4.5: Ancient Egyptian Society

- Page ID

- 46098

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Ancient Egyptian Religion

Ancient Egyptian religion lasted for more than 3,000 years, and consisted of a complex polytheism. The pharaoh’s role was to sustain the gods in order to maintain order in the universe.

Learning Objectives

Describe the religious beliefs and practices of Ancient Egypt

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The religion of Ancient Egypt lasted for more than 3,000 years, and was polytheistic, meaning there were a multitude of deities, who were believed to reside within and control the forces of nature.

- Formal religious practice centered on the pharaoh, or ruler, of Egypt, who was believed to be divine, and acted as intermediary between the people and the gods. His role was to sustain the gods so that they could maintain order in the universe.

- The Egyptian universe centered on Ma’at, which has several meanings in English, including truth, justice and order. It was fixed and eternal; without it the world would fall apart.

- The most important myth was of Osiris and Isis. The divine ruler Osiris was murdered by Set (god of chaos ), then resurrected by his sister and wife Isis to conceive an heir, Horus. Osiris then became the ruler of the dead, while Horus eventually avenged his father and became king.

- Egyptians were very concerned about the fate of their souls after death. They believed ka (life-force) left the body upon death and needed to be fed. Ba, or personal spirituality, remained in the body. The goal was to unite ka and ba to create akh.

- Artistic depictions of gods were not literal representations, as their true nature was considered mysterious. However, symbolic imagery was used to indicate this nature.

- Temples were the state’s method of sustaining the gods, since their physical images were housed and cared for; temples were not a place for the average person to worship.

- Certain animals were worshipped and mummified as representatives of gods.

- Oracles were used by all classes.

Key Terms

- polytheistic: A religion with more than one worshipped god.

- Duat: The realm of the dead; residence of Osiris.

- ka: The spiritual part of an individual human being or god that survived after death.

- pantheon: The core actors of a religion.

- heka: The ability to use natural forces to create “magic.”

- Ma’at,: The Egyptian universe.

- ba: The spiritual characteristics of an individual person that remained in the body after death. Ba could unite with the ka.

- akh: The combination of the ka and ba living in the afterlife.

The religion of Ancient Egypt lasted for more than 3,000 years, and was polytheistic, meaning there were a multitude of deities, who were believed to reside within and control the forces of nature. Religious practices were deeply embedded in the lives of Egyptians, as they attempted to provide for their gods and win their favor. The complexity of the religion was evident as some deities existed in different manifestations and had multiple mythological roles. The pantheon included gods with major roles in the universe, minor deities (or “demons”), foreign gods, and sometimes humans, including deceased Pharaohs.

Formal religious practice centered on the pharaoh, or ruler, of Egypt, who was believed to be divine, and acted as intermediary between the people and the gods. His role was to sustain the gods so that they could maintain order in the universe, and the state spent its resources generously to build temples and provide for rituals. The pharaoh was associated with Horus (and later Amun) and seen as the son of Ra. Upon death, the pharaoh was fully deified, directly identified with Ra and associated with Osiris, the god of death and rebirth. However, individuals could appeal directly to the gods for personal purposes through prayer or requests for magic; as the pharaoh’s power declined, this personal form of practice became stronger. Popular religious practice also involved ceremonies around birth and naming. The people also invoked “magic” (called heka) to make things happen using natural forces.

Cosmology

The Egyptian universe centered on Ma’at, which has several meanings in English, including truth, justice and order. It was fixed and eternal (without it the world would fall apart), and there were constant threats of disorder requiring society to work to maintain it. Inhabitants of the cosmos included the gods, the spirits of deceased humans, and living humans, the most important of which was the pharaoh. Humans should cooperate to achieve this, and gods should function in balance. Ma’at was renewed by periodic events, such as the annual Nile flood, which echoed the original creation. Most important of these was the daily journey of the sun god Ra.

Egyptians saw the earth as flat land (the god Geb), over which arched the sky (goddess Nut); they were separated by Shu, the god of air. Underneath the earth was a parallel underworld and undersky, and beyond the skies lay Nu, the chaos before creation. Duat was a mysterious area associated with death and rebirth, and each day Ra passed through Duat after traveling over the earth during the day.

Myths

Egyptian myths are mainly known from hymns, ritual and magical texts, funerary texts, and the writings of Greeks and Romans. The creation myth saw the world as emerging as a dry space in the primordial ocean of chaos, marked by the first rising of Ra. Other forms of the myth saw the primordial god Atum transforming into the elements of the world, and the creative speech of the intellectual god Ptah.

The most important myth was of Osiris and Isis. The divine ruler Osiris was murdered by Set (god of chaos), then resurrected by his sister and wife Isis to conceive an heir, Horus. Osiris then became the ruler of the dead, while Horus eventually avenged his father and became king. This myth set the Pharaohs, and their succession, as orderliness against chaos.

The Afterlife

Egyptians were very concerned about the fate of their souls after death, and built tombs, created grave goods and gave offerings to preserve the bodies and spirits of the dead. They believed humans possessed ka, or life-force, which left the body at death. To endure after death, the ka must continue to receive offerings of food; it could consume the spiritual essence of it. Humans also possessed a ba, a set of spiritual characteristics unique to each person, which remained in the body after death. Funeral rites were meant to release the ba so it could move, rejoin with the ka, and live on as an akh. However, the ba returned to the body at night, so the body must be preserved.

Mummification involved elaborate embalming practices, and wrapping in cloth, along with various rites, including the Opening of the Mouth ceremony. Tombs were originally mastabas (rectangular brick structures), and then pyramids.

However, this originally did not apply to the common person: they passed into a dark, bleak realm that was the opposite of life. Nobles did receive tombs and grave gifts from the pharaoh. Eventually, by about 2181 BCE, Egyptians began to believe every person had a ba and could access the afterlife. By the New Kingdom, the soul had to face dangers in the Duat before having a final judgment, called the Weighing of the Heart, where the gods compared the actions of the deceased while alive to Ma’at, to see if they were worthy. If so, the ka and ba were united into an akh, which then either traveled to the lush underworld, or traveled with Ra on his daily journey, or even returned to the world of the living to carry out magic.

Rise and Fall of Gods

Certain gods gained a primary status over time, and then fell as other gods overtook them. These included the sun god Ra, the creator god Amun, and the mother goddess Isis. There was even a period of time where Egypt was monotheistic, under Pharaoh Akhenaten, and his patron god Aten.

The Relationships of Deities

Just as the forces of nature had complex interrelationships, so did Egyptian deities. Minor deities might be linked, or deities might come together based on the meaning of numbers in Egyptian mythology (i.e., pairs represented duality). Deities might also be linked through syncretism, creating a composite deity.

Artistic Depictions of Gods

Artistic depictions of gods were not literal representations, since their true nature was considered mysterious. However, symbolic imagery was used to indicate this nature. An example was Anubis, a funerary god, who was shown as a jackal to counter its traditional meaning as a scavenger, and create protection for the mummy.

Temples

Temples were the state’s method of sustaining the gods, as their physical images were housed and cared for; they were not a place for the average person to worship. They were both mortuary temples to serve deceased pharaohs and temples for patron gods. Starting as simple structures, they grew more elaborate, and were increasingly built from stone, with a common plan. Ritual duties were normally carried out by priests, or government officials serving in the role. In the New Kingdom, professional priesthood became common, and their wealth rivaled that of the pharaoh.

Rituals and Festivals

Aside from numerous temple rituals, including the morning offering ceremony and re-enactments of myths, there were coronation ceremonies and the sed festival, a renewal of the pharaoh’s strength during his reign. The Opet Festival at Karnak involved a procession carrying the god’s image to visit other significant sites.

Animal Worship

At many sites, Egyptians worshipped specific animals that they believed to be manifestations of deities. Examples include the Apis bull (of the god Ptah), and mummified cats and other animals.

Use of Oracles

Commoners and pharaohs asked questions of oracles, and answers could even be used during the New Kingdom to settle legal disputes. This might involve asking a question while a divine image was being carried, and interpreting movement, or drawing lots.

Ancient Egyptian Art

Ancient Egyptian art included painting, sculpture, pottery, glass work, and architecture. Many surviving art is related to tombs and monuments. Aside from the brief Amarna period, Egyptian art remained relatively unchanged for thousands of years.

Learning Objectives

Examine the development of Egyptian Art under the Old Kingdom.

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Ancient Egyptian art includes painting, sculpture, architecture, and other forms of art, such as drawings on papyrus, created between 3000 BCE and 100 CE.

- Most of this art was highly stylized and symbolic. Much of the surviving forms come from tombs and monuments, and thus have a focus on life after death and preservation of knowledge.

- Symbolism meant order, shown through the pharaoh ‘s regalia, or through the use of certain colors.

- In Egyptian art, the size of a figure indicates its relative importance.

- Paintings were often done on stone, and portrayed pleasant scenes of the afterlife in tombs.

- Ancient Egyptians created both monumental and smaller sculptures, using the technique of sunk relief.

- Ka statues, which were meant to provide a resting place for the ka part of the soul, were often made of wood and placed in tombs.

- Faience was sintered-quartz ceramic with surface vitrification, used to create relatively cheap small objects in many colors. Glass was originally a luxury item but became more common, and was used to make small jars, for perfume and other liquids, to be placed in tombs. Carvings of vases, amulets, and images of deities and animals were made of steatite. Pottery was sometimes covered with enamel, particularly in the color blue.

- Papyrus was used for writing and painting, and and was used to record every aspect of Egyptian life.

- Architects carefully planned buildings, aligning them with astronomically significant events, such as solstices and equinoxes. They used mainly sun-baked mud brick, limestone, sandstone, and granite.

- The Amarna period (1353-1336 BCE) represents an interruption in ancient Egyptian art style, subjects were represented more realistically, and scenes included portrayals of affection among the royal family.

Key Terms

- papyrus: A material prepared in ancient Egypt from the stem of a water plant, used in sheets for writing or painting on.

- regalia: The emblems or insignia of royalty.

- sunk relief: Sculptural technique in which the outlines of modeled forms are incised in a plane surface beyond which the forms do not project.

- Ka: The supposed spiritual part of an individual human being or god that survived after death, and could reside in a statue of the person.

- ushabti: Ancient Egyptian funerary figure.

- Faience: Glazed ceramic ware.

- scarabs: Ancient Egyptian gem cut in the form of a scarab beetle

Ancient Egyptian art includes painting, sculpture, architecture, and other forms of art, such as drawings on papyrus, created between 3000 BCE and 100 AD. Most of this art was highly stylized and symbolic. Many of the surviving forms come from tombs and monuments, and thus have a focus on life after death and preservation of knowledge.

Symbolism

Symbolism in ancient Egyptian art conveyed a sense of order and the influence of natural elements. The regalia of the pharaoh symbolized his or her power to rule and maintain the order of the universe. Blue and gold indicated divinity because they were rare and were associated with precious materials, while black expressed the fertility of the Nile River.

Hierarchical Scale

In Egyptian art, the size of a figure indicates its relative importance. This meant gods or the pharaoh were usually bigger than other figures, followed by figures of high officials or the tomb owner; the smallest figures were servants, entertainers, animals, trees and architectural details.

Painting

Before painting a stone surface, it was whitewashed and sometimes covered with mud plaster. Pigments were made of mineral and able to stand up to strong sunlight with minimal fade. The binding medium is unknown; the paint was applied to dried plaster in the “fresco a secco” style. A varnish or resin was then applied as a protective coating, which, along with the dry climate of Egypt, protected the painting very well. The purpose of tomb paintings was to create a pleasant afterlife for the dead person, with themes such as journeying through the afterworld, or deities providing protection. The side view of the person or animal was generally shown, and paintings were often done in red, blue, green, gold, black and yellow.

Sculpture

Ancient Egyptians created both monumental and smaller sculptures, using the technique of sunk relief. In this technique, the image is made by cutting the relief sculpture into a flat surface, set within a sunken area shaped around the image. In strong sunlight, this technique is very visible, emphasizing the outlines and forms by shadow. Figures are shown with the torso facing front, the head in side view, and the legs parted, with males sometimes darker than females. Large statues of deities (other than the pharaoh) were not common, although deities were often shown in paintings and reliefs.

Colossal sculpture on the scale of the Great Sphinx of Giza was not repeated, but smaller sphinxes and animals were found in temple complexes. The most sacred cult image of a temple’s god was supposedly held in the naos in small boats, carved out of precious metal, but none have survived.

Ka statues, which were meant to provide a resting place for the ka part of the soul, were present in tombs as of Dynasty IV (2680-2565 BCE). These were often made of wood, and were called reserve heads, which were plain, hairless and naturalistic. Early tombs had small models of slaves, animals, buildings, and objects to provide life for the deceased in the afterworld. Later, ushabti figures were present as funerary figures to act as servants for the deceased, should he or she be called upon to do manual labor in the afterlife.

Many small carved objects have been discovered, from toys to utensils, and alabaster was used for the more expensive objects. In creating any statuary, strict conventions, accompanied by a rating system, were followed. This resulted in a rather timeless quality, as few changes were instituted over thousands of years.

Faience, Pottery, and Glass

Faience was sintered-quartz ceramic with surface vitrification used to create relatively cheap, small objects in many colors, but most commonly blue-green. It was often used for jewelry, scarabs, and figurines. Glass was originally a luxury item, but became more common, and was to used to make small jars, of perfume and other liquids, to be placed in tombs. Carvings of vases, amulets, and images of deities and animals were made of steatite. Pottery was sometimes covered with enamel, particularly in the color blue. In tombs, pottery was used to represent organs of the body removed during embalming, or to create cones, about ten inches tall, engraved with legends of the deceased.

Papyrus

Papyrus is very delicate and was used for writing and painting; it has only survived for long periods when buried in tombs. Every aspect of Egyptian life is found recorded on papyrus, from literary to administrative documents.

Architecture

Architects carefully planned buildings, aligning them with astronomically significant events, such as solstices and equinoxes, and used mainly sun-baked mud brick, limestone, sandstone, and granite. Stone was reserved for tombs and temples, while other buildings, such as palaces and fortresses, were made of bricks. Houses were made of mud from the Nile River that hardened in the sun. Many of these houses were destroyed in flooding or dismantled; examples of preserved structures include the village Deir al-Madinah and the fortress at Buhen.

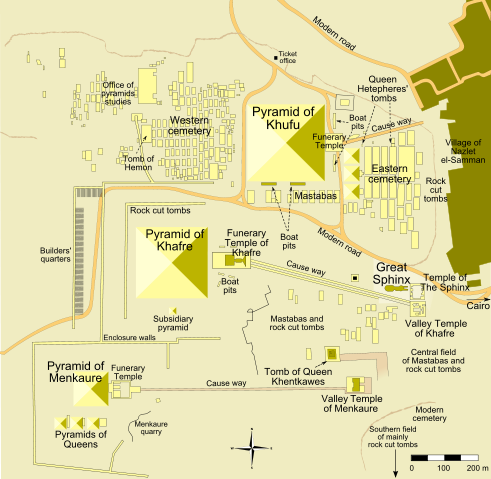

The Giza Necropolis, built in the Fourth Dynasty, includes the Pyramid of Khufu (also known as the Great Pyramid or the Pyramid of Cheops), the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of Menkaure, along with smaller “queen” pyramids and the Great Sphinx.

The Temple of Karnak was first built in the 16th century BCE. About 30 pharaohs contributed to the buildings, creating an extremely large and diverse complex. It includes the Precincts of Amon-Re, Montu and Mut, and the Temple of Amehotep IV (dismantled).

The Luxor Temple was constructed in the 14th century BCE by Amenhotep III in the ancient city of Thebes, now Luxor, with a major expansion by Ramesses II in the 13th century BCE. It includes the 79-foot high First Pylon, friezes, statues, and columns.

The Amarna Period (1353-1336 BCE)

During this period, which represents an interruption in ancient Egyptian art style, subjects were represented more realistically, and scenes included portrayals of affection among the royal family. There was a sense of movement in the images, with overlapping figures and large crowds. The style reflects Akhenaten ‘s move to monotheism, but it disappeared after his death.

Ancient Egyptian Monuments

Ancient Egyptian monuments included pyramids, sphinxes, and temples. These buildings and statues required careful planning and resources, and showed the influence Egyptian religion had on the state and its people.

Learning Objectives

Describe the impressive attributes of the monuments erected by Egyptians in the Old Kingdom

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Ancient Egyptian architects carefully planned buildings, aligning them with astronomically significant events, such as solstices and equinoxes, and used mainly sun-baked mud brick, limestone, sandstone, and granite.

- Egyptian pyramids were highly reflective, referenced the sun, and were usually placed on the West side of the Nile River.

- About 135 pyramids have been discovered in Egypt, with the largest (in Egypt and the world) being the Great Pyramid of Giza.

- The Great Sphinx of Giza is a reclining sphinx (a mythical creature with a lion’s body and a human head); its face is meant to represent the Pharaoh Khafra. It is the world’s oldest and largest monolith.

- Egyptian temples were used for official, formal worship of the gods by the state, and to commemorate pharaohs. The temple was the house of a particular god, and Egyptians would perform rituals, give offerings, re-enact myths, and keep order in the universe (ma’at).

- The Temple of Karnak was first built in the 16th century BCE. About 30 pharaohs contributed to the buildings, creating an extremely large and diverse complex.

- The Luxor Temple was constructed in the 14th century BCE by Amenhotep III in the ancient city of Thebes, now Luxor. It later received a major expansion by Ramesses II in the 13th century BCE.

Key Terms

- solstices: Either of the two times in the year (summer and winter) when the sun reaches its highest or lowest point in the sky at noon.

- equinoxes: Either of the two times in the year when the sun crosses the celestial equator, and day and night are of equal length.

- Hypostyle halls: In ancient Egypt, covered rooms with columns.

- peristyle courts: In ancient Egypt, courts that open to the sky.

- pylon: In ancient Egypt, two tapering towers with a less elevated section between them, forming a gateway.

- friezes: Broad, horizontal bands of sculpted or painted decoration.

- monolith: A large single upright block of stone, especially one shaped into, or serving as, a pillar or monument.

- ma’at: The ancient Egyptian concept of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality and justice.

- obelisks: Stone pillars, typically having a square or rectangular cross section and pyramidal top, used as monuments or landmarks.

Ancient Egyptian architects carefully planned buildings, aligning them with astronomically significant events, such as solstices and equinoxes. They used mainly sun-baked mud brick, limestone, sandstone, and granite. Stone was reserved for tombs and temples, while other buildings, such as palaces and fortresses, were made of bricks.

Pyramids

Egyptian pyramids referenced the rays of the sun, and appeared highly polished and reflective, with a capstone that was generally a hard stone like granite, sometimes plated with gold, silver or electrum. Most were placed west of the Nile, to allow the pharaoh’s soul to join with the sun during its descent.

About 135 pyramids have been discovered in Egypt, with the largest (in Egypt and the world) being the Great Pyramid of Giza. Its base is over 566,000 square feet in area, and was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The Giza Necropolis, built in the Fourth Dynasty, includes the Pyramid of Khufu (also known as the Great Pyramid or the Pyramid of Cheops), the Pyramid of Khafre and the Pyramid of Menkaure, along with smaller “queens” pyramids and the Great Sphinx.

The Great Sphinx of Giza

This limestone statue of a reclining sphinx (a mythical creature with a lion’s body and a human head) is located on the Giza Plateau to the west of the Nile. It is believed the face is meant to represent the Pharaoh Khafra. It is the largest and oldest monolith statue in the world, at 241 feet long, 63 feet wide, and 66.34 feet tall. It is believed to have been built during the reign of Pharaoh Khafra (2558-2532 BCE). It was probably a focus of solar worship, as the lion is a symbol associated with the sun.

Temples

Egyptian temples were used for official, formal worship of the gods by the state, and to commemorate pharaohs. The temple was the house dedicated to a particular god, and Egyptians would perform rituals there, give offerings, re-enact myths and keep order in the universe (ma’at). Pharaohs were in charge of caring for the gods, and they dedicated massive resources to this task. Priests assisted in this effort. The average citizen was not allowed into the inner sanctum of the temple, but might still go there to pray, give offerings, or ask questions of the gods.

The inner sanctuary had a cult image of the temple’s god, as well as a series of surrounding rooms that became large and elaborate over time, evolving into massive stone edifices during the New Kingdom. Temples also often owned surrounding land and employed thousands of people to support its activities, creating a powerful institution. The designs emphasized order, symmetry and monumentality. Hypostyle halls (covered rooms filled with columns) led to peristyle courts (open courts), where the public could meet with priests. At the front of each court was a pylon (broad, flat towers) that held flagpoles. Outside the temple building was the temple enclosure, with a brick wall to symbolically protect from outside disorder; often a sacred lake would be found here. Decoration included reliefs (bas relief and sunken relief) of images and hieroglyphic text and sculpture, including obelisks, figures of gods (sometimes in sphinx form), and votive figures. Egyptian religions faced persecution by Christians, and the last temple was closed in 550 AD.

The Temple of Karnak was first built in the 16th century BCE. About 30 pharaohs contributed to the buildings, creating an extremely large and diverse complex. It includes the Precincts of Amon-Re, Montu and Mut, and the Temple of Amehotep IV (dismantled).

The Luxor Temple was constructed in the 14th century BCE by Amenhotep III in the ancient city of Thebes, now Luxor, with a major expansion by Ramesses II in the 13th century BCE. It includes the 79-foot high First Pylon, friezes, statues, and columns.

Ancient Egyptian Trade

Ancient Egyptians traded with their African and Mediterranean neighbors to obtain goods, such as cedar, lapis lazuli, gold, ivory, and more. They exported goods, such as papyrus, linen, and finished objects using a variety of land and maritime trading routes.

Learning Objectives

Describe the economic structure of ancient Egypt

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Trade was occurring in the 5th century BCE onwards, especially with Canaan, Lebanon, Nubia and Punt.

- Just before the First Dynasty, Egypt had a colony in southern Canaan that produced Egyptian pottery for export to Egypt.

- In the Second Dynasty, Byblos provided quality timber that could not be found in Egypt.

- By the Fifth Dynasty, trade with Punt gave Egyptians gold, aromatic resins, ebony, ivory, and wild animals.

- A well-traveled land route from the Nile to the Red Sea crossed through the Wadi Hammamat. Another route, the Darb el-Arbain, was used from the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt.

- Egyptians built ships as early as 3000 BCE by lashing planks of wood together and stuffing the gaps with reeds. They used them to import goods from Lebanon and Punt.

Key Terms

- myrrh: A fragrant gum resin obtained from certain trees, often used in perfumery, medicine and incense.

- malachite: A bright green mineral consisting of copper hydroxyl carbonate.

- papyrus: A material prepared in ancient Egypt from the stem of a water plant, used in sheets for writing, painting, or making rope, sandals, and boats.

- obsidian: A hard, dark, glasslike volcanic rock.

- electrum: A natural or artifical alloy of gold, with at least 20% silver, used for jewelry.

Early examples of ancient Egyptian trade included contact with Syria in the 5th century BCE, and importation of pottery and construction ideas from Canaan in the 4th century BCE. By this time, shipping was common, and the donkey, camel, and horse were domesticated and used for transportation. Lebanese cedar has been found in the tombs of Nekhen, dated to the Naqada I and II periods. Egyptians during this period also imported obsidian from Ethiopia, gold and incense from Nubia in the south, oil jugs from Palestine, and other goods from the oases of the western desert and the cultures of the eastern Mediterranean. Egyptian artifacts from this era have been found in Canaan and parts of the former Mesopotamia. In the latter half of the 4th century BCE, the gemstone lapis lazuli was being imported from Badakhshan (modern-day Afghanistan).

Just before the First Dynasty, Egypt had a colony in southern Canaan that produced Egyptian pottery for export to Egypt. In the Second Dynasty, Byblos provided quality timber that could not be found in Egypt. By the Fifth Dynasty, trade with Punt gave Egyptians gold, aromatic resins, ebony, ivory, and wild animals. Egypt also traded with Anatolia for tin and copper in order to make bronze. Mediterranean trading partners provided olive oil and other fine goods.

Egypt commonly exported grain, gold, linen, papyrus, and finished goods, such as glass and stone objects.

Land Trade Routes

A well-traveled land route from the Nile to the Red Sea crossed through the Wadi Hammamat, and was known from predynastic times. This route allowed travelers to move from Thebes to the Red Sea port of Elim, and led to the rise of ancient cities.

Another route, the Darb el-Arbain, was used from the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt to trade gold, ivory, spices, wheat, animals, and plants. This route passed through Kharga in the south and Asyut in the north, and was a major route between Nubia and Egypt.

Maritime Trade Routes

Egyptians built ships as early as 3000 BCE by lashing planks of wood together and stuffing the gaps with reeds.

Pharaoh Sahure, of the Fifth Dynasty, is known to have sent ships to Lebanon to import cedar, and to the Land of Punt for myrrh, malachite, and electrum. Queen Hatshepsut sent ships for myrrh in Punt, and extended Egyptian trade into modern-day Somalia and the Mediterranean.

An ancient form of the Suez Canal is believed to have been started by Pharaoh Senusret II or III of the Twelfth Dynasty, in order to connect the Nile River with the Red Sea.

Ancient Egyptian Culture

The Middle Kingdom was a golden age for ancient Egypt, when arts, religion, and literature flourished. Two major innovations of the time were block statues and new forms of literature.

Learning Objectives

Examine the artistic and social developments of the Middle Kingdom

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Middle Kingdom (2134-1690 BCE) was a time of prosperity and stability, as well as a resurgence of art, literature, and architecture.Block statue was a new type of sculpture invented in the Middle Kingdom, and was often used as a funerary monument.

- Literature had new uses during the Middle Kingdom, and many classics were written during the period.

Key Terms

- funerary monuments: Sculpture meant to decorate a tomb within a pyramid.

The Middle Kingdom (2134-1690 BCE) was a time of prosperity and stability, as well as a resurgence of art, literature, and architecture. Two major innovations of the time were the block statue and new forms of literature.

The Block Statue

The block statue came into use during this period. This type of sculpture depicts a squatting man with knees drawn close to the chest and arms folded on top of the knees. The body may be adorned with a cloak, which makes the body appear to be a block shape. The feet may be covered by the cloak, or left uncovered. The head was often carved in great detail, and reflected Egyptian beauty ideals, including large ears and small breasts. The block statue became more popular over the years, with its high point in the Late Period, and was often used as funerary monuments of important, non-royal individuals. They may have been intended as guardians, and were often fully inscribed.

Literature

In the Middle Kingdom period, due to growth of middle class and scribes, literature began to be written to entertain and provide intellectual stimulation. Previously, literature served the purposes of maintaining divine cults, preserving souls in the afterlife, and documenting practical activities. However, some Middle Kingdom literature may have been transcriptions of the oral literature and poetry of the Old Kingdom. Future generations of Egyptians often considered Middle Kingdom literature to be “classic,” with the ultimate example being the Story of Sinuhe.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ancient Egyptian Religion. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Egyptian Religion. Provided by: Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Located at: http://anthropology.msu.edu/anp455-fs12/2012/10/11/egyptian-religion/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Egyptian Social Structure. Provided by: Ancient Civilizations. Located at: http://www.ushistory.org/civ/3b.asp. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 347px-La_Tombe_de_Horemheb_cropped.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:La_Tombe_de_Horemheb_cropped.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Geb_Nut_Shu.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:Geb,_Nut,_Shu.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- BD_Hunefer_cropped_1.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:BD_Hunefer_cropped_1.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Ushabti. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ushabti. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Egyptian Faience. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_faience. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Sunk Relief. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relief#Sunk_relief. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Amarna. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amarna. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Ancient Egyptian Architecture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_architecture. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Art of Ancient Egypt. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_ancient_Egypt. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 347px-La_Tombe_de_Horemheb_cropped.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:La_Tombe_de_Horemheb_cropped.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Geb_Nut_Shu.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:Geb,_Nut,_Shu.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- BD_Hunefer_cropped_1.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:BD_Hunefer_cropped_1.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 326px-Maler_der_Grabkammer_der_Nefertari_004.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_ancient_Egypt#/media/File:Maler_der_Grabkammer_der_Nefertari_004.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-All_Gizah_Pyramids.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_architecture#/media/File:All_Gizah_Pyramids.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 323px-Ka_Statue_of_horawibra.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_ancient_Egypt#/media/File:Ka_Statue_of_horawibra.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 312px-Hypostyle_hall_Karnak_temple.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_architecture#/media/File:Hypostyle_hall,_Karnak_temple.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Pyramid. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyramid. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Great Sphinx of Giza. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Sphinx_of_Giza. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Egyptian Temple. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_temple. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Great Pyramid of Giza. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Pyramid_of_Giza. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 347px-La_Tombe_de_Horemheb_cropped.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:La_Tombe_de_Horemheb_cropped.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Geb_Nut_Shu.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:Geb,_Nut,_Shu.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- BD_Hunefer_cropped_1.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:BD_Hunefer_cropped_1.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 326px-Maler_der_Grabkammer_der_Nefertari_004.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_ancient_Egypt#/media/File:Maler_der_Grabkammer_der_Nefertari_004.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-All_Gizah_Pyramids.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_architecture#/media/File:All_Gizah_Pyramids.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 323px-Ka_Statue_of_horawibra.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_ancient_Egypt#/media/File:Ka_Statue_of_horawibra.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 312px-Hypostyle_hall_Karnak_temple.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_architecture#/media/File:Hypostyle_hall,_Karnak_temple.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 491px-Giza_pyramid_complex_map.svg.png. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Pyramid_of_Giza#/media/File:Giza_pyramid_complex_(map).svg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Karnak-Hypostyle3.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karnak#/media/File:Karnak-Hypostyle3.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Egypt.Giza.Sphinx.02.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Sphinx_of_Giza#/media/File:Egypt.Giza.Sphinx.02.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Pyramide_Djedkare_Isesi_3.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_temple#/media/File:Pyramide_Djedkare_Isesi_3.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Luxor07js.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_temple#/media/File:Luxor07(js).jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Ancient Egyptian Trade. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_trade. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Ancient Egypt. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egypt. License: CC BY: Attribution

- History of Ancient Egypt. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_ancient_Egypt. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 347px-La_Tombe_de_Horemheb_cropped.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:La_Tombe_de_Horemheb_cropped.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Geb_Nut_Shu.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:Geb,_Nut,_Shu.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- BD_Hunefer_cropped_1.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:BD_Hunefer_cropped_1.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 326px-Maler_der_Grabkammer_der_Nefertari_004.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_ancient_Egypt#/media/File:Maler_der_Grabkammer_der_Nefertari_004.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-All_Gizah_Pyramids.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_architecture#/media/File:All_Gizah_Pyramids.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 323px-Ka_Statue_of_horawibra.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_ancient_Egypt#/media/File:Ka_Statue_of_horawibra.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 312px-Hypostyle_hall_Karnak_temple.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_architecture#/media/File:Hypostyle_hall,_Karnak_temple.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 491px-Giza_pyramid_complex_map.svg.png. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Pyramid_of_Giza#/media/File:Giza_pyramid_complex_(map).svg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Karnak-Hypostyle3.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karnak#/media/File:Karnak-Hypostyle3.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Egypt.Giza.Sphinx.02.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Sphinx_of_Giza#/media/File:Egypt.Giza.Sphinx.02.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Pyramide_Djedkare_Isesi_3.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_temple#/media/File:Pyramide_Djedkare_Isesi_3.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Luxor07js.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_temple#/media/File:Luxor07(js).jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Relief_of_Hatshepsut's_expedition_to_the_Land_of_Punt_by_u03a3u03c4u03b1u03c5u0301u03c1u03bfu03c2.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_of_Punt#/media/File:Relief_of_Hatshepsut%27s_expedition_to_the_Land_of_Punt_by_%CE%A3%CF%84%CE%B1%CF%8D%CF%81%CE%BF%CF%82.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Maler_der_Grabkammer_des_Menna_013.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_maritime_history#/media/File:Maler_der_Grabkammer_des_Menna_013.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Hatshepsut.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hatshepsut#/media/File:Hatshepsut.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Block Statue. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_statue. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Ancient Egypt. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egypt#Middle_Kingdom_.282134.E2.80.931690_BC.29. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Middle Kingdom of Egypt. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Kingdom_of_Egypt#Art. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 347px-La_Tombe_de_Horemheb_cropped.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:La_Tombe_de_Horemheb_cropped.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Geb_Nut_Shu.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:Geb,_Nut,_Shu.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- BD_Hunefer_cropped_1.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_religion#/media/File:BD_Hunefer_cropped_1.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 326px-Maler_der_Grabkammer_der_Nefertari_004.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_ancient_Egypt#/media/File:Maler_der_Grabkammer_der_Nefertari_004.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-All_Gizah_Pyramids.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_architecture#/media/File:All_Gizah_Pyramids.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 323px-Ka_Statue_of_horawibra.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_ancient_Egypt#/media/File:Ka_Statue_of_horawibra.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 312px-Hypostyle_hall_Karnak_temple.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_architecture#/media/File:Hypostyle_hall,_Karnak_temple.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 491px-Giza_pyramid_complex_map.svg.png. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Pyramid_of_Giza#/media/File:Giza_pyramid_complex_(map).svg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Karnak-Hypostyle3.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karnak#/media/File:Karnak-Hypostyle3.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Egypt.Giza.Sphinx.02.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Sphinx_of_Giza#/media/File:Egypt.Giza.Sphinx.02.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Pyramide_Djedkare_Isesi_3.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_temple#/media/File:Pyramide_Djedkare_Isesi_3.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Luxor07js.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_temple#/media/File:Luxor07(js).jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Relief_of_Hatshepsut's_expedition_to_the_Land_of_Punt_by_u03a3u03c4u03b1u03c5u0301u03c1u03bfu03c2.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_of_Punt#/media/File:Relief_of_Hatshepsut%27s_expedition_to_the_Land_of_Punt_by_%CE%A3%CF%84%CE%B1%CF%8D%CF%81%CE%BF%CF%82.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Maler_der_Grabkammer_des_Menna_013.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_maritime_history#/media/File:Maler_der_Grabkammer_des_Menna_013.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Hatshepsut.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hatshepsut#/media/File:Hatshepsut.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 286px-Block_statue_Pa-Akh-Ra_CdM.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_statue#/media/File:Block_statue_Pa-Akh-Ra_CdM.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution