1.2: Native American

- Page ID

- 68421

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The selections of this section come from six tribes whose home-lands cover the majority of the United States’ eastern seaboard as well as regions in the midwest and southwest. The Micmac or Mi’kmaq tribe belonged to the Wabanaki Confederacy and occupied a region in southeastern Canada’s maritime provinces as well as parts of New

oldest political entities in the

Confederacy were called the Iroquois by the French and the Five Nations by the English. The latter refers to the five tribes that made up the confederacy: the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca tribes. The name was changed to Six Nations when the Tuscarora tribe joined in the eighteenth century. Their territory covered the majority of New York with some inroads in southern Canada and northern Pennsylvania. Called the Delaware by Europeans, the Lenape tribe’s territory included what became New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania, southeastern New York, northern Delaware, and a bit of southern Connecticut. The Cherokee tribe occupied the southeastern United States as far north as Kentucky and Virginia and as far south as Georgia and Alabama. The Winnebago, or the Ho-chunks, lived in Wisconsin. Finally, the Zuni or the A:shimi were descendants of the ancient Anasazi and Mogollon cultures of the southwestern United States and occupied the area called New Mexico.

Missionaries and ethnologists were some of the first collectors of Native American tales. The missionaries often learned Native American languages and customs as a way to better proselytize the tribes, and some became at least as interested in these studies as in their religious missions. Moravian missionary John Heckewelder recorded the Lenape account of first contact before the American Revolution and published it early in the next century as part of the transactions of the American Philosophical Society, an outgrowth of the Federal era’s zeal for knowledge and scientific study. Baptist missionary Silas Rand ministered to the Micmac tribe and recorded the first contact story told to him by Micmac man Josiah Jeremy. A self-taught linguist, Rand also published a Micmac dictionary. Toward the latter half of the nineteenth century, the developing field of ethnology—the analytic study of a culture’s customs, religious practices, and social structures—fueled the study of Native American culture. The Cherokee accounts recorded by James Mooney and the Zuni accounts recorded by Ruth Bunzel were first published as part of the annual reports produced by the Bureau of American Ethnology, a federal office in existence from 1879 to 1965 that authorized ethnological studies of tribes throughout America.

Image 1.1 | Flag of the Wabanaki Confederacy York and New Jersey. One of the Artist | User “GrahamSlam” License | CC BY-SA 4.0 Source | Wikimedia Commons new world, the Haudenosaunee

Paul Radin—like Bunzel, a student of cultural anthropology pioneer Franz Boas—did his fieldwork for his doctorate among the Winnebago and there recorded the tribe’s trickster tales. While many of the accounts come from outsiders embedded for a time within tribes, some accounts were recorded by tribe members themselves. Though previously recounted by others, the Haudenosaunee creation story here is from Tuscarora tribal member David Cusick. A physician and artist, Cusick was one of the first Native American writers to preserve tribal history in his Sketches of the Ancient History of the Six Nations (1826). The Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address comes from University of Victoria professor Gerald Taiaiake Alfred, a member of the Kahnawake (Mohawk) tribe. Alfred has published several works about Native American culture in the early 21st century.

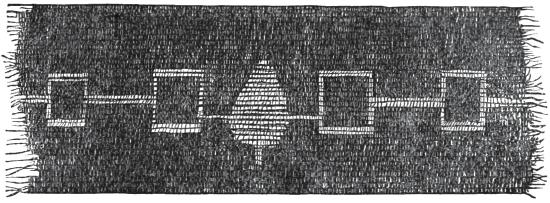

Image 1.2 | Wampum Belt Commemorating the Iroquis Confederacy Artist | Unknown Source | Wikimedia Commons License | Public Domain

1.3.1 Creation Story (Haudenosaunee (Iroquois))

In the great past, deep water covered all the earth. The air was filled with birds, and great monsters were in possession of the waters, when a beautiful woman was seen by them falling from the sky. Then huge ducks gathered in council and resolved to meet this wonderful creature and break the force of her fall. So they arose, and, with pinion overlapping pinion, unitedly received the dusky burden.

Then the monsters of the deep also gathered in council to decide which should hold this celestial being and protect her from the terrors of the water, but none was able except a giant tortoise, who volunteered to endure this lasting weight upon his back.

There she was gently placed, while he, constantly increasing in size, soon became a large island. Twin boys were after a time brought forth by the woman—one the spirit of good, who made all good things, and caused the maize, fruit, and tobacco to grow; the other the spirit of evil, who created the weeds and all vermin. Ever the world was increasing in size, although occasional quakings were felt, caused by the efforts of the monster tortoise to stretch out, or by the contraction of his muscles.

After the lapse of ages from the time of his general creation Ta-rhuⁿ-hiă-wăh-kuⁿ, the Sky Holder, resolved upon a special creation of a race which should surpass all others in beauty, strength, and bravery; so from the bosom of the great island, where they had previously subsisted upon moles, Ta-rhuⁿ-hiă-wăh-kuⁿ brought out the six pairs, which were destined to become the greatest of all people.

The Tuscaroras tell us that the first pair were left near a great river, now called the Mohawk. The second family were directed to make their home by the side of a big stone. Their descendants have been termed the Oneidas. Another pair were left on a high hill, and have ever been called the Onondagas. Thus each pair was left with careful instructions in different parts of what is now known as the State of New York, except the Tuscaroras, who were taken up the Roanoke River into North Carolina, where Ta-rhuⁿ-hiă-wăh-kuⁿ also took up his abode, teaching them many useful arts before his departure. This, say they, accounts for the superiority of the Tuscaroras. But each of the six tribes will tell you that his own was the favored one with whom Sky Holder made his terrestrial home, while the Onondagas claim that their possession of the council fire prove them to have been the chosen people.

Later, as the numerous families became scattered over the State, some lived in localities where the bear was the principal game, and were called from that circumstance the clan of the Bear. Others lived where the beavers were trapped, and they were called the Beaver clan. For similar reasons the Snipe, Deer, Wolf, Tortoise, and Eel clans received their appellations.

1.3.2 How the World Was Made (Cherokee)

The earth is a great floating island in a sea of water. At each of the four corners there is a cord hanging down from the sky. The sky is of solid rock. When the world grows old and worn out, the cords will break, and then the earth will sink down into the ocean. Everything will be water again. All the people will be dead. The Indians are much afraid of this.

In the long time ago, when everything was all water, all the animals lived up above in Galun’lati, beyond the stone arch that made the sky. But it was very much crowded. All the animals wanted more room. The animals began to wonder what was below the water and at last Beaver’s grandchild, little Water Beetle, offered to go and find out. Water Beetle darted in every direction over the surface of the water, but it could find no place to rest. There was no land at all. Then Water Beetle dived to the bottom of the water and brought up some soft mud. This began to grow and to spread out on every side until it became the island which we call the earth. Afterwards this earth was fastened to the sky with four cords, but no one remembers who did this.

At first the earth was flat and soft and wet. The animals were anxious to get down, and they sent out different birds to see if it was yet dry, but there was no place to alight; so the birds came back to Galun’lati. Then at last it seemed to be time again, so they sent out Buzzard; they told him to go and make ready for them.

This was the Great Buzzard, the father of all the buzzards we see now. He flew all over the earth, low down near the ground, and it was still soft. When he reached the Cherokee country, he was very tired; his wings began to flap and strike the ground. Wherever they struck the earth there was a valley; whenever the wings turned upwards again, there was a mountain. When the animals above saw this, they were afraid that the whole world would be mountains, so they called him back, but the Cherokee country remains full of mountains to this day. [This was the original home, in North Carolina.]

When the earth was dry and the animals came down, it was still dark.

Therefore they got the sun and set it in a track to go every day across the island from east to west, just overhead. It was too hot this way. Red Crawfish had his shell scorched a bright red, so that his meat was spoiled. Therefore the Cherokees do not eat it.

Then the medicine men raised the sun a handsbreadth in the air, but it was still too hot. They raised it another time; and then another time; at last they had raised it seven handsbreadths so that it was just under the sky arch. Then it was right and they left it so. That is why the medicine men called the high place “the seventh height.” Every day the sun goes along under this arch on the under side; it returns at night on the upper side of the arch to its starting place.

There is another world under this earth. It is like this one in every way. The animals, the plants, and the people are the same, but the seasons are different.

The streams that come down from the mountains are the trails by which we reach this underworld. The springs at their head are the doorways by which we enter it.

But in order to enter the other world, one must fast and then go to the water, and have one of the underground people for a guide. We know that the seasons in the underground world are different, because the water in the spring is always warmer in winter than the air in this world; and in summer the water is cooler.

We do not know who made the first plants and animals. But when they were first made, they were told to watch and keep awake for seven nights. This is the way young men do now when they fast and pray to their medicine. They tried to do this.

The first night, nearly all the animals stayed awake. The next night several of them dropped asleep. The third night still more went to sleep. At last, on the seventh night, only the owl, the panther, and one or two more were still awake. Therefore, to these were given the power to see in the dark, to go about as if it were day, and to kill and eat the birds and animals which must sleep during the night.

Even some of the trees went to sleep. Only the cedar, the pine, the spruce, the holly, and the laurel were awake all seven nights. Therefore they are always green.

They are also sacred trees. But to the other trees it was said, “Because you did not stay awake, therefore you shall lose your hair every winter.”

After the plants and the animals, men began to come to the earth. At first there was only one man and one woman. He hit her with a fish. In seven days a little child came down to the earth. So people came to the earth. They came so rapidly that for a time it seemed as though the earth could not hold them all.

1.3.3 Talk Concerning the First Beginning (Zuni)

Yes, indeed. In this world there was no one at all. Always the sun came up; always he went in. No one in the morning gave him sacred meal; no one gave him prayer sticks; it was very lonely. He said to his two children: “You will go into the fourth womb. Your fathers, your mothers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, all the society priests, society ̂pekwins, society bow priests, you will bring out yonder into the light of your sun father.” Thus he said to them. They said,

“But how shall we go in?” “That will be all right.” Laying their lightning arrow across their rainbow bow, they drew it. Drawing it and shooting down, they entered.

When they entered the fourth womb it was dark inside. They could not distinguish anything. They said, “Which way will it be best to go?” They went toward the west. They met someone face to face. They said, “Whence come you?”

“I come from over this way to the west.” “What are you doing going around?” “I am going around to look at my crops. Where do you live?” “No, we do not live any place. There above our father the Sun, priest, made us come in. We have come in,” they said. “Indeed,” the younger brother said. “Come, let us see,” he said.

They laid down their bow. Putting underneath some dry brush and some dry grass that was lying about, and putting the bow on top, they kindled fire by hand.

When they had kindled the fire, light came out from the coals. As it came out, they blew on it and it caught fire. Aglow! It is growing light. “Ouch! What have you there?” he said. He fell down crouching. He had a slimy horn, slimy tail, he was slimy allover, with webbed hands. The elder brother said, “Poor thing! Put out the light.” Saying thus, he put out the light. The youth said, “Oh dear, what have you there?” “Why, we have fire,” they said. “Well, what (crops) do you have coming up?” “Yes, here are our things coming up.” Thus he said. He was going around looking after wild grasses.

He said to them, “Well, now, let us go.” They went toward the west, the two leading. There the people were sitting close together. They questioned one another.

Thus they said, “Well, now, you two, speak. I think there is something to say. It will not be too long a talk. If you lotus know that we shall always remember it.” “That is so, that is so,” they said. “Yes, indeed, it is true. There above is our father, Sun.

No one ever gives him prayer sticks; no one ever gives him sacred meal; no one ever gives him shells. Because it is thus we have come to you, in order that you may go out standing yonder into the daylight of your sun father. Now you will say which way (you decide).” Thus the two said. “Hayi! Yes, indeed. Because it is thus you have passed us on our roads. Now that you have passed us on our roads here where we stay miserably, far be it from us to speak against it. We can not see one another. Here inside where we just trample on one another, where we just spit on one another, where we just urinate on one another, where we just befoul one another, where we just follow one another about, you have passed us on our roads.

None of us can speak against it. But rather, as the priest of the north says, so let it be. Now you two call him.” Thus they said to the two, and they came up close toward the north side.

They met the north priest on his road. “You have come,” he said. “Yes, we have come. How have you lived these many days?” “Here where I live happily you have passed me on my road. Sit down.” When they were seated he questioned them.

“Now speak. I think there is something to say. It will not be too long a talk. So now, that you will let me know.” “Yes, indeed, it is so. In order that you may go out standing there into the daylight of your sun father we have passed you on your road.

However you say, so shall it be.” “Yes, indeed, now that you have passed us on our road here where we live thus wretchedly, far be it from me to talk against it. Now that you have come to us here inside where, we just trample on one another, where we just spit on one another, where we just urinate on one another, where we just befoul one another, where we just follow one another about, how should I speak against it?” so he said. Then they arose. They came back. Coming to the village where they were sitting in the middle place, there they questioned one another.

“Yes, even now we have met on our roads. Indeed there is something to say; it will not be too long a talk. When you let me know that, I shall always remember it,”

thus they said to one another. When they had spoken thus, “Yes, indeed. In order that you may go out standing into the daylight of your sun father, we have passed you on your road,” thus they said. “Hayi! Yes, indeed. Now that you have passed us on our road here where we cannot see one another, where we just trample on one another, where we just urinate on one another, where we just befoul one another, where we just follow one another around, far be it from me to speak against it. But rather let it be as my younger brother, the priest of the west shall say. When he says, ‘Let it be thus,’ that way it shall be. So now, you two call him.” Thus said the priest of the north and they went and stood close against the west side.

“Well, perhaps by means of the thoughts of someone somewhere it may be that we shall go out standing into the daylight of our sun father.” Thus he said.

The two thought. “Come, let us go over there to talk with eagle priest.” They went.

They came to where eagle was staying. “You have come.” “Yes.” “Sit down.” They sat down. “Speak!” “We want you.” “Where?” “Near by, to where our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, stay quietly, we summon you.” “Haiyi!” So they went. They came to where käeto·-we stayed. “Well, even now when you summoned me, I have passed you on your roads. Surely there is something to say; it will not be too long a talk. So now if you let me know that I shall always remember it,” thus he said. “Yes, indeed, it is so. Our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, all the society priests shall go out standing into the daylight of their sun father. You will look for their road.” “Very well,” he said, “I am going,” he said. He went around.

Coming back to his starting place he went a little farther out. Coming back to his starting place again he went still farther out. Coming back to his starting place he went way far out. Coming back to his starting place, nothing was visible. He came.

To where käeto·-we stayed he came. After he sat down they questioned him. “Now you went yonder looking for the road going out. What did you see in the world?”

“Nothing was visible.” “Haiyi!” “Very well, I am going now.” So he went.

When he had gone the two thought. “Come, let us summon our grandson, cokäpiso,” thus they said. They went. They came to where cokäpiso stayed. “Our grandson, how have you lived these days?” “Where I live happily you have passed me on my road. I think perhaps there is something to say; it will not be too long a talk. So now when you let me know that, I shall always remember it,” thus he said.

“Yes, indeed, it is so. Our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, all the society priests are about to come outstanding into the daylight of their sun father. We summon you that you may be the one to look for their road.” “Indeed?”

Thus he said. They went. When they got there, they questioned them where they were sitting. “Even now you have summoned me. Surely there is something to say; it will not be too long a talk. So now when you let me know that, I shall always remember it.” “Yes, indeed, it is so. When our fathers, our mothers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, the society priests, go forth standing into the daylight of their sun father, you will look for their road.” Thus the two said. He went out to the south. He went around. Coming back to the same place, nothing was visible. A second time he went, farther out. Coming back to the same place, nothing was visible. A third time, still farther out he went. Nothing was visible.

A fourth time he went, way far, but nothing was visible. When he came to where käeto·-we were staying, the two questioned him. “Now, our grandson, way off yonder you have gone to see the world. What did you see in the world?” Thus the two asked him. “Well, nothing was visible.” “Well indeed?” the two said. “Very well, I am going now.” Saying this, he went.

When cokäpiso had gone the two thought. “Come, let us go and talk to our grandson chicken hawk.” Thus they said. They went. They reached where chicken hawk stayed. “You have come.” “Yes.” “Sit down.” “How have you lived these days?”

“Happily. Well now, speak. I think there is something to say; it will not be too long a talk. So now, when you let me know it, I shall always remember that.” “Yes, indeed, it is so. When our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, the society priests, go out standing into the sunlight of their sun father, you will look for their road.” So they went. When they got there they sat down. There he questioned them. “Yes, even now you summoned me. Perhaps there is something to say; it will not be too long a talk. When you let me know that, I shall always remember it.” Thus he said. “Yes, indeed, it is so. When our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, the society priests, go out standing into the daylight of their sun father, you will look for their road.” “Is that so?” Saying this, he went out. He went to the south. He went where cokäpiso had been. Coming back to his starting place, nothing was visible. A second time he went, farther out. He came back to his starting place, nothing was visible. He went a third time, along the shore of the encircling ocean. A fourth time farther out he went. He came back to his starting place. Nothing was visible. To where käeto·-we stayed he came.

“Nothing is visible.” “Haiyi!” Yes, so I am going.” “Well, go.” So he went.

Then the two thought. “Come on, let us summon our grandson,” thus they said.

They went. They came to where humming bird was staying. “You have come?”

“Yes, how have you lived these days?” “Where I live happily these days you have passed me on my road. Sit down.” When they had sat down: “Well, now, speak. I think there is something to say; it will not be too long a talk. So now if you let me know that, I shall always remember it.” “Yes, indeed, it is so. When our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, the society priests, go out standing into the daylight of their sun father, you shall be the one to look for their road; for that we have summoned you . . . .Is that so?” Saying this, they went. When they got there, he questioned them. “Well, even now you summoned me. Surely there is something to say. It will not be too long a talk. So now when you let me know that I shall always remember it.” Thus he said. “Yes, indeed, it is so. When our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, the society priests, go out into the daylight of their sun father, that you shall be the one to look for their road, for that we have summoned you.” Thus the two said. He went out toward the south.

He went on. Coming back to his starting place, nothing was visible. Farther out he went. Coming back to the same place, nothing was visible. Then for the third time he went. Coming back to the same place, nothing was visible. For the fourth time he went close along the edge of the sky. Coming back to the same place, nothing was visible. He came. Coming where käeto·-we were staying, “Nothing is visible.”

“Hayi!” “Yes. Well, I am going now.” “Very well, go.” He went.

The two said, “What had we better do now? That many different kinds of feathered creatures, the ones who go about without ever touching the ground, have failed.” Thus the two said. “Come, let us talk with our grandson, locust. Perhaps that one will have a strong spirit because he is like water.” Thus they said. They went. Their grandson, locust, they met. “You have come.” “Yes, we have come.”

“Sit down. How have you lived these days?” “Happily.” “Well, even now you have passed me, on my road. Surely there is something to say; it will not be too long a talk. So now when you let me know that, that I shall always remember.” Thus he said. “Yes, indeed, it is so. In order that our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, the society priests, may go out standing into the daylight of their sun father, we have come to you.” “Is that so?” Saying this, they went.

When they arrived they sat down. Where they were sitting, he questioned them.

“Well, just now you came to me. Surely there is something to say; it will not be too long a talk. So now if you let me know that, that I shall always remember.” “Yes, indeed. In order that our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, the society priests, may go out standing into the daylight of their sun father, we have summoned you.” “Indeed?” Saying this, locust rose right up. He goes up. He went through into another world. And again he goes right up. He went through into another world. And again he goes right up. Again he went through into another world. He goes right up. When he had just gone a little way his strength gave out, he came back to where käeto·-we were staying and said, “Three times I went through and the fourth time my strength gave out.” “Hayi! Indeed?” Saying this, he went.

When he had gone the two thought. “Come, let us speak with our grandson, Reed Youth. For perhaps that one with his strong point will be all right.” Saying this, they went. They came to where Reed Youth stayed. “You have come?” “Yes; how have you lived these days.” “Where I stay happily you have passed me on my road.

Sit down.” Thus he said. They sat down. Then he questioned them. “Yes. Well, even now you have passed me on my road. I think there is something to say; it will not be too long a talk. When you let me know that, that I shall always remember.” Thus he said. “Yes, indeed, in order that our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, the society priests, may go out standing into the daylight of their sun father, we have come to you.” “Hayi! Is that so?” Having spoken thus, they went.

When they arrived they sat down. There he questioned them. “Yes, even now that you have summoned me I have passed you on your roads. Surely there is something to say; it will not be too long a talk. When you let me know that, that I shall always remember . . . . Yes, indeed, it is so. In order that our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, the society priests, may go forth standing into the daylight of their sun father, we have summoned you.” Thus they said. “Hayi! Is that so?”

Saying this, he went out. Where Locust had gone out he went out. The first time he passed through, the second time he passed through, the third time he passed through. Having passed through the fourth time and come forth standing into the daylight of his sun father, he went back in. Coming back in he came to where käeto·-we were staying. “You have come?” Thus they said. “Yes,” he said. “Far off to see what road there may be you have gone. How may it be there now?” Thus they said. “Yes, indeed, it is so. There it is as you wanted it. As you wished of me, I went forth standing into the daylight of my sun father now.” Thus he said. “Halihi!

Thank you!” “Now I am going.” “Go.” Saying this, he went.

After he had gone they were sitting around. Now as they were sitting around, there the two set up a pine tree for a ladder. They stayed there. For four days they stayed there. Four days, they say, but it was four years. There all the different society priests sang their song sequences for one another. The ones sitting in the first row listened carefully. Those sitting next on the second row heard all but a little. Those sitting on the third row heard here and there. Those sitting last on the fourth row heard just a little bit now and then. It was thus because of the rustling of the dry weeds.

When their days there were at an end, gathering together their sacred things they arose. “Now what shall be the name of this place?” “Well, here it shall be sulphur-smell-inside-world; and furthermore, it shall be raw-dust world.” Thus they said. “Very well. Perhaps if we call it thus it will be all right.” Saying this, they came forth.

