Ch. 15 AUDIENCE

- Page ID

- 53501

While an effective sense of purpose is critical, an understanding of your audience is just as important. Whether your goal is to impart information or to persuade someone to think differently about life, how can you expect success if you don’t know to whom you are speaking? [Image: Stephan Wieser | Unsplash]

DEFINITION TO REMEMBER:

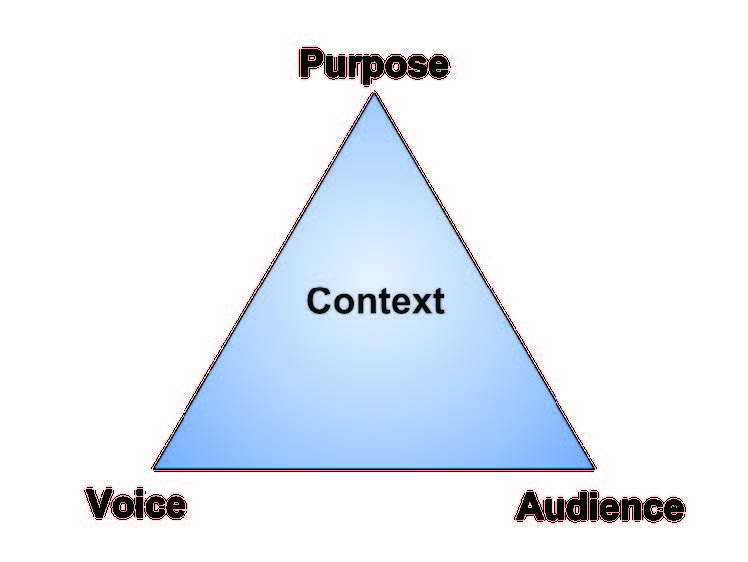

A 21st Century Rhetorical Triangle

“As important as it is to have writing that is technically correct, your audience is more important. Codifying the importance of who and how has helped me in developing relationships.” Byron Deming, Quality Assurance Analyst

RULES TO REMEMBER:

1. The Rhetorical Triangle is three-cornered to demonstrate that each of the three components is of equal importance. Most of us are taught that we should have a purpose when we write, but few of us are taught the importance of audience. When we are young, our audience is our teacher, which is likely why we are not taught to ponder a different, larger, or more complex audience. But take heed: While an effective sense of purpose is critical, an understanding of your audience is just as important. Whether your goal is to impart information or to persuade someone to think differently about life, how can you expect success if you don’t know to whom you are speaking?

2. The first step is to identify your audience. As you ponder, consider the following:

◦ Who, aside from you, has a stake in finding answers about this topic?

◦ What do they have to lose or to gain from the issue?

◦ Who has already written about or spoken about this issue?

◦ Who would want to learn more about this issue? Why?

◦ Who would disagree with you on this issue? Why? Write a single sentence in which you describe the audience you are considering.

3. The next step is to define your audience. The more specific your answers are and the narrower your audience is, the better you can tailor your writing to address your audience specifically and effectively. Consider the following questions:

◦ What is the primary age group of your audience?

◦ What is the primary gender?

◦ What is your audience’s race and/or cultural background?

◦ Where is your audience located?

◦ What is their education level and economic status?

◦ What primary religious beliefs do they hold?

◦ What does your audience value? What are their interests?

◦ Are you addressing a specific group of people? For example, are you addressing coworkers, business executives, teachers, or liberals?

4. How much does your audience know about your topic?

◦ How much background will you need to provide?

◦ Are there specific terms or jargon that you will need to define, or will your audience have a familiarity with that language already?

◦ What bias does your audience hold about your topic? What assumptions might they make, and how can you address those assumptions directly?

◦ What other misconceptions might your audience have about the topic?

5. Keep in mind what will move your audience. Will the members respond best to emotion, logic, credible or famous sources, or a combination of the three?

6. Picture your audience as you prewrite, as you write, and as you revise. If you are writing to a single person, picture that person sitting across from you, listening as you read your ideas aloud. If you are writing to a convention center full of people, picture their sea of faces as they hear your words. At what point are they interested, angry, bored, curious, or emotional? What can you do to ensure that your approach is the most effective approach possible for the audience you plan to address?

7. How do you hope your audience will think differently about the world after reading your work? Has your tone achieved your purpose? Have you included sources that will interest and persuade your audience?

COMMON ERRORS:

• Assuming that the instructor is the audience, and neglecting to realize the importance of weighing who your audience is every time you write.

• Arguing for a “general audience.” There is no such thing as a general audience. An audience can be exceptionally narrow or exceptionally broad, but there are always distinguishing factors. Take the time to answer the questions in item #2 above every time you write, and you may be surprised.

• Neglecting to narrow your audience appropriately. The narrower your audience is, the more effective and persuasive your writing will be. It is far easier to write to a group of 16 year olds than to a general age group spanning from 3 to 103. Some of the key factors to consider as you narrow, include: age, location, education, class, and career choice.

• Forgetting to focus on the audience with every word, every fact, every claim, every source, and every story. Too often we slide into a nonexistent or general audience; it takes work to keep ourselves focused on the audience we intend to reach.

EXERCISES:

| Exercise 15.1 |

|

Consider five writing tasks that you have completed recently, whether for school, work, or home. What was the purpose of each? Who was your audience for each? Did you write with the audience keenly in mind? How might an intentional sense of audience have changed your approach to each of those writing tasks? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. |

| Exercise 15.2 |

|

Select a writing task that you have completed recently or that you intend to complete, and answer the following questions: 1. Who, aside from you, has a stake in finding answers about this topic? 2. What do they have to lose or to gain from the issue? 3. Who has already written about or spoken about this issue? 4. Who would want to learn more about this issue? Why? 5. Who would disagree with you on this issue? Why? Write a brief paragraph in which you describe the audience you are considering. |

| Exercise 15.3 |

| This level of audience analysis should happen every time you write, whether you are writing a text, an email, a work document, or an academic essay. Consider a writing assignment that you will need to complete in the next week. What is the assignment, and what will your purpose be in writing this assignment for your audience? Write an Audience Description in which you describe your audience carefully and thoroughly. An effective Audience Description should be a brief but thoughtful paragraph that describes (1) who your audience is, using the questions in items #2 and #3 above for guidance; (2) what approach you will use with that audience; and (3) how you will reach that audience (blog? email? pamphlet? website? publication? magazine? etc.). |