17.5: Literature in the Renaissance

- Page ID

- 91053

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Rise of the Vernacular

Renaissance literature refers to European literature that was influenced by the intellectual and cultural tendencies of the Renaissance.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Evaluate the influence of the different people, styles, and ideas that influenced Renaissance literature

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- In the 13th century, Italian authors began writing in their native vernacular language rather than in Latin, French, or Provençal. The earliest Renaissance literature appeared in 14th century Italy; Dante, Petrarch, and Machiavelli are notable examples of Italian Renaissance writers.

- From Italy the influence of the Renaissance spread across Europe; the scholarly writings of Erasmus and the plays of Shakespeare can be considered Renaissance in character.

- Renaissance literature is characterized by the adoption of a Humanist philosophy and the recovery of the classical literature of Antiquity, and benefited from the spread of printing in the latter part of the 15th century.

Key Terms

- Spenserian stanza: Fixed verse form invented by Edmund Spenser for his epic poem “The Faerie Queene.” Each stanza contains nine lines in total; the rhyme scheme of these lines is “ababbcbcc. “

- vernacular: The native language or native dialect of a specific population, especially as distinguished from a literary, national, or standard variety of the language.

- anthropocentric: Believing human beings to be the central or most significant species on the planet, or the assessing reality through an exclusively human perspective.

Overview

The 13th century Italian literary revolution helped set the stage for the Renaissance. Prior to the Renaissance, the Italian language was not the literary language in Italy. It was only in the 13th century that Italian authors began writing in their native vernacular language rather than in Latin, French, or Provençal. The 1250s saw a major change in Italian poetry as the Dolce Stil Novo (Sweet New Style, which emphasized Platonic rather than courtly love) came into its own, pioneered by poets like Guittone d’Arezzo and Guido Guinizelli. Especially in poetry, major changes in Italian literature had been taking place decades before the Renaissance truly began.

With the printing of books initiated in Venice by Aldus Manutius, an increasing number of works began to be published in the Italian language, in addition to the flood of Latin and Greek texts that constituted the mainstream of the Italian Renaissance. The source for these works expanded beyond works of theology and towards the pre-Christian eras of Imperial Rome and Ancient Greece. This is not to say that no religious works were published in this period; Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy reflects a distinctly medieval world view. Christianity remained a major influence for artists and authors, with the classics coming into their own as a second primary influence.

At Florence the most celebrated Humanists wrote also in the vulgar tongue, and commented on Dante and Petrarch and defended them from their enemies. Leone Battista Alberti, the learned Greek and Latin scholar, wrote in the vernacular, and Vespasiano da Bisticci, while he was constantly absorbed in Greek and Latin manuscripts, wrote the Vite di uomini illustri, valuable for their historical contents and rivaling the best works of the 14th century in their candor and simplicity.

Renaissance Literature

The earliest Renaissance literature appeared in 14th century Italy; Dante, Petrarch, and Machiavelli are notable examples of Italian Renaissance writers. From Italy the influence of the Renaissance spread at different rates to other countries, and continued to spread throughout Europe through the 17th century. The English Renaissance and the Renaissance in Scotland date from the late 15th century to the early 17th century. In northern Europe the scholarly writings of Erasmus, the plays of Shakespeare, the poems of Edmund Spenser, and the writings of Sir Philip Sidney may be considered Renaissance in character.

The literature of the Renaissance was written within the general movement of the Renaissance that arose in 13th century Italy and continued until the 16th century while being diffused into the western world. It is characterized by the adoption of a Humanist philosophy and the recovery of the classical literature of Antiquity and benefited from the spread of printing in the latter part of the 15th century. For the writers of the Renaissance, Greco-Roman inspiration was shown both in the themes of their writing and in the literary forms they used. The world was considered from an anthropocentric perspective. Platonic ideas were revived and put to the service of Christianity. The search for pleasures of the senses and a critical and rational spirit completed the ideological panorama of the period. New literary genres such as the essay and new metrical forms such as the sonnet and Spenserian stanza made their appearance.

The creation of the printing press (using movable type) by Johannes Gutenberg in the 1450s encouraged authors to write in their local vernacular rather than in Greek or Latin classical languages, widening the reading audience and promoting the spread of Renaissance ideas.

The impact of the Renaissance varied across the continent; countries that were predominantly Catholic or predominantly Protestant experienced the Renaissance differently. Areas where the Orthodox Church was culturally dominant, as well as those areas of Europe under Islamic rule, were more or less outside its influence. The period focused on self-actualization and one’s ability to accept what is going on in one’s life.

Renaissance Man (“Blister in the Sun” by the Violent Femmes): Quick overview of some of the prominent men of the Renaissance.

Renaissance Writers

The 13th and 14th century Italian literary revolution helped set the stage for the Renaissance.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Identify the key contributions made by Dante, Boccaccio, and Bruni

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- The ideas characterizing the Renaissance had their origin in late 13th century Florence, in particular in the writings of Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) and Petrarch (1304–1374).

- The literature and poetry of the Renaissance was largely influenced by the developing science and philosophy.

- The Humanist Francesco Petrarch, a key figure in the renewed sense of scholarship, was also an accomplished poet, publishing several important works of poetry in Italian as well as Latin.

- Petrarch’s disciple, Giovanni Boccaccio, became a major author in his own right, whose major work, The Decameron, was a source of inspiration and plots for many English authors in the Renaissance.

- A generation before Petrarch and Boccaccio, Dante Alighieri set the stage for Renaissance literature with his Divine Comedy, widely considered the greatest literary work composed in the Italian language and a masterpiece of world literature.

- Leonardo Bruni was an Italian humanist, historian, and statesman, often recognized as the first modern historian.

Key Terms

- humanist: One who studies classical antiquity and the intellectual adoption of its philosophies, centered on the important role of humans in the universe.

- metaphysics: A branch of philosophy concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world that encompasses it.

Overview

Many argue that the ideas characterizing the Renaissance had their origin in late 13th century Florence, in particular in the writings of Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) and Petrarch (1304–1374). Italian prose of the 13th century was as abundant and varied as its poetry. In the year 1282 a period of new literature began. With the school of Lapo Gianni, Guido Cavalcanti, Cino da Pistoia, and Dante Alighieri, lyric poetry became exclusively Tuscan. The whole novelty and poetic power of this school consisted in, according to Dante, Quando Amore spira, noto, ed a quel niodo Ch’ei detta dentro, vo significando—that is, in a power of expressing the feelings of the soul in the way in which love inspires them, in an appropriate and graceful manner, fitting form to matter, and by art fusing one with the other. Love is a divine gift that redeems man in the eyes of God, and the poet’s mistress is the angel sent from heaven to show the way to salvation.

The literature and poetry of the Renaissance was largely influenced by the developing science and philosophy. The Humanist Francesco Petrarch, a key figure in the renewed sense of scholarship, was also an accomplished poet, publishing several important works of poetry. He wrote poetry in Latin, notably the Punic War epic Africa, but is today remembered for his works in the Italian vernacular, especially the Canzoniere, a collection of love sonnets dedicated to his unrequited love, Laura. He was the foremost writer of sonnets in Italian, and translations of his work into English by Thomas Wyatt established the sonnet form in England, where it was employed by William Shakespeare and countless other poets.

Giovanni Boccaccio

Petrarch’s disciple, Giovanni Boccaccio, became a major author in his own right. His major work was The Decameron, a collection of 100 stories told by ten storytellers who have fled to the outskirts of Florence to escape the black plague over ten nights. The Decameron in particular and Boccaccio’s work in general were a major source of inspiration and plots for many English authors in the Renaissance, including Geoffrey Chaucer and William Shakespeare. The various tales of love in The Decameron range from the erotic to the tragic. Tales of wit, practical jokes, and life lessons contribute to the mosaic. In addition to its literary value and widespread influence, it provides a document of life at the time. Written in the vernacular of the Florentine language, it is considered a masterpiece of classical early Italian prose.

Boccaccio wrote his imaginative literature mostly in the Italian vernacular, as well as other works in Latin, and is particularly noted for his realistic dialogue that differed from that of his contemporaries, medieval writers who usually followed formulaic models for character and plot.

Discussions between Boccaccio and Petrarch were instrumental in Boccaccio writing the Genealogia deorum gentilium; the first edition was completed in 1360 and it remained one of the key reference works on classical mythology for over 400 years. It served as an extended defense for the studies of ancient literature and thought. Despite the Pagan beliefs at the core of the Genealogia deorum gentilium, Boccaccio believed that much could be learned from antiquity. Thus, he challenged the arguments of clerical intellectuals who wanted to limit access to classical sources to prevent any moral harm to Christian readers. The revival of classical antiquity became a foundation of the Renaissance, and his defense of the importance of ancient literature was an essential requirement for its development.

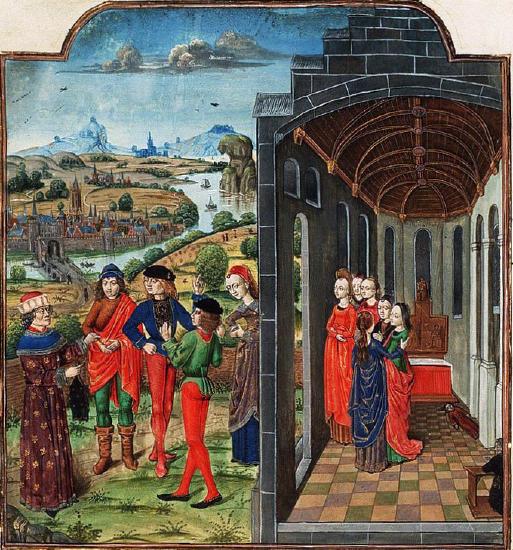

A depiction of Giovanni Boccaccio and Florentines who have fled from the plague, the frame story for The Decameron.

Dante Alighieri

A generation before Petrarch and Boccaccio, Dante Alighieri set the stage for Renaissance literature. His Divine Comedy, originally called Comedìa and later christened Divina by Boccaccio, is widely considered the greatest literary work composed in the Italian language and a masterpiece of world literature.

In the late Middle Ages, the overwhelming majority of poetry was written in Latin, and therefore was accessible only to affluent and educated audiences. In De vulgari eloquentia (On Eloquence in the Vernacular), however, Dante defended use of the vernacular in literature. He himself would even write in the Tuscan dialect for works such as The New Life (1295) and the aforementioned Divine Comedy; this choice, though highly unorthodox, set a hugely important precedent that later Italian writers such as Petrarch and Boccaccio would follow. As a result, Dante played an instrumental role in establishing the national language of Italy. Dante’s significance also extends past his home country; his depictions of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven have provided inspiration for a large body of Western art, and are cited as an influence on the works of John Milton, Geoffrey Chaucer, and Lord Alfred Tennyson, among many others.

Dante, like most Florentines of his day, was embroiled in the Guelph-Ghibelline conflict. He fought in the Battle of Campaldino (June 11, 1289) with the Florentine Guelphs against the Arezzo Ghibellines. After defeating the Ghibellines, the Guelphs divided into two factions: the White Guelphs—Dante’s party, led by Vieri dei Cerchi—and the Black Guelphs, led by Corso Donati. Although the split was along family lines at first, ideological differences arose based on opposing views of the papal role in Florentine affairs, with the Blacks supporting the pope and the Whites wanting more freedom from Rome. Dante was accused of corruption and financial wrongdoing by the Black Guelphs for the time that he was serving as city prior (Florence’s highest position) for two months in 1300. He was condemned to perpetual exile; if he returned to Florence without paying a fine, he could be burned at the stake.

At some point during his exile he conceived of the Divine Comedy, but the date is uncertain. The work is much more assured and on a larger scale than anything he had produced in Florence; it is likely he would have undertaken such a work only after he realized his political ambitions, which had been central to him up to his banishment, had been halted for some time, possibly forever. Mixing religion and private concerns in his writings, he invoked the worst anger of God against his city and suggested several particular targets that were also his personal enemies.

Leonardo Bruni

Leonardo Bruni (c. 1370–March 9, 1444) was an Italian Humanist, historian, and statesman, often recognized as the most important Humanist historian of the early Renaissance. He has been called the first modern historian. He was the earliest person to write using the three-period view of history: Antiquity, Middle Ages, and Modern. The dates Bruni used to define the periods are not exactly what modern historians use today, but he laid the conceptual groundwork for a tripartite division of history.

Bruni’s most notable work is Historiarum Florentini populi libri XII (History of the Florentine People, 12 Books), which has been called the first modern history book. While it probably was not Bruni’s intention to secularize history, the three period view of history is unquestionably secular, and for that Bruni has been called the first modern historian. The foundation of Bruni’s conception can be found with Petrarch, who distinguished the classical period from later cultural decline, or tenebrae (literally “darkness”). Bruni argued that Italy had revived in recent centuries and could therefore be described as entering a new age.

One of Bruni’s most famous works is New Cicero, a biography of the Roman statesman Cicero. He was also the author of biographies in Italian of Dante and Petrarch. It was Bruni who used the phrase ” studia humanitatis,” meaning the study of human endeavors, as distinct from those of theology and metaphysics, which is where the term “humanists” comes from.

As a Humanist Bruni was essential in translating into Latin many works of Greek philosophy and history, such as those by Aristotle and Procopius. Bruni’s translations of Aristotle’s Politics and Nicomachean Ethics, as well as the pseudo-Aristotelean Economics, were widely distributed in manuscript and in print.

Christine de Pizan

Christine de Pizan was an Italian-French late medieval author who wrote about the positive contributions of women to European history and court life.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Discuss the significance of Christine de Pizan’s work

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- Christine de Pizan was an Italian-French late medieval author, primarily a court writer, who wrote commissioned works for aristocratic families and addressed literary debates of the era.

- Her work is characterized by a prominent and positive depiction of women who encouraged ethical and judicious conduct in courtly life.

- Much of the impetus for her writing came from her need to earn a living to support her mother, a niece, and her two surviving children after being widowed at the age of 25.

- Christine’s participation in a literary debate about Jean de Meun’s Romance of the Rose allowed her to move beyond the courtly circles, and ultimately to establish her status as a writer concerned with the position of women in society.

Key Terms

- feminism: A range of political movements, ideologies, and social movements that share a common goal: to define, establish, and achieve political, economic, personal, and social rights for women that are equal to those of men.

- chivalry: A code of conduct associated with the medieval institution of knighthood, which later developed into social and moral virtues more generally.

- alchemist: A person who practices the philosophical and proto-scientific tradition aimed to purify, mature, and perfect certain objects, such as the transmutation of “base metals” (e.g., lead) into “noble” ones (particularly gold) and the creation of an elixir of immortality.

Overview

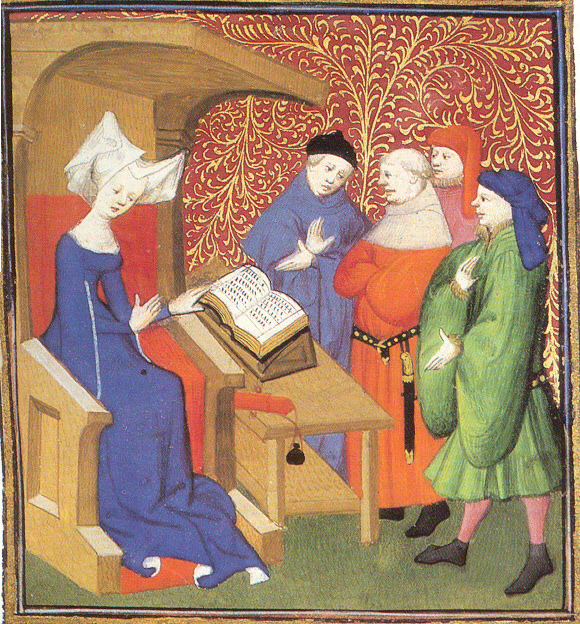

Christine de Pizan (1364–1430) was an Italian-French late medieval author. She served as a court writer for several dukes (Louis of Orleans, Philip the Bold of Burgundy, and John the Fearless of Burgundy) and the French royal court during the reign of Charles VI. She wrote both poetry and prose works such as biographies and books containing practical advice for women. She completed forty-one works during her thirty-year career from 1399 to 1429. She married in 1380 at the age of fifteen, and was widowed ten years later. Much of the impetus for her writing came from her need to earn a living to support her mother, a niece, and her two surviving children. She spent most of her childhood and all of her adult life in Paris and then the abbey at Poissy, and wrote entirely in her adopted language, Middle French.

In recent decades, Christine de Pizan’s work has been returned to prominence by the efforts of scholars such as Charity Cannon Willard, Earl Jeffrey Richards, and Simone de Beauvoir. Certain scholars have argued that she should be seen as an early feminist who efficiently used language to convey that women could play an important role within society.

Life

Christine de Pizan was born in 1364 in Venice, Italy. Following her birth, her father, Thomas de Pizan, accepted an appointment to the court of Charles V of France, as the king’s astrologer, alchemist, and physician. In this atmosphere, Christine was able to pursue her intellectual interests. She successfully educated herself by immersing herself in languages, in the rediscovered classics and Humanism of the early Renaissance, and in Charles V’s royal archive, which housed a vast number of manuscripts. But she did not assert her intellectual abilities, or establish her authority as a writer, until she was widowed at the age of 25.

In order to support herself and her family, Christine turned to writing. By 1393, she was writing love ballads, which caught the attention of wealthy patrons within the court. These patrons were intrigued by the novelty of a female writer and had her compose texts about their romantic exploits. Her output during this period was prolific. Between 1393 and 1412 she composed over 300 ballads, and many more shorter poems.

Christine’s participation in a literary debate, in 1401–1402, allowed her to move beyond the courtly circles, and ultimately to establish her status as a writer concerned with the position of women in society. During these years, she involved herself in a renowned literary controversy, the “Querelle du Roman de la Rose.” She helped to instigate this debate by beginning to question the literary merits of Jean de Meun’s The The Romance of the Rose. Written in the 13th century, The Romance of the Rose satirizes the conventions of courtly love while critically depicting women as nothing more than seducers. Christine specifically objected to the use of vulgar terms in Jean de Meun’s allegorical poem. She argued that these terms denigrated the proper and natural function of sexuality, and that such language was inappropriate for female characters such as Madam Reason. According to her, noble women did not use such language. Her critique primarily stemmed from her belief that Jean de Meun was purposely slandering women through the debated text.

The debate itself was extensive, and at its end the principal issue was no longer Jean de Meun’s literary capabilities; it had shifted to the unjust slander of women within literary texts. This dispute helped to establish Christine’s reputation as a female intellectual who could assert herself effectively and defend her claims in the male-dominated literary realm. She continued to counter abusive literary treatments of women.

Writing

Christine produced a large amount of vernacular works in both prose and verse. Her works include political treatises, mirrors for princes, epistles, and poetry.

Her early courtly poetry is marked by her knowledge of aristocratic custom and fashion of the day, particularly involving women and the practice of chivalry. Her early and later allegorical and didactic treatises reflect both autobiographical information about her life and views and also her own individualized and Humanist approach to the scholastic learned tradition of mythology, legend, and history she inherited from clerical scholars, and to the genres and courtly or scholastic subjects of contemporary French and Italian poets she admired. Supported and encouraged by important royal French and English patrons, she influenced 15th century English poetry.

By 1405, Christine had completed her most famous literary works, The Book of the City of Ladies and The Treasure of the City of Ladies. The first of these shows the importance of women’s past contributions to society, and the second strives to teach women of all estates how to cultivate useful qualities. In The Treasure of the City of Ladies, she highlights the persuasive effect of women’s speech and actions in everyday life. In this particular text, Christine argues that women must recognize and promote their ability to make peace between people. This ability will allow women to mediate between husband and subjects. She also argues that slanderous speech erodes one’s honor and threatens the sisterly bond among women. Christine then argues that “skill in discourse should be a part of every woman’s moral repertoire.” She believed that a woman’s influence is realized when her speech accords value to chastity, virtue, and restraint. She argued that rhetoric is a powerful tool that women could employ to settle differences and to assert themselves. Additionally, The Treasure of the City of Ladies provides glimpses into women’s lives in 1400, from the great lady in the castle down to the merchant’s wife, the servant, and the peasant. She offers advice to governesses, widows, and even prostitutes.

Machiavelli

Renaissance philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli sought to describe political life as it really was rather than its philosophical ideal, as infamously portrayed in his text The Prince.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Analyze Machiavelli’s impact during his own lifetime and in the modern day

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- Niccolò Machiavelli was an Italian Renaissance historian, politician, diplomat, philosopher, Humanist, and writer, often called the founder of modern political science.

- His writings were innovative because of his emphasis on practical and pragmatic strategies over philosophical ideals, exemplified by such phrases as “He who neglects what is done for what ought to be done, sooner effects his ruin than his preservation.”

- His most famous text, The Prince, has been profoundly influential, from the time of his life up to the present day, both on politicians and philosophers.

- The Prince describes strategies to be an effective statesman and infamously includes justifications for treachery and violence to retain power.

Key Terms

- republicanism: An ideology of being a citizen in a state in which power resides in elected individuals representing the citizen body.

- realpolitik: Politics or diplomacy based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than explicit ideological notions or moral and ethical premises.

- Machiavellian: Cunning and scheming in statecraft or in general conduct.

Overview

Niccolò Machiavelli (May 3, 1469–June 21, 1527) was an Italian Renaissance historian, politician, diplomat, philosopher, Humanist, and writer. He has often been called the founder of modern political science. He was for many years a senior official in the Florentine Republic, with responsibilities in diplomatic and military affairs. He also wrote comedies, carnival songs, and poetry. His personal correspondence is renowned in the Italian language. He was secretary to the Second Chancery of the Republic of Florence from 1498 to 1512, when the Medici were out of power. He wrote his most renowned work, The Prince (Il Principe) in 1513.

“Machiavellianism” is a widely used negative term to characterize unscrupulous politicians of the sort Machiavelli described most famously in The Prince. Machiavelli described immoral behavior, such as dishonesty and killing innocents, as being normal and effective in politics. He even seemed to endorse it in some situations. The book itself gained notoriety when some readers claimed that the author was teaching evil, and providing “evil recommendations to tyrants to help them maintain their power.” The term ” Machiavellian ” is often associated with political deceit, deviousness, and realpolitik. On the other hand, many commentators, such as Baruch Spinoza, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Denis Diderot, have argued that Machiavelli was actually a republican, even when writing The Prince, and his writings were an inspiration to Enlightenment proponents of modern democratic political philosophy.

The Prince

Machiavelli’s best-known book, The Prince, contains several maxims concerning politics. Instead of the more traditional target audience of a hereditary prince, it concentrates on the possibility of a “new prince.” To retain power, the hereditary prince must carefully balance the interests of a variety of institutions to which the people are accustomed. By contrast, a new prince has the more difficult task in ruling: he must first stabilize his newfound power in order to build an enduring political structure. Machiavelli suggests that the social benefits of stability and security can be achieved in the face of moral corruption. Machiavelli believed that a leader had to understand public and private morality as two different things in order to rule well. As a result, a ruler must be concerned not only with reputation, but also must be positively willing to act immorally at the right times.

As a political theorist, Machiavelli emphasized the occasional need for the methodical exercise of brute force or deceit, including extermination of entire noble families to head off any chance of a challenge to the prince’s authority. He asserted that violence may be necessary for the successful stabilization of power and introduction of new legal institutions. Further, he believed that force may be used to eliminate political rivals, to coerce resistant populations, and to purge the community of other men of strong enough character to rule, who will inevitably attempt to replace the ruler. Machiavelli has become infamous for such political advice, ensuring that he would be remembered in history through the adjective “Machiavellian.”

The Prince is sometimes claimed to be one of the first works of modern philosophy, especially modern political philosophy, in which the effective truth is taken to be more important than any abstract ideal. It was also in direct conflict with the dominant Catholic and scholastic doctrines of the time concerning politics and ethics. In contrast to Plato and Aristotle, Machiavelli insisted that an imaginary ideal society is not a model by which a prince should orient himself.

Influence

Machiavelli’s ideas had a profound impact on political leaders throughout the modern west, helped by the new technology of the printing press. During the first generations after Machiavelli, his main influence was in non-Republican governments. One historian noted that The Prince was spoken of highly by Thomas Cromwell in England and had influenced Henry VIII in his turn towards Protestantism and in his tactics, for example during the Pilgrimage of Grace. A copy was also possessed by the Catholic king and emperor Charles V. In France, after an initially mixed reaction, Machiavelli came to be associated with Catherine de’ Medici and the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre. As one historian reports, in the 16th century, Catholic writers “associated Machiavelli with the Protestants, whereas Protestant authors saw him as Italian and Catholic.” In fact, he was apparently influencing both Catholic and Protestant kings.

Modern materialist philosophy developed in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, starting in the generations after Machiavelli. This philosophy tended to be republican, more in the original spirit of Machiavellianism, but as with the Catholic authors, Machiavelli’s realism and encouragement of using innovation to try to control one’s own fortune were more accepted than his emphasis upon war and politics. Not only were innovative economics and politics results, but also modern science, leading some commentators to say that the 18th century Enlightenment involved a “humanitarian” moderating of Machiavellianism.

Although Jean-Jacques Rousseau is associated with very different political ideas, it is important to view Machiavelli’s work from different points of view rather than just the traditional notion. For example, Rousseau viewed Machiavelli’s work as a satirical piece in which Machiavelli exposes the faults of one-man rule rather than exalting amorality.

Scholars have argued that Machiavelli was a major indirect and direct influence upon the political thinking of the Founding Fathers of the United States due to his overwhelming favoritism of republicanism and the republic type of government. Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson followed Machiavelli’s republicanism when they opposed what they saw as the emerging aristocracy that they feared Alexander Hamilton was creating with the Federalist Party. Hamilton learned from Machiavelli about the importance of foreign policy for domestic policy, but may have broken from him regarding how rapacious a republic needed to be in order to survive.

Licenses and Attributions

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike