6.1: The Indus River Valley Civilizations

- Page ID

- 46105

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

The Indus River Valley Civilization

The Indus River Valley Civilization, located in modern Pakistan, was one of the world’s three earliest widespread societies.

Learning Objectives

Identify the importance of the discovery of the Indus River Valley Civilization

Key Takeaways

Key Points

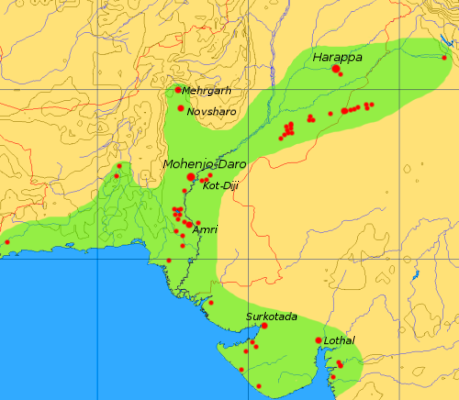

- The Indus Valley Civilization (also known as the Harappan Civilization) was a Bronze Age society extending from modern northeast Afghanistan to Pakistan and northwest India.

- The civilization developed in three phases: Early Harappan Phase (3300 BCE-2600 BCE), Mature Harappan Phase (2600 BCE-1900 BCE), and Late Harappan Phase (1900 BCE-1300 BCE).

- Inhabitants of the ancient Indus River valley developed new techniques in handicraft, including Carnelian products and seal carving, and metallurgy with copper, bronze, lead, and tin.

- Sir John Hubert Marshall led an excavation campaign in 1921-1922, during which he discovered the ruins of the city of Harappa. By 1931, the Mohenjo-daro site had been mostly excavated by Marshall and Sir Mortimer Wheeler. By 1999, over 1,056 cities and settlements of the Indus Civilization were located.

Key Terms

- seal: An emblem used as a means of authentication. Seal can refer to an impression in paper, wax, clay, or other medium. It can also refer to the device used.

- metallurgy: The scientific and mechanical technique of working with bronze. copper, and tin.

The Indus Valley Civilization existed through its early years of 3300-1300 BCE, and its mature period of 2600-1900 BCE. The area of this civilization extended along the Indus River from what today is northeast Afghanistan, into Pakistan and northwest India. The Indus Civilization was the most widespread of the three early civilizations of the ancient world, along with Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Harappa and Mohenjo-daro were thought to be the two great cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, emerging around 2600 BCE along the Indus River Valley in the Sindh and Punjab provinces of Pakistan. Their discovery and excavation in the 19th and 20th centuries provided important archaeological data about ancient cultures.

Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization was one of the three “Ancient East” societies that are considered to be the cradles of civilization of the old world of man, and are among the most widespread; the other two “Ancient East” societies are Mesopotamia and Pharonic Egypt. The lifespan of the Indus Valley Civilization is often separated into three phases: Early Harappan Phase (3300-2600 BCE), Mature Harappan Phase (2600-1900 BCE) and Late Harappan Phase (1900-1300 BCE).

At its peak, the Indus Valley Civilization may had a population of over five million people. It is considered a Bronze Age society, and inhabitants of the ancient Indus River Valley developed new techniques in metallurgy—the science of working with copper, bronze, lead, and tin. They also performed intricate handicraft, especially using products made of the semi-precious gemstone Carnelian, as well as seal carving— the cutting

of patterns into the bottom face of a seal used for stamping. The Indus cities are noted for their urban planning, baked brick houses, elaborate drainage systems, water supply systems, and clusters of large, non-residential buildings.

The Indus Valley Civilization is also known as the Harappan Civilization, after Harappa, the first of its sites to be excavated in the 1920s, in what was then the Punjab province of British India and is now in Pakistan. The discoveries of Harappa, and the site of its fellow Indus city Mohenjo-daro, were the culmination of work beginning in 1861 with the founding of the Archaeological Survey of India in the British Raj, the common name for British imperial rule over the Indian subcontinent from 1858 through 1947.

