- How is your classroom learning of your selected PUL and English outcome related to work and career issues? How have these learning experiences contributed to your development as a professional?

- How do your chosen artifacts demonstrate your ability to apply your selected PUL and English outcome to your professional work? (Or how did creating these artifacts contribute to your professional development?) Do they show a trajectory of professional development? If so, how?

- If you have selected a career, how does your choice of major specifically relate to the requirements of this profession?

- In what ways do you need to improve to prepare further for your career?

- Be sure to provide a well-supported critical analysis of your selected artifacts in the context of PUL and English outcome and to use the artifacts to exemplify your insights.

- Also be sure to specify which PUL and track outcomes you’re addressing and to use the examples as evidence for your claims.

You might find it helpful to think of your reflection as either an extended argument (with your work samples as evidence) or as a narrative about your learning over time (again citing your work examples or specific aspects of them as evidence).

Activity 2: Prompts for English in the World and Global Citizenship Reflection

Your “English in the World” matrix cell should demonstrate the ways in which your studies in English and in your particular track have shaped your identity in “the world”—e.g., as a member of a particular community or culture, as a global citizen, as a lifelong learner able to contribute to society in particular ways, or in relation to some other aspect of the world beyond your college education. If they’re relevant, please also consider courses in other disciplines and work or intern experiences. Think of our capstone seminar as a bridge between your education and your life in “the world.” As you select examples of past work to upload, consider how the skills and values you’ve acquired from your studies in English and other disciplines will influence and support you as an individual, family and community member, and citizen of and in the world. Questions to think about when you write your reflection (remember you shouldn’t try to respond to all of these—pick one or several and organize your reflection around those):

- In what ways do your artifacts/work examples and senior capstone project demonstrate your ability to identify and question assumptions (your own and others)?

- In what ways do your artifacts and senior capstone project demonstrate awareness of who you are as a citizen of a local culture and global society?

- What else do your artifacts and senior capstone project demonstrate about your strongest skills as you move from your education (or this stage of it) to the rest of your life?

- Can you identify specific aspects of your major that have shaped your self-concept and aspirations? For example, has your major (or track) influenced how you see yourself as a local and global citizen? In what ways are these influences reflected in your artifacts and senior capstone project? (If you’re a double major, you may consider both majors.)

- Do your artifacts, culminating in your senior capstone project, show a trajectory of development as a learner in relation to your PUL and track outcome? As a citizen? If so, how?

- How is your choice of major related to the abilities necessary for lifelong learning? How do you need to improve those abilities? Cite evidence from your artifacts and senior capstone project.

Be sure to provide a well-supported critical analysis of your selected artifacts, including your senior capstone project, in the context of PUL and English outcomes and to use the artifacts to exemplify your insights.

Table 1: Development in Reflective Thinking

|

Areas of Development |

Introductory |

Intermediate |

Advanced |

|

Ability to self-assess

|

|

|

|

|

Awareness of how one learns

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Derived from a model of “Developmental Perspectives on Reflective Learning”

Alverno College 2004. Sharon J. Hamilton 2005. Reprinted with permission.

Appendix B. Webfolio Screen Shots

Figure 2. Webfolio Screen Shot 1.

Figure 3. Webfolio Screen Shot 2.