After they had come forth, setting down their sacred things in a row at another place, they stayed there quietly. There the two set up a spruce tree as a ladder.

When the ladder was up they stayed there for four days. And there again the society priests sang their song sequences for one another. Those sitting on the first row listened carefully. Those sitting there on the second row heard all but a little. Those sitting there on the third row heard here and there. Those sitting last distinguished a single word now and then. It was thus because of the rustling of some plants. When their days there were at an end, gathering together their sacred things there they arose. “Now what shall it be called here?” “Well, here it shall be called soot-inside-world, because we still can not recognize one another.” “Yes, perhaps if it is called thus it will be all right.” Saying this to one another, they arose.

Passing through to another place, and putting down their sacred things in a row, they stayed there quietly. There the two set up a piñon tree as a ladder. When the piñon tree was put up, there all the society priests and all the priests went through their song sequences for one another. Those sitting in front listened carefully.

Those sitting on the second row heard all but a little. Those sitting behind on the third row heard here and there. Those sitting on the fourth row distinguished only a single word now and then. This was because of the rustling of the weeds.

When their days there were at an end, gathering together their sacred things they arose. Having arisen, “Now what shall it be called here?” “Well, here it shall be fog-inside-world, because here just a little bit is visible.” “Very well, perhaps if it is called thus it will be all right.” Saying this, rising, they came forth.

Passing through to another place, there the two set down their sacred things in a row, and there they sat down. Having sat down, the two set up a cottonwood tree as a ladder. Then all the society priests and all the priests went through their song sequences for one another. Those sitting first heard everything clearly. Those sitting on the second row heard all but a little. Those sitting on the third row heard here and there. Those sitting last on the fourth row distinguished a single word now and then. It was thus because of the rustling of some plants.

When their days there were at an end, after they had been there, when their four days were passed, gathering together their sacred possessions, they arose.

When they arose, “Now what shall it be called here?” “Well, here it shall be wing-inner-world, because we see our sun father’s wings.” Thus they said. They came forth.

Into the daylight of their sun father they came forth standing. Just at early dawn they came forth. After they had come forth there they set down their sacred possessions in a row. The two said, “Now after a little while when your sun father comes forth standing to his sacred place you will see him face to face. Do not close your eyes.” Thus he said to them. After a little while the sun came out. When he came out they looked at him. From their eyes the tears rolled down. After they had looked at him, in a little while their eyes became strong. “Alas!” Thus they said. They were covered all over with slime. With slimy tails and slimy horns, with webbed fingers, they saw one another. “Oh dear! is this what we look like?” Thus they said.

Then they could not tell which was which of their sacred possessions.

Meanwhile, near by an old man of the Dogwood clan lived alone. Spider said to him, “Put on water. When it gets hot, wash your hair.” “Why?” “Our father, our mothers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, all the society priests, into the daylight of their sun father have come forth standing. They can not tell which is which. You will make this plain to them.” Thus she said. “Indeed? Impossible.

From afar no one can see them. Where they stay quietly no one can recognize them.” Thus he said. “Do not say that. Nevertheless it will be all right. You will not be alone. Now we shall go.” Thus she said. When the water was warm he washed his hair.

Meanwhile, while he was washing his hair, the two said, “Come let us go to meet our father, the old man of the Dogwood clan. I think he knows in his thoughts; because among our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, we can not tell which is which.” Thus they said. They went. They got there. As they were climbing tip, “Now indeed! They are coming.” Thus Spider said to him. She climbed up his body from his toe. She clung behind his ear. The two entered. “You have come,” thus he said. “Yes. Our father, how have you lived these days?” “As I live happily you pass me on my road. Sit down.” They sat down.

“Well, now, speak. I think some word that is not too long, your word will be.

Now, if you let me know that, remembering it, I shall live.” “Indeed it is so. Our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, all the society priests, into the daylight of their sun father have risen and come out. It is not plain which is which. Therefore we have passed you on your road.” “Haiyi, is that so? Impossible!

From afar no one can see them. Where they stay quietly no one can recognize them.” Thus he said. “Yes, but we have chosen you.” Thus the two said. They went.

When they came there, “My fathers, my mothers, how have you lived these days?”

“Happily, our father, our child. Be seated.” Thus they said. He sat down. Then he questioned them. “Yes, now indeed, since you have sent for me, I have passed you on your road. I think some word that is not too long your word will be. Now if you let me know that, remembering it, I shall always live.”

Thus he said. “Indeed, it is so. Even though our fathers, our mothers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, łhe·-eto-we, have come out standing into the daylight of their sun father, it is not plain which of these is which. Therefore we have sent for you.” Thus they said. “Haiyi. Well, let me try.” “Impossible. From afar no one can see them. Where they stay quietly no one can tell which is which.” “Well, let me try.”

Thus he said. Where they lay in a row he stood beside them. Spider said to him,

“Here, the one that lies here at the end is käeto·-we and these next ones touching it are tcu-eto·we, and this next one is łhe·-eto-we, and these next ones touching it are mu-eto·we.” Thus she said. He said, “Now this is käeto·-we, and these all touching it are tcu-eto·we, and this one is łhe·-eto-we, and all these touching it are mu-eto·we.” Thus he said. “Halihi! Thank you. How shall be the cycle of the months for them?” Thus he said: “This one Branches-broken-down. This one No-snow-on-the-road. This one Little-sand-storms. This one Great-sand-storms. This the Month-without-a-name. This one Turn-about. This one Branches-broken-down.

This one No-snow-on-the-road. This one Little-sand-storms. This one Great-sand-storms. This the Month-without-a-name. This one Turn-about. Thus shall be all the cycle of the months.” “Halihi! Thank you. Our father, you shall not be poor. Even though you have no sacred possessions toward which your thoughts bend, whenever Itiwana is revealed to us, because of your thought, the ceremonies of all these shall come around in order. You shall not be a slave.” This they said.

They gave him the sun. “This shall be your sacred possession.” Thus they said.

When this had happened thus they lived.

Four days—four days they say, but it was four years—there they stayed.

When their days were at an end, the earth rumbled. The two said, “Who was left behind?” “I do not know, but it seems we are all here.” Thus they said. Again the earth rumbled. “Well, does it not seem that some one is still left behind?” Thus the two said. They went. Coming to the place where they had come out, there they stood. To the mischief-maker and the Mexicans they said, “Haiyi! Are you still left behind?” “Yes.” “Now what are you still good for?” Thus they said. “Well, it is this way. Even though käeto·-we have issued forth into the daylight, the people do not live on the living waters of good corn; on wild grasses only they live. Whenever you come to the middle you will do well to have me. When the people are many and the land is all used up, it will not be well. Because this is so I have come out.” Thus he said. “Haiyi! Is that so? So that’s what you are. Now what are you good for?”

Thus they said. “Indeed, it is so. When you come to the middle, it will be well to have my seeds. Because käeto·-we do not live on the good seeds of the corn, but on wild grasses only. Mine are the seeds of the corn and all the clans of beans.” Thus he said. The two took him with them. They came to where käeto·-we were staying.

They sat down. Then they questioned him. “Now let us see what you are good for.”

“Well, this is my seed of the yellow corn.” Thus he said. He showed an ear of yellow corn. “Now give me one of your people.” Thus he said. They gave him a baby. When they gave him the baby it seems he did something to her. She became sick. After a short time she died. When she had died he said, “Now bury her.” They dug a hole and buried her. After four days he said to the two, “Come now. Go and see her.”

The two went to where they had come out. When they got there the little one was playing in the dirt. When they came, she laughed. She was happy. They saw her and went back. They came to where the people were staying. “Listen! Perhaps it will be all right for you to come. She is still alive. She has not really died.” “Well, thus it shall always be.” Thus he said.

Gathering together all their sacred possessions, they came hither. To the place called since the first beginning, Moss Spring, they came. There they set down their sacred possessions in a row. There they stayed. Four days they say, but it was four years. There the two washed them. They took from all of them their slimy tails, their slimy horns. “Now, behold! Thus you will be sweet.” There they stayed.

When their days were at an end they came hither. Gathering together all their sacred possessions, seeking Itiwana, yonder their roads went. To the place called since the first beginning Massed-cloud Spring, they came. There they set down their sacred possessions in a row. There they stayed quietly. Four days they stayed. Four days they say, but it was four years. There they stayed. There they counted up the days. For käeto·-we, four nights and four days. With fine rain caressing the earth, they passed their days. The days were made for łhe·-eto-we, mu-eto·we. For four days and four nights it snowed. When their days were at an end there they stayed.

When their days were at an end they arose. Gathering together all their sacred possessions, hither their roads went. To the place called since the first beginning Mist Spring their road came. There they sat down quietly. Setting out their sacred possessions in a row, they sat down quietly. There they counted up the days for one another. They watched the world for one another’s waters. For käeto·-we, four days and four nights, with heavy rain caressing the earth they passed their days. When their days were at an end the days were made for łhe·-eto-we and mu-eto·we. Four days and four nights with falling snow the world was filled. When their days were at an end, there they stayed.

When all their days were passed, gathering together all their sacred possessions, hither their road went. To Standing-wood Spring they came. There they sat down quietly. Setting out their sacred possessions in a row, they stayed quietly. There they watched one another’s days. For käeto·-we, four days and four nights with fine rain caressing the earth, they passed their days. When all their days were at an end, the days were made for lhe-eto:we and mu-eto·we. For four days and four nights, with falling snow, the world was filled. When all their days were at an end, there they stayed.

When all their days were passed, gathering together their sacred possessions, and arising, hither they came. To the place called since the first beginning Upuilima they came. When they came there, setting down their sacred possessions in a row, they stayed quietly. There they strove to outdo one another. There they planted all their seeds. There they watched one another’s days for rain. For käeto·-we, four days with heavy rain caressing the earth. There their corn matured. It was not palatable, it was bitter. Then the two said, “Now by whose will will our corn become fit to eat?” Thus they said. They summoned raven. He came and pecked at their corn, and it became good to eat. “It is fortunate that you have come.” With this then, they lived.

When their days were at an end they arose. Gathering together their sacred possessions, they came hither. To the place called since the first beginning, Cornstalk-place they came. There they set down their sacred possessions in a row.

There they stayed four days. Four days they say, but it was four years. There they planted all their seeds. There they watched one another’s days for rain. During käeto·-we’s four days and four nights, heavy rain fell. During lhe-eto:we’s and mu-eto·we’s four days and four nights, the world was filled with falling snow. Their days were at an end. Their corn matured. When it was mature it was hard. Then the two said, “By whose will will our corn become soft? Well, owl.” Thus they said.

They summoned owl. Owl came. When he came he pecked at their corn and it became soft.

Then, when they were about to arise, the two said, “Come, let us go talk to the corn priest.” Thus they said. They went. They came to where the corn priest stayed.

“How have you lived these days?” “As we are living happily you have passed us on our road. Sit down.” They sat down. There they questioned one another. “Well, speak. I think some word that is not too long, your word will be. Now, if you let me Page | 18

know that, remembering it, I shall always live.” “Indeed, it is so. To-morrow, when we arise, we shall set out to seek Itiwana. Nowhere have we found the middle.

Our children, our women, are tired. They are crying. Therefore we have come to you. Tomorrow your two children will look ahead. Perhaps if they find the middle when our fathers, our mothers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, lhe-eto:we, all the society priests, come to rest, there our children will rest themselves. Because we have failed to find the middle.” “Haiyi! Is that so? With plain words you have passed us on our road. Very well, then, thus it shall be.” Thus he said. The two went.

Next morning when they were about to set out they put down a split ear of corn and eggs. They made the corn priest stand up. They said, “Now, my children, some of you will go yonder to the south. You will take these.” Thus he said (indicating) the tip of the ear and the macaw egg. And then the ones that were to come this way took the base of the ear and the raven egg. Those that were to go to the south took the tip of the ear and the macaw egg. “Now, my children, yonder to the south you will go. If at any time you come to Itiwana, then some time we shall meet one another.” Thus they said. They came hither.

They came to the place that was to be Katcina village. The girl got tired. Her brother said, “Wait, sit down for a while. Let me climb up and look about to see what kind of a place we are going to.” Thus he said. His sister sat down. Her brother climbed the hill. When he had climbed up, he stood looking this way. “Eha! Maybe the place where we are going lies in this direction. Maybe it is this kind of a place.”

Thus he said and came down. Meanwhile his sister had scooped out the sand. She rested against the side of the hill. As she lay sleeping the wind came and raised her apron of grass. It blew up and she lay with her vulva exposed. As he came down he saw her. He desired her. He lay down upon his sister and copulated with her. His sister awoke. “Oh, dear, oh, dear,” she was about to say (but she said,) “Watsela, watsela.” Her brother said, “Ah!” He sat up. With his foot he drew a line. It became a stream of water. The two went about talking. The brother talked like Koyemci.

His sister talked like Komakatsik. The people came.

“Oh alas, alas! Our children have become different beings.” Thus they said.

The brother speaking: “Now it will be all right for you to cross here.” Thus he said.

They came and went in. They entered the river. Some of their children turned into water snakes.

Some of them turned into turtles. Some of them turned into frogs. Some of them turned into lizards. They bit their mothers. Their mothers cried out and dropped them. They fell into the river. Only the old people reached the other side. They sat down on the bank. They were half of the people. The two said, “Now wait. Rest here.” Thus they said. Some of them sat down to rest. The two said (to the others),

“Now you go in. Your children will turn into some kind of dangerous animals and will bite you. But even though you cry out, do not let them go. If, when you come out on the other side, your children do not again become the kind of creatures they are now, then you will throw them into the water.” Thus they said to them. They entered the water. Their children became different creatures and bit them. Even though they cried out, they crossed over. Then their children once more became the kind of creatures they had been. “Alas! Perhaps had we done that it would have been all right.” Now all had crossed over.

There setting down their sacred possessions in a row, they stayed quietly. They stayed there quietly for four days. Thus they say but they stayed for four years.

There each night they lived gaily with loud singing. When all their time was passed, the two said “Come, let us go and talk to Ne-we-kwe.” Thus they said. They went to where the Ne-we-kwe were staying. They came there. “How have you passed these days?’ “Happily. You have come? Be seated.” They sat down. Then they questioned them. “Now speak. I think some word that is not too long your word will be. If you let me know that, remembering it I shall always live.” “Indeed it is so. To-morrow we shall arise. Our fathers, our mothers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, lhe-eto:we, all the society priests, are going to seek the middle. But nowhere have we come to the middle. Our children and our women are tired. They are crying now. Therefore we have passed you on your road. To-morrow you will look ahead.

If perhaps somewhere you come to Itiwana there our children will rest.” Thus they said. “Alas! but we are just foolish people. If we make some mistake it will not be right.” Thus he said. “Well, that is of no importance. It can’t be helped. We have chosen you.” Thus they said. “Well indeed?’ “Yes. Now we are going.” “Go ahead.”

The two went out.

They came (to where the people were staying). “Come, let us go and speak to our children.” Thus they said. They went. They entered the lake. It was full of katcinas. “Now stand still a moment. Our two fathers have come.” Thus they said.

The katcinas suddenly stopped dancing. When they stopped dancing they said to the two, “Now our two fathers, now indeed you have passed us on our road. I think some word that is not too long your word will be. If you will let us know that we shall always remember it.” Thus he said. “Indeed it is so. Tomorrow we shall arise.

Therefore we have come to speak to you.” “Well indeed? May you go happily. You will tell our parents, ‘Do not worry.’ We have not perished. In order to remain thus forever we stay here. To Itiwana but one day’s travel remains. Therefore we stay nearby. When our world grows old and the waters are exhausted and the seeds are exhausted, none of you will go back to the place of your first beginning. Whenever the waters are exhausted and the seeds are exhausted you will send us prayer sticks.

Yonder at the place of our first beginning with them we shall bend over to speak to them. Thus there will not fail to be waters. Therefore we shall stay quietly near by.”

Thus they said to them. “Well indeed?” “Yes. You will tell my father, my mother, ‘Do not worry.’ We have not perished.” Thus they said. They sent strong words to their parents. “Now we are going. Our children, may you always live happily.” “Even thus may you also go.” Thus they said to the two. They went out. They arrived.

They told them. “Now our children, here your children have stopped. ‘They have perished,’ you have said. But no. The male children have become youths, and the females have become maidens. They are happy. They live joyously. They have sent you strong words. ‘Do not worry,’ they said.” “Haiyi! Perhaps it is so.”

They stayed overnight. Next morning they arose. Gathering together all their sacred possessions, they came hither. They came to Hanlhipingka. Meanwhile the two Ne-we-kwe looked ahead. They came to Rock-in-the-river. There two girls were washing a woolen dress. They killed them. After they had killed them they scalped them. Then someone found them out. When they were found out, because they were raw people, they wrapped themselves in mist. There to where käeto·-we were staying they came. “Alack, alas! We have done wrong!” Thus they said. Then they set the days for the enemy. There they watched one another’s days for rain. käeto·-we’s four days and four nights passed with the falling of heavy rain. There where a waterfall issued from a cave the foam arose. There the two Ahaiyute appeared. They came to where käeto·-we were staying. Meanwhile, from the fourth inner world, Unasinte, Uhepololo, Kailuhtsawaki, Hattungka, Oloma, Catunka, came out to sit down in the daylight. There they gave them the comatowe Song cycle. Meanwhile, right there, Coyote was going about hunting. He gave them their pottery drum. They sang comatowe.

After this had happened, the two said, “Now, my younger brother, Itiwana is less than one day distant. We shall gather together our children, all the beast priests, and the winged creatures, this night.” They went. They came yonder to Comk?äkwe. There they gathered together all the beasts, mountain lion, bear, wolf, wild cat, badger, coyote, fox, squirrel; eagle, buzzard, cokapiso, chicken hawk, baldheaded eagle, raven, owl. All these they gathered together. Now squirrel was among the winged creatures, and owl was among the beasts. “Now my children, you will contest together for your sun father’s daylight. Whichever side has the ball, when the sun rises, they shall win their sun father’s daylight.” Thus the two said. “Indeed?” They went there. They threw up the ball. It fell on the side of the beasts. They hid it. After they had hidden it, the birds came one by one but they could not take it. Each time they paid four straws. They could not take it.

At this time it was early dawn. Meanwhile Squirrel was lying by the fireplace.

Thus they came one by one but they could not take it. Eagle said, “Let that one lying there by the fireplace go.” They came to him and said, “Are you asleep?” “No. I am not asleep.” “Oh dear! Now you go!” Thus they said. “Oh no, I don’t want to go,” he said. He came back. “The lazy one does not wish to.” Thus they said. Someone else went. Again they could not take it. Now it was growing light. “Let that one lying by the fireplace go.” Thus they said. Again Buzzard went. “Alas, my boy, you go.” “Oh, no, I don’t feel like it.” Thus he said. Again he went back. “He does not want to,”

he said. Again some one else went. Again they did not take it. Now it was growing light. Spider said to him, “Next time they come agree to go.” Thus she said. Then again they said, “Let that one lying by the fireplace go.” Thus they said; and again someone went. When he came there he said, “Alas, my boy, you go.” “All right, I shall go.” Thus he said and arose. As he arose Spider said to him, “Take that stick.”

He took up a stick, so short. Taking it, he went. Now the sun was about to rise. They came there. Spider said to him, “Hit those two sitting on the farther side.” Thus she said. Bang! He knocked them down. He laid them down. Then, mountain lion, who was standing right there, said, “Hurry up, go after it. See whether you can take it.”

Thus he said. Spider said to him, “Say to him, ‘Oh, no, I don’t want to take it.’ So she said.” “Oh, no, I don’t want to take it. Perhaps there is nothing inside. How should I take it? There is nothing in there.” “That is right. There is nothing in there. All my children are gathered together. One of them is holding it. If you touch the right one, you will take it.” “All right.” Now Spider is speaking: “No one who is sitting here has it. That one who goes about dancing, he is holding it.” Thus she said. He went. He hit Owl on the hand. The white ball came out. He went. He took up the hollow sticks and took them away with him. Now the birds hid the ball. Spider came down. Over all the sticks she spun her web. She fastened the ball with her web. Now the animals came one by one. Whenever they touched a stick, she pulled (the ball) away. Each time they paid ten straws. The sun rose. After sunrise, he was sitting high in the sky. Then the two came. They said, “Now, all my children, you have won your sun father’s daylight, and you, beasts, have lost your sun father’s daylight. All day you will sleep. After sunset, at night, you will go about hunting. But you, owl, you have not stayed among the winged creatures. Therefore you have lost your sun father’s daylight. You have made a mistake. If by daylight, you go about hunting, the one who has his home above will find you out. He will come down on you. He will scrape off the dirt from his earth mother and put it upon you. Then thinking, ‘Let it be here,’ you will come to the end of your life. This kind of creature you shall be.” Thus they said. They stayed there overnight. The animals all scattered.

The two went. They came to where käeto·-we were staying. Then they arose.

Gathering together all their sacred possessions, they arose. Lhe-eto:we said, “Now, my younger brothers, hither to the north I shall take my road. Whenever I think that Itiwana has been revealed to you, then I shall come to you.” Thus he said, and went to the north. Now some woman, seeing them, said, “Oh dear! Whither are these going?” Thus she said:

Naiye heni aiye

Naiye heni aiye.

In white stripes of hail they went.

Meanwhile käeto·-we came hither. They came to House Mountain. When they came there they would not let them pass through. They fought together. A giant went back and forth before them. Thus they fought together. Thus evening came.

In the evening they came back to Hanlhipingka. Next day they went again. In heavy rain they fought together. In the evening they went back again. Next morning they went again for the third time. Again they fought together. The giant went back and forth in front. Even though she had arrows sticking in her body she did not die. At sunset they went back again. Next morning they went. They came there, and they fought together. Still they would not surrender. The giant went back and forth in front. Although she was wounded with arrows, she would not surrender. Ahaiyute said, “Alas, why is it that these people will not let us pass? Wherever may her heart be, that one that goes back and forth? Where her heart should be we have struck her, yet she does not surrender. It seems we can not overcome her. So finally go up to where your father stays. Without doubt he knows.” Thus he said. His younger brother climbed up to where the sun was.

It was nearly noon when he arrived. “You have come?” “Yes, I have come.”

“Very well, speak. I think some word that is not too long your word will be. So if you let me know that, I shall always remember it.” Thus he said. “Indeed, it is so. Our fathers, our mothers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, lhe-eto:we, all the society priests, have issued forth into the daylight. Here they go about seeking Itiwana. These people will not let them pass. Where does she have her heart, that one who goes back and forth before them? In vain have we struck her where her heart should be. Even though the arrows stick in her body, she does not surrender.”

“Haiyi! For nothing are you men! She does not have her heart in her body. In vain have you struck her there. Her heart is in her rattle.” Thus he said. “This is for you and this is for your elder brother.” Thus he said, and gave him two turquoise rabbit sticks. “Now, when you let these go with my wisdom I shall take back my weapons.’

“Haiyi! Is that so? Very well, I am going now.” “Go ahead. May you go happily.”

Thus he said. He came down. His elder brother said to him, “Now, what did he tell you?” “Indeed, it is so. In vain do we shoot at her body. Not there is her heart; but in her rattle is her heart. With these shall we destroy her.” Thus he said, and gave his brother one of the rabbit sticks. When he had given his brother the rabbit stick,

“Now go ahead, you.” Thus he said. The younger brother went about to the right. He threw it and missed. Whiz! The rabbit stick went up to the sun. As the rabbit stick came up the sun took it. “Now go ahead, you try.” Thus he said. The elder brother went around to the left. He threw it. As he threw it, zip! His rabbit stick struck his rattle. Tu --- n! They ran away. As they started to run away, their giant died. Then they all ran away. The others ran after them. They came to a village. They went into the houses. “This is my house;” “This is my house;” and “This is mine.” Thus they said. They went shooting arrows into the roof. Wherever they first came, they went in. An old woman and a little boy this big and a little girl were inside.

In the center of their room was standing a jar of urine. They stuffed their nostrils with känaite flowers and with cotton wool. Then they thrust their noses into the jar. The people could see them. “Oh, dear! These are ghosts!” Thus they said. Then the two said to them, “Do not harm them, for I think they know something. So even though it is dangerous they are still alive.” Thus they said. The two entered. As they came in they questioned them. “And now do you know something? Therefore, even though it is dangerous, you have not perished.” “Well, we have a sacred object.”

“Indeed! Very well, take them. We shall go. Your fathers, your mothers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, lhe-eto:we, you will pass on their roads. If your days are the same as theirs you will not be slaves. It does not matter that he is only a little boy. Even so, he will be our father. It does not matter that she is a little girl, she will be our mother.” Thus he said. Taking their sacred object they went. They came to where käeto·-we were staying. There they said to them, “Now make your days.”

“Oh, no! We shall not be first. When all your days are at an end, then we shall add on our days.” Thus they said. Then they worked for käeto·-we. käeto·-we’s days were made. Four days and four nights, with fine rain falling, were the days of käeto·-we. When their days were at an end, the two children and their grandmother worked. Their days were made. Four days and four nights, with heavy rain falling, were their days. Then they removed the evil smell. They made flowing canyons.

Then they said, “Halihi! Thank you! Just the same is your ceremony. What may your clan be?” “Well, we are of the Yellow Corn clan.” Thus they said. “Haiyi! Even though your eton:e is of the Yellow Corn clan, because of your bad smell, you have become black. Therefore you shall be the Black Corn clan.” Thus they said to them.

Then they arose. Gathering together all their sacred possessions, they came hither, to the place called, since the first beginning, Halona-Itiwana, their road came. There they saw the Navaho helper, little red bug. “Here! Wait! All this time we have been searching in vain for Itiwana. Nowhere have we seen anything like this.” Thus they said. They summoned their grandchild, water bug. He came.

“How have you lived these many days?” “Where we have been living happily you have passed us on our road. Be Seated.” Thus they said. He sat down. Then he questioned them. “Now, indeed, even now, you have sent for me. I think some word that is not too long your word will be. So now, if you will let me know that, I shall always remember it.” “Indeed, it is so. Our fathers, our mothers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, lhe-eto:we, all the society priests, having issued forth into the daylight, go about seeking the middle. You will look for the middle for them. This is well. Because of your thoughts, at your heart, our fathers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, lhe-eto:we, will sit down quietly. Following after those, toward whom our thoughts bend, we shall pass our days.” Thus they said. He sat down facing the east. To the left he stretched out his arm. To the right he stretched out his arm, but it was a little bent. He sat down facing the north. He stretched out his arms on both sides. They were just the same. Both arms touched the horizon.

“Come, let us cross over to the north. For on this side my right arm is a little bent.”

Thus he said. They crossed (the river). They rested. He sat down. To all directions he stretched out his arms. Everywhere it was the same. “Right here is the middle.”

Thus he said. There his fathers, his mothers, käeto·-we, tcu-eto·we, mu-eto·we, lhe-eto:we, all the society priests, the society p̂ekwins, the society bow priests, and all their children came to rest. Thus it happened long ago.

1.3.4 From the Winnebago Trickster Cycle

Trickster’s Warpath

https://hotcakencyclopedia.com/ho.TrickstersWarpath.html

Trickster Gets Pregnant

https://hotcakencyclopedia.com/ho.TricksterGetsPregnant.html

Trickster Eats a Laxative Bulb

https://hotcakencyclopedia.com/ho.TricksterEatsLaxative.html

1.3.5 Origin of Disease and Medicine (Cherokee)

In the old days quadrupeds, birds, fishes, and insects could all talk, and they and the human race lived together in peace and friendship. But as time went on the people increased so rapidly that their settlements spread over the whole earth and the poor animals found themselves beginning to be cramped for room. This was bad enough, but to add to their misfortunes man invented bows, knives, blowguns, spears, and hooks, and began to slaughter the larger animals, birds and fishes for the sake of their flesh or their skins, while the smaller creatures, such as the frogs and worms, were crushed and trodden upon without mercy, out of pure carelessness or contempt. In this state of affairs the animals resolved to consult upon measures for their common safety.

The bears were the first to meet in council in their townhouse in Kuwa´hĭ, the

“Mulberry Place,” and the old White Bear chief presided. After each in turn had made complaint against the way in which man killed their friends, devoured their flesh and used their skins for his own adornment, it was unanimously decided to begin war at once against the human race. Some one asked what weapons man used to accomplish their destruction. “Bows and arrows, of course,” cried all the bears in chorus. “And what are they made of?” was the next question. “The bow of wood and the string of our own entrails,” replied one of the bears. It was then proposed that they make a bow and some arrows and see if they could not turn man’s weapons against himself. So one bear got a nice piece of locust wood and another sacrificed himself for the good of the rest in order to furnish a piece of his entrails for the string.

But when everything was ready and the first bear stepped up to make the trial it was found that in letting the arrow fly after drawing back the bow, his long claws caught the string and spoiled the shot. This was annoying, but another suggested that he could overcome the difficulty by cutting his claws, which was accordingly done, and on a second trial it was found that the arrow went straight to the mark. But here the chief, the old White Bear, interposed and said that it was necessary that they should have long claws in order to be able to climb trees. “One of us has already died to furnish the bowstring, and if we now cut off our claws we shall all have to starve together. It is better to trust to the teeth and claws which nature has given us, for it is evident that man’s weapons were not intended for us.”

No one could suggest any better plan, so the old chief dismissed the council and the bears dispersed to their forest haunts without having concerted any means for preventing the increase of the human race. Had the result of the council been otherwise, we should now be at war with the bears, but as it is the hunter does not even ask the bear’s pardon when he kills one.

The deer next held a council under their chief, the Little Deer, and after some deliberation resolved to inflict rheumatism upon every hunter who should kill one of their number, unless he took care to ask their pardon for the offense. They sent notice of their decision to the nearest settlement of Indians and told them at the same time how to make propitiation when necessity forced them to kill one of the deer tribe. Now, whenever the hunter brings down a deer, the Little Deer, who is swift as the wind and can not be wounded, runs quickly up to the spot and bending over the blood stains asks the spirit of the deer if it has heard the prayer of the hunter for pardon. If the reply be “Yes” all is well and the Little Deer goes on his way, but if the reply be in the negative he follows on the trail of the hunter, guided by the drops of blood on the ground, until he arrives at the cabin in the settlement, when the Little Deer enters invisibly and strikes the neglectful hunter with rheumatism, so that he is rendered on the instant a helpless cripple. No hunter who has regard for his health ever fails to ask pardon of the deer for killing it, although some who have not learned the proper formula may attempt to turn aside the Little Deer from his pursuit by building a fire behind them in the trail.

Next came the fishes and reptiles, who had their own grievances against humanity. They held a joint council and determined to make their victims dream of snakes twining about them in slimy folds and blowing their fetid breath in their faces, or to make them dream of eating raw or decaying fish, so that they would lose appetite, sicken, and die. Thus it is that snake and fish dreams are accounted for.

Finally the birds, insects, and smaller animals came together for a like purpose, and the Grubworm presided over the deliberations. It was decided that each in turn should express an opinion and then vote on the question as to whether or not man should be deemed guilty. Seven votes were to be sufficient to condemn him.

One after another denounced man’s cruelty and injustice toward the other animals and voted in favor of his death. The Frog (walâśĭ) spoke first and said: “We must do something to check the increase of the race or people will become so numerous that we shall be crowded from off the earth. See how man has kicked me about because I’m ugly, as he says, until my back is covered with sores;” and here he showed the spots on his skin. Next came the Bird (tsiśkwa; no particular species is indicated), who condemned man because “he burns my feet off,” alluding to the way in which the hunter barbecues birds by impaling them on a stick set over the fire, so that their feathers and tender feet are singed and burned. Others followed in the same strain. The Ground Squirrel alone ventured to say a word in behalf of man, who seldom hurt him because he was so small; but this so enraged the others that they fell upon the Ground Squirrel and tore him with their teeth and claws, and the stripes remain on his back to this day.

The assembly then began to devise and name various diseases, one after another, and had not their invention finally failed them not one of the human race would have been able to survive. The Grubworm in his place of honor hailed each new malady with delight, until at last they had reached the end of the list, when some one suggested that it be arranged so that menstruation should sometimes prove fatal to woman. On this he rose up in his place and cried: “Watań Thanks!

I’m glad some of them will die, for they are getting so thick that they tread on me.”

He fairly shook with joy at the thought, so that he fell over backward and could not get on his feet again, but had to wriggle off on his back, as the Grubworm has done ever since.

When the plants, who were friendly to man, heard what had been done by the animals, they determined to defeat their evil designs. Each tree, shrub, and herb, down even to the grasses and mosses, agreed to furnish a remedy for some one of the diseases named, and each said: “I shall appear to help man when he calls upon me in his need.” Thus did medicine originate, and the plants, every one of which has its use if we only knew it, furnish the antidote to counteract the evil wrought by the revengeful animals. When the doctor is in doubt what treatment to apply for the relief of a patient, the spirit of the plant suggests to him the proper remedy.

1.3.6 Thanksgiving Address (Haudenosaunee (Iroquois))

https://americanindian.si.edu/environment/pdf/01_02_Thanksgiving_Address.pdf

1.3.7 The Arrival of the Whites (Lenape (Delaware))

https://www.americanheritage.com/content/native-americans-first-view-whites-shore

1.3.8 The Coming of the Whiteman Revealed: Dream of the White Robe and Floating Island (Micmac)

When there were no people in this country but Indians, and before they knew of any others, a young woman had a singular dream. She dreamed that a small island came floating in towards the land, with tall trees on it and living beings, and amongst others a young man dressed in rabbit-skin garments. Next day she interpreted her dream and sought for an interpretation. it was the custom in those days, when any one had a remarkable dream, to consult the wise men and especially the magicians and soothsayers. These pondered over the girl’s dream, but they could make nothing of it; but next day an event occurred that explained it all. Getting up in the morning, what should they see but a singular little island, as they took it to be, which had drifted near to land, and had become stationery there.

There were trees on it, and branches to the trees, on which a number of bears, as they took them to be, were crawling about. They all seized their bows and arrows and spears and rushed down to the shore, intending to shoot the bears. What was their surprise to find that these supposed bears were men, and that some of them were lowering down into the water a very singular constructed canoe, into which several of them jumped and paddled ashore. Among them was a man dressed in white—a priest with his white stole on, who came towards them making signed of friendliness, raising his hand towards heaven and addressing them in an earnest manner, but in a language which they could not understand. The girl was now questioned respecting her dream. “was it such an island as this that she had seen?

was this the man?” She affirmed that they were indeed the same. Some of them, especially the necromancers, were displeased. They did not like it that the coming of the foreigners should have been intimated to this young girl and not to them.

Had an enemy of the Indian tribes, with whom they were at war, been about about to make a descent upon them they could have foreseen and foretold it by th epoer of their magic. But of the coming of this teacher of a new religion they could know nothing. The new teacher was gradually received into favor, though the magicians opposed him. The ep[;e received his instructions and submitted to the rite of baptism. The priest learned their tongue, and gave them the prayer-book written in what they call Abòotŭloveëgăsĭk—ornamental mark-writing, a mark standing for a word, and rendering it so difficult to learn that it may be said to be impossible.

And this was manifestly done for the purpose of keeping the Indians in ignorance.

Had their language been reduced to writing in the ordinary way, the Indians would have learned the use of writing an reading, and would have so advanced knowledge as to have been able to cope with their more enlightened invaders, and it would have been a more difficult matter for the latter to have cheated them out of their lands, etc.

Such was Josiah’s story. Whatever were the motives of the priests who gave them their pictorial writing, it is one of the grossest literary blunders that was ever perpetrated. it is bad enough for the Chinese, who language is said to be monosyllabic and unchanged by grammatical inflection. But Micmac is partly syllabic, “endless,” in its compounds and grammatical changes, and utterly incapable of being represented by signs.

1.3.9 Reading and Review Questions

1. In the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), Cerokee, and Zuni Origin Tales, what values of their respective tribes emerge in each tale? How?

2. In the Trickster Cycle, what is the cause of/who causes disruptions? Why? To what effect?

3. What concept of justice, if any, does “Origin of Disease and Medicine” illustrate? How?

4. What do you think is the overall message or purpose of the “Thanksgiving Address?” How does its refrain contribute to this message or purpose? Why?

5. What do “The Arrival of the Whites” and “The Coming of the Whiteman Revealed” suggest the Lenape (Delaware) and the Micmac clearly understood about the meaning of the white man’s arrival? What, if anything, about the white man’s arrival, is not understood? How do you know?