Harappa and Mohenjo-daro

Harappa was a fortified city in modern-day Pakistan that is believed to have been home to as many as 23,500 residents living in sculpted houses with flat roofs made of red sand and clay. The city spread over 150 hectares (370 acres) and had fortified administrative and religious centers of the same type used in Mohenjo-daro. The modern village of Harappa, used as a railway station during the Raj, is six kilometers (3.7 miles) from the ancient city site, which suffered heavy damage during the British period of rule.

Mohenjo-daro is thought to have been built in the 26th century BCE and became not only the largest city of the Indus Valley Civilization but one of the world’s earliest, major urban centers. Located west of the Indus River in the Larkana District, Mohenjo-daro was one of the most sophisticated cities of the period, with sophisticated engineering and urban planning. Cock-fighting was thought to have religious and ritual significance, with domesticated chickens bred for religion rather than food (although the city may have been a point of origin for the worldwide domestication of chickens). Mohenjo-daro was abandoned around 1900 BCE when the Indus Civilization went into sudden decline.

The ruins of Harappa were first described in 1842 by Charles Masson in his book, Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan, the Panjab, & Kalât. In 1856, British engineers John and William Brunton were laying the East Indian Railway Company line connecting the cities of Karachi and Lahore, when their crew discovered hard, well-burnt bricks in the area and used them for ballast for the railroad track, unwittingly dismantling the ruins of the ancient city of Brahminabad.

Excavations

In 1912, John Faithfull Fleet, an English civil servant working with the Indian Civil Services, discovered several Harappan seals. This prompted an excavation campaign from 1921-1922 by Sir John Hubert Marshall, Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India, which resulted in the discovery of Harappa. By 1931, much of

Mohenjo-Daro had been excavated, while the next director of the Archaeological Survey of India, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, led additional excavations.

The Partition of India, in 1947, divided the country to create the new nation of Pakistan. The bulk of the archaeological finds that followed were inherited by Pakistan. By 1999, over 1,056 cities and settlements had been found, of which 96 have been excavated.

Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus River Valley Civilization (IVC) contained urban centers with well-conceived and organized infrastructure, architecture, and systems of governance.

Learning Objectives

Explain the significance of the urban centers in the IVC

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Indus Valley Civilization contained more than 1,000 cities and settlements.

- These cities contained well-organized wastewater drainage systems, trash collection systems, and possibly even public granaries and baths.

- Although there were large walls and citadels, there is no evidence of monuments, palaces, or temples.

- The uniformity of Harappan artifacts suggests some form of authority and governance to regulate seals, weights, and bricks.

Key Terms

- granaries: A storehouse or room in a barn for threshed grain or animal feed.

- citadels: A central area in a city that is heavily fortified.

- Harappa and Mohenjo-daro: Two of the major cities of the Indus Valley Civilization during the Bronze Age.

- urban planning: A technical and political process concerned with the use of land and design of the urban environment that guides and ensures the orderly development of settlements and communities.

By 2600 BCE, the small Early Harappan communities had become large urban centers. These cities include Harappa, Ganeriwala, and Mohenjo-daro in modern-day Pakistan, and Dholavira, Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Rupar, and Lothal in modern-day India. In total, more than 1,052 cities and settlements have been found, mainly in the general region of the Indus River and its tributaries. The population of the Indus Valley Civilization may have once been as large as five million.

The remains of the Indus Valley Civilization cities indicate remarkable organization; there were well-ordered wastewater drainage and trash collection systems, and possibly even public granaries and baths. Most city-dwellers were artisans and merchants grouped together in distinct neighborhoods. The quality of urban planning suggests efficient municipal governments that placed a high priority on hygiene or religious ritual.

Infrastructure

Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and the recently, partially-excavated Rakhigarhi demonstrate the world’s first known urban sanitation systems. The ancient Indus systems of sewerage and drainage developed and used in cities throughout the Indus region were far more advanced than any found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle East, and even more efficient than those in many areas of Pakistan and India today. Individual homes drew water from wells, while waste water was directed to covered drains on the main streets. Houses opened only to inner courtyards and smaller lanes, and even the smallest homes on the city outskirts were believed to have been connected to the system, further supporting the conclusion that cleanliness was a matter of great importance.

Architecture

Harappans demonstrated advanced architecture with dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick platforms, and protective walls. These massive walls likely protected the Harappans from floods and may have dissuaded military conflicts. Unlike Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, the inhabitants of the Indus Valley Civilization did not build large, monumental structures. There is no conclusive evidence of palaces or temples (or even of kings, armies, or priests), and the largest structures may be granaries. The city of Mohenjo-daro contains the “Great Bath,” which may have been a large, public bathing and social area.

Authority and Governance

Archaeological records provide no immediate answers regarding a center of authority, or depictions of people in power in Harappan society. The extraordinary uniformity of Harappan artifacts is evident in pottery, seals, weights, and bricks with standardized sizes and weights, suggesting some form of authority and governance.

Over time, three major theories have developed concerning Harappan governance or system of rule. The first is that there was a single state encompassing all the communities of the civilization, given the similarity in artifacts, the evidence of planned settlements, the standardized ratio of brick size, and the apparent establishment of settlements near sources of raw material. The second theory posits that there was no single ruler, but a number of them representing each of the urban centers, including Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, and other communities. Finally, experts have theorized that the Indus Valley Civilization had no rulers as we understand them, with everyone enjoying equal status.

Harappan Culture

The Indus River Valley Civilization, also known as Harappan, included its own advanced technology, economy, and culture.

Learning Objectives

Identify how artifacts and ruins provided insight into the IRV’s technology, economy, and culture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Indus River Valley Civilization, also known as Harappan civilization, developed the first accurate system of standardized weights and measures, some as accurate as to 1.6 mm.

- Harappans created sculpture, seals, pottery, and jewelry from materials, such as terracotta, metal, and stone.

- Evidence shows Harappans participated in a vast maritime trade network extending from Central Asia to modern-day Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, and Syria.

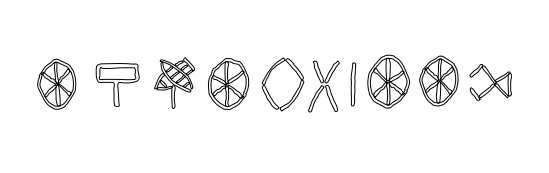

- The Indus Script remains indecipherable without any comparable symbols, and is thought to have evolved independently of the writing in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.

Key Terms

- steatite: Also known as Soapstone, steatite is a talc-schist, which is a type of metamorphic rock. It is very soft and has been a medium for carving for thousands of years.

- Indus Script: Symbols produced by the ancient Indus Valley Civilization.

- chalcolithic period: A period also

known as the Copper Age, which lasted from 4300-3200 BCE.

The Indus Valley Civilization is the earliest known culture of the Indian subcontinent of the kind now called “urban” (or centered on large municipalities), and the largest of the four ancient civilizations, which also included Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China. The society of the Indus River Valley has been dated from the Bronze Age, the time period from approximately 3300-1300 BCE. It was located in modern-day India and Pakistan, and covered an area as large as Western Europe.

Harappa and Mohenjo-daro were the two great cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, emerging around 2600 BCE along the Indus River Valley in the Sindh and Punjab provinces of Pakistan. Their discovery and excavation in the 19th and 20th centuries provided important archaeological data regarding the civilization’s technology, art, trade, transportation, writing, and religion.

Technology

The people of the Indus Valley, also known as Harappan (Harappa was the first city in the region found by archaeologists), achieved many notable advances in technology, including great accuracy in their systems and tools for measuring length and mass.

Harappans were among the first to develop a system of uniform weights and measures that conformed to a successive scale. The smallest division, approximately 1.6 mm, was marked on an ivory scale found in Lothal, a prominent Indus Valley city in the modern Indian state of Gujarat. It stands as the smallest division ever recorded on a Bronze Age scale. Another indication of an advanced measurement system is the fact that the bricks used to build Indus cities were uniform in size.

Harappans demonstrated advanced architecture with dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick platforms, and protective walls. The ancient Indus systems of sewerage and drainage developed and used in cities throughout the region were far more advanced than any found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle East, and even more efficient than those in many areas of Pakistan and India today.

Harappans were thought to have been proficient in seal carving, the cutting of patterns into the bottom face of a seal, and used distinctive seals for the identification of property and to stamp clay on trade goods. Seals have been one of the most commonly discovered artifacts in Indus Valley cities, decorated with animal figures, such as elephants, tigers, and water buffalos.

Harappans also developed new techniques in metallurgy—the science of working with copper, bronze, lead, and tin—and performed intricate handicraft using products made of the semi-precious gemstone, Carnelian.

Art

Indus Valley excavation sites have revealed a number of distinct examples of the culture’s art, including sculptures, seals, pottery, gold jewelry, and anatomically detailed figurines in terracotta, bronze, and steatite—more commonly known as Soapstone.

Among the various gold, terracotta, and stone figurines found, a figure of a “Priest-King” displayed a beard and patterned robe. Another figurine in bronze, known as the “Dancing Girl,” is only 11 cm. high and shows a female figure in a pose that suggests the presence of some choreographed dance form enjoyed by members of the civilization. Terracotta works also included cows, bears, monkeys, and dogs. In addition to figurines, the Indus River Valley people are believed to have created necklaces, bangles, and other ornaments.

Trade and Transportation

The civilization’s economy appears to have depended significantly on trade, which was facilitated by major advances in transport technology. The Harappan Civilization may have been the first to use wheeled transport, in the form of bullock carts that are identical to those seen throughout South Asia today. It also appears they built boats and watercraft—a claim supported by archaeological discoveries of a massive, dredged canal, and what is regarded as a docking facility at the coastal city of Lothal.

Trade focused on importing raw materials to be used in Harappan city workshops, including minerals from Iran and Afghanistan, lead and copper from other parts of India, jade from China, and cedar wood floated down rivers from the Himalayas and Kashmir. Other trade goods included terracotta pots, gold, silver, metals, beads, flints for making tools, seashells, pearls, and colored gem stones, such as lapis lazuli and turquoise.

There was an extensive maritime trade network operating between the Harappan and Mesopotamian civilizations. Harappan seals and jewelry have been found at archaeological sites in regions of Mesopotamia, which includes most of modern-day Iraq, Kuwait, and parts of Syria. Long-distance sea trade over bodies of water, such as the Arabian Sea, Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, may have become feasible with the development of plank watercraft that was equipped with a single central mast supporting a sail of woven rushes or cloth.

During 4300-3200 BCE of the Chalcolithic period, also known as the Copper Age, the Indus Valley Civilization area shows ceramic similarities with

southern Turkmenistan and northern Iran. During the Early Harappan period (about 3200-2600 BCE), cultural similarities in pottery, seals, figurines, and ornaments document caravan trade with Central Asia and the Iranian plateau.

Writing

Harappans are believed to have used Indus Script, a language consisting of symbols. A collection of written texts on clay and stone tablets unearthed at Harappa, which have been carbon dated 3300-3200 BCE, contain trident-shaped, plant-like markings. This Indus Script suggests that writing developed independently in the Indus River Valley Civilization from the script employed in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.

As many as 600 distinct Indus symbols have been found on seals, small tablets, ceramic pots, and more than a dozen other materials. Typical Indus inscriptions are no more than four or five characters in length, most of which are very small. The longest on a single surface, which is less than 1 inch (or 2.54 cm.) square, is 17 signs long. The characters are largely pictorial, but include many abstract signs that do not appear to have changed over time.

The inscriptions are thought to have been primarily written from right to left, but it is unclear whether this script constitutes a complete language. Without a “Rosetta Stone” to use as a comparison with other writing systems, the symbols have remained indecipherable to linguists and archaeologists.

A Rosetta Stone for the Indus script, lecture by Rajesh Rao: Rajesh Rao is fascinated by “the mother of all crossword puzzles,” how to decipher the 4,000-year-old Indus script. At TED 2011, he explained how he was enlisting modern computational techniques to read the Indus language. View full lesson: http://ed.ted.com/lessons/a-rosetta-...ipt-rajesh-rao

Religion

The Harappan religion remains a topic of speculation. It has been widely suggested that the Harappans worshipped a mother goddess who symbolized fertility. In contrast to Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, the Indus Valley Civilization seems to have lacked any temples or palaces that would give clear evidence of religious rites or specific deities. Some Indus Valley seals show a swastika symbol, which was included in later Indian religions including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

Many Indus Valley seals also include the forms of animals, with some depicting them being carried in processions, while others showing chimeric creations, leading scholars to speculate about the role of animals in Indus Valley religions. One seal from Mohenjo-daro shows a half-human, half-buffalo monster attacking a tiger. This may be a reference to the Sumerian myth of a monster created by Aruru, the Sumerian earth and fertility goddess, to fight Gilgamesh, the hero of an ancient Mesopotamian epic poem. This is a further suggestion of international trade in Harappan culture.

Disappearance of the Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization declined around 1800 BCE due to climate

change and migration.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the causes for the disappearance of the Indus Valley Civilization

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- One theory suggested that a nomadic, Indo-European tribe, called the Aryans, invaded and conquered the Indus Valley Civilization.

- Many scholars now believe the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization was caused by climate change.

- The eastward shift of monsoons may have reduced the water supply, forcing the Harappans of the Indus River Valley to migrate and establish smaller villages and isolated farms.

- These small communities could not produce the agricultural surpluses needed to support cities, which where then abandoned.

Key Terms

- Indo-Aryan Migration theory: A theory suggesting the Harappan culture of the Indus River Valley was assimilated during a migration of the Aryan people into northwest India.

- monsoon: Seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation; usually winds that bring heavy rain once a year.

- Aryans: A nomadic, Indo-European tribe called the Aryans suddenly overwhelmed and conquered the Indus Valley Civilization.

The great Indus Valley Civilization, located in modern-day India and Pakistan, began to decline around 1800 BCE. The civilization eventually disappeared along with its two great cities, Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. Harappa lends its name to the Indus Valley people because it was the civilization’s first city to be discovered by modern archaeologists.

Archaeological evidence indicates that trade with Mesopotamia, located largely in modern Iraq, seemed to have ended. The advanced drainage system and baths of the great cities were built over or blocked. Writing began to disappear and the standardized weights and measures used for trade and taxation fell out of use.

Scholars have put forth differing theories to explain the disappearance of the Harappans, including an Aryan Invasion and climate change marked by overwhelming monsoons.

The Aryan Invasion Theory (c. 1800-1500 BC)

The Indus Valley Civilization may have met its demise due to invasion. According to one theory by British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler, a nomadic, Indo-European tribe, called the Aryans, suddenly overwhelmed and conquered the Indus River Valley.

Wheeler, who was Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India from 1944 to 1948, posited that many unburied corpses found in the top levels of the Mohenjo-daro archaeological site were victims of war. The theory suggested that by using horses and more advanced weapons against the peaceful Harappan people, the Aryans may have easily defeated them.

Yet shortly after Wheeler proposed his theory, other scholars dismissed it by explaining that the skeletons were not victims of invasion massacres, but rather the remains of hasty burials. Wheeler himself eventually admitted that the theory could not be proven and the skeletons indicated only a final phase of human occupation, with the decay of the city structures likely a result of it becoming uninhabited.

Later opponents of the invasion theory went so far as to state that adherents to the idea put forth in the 1940s were subtly justifying the British government’s policy of intrusion into, and subsequent colonial rule over, India.

Various elements of the Indus Civilization are found in later cultures, suggesting the civilization did not disappear suddenly due to an invasion. Many scholars came to believe in an Indo-Aryan Migration theory stating that the Harappan culture was assimilated during a migration of the Aryan people into northwest India.

The Climate

Change Theory (c. 1800-1500 BC)

Other scholarship suggests the collapse of Harappan society resulted from climate change. Some experts believe the drying of the Saraswati River, which began around 1900 BCE, was the main cause for climate change, while others conclude that a great flood struck the area.

Any major environmental change, such as deforestation, flooding or droughts due to a river changing course, could have had disastrous effects on Harappan society, such as crop failures, starvation, and disease. Skeletal evidence suggests many people died from malaria, which is most often spread by mosquitoes. This also would have caused a breakdown in the economy and civic order within the urban areas.

Another disastrous change in the Harappan climate might have been eastward-moving monsoons, or winds that bring heavy rains. Monsoons can be both helpful and detrimental to a climate, depending on whether they support or destroy vegetation and agriculture. The monsoons that came to the Indus River Valley aided the growth of agricultural surpluses, which supported the development of cities, such as Harappa. The population came to rely on seasonal monsoons rather than irrigation, and as the monsoons shifted eastward, the water supply would have dried up.

By 1800 BCE, the Indus Valley climate grew cooler and drier, and a tectonic event may have diverted the Ghaggar Hakra river system toward the Ganges Plain. The Harappans may have migrated toward the Ganges basin in the east, where they established villages and isolated farms.

These small communities could not produce the same agricultural surpluses to support large cities. With the reduced production of goods, there was a decline in trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia. By around 1700 BCE, most of the Indus Valley Civilization cities had been abandoned.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sir Mortimer Wheeler. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mortimer_Wheeler. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Indus River Valley Civilizations (ca. 2800 - 1800 BC). Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/World_History/Civilization_and_Empires_in_the_Indian_Subcontinent. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Harappa. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pakistan. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pakistan. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Metallurgy. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metallurgy. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bronze Age. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bronze_Age. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sir John Hubert Marshall. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Marshall_(archaeologist). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mohenjo-dara. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo-daro. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Indus Valley Civilization. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilisation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Indus Valley Civilization. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:IVC-major-sites-2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Mohenjodaro Sindh. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mohenjodaro_Sindh.jpeg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Indus River Valley Civilization. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilization. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Indus River Valley Civilizations. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/World_History/Civilization_and_Empires_in_the_Indian_Subcontinent. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Harappa. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mohenjo-daro. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo-daro. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Indus Valley Civilization. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:IVC-major-sites-2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Mohenjodaro Sindh. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mohenjodaro_Sindh.jpeg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- IVC Map. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:IVC_Map.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Sokhta Koh. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sokhta_Koh.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Indus Script. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_script. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Indus Valley Civilisation. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilisation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Harappa. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Indus River Valley Civilization. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/World_History/Civilization_and_Empires_in_the_Indian_Subcontinent. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Rosetta Stone. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosetta_Stone. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Indus Valley Civilization. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:IVC-major-sites-2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Mohenjodaro Sindh. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mohenjodaro_Sindh.jpeg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- IVC Map. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:IVC_Map.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Sokhta Koh. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sokhta_Koh.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- A Rosetta Stone for the Indus script, lecture by Rajesh Rao. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a_-obTZO6pY. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Shiva Pashupati. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shiva_Pashupati.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The'Ten Indus Scripts' discovered near the northen gateway of the citadel Dholavira.svg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The%27Ten_Indus_Scripts%27_discovered_near_the_northen_gateway_of_the_citadel_Dholavira.svg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Harappan small figures. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harappan_small_figures.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- dock with canal in Lothal (India). Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lothal_dock.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Indo-Aryan Migration Theory. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Aryan_migration_theory. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mortimer Wheeler. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mortimer_Wheeler. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aryan Race. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aryan_race. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Monsoon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monsoon. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Civilizations and Empires in the Indian Subcontinent. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/World_History/Civilization_and_Empires_in_the_Indian_Subcontinent. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Indus Valley Civilisation Collapse. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilisation#Collapse_and_Late_Harappan. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Indus Valley Civilisation. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilisation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Indus Valley Civilization. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:IVC-major-sites-2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Mohenjodaro Sindh. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mohenjodaro_Sindh.jpeg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- IVC Map. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:IVC_Map.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Sokhta Koh. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sokhta_Koh.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- A Rosetta Stone for the Indus script, lecture by Rajesh Rao. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a_-obTZO6pY. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Shiva Pashupati. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shiva_Pashupati.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The'Ten Indus Scripts' discovered near the northen gateway of the citadel Dholavira.svg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The%27Ten_Indus_Scripts%27_discovered_near_the_northen_gateway_of_the_citadel_Dholavira.svg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Harappan small figures. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harappan_small_figures.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- dock with canal in Lothal (India). Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lothal_dock.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Aryans Settling in India. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aryans_settling_in_India.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Lothal - bathroom structure. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lothal_-_bathroom_structure.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright